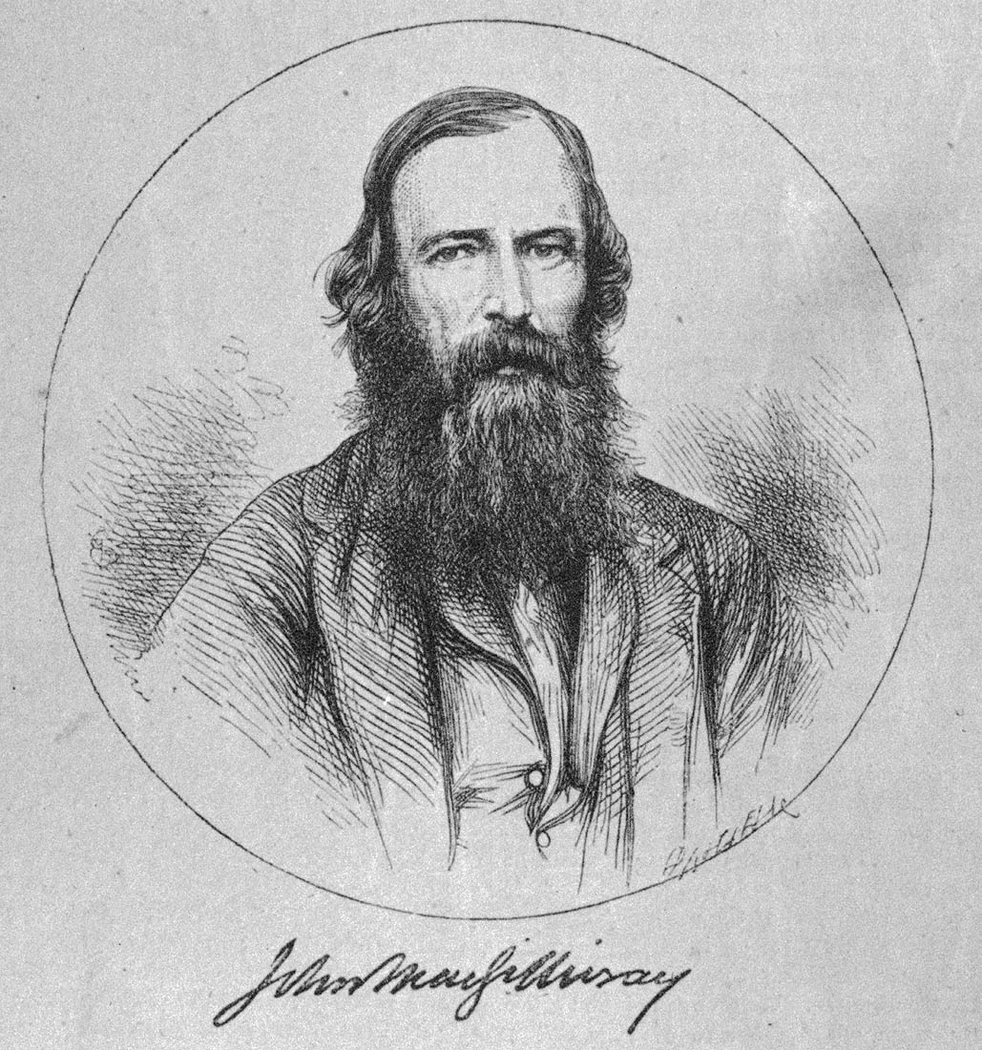

John MacGillivray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John MacGillivray (18 December 1821 – 6 June 1867) was a Scottish naturalist, active in Australia between 1842 and 1867.

MacGillivray was born in

John MacGillivray (18 December 1821 – 6 June 1867) was a Scottish naturalist, active in Australia between 1842 and 1867.

MacGillivray was born in

John MacGillivray (18 December 1821 – 6 June 1867) was a Scottish naturalist, active in Australia between 1842 and 1867.

MacGillivray was born in

John MacGillivray (18 December 1821 – 6 June 1867) was a Scottish naturalist, active in Australia between 1842 and 1867.

MacGillivray was born in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, the son of ornithologist William MacGillivray. He took part in three of the Royal Navy's surveying voyages in the Pacific. In 1842 he sailed as naturalist on board HMS ''Fly'', despatched to survey the Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the Australian mai ...

, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

, and the east coast of Australia, returning to England in 1846.

