Jean de Montluc on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jean de Monluc, 1508 to 12 April 1579, was a French nobleman, clergyman, diplomat and courtier. He was the second son of François de Lasseran de Massencome, a member of the Monluc family; and Françoise d' Estillac. His birthplace is unknown, but it has been observed that his parents spent a great deal of time at their favorite residence at Saint-Gemme in the commune of Saint-Puy near Condom. His elder brother

In 1549 Jean went to Ireland to investigate reports that Con O'Neill,

In 1549 Jean went to Ireland to investigate reports that Con O'Neill,

Blaise de Montluc

Blaise de Monluc, also known as Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Monluc, (24 July 1577) was a professional soldier whose career began in 1521 and reached the rank of marshal of France in 1574. Written between 1570 and 1576, an account o ...

became a soldier and eventually Marshal of France (1574).

Early career

Jean began his religious career as a young Dominican novice, in either their Convent in Condom or the one in Agen. From the beginning he showed outstanding talent as a public speaker. He was introduced to QueenMarguerite de Navarre

Marguerite de Navarre (french: Marguerite d'Angoulême, ''Marguerite d'Alençon''; 11 April 149221 December 1549), also known as Marguerite of Angoulême and Margaret of Navarre, was a princess of France, Duchess of Alençon and Berry, and Queen ...

, the sister of King Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

, who often stayed in her chateau at Nérac

Nérac (; oc, Nerac, ) is a commune in the Lot-et-Garonne department, Southwestern France. The composer and organist Louis Raffy was born in Nérac, as was the former Arsenal and Bordeaux footballer Marouane Chamakh, as was Admiral Francois Dar ...

, just north of Condom, and quickly became part of her entourage, abandoning his life as a Dominican friar.

French diplomat

In 1524 Jean de Monluc served as an attaché to the French Embassy in Rome. In 1536, now aProtonotary Apostolic

In the Roman Catholic Church, protonotary apostolic (PA; Latin: ''protonotarius apostolicus'') is the title for a member of the highest non-episcopal college of prelates in the Roman Curia or, outside Rome, an honorary prelate on whom the pop ...

, he was again assigned to the Embassy being sent to Rome headed by Bishop Charles Hémard of Mâcon. In 1537 Monluc was sent with a personal ''viva voce'' message from King Francis I to Pasha Khizir Khayr ad-Dîn (Barberousse), the Captain General of the Ottoman fleet, who was beginning a campaign against the coasts of Italy. In July 1537, the Pasha landed at Otranto and captured the city, as well as the Fortress of Castro and the city of Ugento in Apulia. Monluc set off on 6 August, and a meeting took place with the Pasha on 1 September. On his return journey Monluc was received by Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

in a public audience, where embarrassing questions were raised about the rumored poisoning of the Dauphin. Details of his embassy were submitted in a letter to Cardinal du Bellay in Paris. He remained in Rome, attached to the French Embassy, under the Comte de Grignan and then Bishop Jean de Langeac of Limoges, at least until 1540.

In ca. 1542 Monluc was sent on a mission to Venice. His assignment was to explain to the Venetians why it had been a good idea for Francis I to ally himself with the Ottoman Turks. It was a thankless task, and a hopeless mission, but one which used Monluc's great gifts of oratory in the service of the King.

Monluc distinguished himself in several embassies. In 1545, Jean de Monluc went on an embassy for Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, where he joined ambassador Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon.

In 1549 Jean went to Ireland to investigate reports that Con O'Neill,

In 1549 Jean went to Ireland to investigate reports that Con O'Neill, O'Doherty

O'Doherty is a surname, part of the O'Doherty family. Notable persons with that surname include:

*Brian O'Doherty (born 1928), Irish art critic, writer, artist, and academic

*Sir Cahir O'Doherty (1587–1608), last Gaelic Lord of Inishowen in Ire ...

, Manus O'Donnell

Manus O'Donnell (Irish: ''Maghnas Ó Domhnaill'' or ''Manus Ó Domhnaill'', died 1564) was an Irish lord and son of Sir Hugh Dubh O'Donnell. He was an important member of the O'Donnell dynasty based in County Donegal in Ulster.

