John Flaxman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British

His father's customers helped him with books, advice, and later with commissions. Particularly significant were the painter George Romney, and a cultivated clergyman, Anthony Stephen Mathew and his wife Mrs. Mathew, in whose house in Rathbone Place the young Flaxman used to meet the best " blue-stocking" society of the day and, among those his own age, the artists

His father's customers helped him with books, advice, and later with commissions. Particularly significant were the painter George Romney, and a cultivated clergyman, Anthony Stephen Mathew and his wife Mrs. Mathew, in whose house in Rathbone Place the young Flaxman used to meet the best " blue-stocking" society of the day and, among those his own age, the artists

By 1780 Flaxman had also begun to earn money by sculpting grave monuments. His early memorials included those to

By 1780 Flaxman had also begun to earn money by sculpting grave monuments. His early memorials included those to

In 1782, aged 27, Flaxman married Anne ("Nancy") Denman, who was to assist him throughout his career. She was well-educated, and a devoted companion. They set up house in

In 1782, aged 27, Flaxman married Anne ("Nancy") Denman, who was to assist him throughout his career. She was well-educated, and a devoted companion. They set up house in

In 1797 he was made an associate of the

In 1797 he was made an associate of the

In the last six years of his life, Flaxman designed decorations for the facades of

In the last six years of his life, Flaxman designed decorations for the facades of  Flaxman died, aged 71, on 7 December 1826. His name is listed as one of the important lost graves on the

Flaxman died, aged 71, on 7 December 1826. His name is listed as one of the important lost graves on the

John Flaxman Collection

, The principal public collections are at University College, in the

Information

from the

World of Dante

– Flaxman's illustrations of Divine Comedy in World of Dante gallery

John Flaxman's Biography, style and artworks

Biography

Flaxman Book Collection

at

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism ...

. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

's pottery. He spent several years in Rome, where he produced his first book illustrations. He was a prolific maker of funerary monuments.

Early life and education

He was born inYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. His father, also named John (1726–1803), was well known as a moulder and seller of plaster cast

A plaster cast is a copy made in plaster of another 3-dimensional form. The original from which the cast is taken may be a sculpture, building, a face, a pregnant belly, a fossil or other remains such as fresh or fossilised footprints – ...

s at the sign of the Golden Head, New Street, Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. His wife's maiden name was Lee, and they had two children, William and John. Within six months of John's birth, the family returned to London. He was a sickly child, high-shouldered, with a head too large for his body. His mother died when he was nine, and his father remarried. He had little schooling and was largely self-educated. He took delight in drawing and modelling from his father's stock-in-trade, and studied translations from classical literature in an effort to understand them.

His father's customers helped him with books, advice, and later with commissions. Particularly significant were the painter George Romney, and a cultivated clergyman, Anthony Stephen Mathew and his wife Mrs. Mathew, in whose house in Rathbone Place the young Flaxman used to meet the best " blue-stocking" society of the day and, among those his own age, the artists

His father's customers helped him with books, advice, and later with commissions. Particularly significant were the painter George Romney, and a cultivated clergyman, Anthony Stephen Mathew and his wife Mrs. Mathew, in whose house in Rathbone Place the young Flaxman used to meet the best " blue-stocking" society of the day and, among those his own age, the artists William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of t ...

and Thomas Stothard

Thomas Stothard (17 August 1755 – 27 April 1834) was an English painter, illustrator and engraver.

His son, Robert T. Stothard was a painter ( fl. 1810): he painted the proclamation outside York Minster of Queen Victoria's accession to the ...

, who became his closest friends. At the age of 12 he won the first prize of the Society of Arts for a medallion, and exhibited in the gallery of the Free Society of Artists; at 15 he won a second prize from the Society of Arts showed at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

for the first time. In the same year, 1770, he entered the academy as a student and won the silver medal. In the competition for the gold medal of the academy in 1772, however, Flaxman was defeated, the prize being awarded by the president, Sir Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

, to a competitor named Engleheart. This episode seemed to help cure Flaxman of a tendency to conceit which led Thomas Wedgwood V

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the ...

to say of him in 1775, "It is but a few years since he was a most supreme coxcomb."

He continued to work diligently, both as a student and as an exhibitor at the academy, with occasional attempts at painting. To the academy he contributed a wax model of Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 time ...

(1770); four portrait models in wax (1771); a terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terra ...

bust, a wax figure of a child, a historical figure (1772); a figure of ''Comedy''; and a relief of a Vestal (1773). During this period he received a commission from a friend of the Mathew family for a statue of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, but he was unable to obtain a regular income from private contracts.

Wedgwood

From 1775 he was employed by the potterJosiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

and his partner Bentley, for whom his father had also done some work, modelling reliefs for use on the company's jasperware

Jasperware, or jasper ware, is a type of pottery first developed by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1770s. Usually described as stoneware, it has an unglazed matte "biscuit" finish and is produced in a number of different colours, of which the most com ...

and basaltware. The usual procedure was to model the reliefs in wax on slate or glass grounds before they cast for production. D'Hancarville's engravings of Sir William Hamilton's collection of ancient Greek vases were an important influence on his work.

His designs included the ''Apotheosis of Homer'' (1778), later used for a vase; ''Hercules in the Garden of Hesperides'' (1785); a large range of small bas-reliefs of which ''The Dancing Hours'' (1776–8) proved especially popular; library busts, portrait medallions, and a chess set.

Early sculptural work

By 1780 Flaxman had also begun to earn money by sculpting grave monuments. His early memorials included those to

By 1780 Flaxman had also begun to earn money by sculpting grave monuments. His early memorials included those to Thomas Chatterton

Thomas Chatterton (20 November 1752 – 24 August 1770) was an English poet whose precocious talents ended in suicide at age 17. He was an influence on Romantic artists of the period such as Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Alth ...

in the church of St Mary Redcliffe

St Mary Redcliffe is an Anglican parish church located in the Redcliffe district of Bristol, England. The church is a short walk from Bristol Temple Meads station. The church building was constructed from the 12th to the 15th centuries, and i ...

in Bristol (1780), Mrs Morley in Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, in Gloucester, England, stands in the north of the city near the River Severn. It originated with the establishment of a minster dedicated to ...

(1784), and the Rev. Thomas and Mrs Margaret Ball in Chichester Cathedral

Chichester Cathedral, formally known as the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Chichester. It is located in Chichester, in West Sussex, England. It was founded as a cathedral in 1075, when the seat of ...

(1785). During the rest of Flaxman's career memorial bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s of this type made up the bulk of his output, and are to be found in many churches throughout England. One example, the monument to George Steevens

George Steevens (10 May 1736 – 22 January 1800) was an English Shakespearean commentator.

Biography Early life

He was born at Poplar, the son of a captain and later director of the East India Company. He was educated at Eton College and ...

, originally in St Matthais Old Church, is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th V ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. His best monumental work was admired for its pathos and simplicity, and for the combination of a truly Greek instinct for rhythmical design and composition with a spirit of domestic tenderness and innocence.

Marriage

In 1782, aged 27, Flaxman married Anne ("Nancy") Denman, who was to assist him throughout his career. She was well-educated, and a devoted companion. They set up house in

In 1782, aged 27, Flaxman married Anne ("Nancy") Denman, who was to assist him throughout his career. She was well-educated, and a devoted companion. They set up house in Wardour Street

Wardour Street () is a street in Soho, City of Westminster, London. It is a one-way street that runs north from Leicester Square, through Chinatown, across Shaftesbury Avenue to Oxford Street. Throughout the 20th century the street became a ...

, and usually spent their summer holidays as guests of the poet William Hayley

William Hayley (9 November 174512 November 1820) was an English writer, best known as the biographer of his friend William Cowper.

Biography

Born at Chichester, he was sent to Eton in 1757, and to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, in 1762; his conne ...

