Jo Cox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Helen Joanne Cox ( Leadbeater; 22 June 1974 – 16 June 2016) was a British politician who served as

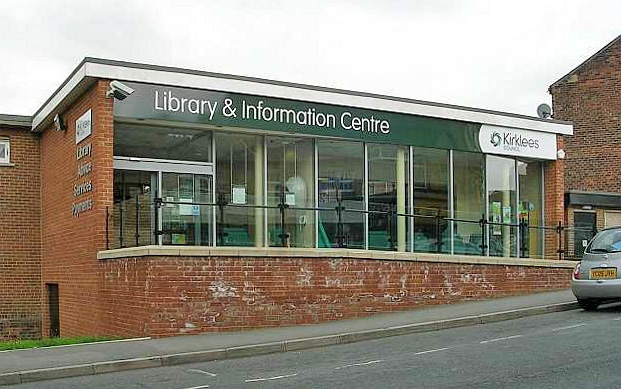

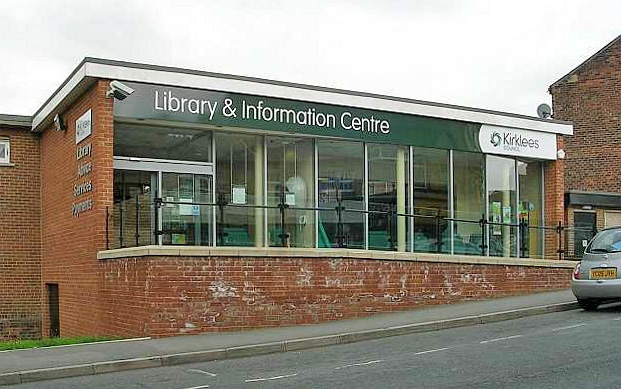

At 12:53 pm BST on Thursday, 16 June 2016, Cox was fatally shot and stabbed outside a library in Birstall, West Yorkshire, where she was about to hold a

At 12:53 pm BST on Thursday, 16 June 2016, Cox was fatally shot and stabbed outside a library in Birstall, West Yorkshire, where she was about to hold a  Mair was arrested shortly after the attack. In a statement issued the day after the attack, West Yorkshire Police said that Cox was the victim of a "targeted attack" and the suspect's links to far-right extremism were a "priority line of inquiry" in the search for a motive. Mair was also examined by a psychiatrist who concluded that Mair was responsible for his actions and that poor mental health was not the consequent factor for his attacks. On 18 June, Mair was charged with murder,

Mair was arrested shortly after the attack. In a statement issued the day after the attack, West Yorkshire Police said that Cox was the victim of a "targeted attack" and the suspect's links to far-right extremism were a "priority line of inquiry" in the search for a motive. Mair was also examined by a psychiatrist who concluded that Mair was responsible for his actions and that poor mental health was not the consequent factor for his attacks. On 18 June, Mair was charged with murder,

A street, formerly the after Pierre-Étienne Flandin, in Avallon, a town in the Yonne ' of France, was renamed the in May 2017. In

A street, formerly the after Pierre-Étienne Flandin, in Avallon, a town in the Yonne ' of France, was renamed the in May 2017. In

Jo Cox Foundation

a charity established in memory of Jo Cox.

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for Batley and Spen

Batley and Spen is a constituency in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament.

The current MP is Kim Leadbeater, a Labour politician, elected in a 2021 by-election by a 323-vote margin. The seat has returned Labour MPs since 1997.

Constit ...

from May 2015 until her murder in June 2016. She was a member of the Labour Party.

Born in Batley

Batley is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees, in West Yorkshire, England. Batley lies south-west of Leeds, north-west of Wakefield and Dewsbury, south-east of Bradford and north-east of Huddersfield. Batley is part of the ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

, Cox studied Social and Political Sciences at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

. Working first as a political assistant, she joined the international humanitarian charity Oxfam

Oxfam is a British-founded confederation of 21 independent charitable organizations focusing on the alleviation of global poverty, founded in 1942 and led by Oxfam International.