In the same year he was appointed as naturalist on the voyages of HMS ''Rattlesnake'' (Captain Owen Stanley), collecting in Australian waters at Port Curtis

Port Curtis is a suburb of Rockhampton in the Rockhampton Region, Queensland, Australia. In the , Port Curtis had a population of 281 people.

Geography

The Fitzroy River bounds the suburb to the north-east. Gavial Creek, a tributary of th ...

, Rockingham Bay, Port Molle, Cape York, Gould Island, Lizard Island and Moreton Island in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, Port Essington (Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

) and visiting Sydney (New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

) on several occasions. The expedition was in Hobart, Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, in June 1847 and also surveyed in Bass Strait, and on the southern coast of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

and the Louisiade Archipelago

The Louisiade Archipelago is a string of ten larger volcanic islands frequently fringed by coral reefs, and 90 smaller coral islands in Papua New Guinea.

It is located 200 km southeast of New Guinea, stretching over more than and spread ...

. On this series of voyages his most notable achievement was to make records of the aboriginal languages of the peoples he encountered. His account of the voyages was published in London.

In 1852 he deserted his sick wife and his children in London, and sailed for Australia. T.H. Huxley found his consumptive wife down to her last shilling, and raised £50 to send her and the children back to Australia where her parents could look after her. She died two weeks from Sydney (Desmond 1994 p217).

MacGillivray's journey on HMS ''Herald'' was also doomed to failure. The ship visited Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland P ...

, New South Wales, Dirk Hartog Island

A dirk is a long bladed thrusting dagger.Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), ''Dagger'', The Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. VII, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (1910), p. 729 Historically, it gained its name from the Highland Dirk (Scot ...

and Shark Bay, Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. On this expedition he was accompanied by Scots naturalist William Grant Milne. MacGillivray left the voyage early in 1855, having been dismissed by the captain Henry Mangles Denham

Vice Admiral Sir Henry Mangles Denham (28 August 1800 – 3 July 1887) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station.

Early career

Denham entered the navy in 1809. He served on from 1810 to 1814, initially u ...

. He had become a hopeless drunkard, and when he died, alone in a squalid hotel room, the records noted 'mother and father unknown' (Desmond 1994).

MacGillivray died in Sydney, New South Wales, on 6 June 1867.

He is commemorated in the name of the Fiji petrel ''Pseudobulweria macgillivrayi''.

He also collected a specimen of venomous elapid

Elapidae (, commonly known as elapids ; grc, ἔλλοψ ''éllops'' "sea-fish") is a family of snakes characterized by their permanently erect fangs at the front of the mouth. Most elapids are venomous, with the exception of the genus Emydoce ...

snake on the northeastern coast of Australia. It was described by zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and d ...

Albert Günther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf Günther FRS, also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther (3 October 1830 – 1 February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Günther is ranked the second-most productive re ...

in 1858 as ''Glyphodon tristis'' but it is now called ''Furina tristis

The brown-headed snake (''Furina tristis'') is a small venomous reptile native to the Cape York peninsula in northeastern Australia.

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q3091050

Venomous snakes

Furina

Snakes of Australia

Reptiles described in 185 ...

''. In the late 19th century it was known as MacGillivray's snakeWaite, E.R. 1898 ''A Popular Account of Australian Snakes: with a complete list of the species and an introduction to their habits and organization''. Thomas Shine, Sydney pp. 71. but this name has now fallen into disuse, and it is now called either the brown-headed snake or the grey-naped snake.

See also

*Henry Mangles Denham

Vice Admiral Sir Henry Mangles Denham (28 August 1800 – 3 July 1887) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station.

Early career

Denham entered the navy in 1809. He served on from 1810 to 1814, initially u ...

* William Grant Milne

* European and American voyages of scientific exploration

The era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment. Maritime expeditions in the Age of Discovery were ...

References

* Desmond, Adrian. ''Huxley: the Devil's Disciple''. Joseph, London 1994. * MacGillivray, John. ''Narrative of the voyage of HMS Rattlesnake''. 2 vols, Boone, London 1852. * Orchard A.E. 'A History of Systematic Botany in Australia', in ''Flora of Australia'' Vol 1, 2nd ed, ABRS, 1999.External links

* ** ** * {{DEFAULTSORT:Macgillivray, John 1821 births 1867 deaths Explorers of Australia Scottish botanists 19th-century Scottish people Scottish explorers People from Aberdeen Royal Navy officers Scottish sailors