John Campbell Greenway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

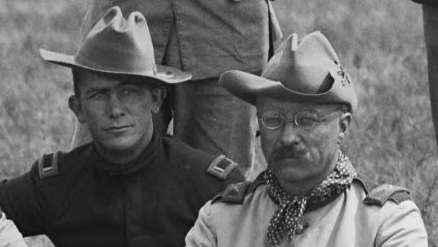

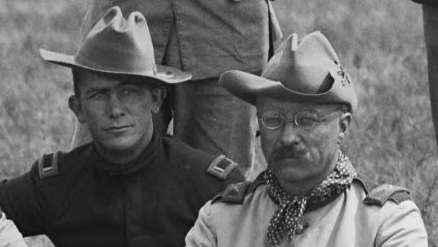

John Campbell Greenway (July 6, 1872 – January 19, 1926) was an American businessman and senior

John Campbell Greenway was born in

John Campbell Greenway was born in

Greenway volunteered for service in 1898 and joined

Greenway volunteered for service in 1898 and joined

He was married to Isabella Munro-Ferguson, who served in the

He was married to Isabella Munro-Ferguson, who served in the

Greenway & Ajo

an article about John Campbell Greenway and Ajo, at the website of the Ajo Copper News. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Greenway, John Campbell 1872 births 1926 deaths 20th-century American businesspeople United States Army personnel of World War I Burials in Kentucky Lauder Greenway Family Recipients of the Legion of Honour Military personnel from Huntsville, Alabama Organization founders Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star Rough Riders United States Army generals United States Army reservists University of Arizona people University of Virginia alumni Yale University alumni Yale Bulldogs football players Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

of the U.S. Army Reserve

The United States Army Reserve (USAR) is a reserve force of the United States Army. Together, the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard constitute the Army element of the reserve components of the United States Armed Forces.

Since July 20 ...

who served with Colonel Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

and commanded infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was the late husband of U.S. congresswoman Isabella Greenway

Isabella Dinsmore Greenway (née Selmes; born March 22, 1886 – December 18, 1953) was an American politician who was the first congresswoman in Arizona history, and as the founder of the Arizona Inn of Tucson. During her life she was also not ...

.

Early life and education

John Campbell Greenway was born in

John Campbell Greenway was born in Huntsville, Alabama

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in t ...

, to Dr. Gilbert C. and Alice White Greenway. On both sides, he was a direct descendant of a line of notable Americans dating to before, and during, the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

including William Campbell, Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, Samuel McDowell, Ephraim McDowell

Ephraim McDowell (November 11, 1771 – June 25, 1830) was an American physician and pioneer surgeon. The first person to successfully remove an ovarian tumor, he has been called "the father of ovariotomy" as well as founding father of abdomina ...

, and Addison White

Addison White (May 1, 1824 – February 4, 1909) was an American politician who served the state of Kentucky in the United States House of Representatives between 1851 and 1853.

Biography

Addison White was born in Abingdon, Washington Coun ...

. He attended Phillips Academy

("Not for Self") la, Finis Origine Pendet ("The End Depends Upon the Beginning") Youth From Every Quarter Knowledge and Goodness

, address = 180 Main Street

, city = Andover

, state = Ma ...

, Andover, attended the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

before completing a PhB in 1895 from the Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffield, ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. He was a member of the Book and Snake

The Society of Book and Snake (incorporated as the Stone Trust Corporation) is the fourth oldest secret society at Yale University and was the first society to induct women into its delegation. Book and Snake was founded at the Sheffield Scientif ...

secret society, president of his class, and a member of noted the Yale Football teams from 1892 to 1895 that went a combined 52–1–2 and were national champions four years in a row. Immediately following graduation, he joined the Carnegie Steel Company

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was forme ...

where he worked briefly before being commissioned in the 1st Volunteer Cavalry of the U.S. Volunteers at the outset of the Spanish–American War.

After being removed from active duty at the end of the Spanish–American War in 1899, Greenway returned to steel and mining and held executive positions in a number of mine, steel, and railroad companies. He supervised development of United States Steel

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in several countries ...

