John Addington Symonds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

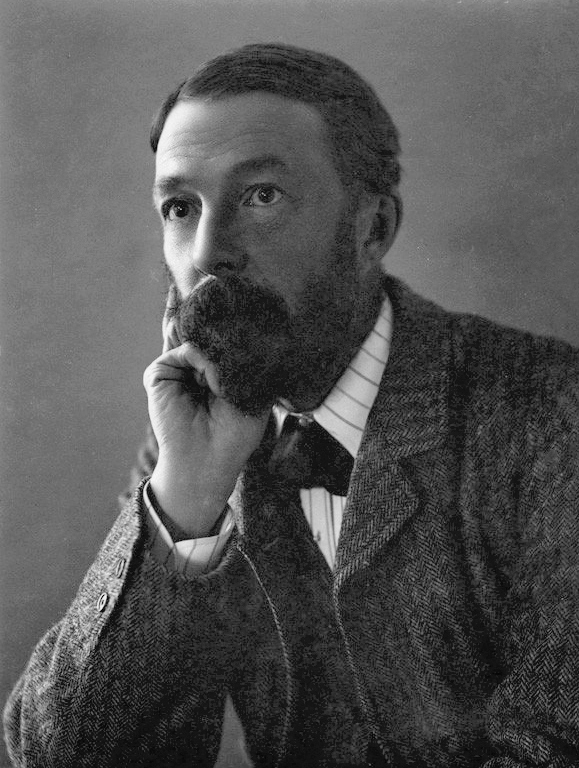

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the

While in Clifton in 1868, Symonds met and fell in love with Norman Moor (January 10, 1851 – March 6, 1895), a youth about to go up to Oxford, who became his pupil. Symonds and Moor had a four-year affair but did not have sex, although according to Symonds's diary of 28 January 1870, "I stripped him naked and fed sight, touch and mouth on these things." The relationship occupied a good part of his time, including one occasion he left his family and travelled to Italy and Switzerland with Moor. The unconsummated affair also inspired his most productive period of composing poetry, published in 1880 as ''New and Old: A Volume of Verse''.

While in Clifton in 1868, Symonds met and fell in love with Norman Moor (January 10, 1851 – March 6, 1895), a youth about to go up to Oxford, who became his pupil. Symonds and Moor had a four-year affair but did not have sex, although according to Symonds's diary of 28 January 1870, "I stripped him naked and fed sight, touch and mouth on these things." The relationship occupied a good part of his time, including one occasion he left his family and travelled to Italy and Switzerland with Moor. The unconsummated affair also inspired his most productive period of composing poetry, published in 1880 as ''New and Old: A Volume of Verse''.

"Introduction: (Re)Reading John Addington Symonds"

Special Issue of ''English Studies'', 94:2 (2013). * Amber K. Regis (ed.), ''The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition'' (2016)

Downing, Ben, "John Addington Symonds & Janet Ross: a friendship," ''The New Criterion'', November 2011.

John Addington Symonds papers

, University of Bristol Library Special Collections

Symonds's translation of ''The Life of Benvenuto Cellini,'' Vol. 1

Posner Library, Carnegie Mellon Universit

Vol. 2

Carnegie Mellon University

John Addington Symonds, ''Waste: a lecture delivered at the Bristol institution for the advancement of science, literature...''

1863

John Addington Symonds, ''The Principles of Beauty''

1857

John Addington Symonds, ''The Renaissance, an essay''

1863

''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 9th edition, 1875–89, 1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

''GLBTQ encyclopaedia''

1998 Symonds International Symposium

2010 Symonds International Symposium

Michael Matthew Kaylor, ''Secreted Desires: The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde'' (2006)

Indiana University *David Beres

Review of ''The Letters of John Addington Symonds'', ed. Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters

'' Psychoanalytic Quarterly'' 40 (1971)

Rictor Norton, "The Life and Writings of John Addington Symonds (1840—1893)"John Addington Symonds Project

Classics Research Lab at Johns Hopkins University {{DEFAULTSORT:Symonds, John Addington 1840 births 1893 deaths English literary critics Writers from Bristol British gay writers People educated at Harrow School LGBT rights activists from England Burials in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome Victorian writers 19th-century British writers English LGBT poets 19th-century British journalists British male journalists English male poets English expatriates in Switzerland English expatriates in Italy People from Clifton, Bristol Bisexual academics

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although married with children, Symonds supported male love (homosexuality

Homosexuality is Romance (love), romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romant ...