History

Founded at 17 Broad Street, Oxford, as the Oxford Co ...

in 2001, where she became head of policy and advocacy at Oxfam GB in 2005. She was selected to contest the Batley and Spen parliamentary seat after the incumbent, Mike Wood, decided not to stand in 2015. She held the seat for Labour with an increased majority. Cox became a campaigner on issues relating to the Syrian civil war, and founded and chaired the all-party parliamentary group Friends of Syria.

On 16 June 2016, Cox died after being shot and stabbed multiple times in the street in the village of Birstall, where she had been due to hold a constituency surgery

A political surgery, constituency surgery, constituency clinic, mobile office or sometimes advice surgery, in British and Irish politics, is a series of one-to-one meetings that a Member of Parliament (MP), Teachta Dála (TD) or other political ...

. Thomas Mair, who held far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

views, was found guilty of her murder in November and sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order.

In July 2021, Cox's sister, Kim Leadbeater, was elected as the Labour MP for Batley and Spen, following a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

.

Early life and career beginnings

Cox was born Helen Joanne Leadbeater on 22 June 1974 inBatley

Batley is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees, in West Yorkshire, England. Batley lies south-west of Leeds, north-west of Wakefield and Dewsbury, south-east of Bradford and north-east of Huddersfield. Batley is part of the ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, to Jean, a school secretary, and Gordon Leadbeater, a toothpaste and hairspray factory worker.

Raised in Heckmondwike, she was educated at Heckmondwike Grammar School

Heckmondwike Grammar School (HGS) is an 11–18 mixed, grammar school and sixth form with academy status in Heckmondwike, West Yorkshire, England.

History

The school was built by Thomas Redfearn and Samuel Wood, who lived on Eldon Street, ...

, a state grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

, where she was head girl. During summers, she worked packing toothpaste. Cox studied at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

, initially studying Archaeology and Anthropology before switching to Social and Political Science, graduating in 1995. She later studied at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 milli ...

.

Following her graduation from Pembroke College, Cox worked as an adviser to Labour MP Joan Walley from 1995 to 1997. She then became head of Key Campaigns at Britain in Europe

Until August 2005, Britain in Europe was the main British pro-European pressure group. Despite connections to Labour and the Liberal Democrats, it was a cross-party organisation with supporters from many different political backgrounds. Initi ...

(1998–99), a pro-European pressure group, before moving to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

to spend two years as an assistant to Glenys Kinnock, wife of former Labour leader

The ''Labour Leader'' was a British socialist newspaper published for almost one hundred years. It was later renamed ''New Leader'' and ''Socialist Leader'', before finally taking the name ''Labour Leader'' again.

19th century

The origins of th ...

Neil Kinnock, who was then a Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

.

From 2001 to 2009, Cox worked for the aid groups Oxfam

Oxfam is a British-founded confederation of 21 independent charitable organizations focusing on the alleviation of global poverty, founded in 1942 and led by Oxfam International.

History

Founded at 17 Broad Street, Oxford, as the Oxford Co ...

and Oxfam International, first in Brussels as the leader of the group's trade reform campaign, then as head of policy and advocacy at Oxfam GB in 2005, and head of Oxfam International's humanitarian campaigns in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 2007. While there, she helped to publish ''For a Safer Tomorrow'', a book authored by Ed Cairns which examines the changing nature of the world's humanitarian policies. Her work for Oxfam, in which she met disadvantaged groups in Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, influenced her political thinking.

Cox's charity work led to a role advising Sarah Brown, wife of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

, who was spearheading a campaign to prevent deaths in pregnancy and childbirth. From 2009 to 2011, Cox was director of the Maternal Mortality Campaign, which was supported by Brown and her husband. The following year, Cox worked for Save the Children

The Save the Children Fund, commonly known as Save the Children, is an international non-governmental organization established in the United Kingdom in 1919 to improve the lives of children through better education, health care, and economic ...

(where she was a strategy consultant), the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, and as director of strategy at the White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood. In 2013, she founded UK Women, a research institute aimed at meeting the needs of women in the UK, where she was also the CEO. Between 2014 and 2015, Cox worked for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), a merging of the William H. Gates Foundation and the Gates Learning Foundation, is an American private foundation founded by Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates. Based in Seattle, Washington, it was ...