's open pit Canisteo Mine and Trout Lake Washing Plant in Coleraine, Minnesota

Coleraine is a city in Itasca County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 1,970 at the 2010 census. The community was named after Thomas F. Cole, President of the Oliver Iron Mining Company.

U.S. Highway 169 serves as a main route in ...

, one of the first large-scale iron ore benefication plants in the world. Following the successful commissioning of the Trout Lake plant, in 1911 Greenway was recruited by the Calumet and Arizona Mining Company (led by former US Steel

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in several countries ...

executives, the combined entity created by J.P. Morgan which included Carnegie Steel) to develop their newly acquired New Cornelia Mine in Ajo, Arizona

Ajo ( ) is an unincorporated community in Pima County, Arizona, United States. It is the closest community to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The population was 3,304 at the 2010 census. Ajo is located on State Route 85 just from the ...

. He developed the Ajo townsite and developed the New Cornelia into the first large open pit copper mine in Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

. He also served one year as a regent of the University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it was the first university in the Arizona Territory.

T ...

before the United States entered World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Military career

Spanish–American War

Greenway volunteered for service in 1898 and joined

Greenway volunteered for service in 1898 and joined Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

's Rough Riders

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and diso ...

in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. Originally commissioned a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

, he was then promoted to brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

then acting captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the field by Colonel Roosevelt.

Greenway earned a Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

for his courageous service at the Battle of San Juan Hill

The Battle of San Juan Hill, also known as the Battle for the San Juan Heights, was a major battle of the Spanish–American War fought between an American force under the command of William Rufus Shafter and Joseph Wheeler against a Spanish fo ...

. He is referenced on numerous occasions by Roosevelt in his book ''The Rough Riders'' and a book of Greenway's own correspondence was turned into a book entitled ''It Was the Grandest Sight I Ever Saw: Experiences of a Rough Rider As Recorded in the Letters of Lieutenant John Campbell Greenway''. In his book, "The Rough Riders", Roosevelt said about Lieutenant Greenway:

"''A strapping fellow, entirely fearless, modest and quiet, with the ability to take care of the men under him so as to bring them to the highest point of soldierly perfection, to be counted upon with absolute certainty in every emergency; not only doing his duty, but always on the watch to find some new duty which he could construe to be his, ready to respond with eagerness to the slightest suggestion of doing something, whether it was dangerous or merely difficult and laborious''."

World War I

Greenway was returned to active service as alieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

at the dawn of America entering World War I. Originally based at Toul Sector, he partook in the Battle of Cantigny

The Battle of Cantigny, fought May 28, 1918 was the first major American battle and offensive of World War I. The U.S. 1st Division, the most experienced of the five American divisions then in France and in reserve for the French Army near the v ...

, the first large-scale counterattack on German lines by the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought alon ...

(AEF) with the 1st Battalion of the 26th Infantry, 1st Division, commanded by Major Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Theodore Roosevelt III ( ), often known as Theodore Jr.Morris, Edmund (1979). ''The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt''. index.While it was President Theodore Roosevelt who was legally named Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the President's fame made it simple ...

, the son of his commander during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. During the war, Greenway would fight in numerous battles including Battle of Saint-Mihiel

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a major World War I battle fought from 12–15 September 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and 110,000 French troops under the command of General John J. Pershing of the United States against ...

and the Battle of Château-Thierry. He was especially praised for his heroic conduct in battle and was cited for bravery at Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

, the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, and the Ordre de l'Étoile Noire

The Order of the Black Star (''Ordre de l'Étoile Noire'') was an order of knighthood established on 1 December 1889 at Porto-Novo by Toffa, future king of Dahomey (today the Republic of Benin). Approved and recognised by the French government o ...

for commanding the 101st Infantry, 26th Division, during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He also received a Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

and the World War I Victory Medal.

In late 1918, Colonel Greenway was severely gassed by German forces and honorably discharged from active service by the Army, though he remained active in the U.S. Army Reserve. He arrived back in Arizona in early 1919 to resume his role in the mining industries there.

Aftermath

In 1919 Greenway was promoted to the rank ofcolonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of the infantry, and three years later he was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

. His post-war military career included work with Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Theodore Roosevelt III ( ), often known as Theodore Jr.Morris, Edmund (1979). ''The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt''. index.While it was President Theodore Roosevelt who was legally named Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the President's fame made it simple ...

for the Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serves ...

