Jimmie H. Davis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Houston Davis (September 11, 1899 – November 5, 2000) was an American politician, singer and songwriter of both sacred and popular songs. Davis was elected for two nonconsecutive terms from 1944 to 1948 and from 1960 to 1964 as the

Davis was elected in 1938 as Shreveport's public safety commissioner. At the time, Shreveport had the

Davis was elected in 1938 as Shreveport's public safety commissioner. At the time, Shreveport had the

Amistad Research Center, Tulane University; Sources: Adam Fairclough. ''Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972''. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1995. It was modeled after Mississippi's commission, established in 1956 to resist integration. Davis tapped Frank Voelker Jr., City Attorney of Lake Providence, to chair the newly established Commission. It was given unusual powers to investigate state citizens, and used its authority to exert economic pressure to suppress civil rights activists. Voelker left the commission in 1963 to run for governor but placed poorly in the primary; he withdrew and supported other candidates. In his second term, Davis chose veteran Representative

State of Louisiana Biography

Cemetery Memorial

by La-Cemeteries

Listen to Jimmie singing "She's a Real Hum Dinger"

Jimmie Davis recordings

at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

an

at

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of his native Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. As Governor, Davis was an opponent of efforts to desegregate

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

Louisiana.

Davis was a nationally popular country music

Country (also called country and western) is a genre of popular music that originated in the Southern and Southwestern United States in the early 1920s. It primarily derives from blues, church music such as Southern gospel and spirituals, ...

and gospel singer

Gospel music is a traditional genre of Christian music, and a cornerstone of Christian media. The creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of gospel music varies according to culture and social context. Gospel music is com ...

from the 1930s into the 1960s, occasionally recording and performing as late as the early 1990s. He appeared as himself in a number of Hollywood movies. He was inducted into six halls of fame, including the Country Music Hall of Fame

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Tennessee, is one of the world's largest museums and research centers dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of American vernacular music. Chartered in 1964, the museum has amas ...

, the Southern Gospel Music Association

The Southern Gospel Music Association (''SGMA'') is a non-profit corporation formed as an association of southern gospel music singers, songwriters, fans, and industry workers. Membership is acquired and maintained through payment of annual dues. T ...

Hall of Fame, and the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame

The Louisiana Music Hall of Fame (LMHOF) is a non-profit hall of fame based in Baton Rouge, the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana, that seeks to honor and preserve the state's music culture and heritage and to promote education about the state ...

. At the time of his death in 2000, he was the oldest living former governor as well as the last living governor to have been born in the 19th century.

Early life and career

Childhood and birth date confusion

Davis was born to asharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

couple, the former Sarah Elizabeth Works (1877–1965) and Samuel Jones Davis (1873–1945), in Beech Springs, southeast of Quitman in Jackson Parish

Jackson Parish (French: ''Paroisse de Jackson'') is a parish in the northern part of the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 15,031. The parish seat is Jonesboro. The parish was formed in 1845 from parts of Clai ...

, north Louisiana. It is now a ghost town. The family was so poor that young Jimmie did not have a bed in which to sleep until he was nine years old.

Davis was not sure of his date of birth; according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', "Various newspaper and magazine articles over the last 70 years said he was born in 1899, 1901, 1902 or 1903. He told The New York Times several years ago that his sharecropper parents could never recall just when he was born – he was, after all, one of 11 children – and that he had not had the slightest idea when it really was." The birth date listed on his Country Music Hall of Fame plaque is September 11, 1902. The 1900 US Census recorded his birth as September 1899, which his parents would have told the census taker.

Education

Davis graduated from Beech Springs High School and fromSoule Business College

Soule Business College (sometimes called Soulé's Business College, Soule Commercial College, or Soule College) was an educational institution focused primary on practical business skills, established by George Soule in New Orleans, Louisiana in ...

, in . Davis received his bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

in history from the Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

-affiliated Louisiana College

Louisiana Christian University (LCU) is a private Baptist university in Pineville, Louisiana. It enrolls 1,100 to 1,200 students. It is affiliated with the Louisiana Baptist Convention (Southern Baptist Convention).

Louisiana Christ ...

in Pineville in Rapides Parish

Rapides Parish () (french: Paroisse des Rapides) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 131,613. The parish seat is Alexandria, which developed along the Red River of the South. ''Rapides ...

. He received a master's degree from Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

in Baton Rouge.

His 1927 master's thesis, which examines the intelligence levels of different races, is titled ''Comparative Intelligence of Whites, Blacks and Mulattoes.''

Career beginnings

During the late 1920s, Davis taught history (and, unofficially,yodeling

Yodeling (also jodeling) is a form of singing which involves repeated and rapid changes of pitch between the low-pitch chest register (or "chest voice") and the high-pitch head register or falsetto. The English word ''yodel'' is derived from the ...

) for a year at the former Dodd College for Girls in Shreveport. The college president, Monroe E. Dodd, who was also the pastor of First Baptist Church of Shreveport and a radio preacher, invited Davis to serve on the faculty.

Musical career

Davis became a commercially successful singer of rural music before he entered politics. His early work was in the style of country music singerJimmie Rodgers

James Charles Rodgers (September 8, 1897 – May 26, 1933) was an American singer-songwriter and musician who rose to popularity in the late 1920s. Widely regarded as "the Father of Country Music", he is best known for his distinctive rhythmi ...

. Davis was also known for recording energetic and raunchy blues tunes, such as "Red Nightgown Blues" and "Tom Cat and Pussy Blues". Some of these records included slide guitar accompaniment by black bluesman Oscar "Buddy" Woods

Oscar "Buddy" Woods (born c. 1900 or c.1903, died December 14, 1955) was an American Texas blues guitarist, singer and songwriter.

Woods, who was an early blues pioneer in lap steel, slide guitar playing, recorded thirty-five tracks between 19 ...

. During his first run for governor, opponents reprinted the lyrics of some of these songs in order to undermine Davis's campaign. In one case, anti-Davis forces played some records over an outdoor sound system, only to give up after the crowds started dancing, ignoring the double-entendre lyrics. Until the end of his life, Davis never denied or repudiated those records.

In 1999, "You Are My Sunshine

"You Are My Sunshine" is a song published by Jimmie Davis and Charles Mitchell on January 30, 1940. According to Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), the song has been recorded by over 350 artists and translated into 30 languages.

In 1977, the Louisi ...