), which he believed could include pederastic as well as egalitarian relationships, referring to it as ''l'amour de l'impossible'' (love of the impossible). He also wrote much poetry inspired by his same-sex affairs.

Early life and education

Symonds was born atBristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, England, in 1840. His father, the physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

John Addington Symonds, Sr. (1807–1871), was the author of ''Criminal Responsibility'' (1869), ''The Principles of Beauty'' (1857) and ''Sleep and Dreams''. The younger Symonds, considered delicate, did not take part in games at Harrow School after the age of 14, and he showed no particular promise as a scholar. Symonds moved to Clifton Hill House

Clifton Hill House is a Grade I listed Palladian villa in the Clifton area of Bristol, England. It was the first hall of residence for women in south-west England in 1909 due to the efforts of May Staveley. It is still used as a hall of resi ...

at the age of ten, an event which he believed had a large and beneficial impact towards his health and spiritual development. Symonds's delicate condition continued, and as a child he suffered from nightmares in which corpses in and under his bed prompted sleepwalking; on one such occasion he was almost drowned when, sleepwalking in the attic of Clifton Hill House, he reached a cistern of rainwater. According to Symonds, an angel with "blue eyes and wavy, blonde hair" woke him and brought him to safety; this figure frequented Symonds's dreams and was potentially his first homosexual awakening.

In January 1858, Symonds received a letter from his friend Alfred Pretor (1840–1908), telling of Pretor's affair with their headmaster, Charles John Vaughan

Charles John Vaughan (16 August 1816 – 15 October 1897) was an English scholar and Anglican churchman.

Life

He was born in Leicester, the second son of the Revd Edward Thomas Vaughan, vicar of St Martin's, Leicester. He was educated at Ru ...

. Symonds was shocked and disgusted, feelings complicated by his growing awareness of his own homosexuality. He did not mention the incident for more than a year until in 1859, when a student at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, he told the story to John Conington, the Latin professor. Conington approved of romantic relationships between men and boys. Earlier, he had given Symonds a copy of ''Ionica'', a collection of homoerotic verse by William Johnson Cory, the influential Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

master and advocate of pederastic pedagogy. Conington encouraged Symonds to tell his father about his friend's affair, and the senior Symonds forced Vaughan to resign from Harrow. Pretor was angered by the younger man's part, and never spoke to Symonds again.

In the autumn of 1858, Symonds went to Balliol College, Oxford, as a commoner but was elected to an exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibitio ...

in the following year. In spring of that same year, he fell in love with William Fear Dyer (1843–1905), a Bristol choirboy three years younger. They engaged in a chaste love affair that lasted a year, until broken up by Symonds. The friendship continued for several years afterwards, until at least 1864. Dyer became organist and choirmaster of St Nicholas' Church, Bristol.

At Oxford University, Symonds became engaged in his studies and began to demonstrate his academic ability. In 1860, he took a first in Mods and won the Newdigate prize with a poem on "The Escorial"; in 1862 he obtained a first in '' Literae Humaniores'', and in 1863 won the Chancellor's English Essay.

In 1862, Symonds was elected to an open fellowship at the conservative Magdalen. He made friends with a C. G. H. Shorting, whom he took as a private pupil. When Symonds refused to help Shorting gain admission to Magdalen, the younger man wrote to school officials alleging "that I ymondshad supported him in his pursuit of the chorister Walter Thomas Goolden (1848–1901), that I shared his habits and was bent on the same path." Although Symonds was officially cleared of any wrongdoing, he suffered a breakdown from the stress and shortly thereafter left the university for Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

Personal life

In Switzerland, he met Janet Catherine North (sister of botanical artistMarianne North

Marianne North (24 October 1830 – 30 August 1890) was a prolific English Victorian biologist and botanical artist, notable for her plant and landscape paintings, her extensive foreign travels, her writings, her plant discoveries and the ...

, 1830–1890). They married at Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

on 10 November 1864. They settled in London and had four daughters: Janet (born 1865), Charlotte (born 1867), Margaret (Madge) (born 1869) and Katharine (born 1875; she was later honoured for her writing as Dame Katharine Furse

Dame Katharine Furse, ( Symonds; 23 November 1875 – 25 November 1952) was a British nursing and military administrator. She led the British Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment force during the First World War, and served as the inaugural Dire ...

