Jefferson C. Davis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jefferson Columbus Davis (March 2, 1828 – November 30, 1879) was a regular officer of the

Davis was born in

Davis was born in

In September 22, two days after Davis received his initial orders from Nelson, he was summoned to the

In September 22, two days after Davis received his initial orders from Nelson, he was summoned to the

A short time later, General Nelson entered the hotel and went to the front desk. Davis approached Nelson, asking for an apology for the offense that Nelson had previously made. Nelson dismissed Davis and said, "Go away you damned puppy, I don't want anything to do with you!" Davis took in his hand a registration card and, while he confronted Nelson, took his anger out on the card, first by gripping it and then by wadding it up into a small ball, which he took and flipped into Nelson's face. Nelson stepped forward and slapped Davis with the back of his hand in the face. Nelson then looked at the governor and asked, "Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?" Morton said, "No sir." Then, Nelson turned and left for his room.

That set the events in motion. Davis asked a friend from the Mexican–American War if he had a pistol, which he did not. He then asked another friend, Thomas W. Gibson, from whom he got a pistol. Immediately, Davis went down the corridor towards Nelson's office, where he was now standing. He aimed the pistol at Nelson and fired. The bullet hit Nelson in the chest and tore a small hole in the heart, mortally wounding the large man. Nelson still had the strength to make his way to the hotel stairs and to climb a floor before he collapsed. By then, a crowd started to gather around him and carried Nelson to a nearby room, laying him on the floor. The hotel proprietor, Silas F. Miller, came rushing into the room to find Nelson lying on the floor. Nelson asked of Miller, "Send for a clergyman; I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered." Reverend J. Talbot was called, who responded, as well as a doctor. Several people came to see Nelson, including Reverend Talbot, Surgeon Murry, General Crittenden and General Fry. The shooting had occurred at 8:00 am, and by 8:30, Nelson was dead.

A short time later, General Nelson entered the hotel and went to the front desk. Davis approached Nelson, asking for an apology for the offense that Nelson had previously made. Nelson dismissed Davis and said, "Go away you damned puppy, I don't want anything to do with you!" Davis took in his hand a registration card and, while he confronted Nelson, took his anger out on the card, first by gripping it and then by wadding it up into a small ball, which he took and flipped into Nelson's face. Nelson stepped forward and slapped Davis with the back of his hand in the face. Nelson then looked at the governor and asked, "Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?" Morton said, "No sir." Then, Nelson turned and left for his room.

That set the events in motion. Davis asked a friend from the Mexican–American War if he had a pistol, which he did not. He then asked another friend, Thomas W. Gibson, from whom he got a pistol. Immediately, Davis went down the corridor towards Nelson's office, where he was now standing. He aimed the pistol at Nelson and fired. The bullet hit Nelson in the chest and tore a small hole in the heart, mortally wounding the large man. Nelson still had the strength to make his way to the hotel stairs and to climb a floor before he collapsed. By then, a crowd started to gather around him and carried Nelson to a nearby room, laying him on the floor. The hotel proprietor, Silas F. Miller, came rushing into the room to find Nelson lying on the floor. Nelson asked of Miller, "Send for a clergyman; I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered." Reverend J. Talbot was called, who responded, as well as a doctor. Several people came to see Nelson, including Reverend Talbot, Surgeon Murry, General Crittenden and General Fry. The shooting had occurred at 8:00 am, and by 8:30, Nelson was dead.

Davis was a capable commander, but because of the murder of Nelson, he never received a full promotion higher than brigadier general of volunteers. He, however, received a brevet promotion to

Davis was a capable commander, but because of the murder of Nelson, he never received a full promotion higher than brigadier general of volunteers. He, however, received a brevet promotion to

Jefferson Columbus Davis Papers

at

Jefferson C. Davis Collection

Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, Jefferson C. 1828 births 1879 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American people of the Indian Wars Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery People from Clark County, Indiana Louisville, Kentucky, in the American Civil War People of the Modoc War People of Indiana in the American Civil War People of Kentucky in the American Civil War Union Army generals Commanders of the Department of Alaska People from Indiana in the Mexican–American War 19th-century American politicians

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, known for the similarity of his name to that of Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confed ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

and for his killing of a superior officer in 1862.

Davis's distinguished service in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

earned him high prestige at the outbreak of the Civil War, when he led Union troops through Southern Missouri to Pea Ridge, Arkansas, being promoted to Brigadier General after that significant victory. Following the Siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth (also known as the first Battle of Corinth) was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry ...

, he was granted home leave on account of exhaustion, but returned to duty on hearing of Union defeats in Kentucky, where he reported to General William "Bull" Nelson at Louisville in September 1862. Nelson was dissatisfied with his performance, and insulted him in front of witnesses. A few days later, Davis demanded a public apology, but instead the two officers argued noisily and physically, concluding in Davis mortally wounding Nelson with a pistol.

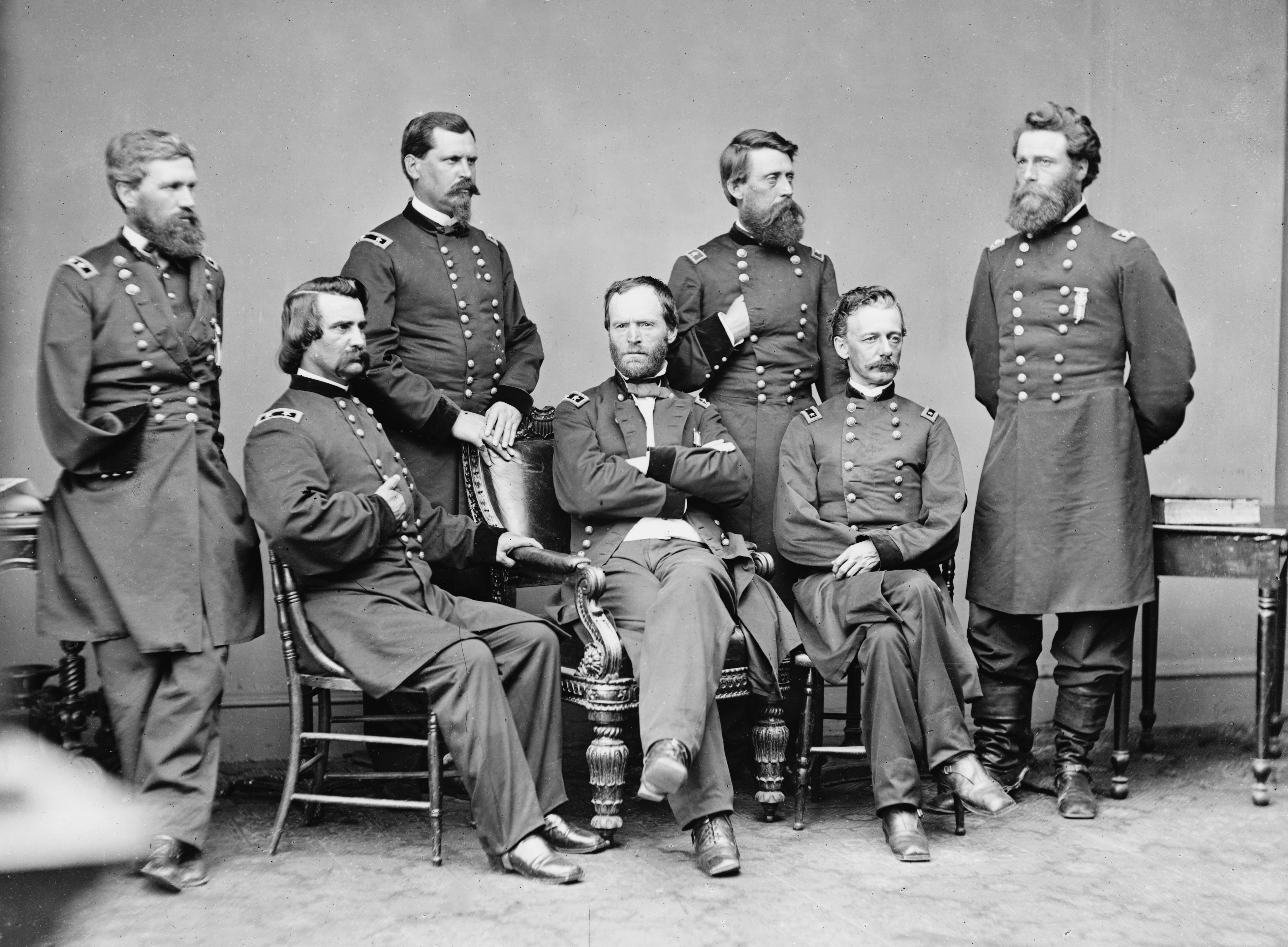

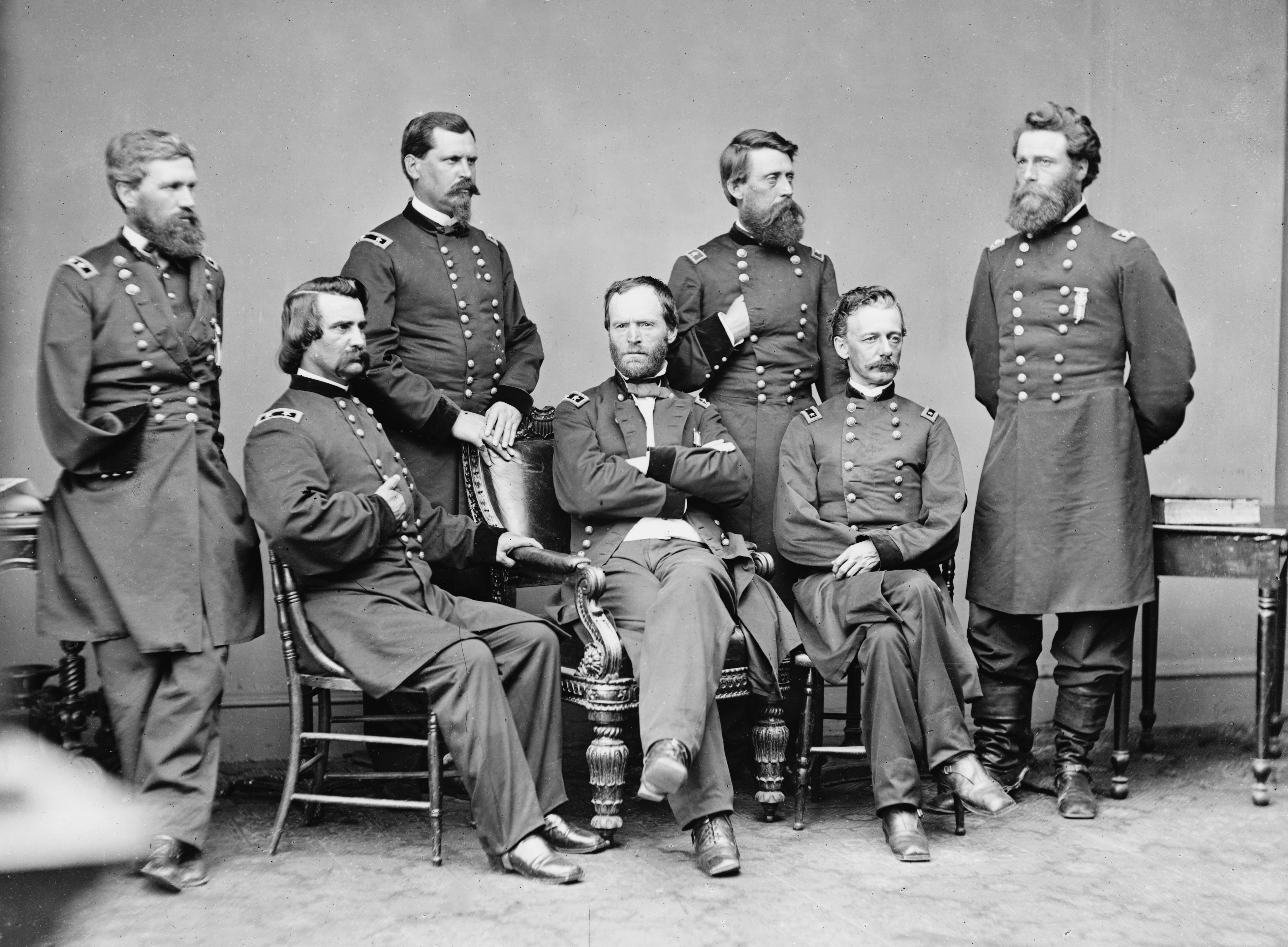

Davis avoided conviction due to the shortage of experienced commanders in the Union Army, but the incident hampered his chances for promotion. He served as a corps commander under William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

during his March to the Sea in 1864. After the war, Davis was the first commander of the Department of Alaska from 1867 to 1870, and assumed field command during the Modoc War

The Modoc War, or the Modoc Campaign (also known as the Lava Beds War), was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc people and the United States Army in northeastern California and southeastern Oregon from 1872 to 1873. Eadweard M ...

of 1872–1873.

Early life

Davis was born in

Davis was born in Clark County, Indiana

Clark County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana, located directly across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. At the 2020 census, the population was 121,093. The county seat is Jeffersonville. Clark County is part of the Louisvill ...

, near present-day Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

. He was born to William Davis, Jr. (1800–1879) and Mary Drummond-Davis (1801–1881), the oldest of their eight children. His father was a farmer. His parents came from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, and like many at the time including President Abraham Lincoln's family, moved to Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

.

Early military career

When Davis was 19 years old, in June 1847, he joined the 3rd Indiana Volunteers. He enlisted as a soldier during the Mexican–American War. Through the war, he received promotions through the rank ofsergeant

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other ...

. He received a commission as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

, in the First U.S. Artillery, in June 1848. He received the promotion for bravery at Buena Vista Buena Vista, meaning "good view" in Spanish, may refer to:

Places Canada

*Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador, with the name being originally derived from “Buena Vista”

*Buena Vista, Saskatchewan

* Buena Vista, Saskatoon, a neighborhood in ...

. He joined the 1st Artillery in October 1848 at Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attac ...

, outside of Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

. He later moved south to Fort Washington, Maryland, just outside Washington DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and again to the coast of Mississippi. He was promoted again to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

in February 1852 and was transferred to Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

in 1853 and on to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. In 1857, he was stationed again in Fort McHenry moving to Florida in 1858. In the summer of 1858, he received a transfer to Fort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of palmetto logs, inspired the flag and n ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. Fort Moultrie was located near Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

and Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. He remained in South Carolina until Fort Sumter was evacuated at the beginning of the Civil War, in 1861.

Civil War

When the war began in April 1861, Davis was an officer in the garrison atFort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

when it was bombarded by Confederate forces. The following month he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and given the task of raising a regiment in Indiana. Additionally, he was given responsibility over the commissary and supply. He requested assignment as a regimental commander, growing bored with his garrison duties. After the death of Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon (July 14, 1818 – August 10, 1861) was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War. He is noted for his actions in Missouri in 1861, at the beginning of the conflict, to forestall secret secessionist plans of th ...

and the loss at Wilson's Creek, his request was gratefully accepted. His experience as a regular in the federal army made him a rare commodity, and he was given command of the 22nd Indiana Infantry Regiment, receiving a promotion to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

.

Missouri

By the end of August, Davis received orders to succeed Brigadier GeneralUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

as commander of forces in northwestern Missouri. His headquarters were in Jefferson City, Missouri

Jefferson City, informally Jeff City, is the capital of Missouri, United States. It had a population of 43,228 at the 2020 census, ranking as the 15th most populous city in the state. It is also the county seat of Cole County and the principa ...

, with approximately 16,000 Confederate troops nearby. General Fremont had great concerns that the Confederate troops, commanded by Generals McCullough and Sterling Price, would set their eyes on St. Louis as a potential target. Davis's command grew quickly, starting at 12,000 at the beginning of September and expanding to 18,000 to 20,000 by the end of the month. Initially, Davis spent time building fortifications to fend off possible attack on the capital city. Once his defensive plan had been completed, he planned an offensive campaign, but materiel was refused to Davis. That may have contributed to losing the Battle of Lexington

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

.

In December 1861, he took command of the 3rd Division, Army of the Southwest

The Army of the Southwest was a Union Army that served in the Trans-Mississippi Theater during the American Civil War. This force was also known as the Army of Southwest Missouri.

History

Army of the Southwest

Created on Christmas Day, 1861, th ...

. He pursued Confederate troops through southern Missouri, as they retreated toward and into Arkansas. In March 1862, his division attacked the Confederates at the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place in the American Civil War near Leetown, Arkansas, Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. United States, Federal f ...

. Davis's distinguished service at Pea Ridge was rewarded in May 1862, and he received a field promotion commensurate with his command of a Division Commander, brevetted

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

to Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

.

At the Siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth (also known as the first Battle of Corinth) was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry ...

, he commanded the 4th Division, Army of the Mississippi

Army of the Mississippi was the name given to two Union armies that operated around the Mississippi River, both with short existences, during the American Civil War.

History 1862

The first army was created on February 23, 1862, with Maj. Gen ...

.

Leave authorized

In the late summer of 1862, Davis became ill, probably caused by exhaustion. He wrote to his commander, General Rosecrans, requesting a few weeks' leave. Davis stated, "After twenty-one months of arduous service.... I find myself compelled by physical weakness and exhaustion to ask... for a few weeks' respite from duty...." On August 12, 1862, the Army of Mississippi issued General Rosecrans' response in Special Order No. 208, authorizing General Davis 20 days of convalescence. Davis headed for home in Indiana to rest and recuperate. While Davis was on leave, the state of affairs in Kentucky became quite precarious. TheArmy of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed Maj. Gen. ...

, commanded by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

, was taking aim on Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020 ...

. Three hundred miles of railway lines lay between Louisville and Chattanooga, and Confederate forces were making constant work tearing up the tracks. The railroads provided the needed supplies to Union troops on the move and so Buell was forced to split his forces and to send General William "Bull" Nelson back north to Kentucky to take charge of the area. When Nelson arrived in Louisville, he found Major General Horatio G. Wright

Horatio Gouverneur Wright (March 6, 1820 – July 2, 1899) was an engineer and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He took command of the VI Corps in May 1864 following the death of General John Sedgwick. In this capacity, he ...

had been sent by the President to take control, putting Buell second in command.

In late August, two Confederate armies, under the command of Major General Edmund Kirby Smith

General Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the India ...

and General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Wester ...

, moved into Kentucky and Tennessee on the offensive to drive Union forces from Kentucky. Smith's Army of East Tennessee had approximately 19,000 men and Bragg's Army of Tennessee had approximately 35,000. On August 23, 1862, Confederate cavalry met and defeated Union troops at the Battle of Big Hill. That was only a prelude to the bigger battle ahead; on August 29, 1862, portions of Smith's army met an equal portion of Nelson's force that numbered between 6,000 and 7,000. The two-day Battle of Richmond, ending on August 30, was an overwhelming Confederate victory in all aspects: Union casualties numbered over 5,000, compared to the 750 Confederate casualties, and considerable ground was lost, including Richmond; Lexington; and the state capital, Frankfort. Further loss at the battle occurred with the capture of Brigadier General Mahlon D. Manson and the wounding of General Nelson, injured in the neck, who was forced to retreat back to Louisville to prepare for the presumed assault. The Confederates were now in a position to aim northward to take the fight to the enemy.

Louisville

Davis was quite aware of the circumstances in the neighboring state to the south; Smith was able to strike atCincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

, Bragg and/or Smith at Louisville. Davis, still on convalescence, reported to General Wright, whose headquarters were in Cincinnati to offer his services. Wright ordered Davis to report to Nelson. In Louisville, Davis was put in charge of organizing and arming its citizens, preparing for its defense.

Nelson was quite an imposing figure over Davis. William Nelson got his nickname, "Bull," in no small part to his stature. Nelson was 300 pounds and six feet two inches and was described as being "in the prime of life, in perfect health." Davis was quite small in comparison, measuring five feet nine inches and reportedly only 125 pounds.

Dismissal from Louisville

In September 22, two days after Davis received his initial orders from Nelson, he was summoned to the

In September 22, two days after Davis received his initial orders from Nelson, he was summoned to the Galt House

The Galt House Hotel is a 25-story, 1,300-room hotel in Louisville, Kentucky, established in 1972. It is named for a nearby historic hotel erected in 1835 and demolished in 1921. The Galt House is the city's only hotel on the Ohio River.

Origi ...

, where Nelson had made his headquarters. Nelson inquired on how the recruitment was going and how many men had been mustered. Davis replied that he did not know. As Nelson asked his questions and received only short answers that Davis was unaware of any specifics, Nelson became enraged and expelled Davis from Louisville. General James Barnet Fry

James Barnet Fry (February 22, 1827 – July 11, 1894) was an American soldier and prolific author of historical books.

Family and Early career

Fry, who was born in Carrollton, Illinois, was the first child of General Jacob G. Fry (September ...

, described as a close friend of Davis, was present and later wrote of the events surrounding the death of Nelson. Fry states:

Davis arose and remarked, in a cool, deliberate manner: "General Nelson, I am a regular soldier, and I demand the treatment due to me as a general officer." Davis then stepped across to the door of the Medical Director's room, both doors being open... and said: "Dr Irwin, I wish you to be a witness to this conversation." At the same time Nelson said: "Yes, doctor, I want you to remember this." Davis then said to Nelson: "I demand from you the courtesy due to my rank." Nelson replied: "I will treat you as you deserve. You have disappointed me; you have been unfaithful to the trust which I reposed in you, and I shall relieve you at once. You are relieved from duty here and you will proceed to Cincinnati and report to General Wright." Davis said: "You have no authority to order me." Nelson turned toward the Adjutant-General and said: "Captain, if General Davis does not leave the city by nine o'clock tonight, give instructions to the Provost-Marshal to see that he shall be put across the Ohio River."

Reassigned to Louisville

Davis made his way to Cincinnati and reported to General Wright within a few days. Within the same week, Buell returned to Louisville and took command from Nelson. Wright then felt that with Buell in command at Louisville, there was no need to keep Davis from Louisville, where his leadership was desperately needed and so sent Davis back to there. Davis arrived in Louisville in the afternoon on Sunday, September 28, and reported to the Galt House early the next morning, at breakfast time. The Galt House continued to serve as the command's headquarters for both Buell and Nelson. That, like on most other mornings, was the meeting place for many of the most prominent military and civil leaders. When Davis arrived and looked around the room, he saw many familiar faces and joinedOliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

, Indiana's governor.

Killing of Nelson

A short time later, General Nelson entered the hotel and went to the front desk. Davis approached Nelson, asking for an apology for the offense that Nelson had previously made. Nelson dismissed Davis and said, "Go away you damned puppy, I don't want anything to do with you!" Davis took in his hand a registration card and, while he confronted Nelson, took his anger out on the card, first by gripping it and then by wadding it up into a small ball, which he took and flipped into Nelson's face. Nelson stepped forward and slapped Davis with the back of his hand in the face. Nelson then looked at the governor and asked, "Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?" Morton said, "No sir." Then, Nelson turned and left for his room.

That set the events in motion. Davis asked a friend from the Mexican–American War if he had a pistol, which he did not. He then asked another friend, Thomas W. Gibson, from whom he got a pistol. Immediately, Davis went down the corridor towards Nelson's office, where he was now standing. He aimed the pistol at Nelson and fired. The bullet hit Nelson in the chest and tore a small hole in the heart, mortally wounding the large man. Nelson still had the strength to make his way to the hotel stairs and to climb a floor before he collapsed. By then, a crowd started to gather around him and carried Nelson to a nearby room, laying him on the floor. The hotel proprietor, Silas F. Miller, came rushing into the room to find Nelson lying on the floor. Nelson asked of Miller, "Send for a clergyman; I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered." Reverend J. Talbot was called, who responded, as well as a doctor. Several people came to see Nelson, including Reverend Talbot, Surgeon Murry, General Crittenden and General Fry. The shooting had occurred at 8:00 am, and by 8:30, Nelson was dead.

A short time later, General Nelson entered the hotel and went to the front desk. Davis approached Nelson, asking for an apology for the offense that Nelson had previously made. Nelson dismissed Davis and said, "Go away you damned puppy, I don't want anything to do with you!" Davis took in his hand a registration card and, while he confronted Nelson, took his anger out on the card, first by gripping it and then by wadding it up into a small ball, which he took and flipped into Nelson's face. Nelson stepped forward and slapped Davis with the back of his hand in the face. Nelson then looked at the governor and asked, "Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?" Morton said, "No sir." Then, Nelson turned and left for his room.

That set the events in motion. Davis asked a friend from the Mexican–American War if he had a pistol, which he did not. He then asked another friend, Thomas W. Gibson, from whom he got a pistol. Immediately, Davis went down the corridor towards Nelson's office, where he was now standing. He aimed the pistol at Nelson and fired. The bullet hit Nelson in the chest and tore a small hole in the heart, mortally wounding the large man. Nelson still had the strength to make his way to the hotel stairs and to climb a floor before he collapsed. By then, a crowd started to gather around him and carried Nelson to a nearby room, laying him on the floor. The hotel proprietor, Silas F. Miller, came rushing into the room to find Nelson lying on the floor. Nelson asked of Miller, "Send for a clergyman; I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered." Reverend J. Talbot was called, who responded, as well as a doctor. Several people came to see Nelson, including Reverend Talbot, Surgeon Murry, General Crittenden and General Fry. The shooting had occurred at 8:00 am, and by 8:30, Nelson was dead.

Arrest and release

Davis did not leave the vicinity of Nelson. He did not run or evade capture. He was simply taken into military custody by Fry and confined to an upper room in the Galt House. Davis attested to Fry what had happened. Fry wrote that while Davis was improperly treated for a man of his rank, he never pursued any legal recourse, which there was available to him. Fry attested that Davis was quite forthcoming and even included the fact that it was he who flipped a paper-wad in the face of Nelson. Davis wanted to confront Nelson publicly and wanted Nelson's disrespect to be witnessed. What Davis had not accounted for was Nelson's physical assault. Everything then spiraled out of control. Many in close confidence with Nelson wanted to see quick justice with regards to Davis. There were a few, including General William Terrill, who wanted to see Davis hanged on the spot. Buell weighed in by saying that Davis' conduct was inexcusable. Fry stated that Buell regarded the actions as "a gross violation of military discipline." Buell went on to telegraph GeneralHenry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

, General in Chief of all Armies:

It was Major General Horatio G. Wright

Horatio Gouverneur Wright (March 6, 1820 – July 2, 1899) was an engineer and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He took command of the VI Corps in May 1864 following the death of General John Sedgwick. In this capacity, he ...

who came to Davis's aid by securing his release and returning him to duty. Davis avoided conviction for the murder because there was a need for experienced field commanders in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

. Fry stated in his journal of Wright's comments,

Davis appealed to me, and I notified him that he should no longer consider himself in arrest.... I was satisfied that Davis acted purely on the defensive in the unfortunate affair, and I presumed that Buell held very similar views, as he took no action in the matter after placing him in arrest.Davis was released from custody on October 13, 1862. Military regulations required charges to be formally made against the accused within 45 days of the arrest. The charges never came possibly because larger events, such as the launching of Buell's campaign in Kentucky five days later, overshadowed the Davis-Nelson affair.

Aftermath

There was no trial or any significant confinement since it appears that Davis was staying at the Galt House without guard, as based partly on Wright's statement. Davis simply walked away and returned to duty as if nothing had ever happened.Western Campaign

Davis was a capable commander, but because of the murder of Nelson, he never received a full promotion higher than brigadier general of volunteers. He, however, received a brevet promotion to

Davis was a capable commander, but because of the murder of Nelson, he never received a full promotion higher than brigadier general of volunteers. He, however, received a brevet promotion to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

of volunteers on August 8, 1864 for his service at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought on June 27, 1864, during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the most significant frontal assault launched by Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman against the Confederate Army of Ten ...

, and he was appointed commanding officer of the XIV Corps 14 Corps, 14th Corps, Fourteenth Corps, or XIV Corps may refer to:

* XIV Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XIV Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World ...

during the Atlanta Campaign, which he retained until the end of the war. He received a brevet promotion to brigadier general in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

on March 20, 1865.

During Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

, Davis's actions during the Ebenezer Creek passing and ruthlessness toward former slaves have caused his legacy to be clouded in continued controversy. As Sherman's army proceeded toward Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, on December 9, 1864, Davis ordered a pontoon bridge removed before the African-American refugees, who were following his corps, could cross the creek. Several hundred were captured by the Confederate cavalry or drowned in the creek while they attempted to escape.

Postbellum career

Department of Alaska

After the Civil War, Davis continued service with the army, becoming colonel of the23rd Infantry Regiment

The 23rd Infantry Regiment is an infantry regiment in the United States Army. A unit with the same name was formed on 26 June 1812 and saw action in 14 battles during the War of 1812.

In 1815 it was consolidated with the 6th, 16th, 22nd, ...

in July 1866. He was the first commander of the Department of Alaska and established a fort at Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

on October 29, 1867. from March 18, 1868, to June 1, 1870. He ordered Russian residents of Sitka, Alaska, to leave their homes since he maintained that they were needed for Americans.

Modoc War

Davis gained fame when he assumed command of the US forces in California and Oregon during theModoc War

The Modoc War, or the Modoc Campaign (also known as the Lava Beds War), was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc people and the United States Army in northeastern California and southeastern Oregon from 1872 to 1873. Eadweard M ...

of 1872–1873, after General Edward Canby

Edward Richard Sprigg Canby (November 9, 1817 – April 11, 1873) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War.

In 1861–1862, Canby commanded the Department of New Mexico, defeating the Confederate Gen ...

and Reverend Eleazer Thomas had been assassinated during peace talks. Davis's presence in the field restored the soldiers' confidence after their recent setbacks against the Modoc. Davis's campaign resulted in the Battle of Dry Lake (May 10, 1873) and the eventual surrender of notable leaders, such as Hooker Jim

Hooker Jim (1851–1879), or Hooka Jim, was a Modoc warrior who played a pivotal role in the Modoc War. Hooker Jim was the son-in-law of tribal medicine man Curley Headed Doctor. After white settlers massacred Modoc women and children contempora ...

and Captain Jack Captain Jack may refer to:

People

* Calico Jack (1683–1720), a pirate in the 18th century

* Captain Jack (Hawaiian) (died 1831), Naihekukui, commander of Kamehameha's fleet and father of Kalama

* Captain Jack (fl. 1830s on), Kaurna man in c ...

.

1877 general strike

During the1877 St. Louis general strike

The 1877 St. Louis general strike was one of the first general strikes in the United States. It grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, ...

, Davis arrived in St. Louis, commanding 300 men and two Gatling guns, but refused on urging to quell strikers or run the trains. Stating that doing so would be beyond his orders to protect government and public property.

Death

Davis died inChicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, on November 30, 1879. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high point ...

, Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Mar ...

.

In fiction

Jefferson C. Davis is a character in the historical novel ''Forty-Ninth'' by Boris Pronsky and Craig Britton.See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

* Louisville in the American Civil War

Louisville in the American Civil War was a major stronghold of Union forces, which kept Kentucky firmly in the Union. It was the center of planning, supplies, recruiting and transportation for numerous campaigns, especially in the Western Theat ...

* '' Sherman's March''

* Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Levstik, Frank R. "Jefferson Columbus Davis." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . *External links

Jefferson Columbus Davis Papers

at

the Newberry Library

The Newberry Library is an independent research library, specializing in the humanities and located on Washington Square in Chicago, Illinois. It has been free and open to the public since 1887. Its collections encompass a variety of topics rela ...

*

*

Jefferson C. Davis Collection

Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library

National Park Service

{{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, Jefferson C. 1828 births 1879 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American people of the Indian Wars Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery People from Clark County, Indiana Louisville, Kentucky, in the American Civil War People of the Modoc War People of Indiana in the American Civil War People of Kentucky in the American Civil War Union Army generals Commanders of the Department of Alaska People from Indiana in the Mexican–American War 19th-century American politicians