.

Cox was the national chair of the Labour Women's Network from 2010 to 2014, and a strategic adviser to the Freedom Fund

The Freedom Fund is an international non-profit organisation dedicated to identifying and investing in the most effective frontline efforts to end slavery. In 2017, the International Labour Organization reported that on any given day in 2016, the ...

, an anti-slavery charity, in 2014. She was also on the board of Burma Campaign UK, a human rights NGO.

Political career

Cox was nominated by the Labour Party to contest theBatley and Spen

Batley and Spen is a constituency in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament.

The current MP is Kim Leadbeater, a Labour politician, elected in a 2021 by-election by a 323-vote margin. The seat has returned Labour MPs since 1997.

Constit ...

seat being vacated by Mike Wood at the 2015 general election. She was selected as its candidate from an all-women shortlist

All-women shortlists (AWS) is an affirmative action practice intended to increase the proportion of female Members of Parliament (MPs) in the United Kingdom, allowing only women to stand in particular constituencies for a particular political p ...

. The Batley and Spen seat was a Conservative marginal

Marginal may refer to:

* ''Marginal'' (album), the third album of the Belgian rock band Dead Man Ray, released in 2001

* ''Marginal'' (manga)

* '' El Marginal'', Argentine TV series

* Marginal seat or marginal constituency or marginal, in polit ...

between 1983 and 1997 but was considered to be a safe seat

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combina ...

for Labour, and Cox won the seat with 43.2% of the vote, increasing Labour's majority to 6,051. Cox made her maiden speech in the House of Commons on 3 June 2015, using it to celebrate her constituency's ethnic diversity, while highlighting the economic challenges facing the community and urging the government to rethink its approach to economic regeneration. She was one of 36 Labour MPs who nominated Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialis ...

as a candidate in the Labour leadership election of 2015, but said she had done so to get him on the list and encourage a broad debate. In the election she voted for Liz Kendall, and announced after the local elections

In many parts of the world, local elections take place to select office-holders in local government, such as mayors and councillors. Elections to positions within a city or town are often known as "municipal elections". Their form and conduct v ...

on 6 May 2016 that she and fellow MP Neil Coyle

Neil Alan John Coyle (born 30 December 1978) is a British Independent politician who has served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Bermondsey and Old Southwark since 2015. He was elected MP as a member of the Labour Party, but was suspende ...

regretted nominating Corbyn.

Cox campaigned for a solution to the Syrian Civil War. In October 2015, she co-authored an article in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'' with Conservative MP Andrew Mitchell, arguing that British military forces could help achieve an ethical solution to the conflict, including the creation of civilian safe havens in Syria. During that month, Cox launched the all-party parliamentary group Friends of Syria, becoming its chair. In the Commons vote in December to approve UK military intervention against ISIL in Syria, Cox abstained because she believed in a more comprehensive strategy that would also include combatting President Bashar al-Assad

Bashar Hafez al-Assad, ', Levantine pronunciation: ; (, born 11 September 1965) is a Syrian politician who is the 19th president of Syria, since 17 July 2000. In addition, he is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and the ...

and his "indiscriminate barrel bombs

A barrel bomb is an improvised unguided bomb, sometimes described as a flying IED (improvised explosive device). They are typically made from a large barrel-shaped metal container that has been filled with high explosives, possibly shrapnel, oil ...

". She wrote: "By refusing to tackle Assad's brutality, we may actively alienate more of the Sunni population, driving them towards Isis. So I have decided to abstain. Because I am not against airstrikes per se, but I cannot actively support them unless they are part of a plan. Because I believe in action to address Isis, but do not believe it will work in isolation."

Andrew Grice of ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'' felt that she "argued forcefully that the UK Government should be doing more both to help the victims and use its influence abroad to bring an end to the Syrian conflict." In February 2016, Cox wrote to the Nobel Committee

A Nobel Committee is a working body responsible for most of the work involved in selecting Nobel Prize laureates. There are five Nobel Committees, one for each Nobel Prize.

