John B. Anderson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

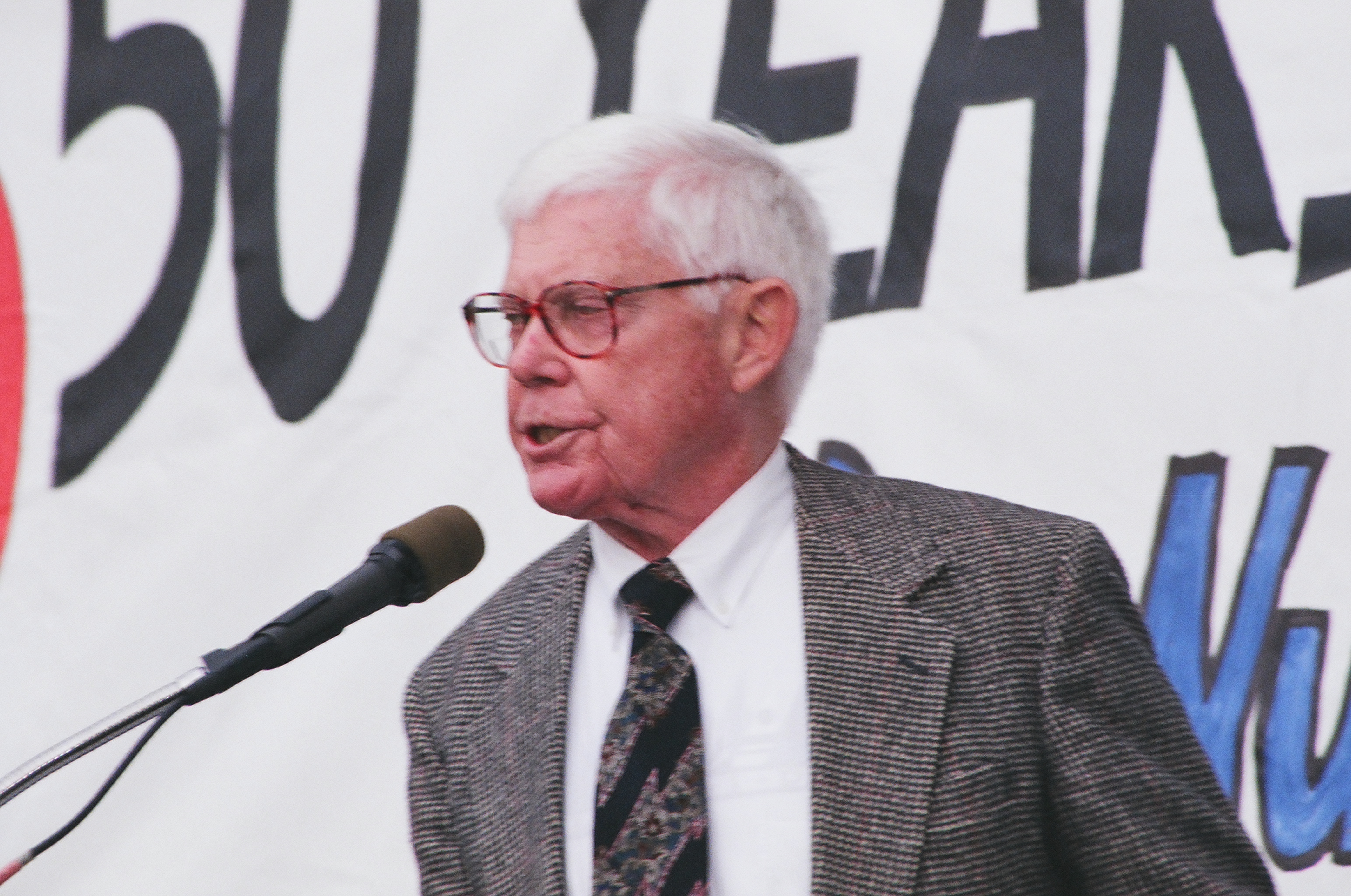

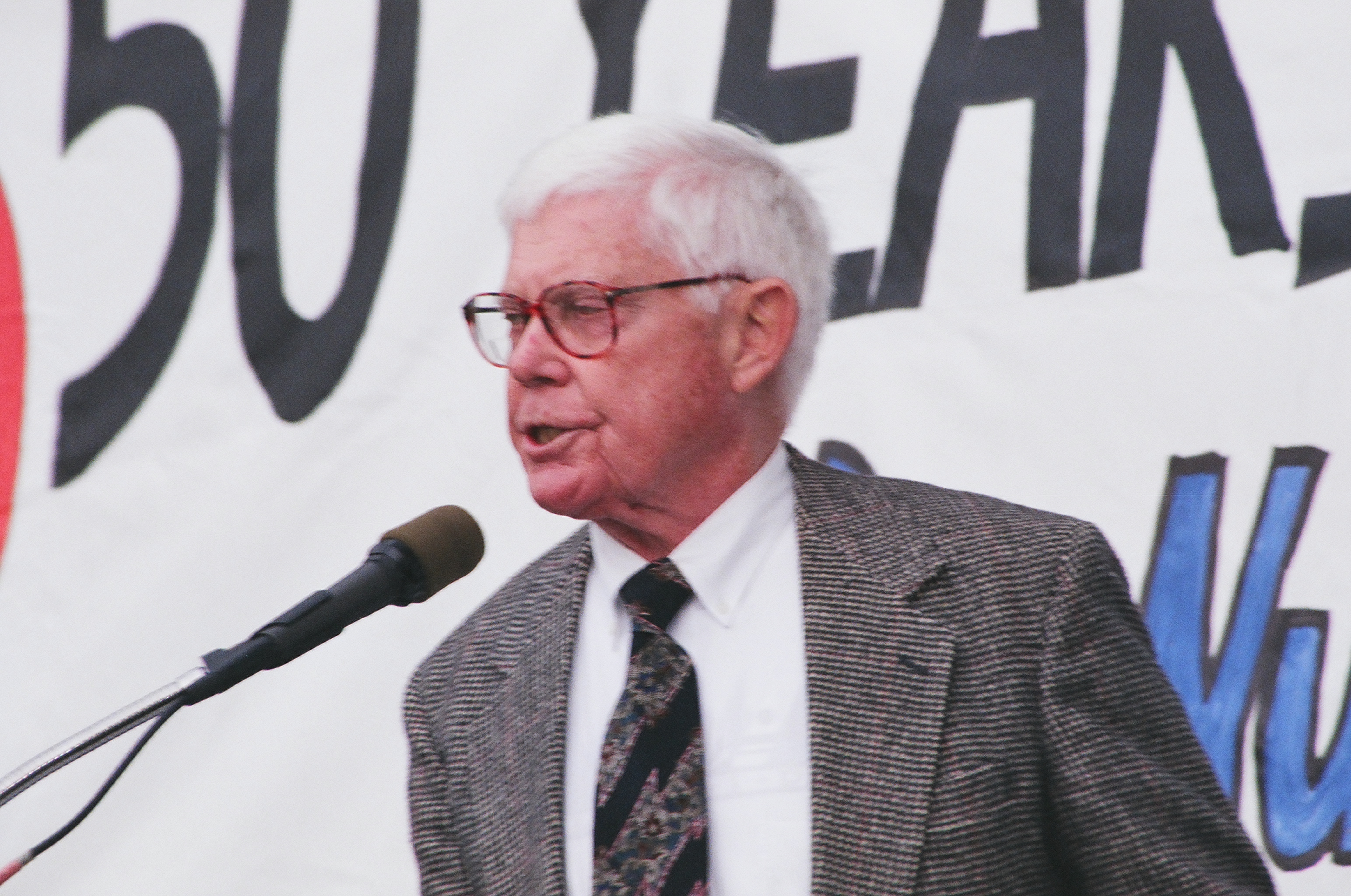

John Bayard Anderson (February 15, 1922 – December 3, 2017) was an American lawyer and politician who served in the

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected State's Attorney in

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected State's Attorney in

In 1978, Anderson formed a presidential campaign

In 1978, Anderson formed a presidential campaign

On January 5, 1980, in the Republican candidates' debate in

On January 5, 1980, in the Republican candidates' debate in

The Republican platform failed to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment or support extension of time for its ratification. Anderson was a strong supporter of both. Pollsters were finding that Anderson was much more popular across the country with all voters than he was in the Republican primary states. Without any campaigning, he was running at 22% nationally in a three-way race. Anderson's personal aide and confidant, Tom Wartowski, encouraged him to remain in the Republican Party. Anderson faced a huge number of obstacles as a non-major party candidate: having to qualify for 51 ballots (which the major parties appeared on automatically), having to raise money to run a campaign (the major parties received close to $30 million in government money for their campaigns), having to win national coverage, having to build a campaign overnight, and having to find a suitable running mate among them. He built a new campaign team, qualified for every ballot, raised a great deal of money, and rose in the polls to as high as 26% in one