Early life

Hug ...

and his son Calvagh might join with France against English rule. France would offer military support and obtain Papal funding. He then went to Scotland and met Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. She ...

at Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

in January 1550. His colleague Raymond de Beccarie de Pavie, sieur de Fourqueveaux was not impressed by the Irish chiefs.

Bishop

Jean was appointedbishop of Valence

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Valence (–Die–Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux) (Latin: ''Dioecesis Valentinensis (–Diensis–Sancti Pauli Tricastinorum)''; French: ''Diocèse de Valence (–Die–Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux'') is a diocese of the L ...

-and-Die

Die, as a verb, refers to death, the cessation of life.

Die may also refer to:

Games

* Die, singular of dice, small throwable objects used for producing random numbers

Manufacturing

* Die (integrated circuit), a rectangular piece of a semicondu ...

by King Henry II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder bro ...

in 1553, and confirmed by Pope Julius III on 30 March 1554. He did not visit his diocese, however, until 1558. He was sympathetic to the Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, attacked the cult of images, and made prayers in French, thereby earning him the opprobrium of Rome. He advocated a reunion of Protestantism and Catholicism through the establishment of a common council. The Dean of the Cathedral of Valence collected the evidence and lodged charges of heresy against Monluc in Rome. Sentence was pronounced against him on 14 October 1560. In the same year, on 25 May, a great slaughter of Protestants took place in Valence.

In August 1562 Monluc planned to stop in Valence during one of his trips, but the city was governed by Huguenots, and its captain pursued Monluc, intending to arrest and imprison him. Monluc got away, it seemed, to Annonay, but it too was in the hands of the Huguenots, who chased after and captured him; but he was able to escape again.

Mission to Scotland in 1560

In March 1560,Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

and her husband Francis II of France

Francis II (french: François II; 19 January 1544 – 5 December 1560) was King of France from 1559 to 1560. He was also King consort of Scotland as a result of his marriage to Mary, Queen of Scots, from 1558 until his death in 1560.

He ...

sent Jean to Scotland to meet the former Regent of Scotland, the Earl of Arran. Arran was the leader of the Protestant Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves "the Faithful", were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scotti ...

who had risen against the Catholic rule of Mary of Guise during the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

. Jean first went to London to meet Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

, then travelled with Henry Killigrew to Berwick upon Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census reco ...

on 6 April. They met the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

who was directing English military operations in Scotland in support of the Protestants. Killigrew wrote a note to William Cecil which mentions that he had deliberately taken the journey north as slowly as possible, riding forty miles in a day rather than sixty. During the ride, Jean told Killigrew that he was offended by Elizabeth's efforts to delay him in London, while her army, enabled by the treaty of Berwick had entered Scotland.

Jean gave Norfolk a letter from Elizabeth with instructions to give him safe conduct to Mary of Guise. Norfolk wrote that this would be difficult, because Arran was in the field, the Dowager was in Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

and the French were in Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. On the same day Norfolk got news of the battle at Restalrig

Restalrig () is a small residential suburb of Edinburgh, Scotland (historically, an estate and independent parish).

It is located east of the city centre, west of Craigentinny and to the east of Lochend, both of which it overlaps. Restalrig ...

that commenced the siege of Leith

The siege of Leith ended a twelve-year encampment of French troops at Leith, the port near Edinburgh, Scotland. The French troops arrived by invitation in 1548 and left in 1560 after an English force arrived to attempt to assist in removing the ...

. By 12 April, still in Berwick, Jean told Killigrew that he thought Elizabeth would drive the French from Scotland, and this was the worst of his "imbassagis" and would be his undoing. Eventually, Jean boasted to Killigrew that no man could end the difference by treaty better than he could, and privately told him that he was prepared to make concessions including a French withdrawal from Scotland, excepting the garrisons of Inchkeith

Inchkeith (from the gd, Innis Cheith) is an island in the Firth of Forth, Scotland, administratively part of the Fife council area.

Inchkeith has had a colourful history as a result of its proximity to Edinburgh and strategic location for u ...

and Dunbar Castle

Dunbar Castle was one of the strongest fortresses in Scotland, situated in a prominent position overlooking the harbour of the town of Dunbar, in East Lothian. Several fortifications were built successively on the site, near the English-Scott ...

. Killigrew went into Scotland alone, and spoke to Mary of Guise and the Scottish Lords, securing a hearing for Jean, so "that the world shall not say but that he was heard."

The Lords of the Congregation allowed Jean to enter Scotland on 20 April. Norfolk gave him an eight-day pass to Haddington and the English camp at Leith (Restalrig Deanery). Grey of Wilton let him see Mary of Guise, but prevented him going into Leith and conferring with the French commanders, Henri Cleutin

Henri Cleutin, seigneur d'Oisel et de Villeparisis (1515 – 20 June 1566), was the representative of France in Scotland from 1546 to 1560, a Gentleman of the Chamber of the King of France, and a diplomat in Rome 1564-1566 during the French Wars o ...

, de Martiques and Jacques de la Brosse

Jacques de la Brosse (c. 1485–1562), Cup-bearer, cupbearer to the king, was a sixteenth-century French soldier and diplomat. He is remembered in Scotland for his missions in 1543 and 1560 in support of the Auld Alliance.

Mission of 1543

After ...

.Amongst the Protestant leaders, he spoke to the Earl of Morton

The title Earl of Morton was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1458 for James Douglas of Dalkeith. Along with it, the title Lord Aberdour was granted. This latter title is the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir to the Earl of Morton. ...

and Mary's half-brother Lord James. Amongst his proposals, he asked that the Lords of the Congregation dissolve their league with England, meaning February's treaty of Berwick. Their response was to renew their alliance in a "bande amongst the nobilitie of Scotland" on 27 April 1560, which declared their religious aims and intent to "take plain part with the Queen of England's army."

He was in Newcastle on 10 June and with another French diplomat, de Randan, had a conference with Cecil, and Dr Nicolas Wotton. With a second commission from Mary and Francis he returned to Scotland in June 1560, and took part in the peace talks which culminated in the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives ...

, which he signed "J. Monlucius episcopus Valentinus" on behalf of France, and resulted in the evacuation of French troops from Scotland. The English diplomat Thomas Randolph reported to Killigrew that his bishop had great honour by English and Scots, and was "royally banqueted and entertained."

Inquisition

At the assembly of Fontainebleau in 1560, Monluc was one of the leaders speaking in favor of Condé's demand for full liberty for Protestants. He also participated in theColloquy of Poissy

The Colloquy at Poissy was a religious conference which took place in Poissy, France, in 1561. Its object was to effect a reconciliation between the Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots) of France.

The conference was opened on 9 September in the ...

in September 1561.

On 13 April 1563, Jean de Monluc and seven other French bishops were summoned to Rome by decree of Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

to be examined on charges of heresy by the Roman and Universal Inquisition. Failure to appear would incur excommunication and deprivation of all of their benefices. The principal charge against Monluc was adoption of doctrines of Calvinism. Theodore de Beze had said of Monluc that, preaching in his own diocese, he had made a mixture of the two doctrines and cast blame overtly on several abuses of the Papacy. Degert (1904a), p. 416. Three of his publications had incurred the censure of the Faculty of Theology of the Sorbonne, his ''Instructions chrestiennes'' (1561), the ''Sermons de l' evesque de Valence'' (editions of 1557 and 1559), and the ''Sermons servants a decouvrir... les fautes... de la loy'' (1559). He had been the one to convince the Cardinal de Lorraine to have the Protestants invited to the Colloquy of Poissy in 1561, and he had been one of the bishops who had refused to attend the Mass presided over by the Cardinal d'Armagnac and to receive Holy Communion.

Monluc's most prominent defender and protector, however, was the Queen Mother, Catherine de' Medici, who desired above all peace and stability for the sake of her fragile dynasty. She espoused the notion that Catholics and Huguenots could reason together on their doctrinal differences, and live together in loyalty and service to the Crown. Monluc was her most eager agent. She informed the Papal Nuncio, Prospero de Santacroce, that she was intervening as the natural guardian of the Liberties of the Gallican Church, and that such disputes should be adjudicated and settled in France, not sent to Rome. A dispute over jurisdiction arose between France and the Papacy, but ultimately Pius IV (1559-1565) did nothing to press the issue.

The bishop was declared a heretic and deprived of his benefices, including the Bishopric of Valence-and-Die, on 11 October 1566 by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

(Michele Ghislieri, O.P.). To make certain of his safety, Monluc procured a mandate signed by King Charles IX, granting him relief from appeal, and forbidding any judges, royal agents, or any members of the Chapter of the Diocese of Valence-et-Die to receive or obey any instructions from the new pope, Pius V, or the Roman Inquisition without first having submitted them to the King for his judgment and consent.

Diplomat again

In 1572–1573, Jean de Monluc was the French envoy in Poland to negotiate the election of Henry of Valois, futureHenry III of France

Henry III (french: Henri III, né Alexandre Édouard; pl, Henryk Walezy; lt, Henrikas Valua; 19 September 1551 – 2 August 1589) was King of France from 1574 until his assassination in 1589, as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of ...

, on the Polish throne, in exchange for military support against Russia, diplomatic assistance in dealing with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and financial help. He was not eager and tried to refuse, preferring to direct negotiations from Paris, but Queen Catherine was insistent. Monluc departed Paris on 17 August, the day before the marriage of Henry of Navarre and Marguerite d'Angoulême. He was at S. Didier, where he had fallen ill with dysentery, when he heard the news of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre. He wrote immediately to the Court, demanding a full account of what had happened, knowing that he would have to answer many questions from hostile persons during his trip and during the negotiations in Poland. He was arrested at S. Mihiel in Lorraine and taken to prison in Verdun, under the suspicion that he was involved in the massacre. He wrote to Catherine de Medicis on 1 September, and shortly the King sent orders for his release. He was again detained in Frankfort by some disgruntled German Huguenot troops, complaining that they had never been paid. He finally arrived in Poland at the end of October, where he found widespread plague. The French Court, having heard of the horror caused by the massacre, and believing that Monluc needed help, sent Gilles de Noailles, brother of François de Noailles, former bishop of Dax, whose star had fallen along with that of Cardinal Odet de Chatillon. Monluc, fearing the loss of his own prestige, tried to refuse the help, but Noailles was sent anyway.

Negotiations were slow. There were several candidates, and the Polish nobility expected to be wooed and bribed from every direction. There were Protestant and Catholic interests at work. A quick election would cut short their game. They all affected to be shocked and scandalized by the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. Monluc gave two notable speeches (''harangues''), one before a plenary session of the Polish nobility on 10 April 1573, and the other before the Estates of Poland on 25 April, which contributed materially to the success of his diplomacy. Henry of Valois was elected King of Poland on 16 May 1573.

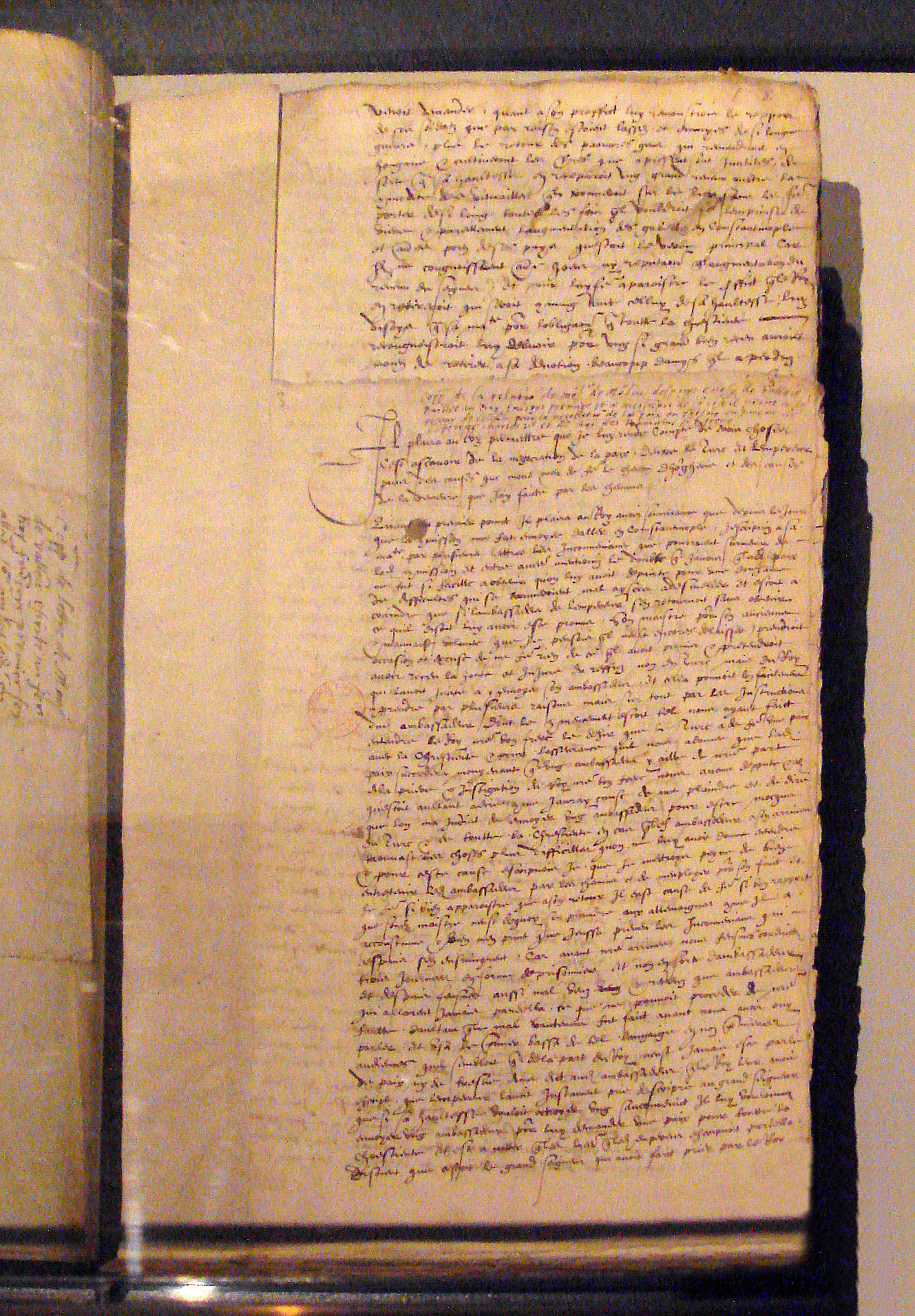

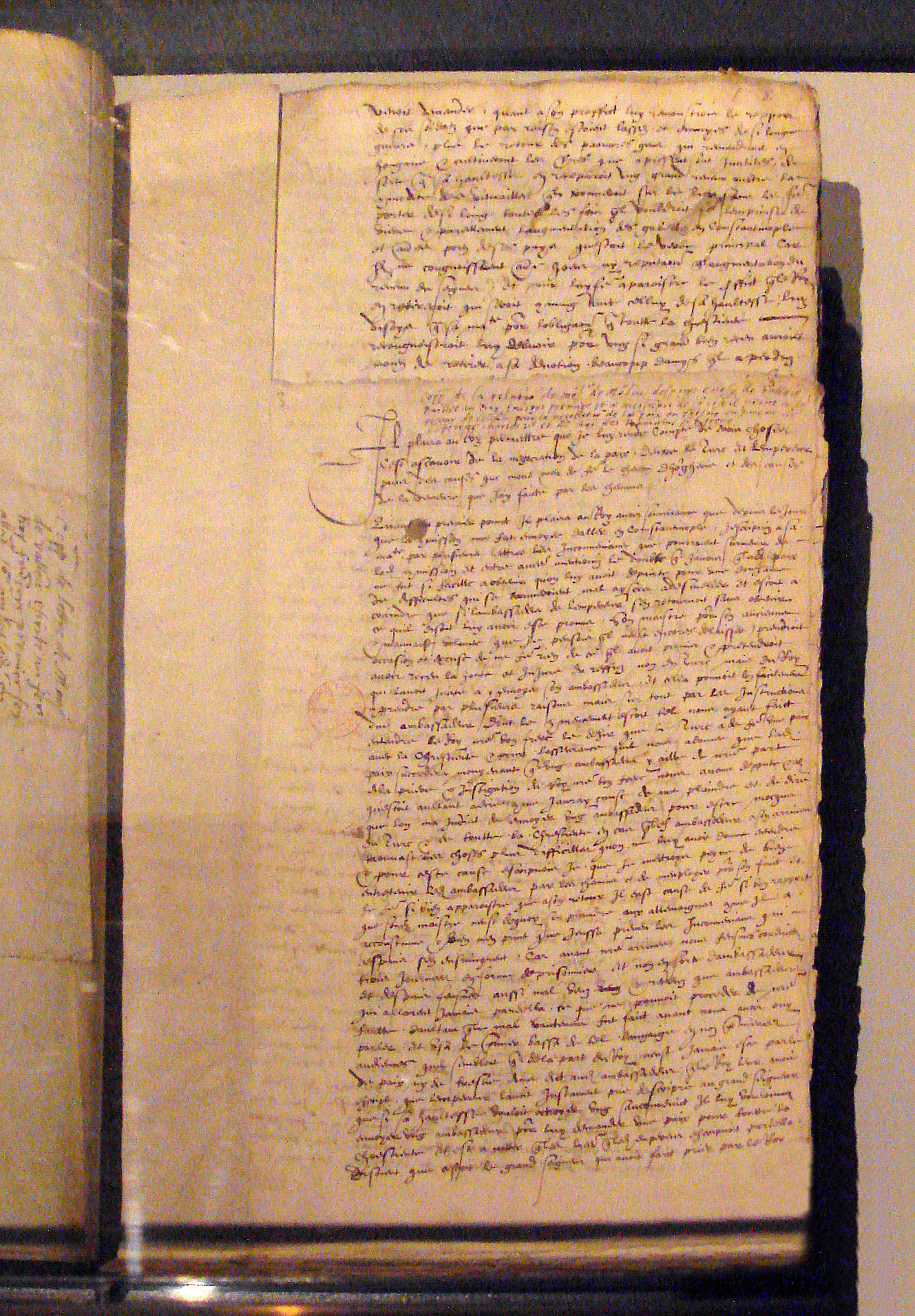

The Bishop of Valence later wrote his own narrative of his heroic efforts, ''Election du Roy Henry III, roy de Pologne, décrite par Jean de Monluc, Évêque de Valence'' (Paris 1574). The story was also told in the memoires of Monluc's secretary, Jean Choisnin (Paris 1789).

In 1576–1577, Jean de Monluc took part in the Estates of Blois. He spoke in December on the proposal to revoke the edict of pacification and resume the war against the Huguenots.

Death

In 1578, beginning on 12 April, a meeting of the Estates of Languedoc took place at Béziers, under the presidency of Abbot Pierre Dufaur the Vicar-General of Cardinal d'Armagnac, Archbishop of Toulouse. Bishop de Monluc participated and gave a speech. Jean de Monluc died on 13 April 1579 in Toulouse, where he had come to make a report to the Queen Mother. He had been reconciled to the Roman Catholic Church by a Jesuit. Bishop Jean de Monluc left a natural son,Jean de Montluc de Balagny

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* J ...

(d. 1603), seigneur

''Seigneur'' is an originally feudal title in France before the Revolution, in New France and British North America until 1854, and in the Channel Islands to this day. A seigneur refers to the person or collective who owned a ''seigneurie'' (or ...

de Balagny, who was at first a zealous member of the League

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

Sports

* Sports league

* Rugby league, full contact footba ...

, but later made his submission to Henry IV, and received from him the principality of Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

and, in 1594, the ''baton'' of a marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1 ...

.

References

Books and articles

* (Page 801 is the index page. Montluc is indexed under ''Valence, Bishop of'' which is how he is referred to within the Calendar). * * he Levant assignment, 1537* pologetic* * * bsolete* * * * * hoisnin's memoirs; the two harangues before the Polish Diet in 1573* *See also

* Jean de Montluc, Wikipedia-France *Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was o ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Monluc, Jean de

French male writers

1508 births

1579 deaths

Bishops of Condom

Bishops of Valence

Scottish Reformation

Ambassadors of France to Scotland

16th-century French Roman Catholic bishops

16th-century French diplomats

Bishops of Saint-Dié