Four of these committees (for prizes in physics, chemistry, physio ...

praising the work of the Syrian Civil Defense

The White Helmets ( ''al-Ḫawdh al-bayḍāʾ'' / ''al-Qubaʿāt al-Bayḍāʾ''), officially known as Syria Civil Defence (SCD; ar, الدفاع المدني السوري ''ad-Difāʿ al-Madanī as-Sūrī''), is a volunteer organisation that ...

, a civilian voluntary emergency rescue organisation known as the White Helmets, and nominating them for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

, stating: "In the most dangerous place on earth these unarmed volunteers risk their lives to help anyone in need regardless of religion or politics." The nomination was accepted by the committee, and garnered the support of twenty of her fellow MPs and several celebrities, including George Clooney

George Timothy Clooney (born May 6, 1961) is an American actor and filmmaker. He is the recipient of numerous accolades, including a British Academy Film Award, four Golden Globe Awards, and two Academy Awards, one for his acting and the ot ...

, Daniel Craig, Chris Martin and Michael Palin. The nomination was supported by members of Canada's New Democratic Party

The New Democratic Party (NDP; french: Nouveau Parti démocratique, NPD) is a federal political party in Canada. Widely described as social democratic,The party is widely described as social democratic:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* ...

, who urged Stéphane Dion, the country's Foreign Affairs Minister, to give his backing on behalf of Canada.

Cox, a supporter of the Labour Friends of Palestine & the Middle East, called for the lifting of the blockade of the Gaza Strip

The blockade of the Gaza Strip is the ongoing land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip imposed by Israel and Egypt temporarily in 2005–2006 and permanently from 2007 onwards, following the Israeli disengagement from Gaza.

The bloc ...

. She opposed efforts by the government to curtail the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, and said: "I believe that this is a gross attack on democratic freedoms. Not only is it right to boycott unethical companies but it is our right to do so." Cox was working with Conservative MP Tom Tugendhat

Thomas Georg John Tugendhat, (born 27 June 1973) is a British politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he has served as Minister of State for Security since September 2022. He previously served as Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Comm ...

on a report to be published following the release of the Chilcot Report

The Iraq Inquiry (also referred to as the Chilcot Inquiry after its chairman, Sir John Chilcot)2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including ...

. After her death, Tugendhat wrote in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'': "Our starting point was that while Britain must learn the painful lessons of Iraq, we must not let the pendulum swing towards knee-jerk isolationism, ideological pacifism and doctrinal anti-interventionism." With the charity Tell MAMA she worked on ''The Geography of Anti-Muslim Hatred'', investigating cases of Islamophobia

Islamophobia is the fear of, hatred of, or prejudice against the religion of Islam or Muslims in general, especially when seen as a geopolitical force or a source of terrorism.

The scope and precise definition of the term ''Islamophobia'' ...

; the report was dedicated to her at its launch on 29 June 2016. Two parliamentary questions concerning the Yemeni conflict, tabled by Cox to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

on 14 June, were answered by Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Tobias Ellwood after her death. On 1 July, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'' reported that each answer was accompanied by a government note stating: "This question was tabled before the sad death of the honourable lady but the subject remains important and the government's response ought to be placed on the public record."

Cox was a Remainer in the campaign leading to the 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union. Following her death, the EU referendum campaign was suspended for the day by both sides as a mark of respect. The BBC cancelled editions of '' Question Time'' and '' This Week'', two political discussion programmes scheduled to air that evening focussing on issues relating to the referendum.

Personal life

Cox was married to Brendan Cox from June 2009 until her death in June 2016. He was an adviser oninternational development

International development or global development is a broad concept denoting the idea that societies and countries have differing levels of economic or human development on an international scale. It is the basis for international classificatio ...

to Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

during Brown's premiership, whom she met while she was working for Oxfam. They had two children. The Cox family divided their time between their constituency home and a houseboat

A houseboat is a boat that has been designed or modified to be used primarily as a home. Most houseboats are not motorized as they are usually moored or kept stationary at a fixed point, and often tethered to land to provide utilities. Ho ...

, a converted Dutch barge

A Dutch barge is a traditional flat-bottomed shoal-draught barge, originally used to carry cargo in the shallow ''Zuyder Zee'' and the waterways of Netherlands. There are very many types of Dutch barge, with characteristics determined by region ...

, on the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, moored near Tower Bridge

Tower Bridge is a Grade I listed combined bascule and suspension bridge in London, built between 1886 and 1894, designed by Horace Jones and engineered by John Wolfe Barry with the help of Henry Marc Brunel. It crosses the River Thames clos ...

in London. A secular humanist and trade unionist

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (s ...

, Cox was a supporter of the British Humanist Association and a member of both GMB and Unison.

Murder

At 12:53 pm BST on Thursday, 16 June 2016, Cox was fatally shot and stabbed outside a library in Birstall, West Yorkshire, where she was about to hold a

At 12:53 pm BST on Thursday, 16 June 2016, Cox was fatally shot and stabbed outside a library in Birstall, West Yorkshire, where she was about to hold a constituency surgery

A political surgery, constituency surgery, constituency clinic, mobile office or sometimes advice surgery, in British and Irish politics, is a series of one-to-one meetings that a Member of Parliament (MP), Teachta Dála (TD) or other political ...

at 1:00 pm. According to eyewitnesses, she was shot three times—once near the head—and stabbed multiple times. A 77-year-old local man, Bernard Kenny, was stabbed in the stomach while trying to fend off her attacker. Initial reports indicated that the attacker, Thomas Mair, a 52-year-old Batley and Spen constituent and a white supremacist who was obsessed with Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

s and apartheid-era South Africa and with links to the US-based neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), attack ...

group National Alliance, shouted "Britain first" as he attacked.

The far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

Britain First

Britain First is a far-right, British fascist political party formed in 2011 by former members of the British National Party (BNP). The group was founded by Jim Dowson, an anti-abortion and far-right campaigner.

* ''See also'': The organi ...

party issued a statement denying any involvement or encouragement in the attack and suggested that the phrase "could have been a slogan rather than a reference to our party." Later at Mair's trial, a witness stated that he shouted: "This is for Britain. Britain will always come first."

Four hours after the incident, West Yorkshire Police announced that Cox had died of her injuries shortly after being admitted to Leeds General Infirmary. She was the first sitting MP to be killed since Ian Gow

Ian Reginald Edward Gow (; 11 February 1937 – 30 July 1990) was a British politician and solicitor. As a member of the Conservative Party, he served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Eastbourne from 1974 until his assassination by the P ...

(Conservative), who was killed by a Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish re ...

car bomb in July 1990, and the first MP to be seriously assaulted since Stephen Timms

Sir Stephen Creswell Timms (born 29 July 1955) is a British politician who served as Chief Secretary to the Treasury from 2006 to 2007. A member of the Labour Party, he has been Member of Parliament (MP) for East Ham, formerly Newham North E ...

, who was stabbed by Roshonara Choudhry in an attempted murder in May 2010. A memorial service was held at St Peter's Church St. Peter's Church, Old St. Peter's Church, or other variations may refer to:

* St. Peter's Basilica in Rome

Australia

* St Peter's, Eastern Hill, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

* St Peters Church, St Peters, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

...

in Birstall the following day.

Mair was arrested shortly after the attack. In a statement issued the day after the attack, West Yorkshire Police said that Cox was the victim of a "targeted attack" and the suspect's links to far-right extremism were a "priority line of inquiry" in the search for a motive. Mair was also examined by a psychiatrist who concluded that Mair was responsible for his actions and that poor mental health was not the consequent factor for his attacks. On 18 June, Mair was charged with murder,

Mair was arrested shortly after the attack. In a statement issued the day after the attack, West Yorkshire Police said that Cox was the victim of a "targeted attack" and the suspect's links to far-right extremism were a "priority line of inquiry" in the search for a motive. Mair was also examined by a psychiatrist who concluded that Mair was responsible for his actions and that poor mental health was not the consequent factor for his attacks. On 18 June, Mair was charged with murder, grievous bodily harm

Grievous bodily harm (often abbreviated to GBH) is a term used in English criminal law to describe the severest forms of battery. It refers to two offences that are created by sections 18 and 20 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. The ...

, possession of a firearm with intent to commit an indictable offence

In many common law jurisdictions (e.g. England and Wales, Ireland, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Singapore), an indictable offence is an offence which can only be tried on an indictment after a preliminary hearing ...

and possession of an offensive weapon. He appeared at Westminster Magistrates' Court later that day, and at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

on 20 June.

On 23 November 2016, Mair was found guilty of all charges – the murder of Cox, stabbing Bernard Kenny (a charge of grievous bodily harm with intent), possession of a firearm with intent to commit an indictable offence and possession of an offensive weapon, namely the dagger. The trial judge imposed on Mair (then 53) a life sentence with a whole-life tariff — not to be released from prison, except at the discretion of the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

. As confirmed by the Crown Prosecution Service, Mair’s conviction for a crime amounting to a terrorism offence also means he is officially considered a terrorist by the United Kingdom.

Aftermath

The murder attracted worldwide attention with tributes and memorials for Cox being made with condemnation of Mair. A personal friend, Canadian MPNathan Cullen

Nathan Cullen (born July 13, 1972) is a Canadian politician. A member of the New Democratic Party (NDP), he is the Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Stikine in British Columbia. He has served in the Executive Council of British Columb ...

, paid tribute to Cox in the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada (french: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

The House of Commo ...

. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

Justin Pierre James Trudeau ( , ; born December 25, 1971) is a Canadian politician who is the 23rd and current prime minister of Canada. He has served as the prime minister of Canada since 2015 and as the leader of the Liberal Party since ...

, former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

, the then US Secretary of State John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party, he ...

and former US Representative Gabby Giffords, who was wounded in an assassination attempt in 2011, were among international politicians who sent messages of condemnation and sympathy in the aftermath of her killing. Cox's husband issued a statement urging people to "fight against the hatred that killed her."

Among those who paid tribute to Cox were Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialis ...

, who described her as someone who was "dedicated to getting us to live up to our promises to support the developing world and strengthen human rights", while Prime Minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

said she was "a star for her constituents, a star in parliament, and right across the house." US President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

telephoned Cox's husband to offer his condolences, noting that "the world is a better place because of her selfless service to others." Parliament was recalled on 20 June 2016 for fellow MPs to pay tribute to Cox.

The day after Cox died, 17 June 2016, her husband set up a GoFundMe page named "Jo Cox's Fund" in aid of three charities which he described as "closest to her heart": the Royal Voluntary Service, Hope not Hate, and the White Helmets White Helmets may refer to:

* White Helmets Commission, a body of the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship

* White Helmets (Syrian Civil War), a volunteer organization in Syria and Turkey

** ''The White Helmets'' ...

, a Syrian civil defence group. £700,000 had been raised by 19 June 2016, with the amount exceeding £1 million by the following day. On 20 June, Oxfam

Oxfam is a British-founded confederation of 21 independent charitable organizations focusing on the alleviation of global poverty, founded in 1942 and led by Oxfam International.

History

Founded at 17 Broad Street, Oxford, as the Oxford Co ...

announced it would release '' Stand As One – Live at Glastonbury 2016'', an album of live performances from the festival

A festival is an event ordinarily celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, mela, or eid. A festival c ...

in memory of Cox and that proceeds from the album, released on 11 July, will go towards the charity's work with refugees. The festival opened with a tribute to Cox. On the evening of 23 June, while ballots were being counted in the EU membership referendum, polling officials in the Yorkshire and Humber region observed a minute's silence.

West Yorkshire coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's jur ...

Martin Fleming opened an inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a c ...

into Cox's death at Bradford Coroner's Court on 24 June. It was adjourned following a six-minute hearing and her body released to allow her family to make funeral arrangements. The funeral, "a very small and private family affair", was held in her constituency on 15 July, with many thousands of people paying their respects as the cortege passed.