The Republican platform failed to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment or support extension of time for its ratification. Anderson was a strong supporter of both. Pollsters were finding that Anderson was much more popular across the country with all voters than he was in the Republican primary states. Without any campaigning, he was running at 22% nationally in a three-way race. Anderson's personal aide and confidant, Tom Wartowski, encouraged him to remain in the Republican Party. Anderson faced a huge number of obstacles as a non-major party candidate: having to qualify for 51 ballots (which the major parties appeared on automatically), having to raise money to run a campaign (the major parties received close to $30 million in government money for their campaigns), having to win national coverage, having to build a campaign overnight, and having to find a suitable running mate among them. He built a new campaign team, qualified for every ballot, raised a great deal of money, and rose in the polls to as high as 26% in one

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students. He capitalized on that by becoming a visiting professor at a series of universities: Stanford University,

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students. He capitalized on that by becoming a visiting professor at a series of universities: Stanford University,

Arlington National Cemetery

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Anderson, John B. 1922 births 2017 deaths 20th-century American politicians United States Army personnel of World War II American people of Swedish descent Centrism in the United States Harvard Law School alumni Brandeis University faculty Burials at Arlington National Cemetery District attorneys in Illinois Duke University faculty Illinois Independents Members of the Evangelical Free Church of America Military personnel from Illinois Oregon State University faculty Politicians from Rockford, Illinois Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois United States Army non-commissioned officers Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election University of Illinois College of Law alumni University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, representing Illinois's 16th congressional district

The 16th congressional district of Illinois is represented by Republican Darin LaHood.

Geographic boundaries 2011 redistricting

The congressional district covers parts of DeKalb, Ford, Stark, Will and Winnebago counties, and all of Boone, Bu ...

from 1961 to 1981. A member of the Republican Party, he also served as the Chair of the House Republican Conference

The House Republican Conference is the party caucus for Republicans in the United States House of Representatives. It hosts meetings and is the primary forum for communicating the party's message to members. The Conference produces a daily pu ...

from 1969 until 1979. In 1980, he ran an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

campaign for president, receiving 6.6% of the popular vote.

Born in Rockford, Illinois, Anderson practiced law after serving in the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. After a stint in the United States Foreign Service

The United States Foreign Service is the primary personnel system used by the diplomatic service of the United States federal government, under the aegis of the United States Department of State. It consists of over 13,000 professionals carry ...

, he won election as the State's Attorney for Winnebago County, Illinois

Winnebago County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 285,350 making it the seventh most populous county in Illinois behind Cook County and its five surrounding collar counties. ...

. He won election to the House of Representatives in 1960 in a strongly Republican district. Initially one of the most conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

members of the House, Anderson's views moderated during the 1960s, particularly regarding social issues. He became Chairman of the House Republican Conference

The House Republican Conference is the party caucus for Republicans in the United States House of Representatives. It hosts meetings and is the primary forum for communicating the party's message to members. The Conference produces a daily pu ...

in 1969 and remained in that position until 1979. He strongly criticized the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

as well as President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's actions during the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

. Anderson entered the 1980 Republican presidential primaries, introducing his signature campaign proposal of raising the gas tax

A fuel tax (also known as a petrol, gasoline or gas tax, or as a fuel duty) is an excise tax imposed on the sale of fuel. In most countries the fuel tax is imposed on fuels which are intended for transportation. Fuels used to power agricultural v ...

while cutting social security taxes.

He established himself as a contender for the nomination in the early primaries, but eventually dropped out of the Republican race, choosing to pursue an independent campaign for president. In the election, he finished third behind Republican nominee Ronald Reagan and Democratic President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

. He won support among Democrats who became disillusioned with Carter, as well as Rockefeller Republican

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to- liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vice President of ...

s, independents, liberal intellectuals, and college students. After the election, he resumed his legal career and helped found FairVote

FairVote, formerly the Center for Voting and Democracy, is a 501(c)(3) organization that advocates electoral reform in the United States.

Founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional r ...

, an organization that advocates for electoral reform

Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems which alters how public desires are expressed in election results. That can include reforms of:

* Voting systems, such as proportional representation, a two-round system (runoff voting), instant-r ...

, including an instant-runoff voting system. He also won a lawsuit against the state of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, ''Anderson v. Celebrezze

''Anderson v. Celebrezze'', 460 U.S. 780 (1983), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Ohio's filing deadline for independent candidates was unconstitutional.

Background

John B. Anderson was a declared candidate f ...