). Edward Lear wrote " The Owl and the Pussycat" for the three-year-old Janet.

While in Clifton in 1868, Symonds met and fell in love with Norman Moor (January 10, 1851 – March 6, 1895), a youth about to go up to Oxford, who became his pupil. Symonds and Moor had a four-year affair but did not have sex, although according to Symonds's diary of 28 January 1870, "I stripped him naked and fed sight, touch and mouth on these things." The relationship occupied a good part of his time, including one occasion he left his family and travelled to Italy and Switzerland with Moor. The unconsummated affair also inspired his most productive period of composing poetry, published in 1880 as ''New and Old: A Volume of Verse''.

While in Clifton in 1868, Symonds met and fell in love with Norman Moor (January 10, 1851 – March 6, 1895), a youth about to go up to Oxford, who became his pupil. Symonds and Moor had a four-year affair but did not have sex, although according to Symonds's diary of 28 January 1870, "I stripped him naked and fed sight, touch and mouth on these things." The relationship occupied a good part of his time, including one occasion he left his family and travelled to Italy and Switzerland with Moor. The unconsummated affair also inspired his most productive period of composing poetry, published in 1880 as ''New and Old: A Volume of Verse''.

Career

Symonds intended to study law, but his health again broke down and forced him to travel. Returning to Clifton, he lectured there, both at the college and ladies' schools. From his lectures, he prepared the essays in his ''Introduction to the Study of Dante'' (1872) and ''Studies of the Greek Poets'' (1873–1876). Meanwhile, he was occupied with his major work, ''Renaissance in Italy'', which appeared in seven volumes at intervals between 1875 and 1886. Since his prize essay on theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

at Oxford, Symonds had wanted to study it further and emphasise the reawakening of art and literature in Europe. His work was interrupted by serious illness. In 1877 his life was in danger. His recovery at Davos Platz led him to believe this was the only place where he was likely to enjoy life.

He practically made his home at Davos, and wrote about it in ''Our Life in the Swiss Highlands'' (1891). Symonds became a citizen of the town; he took part in its municipal business, made friends with the peasants, and shared their interests. There he wrote most of his books: biographies of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

(1878), Philip Sidney

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

(1886), Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

(1886) and Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was ins ...

(1893), several volumes of poetry and essays, and a translation of the ''Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini'' (1887).

There, too, he completed his study of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, the work for which he is chiefly remembered. He was feverishly active throughout his life. Considering his poor health, his productivity was remarkable. Two works, a volume of essays, ''In the Key of Blue'', and a monograph on Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

, were published in the year of his death. His activity was unbroken to the last.

He had a passion for Italy, and for many years resided during the autumn in the house of his friend, Horatio F. Brown, on the Zattere, in Venice. In 1891 he made an effort to visit Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in L'Aquila. He died in Rome and was buried close to the grave of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

.

Legacy

Symonds left his papers and his autobiography in the hands of Brown, who wrote an expurgated biography in 1895, whichEdmund Gosse

Sir Edmund William Gosse (; 21 September 184916 May 1928) was an English poet, author and critic. He was strictly brought up in a small Protestant sect, the Plymouth Brethren, but broke away sharply from that faith. His account of his childhoo ...

further stripped of homoerotic content before publication. In 1926, upon coming into the possession of Symonds's papers, Gosse burned everything except the memoirs, to the dismay of Symonds's granddaughter.

Symonds was morbidly introspective, but with a capacity for action. In ''Talks and Talkers'', the contemporary writer Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as '' Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

described Symonds (known as "Opalstein" in Stevenson's essay) as "the best of talkers, singing the praises of the earth and the arts, flowers and jewels, wine and music, in a moonlight, serenading manner, as to the light guitar." Beneath his good fellowship, he was a melancholic.

This side of his nature is revealed in his gnomic poetry, and particularly in the sonnets of his ''Animi Figura'' (1882). He portrayed his own character with great subtlety. His poetry is perhaps rather that of the student than of the inspired singer, but it has moments of deep thought and emotion.

It is, indeed, in passages and extracts that Symonds appears at his best. Rich in description, full of "purple patch

In literary criticism, purple prose is overly ornate prose text that may disrupt a narrative flow by drawing undesirable attention to its own extravagant style of writing, thereby diminishing the appreciation of the prose overall. Purple prose ...

es", his work lacks the harmony and unity essential to the conduct of philosophical argument. His translations are among the finest in the language; here his subject was found for him, and he was able to lavish on it the wealth of colour and quick sympathy which were his characteristics.

Homosexual writings

In 1873, Symonds wrote ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'', a work of what would later be called "gay history

Societal attitudes towards same-sex relationships have varied over time and place, from requiring all males to engage in same-sex relationships to casual integration, through acceptance, to seeing the practice as a minor sin, repressing it throu ...

". He was inspired by the poetry of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

, with whom he corresponded. The work, "perhaps the most exhaustive eulogy of Greek love

''Greek love'' is a term originally used by classicists to describe the primarily homoerotic customs, practices, and attitudes of the ancient Greeks. It was frequently used as a euphemism for homosexuality and pederasty. The phrase is a produc ...

," remained unpublished for a decade, and then was printed at first only in a limited edition for private distribution. Although the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a c ...

'' credits the medical writer C. G. Chaddock for introducing "homosexual" into the English language in 1892, Symonds had already used the word in ''A Problem in Greek Ethics''. Aware of the taboo nature of his subject matter, Symonds referred obliquely to pederasty as "that unmentionable custom" in a letter to a prospective reader of the book, but defined "Greek love" in the essay itself as "a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness."

Symonds studied classics under Benjamin Jowett at Balliol College, Oxford, and later worked with Jowett on an English translation of Plato's ''Symposium''. Aldrich, Robert (1993) ''The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art, and Homosexual Fantasy''. Routledge. 0415093120. p. 78. Jowett was critical of Symonds's opinions on sexuality, but when Symonds was falsely accused of corrupting choirboys, Jowett supported him, despite his own equivocal views of the relation of Hellenism to contemporary legal and social issues that affected homosexuals.

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as ''Eudiades'', which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems". While the taboos of Victorian England prevented Symonds from speaking openly about homosexuality, his works published for a general audience contained strong implications and some of the first direct references to male-male sexual love in English literature. For example, in "The Meeting of David and Jonathan

David and Jonathan were, according to the Hebrew Bible's Books of Samuel, heroic figures of the Kingdom of Israel, who formed a covenant, taking a mutual oath.

Jonathan was the son of Saul, king of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, and David ...

", from 1878, Jonathan takes David "In his arms of strength / ndin that kiss / Soul into soul was knit and bliss to bliss". The same year, his translations of Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was ins ...

's sonnets to the painter's beloved Tommaso Cavalieri restore the male pronouns which had been made female by previous editors. In November 2016, Symonds's homoerotic poem, 'The Song of the Swimmer', written in 1867, was published for the first time in the '' Times Literary Supplement''.

By the end of his life, Symonds's bisexuality had become an open secret in certain literary and cultural circles. His private memoirs, written (but never completed) over a four-year period from 1889 to 1893, form the earliest known self-conscious LGBT autobiography.

Symonds's daughter, Madge Vaughan, was probably writer Virginia Woolf's first same-sex crush, though there is no evidence that the feeling was mutual. Woolf was the cousin of her husband William Wyamar Vaughan William Wyamar Vaughan (25 February 1865 - 4 February 1938) was a British educationalist.

Vaughan was the son of Sir Henry Halford Vaughan, Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford. His mother Adeline Maria Jackson was Julia Stephen's older s ...

. Another daughter, Charlotte Symonds, married the classicist Walter Leaf. Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

used some details of Symonds's life, especially the relationship between him and his wife, as the starting-point for the short story " The Author of Beltraffio" (1884).

Over a century after Symonds's death, in 2007, his first work on homosexuality, ''Soldier Love and Related Matter,'' was finally published by Andrew Dakyns (grandson of Symonds' associate, Henry Graham Dakyns

Henry Graham Dakyns, often H. G. Dakyns (1838–1911), was a British translator of Ancient Greek, best known for his translations of Xenophon: the ''Cyropaedia'' and '' Hellenica'', '' The Economist'', '' Hiero'' and '' On Horsemanship''.

Life

...

), in Eastbourne, E. Sussex, England. ''Soldier Love'', or ''Soldatenliebe'' since it was limited to a German edition. Symonds' English text is lost. This translation and edition by Dakyns is the only version ever to appear in the author's own language.