A by-election in Batley and Spen was held on 20 October 2016. Labour candidate Tracy Brabin, an actress whose credits include a role in ''Coronation Street

''Coronation Street'' is an English soap opera created by Granada Television and shown on ITV since 9 December 1960. The programme centres around a cobbled, terraced street in Weatherfield, a fictional town based on inner-city Salford.

Orig ...

'' in the mid 1990s, won the by-election with 86 percent of the vote. The Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, Liberal Democrats, Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

, and UKIP did not contest the election as a mark of respect. Far-right candidate and former British National Party member Jack Buckby

Jack Buckby (born 10 February 1993) is a British far-right political figure and author who was previously active in a number of groups and campaigns, including the British National Party and Liberty GB. In 2017 he was associated with Anne Marie ...

caused widespread condemnation by standing in the by-election, with Cox's former Labour colleague MP Jack Dromey describing Liberty GB

Liberty Great Britain or Liberty GB was a minor far-right British nationalist political party founded and led by Paul Weston that described itself as "counter-jihad".

Liberty GB was anti-immigration, anti-Islamic and traditionalist. The group's ...

's bid as "obscene, outrageous and contemptible."

One year after her murder, three individuals who came to her aid were honoured in the 2017 Queen's Birthday Honours

The 2017 Queen's Birthday Honours are appointments by some of the 16 Commonwealth realms of Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. The Birthday Honours are awarded as p ...

. Bernard Kenny, a passerby who tried to stop Mair during the attack and was himself stabbed in the stomach, was awarded the George Medal

The George Medal (GM), instituted on 24 September 1940 by King George VI,''British Gallantry Medals'' (Abbott and Tamplin), p. 138 is a decoration of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth, awarded for gallantry, typically by civilians, or in cir ...

, which is given to civilians who exhibit great bravery. PC Craig Nicholls and PC Jonathan Wright of the West Yorkshire Police, who apprehended and arrested her attacker after he had fled the scene, were awarded the Queen's Gallantry Medal

The Queen's Gallantry Medal (QGM) is a United Kingdom decoration awarded for exemplary acts of bravery where the services were not so outstanding as to merit the George Medal, but above the level required for the Queen's Commendation for Braver ...

.

Legacy

In December 2016, a group of politicians came together to record a cover ofthe Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically dr ...

"You Can't Always Get What You Want

"You Can't Always Get What You Want" is a song by the English rock band the Rolling Stones on their 1969 album ''Let It Bleed''. Written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, it was named as the 100th greatest song of all time by '' Rolling Stone' ...

" in honour of Cox. Politicians from the Labour Party, the Conservatives, and the SNP joined with members of the Parliament Choir, the Royal Opera House Thurrock Community Chorus, KT Tunstall

Kate Victoria "KT" Tunstall (born 23 June 1975) is a Scottish singer-songwriter and musician. She first gained attention with a 2004 live solo performance of her song "Black Horse and the Cherry Tree" on '' Later... with Jools Holland''.

The ...

, Steve Harley

Steve Harley (born Stephen Malcolm Ronald Nice; 27 February 1951) is an English singer and songwriter, best known as frontman of the rock group Cockney Rebel, with whom he still tours, albeit with frequent and significant personnel changes.

E ...

, Ricky Wilson, David Gray and other musicians. All profits from sales of the song went to the Jo Cox Foundation. The single raised over £35,000 for the Jo Cox Foundation and was in the iTunes top 10 after its release but was placed 136 in the Christmas chart.

In May 2017, a memorial, designed by Cox's children, was unveiled in the House of Commons. The unveiling took place at the first "Great Get Together" event that the Jo Cox Foundation held and was in the form of a family day at Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. In June 2017, Cox's husband Brendan published ''Jo Cox: More In Common'', a book that talks about the impact of his wife's death on their family. Also in June 2017, and to mark the first anniversary of Cox's death, her family and friends urged people to take part in a weekend of events to celebrate her life and held under the banner of "The Great Get Together"; events included picnics, street parties and concerts.