'', in which the Supreme Court struck down early filing deadlines for independent candidates. Anderson served as a visiting professor at numerous universities and was on the boards of several organizations. He endorsed Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the U ...

in 2000 and helped found the Justice Party in 2012.

Early life and career

Anderson was born in Rockford, Illinois, where he grew up, the son of Mabel Edna (née Ring) and E. Albin Anderson. His father was a Swedish immigrant, as were his maternal grandparents. In his youth, he worked in his family's grocery store. He graduated as the valedictorian of his class (1939) atRockford Central High School

Rockford High School (sometimes referred to as Rockford Central High School) was the first school opened by the newly formed, citywide, school district, Rockford Public School District 205 in Rockford, Illinois. Opened in 1885, it served as a hig ...

. He graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the Univer ...

in 1942, and started law school, but his education was interrupted by World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. He enlisted in the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

in 1943, and served as a staff sergeant in the U.S. Field Artillery in France and Germany until the end of the war, receiving four service star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or se ...

s. After the war, Anderson returned to complete his education, earning a Juris Doctor (J.D.) from the University of Illinois College of Law

The University of Illinois College of Law (Illinois Law or UIUC Law) is the law school of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a public university in Champaign, Illinois. It was established in 1897 and offers the J.D., LL.M., and J.S ...

in 1946.

Anderson was admitted to the Illinois bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

the same year, and practiced law in Rockford. Soon after, he moved east to attend Harvard Law School, obtaining a Master of Laws

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is an advanced postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in a related subject. In mos ...

(LL.M.) in 1949. While at Harvard, he served on the faculty of Northeastern University School of Law

Northeastern University School of Law (NUSL) is the law school of Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded as an evening program to meet the needs of its local community, NUSL is nationally recognized for its cooperative legal ...

in Boston. In another brief return to Rockford, Anderson practiced at the law firm Large, Reno & Zahm (now Reno & Zahm LLP). Thereafter, Anderson joined the Foreign Service

Diplomatic service is the body of diplomats and foreign policy officers maintained by the government of a country to communicate with the governments of other countries. Diplomatic personnel obtains diplomatic immunity when they are accredited to o ...

. From 1952 to 1955, he served in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, as the Economic Reporting Officer in the Eastern Affairs Division, as an adviser on the staff of the United States High Commissioner for Germany. At the end of his tour, he left the foreign service and once again returned to the practice of law in Rockford.

Early political career

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected State's Attorney in

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected State's Attorney in Winnebago County, Illinois

Winnebago County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 285,350 making it the seventh most populous county in Illinois behind Cook County and its five surrounding collar counties. ...

, first winning a four-person race in the April primary by 1,330 votes and then the general election in November by 11,456 votes. After serving for one term, he was ready to leave that office when the local congressman, 28-year incumbent Leo E. Allen, announced his retirement. Anderson joined the Republican primary for Allen's 16th District seat—the real contest in this then-solidly Republican district based in Rockford and stretching across the state’s northwest corner. He won a five-way primary in April (by 5,900 votes) in April and then the general election in November (by 45,000 votes). He served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

for ten terms, from 1961 to 1981.

Initially, Anderson was among the most conservative members of the Republican caucus. Three times (in 1961, 1963, and 1965) in his early terms as a Congressman, Anderson introduced a constitutional amendment to attempt to "recognize the law and authority of Jesus Christ" over the United States. The bills died quietly, but later came back to haunt Anderson in his presidential candidacy. Anderson voted in favor of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 1968

The year was highlighted by protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – " Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

* Janu ...

, as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

As he continued to serve, the atmosphere of the 1960s weighed on Anderson and he began to re-think some of his beliefs. By the late 1960s, Anderson's positions on social issues shifted to the left, though his fiscal philosophy remained largely conservative. At the same time, he was held in high esteem by his colleagues in the House. In 1964, he won appointment to a seat on the powerful Rules Committee. In 1969, he became Chairman of the House Republican Conference

The House Republican Conference is the party caucus for Republicans in the United States House of Representatives. It hosts meetings and is the primary forum for communicating the party's message to members. The Conference produces a daily pu ...

, the number three position in the House Republican hierarchy in what was (at that time) the minority party. Anderson increasingly found himself at odds with conservatives in his home district and other members of the House. He was not always a faithful supporter of the Republican agenda, despite his high rank in the Republican caucus. He was very critical of the Vietnam War, and was a very controversial critic of Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

during Watergate. In 1974, despite his criticism of Nixon, the strong anti-Republican tide in that year's election held him to 55 percent of the vote, what would be the lowest percentage of his career.