, at Eartham in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

. Flaxman took a shine to the Denman family, particularly Nancy's younger sister Maria, whom he trained as a sculptor, and to whom he left a great deal in his will. He alsio employed Nancy's sister Thomas Denman in his studio and it was Denman who completed the various unfinished sculptures in Flaxman's studio after his death. Flaxman's portrait of Maria is held in the Soane Museum

Sir John Soane's Museum is a house museum, located next to Lincoln's Inn Fields in Holborn, London, which was formerly the home of neo-classical architect, John Soane. It holds many drawings and architectural models of Soane's projects, and ...

.

Italy

In 1787, five years after their marriage, Flaxman and his wife set off forRome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, on a journey partly funded by Wedgwood. His activities in the city included supervising a group of modellers employed by Wedgwood, although he no longer made any work for the potter himself. His sketchbooks show that while there he studied not only Classical, but also Medieval and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

art.Whinney 1971, p. 137.

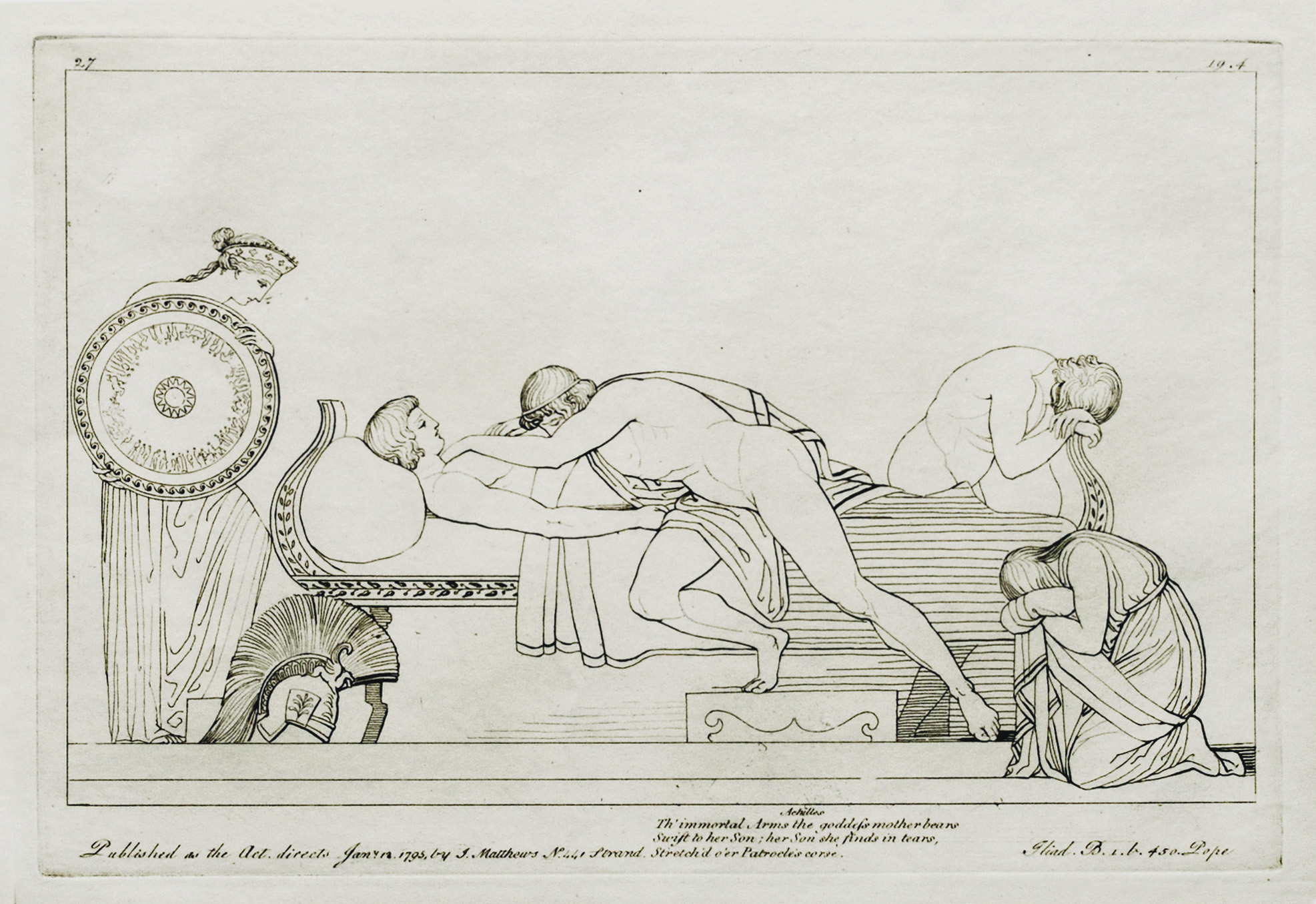

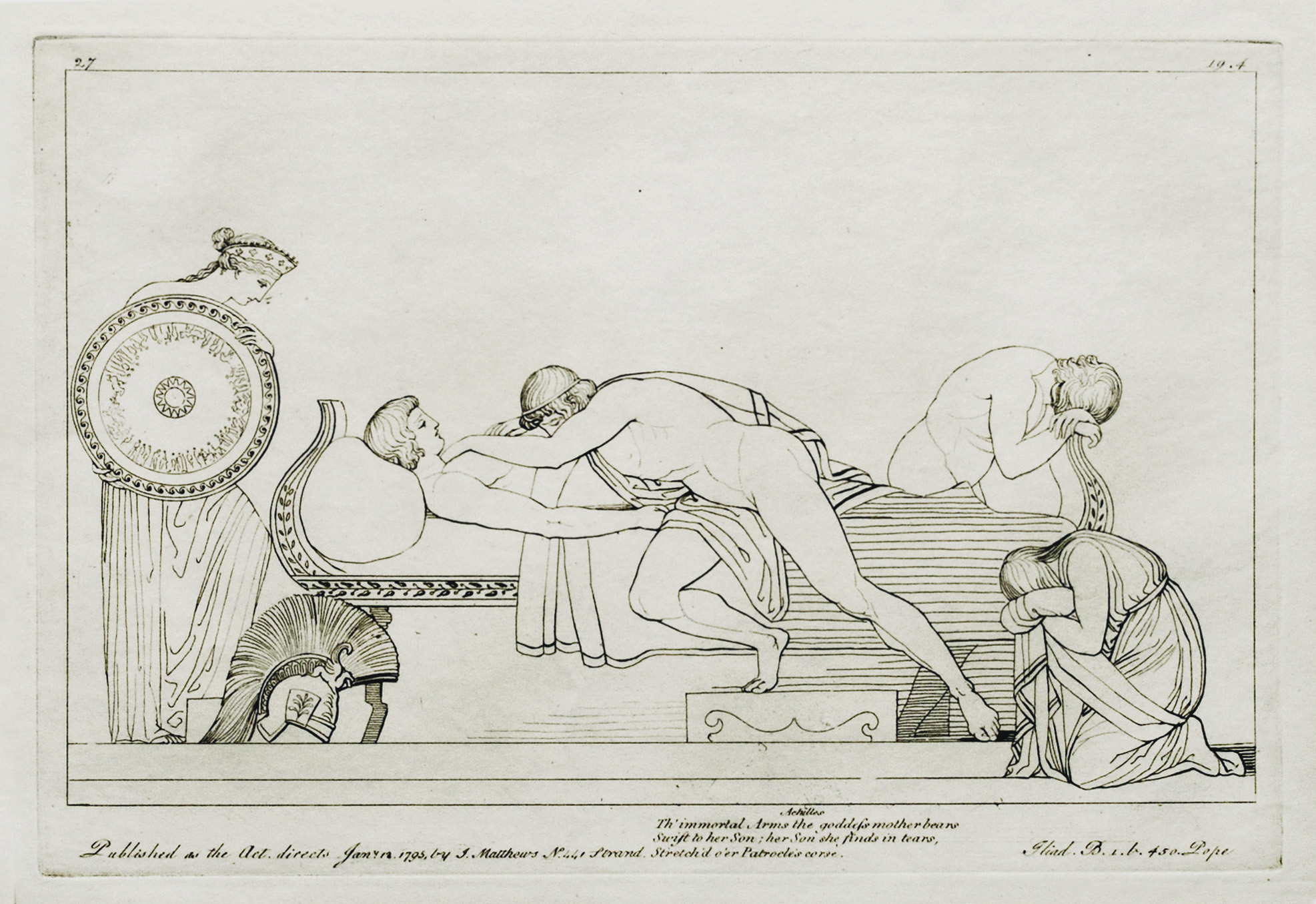

While in Rome he produced the first of the book illustrations for which he was to become famous, and which promoted his influence all over Europe, leading Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

to describe him as "the idol of all dilettanti". His designs for the works of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

(published in 1793) were commissioned by Georgiana Hare-Naylor

Georgiana Hare-Naylor born Georgiana Shipley (circa 1755–1806) was an English painter and art patron.

Life

Georgiana was born at St Asaph in 1752, the fourth daughter of Anna Maria, born Mordaunt, and Jonathan Shipley, then a canon of Christ ...

; those for Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ' ...

(first published in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in 1807) by Thomas Hope; those for Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

by Lady Spencer. All were engraved by Piroli. Flaxman created one hundred and eleven illustrations to Dante's Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

which served as an inspiration for such artists as Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 174616 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings, and e ...

and Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres ( , ; 29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Ingres was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the a ...

, and were used as an academic source for 19th-century art students.

He had originally intended to stay in Italy for little more than two years, but was detained by a commission for a marble group of the ''Fury of Athamas'' for Frederick Hervey, Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry

The Bishop of Derry is an episcopal title which takes its name after the monastic settlement originally founded at Daire Calgach and later known as Daire Colm Cille, Anglicised as Derry. In the Roman Catholic Church it remains a separate title, b ...

, which proved troublesome. By the time of his return to England in the summer of 1794, after an absence of seven years, he had also executed ''Cephalus and Aurora'', a group in marble based on a story in Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his '' magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

''. This was bought by Thomas Hope, who arrived in Rome in 1791, and is often said to have commissioned it. Hope was later to make it the centrepiece of a "Flaxman room" at his London home. It is now in the collection of the Lady Lever Art Gallery

The Lady Lever Art Gallery is a museum founded and built by the industrialist and philanthropist William Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme and opened in 1922. The Lady Lever Art Gallery is set in the garden village of Port Sunlight, on the Wirral ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

.

Return to England

During their homeward journey, the Flaxmans travelled through central and northern Italy. On their return they took a house in Buckingham Street, Fitzroy Square, which they never left. Buckingham Street has since been renamed Greenwell Street, W1; there is a plaque to Flaxman on the front wall of no.7 identifying this as the site of the house where Flaxman lived. Immediately after his return the sculptor published a protest against the scheme (already considered by theFrench Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced b ...

and carried out two years later by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

) to set up a vast central museum of art at Paris to contain works looted from across Europe. Despite this, he later took take advantage of the Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

to go to Paris to see the despoiled treasures collected there.

While still in Rome, Flaxman had sent home models for several sepulchral monuments, including one in relief for the poet William Collins in Chichester cathedral, and one in the round for Lord Mansfield

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, PC, SL (2 March 170520 March 1793) was a British barrister, politician and judge noted for his reform of English law. Born to Scottish nobility, he was educated in Perth, Scotland, before moving to Lond ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

In 1797 he was made an associate of the

In 1797 he was made an associate of the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. He exhibited work at the academy annually, occasionally showing a public monument in the round, like those of Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; french: link=no, Pascal Paoli; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Genoese and later ...

(1798) or Captain Montague (1802) for Westminster Abbey, of Sir William Jones

Sir William Jones (28 September 1746 – 27 April 1794) was a British philologist, a puisne judge on the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal, and a scholar of ancient India. He is particularly known for his proposition of th ...

for University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the unive ...

(1797–1801), of Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

or Howe for St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

, but more often memorials for churches, with symbolic Acts of Mercy or illustrations of biblical texts, usually in low relief. He made a large number of these smaller funerary monuments; his work was in great demand, and he did not charge particularly high prices. Occasionally he would vary his output with a classical piece like those he favoured in his earlier years. Soon after his election as Associate of the academy, he published a scheme for a grandiose monument to be erected on Greenwich Hill, in the form of a figure of Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Grea ...

high, in honour of British naval victories.

Later life

In 1800 he was elected a full Academician, and in 1810 the academy appointed him to the specially created post of Professor of Sculpture. He was a thorough and judicious teacher, and his lectures were often reprinted. According toSidney Colvin

Sir Sidney Colvin (18 June 1845 – 11 May 1927) was a British curator and literary and art critic, part of the illustrious Anglo-Indian Colvin family. He is primarily remembered for his friendship with Robert Louis Stevenson.

Family and early ...

writing in the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' Eleventh Edition: "With many excellent observations, and with one singular merit—that of doing justice, as in those days justice was hardly ever done, to the sculpture of the medieval schools—these lectures lack point and felicity of expression, just as they are reported to have lacked fire in delivery, and are somewhat heavy reading." His most important sculptural works from the years following this appointment were the monument to Mrs Baring in Micheldever church, the richest of all his monuments in relief (1805–1811); that for the Cooke-Yarborough family at Campsall

Campsall is a village in South Yorkshire, England. It lies to the north-west of Doncaster, at an elevation of around 50 feet above sea level. The village contains Campsall Country Park. The village falls within the civil parish of Norton, th ...

church, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, those to Sir Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

for St Paul's (1807); to Captain Webbe for India (1810); to Captains Walker and Beckett for Leeds (1811); to Lord Cornwallis for Prince of Wales's Island (1812); and to Sir John Moore for Glasgow (1813).

He was commissioned to create the monument to Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

(died 1809), by Boulton's son, which is on the north wall of the sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a sa ...

of St. Mary's Church, Handsworth, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, where Boulton is buried. It includes a marble bust of Boulton, set in a circular opening above two putti

A putto (; plural putti ) is a figure in a work of art depicted as a chubby male child, usually naked and sometimes winged. Originally limited to profane passions in symbolism,Dempsey, Charles. ''Inventing the Renaissance Putto''. University o ...

, one holding an engraving of the Soho Manufactory

The Soho Manufactory () was an early factory which pioneered mass production on the assembly line principle, in Soho, Birmingham, England, at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. It operated from 1766–1848 and was demolished in 1853.

B ...

.

Around this time there was much debate over the merits of the sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens, which had been brought to Britain by Lord Elgin, and were hence popularly known as the Elgin marbles

The Elgin Marbles (), also known as the Parthenon Marbles ( el, Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, lit. "sculptures of the Parthenon"), are a collection of Classical Greece, Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of th ...

. When Flaxman first saw them at Elgin's house in 1807, he advised against their restoration.Whinney 1971, p. 140. Flaxman's statements in favour of their purchase by the government to a parliamentary commission carried considerable weight; the sculptures were eventually bought in 1816. His designs for the friezes of ''Ancient Drama'' and ''Modern Drama'', for the facade of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, made in 1809 and carved by John Charles Felix Rossi

John Charles Felix Rossi (8 March 1762 – 21 February 1839), often simply known as Charles Rossi, was an English sculptor.

Life

Early life and education

Rossi was born on 8 March 1762 at Nottingham, where his father Ananso, an Italian from Si ...

, provide an early example of the direct influence of the marbles on British sculpture.

In the years immediately following his Roman period he produced fewer outline designs for publication, except three for William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; 26 November 1731 – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and sce ...

's translations of the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

poems of John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

(1810). In 1817, however, he returned to the genre, publishing a set of designs to Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, which were engraved by Blake. He also designed work for goldsmiths at around this time—a testimonial cup in honour of John Kemble, and the famous and beautiful (though quite un-Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

ic) "Shield of Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's '' Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Pe ...

" designed between 1810 and 1817 for Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. Other late works included a frieze of ''Peace, Liberty and Plenty'', for the Duke of Bedford

Duke of Bedford (named after Bedford, England) is a title that has been created six times (for five distinct people) in the Peerage of England. The first and second creations came in 1414 and 1433 respectively, in favour of Henry IV's third so ...

's sculpture gallery at Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

, and a heroic group of St Michael overthrowing Satan, for Lord Egremont

Earl of Egremont was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1749, along with the subsidiary title Baron of Cockermouth, in Cumberland, for Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset, with remainder to his nephews Sir Charles W ...

's Petworth House

Petworth House in the parish of Petworth, West Sussex, England, is a late 17th-century Grade I listed country house, rebuilt in 1688 by Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, and altered in the 1870s to the design of the architect Anthony Sa ...

, delivered after Flaxman's death.Whinney 1971, p. 144. He also wrote several articles on art and archaeology for Rees's ''Cyclopædia'' (1819–20).

In the last six years of his life, Flaxman designed decorations for the facades of

In the last six years of his life, Flaxman designed decorations for the facades of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

. Some of his drawings for this commission are now held by the Royal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

.

In 1820 Flaxman's wife died. Her younger sister, Maria Denman, and his own sister, Maria Flaxman, continued to live with him, and he continued to work hard. In 1822 he delivered at the academy a lecture in memory of his old friend, Canova

Antonio Canova (; 1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822) was an Italian Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists,. his sculpture was inspired by the Baroque and the cl ...

, who had recently died; in 1823 he received a visit from Schlegel

Schlegel is a German occupational surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Anthony Schlegel (born 1981), former American football linebacker

* August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767–1845), German poet, older brother of Friedrich

* Brad Schlege ...

, who wrote an account of their meeting.

Flaxman died, aged 71, on 7 December 1826. His name is listed as one of the important lost graves on the

Flaxman died, aged 71, on 7 December 1826. His name is listed as one of the important lost graves on the Burdett Coutts Memorial

The Burdett Coutts Memorial Sundial is a structure built in the churchyard of Old St Pancras, London, in 1877–79, at the behest of Baroness Burdett-Coutts. The former churchyard included the burial ground for St Giles-in-the-Fields, where ma ...

in Old St. Pancras Churchyard.

''Flaxman Terrace'' in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest ...

, London, is named after him. The Chelsea telephone exchange that became 020 7352 was also named after him, the digits 352 still corresponding to the old three-letter dialling code FLA.

Studio practice

Most of the carving of his works was carried out by assistants; Margaret Whinney thought that, as a result, "the execution of some of his marbles is a little dull" but that "his plaster models, cast from his own designs in clay, frequently show more sensitive handling". Early in his career, Flaxman made his works in the form of small models which his assistants would scale up when making the finished marble versions. In many cases, notably with the monument to Lord Howe, this proved problematic, and for his later works, he produced full-sized plaster versions for his employees to work from.Critical reception

Flaxman's complicated monuments in the round, such as the three inWestminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

and the four in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

, are considered too "heavy"; but his simple monuments in relief are of finer quality. He thoroughly understood relief, and it gave better scope for his particular talents. His compositions are best studied in the casts from his studio sketches, of which a comprehensive collection is preserved in the Flaxman gallery at University College, London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

.,

University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

.British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, and the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

.

References

Sources

* * This includes a detailed assessment by Colvin of the artist's work.Further reading

* Petherbridge, Deanna, 'Some Thoughts on Flaxman and the Engraved Outlines', Print Quarterly, XXVIII, 2011, pp. 385–91. * - Flaxman was a prominentSwedenborgian

The New Church (or Swedenborgianism) is any of several historically related Christian denominations that developed as a new religious group, influenced by the writings of scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772).

Swedenborgian or ...

.

External links

*Information

from the

National Portrait Gallery (London)

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London housing a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. It was arguably the first national public gallery dedicated to portraits in the world when it ...

World of Dante

– Flaxman's illustrations of Divine Comedy in World of Dante gallery

John Flaxman's Biography, style and artworks

Biography

Flaxman Book Collection

at

University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Flaxman, John

1755 births

1826 deaths

English sculptors

English male sculptors

Royal Academicians

Neoclassical sculptors

English Swedenborgians

Artists from York

British medallists

Burials at St Pancras Old Church

Wedgwood pottery