John Lightfoot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

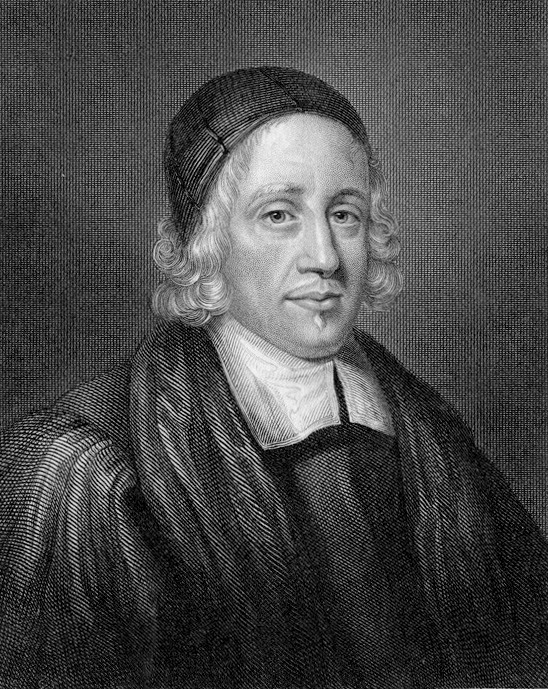

John Lightfoot (29 March 1602 – 6 December 1675) was an

John Lightfoot (29 March 1602 – 6 December 1675) was an

The Whole Works of Rev. John Lightfoot, D.D.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lightfoot, John 1602 births 1675 deaths 17th-century English Anglican priests Westminster Divines Erastians Participants in the Savoy Conference People from Stoke-on-Trent Christian Hebraists Masters of St Catharine's College, Cambridge Vice-Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Clergy from Staffordshire

John Lightfoot (29 March 1602 – 6 December 1675) was an

John Lightfoot (29 March 1602 – 6 December 1675) was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

churchman, rabbinical scholar, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

and Master of St Catharine's College, Cambridge.

Life

He was born in Stoke-on-Trent, the son of Thomas Lightfoot, vicar ofUttoxeter

Uttoxeter ( , ) is a market town in the East Staffordshire district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It is near to the Derbyshire county border. It is situated from Burton upon Trent, from Stafford, from Stoke-on-Trent, from De ...

, Staffordshire. He was educated at Morton Green near Congleton

Congleton is a town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The town is by the River Dane, south of Manchester and north of Stoke on Trent. At the 2011 Census, it had a population of 26,482.

Top ...

, Cheshire, and at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he was regarded as the best orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

among the undergraduates. After taking his degree he became assistant master at Repton School

Repton School is a 13–18 co-educational, independent, day and boarding school in the English public school tradition, in Repton, Derbyshire, England.

Sir John Port of Etwall, on his death in 1557, left funds to create a grammar school whi ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

; after taking orders, he was appointed curate of "Norton-under-Hales" (i.e. Norton in Hales

Norton in Hales is a village and parish in Shropshire, England.

It lies on the A53 between the town of Market Drayton and Woore, Shropshire's most northeasterly village and parish.

Staffordshire is to the east of the parish and Cheshire to the ...

) in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

. There he attracted the notice of Sir Rowland Cotton

Sir Rowland Cotton (baptized 29 January 1581died 22 August 1634) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1605 and 1629.

Cotton was the son of William Cotton, a London draper. He matriculated from St J ...

, an amateur Hebraist

A Hebraist is a specialist in Jewish, Hebrew and Hebraic studies. Specifically, British and German scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries who were involved in the study of Hebrew language and literature were commonly known by this designation, a ...

, who made him his domestic chaplain at Bellaport. Shortly after the removal of Sir Rowland to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Lightfoot, abandoning an intention to go abroad, accepted a charge at Stone, Staffordshire

Stone is a canal town and civil parish in Staffordshire, England, north of Stafford, south of Stoke-on-Trent and north of Rugeley. It was an urban district council and a rural district council before becoming part of the Borough of Staffor ...

, where he continued for about two years. From Stone he removed to Hornsey

Hornsey is a district of north London, England in the London Borough of Haringey. It is an inner-suburban, for the most part residential, area centred north of Charing Cross. It adjoins green spaces Queen's Wood and Alexandra Park to the ...

, near London, for the sake of reading in the library of Sion College

Sion College, in London, is an institution founded by Royal Charter in 1630 as a college, guild of parochial clergy and almshouse, under the 1623 will of Thomas White, vicar of St Dunstan's in the West.

The clergy who benefit by the foundation ...

.

In September 1630 he was presented by Cotton to the rectory of Ashley, Staffordshire

Ashley is a village and former civil parish in the Borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme of Staffordshire, England. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 508. The village is close to the border of Shropshire, adjacent to Loggerheads, and ...

, where he remained until June 1642. He then went to London, probably to supervise the publication of his work, ''A Few and New Observations upon the Book of Genesis: the most of them certain; the rest, probable; all, harmless, strange and rarely heard of before''. Soon after his arrival in London he became minister of St Bartholomew's Church, near the Exchange.

Lightfoot was one of the original members of the Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

; his "Journal of the Proceedings of the Assembly of Divines from January 1, 1643 to December 31, 1644" is a valuable historical source for the brief period to which it relates. He was assiduous in his attendance, and, though frequently standing alone, especially in the Erastian controversy, he exercised considerable influence on the outcome of the discussions of the Assembly.