His spot as the chairman of the House Republican Committee was challenged three times after his election and, when Gerald Ford was defeated in the 1976 Presidential campaign, Anderson lost a key ally in Washington. In 1970 and 1972, Anderson had a Democratic challenger in Rockford Professor John E. Devine. In both years, Anderson defeated Devine by a wide margin. In late 1977, a fundamentalist television minister from Rockford, Don Lyon, announced that he would challenge Anderson in the Republican primary. It was a contentious campaign, where Lyon, with his experience before the camera, proved to be a formidable candidate.Ira Teinowitz, "Anderson–Lyon Race is Top Attraction", ''Rockford Morning Star'', February 26, 1978. Lyon raised a great deal of money, won backing from many conservatives in the community and party, and put quite a scare into the Anderson team. Though Anderson was a leader in the House and the campaign commanded national attention, Anderson won the primary by 16% of the vote. Anderson was aided in this campaign by strong newspaper endorsements and crossover support from independents and Democrats.

1980 presidential campaign

Early campaign

In 1978, Anderson formed a presidential campaign

In 1978, Anderson formed a presidential campaign exploratory committee

In the election politics of the United States, an exploratory committee is an organization established to help determine whether a potential candidate should run for an elected office. They are most often cited in reference to candidates for pre ...

, finding little public or media interest. In late April 1979, Anderson made the decision to enter the Republican primary, joining a field that included Ronald Reagan, Bob Dole, John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician. He served as the 39th governor of Texas and as the 61st United States secretary of the Treasury. He began his career as a Democrat and later became a Republic ...

, Howard Baker, George H. W. Bush, and the perennial candidate

A perennial candidate is a political candidate who frequently runs for elected office and rarely, if ever, wins. Perennial candidates' existence lies in the fact that in some countries, there are no laws that limit a number of times a person can ...

Harold Stassen

Harold Edward Stassen (April 13, 1907 – March 4, 2001) was an American politician who was the 25th Governor of Minnesota. He was a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in 1948, considered for a ti ...

. Within the last weeks of 1979, Anderson introduced his signature campaign proposal, advocating that a 50-cent a gallon gas tax

A fuel tax (also known as a petrol, gasoline or gas tax, or as a fuel duty) is an excise tax imposed on the sale of fuel. In most countries the fuel tax is imposed on fuels which are intended for transportation. Fuels used to power agricultural v ...

be enacted with a corresponding 50% reduction in social security taxes. Anderson built state campaigns in four targeted states—New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

, and Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. He won some political support among Republicans, picking up endorsements along the way that helped legitimize him in the race. He began to build support among media elites, who appreciated his articulateness, straightforward manner, moderate positions, and his refusal to walk down the conservative path that all of the other Republicans were traveling.

He often referred to his candidacy as "a campaign of ideas." He supported tax credits for businesses' research-and-development budgets, which he believed would increase American productivity; he also supported increasing funding for research at universities. He supported conservation and environmental protection. He opposed Ronald Reagan's proposal to cut taxes broadly, which he feared would increase the national debt and the inflation rate (which was very high at the time of the campaign). He also supported a tax on gasoline to reduce dependence on foreign oil. He supported the Equal Rights Amendment, gay rights and abortion rights

Abortion-rights movements, also referred to as pro-choice movements, advocate for the right to have legal access to induced abortion services including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their pre ...

generally; he also touted his perfect record of having supported all civil rights legislation since 1960. He opposed the requirement for registration for the military draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

, which Jimmy Carter had reinstated. This made him appealing to many liberal college students who were dissatisfied with Carter. However, he also voiced support for a strong, flexible military and support for NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

against USSR, as well as several other positions associated with Republicans, including deregulation of some industries such as natural gas and oil prices, and a balanced budget to be achieved mainly by reductions in government spending.

Republican primary

On January 5, 1980, in the Republican candidates' debate in

On January 5, 1980, in the Republican candidates' debate in Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines () is the capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is also the county seat of Polk County. A small part of the city extends into Warren County. It was incorporated on September 22, 1851, as Fort Des Moines, ...

, unlike the other candidates, Anderson said lowering taxes, increasing defense spending, and balancing the budget were an impossible combination. In a stirring summation, Anderson invoked his father's immigration to the United States and said that Americans would have to make sacrifices "for a better tomorrow." For the next week, Anderson's name and face were all over the national news programs, in newspapers, and in national news magazines. Anderson spent less than $2000 in Iowa, but he finished with 4.3% of the vote. The television networks were covering the event, portraying Anderson to a national audience as a man of character and principle. When the voters in New Hampshire went to the polls, Anderson again exceeded the expectations, finishing fourth with just under 10% of the vote.

Anderson was declared the winner in both Massachusetts and Vermont by the Associated Press, but the following morning ended up losing both primaries by a slim margin. In Massachusetts, he lost to George Bush by 0.3% and in Vermont he lost to Reagan by 690 votes. Anderson arrived in Illinois following the New England primaries and had a lead in the state polls, but his Illinois campaign struggled despite endorsements from the state's two largest newspapers. Reagan defeated him, 48% to 37%. Anderson carried Chicago and Rockford, the state's two largest cities at the time, but he lost in the more conservative southern section of the state. The next week, there was a primary in Connecticut, which (while Anderson was on the ballot) his team had chosen not to campaign actively in. He finished third in Connecticut with 22% of the vote, and it seemed to most observers like any other loss, whether Anderson said he was competing or not. Next was Wisconsin, and this was thought to be Anderson's best chance for victory, but he again finished third, winning 27% of the vote.

Independent campaign

The Republican platform failed to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment or support extension of time for its ratification. Anderson was a strong supporter of both. Pollsters were finding that Anderson was much more popular across the country with all voters than he was in the Republican primary states. Without any campaigning, he was running at 22% nationally in a three-way race. Anderson's personal aide and confidant, Tom Wartowski, encouraged him to remain in the Republican Party. Anderson faced a huge number of obstacles as a non-major party candidate: having to qualify for 51 ballots (which the major parties appeared on automatically), having to raise money to run a campaign (the major parties received close to $30 million in government money for their campaigns), having to win national coverage, having to build a campaign overnight, and having to find a suitable running mate among them. He built a new campaign team, qualified for every ballot, raised a great deal of money, and rose in the polls to as high as 26% in one

The Republican platform failed to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment or support extension of time for its ratification. Anderson was a strong supporter of both. Pollsters were finding that Anderson was much more popular across the country with all voters than he was in the Republican primary states. Without any campaigning, he was running at 22% nationally in a three-way race. Anderson's personal aide and confidant, Tom Wartowski, encouraged him to remain in the Republican Party. Anderson faced a huge number of obstacles as a non-major party candidate: having to qualify for 51 ballots (which the major parties appeared on automatically), having to raise money to run a campaign (the major parties received close to $30 million in government money for their campaigns), having to win national coverage, having to build a campaign overnight, and having to find a suitable running mate among them. He built a new campaign team, qualified for every ballot, raised a great deal of money, and rose in the polls to as high as 26% in one Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its ...

.

However, in the summer of 1980, he had an overseas campaign tour to show his foreign policy credentials and it took a drubbing on national television. The major parties, particularly the Republicans, basked in the spotlight of their national conventions where Anderson was left out of the coverage. Anderson made an appearance with Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

and it, too, was a huge error. By the third week of August he was in the 13–15% range in the polls. A critical issue for Anderson was appearing in the fall presidential debates after the League of Women Voters invited him to appear due to popular interest in his candidacy, although he was only polling 12% at that time. In late August, he named Patrick Lucey

Patrick Joseph Lucey (March 21, 1918 – May 10, 2014) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 38th Governor of Wisconsin from 1971 to 1977. He was also independent presidential candidate John B. Anderso ...

, the former two-term Democratic Governor of Wisconsin and Ambassador to Mexico as his running mate. Late in August, Anderson released a 317-page comprehensive platform, under the banner of the National Unity Party, that was very well received. In early September, a court challenge to Federal Election Campaign Act was successful and Anderson qualified for post-election public funding. Also, Anderson submitted his petitions for his fifty-first ballot. Then, the League ruled that the polls showed that he had met the qualification threshold and said he would appear in the debates.

Fall campaign

Carter said that he would not appear on stage with Anderson, and sat out the debate, which hurt the President in the eyes of voters. Reagan and Anderson had adebate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse on a particular topic, often including a moderator and audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for often opposing viewpoints. Debates have historically occurred in public meetings, a ...

in Baltimore on September 21, 1980. Anderson did well, and polls showed he won a modest debate victory over Reagan, but Reagan, who had been portrayed by Carter throughout the campaign as something of a warmonger, proved to be a reasonable candidate and carried himself well in the debate. The debate was Anderson's big opportunity as he needed a break-out performance, but what he got was a modest victory. In the following weeks, Anderson slowly faded out of the picture with his support dropping from 16% to 10–12% in the first half of October. By the end of the month, Reagan debated Carter alone, but CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by ...

attempted to let Anderson participate in the 2nd debate by tape delay. Daniel Schorr

Daniel Louis Schorr (August 31, 1916 – July 23, 2010) was an American journalist who covered world news for more than 60 years. He was most recently a Senior News Analyst for National Public Radio (NPR). Schorr won three Emmy Awards for his te ...

asked Anderson the questions from the Carter-Reagan debate, and then CNN interspersed Anderson's live answers with tape delayed responses from Carter and Reagan.

Anderson's support continued to fade down to 5%, although rose up to 8% just before election day. Although Reagan would win a sizable victory, the polls showed the two major party candidates closer (Gallup's final poll was 47–44–8 going into the election and it was clear that many would-be Anderson supporters had been pulled away by Carter and Reagan. In the end, Anderson finished with 6.6% of the vote. Most of Anderson's support came from those Liberal Republicans who were suspicious of, or even hostile to, Reagan's conservative wing. Many prominent intellectuals, including ''All in the Family

''All in the Family'' is an American television sitcom that aired on CBS for nine seasons, from January 12, 1971, to April 8, 1979. Afterwards, it was continued with the spin-off series ''Archie Bunker's Place'', which picked up where ''All in ...

'' creator Norman Lear, and the editors of the liberal magazine ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'', also endorsed the Anderson campaign. Cartoonist Garry Trudeau

Garretson Beekman Trudeau (born July 21, 1948) is an American cartoonist, best known for creating the '' Doonesbury'' comic strip. Trudeau is also the creator and executive producer of the Amazon Studios political comedy series ''Alpha House'' ...

's ''Doonesbury

''Doonesbury'' is a comic strip by American cartoonist Garry Trudeau that chronicles the adventures and lives of an array of characters of various ages, professions, and backgrounds, from the President of the United States to the title character, ...

'' ran several strips sympathetic to the Anderson campaign. Former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, actor Paul Newman and historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a s ...

have also been reported as having supported Anderson.

Although the Carter campaign feared Anderson could be a spoiler

Spoiler is a security vulnerability on modern computer central processing units that use speculative execution. It exploits side-effects of speculative execution to improve the efficiency of Rowhammer and other related memory and cache attacks. Ac ...

, Anderson's campaign turned out to be "simply another option" for frustrated voters who had already decided not to back Carter for another term. Polls found that around 37% of Anderson voters favored Reagan as their second choice over Carter. Anderson did not carry a single precinct in the country. Anderson's finish was still the best showing for a third-party candidate since George Wallace's 14 percent in 1968 and stands as the seventh best for any such candidate since the Civil War (trailing James B. Weaver's 8.5 percent in 1892, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's 27 percent in 1912, Robert La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

's 17 percent in 1924, Wallace, and Ross Perot's 19 percent and 8 percent in 1992 and 1996, respectively). He pursued Ohio's refusal to provide ballot access to the U.S. Supreme Court and won 5–4 in ''Anderson v. Celebrezze

''Anderson v. Celebrezze'', 460 U.S. 780 (1983), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Ohio's filing deadline for independent candidates was unconstitutional.

Background

John B. Anderson was a declared candidate f ...

''. His inability to make headway against the ''de facto'' two-party system as an independent in that election would later lead him to become an advocate for instant-runoff voting, helping to found FairVote

FairVote, formerly the Center for Voting and Democracy, is a 501(c)(3) organization that advocates electoral reform in the United States.

Founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional r ...

in 1992.

Later career

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students. He capitalized on that by becoming a visiting professor at a series of universities: Stanford University,

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students. He capitalized on that by becoming a visiting professor at a series of universities: Stanford University, University of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8.1 ...

, Duke University, University of Illinois College of Law

The University of Illinois College of Law (Illinois Law or UIUC Law) is the law school of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a public university in Champaign, Illinois. It was established in 1897 and offers the J.D., LL.M., and J.S ...

, Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, ...

, Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh: ) is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Founded as a Quaker institution in 1885, Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, a group of elite, historically women's colleges in the United ...

, Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a public land-grant, research university in Corvallis, Oregon. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate-degree programs along with a variety of graduate and doctoral degrees. It has the 10th largest engineering c ...

, University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst, UMass) is a public research university in Amherst, Massachusetts and the sole public land-grant university in Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Founded in 1863 as an agricultural college, ...

, and Nova Southeastern University

Nova Southeastern University (NSU or, informally, Nova) is a private nonprofit research university with its main campus in Davie, Florida. The university consists of 14 total colleges, centers, and schools offering over 150 programs of study ...

and delivered the lecture at the 1988 Waldo Family Lecture Series on International Relations

The Waldo Family Lecture Series on International Relations is a lecture series which takes place at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. The university's first endowed lecture series was endowed by the Waldo family in 1985 to honor the m ...

at Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University (Old Dominion or ODU) is a public research university in Norfolk, Virginia. It was established in 1930 as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary and is now one of the largest universities in Virginia w ...

. He was chair of FairVote

FairVote, formerly the Center for Voting and Democracy, is a 501(c)(3) organization that advocates electoral reform in the United States.

Founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional r ...

from 1996 to 2008, after helping to found the organization in 1992, and continued to serve on its board until 2014. He also served as president of the World Federalist Association

Citizens for Global Solutions is a grassroots membership organization in the United States.

History

Five world federalist organizations merged in 1947 to form the United World Federalists, Inc., later renamed World Federalists-USA. In 1975, ...

and on the advisory board of Public Campaign

Every Voice is an American nonprofit, progressive liberal political advocacy organization.

and the Electronic Privacy Information Center

Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) is an independent nonprofit research center in Washington, D.C. EPIC's mission is to focus public attention on emerging privacy and related human rights issues. EPIC works to protect privacy, freedom ...

, and was of counsel to the Washington, D.C.-based law firm of Greenberg & Lieberman

Greenberg & Lieberman is a national and international law firm based in Washington, D.C. Established in 1996 by Michael Greenberg and Stevan Lieberman, the firm is known for its expertise in the technology-law areas of intellectual property, tr ...

, LLC.

He was the first executive director of the Council for the National Interest The Council for the National Interest ("CNI") is a 501(c)(4) non-profit, non-partisan anti-war advocacy group focused on transparency and accountability about the relationship of Israel and the United States and the impact their alliance has for o ...

, founded in 1989 by former Congressmen Paul Findley

Paul Augustus Findley (June 23, 1921 – August 9, 2019) was an American writer and politician. He served as United States Representative from Illinois, representing its 20th District. A Republican, he was first elected in 1960. A moderate Rep ...

(R-IL) and Pete McCloskey

Paul Norton McCloskey Jr. (born September 29, 1927) is an American politician who represented San Mateo County, California as a Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1983.

Born in Loma Linda, California, McCloskey pursue ...

(R-CA) to promote American interests in the Middle East. In the 2000 U.S. presidential election, he was briefly considered as possible candidate for the Reform Party nomination, but instead endorsed Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the U ...

, who was nominated by the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

. In January 2008, Anderson indicated strong support for the candidacy of a fellow Illinoisan, Democratic contender Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

. In 2012, he played a role in the creation of the Justice Party, a progressive, social-democratic party organized to support the candidacy of former Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

mayor Rocky Anderson

Ross Carl "Rocky" Anderson (born September 9, 1951), from the United States, is an attorney, writer, activist, civil and human rights advocate. He served two terms as the 33rd Mayor of Salt Lake City, Utah from 2000 to 2008. He is now running f ...

(no relation) for the 2012 U.S. presidential election. On August 6, 2014, he endorsed the campaign for the United Nations Parliamentary Assembly

A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is a proposed addition to the United Nations System that would allow for greater participation and voice for members of parliament. The idea was raised at the founding of the League of Nations in ...

(UNPA), one of only six persons who served in the United States Congress ever to do so.

Death

Anderson died in Washington, D.C. on December 3, 2017, at the age of 95. He was interred atArlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

on June 22, 2018.

See also

* ''Anderson v. Celebrezze

''Anderson v. Celebrezze'', 460 U.S. 780 (1983), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Ohio's filing deadline for independent candidates was unconstitutional.

Background

John B. Anderson was a declared candidate f ...

''

* Third party (United States)

Third party is a term used in the United States for American political parties other than the two dominant parties, currently the Republican and Democratic Parties. Sometimes the phrase "minor party" is used instead of third party.

Third parti ...

References

Citations

Sources

* * *External links

*Arlington National Cemetery

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Anderson, John B. 1922 births 2017 deaths 20th-century American politicians United States Army personnel of World War II American people of Swedish descent Centrism in the United States Harvard Law School alumni Brandeis University faculty Burials at Arlington National Cemetery District attorneys in Illinois Duke University faculty Illinois Independents Members of the Evangelical Free Church of America Military personnel from Illinois Oregon State University faculty Politicians from Rockford, Illinois Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois United States Army non-commissioned officers Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election University of Illinois College of Law alumni University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty