John Armstrong, Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Armstrong Jr. (November 25, 1758April 1, 1843) was an

In 1789, Armstrong married Alida Livingston (1761–1822), the youngest child of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (

In 1789, Armstrong married Alida Livingston (1761–1822), the youngest child of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (

Lewis, John N., "Town of Red Hook", ''History of Dutchess County'', (Frank Hasbrouck, ed.), Higginson Book Company, 1909

/ref>

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

soldier, diplomat and statesman who was a delegate to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

under President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

, Armstrong was United States Minister to France

The United States ambassador to France is the official representative of the president of the United States to the president of France. The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with France since the American Revolution. Relations we ...

from 1804 to 1810.

Early life

Armstrong was born inCarlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 census, the borough population was 20,118; ...

, the younger son of General John Armstrong and Rebecca (Lyon) Armstrong. John Armstrong Sr. was a renowned Pennsylvania soldier born in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

of Scottish descent. John Jr.'s older brother was James Armstrong, who became a physician and U.S. Congressman.

After early education in Carlisle, John Jr. studied at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

). He broke off his studies in Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

in 1775 to return to Pennsylvania and join the fight in the Revolutionary War.

Career

Revolutionary War

The young Armstrong initially joined a Pennsylvania militia regiment and the following year he was appointed as aide-de-camp to General Hugh Mercer of theContinental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. In this role, he carried the wounded and dying General Mercer from the field at the Battle of Princeton

The Battle of Princeton was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, fought near Princeton, New Jersey on January 3, 1777, and ending in a small victory for the Colonials. General Lord Cornwallis had left 1,400 British troops under the comm ...

. After the general died on January 12, 1777, Armstrong became an aide to General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battl ...

. He stayed with Gates through the Battle of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign, giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne led an invasion ...

then resigned due to problems with his health. In 1782 Gates asked him to return. Armstrong joined General Gates' staff as an aide with the rank of major, which he held through the rest of the war.

Newburgh letters

While in camp with Gates atNewburgh, New York

Newburgh is a city in the U.S. state of New York, within Orange County. With a population of 28,856 as of the 2020 census, it is a principal city of the Poughkeepsie–Newburgh–Middletown metropolitan area. Located north of New York City, a ...

, Armstrong became involved in the Newburgh Conspiracy. He is generally acknowledged as the author of the two anonymous letters directed at the officers in the camp. The first, titled "An Address to the Officers" (dated March 10, 1783), called for a meeting to discuss back pay and other grievances with the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and form a plan of action. After George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

ordered the meeting canceled and called for a milder meeting on March 15, a second address appeared that claimed that this showed that Washington supported their actions.

Washington successfully defused this protest without a mutiny. While some of Armstrong's later correspondence acknowledged his role, there was never any official action that connected him with the anonymous letters.

After the revolution

Later in 1783 Armstrong returned home to Carlisle and became an Original Member of the PennsylvaniaSociety of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

. He was named the Adjutant General of Pennsylvania's militia and also served as Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

The secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (or "secretary of state") administers the Pennsylvania Department of State of the U.S. state (officially, "commonwealth") of Pennsylvania. The secretary is appointed by the governor subject to ...

under Presidents Dickinson and Franklin. In 1784, he led a military force of four hundred militiamen into a controversy with Connecticut settlers in the Wyoming Valley

The Wyoming Valley is a historic industrialized region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The region is historically notable for its influence in helping fuel the American Industrial Revolution with its many anthracite coal-mines. As a metropolitan ...

of Pennsylvania. His tactics enraged the nearby states of Vermont and Connecticut, which sent their own militia into the area. Timothy Pickering

Timothy Pickering (July 17, 1745January 29, 1829) was the third United States Secretary of State under Presidents George Washington and John Adams. He also represented Massachusetts in both houses of Congress as a member of the Federalist Pa ...

was dispatched to forge a solution to the difficulty, and the settlers were able to keep title to the land they had tamed. In 1787 and 1788 Armstrong was sent as a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

. The Congress offered to make him chief justice of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. He declined this, as well as all other public offices for the next dozen years.

Armstrong resumed public life after the resignation of John Laurance

John Laurance (sometimes spelled "Lawrence" or "Laurence") (1750 – November 11, 1810) was a delegate to the 6th, 7th, and 8th Congresses of the Confederation, a United States representative and United States Senator from New York and a Unite ...

as U.S. Senator from New York

Below is a list of U.S. senators who have represented the State of New York in the United States Senate since 1789. The date of the start of the tenure is either the first day of the legislative term (Senators who were elected regularly before th ...

. As a Jeffersonian Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

he was elected in November 1800 to a term ending in March 1801. He took his seat on November 6, and was re-elected on January 27 for a full term (1801–07), but resigned on February 5, 1802. DeWitt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and naturalist. He served as a United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the seventh governor of New York. In this last capacity, he was largely re ...

was elected to fill the vacancy, but resigned in 1803, and Armstrong was appointed temporarily to his old seat.

In February 1804, Armstrong was elected again to the U.S. Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Theodorus Bailey, thus moving from the Class 3 to the Class 1 seat on February 25, but served only four months before President Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

appointed him U.S. Minister to France.

To Paris Armstrong brought as his private secretary the United-Irish exile, David Bailie Warden

David Bailie Warden was a republican insurgent in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and, in later exile, a United States consul in Paris. While in American service Watson protested the corruption of diplomatic service by the "avaricious" spirit of com ...

. After serving as Consul, Warden was to author the first major work of reference for the diplomatic corps; a "pioneering" contribution to "the emergence of doctrinal views and a specialist literature on international law".

Armstrong served as Minister in Paris until September 1810. In 1806 he had also briefly also represented the United States at the court of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

.

When the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

broke out, Armstrong was called to military service. He was commissioned as a Brigadier General, and placed in charge of the defenses for the port of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. Then in 1813 President Madison named him Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

.

Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fran ...

wrote of him:

''In spite of Armstrong's services, abilities, and experience, something in his character always created distrust. He had every advantage of education, social and political connection, ability and self-confidence; he was only fifty-four years old, which was also the age of Monroe; but he suffered from the reputation of indolence and intrigue. So strong was the prejudice against him that he obtained only eighteen votes against fifteen in the Senate on his confirmation; and while the two senators from Virginia did not vote at all, the two from Kentucky voted in the negative. Under such circumstances, nothing but military success of the first order could secure a fair field for Monroe's rival.'' Armstrong made a number of valuable changes to the armed forces but was so convinced that the British would 'not' attack Washington D.C. that he did nothing to defend the city even when it became clear it was the objective of the invasion force. After the American defeat at the

Battle of Bladensburg

The Battle of Bladensburg was a battle of the Chesapeake campaign of the War of 1812, fought on 24 August 1814 at Bladensburg, Maryland, northeast of Washington, D.C.

Called "the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms," a British for ...

and the subsequent burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington was a British invasion of Washington City (now Washington, D.C.), the capital of the United States, during the Chesapeake Campaign of the War of 1812. It is the only time since the American Revolutionary War that a ...

, Madison, usually a forgiving man, forced him to resign in September 1814.

Later life

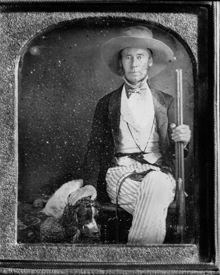

Armstrong returned to his farm and resumed a quiet life. He published a number of histories, biographies, and some works on agriculture. He died at La Bergerie (later renamed Rokeby), the farm estate he built inRed Hook, New York

Red Hook is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States. The population was 9,953 at the time of the 2020 census, down from 11,319 in 2010. The name is supposedly derived from the red foliage on trees on a small strip of land on the Huds ...

in 1843 and is buried in the cemetery in Rhinebeck. Following the death of Paine Wingate in 1838, he became the last surviving delegate to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, and the only one to be photographed.

Personal life

In 1789, Armstrong married Alida Livingston (1761–1822), the youngest child of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (

In 1789, Armstrong married Alida Livingston (1761–1822), the youngest child of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Beekman) Livingston. Alida was also the sister of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

and Edward Livingston

Edward Livingston (May 28, 1764May 23, 1836) was an American jurist and statesman. He was an influential figure in the drafting of the Louisiana Civil Code of 1825, a civil code based largely on the Napoleonic Code. Livingston represented bot ...

. Together they had seven children:

* Maj Horatio Gates Armstrong (1790–1858), soldier in the War of 1812.

* Henry Beekman Armstrong (1791–1854), also a soldier in the War of 1812.

* John Armstrong (1794–1852), who moved to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and took up life as a gentleman farmer at La Bergerie, a farm purchased from her family in Dutchess County

Dutchess County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 295,911. The county seat is the city of Poughkeepsie. The county was created in 1683, one of New York's first twelve counties, and later or ...

* Robert Livingston Armstrong (1797–1834)

* Margaret Rebecca Armstrong (1800–1872), who married William Backhouse Astor Sr.

William Backhouse Astor Sr. (September 19, 1792 – November 24, 1875) was an American business magnate who inherited most of his father John Jacob Astor's fortune. He worked as a partner in his father's successful export business. His massive in ...

(1792–1875) of the prominent Astor family

The Astor family achieved prominence in business, society, and politics in the United States and the United Kingdom during the 19th and 20th centuries. With ancestral roots in the Italian Alps region of Italy by way of Germany,

the Astors settled ...

.

* James Kosciuszko Armstrong (1801–1868)

* William Armstrong (1814–1902), who married Lucy A. Hickernell (1816–1894).

Armstrong died in Red Hook, New York

Red Hook is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States. The population was 9,953 at the time of the 2020 census, down from 11,319 in 2010. The name is supposedly derived from the red foliage on trees on a small strip of land on the Huds ...

on April 1, 1843. He was buried at the Rhinebeck Cemetery in Rhinebeck, New York

Rhinebeck is a village in the town of Rhinebeck in Dutchess County, New York, United States. The population was 2,657 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Poughkeepsie– Newburgh– Middletown, NY Metropolitan Statistical Area as well ...

.

Residences

Almont

Armstrong's initial farm in Dutchess County, called "Altmont" (also known as "The Meadows"), was originally part of the Schuyler patent. In 1795, he purchased a part of the farm from the Van Benthuysen family, and converted an existing barn into a two-story Federal style dwelling with twelve rooms. Around 1800, Armstrong sold "Almont" toAndrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derive ...

and Anna Verplanck Deveaux. Deveaux died in 1812; in 1816 his widow sold "Deveaux Park" to John Stevens. The mansion burned down around 1879. In 1908, lumber rights to the white oak and chestnut forests were sold for timber for the New York market./ref>

La Bergerie

After the death of Margaret Beekman Livingston, widow of Judge Robert Livingston, much of the Clermont land was distributed among the heirs. John R. Livingston received the land that would become the "Messena" estate. His sister Alida Livingston Armstrong inherited the property just to the south. There the Armstrong's created "La Bergerie", in English "the sheepfold" – an estate where they raised Merino sheep. The Merino sheep were a gift from the French EmperorNapoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

on Armstrong's departure after being Minister. The Astors purchased it for a summer home and renamed it Rokeby. Margaret Chanler Aldrich, great-granddaughter of Margaret Armstrong Astor, married Richard Aldrich. Rokeby remains in the Aldrich family.

See also

*Rokeby (Barrytown, New York)

Rokeby, also known as La Bergerie, is a historic estate and federally recognized historic district located at Barrytown in Dutchess County, New York, United States. It includes seven contributing buildings and one contributing structure.

History

...

References

Further reading

* Skeen, Carl E. ''John Armstrong Jr., 1758–1843: A Biography.'' Syracuse Univ Press, 1982. .External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Armstrong, John Jr. 1758 births 1843 deaths People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania People of colonial Pennsylvania Livingston family American people of Scotch-Irish descent Madison administration cabinet members United States Secretaries of War Continental Congressmen from Pennsylvania Democratic-Republican Party United States senators from New York (state) Ambassadors of the United States to France 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians 19th-century American diplomats United States Army generals Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania United States Army personnel of the War of 1812