" was honored with a Grammy Hall of Fame Award

The Grammy Hall of Fame is a hall of fame to honor musical recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance. Inductees are selected annually by a special member committee of eminent and knowledgeable professionals from all branches of ...

, and the Recording Industry Association of America named it one of the Songs of the Century

The "Songs of the Century" list is part of an education project by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the National Endowment for the Arts, and Scholastic Inc. that aims to "promote a better understanding of America's musical and ...

. "You Are My Sunshine" was ranked in 2003 as No. 73 on ''CMT's 100 Greatest Songs in Country Music''. Until his death, Davis insisted that he wrote the song. Virginia Shehee, a Shreveport businesswoman, philanthropist, and state senator, introduced legislation to designate "You Are My Sunshine" as the official state song. The song was reportedly written for Elizabeth Selby, a resident of Urbana, Illinois

Urbana ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Champaign County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2020 census, Urbana had a population of 38,336. As of the 2010 United States Census, Urbana is the 38th-most populous municipality in Illinois. It ...

and housemother of Wescoga ("Wesley Co-Op for Gals") at the time the song was written.

Davis often performed during his campaign stops when running for governor of Louisiana. After being elected in 1944, he became known as the "singing governor." While governor, he had a No. 1 hit single in 1945 with "There's a New Moon Over My Shoulder

"There's a New Moon Over My Shoulder" is a 1944 song written by Jimmie Davis, Ekko Whelan, and Lee Blastic and made popular by Tex Ritter. The song was the B-side to Tex Ritter's, "I'm Wastin' My Tears on You". "There's a New Moon Over My Shoul ...

". Davis recorded for the Victor Talking Machine Company

The Victor Talking Machine Company was an American recording company and phonograph manufacturer that operated independently from 1901 until 1929, when it was acquired by the Radio Corporation of America and subsequently operated as a subsidi ...

, and Decca Records for decades and released more than 40 albums.

A long-time Southern Baptist, Davis recorded a number of Southern gospel albums. In 1967 he served as president of the Gospel Music Association

The Gospel Music Association (GMA) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1964 for the purpose of supporting and promoting the development of all forms of gospel music. As of 2011, there are about 4,000 members worldwide. The GMA's membership co ...

. He was a close friend of the North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

-born band leader Lawrence Welk

Lawrence Welk (March 11, 1903 – May 17, 1992) was an American accordionist, bandleader, and television impresario, who hosted the '' The Lawrence Welk Show'' from 1951 to 1982. His style came to be known as "champagne music" to his radio, te ...

, who frequently reminded viewers of his television program of his association with Davis.

A number of his songs were used as part of motion picture soundtracks. Davis appeared in half a dozen films, including one starring Ozzie and Harriet

''The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet'' is an American television sitcom that aired on ABC from October 3, 1952, to April 23, 1966, and starred the real-life Nelson family. After a long run on radio, the show was brought to television, where it ...

, who had a TV series under their names. Members of Davis's last band included Allen "Puddler" Harris of Lake Charles. He had served as pianist for singer Ricky Nelson

Eric Hilliard Nelson (May 8, 1940 – December 31, 1985) was an American musician, songwriter and actor. From age eight he starred alongside his family in the radio and television series ''The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet''. In 1957, he bega ...

early in his career.

Davis was also a close acquaintance of the country singer-songwriter Hank Williams, with whom he co-wrote the top-10 hit "(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle

"(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle" is a song written by Hank Williams and Jimmie Davis. It became his fourteenth consecutive Top 10 single in 1951.

Background

Hank Williams was a Jimmie Davis disciple, who scored big hits on Decca Records ...

" in 1951, supposedly on a fishing day they spent together.

Singles

Political career

Davis was elected in 1938 as Shreveport's public safety commissioner. At the time, Shreveport had the

Davis was elected in 1938 as Shreveport's public safety commissioner. At the time, Shreveport had the city commission

City commission government is a form of local government in the United States. In a city commission government, voters elect a small commission, typically of five to seven members, typically on a plurality-at-large voting basis.

These commissione ...

form of government. After four years in Shreveport City Hall, Davis was elected in 1942 to the Louisiana Public Service Commission

The Louisiana Public Service Commission (LPSC) is an independent regulatory agency which manages public utilities and motor carriers in Louisiana. The commission has five elected members chosen in single-member districts for staggered six-year te ...

. The rate-making body meets in the capital, Baton Rouge. He was elected during his term as governor and left after two years.

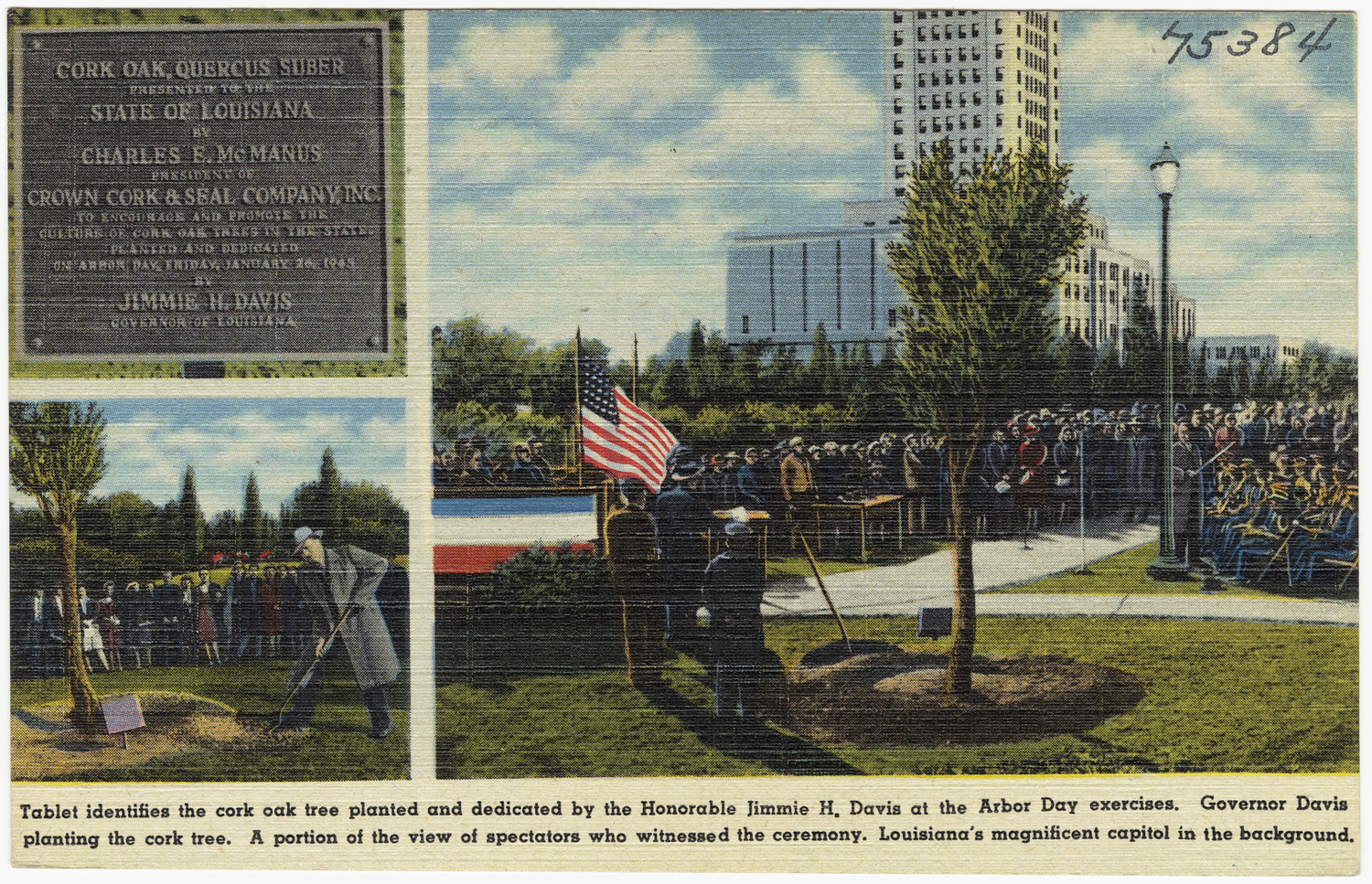

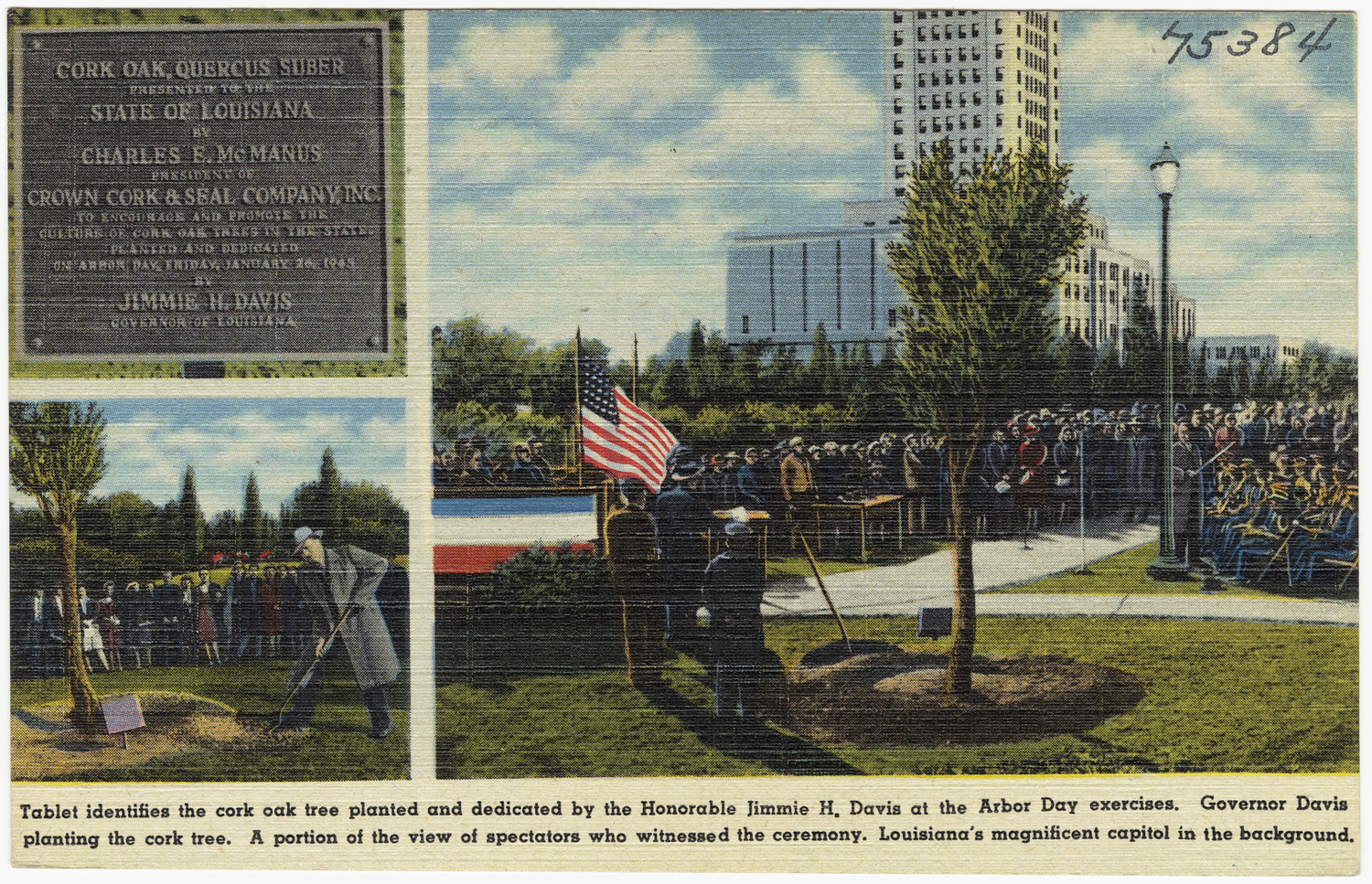

First term as governor (1944–1948)

Davis was elected governor as a Democrat in 1944. Among those eliminated in the primary were State SenatorErnest S. Clements

Ernest is a given name derived from Germanic word ''ernst'', meaning "serious". Notable people and fictional characters with the name include:

People

* Archduke Ernest of Austria (1553–1595), son of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor

* Ernest, ...

of Oberlin in Allen Parish

Allen Parish (french: Paroisse d'Allen) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 25,764. The parish seat is Oberlin and the largest city is Oakdale. Allen Parish is in southwestern Louisia ...

, freshman U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

James H. Morrison of Hammond in Tangipahoa Parish

Tangipahoa Parish (; French: ''Paroisse de Tangipahoa'') is a parish located in the southeast corner of the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 121,097. The parish seat is Amite City, while the largest city is ...

, and Sam Caldwell

Samuel Shepherd Caldwell (November 4, 1892 – August 14, 1953), was a Louisiana oilman and politician who served as mayor of Shreveport, Louisiana, from 1934 to 1946.

Caldwell was an unusually staunch segregationist even for the era in the ...

, the mayor of Shreveport. Davis and Caldwell had served together earlier in Shreveport municipal government.

In the runoff

Runoff, run-off or RUNOFF may refer to:

* RUNOFF, the first computer text-formatting program

* Runoff or run-off, another name for bleed, printing that lies beyond the edges to which a printed sheet is trimmed

* Runoff or run-off, a stock marke ...

, Davis defeated Lewis L. Morgan, an elderly attorney and former U.S. representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

from Covington, the seat of St. Tammany Parish, who had been backed by former Governor Earl Kemp Long

Earl Kemp Long (August 26, 1895 – September 5, 1960) was an American politician and the 45th governor of Louisiana, serving three nonconsecutive terms. Long, known as "Uncle Earl", connected with voters through his folksy demeanor and c ...

and New Orleans Mayor Robert Maestri

Robert Sidney Maestri (December 11, 1899 – May 6, 1974) was mayor of New Orleans from 1936 to 1946 and a key ally of Huey P. Long Jr. and Earl Kemp Long.

Early life

Robert Maestri was born in New Orleans on December 11, 1899, the son of, ...

. In the runoff, Davis received 251,228 (53.6 percent) to Morgan's 217,915 (46.4 percent).

Davis recruited Chris Faser Jr., a young staff member of the Public Service Commission, to manage his gubernatorial race and act as his chief of staff. Faser became the "go-to" guy to obtain access to the governor.

Davis pleased white liberals with his appointments to high positions of two of the leaders of the impeachment effort against Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "the Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination ...

. He named Cecil Morgan

Cecil Morgan Sr. (August 20, 1898 – June 14, 1999) was an American politician in the state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the Unite ...

of Shreveport to the Louisiana Civil Service Commission. Morgan was succeeded in the Louisiana House by Rupert Peyton of Shreveport, who also served as an aide to Davis. In addition, Davis retained the anti-Long Ralph Norman Bauer of St. Mary Parish as House speaker, a selection made originally in 1940 by Sam Jones.

Davis reached out to the Longites when he commuted the prison sentence imposed on former LSU President James Monroe Smith James Monroe Smith may refer to:

* James Monroe Smith (Georgia planter) (1839–1915), planter and state legislator in Georgia

* James Monroe Smith (academic administrator) James Monroe Smith (October 9, 1888 – June 6, 1949) was an American educa ...

, convicted in the Louisiana Hayride scandals

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

of the late 1930s. Like Davis, Smith was a native of Jackson Parish.

Earl Long was seeking the lieutenant governorship on the Lewis Morgan "ticket" and led in the first primary in 1944, but he lost the runoff to J. Emile Verret of New Iberia

New Iberia (french: La Nouvelle-Ibérie; es, Nueva Iberia) is the largest city in and parish seat of Iberia Parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The city of New Iberia is located approximately southeast of Lafayette, and forms part of the Laf ...

, then the president of the Iberia Parish School Board

Iberia Parish School System is a school district headquartered in New Iberia, Louisiana, United States. The district serves all of Iberia Parish and all of the city of Delcambre, which has portions located in Vermilion Parish.

School uniforms

B ...

.

Davis kept his hand in show business, and set a record for absenteeism during his first term. He made numerous trips to Hollywood to make Western "horse operas

A horse opera, hoss opera, oat opera or oater is a Western movie or television series that is clichéd or formulaic, in the manner of a soap opera.

The term, which was originally coined by silent film-era Western star William S. Hart, is used va ...

."

Under the term limit

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

provision of the state constitution then in effect, Davis was limited to a single non-consecutive term in office.

The election of 1959–1960

When he became a candidate for a second term in 1959–60, Davis had been out of office for nearly a dozen years. In a later study of this election, three Louisiana State Universitypolitical scientist

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

s described him by the following:

Davis has all the external attributes of a "man of the people", but his serious political connections seem to be with the arish-seatelite and its allies, particularly the major industrial combinations of the state. He is in many respects a toned-down version of the old-style southern politician who could spellbound the mass of voters into supporting him regardless of the effects of his programs on their welfare. ... Davis creates the perfect image of a man to be trusted and one whose intense calm is calculated to bring rational balance into the political life of the state.Davis was running at a time when African Americans in the civil rights movement were seeking social justice and restoration of their constitutional rights. In 1954 the US Supreme Court had ruled in ''

Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional and urged states to integrate their facilities. With a pledge to fight for continued segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

in public education, Davis won the Democratic gubernatorial

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

nomination over a crowded field.

It included fellow segregationist State Senator William M. Rainach of Claiborne Parish, former Lieutenant Governor Bill Dodd

William Joseph Dodd (November 25, 1909 – November 16, 1991) was an American politician who held five positions in the Louisiana state government in the mid-20th century, including state representative, lieutenant governor, state auditor, pre ...

of Baton Rouge, former Governor James A. Noe of Monroe, and New Orleans Mayor deLesseps Story Morrison

deLesseps Story Morrison Sr., also known as Chep Morrison (January 18, 1912 – May 22, 1964), was an American attorney and politician who was the 54th mayor of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1946 to 1961. He then served as an appointee of U.S. ...

. Addison Roswell Thompson

Addison may refer to:

Places Canada

* Addison, Ontario

United States

* Addison, Alabama

*Addison, Illinois

*Addison Street in Chicago, Illinois which runs by Wrigley Field

* Addison, Kentucky

*Addison, Maine

*Addison, Michigan

*Addison, New York ...

, the operator of a New Orleans taxicab

A taxi, also known as a taxicab or simply a cab, is a type of vehicle for hire with a driver, used by a single passenger or small group of passengers, often for a non-shared ride. A taxicab conveys passengers between locations of their choi ...

stand and a member of the Ku Klux Klan, also filed candidacy papers.

Davis ran second in the primary to "Chep" Morrison, considered an anti-Long liberal by Louisiana standards. He defeated Morrison in the party runoff held on January 9, 1960. As African Americans (who had supported the Republican Party after the Civil War) were still largely disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

in Louisiana, the Democratic primary was the only competitive race for office in the one-party state.

In the first round of balloting, Davis polled 213,551 (25.3 percent) to Morrison's 278,956 (33.1 percent). Rainach ran third with 143,095 (17 percent). Noe finished fourth with 97,654 (11.6 percent), and Dodd followed with 85,436 (10.1 percent). Davis won the northern and central parts of the state plus Baton Rouge, while Morrison dominated the southern portion of the state, particularly the French cultural parishes. In the runoff, Davis prevailed, 487,681 (54.1 percent) to Morrison's 414,110 (45.5 percent). It was estimated that Davis drew virtually all the Rainach support from the first primary.

Earl Long endorsed Davis in the runoff in part because he had a longstanding personal dislike of Morrison. Long's gubernatorial running-mate, James A. Noe, who finished fourth in the primary, stood with Morrison, as did the fifth-place gubernatorial candidate and former Long lieutenant governor, Bill Dodd.

Rainach and his unsuccessful candidate for state comptroller, later U.S. Representative Joe D. Waggonner, both endorsed Davis on the premise that Davis would be a stronger segregationist than Morrison. Davis had avoided segregationist rhetoric in the first primary race in 1959. According to Morrison, the singer had sought support from the NAACP in New Orleans and Lake Charles.

In the runoff with Morrison, Davis tried to identify as a more determined and dedicated segregationist than his rival. Morrison questioned Davis's change in campaign strategy and also appealed to segregationists. Morrison charged that Davis had "operated an integrated honky-tonk

A honky-tonk (also called honkatonk, honkey-tonk, or tonk) is both a bar that provides country music for the entertainment of its patrons and the style of music played in such establishments. It can also refer to the type of piano (tack piano) ...

in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

", when Davis was out of state with his singing career. Morrison also said that Davis had allowed the illegal operation of nine thousand slot machine

A slot machine (American English), fruit machine (British English) or poker machine (Australian English and New Zealand English) is a gambling machine that creates a game of chance for its customers. Slot machines are also known pejoratively a ...

s when Davis was governor during the 1940s.

Meanwhile, Earl Long had run unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor in the first primary in 1959. There was a runoff between Morrison's choice for the job, Alexandria Mayor W. George Bowdon Jr., and Davis's selection, former state House Speaker Clarence C. "Taddy" Aycock of Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People

* Franklin (given name)

* Franklin (surname)

* Franklin (class), a member of a historical English social class

Places Australia

* Franklin, Tasmania, a township

* Division of Franklin, federal electoral d ...

, St. Mary Parish. Aycock defeated Bowdon by a margin similar to the plurality of Davis over Morrison. The defeat was Long's second for lieutenant governor. He had lost in the 1944 primary to J. Emile Verret of Iberia Parish

Iberia Parish (french: Paroisse de l'Ibérie, es, Parroquia de Iberia) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2020 census, it had a population of 69,929; the parish seat is New Iberia.

The parish was formed in 1868 during ...

, who served in the second-ranking position in the first Davis administration.

Davis effectively used the slogan "He's One of Us" in the gubernatorial race. Number 6 on the ballot, he assembled an intraparty ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

for other statewide constitutional officers, including Aycock for lieutenant governor, Roy R. Theriot of Abbeville

Abbeville (, vls, Abbekerke, pcd, Advile) is a commune in the Somme department and in Hauts-de-France region in northern France.

It is the chef-lieu of one of the arrondissements of Somme. Located on the river Somme, it was the capital of ...

for comptroller, Douglas Fowler of Coushatta

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the terri ...

for custodian of voting machines, Jack P. F. Gremillion

Jack Paul Faustin Gremillion, Sr. (June 15, 1914 – March 2, 2001), was the Democratic Attorney General of Louisiana from 1956 to 1972. He was widely known for his political partnership with Governor Earl Long, his opposition to desegregatio ...

for attorney general, Dave L. Pearce, originally from West Carroll Parish, for agriculture commissioner, Ellen Bryan Moore for register of state lands, and Rufus D. Hayes

Rufus is a masculine given name, a surname, an Ancient Roman cognomen and a nickname (from Latin ''rufus'', "red"). Notable people with the name include:

Given name

Politicians

* Rufus Ada George (born 1940), Nigerian politician

* Rufus A ...

for insurance commissioner; the latter four were all based in Baton Rouge. The entire Davis ticket was elected.

In their study ''The Louisiana Election of 1960'', William C. Havard, Rudolf Heberle, and Perry H. Howard

Perry, also known as pear cider, is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears, traditionally the perry pear. It has been common for centuries in England, particularly in Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire. It is also mad ...

demonstrated that Davis built his second-primary victory by narrowly edging Morrison in the eastern and western extremities of south Louisiana. Davis secured the backing of organized labor and made inroads among the white, urban working class, which would have been essential to a Morrison victory. In the seven urban industrial parishes, which then comprised some 46.5 percent of the total turnout, Davis topped Morrison by 7,368 votes (50.8 percent) of the 419,537 applicable subtotal.

Morrison polled 60 percent in his own Orleans Parish and 54.6 percent in adjacent suburban Jefferson Parish Jefferson may refer to:

Names

* Jefferson (surname)

* Jefferson (given name)

People

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third president of the United States

* Jefferson (footballer, born 1970), full name Jefferson Tomaz de Souza, Brazilian foo ...

, but in the industrial strip and in more Protestant areas, Morrison slipped. The second primary attracted 57,744 more votes than the initial stage of balloting, and analysts found that the lion's share of additional ballots were filed by segregationists who backed Davis.

In the general election held on April 19, 1960, Davis defeated Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Francis Grevemberg

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

* Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural ...

, a Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

native, by a margin of nearly 82–17 percent. Grevemberg had been head of the state police under Democratic Governor Robert F. Kennon and had gained a reputation for fighting organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

. He called for a true two-party system for Louisiana. As the Democratic nominee in the nearly one-party state, Davis faced no serious political threat and did little campaigning against Grevemberg.

It has been reported that had General Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American Air Force general who implemented a controversial strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. He later served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air ...

turned down George C. Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

's offer to be his candidate for vice president in 1968 on the American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in t ...

ticket, that Wallace was ready to announce Davis as his selection for vice president. Other sources say Wallace's second choice was the former governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus

Orval Eugene Faubus ( ; January 7, 1910 – December 14, 1994) was an American politician who served as the 36th Governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967, as a member of the Democratic Party.

In 1957, he refused to comply with a unanimous ...

.

Davis and Dodd

In the 1959 campaign, Bill Dodd had attacked Davis ferociously: it was part of Dodd's strategy to get Davis to withdraw from the primary. "Nothing personal in his odd'sheart, just a cold-blooded plan to wind up in a second primary against Morrison, who he figured could not win against anyonelse LSE may refer to:

Computing

* LSE (programming language), a computer programming language

* LSE, Latent sector error, a media assessment measure related to the hard disk drive storage technology

* Language-Sensitive Editor, a text editor used ...

in a runoff," said Davis in the introduction to Dodd's memoirs, ''Peapatch Politics: The Earl Long Era in Louisiana Politics''.

Dodd endorsed Morrison in the runoff, but he had a long-term reason for this decision. Dodd planned to run for school superintendent in the 1963 primary, and he wanted to have at least the neutrality of Morrison four years thereafter.

Dodd and Davis later became close friends. In Davis' words:

Bill and I have many things in common. We share the same type of religion and boyhood background; we got our start as schoolteachers and figured prominently in public education; we both served in public life at or near the top. And I like to feel that we share a common appreciation and respect for people, all people. One of the greatest rewards in politics is meeting people. And one of the greatest and most unusual men I've ever met is Bill Dodd.

Second term (1960–1964)

Davis' appointees in the second term included outgoing State RepresentativeClaude Kirkpatrick Claude may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People and fictional characters

* Claude (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Claude (surname), a list of people

* Claude Lorrain (c. 1600–1682), French landscape painter, draughtsman and etch ...

of Jennings

Jennings is a surname of early medieval English origin (also the Anglicised version of the Irish surnames Mac Sheóinín or MacJonin). Notable people with the surname include:

*Jennings (Swedish noble family)

A–G

*Adam Jennings (born 1982), A ...

, who was named to succeed Lorris M. Wimberly as the Director of Public Works. In that capacity, Kirkpatrick took the steps for a joint agreement with Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

to establish the popular Toledo Bend Reservoir

Toledo Bend Reservoir is a reservoir on the Sabine River between Texas and Louisiana. The lake has an area of 185,000 acres (749 km2), the largest man-made body of water partially in both Louisiana and Texas, the largest in the South, and ...

, a haven for boating and fishing. Mrs. Kirkpatrick, the former Edith Killgore, a native of Claiborne Parish, headed Davis' women's campaign division for southwestern Louisiana. He appointed Alexandria businessman Morgan W. Walker Sr. to the State Mineral Board. Walker founded a company which later became part of Continental Trailways

The Trailways Transportation System is an American network of approximately 70 independent bus companies that have entered into a brand licensing agreement. The company is headquartered in Fairfax, Virginia.

History

The predecessor to Trailwa ...

Bus

A bus (contracted from omnibus, with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but is also in use for cha ...

lines. Davis named as state highway director Ray Burgess of Baton Rouge, who considered running for governor in the 1963 primary.

As part of his support of segregation, Davis initiated passage of state legislation to create the Louisiana State Sovereignty Commission

The Louisiana State Sovereignty Commission was a government agency of the Louisiana state government established to combat desegregation, which operated from June 1960 to 1967 in the capitol city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The group warned of "cre ...

, which operated from 1960 to 1967. It "espoused states rights, anti-communist and segregationist ideas, with a particular focus on maintaining the status quo in race relations. It was closely allied with the Louisiana Joint Legislative Committee on Un-American Activities.""Louisiana State Sovereignty Commission"Amistad Research Center, Tulane University; Sources: Adam Fairclough. ''Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972''. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1995. It was modeled after Mississippi's commission, established in 1956 to resist integration. Davis tapped Frank Voelker Jr., City Attorney of Lake Providence, to chair the newly established Commission. It was given unusual powers to investigate state citizens, and used its authority to exert economic pressure to suppress civil rights activists. Voelker left the commission in 1963 to run for governor but placed poorly in the primary; he withdrew and supported other candidates. In his second term, Davis chose veteran Representative

J. Thomas Jewell

''J. The Jewish News of Northern California'', formerly known as ''Jweekly'', is a weekly print newspaper in Northern California, with its online edition updated daily. It is owned and operated by San Francisco Jewish Community Publications In ...

of New Roads

New Roads (historically french: Poste-de-Pointe-Coupée) is a city in and the parish seat of Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, United States. The center of population of Louisiana was located in New Roads in 2000. The population was 4,831 at the ...

in Pointe Coupee Parish

Pointe Coupee Parish ( or ; french: Paroisse de la Pointe-Coupée) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,802; in 2020, its population was 20,758. The parish seat is New Roads.

Pointe ...

as House Speaker to succeed Bob Angelle

Bob, BOB, or B.O.B. may refer to:

Places

*Mount Bob, New York, United States

* Bob Island, Palmer Archipelago, Antarctica

People, fictional characters, and named animals

*Bob (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Bob (surnam ...

. Davis secured passage of a $60 million public improvements bond issue through the State Board and Building Commission, an organization controlled by the governor. He gained legislative support from many formerly pro-Long lawmakers and cemented his hold on the traditional anti-Long bloc. He avoided defeat on any legislation that he strongly supported and was able to defeat nearly all bills with which he did not concur.

He offered tacit support to Presidents John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, national Democrats, to secure the state's hold of pending offshore oil revenues. In the 1963 legislative fiscal session, he defeated efforts to procure an unpledged presidential elector slate for the 1964 general election, by which time he had been succeeded by John J. McKeithen.

Fourth place in 1971

In 1971, Davis entered another crowded Democraticgubernatorial

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

primary field with new political prospects, but he finished in fourth place with 138,756 ballots (11.8 percent).

In a runoff election held in December 1971, U.S. Representative Edwin Washington Edwards of Crowley

Crowley may refer to:

Places

* Crowley, Mendocino County, California, an unincorporated community

*Crowley County, Colorado

* Crowley, Colorado, a town in Crowley County

*Crowley, Louisiana, a city

* Crowley, Oregon (disambiguation)

* Crowley, Te ...

, Acadia Parish

Acadia Parish (french: link=no, Paroisse de l'Acadie) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 57,576. The parish seat is Crowley. The parish was founded from parts of St. Landry Parish in ...

, defeated then state Senator J. Bennett Johnston Jr., of Shreveport for the party nomination. That vote was close: Edwards, 584,262 (50.2 percent) to Johnston's 579,774 (49.8 percent). Edwards beat Republican David C. Treen

David Conner Treen Sr. (July 16, 1928 – October 29, 2009) was an American politician and attorney at law (United States), attorney from Louisiana. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Treen served as United State ...

in the state general election held on February 1, 1972. By that time, Davis' days as a politician were clearly behind him.

Toward the end of his life, longtime Democrat Davis endorsed at least two Republican candidates after the state's voters had gone through a political realignment. In 1996 Davis endorsed Republican state representative Woody Jenkins

Louis Elwood Jenkins Jr., known as Woody Jenkins (born January 3, 1947), is a newspaper editor in Baton Rouge and Central City, Louisiana, who served as a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1972 to 2000 and waged three unsucc ...

of Baton Rouge for the U.S. Senate against Democrat Mary Landrieu

Mary Loretta Landrieu ( ; born November 23, 1955) is an American entrepreneur and politician who served as a United States senator from Louisiana from 1997 to 2015. A member of the Democratic Party, Landrieu served as the Louisiana State Treas ...

of New Orleans, and Governor Murphy J. "Mike" Foster Jr. seeking re-election in 1999. His opponent was African-American Democratic Congressman Bill Jefferson

William Jennings Jefferson (born March 14, 1947) is an American former politician from Louisiana whose career ended after his corruption scandal and conviction. He served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for nine terms from 1991 ...

of New Orleans.

Political legacy

Davis established a State Retirement System and funding of more than $100 million in public improvements, while leaving the state with a $38 million surplus after his first term. During his second term, Davis built theSunshine Bridge

The Sunshine Bridge is a cantilever bridge over the Mississippi River in St. James Parish, Louisiana. Completed in 1963, it carries Louisiana Highway 70 (LA 70), which connects Donaldsonville on the west bank of Ascension Parish with Sorr ...

, the new Louisiana Governor's Mansion

The Louisiana Governor's Mansion is the official residence of the governor of Louisiana and their family. The Governor’s Mansion was built in 1963 when Jimmie Davis was Governor of Louisiana. The Mansion overlooks Capital Lake near the Louisia ...

, and Toledo Bend Reservoir

Toledo Bend Reservoir is a reservoir on the Sabine River between Texas and Louisiana. The lake has an area of 185,000 acres (749 km2), the largest man-made body of water partially in both Louisiana and Texas, the largest in the South, and ...

, all criticized at the time, but later recognized as beneficial to the state. Davis coordinated the pay periods of state employees, who had sometimes received their checks a week late, a particular hardship to those with low earnings.

Earl Long once remarked that Davis was so relaxed and low-key that one could not "wake up Jimmie Davis with an earthquake".

Public relations specialist Gus Weill

Gus Weill, Sr. (March 12, 1933 – April 13, 2018), was an American author, public relations specialist, and political consultant originally from Lafayette, Louisiana, Lafayette, Louisiana.

Background

Weill graduated in 1955 from Louisiana Sta ...

, who worked in the Davis campaign in 1959, wrote a biography of the former governor in 1977, entitled ''You Are My Sunshine,'' based on Davis' best-known song.

Personal life

Davis's first wife, the former Alvern Adams, the daughter of a physician in Shreveport, was the first lady while he was governor during both terms. Two years after her death in 1967, Davis married Anna Gordon, born Effie Juanita Carter (February 15, 1917 – March 5, 2004). A founding member of the gospel quartet ''The Chuck Wagon Gang'' along with her father, a sister and a brother, she had been given the stage name "Anna" during the mid-1930s. Davis was a longtime fan of the group, who were gospel music pioneers with more than 36 million records sold in forty years of affiliation with Columbia Records. Out of office, Davis resided primarily in Baton Rouge but made numerous singing appearances, particularly in churches throughout the United States. Davis died on November 5, 2000. He had suffered a fall in his home some ten months earlier and may have had a stroke in his last days. He is interred alongside his first wife at the Jimmie Davis Tabernacle Cemetery in his native Beech Springs community near Quitman. Jim Davis was cremated. Davis was aged 101 years and 55 days, which made him the longest-lived of all U.S. state governors at the time of his death. Davis held this record until March 18, 2011, whenAlbert Rosellini

Albert Dean Rosellini (January 21, 1910 – October 10, 2011) was an American politician who served as the 15th governor of Washington from 1957 to 1965 and was both the first Italian-American and Roman Catholic governor elected west of the ...

of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

achieved a greater lifespan of 101 years, 56 days.

Honors

The Jimmie Davis Bridge over the Red River connects Shreveport andBossier City

Bossier City ( ) is a city in Bossier Parish in the northwestern region of the U.S. state of Louisiana in the United States. It is the second most populous city in the Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan statistical area. In 2020, it had a ...

via Louisiana Highway 511. It was named in his honor during his second term as governor.

The Jimmie Davis Tabernacle is located near Weston in Jackson Parish. The tabernacle hosts occasional gospel singing. At the site is a replica of the Davis homestead (c. 1900) and of the Peckerwood Hill Store, an old general store that served the community.

Jimmie Davis State Park is located on Caney Lake (not to be confused with Caney Lakes Recreation Area Caney may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Caney, Kansas

* Caney, Kentucky

* Pippa Passes, Kentucky, known to its inhabitants as Caney or Caney Creek

* Caney, Oklahoma, in Atoka County

* Caney, Cherokee County, Oklahoma

Caney is a censu ...

near Minden) southwest of Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

.

Davis was posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award - an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication – material published after the author's death

* ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1987

* ''Posthumous'' (E ...

inducted into the Delta Music Museum Hall of Fame in Ferriday, Louisiana.

Davis was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame

The Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame was established in 1970 by the Nashville Songwriters Foundation, Inc. in Nashville, Tennessee, United States. A non-profit organization, its objective is to honor and preserve the songwriting legacy that is ...

in 1971, the Country Music Hall of Fame

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Tennessee, is one of the world's largest museums and research centers dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of American vernacular music. Chartered in 1964, the museum has amas ...

in 1972, the Southern Gospel Music Association

The Southern Gospel Music Association (''SGMA'') is a non-profit corporation formed as an association of southern gospel music singers, songwriters, fans, and industry workers. Membership is acquired and maintained through payment of annual dues. T ...

Hall of Fame in 1997 and The Louisiana Music Hall of Fame

The Louisiana Music Hall of Fame (LMHOF) is a non-profit hall of fame based in Baton Rouge, the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana, that seeks to honor and preserve the state's music culture and heritage and to promote education about the state ...

in 2008.

In 1993, Davis was among the first thirteen inductees of the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame The Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame is a museum and hall of fame located in Winnfield, Louisiana. Created by a 1987 act of the Louisiana State Legislature, it honors the best-known politicians and political journalists in the state.

H ...

in Winnfield

Winnfield is a small city in, and the parish seat of, Winn Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 5,749 at the 2000 census, and 4,840 in 2010. Three governors of the state of Louisiana were from Winnfield.

.

The Hall of Fame periodically issues the "Friends of Jimmie Davis Award". In 2005, the award was presented to then U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

Ted Stevens

Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (November 18, 1923 – August 9, 2010) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a U.S. Senator from Alaska from 1968 to 2009. He was the longest-serving Republican Senator in history at the time he left ...

, an Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

Republican, who once hosted Davis in a concert at the Kennedy Center

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (formally known as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts, and commonly referred to as the Kennedy Center) is the United States National Cultural Center, located on the Potom ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Speaking at the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame, Stevens recalled having been with both Davis and Ronald Reagan, when Reagan was contemplating his first run for governor of California and asked Davis for political advice. Stevens joined the Jimmie Davis Band in a rendition of "You Are My Sunshine".

The 2006 recipient of the "Friends of Jimmie Davis" award was the late former State Senator B. G. Dyess

B is the second letter of the Latin alphabet.

B may also refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Astronomy

* Astronomical objects in the List of dark nebulae#Barnard objects, Barnard list of dark nebulae (abbreviation B)

* Latitude (''b ...

, a Baptist minister from Rapides Parish

Rapides Parish () (french: Paroisse des Rapides) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 131,613. The parish seat is Alexandria, which developed along the Red River of the South. ''Rapides ...

.

The Davis archives of papers and photographs is housed in the "You Are My Sunshine" Collection of the Linus A. Sims Memorial Library at Southeastern Louisiana University

Southeastern Louisiana University (Southeastern) is a public university in Hammond, Louisiana. It was founded in 1925 by Linus A. Sims as Hammond Junior College. Sims succeeded in getting the campus moved to north Hammond in 1928, when it becam ...

in Hammond.

Davis believed that his singing career enhanced his political prospects. He once told Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

Republican Ronnie Thompson, a mayor of Macon and fellow musician: "If you want to have any success in politics, sing softly and carry a big guitar," a play on an old Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

adage.Davis, quoted in Eric Welch, "Gospel-singing Jeweler Is 'Country' Candidate", ''Macon Telegraph'', 1967 August 26, p. A1.

Filmography

Davis had several appearances in movies (usually or always as himself), including: *1942: '' Strictly in the Groove'' *1942: ''Riding Through Nevada

''Riding Through Nevada'' is a 1942 American Western film directed by William Berke and written by Gerald Geraghty. The film stars Charles Starrett, Shirley Patterson, Arthur Hunnicutt, Jimmie Davis, Clancy Cooper and Davison Clark. The film ...

''

*1943: '' Frontier Fury''

*1944: ''Cyclone Prairie Rangers

''Cyclone Prairie Rangers'' is a 1944 American Western film directed by Benjamin H. Kline and written by Elizabeth Beecher. The film stars Charles Starrett, Dub Taylor, Constance Worth, Jimmie Davis and Jimmy Wakely. The film was released on N ...

''

*1947: ''Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

''

*1949: '' Mississippi Rhythm''

*1950: ''Square Dance Katy

''Square Dance Katy'' is a 1950 American musical film directed by Jean Yarbrough and written by Warren Wilson. The film stars Barbara Jo Allen, Jimmie Davis, Phil Brito, Virginia Welles, Warren Douglas and Sheila Ryan. The film was released on ...

''

See also

* List of governors of Louisiana * Jim Flynn, a writer encouraged when Davis signed his first song writing contractReferences

Sources

* Toru Mitsui (1998). "Jimmie Davis." In ''The Encyclopedia of Country Music.'' Paul Kingsbury, Ed. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 136. * Kevin S. Fontenot, "You Can't Fight a Song: Country Music in Jimmie Davis' Gubernatorial Campaigns," ''Journal of Country Music'' (2007).External links

*State of Louisiana Biography

Cemetery Memorial

by La-Cemeteries

Listen to Jimmie singing "She's a Real Hum Dinger"

Jimmie Davis recordings

at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

an

at

Southeastern Louisiana University

Southeastern Louisiana University (Southeastern) is a public university in Hammond, Louisiana. It was founded in 1925 by Linus A. Sims as Hammond Junior College. Sims succeeded in getting the campus moved to north Hammond in 1928, when it becam ...

in Hammond.

*

*Southern Gospel Music Association

The Southern Gospel Music Association (''SGMA'') is a non-profit corporation formed as an association of southern gospel music singers, songwriters, fans, and industry workers. Membership is acquired and maintained through payment of annual dues. T ...

Hall of Fame and Museum

{{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, Jimmie

1899 births

2000 deaths

Educators from Louisiana

American actor-politicians

American male actors

American male singer-songwriters

Baptists from Louisiana

American centenarians

American country singer-songwriters

American gospel singers

Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

Democratic Party governors of Louisiana

Men centenarians

People from Jackson Parish, Louisiana

Politicians from Shreveport, Louisiana

Musicians from Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Louisiana Christian University alumni

Louisiana State University alumni

Louisiana Democrats

Members of the Louisiana Public Service Commission

20th-century American businesspeople

American male composers

20th-century American composers

American performers of Christian music

Southern gospel performers

Decca Records artists

Lawrence Welk

Politicians from Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Musicians from Shreveport, Louisiana

20th-century American singers

20th-century American politicians

Old Right (United States)

American anti-communists

20th-century American male singers

Singer-songwriters from Louisiana

Louisiana Dixiecrats