He was made Master of Catharine Hall (renamed St Catharine's College) by the parliamentary visitors of Cambridge in 1643, and also, on the recommendation of the Assembly, was promoted to the rectory of Much Munden, Hertfordshire; he kept both appointments until his death.

In 1654 Lightfoot had been chosen vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, but continued to live at Munden, in the rectory of which, as well as in the mastership of Catharine Hall, he was confirmed at the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

.

While travelling from Cambridge to Ely, where he had been collated in 1668 by Sir Orlando Bridgeman to a prebendal stall

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

, he caught a severe cold, and died at Ely. Lightfoot bequeathed his library of Old Testament books and documents to Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. It was destroyed in a fire at Harvard in 1764.

Works

His first published work, entitled ''Erubhin'', or ''Miscellanies, Christian and Judaical'', written in his spare time and dedicated to Cotton, appeared in London in 1629. In 1643 Lightfoot published ''A Handful of Gleanings out of the Book of Exodus''. Also in 1643 he was appointed to preach the sermon before theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on occasion of the public fast of 29 March. It was published under the title of ''Elias Redivivus'', the text being ; in it a parallel is drawn between the John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

's ministry and the work of reformation which in the preacher's judgment was incumbent on the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

of his own day.

In 1644 the first instalment of an unfinished work was published in London. The full title was ''The Harmony of the Four Evangelists among themselves, and with the Old Testament, with an explanation of the chiefest difficulties both in Language and Sense: Part I. From the beginning of the Gospels to the Baptism of our Saviour''. The second part, ''From the Baptism of our Saviour to the first Passover after'', followed in 1647, and the third, ''From the first Passover after our Saviour's Baptism to the second'', in 1650. On 26 August 1645 he again preached before the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on the day of their monthly fast. His text was .

In these books he dated Creation to 3929 BC (see Ussher chronology

The Ussher chronology is a 17th-century chronology of the history of the world formulated from a literal reading of the Old Testament by James Ussher, the Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland. The chronology is sometimes associated ...

). Understanding of Lightfoot's precise meaning has been complicated by an 1896 misquotation of him cited by Andrew Dickson White

Andrew Dickson White (November 7, 1832 – November 4, 1918) was an American historian and educator who cofounded Cornell University and served as its first president for nearly two decades. He was known for expanding the scope of college curricu ...

.

Rejecting the doctrine of the millenarian

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenarian ...

sects, Lightfoot had various practical suggestions for the repression of current "blasphemies", for a thorough revision of the Authorized Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

of the Scriptures, for the encouragement of a learned ministry, and for a speedy settlement of the church. ''A Commentary upon the Acts of the Apostles, ironic and critical; the Difficulties of the text explained, and the times of the Story cast into annals. From the beginning of the Book to the end of the Twelfth Chapter. With a brief survey of the contemporary Story of the Jews and Romans (down to the third year of Claudius)'' was published later that year. In 1647 came ''The Harmony, Chronicle, and Order of the Old Testament'', followed in 1655 by ''The Harmony, Chronicle, and Order of the New Testament'', inscribed to Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

.

He helped Brian Walton with the '' Polyglot Bible'' (1657). His own best-known work was the ''Horae Hebraicae et Talmudicae'', in which the volume relating to the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and for ...

appeared in 1658, that relating to the Gospel of Mark in 1663, and those relating to 1 Corinthians, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, and Luke

People

*Luke (given name), a masculine given name (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke (surname) (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luke. Also known as ...

, in 1664, 1671, and 1674 respectively.

The ''Horae Hebraicae et Talmudicae impensae in Acta Apostolorum et in Ep. S. Pauli ad Romanos'' were published posthumously.

Editions

The ''Works of Lightfoot'' were first edited, in 2 vols. fol., by George Bright andJohn Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and lat ...

in 1684.

The ''Opera Omnia, cura Joh. Texelii'', appeared at Rotterdam in 1686 (2 vols. fol.), and again, edited by Johann Leusden

Johannes Leusden (also called Jan (informal), John (English), or Johann (German)) (26 April 1624 – 30 September 1699) was a Dutch Calvinist theologian and orientalist.

Leusden was born in Utrecht. He studied in Utrecht and Amsterdam and ...

, at Franeker in 1699 (3 vols. 101.). A volume of ''Remains'' was published at London in 1700.

The ''Hor. Hebr. et Talm.'' were also edited in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

by Johann Benedict Carpzov (Leipzig, 1675–1679), and again, in English, by Robert Gandell (Oxford, 1859).

The most complete edition is that of the ''Whole Works'', in 13 vols. 8vo. edited, with a life, by John Rogers Pitman

John Rogers Pitman (1782–1861) was an English clergyman and author.

Life

He studied at Christ's Hospital, and then Pembroke College, Cambridge. He was admitted B.A. in 1804, and proceeded M.A. in 1815. Taking holy orders, he was appointed perpe ...

(London, 1822–1825). It includes, besides the works already noticed, numerous sermons, letters and miscellaneous writings; and also ''The Temple, especially as it stood in the Days of our Saviour'' (London, 1650).

References

*External links

The Whole Works of Rev. John Lightfoot, D.D.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lightfoot, John 1602 births 1675 deaths 17th-century English Anglican priests Westminster Divines Erastians Participants in the Savoy Conference People from Stoke-on-Trent Christian Hebraists Masters of St Catharine's College, Cambridge Vice-Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Clergy from Staffordshire