A street, formerly the after Pierre-Étienne Flandin, in Avallon, a town in the Yonne ' of France, was renamed the in May 2017. In

A street, formerly the after Pierre-Étienne Flandin, in Avallon, a town in the Yonne ' of France, was renamed the in May 2017. In Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, a square beside the Ancienne Belgique concert hall was renamed the / in September 2018.

A work of contemporary dance theatre inspired by Cox's political and social beliefs, entitled "More in Common", was created by Youth Music Theatre UK in August 2017 and presented at the Square Chapel

The Square Chapel in Halifax, West Yorkshire, England, was designed by Thomas Bradley and James Kershaw at the instigation of Titus Knight, a local preacher. Construction started in 1772 and the chapel was visited by John Wesley in July of tha ...

, Halifax.

Her alma mater, Pembroke College, announced a Jo Cox Studentship in Refugee and Migration Studies, which was first awarded in 2017 after extensive fundraising by members of the college.

Following the approval by the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

on the Withdrawal Agreement

The Brexit withdrawal agreement, officially titled Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, is a treaty between the European Un ...

on 29 January 2020, European Parliament President David Sassoli ended his address by referencing Jo Cox's quote "More in Common".

Out of respect for Cox, the 2016 Batley and Spen by-election had seen parties with parliamentary representation not stand against Labour candidate Tracy Brabin who was elected with an 85.8% majority. In May 2021, Brabin was elected as Mayor of West Yorkshire and, consequently, resigned as MP. On 2 July 2021, Jo Cox's sister Kim Leadbeater, who declared that she had not previously been a political person but 'cared deeply' about where she had been born and grew up, was elected in the 2021 Batley and Spen by-election

A by-election was held in the UK parliamentary constituency of Batley and Spen on 1 July 2021, following the resignation of the previous Member of Parliament (MP) Tracy Brabin, who was elected Mayor of West Yorkshire on 10 May. Under the devolu ...

.

Coat of arms

On 24 June 2017, acoat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

, designed with the input of Cox's children, was unveiled by her family at the House of Commons, where MPs killed in office are honoured with heraldic shields. The elements of the arms included four roses, to symbolise the members of Cox's family (two white roses, for Yorkshire, and two red, for Labour); and the tincture

A tincture is typically an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol (ethyl alcohol). Solvent concentrations of 25–60% are common, but may run as high as 90%.Groot Handboek Geneeskrachtige Planten by Geert Verhelst In chemistr ...

s green, purple, and white, which were the colours of the British suffragette movement. The motto, "More in Common", is displayed below the shield, and comes from her maiden speech made in Parliament, in which she said: "We are far more united and have far more in common than that which divides us."

See also

*List of serving British MPs who were assassinated

This is a list of sitting members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom ( MPs) who died by assassination or other culpable homicide.

Spencer Perceval is the only British prime minister to have been assassinated, having been shot on 1 ...

*Stephen Timms

Sir Stephen Creswell Timms (born 29 July 1955) is a British politician who served as Chief Secretary to the Treasury from 2006 to 2007. A member of the Labour Party, he has been Member of Parliament (MP) for East Ham, formerly Newham North E ...

– MP injured in 2010 after being stabbed by Islamist Roshonara Choudhry

* Nigel Jones, Baron Jones of Cheltenham – MP who was wounded in a 2000 sword attack at his advice surgery by a constituent he had previously tried to help (his aide Andrew Pennington

Andrew James Pennington (1 February 1960 – 28 January 2000) was a British Liberal Democrat politician and a posthumous recipient of the George Medal in 2001. He was a Gloucestershire County Councillor from 1985 until his death in a stabbing ...

was killed)

* David Amess – MP who was fatally stabbed in 2021 while holding a constituency surgery.Jo Cox Foundation

a charity established in memory of Jo Cox.

References

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cox, Jo 1974 births 2016 deaths Assassinated English politicians English humanists English murder victims Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Alumni of the London School of Economics People from Batley Deaths by firearm in England Deaths by stabbing in England Female members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Oxfam people People educated at Heckmondwike Grammar School People murdered in England UK MPs 2015–2017 Assassinated British MPs English terrorism victims Terrorism deaths in England 21st-century British women politicians Violence against women in England