, the oldest branch of America's United States Intelligence Community

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

.

Personal life

He was married to Isabella Munro-Ferguson, who served in the

He was married to Isabella Munro-Ferguson, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

as a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

from 1933 to 1937 and was the first congresswoman from Arizona. They had one child, Jack. Greenway's brother, James C. Sr., married Harriet Lauder Greenway of the Lauder Greenway Family. His nephews include renowned ornithologist and Naval Intelligence Officer James Cowan Greenway and arts patron G. Lauder Greenway, longtime chairman of the Metropolitan Opera Guild

The Metropolitan Opera Guild was established in 1935 to broaden the base of support for the Metropolitan Opera, promote greater interest in opera, and develop future audiences by reaching out to a wide public and serving as an educational resource ...

, New York.

Legacy

In 1930 Arizona placedGutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Mountain in Georg ...

's statue of Greenway in the U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

's National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old ...

.Murdock, Myrtle Chaney, ''National Statuary Hall in the Nation's Capitol'', Monumental Press, Inc., Washington, D.C., 1955 pp. 88–89 The statue remained there until being replaced in 2015 by one of Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for presiden ...

; the Greenway statue was moved to the Polly Rosenbaum Archives and History Building near the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix. There is another casting of the Borglum statue in Tucson

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

.

A Charles Henry Niehaus

Charles Henry Niehaus (January 24, 1855 — June 19, 1935), was an American sculptor.

Education

Niehaus was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to German parents. He began working as a marble and wood carver, and then gained entrance to the McMicken ...

statue of Greenway's great great grandfather, Dr. Ephraim McDowell

Ephraim McDowell (November 11, 1771 – June 25, 1830) was an American physician and pioneer surgeon. The first person to successfully remove an ovarian tumor, he has been called "the father of ovariotomy" as well as founding father of abdomina ...

, was placed in the National Statuary Hall in 1929 by Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, making them the only direct relatives to have shared the honor.

Greenway Road in Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ; nv, Hoozdo; es, Fénix or , yuf-x-wal, Banyà:nyuwá) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities and towns in Arizona#List of cities and towns, most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona, with 1 ...

, Greenway High School

Greenway High School is a public secondary school located in Phoenix, Arizona. It is a part of the Glendale Union High School District. It was named after John Campbell Greenway, a mining engineer and United States Senator.

In the 1994–95 and ...

in Phoenix, Greenway Public Schools in Coleraine, Minnesota

Coleraine is a city in Itasca County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 1,970 at the 2010 census. The community was named after Thomas F. Cole, President of the Oliver Iron Mining Company.

U.S. Highway 169 serves as a main route in ...

, and Greenway Township, Itasca County, Minnesota are named in his honor.

See also

*List of members of the American Legion

This table provides a list of notable members of The American Legion.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

References

External links

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:American Legion, List O ...

* List of people from Alabama

This is a listing of notable people born in, or notable for their association with the U.S. state of Alabama.

__NOTOC__

A

* Hank Aaron, Hall of Fame Major League Baseball player ( Mobile)

* Ralph Abernathy, civil rights leader, Baptis ...

* List of Yale University people

Yalies are persons affiliated with Yale University, commonly including alumni, current and former faculty members, students, and others. Here follows a list of notable Yalies.

Alumni

For a list of notable alumni of Yale Law School, see List ...

References

Other sources

*Boice, Donald (1975) ''John C. Greenway and the Opening of the Western Mesabi'' (Itasca Community College Foundation)External links

Greenway & Ajo

an article about John Campbell Greenway and Ajo, at the website of the Ajo Copper News. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Greenway, John Campbell 1872 births 1926 deaths 20th-century American businesspeople United States Army personnel of World War I Burials in Kentucky Lauder Greenway Family Recipients of the Legion of Honour Military personnel from Huntsville, Alabama Organization founders Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star Rough Riders United States Army generals United States Army reservists University of Arizona people University of Virginia alumni Yale University alumni Yale Bulldogs football players Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni