John Gibbon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career

When the Civil War began, Gibbon was serving as a captain of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery at

When the Civil War began, Gibbon was serving as a captain of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery at  Gibbon was promoted to command the 2nd Division, I Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where he was wounded. The wound was minor but was repeatedly infected, so Gibbon was on leave for a few months. Shortly after returning to duty, he learned of the sudden death of his son, John Gibbon, Jr. Gibbon returned for the

Gibbon was promoted to command the 2nd Division, I Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where he was wounded. The wound was minor but was repeatedly infected, so Gibbon was on leave for a few months. Shortly after returning to duty, he learned of the sudden death of his son, John Gibbon, Jr. Gibbon returned for the

Gibbon stayed in the army after the war. He reverted to the

Gibbon stayed in the army after the war. He reverted to the

John Gibbon died in

John Gibbon died in

Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003. . First published 1908 by

''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wright, Steven J., and Blake A. Magner. "John Gibbon: The Man and the Monument." ''Gettysburg Magazine'' 13 (July 1995).

including correspondence, memoirs and commentary on many aspects of his life and the military, are available for research use at the

Photograph

of Gibbon in 1889 with

Photographs

of "loved Commander" Gibbon and his grave. * .

ANC Explorer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gibbon, John 1827 births 1896 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Writers from Philadelphia People from Charlotte, North Carolina Union Army generals People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War People of North Carolina in the American Civil War Iron Brigade United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Nez Perce War

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

officer who fought in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section ofPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, the fourth child of ten born to Dr. John Heysham Gibbons and Catharine Lardner Gibbons. He was the brother of Lardner Gibbon, publisher of ''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon

''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon'' is a two volume publication by two young USN lieutenants William Lewis Herndon (vol. 1) and Lardner A. Gibbon (vol. 2). Gibbon's dates: Aug. 13, 1820 - Jan. 10, 1910. Herndon split the main party in ...

''. When Gibbon was nearly 11 years old the family moved near Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

, after his father took a position as chief assayer at the U.S. Mint. He graduated from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1847 and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery. He served in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

without seeing combat, attempted to keep the peace between Seminoles

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and ...

and settlers in south Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, and taught artillery tactics at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, where he wrote ''The Artillerist's Manual'' in 1859. The manual was a highly scientific treatise on gunnery and was used by both sides in the Civil War. In 1855, Gibbon married Francis "Fannie" North Moale. They had four children: Frances Moale Gibbon, Catharine "Katy" Lardner Gibbon, John Gibbon, Jr. (died a few days after being born) and John S. Gibbon.

Civil War

When the Civil War began, Gibbon was serving as a captain of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery at

When the Civil War began, Gibbon was serving as a captain of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery at Camp Floyd

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. Although his father owned slaves and several of his family members (three brothers, two brothers-in-law and his cousin J. Johnston Pettigrew) served in the Confederate military, Gibbon remained loyal to the Union. Upon arrival in Washington, Gibbon, still in command of the 4th U.S. Artillery, became chief of artillery for Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

. In 1862, he was appointed brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of volunteers and commanded the brigade of westerners known as King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

's Wisconsin Brigade. Gibbon quickly set about drilling his troops and improving their appearance, ordering them to wear white leggings and distinctive, black, 1858 regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

, Hardee hats. Their famous hats earned them the nickname, "The Black Hat Brigade". Soldiers in his brigade despised the white leggings. While still in camp in Washington D.C., Gibbon awoke one morning to find his horse dressed in the leggings. He led the brigade into action against the famous Confederate Stonewall Brigade

The Stonewall Brigade of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, was a famous combat unit in United States military history. It was trained and first led by General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, a professor from Virginia Military ...

at the Battle of Brawner's Farm, a prelude to the Second Battle of Bull Run. He was in command of the brigade during their strong uphill charge at the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

, where Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

exclaimed that the men "fought like iron". From then on, the brigade was known as the "Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought ent ...

". Gibbon led the brigade at the Battle of Antietam, where he was forced to take time away from brigade command to personally man an artillery piece in the bloody fighting at the Cornfield.

Gibbon was promoted to command the 2nd Division, I Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where he was wounded. The wound was minor but was repeatedly infected, so Gibbon was on leave for a few months. Shortly after returning to duty, he learned of the sudden death of his son, John Gibbon, Jr. Gibbon returned for the

Gibbon was promoted to command the 2nd Division, I Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where he was wounded. The wound was minor but was repeatedly infected, so Gibbon was on leave for a few months. Shortly after returning to duty, he learned of the sudden death of his son, John Gibbon, Jr. Gibbon returned for the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

in May 1863, but his division was in reserve and saw little action. At the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

in July, he commanded the 2nd Division, II Corps and temporarily commanded the corps on July 2 and early July 3, 1863, while Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

was elevated to command larger units. At the end of the council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

on the night of July 2, army commander Maj. Gen. George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

took Gibbon aside and predicted, "If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be on your front." Meade's prediction proved correct; Gibbon's division bore the brunt of Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the ...

on July 3, where Gibbon was again wounded. While recovering from his wounds, he commanded a draft depot in Cleveland, Ohio, and attended the dedication of Soldiers' National Cemetery in November 1863 with his close friend and aide Lt. Frank A. Haskell.

Gibbon was back in command of the 2nd Division during Gen. Grant's Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

in May and June 1864, seeing action at the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 186 ...

, and Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S ...

. On June 7, 1864, he was promoted to major general of volunteers. During the subsequent Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

campaign (June 1864 to April 1865), Gibbon became disheartened when his troops refused to fight at Ream's Station in August 1864. He briefly commanded the XVIII Corps before going on sick leave, but his service being too valuable, he returned to command the newly created XXIV Corps in the Army of the James

The Army of the James was a Union Army that was composed of units from the Department of Virginia and North Carolina and served along the James River during the final operations of the American Civil War in Virginia.

History

The Union Department ...

. His troops helped achieve the decisive breakthrough at Third Battle of Petersburg

The Third Battle of Petersburg, also known as the Breakthrough at Petersburg or the Fall of Petersburg, was fought on April 2, 1865, south and southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, at the end of the 292-day Richmond–Petersburg Campaign (sometimes ...

in April 1865, capturing Fort Gregg, part of the Confederate defenses. During the Appomattox Campaign, he helped block the Confederate escape route at the Battle of Appomattox Courthouse

The Battle of Appomattox Court House, fought in Appomattox County, Virginia, on the morning of April 9, 1865, was one of the last battles of the American Civil War (1861–1865). It was the final engagement of Confederate General in Chief, Rober ...

, resulting in Gen. Lee's surrender. He was one of three commissioners for the Confederate surrender.

Indian Wars

Gibbon stayed in the army after the war. He reverted to the

Gibbon stayed in the army after the war. He reverted to the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

and was in command of the 7th Infantry of the Montana Column consisting of the F, G, H, L of the 2nd Cavalry under Jams S. Brisbane from Fort Ellis and of his own regiment of 7th Infantry stationed at Shaw, Baker and Ellis in the Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

...

, during the campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

*Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* Bl ...

against the Sioux in 1876. Gibbon, General George Crook, and General Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to v ...

were to make a coordinated campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

, but Crook was driven back at the Battle of the Rosebud

The Battle of the Rosebud (also known as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Nor ...

, and Gibbon was not close by when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

attacked a very large village on the banks of the Little Bighorn River. The Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

resulted in the deaths of Custer and some 261 of his men. Gibbon's approach on June 26 probably saved the lives of the several hundred men under the command of Major Marcus Reno who were still under siege. Gibbon arrived the next day and helped to bury the dead and evacuate the wounded.

Gibbon was still in command in Montana the following year when he received a telegraph from General Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

to cut off the Nez Percé who had left Idaho, pursued by Howard. (See Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict in 1877 in the Western United States that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the ''Palouse'' tribe led by Red Echo (''Hahtalekin'') and ...

) Gibbon found the Nez Perce near the Big Hole River

The Big Hole River is a tributary of the Jefferson River, approximately long, in Beaverhead County, in southwestern Montana, United States. It is the last habitat in the contiguous United States for native fluvial Arctic grayling and is ...

in western Montana. At the Battle of the Big Hole Gibbon's forces inflicted and suffered heavy casualties, and Gibbon became pinned down by Indian sniper fire. The Nez Perce withdrew in good order after the second day of the battle. In response to Gibbon's urgent call for help, General Howard and an advance party arrived the next day at the battlefield. Gibbon, because of his casualties and a wound he suffered, was unable to continue his pursuit of the Nez Perce.

Gibbon was a Life Member of the Military Service Institution of the United States and won the institution's first gold medal prize for his essay on "Our Indian question", which is published in Volume 2 of the Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States.

Later career and retirement

Gibbon served temporarily as commander of the Department of the Platte in 1884. He was promoted to brigadier general in the regular army in 1885 and took command of the Department of the Columbia, representing all posts in Pacific Northwest. He placedSeattle, Washington

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region ...

, under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

during the anti-Chinese riots of 1886. From 1890, Gibbon was also head of the Military Division of the Atlantic Military Division of the Atlantic, was one of the military divisions of the U. S. Army created by GENERAL ORDERS No. 118. on June 27, 1865 at the end of the American Civil War. President Andrew Johnson directed that the United States was to be divid ...

. Gibbon retired in 1891 upon turning 64.

Gibbon served as president of the Iron Brigade Association, and Commander in Chief of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

from October 1895 until his death the following year. He also gave the commencement address to the West Point Class of 1886.

It is said the Gibbon was travelling through Wisconsin and heard of an Iron Brigade reunion and decided to stop by. Upon knocking on the door of the reunion venue, Gibbon was asked by a veteran who he was. Gibbon is said to have replied, "General Gibbon, and I'm still looking for the bastards who dressed my horse in white leggings!" At this, Gibbon was welcomed inside to take part in the reunion.

Death and legacy

John Gibbon died in

John Gibbon died in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. In addition to his famous and influential ''Artillerist's Manual'' of 1859, he is the author of ''Personal Recollections of the Civil War'' (published posthumously in 1928) and ''Adventures on the Western Frontier'' (also posthumous, 1994) along with many articles in magazines and journals, typically recounting his time in the West and providing his opinions on the government's policy toward Native Americans.

On July 3, 1988, the 125th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, a bronze statue of John Gibbon was dedicated in the Gettysburg National Military Park

The Gettysburg National Military Park protects and interprets the landscape of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Located in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the park is managed by the National Park Service. The GNMP propert ...

, near the site of his wounding in Pickett's Charge.

The town of Gibbon in south central Minnesota is named after him, as are Gibbonsville, Idaho; Gibbon, Oregon; Gibbon, Nebraska

Gibbon is a city in Buffalo County, Nebraska, United States. It is part of the Kearney, Nebraska Micropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 1,833 at the 2010 census.

History

Gibbon was founded in 1871 by a group of settlers consisting o ...

and Gibbon, Washington

Gibbon is an unincorporated community in Benton County, Washington, United States, between Prosser and Benton City.

The community, primarily a railroad junction, was founded as Bender by the Northern Pacific Railway Company in 1884. In April 189 ...

. The Gibbon River and Falls in Yellowstone National Park also bear his name after his 1872 expedition there.

In popular media

*Gibbon was portrayed in the film '' Gettysburg'' by Emile O. Schmidt. *Gibbon was a character in the alternate history novel '' Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War'' (2003) by Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen.Notes

References

* Eicher, John H., andDavid J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Gaff, Alan D. ''On Many a Bloody Field: Four Years in the Iron Brigade''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999. .

* Gibbon, John. ''Adventures on the Western Frontier''. Edited by Alan D. Gaff and Maureen Gaff. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994. .

* Haskell, Frank A.br>''The Battle of Gettysburg: A Soldier's First Account''Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003. . First published 1908 by

MOLLUS

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

, Massachusetts Commandery.

* Herdegen, Lance J. ''The Men Stood Like Iron: How the Iron Brigade Won Its Name''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997. .

* Lavery, Dennis S. "John Gibbon." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. .

* Lavery, Dennis S., and Mark H. Jordan. ''Iron Brigade General: John Gibbon, Rebel in Blue''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. .

* Nolan, Alan T. ''The Iron Brigade, A Military History''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1961. .

* Tagg, Larry''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wright, Steven J., and Blake A. Magner. "John Gibbon: The Man and the Monument." ''Gettysburg Magazine'' 13 (July 1995).

Further reading

* Gibbon, John. ''Gibbon on the Sioux Campaign of 1876''. Bellevue, NV: The Old Army Press, 1970. . * Gibbon, John. ''Personal Recollections of the Civil War''. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1928. . * Nolan, Alan T., and Sharon Eggleston Vipond, eds. ''Giants in their Tall Black Hats: Essays on the Iron Brigade''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998. .External links

* Thincluding correspondence, memoirs and commentary on many aspects of his life and the military, are available for research use at the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a long-established research facility, based in Philadelphia. It is a repository for millions of historic items ranging across rare books, scholarly monographs, family chronicles, maps, press reports and v ...

.

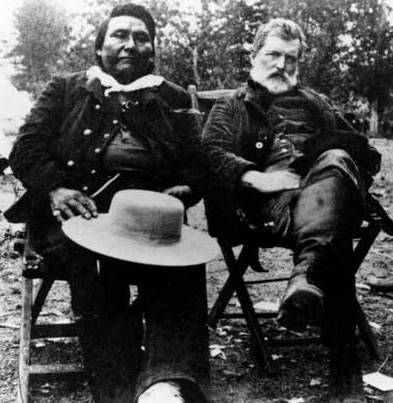

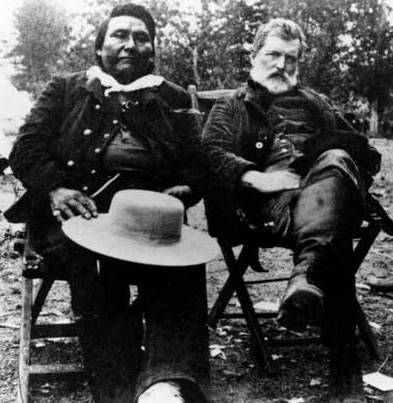

Photograph

of Gibbon in 1889 with

Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

.

Photographs

of "loved Commander" Gibbon and his grave. * .

ANC Explorer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gibbon, John 1827 births 1896 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Writers from Philadelphia People from Charlotte, North Carolina Union Army generals People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War People of North Carolina in the American Civil War Iron Brigade United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Nez Perce War