Works

* ''The Renaissance. An Essay'' (1863) * ''Miscellanies by John Addington Symonds, M.D.,: Selected and Edited with an Introductory Memoir, by His Son'' (1871) * ''Introduction to the Study of Dante'' (1872) * ''Studies of the Greek Poets'', 2 vol. (1873, 1876) * ''Renaissance in Italy'', 7 vol. (1875–86) * ''Shelley'' (1878) * ''Sketches in Italy and Greece'' (London, Smith and Elder 1879) * ''Sketches and Studies in Italy'' (London, Smith and Elder 1879) * ''Animi Figura'' (1882) * ''Sketches in Italy'' (Selections prepared by Symonds, arranged, so as to, in his own words in a Prefatory Note, "adapt itself to the use of travellers rather than of students"; Leipzig,Bernhard Tauchnitz

Christian Bernhard Tauchnitz (August 25, 1816 – August 13, 1895) was a German publisher.

Biography

He was born near Naumburg, a nephew of Karl Christoph Traugott Tauchnitz. His firm, founded in Leipzig in 1837, was noted for its accurate class ...

1883)

* ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'' (1883)

* ''Shakspere's Predecessors in the English Drama'' (1884)

* ''New Italian Sketches'' (Bernard Tauchnitz: Leipzig, 1884)

* ''Wine, Women, and Song. Medieval Latin Students' Songs'' (1884) English translations/paraphrases.

* ''Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini'' (1887) An English translation.

* ''A Problem in Modern Ethics'' (1891)

* ''Our Life in the Swiss Highlands'' (1892) (with his daughter Margaret Symonds as coauthor)

* ''Essays: Speculative and Suggestive'' (1893)

* ''In the Key of Blue'' (1893)

* ''The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti'' (1893)

* ''Walt Whitman. A Study'' (1893)

See also

*Uranian poetry

The Uranians were a 19th-century clandestine group of up to several dozen male homosexual poets and prose writers who principally wrote on the subject of the love of (or by) adolescent boys. In a strict definition they were an English literary an ...

Notes

References

* * *Further reading

*Phyllis Grosskurth

Phyllis M. Grosskurth (March 16, 1924 – August 2, 2015) was a Canadian academic, writer, and literary critic.

Born in Toronto, Ontario, she received a Bachelor of Arts honours degree in English from the University of Toronto and later a Ma ...

, ''John Addington Symonds: A Biography'' (1964)

* Phyllis Grosskurth

Phyllis M. Grosskurth (March 16, 1924 – August 2, 2015) was a Canadian academic, writer, and literary critic.

Born in Toronto, Ontario, she received a Bachelor of Arts honours degree in English from the University of Toronto and later a Ma ...

(ed.), ''The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds'' Hutchinson (1984)

* Whitney Davis, ''Queer Beauty'', chapter 4: "Double Mind: Hegel, Symonds, and Homoerotic Spirit in Renaissance Art". Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fie ...

, 2010.

* David Amigoni and Amber K. Regis (eds.)"Introduction: (Re)Reading John Addington Symonds"

Special Issue of ''English Studies'', 94:2 (2013). * Amber K. Regis (ed.), ''The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition'' (2016)

Downing, Ben, "John Addington Symonds & Janet Ross: a friendship," ''The New Criterion'', November 2011.

External links

* * *John Addington Symonds papers

, University of Bristol Library Special Collections

Symonds's translation of ''The Life of Benvenuto Cellini,'' Vol. 1

Posner Library, Carnegie Mellon Universit

Vol. 2

Carnegie Mellon University

John Addington Symonds, ''Waste: a lecture delivered at the Bristol institution for the advancement of science, literature...''

1863

John Addington Symonds, ''The Principles of Beauty''

1857

John Addington Symonds, ''The Renaissance, an essay''

1863

''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 9th edition, 1875–89, 1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

''GLBTQ encyclopaedia''

1998 Symonds International Symposium

2010 Symonds International Symposium

Michael Matthew Kaylor, ''Secreted Desires: The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde'' (2006)

Indiana University *David Beres

Review of ''The Letters of John Addington Symonds'', ed. Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters

'' Psychoanalytic Quarterly'' 40 (1971)

Rictor Norton, "The Life and Writings of John Addington Symonds (1840—1893)"

Classics Research Lab at Johns Hopkins University {{DEFAULTSORT:Symonds, John Addington 1840 births 1893 deaths English literary critics Writers from Bristol British gay writers People educated at Harrow School LGBT rights activists from England Burials in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome Victorian writers 19th-century British writers English LGBT poets 19th-century British journalists British male journalists English male poets English expatriates in Switzerland English expatriates in Italy People from Clifton, Bristol Bisexual academics