James Tully (philosopher) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Hamilton Tully (; born 1946) is a Canadian philosopher who is the Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Law, Indigenous Governance and Philosophy at the

Cambridge University Press ''Ideas in Context'' Series

He first gained his reputation for his scholarship on the political philosophy of John Locke, and has written on constitutionalism, diversity, indigenous politics, recognition theory, multiculturalism, and imperialism. He was special advisor to the After completing his PhD at

After completing his PhD at

Tully's 1995, ''Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity'' engages with the famous indigenous sculpture ''

Tully's 1995, ''Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity'' engages with the famous indigenous sculpture ''

Pdf of the essay

* "Life Sustains Life 2: The ways of re-engagement with the living earth", in Akeel Bilgrami, ed. ''Nature and Value'' (Columbia University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Life Sustains Life 1: Value: Social and Ecological", in Akeel Bilgrami, ed. ''Nature and Value'' (Columbia University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Trust, Mistrust and Distrust in Diverse Societies", in Dimitri Karmis and François Rocher, eds. ''Trust and Distrust in Political Theory and Practice: The Case of Diverse Societies'' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Las luchas de los pueblos Indígenas por y de la libertad", in ''Descolonizar el Derecho. Pueblos Indígenas, Derechos Humanos y Estado Plurinacional'', eds. Roger Merino and Areli Valencia (Palestra: Lima, Perú, 2018), pp. 49–96.

Available online

* "Reconciliation Here on Earth", in Michael Asch, John Borrows & James Tully, eds., ''Reconciliation and Resurgence'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018). * "Deparochializing Political Theory and Beyond: A Dialogue Approach to Comparative Political Thought", ''Journal of World Philosophies'', 1.5 (Fall 2016), pp. 1–18.

Available online

* "Two Traditions of Human Rights," in Matthias Lutz-Bachmann and Amos Nascimento, eds., ''Human Rights, Human Dignity and Cosmopolitan Ideals'', (London: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 139–158. (Reprinted and revised from 2012 "Rethinking Human Rights and Enlightenment") * "Global Disorder and Two Responses", ''Journal of Intellectual History and Political Thought'', 2.1 (November 2013). * "Communication and Imperialism", in Arthur Kroker and Marilouise Kroker, eds., ''Critical Digital Studies A Reader'', Second Edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), pp. 257–283 (Reprint of 2008). * "Two Ways of Realizing Justice and Democracy: Linking Amartya Sen and Elinor Ostrom", ''Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy'', 16.2 (March 2013) 220–233. * "'Two Concepts of Liberty' in Context", ''Isaiah Berlin and the Politics of Freedom'', ed. Bruce Baum and Robert Nichols (London: Routledge, 2013), 23–52. * "On the Global Multiplicity of Public Spheres. The democratic transformation of the public sphere?"

Pdf of the essay

. This is the original, longer version of a piece previously published in Christian J. Emden and David Midgley, eds., ''Beyond Habermas: Democracy, Knowledge, and the Public Sphere'' (NY: Berghahn Books, 2013), pp. 169–204. * "Middle East Legal and Governmental Pluralism: A view of the field from the demos", ''Middle East Law and Governance'', 4 (2012), 225–263. * "Dialogue", in 'Feature Symposium: Reading James Tully, Public Philosophy in a New Key (Vols. I & II),’ ''Political Theory'', 39.1 (February 2011), 112–160, 145–160. * "Rethinking Human Rights and Enlightenment", in ''Self-evident Truths? Human Rights and the Enlightenment: The Oxford Amnesty Lectures of 2010'', ed. Kate Tunstall (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 3–35. (reprinted and revised as "Two Traditions of Human Rights," 2014). * "Conclusion: Consent, Hegemony, Dissent in Treaty Negotiations", in ''Consent Among Peoples'', ed. J. Webber and C. MacLeod (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010), 233–256. * "Lineages of Contemporary Imperialism", ''Lineages of Empire: The Historical Roots of British Imperial Thought'', ed. Duncan Kelly (Oxford: Oxford University Press and The British Academy, 2009), 3–30. * "The Crisis of Global Citizenship," ''Radical Politics Today'', July 2009.

PDF of the essay

* "Two Meanings of Global Citizenship: Modern and Diverse", in ''Global Citizenship Education: Philosophy, Theory and Pedagogy'', ed. M.A. Peters, A. Britton, H. Blee (Sense Publishers, 2008), 15–41. * "Modern Constitutional Democracy and Imperialism." ''Osgoode Hall Law Journal'' 46.3 (2008): 461–493. (Special issue on Comparative Constitutionalism & Transnational Law). * "Communication and Imperialism" in ''1000 Days of Theory'' (edited by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker), CTheory (2006). Reprinted in ''The Digital Studies Reader'', ed. A. & M. Kroker ( University of Toronto Press, 2008). Available: http://www.ctheory.net/printer.aspx?id=508. * "A New Kind of Europe? Democratic Integration in the European Union". Constitutionalism Web-Papers, 4 (2006). * "Wittgenstein and political philosophy: Understanding Practices of critical Reflection", in ''The Grammar of politics. Wittgenstein and Political Philosophy'', pp. 17–42. Ed. Cressida J. Heyes (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003). An earlier version appeared as "Wittgenstein and Political Philosophy: Understanding Practices of Critical Reflection," ''Political Theory'' 17, no.2 (1989):172–204, copyright @ 1989 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Video available

* "The Importance of the Study of Imperialism and Political Theory", ''Empire and Political Thought: A Retrospective'', with Dipesh Chakrabarty and Jeanne Morefield, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, The University of Chicago, 21 February 2019. * "Integral Nonviolence. Two Lawyers on Nonviolence: Mohandas K. Gandhi and Richard B. Gregg", The Center for Law and Society in a Global Context Annual Lecture, Queen Mary University, London, 22 October 2018.

Video available

* "On Gaia Citizenship", The Mastermind Lecture, University of Victoria, Victoria BC, Canada, 20 April 2016.

PDF available

* "On the Significance of Gandhi Today"

Perspectives on Gandhi’s Significance Workshop

Reed College, Portland OR, 16 April 2016.

audio available

PDF available

* "Richard Gregg and the Power of Nonviolence: The Power of Nonviolence as the unifying animacy of life"

Department of Philosophy, Colorado College, Colorado Springs CO, 1 March 2016. ( ttps://www.uvic.ca/socialsciences/politicalscience/assets/docs/faculty/tully/tully-richard-gregg.pdf PDF available * "A View of Transformative Reconciliation: Strange Multiplicity & the Spirit of Haida Gwaii at 20"

Indigenous Studies and Anti-Imperial Critique for the 21st Century: A symposium inspired by the legacies of James Tully

Yale University, 1–2 October 2015.

PDF available

* "Reflecting on Public Philosophy with Jim Tully", video interview by former students, Government House meditation garden, Victoria BC, March, 2015.

Video available

* "On Civic Freedom Today", The Encounter with James Tully, organized by

NOMIS workshop series: Nature and Value

Sheraton Park Lane Hotel, London UK, 22–23 June 2014. * "Civic Freedom in an Age of Diversity: James Tully’s Public Philosophy", Groupe de Recherche sur les sociétés plurinationales, Centre Pierre Péladeau, UQAM, Montréal, 24–26 April 2014.

Video available

* "Reconciliation Here on Earth: Shared Responsibilities", Ondaatje Hall, McCain Building, Dalhousie University, Department of Social Anthropology, College of Sustainability, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, 20 March 2014.

Video available

* "Life Sustains Life", th

Heyman Centre Series on Social and Ecological Value

with Jonathan Schell and Akeel Bilgrami, Columbia University, 2 May 2013. * "Citizenship for the love of the World," Department of Political Science, Cornell University, 14 March 2013. * "Transformative Change and Idle No More," Indigenous Peoples and Democratic Politics, First Peoples' House, University of British Columbia, 1 March 2013. * "Charles Taylor on Deep Diversity", The Conference on the Work of Charles Taylor, Museum of Fine Arts and University of Montreal, Montreal, 28–30 March 2012.

Video available

* "Citizenship for the Love of the World", Keynote Address, The Conference on Challenging Citizenship, Centro de Estudos Sociais, University of Coimbra, Coimbra Portugal, 2–5 June 2011. * "Diversity and Democracy after Franz Boas", The Stanley T. Woodward Keynote Lecture, Yale University, 15 September 2011, at the Symposium on Franz Boas. * "On Global Citizenship", The James A. Moffett 29 Lecture in Ethics, Centre for Human Values, Princeton University, 21 April 2011.

James Tully's webpage, University of Victoria

James Tully's PhilPeople / PhilPapers webpage

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tully, James 1946 births Alumni of the University of Cambridge Living people McGill University faculty Philosophy teachers Political science educators University of British Columbia alumni University of Toronto faculty University of Victoria faculty Scholars of nationalism Canadian philosophers Canadian political philosophers Historians of political thought Date of birth missing (living people) Place of birth missing (living people) Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada Indigenous studies in Canada

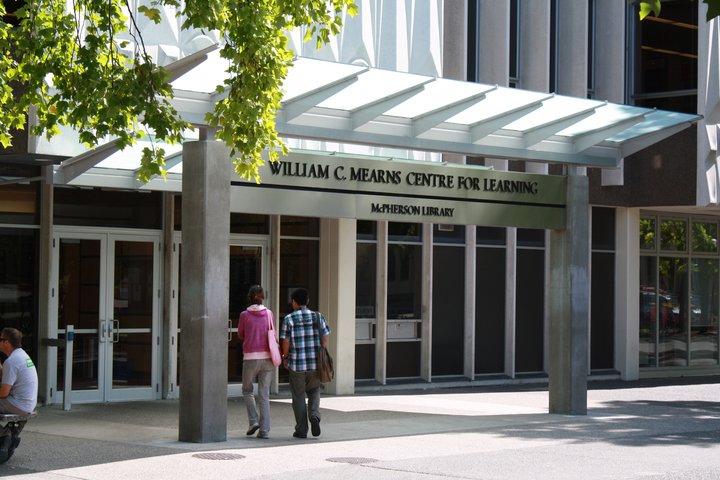

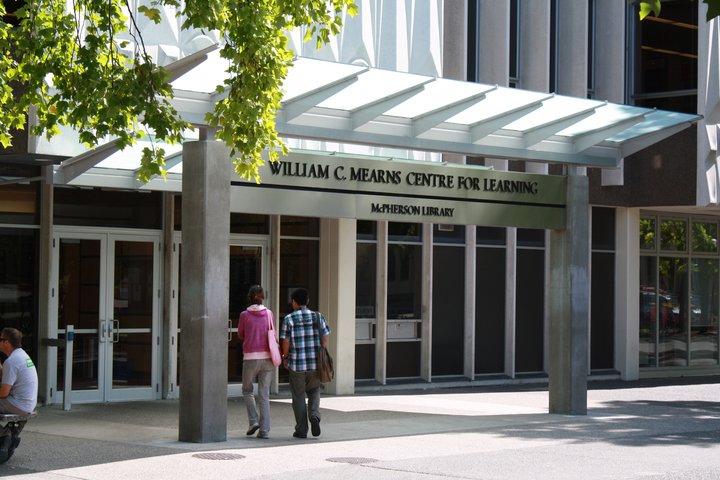

University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

, Canada. Tully is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and Emeritus Fellow of the Trudeau Foundation

The Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation (french: Fondation Pierre Elliott Trudeau), commonly called the Trudeau Foundation (french: Fondation Trudeau), is an independent and non-partisan Canadian charity founded in 2001 by friends and family of for ...

.

In May 2014, he was awarded the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

's David H. Turpin Award for Career Achievement in Research. In 2010, he was awarded the prestigious Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Prize

The Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Prize was established according to the will of Dorothy J. Killam to honour the memory of her husband Izaak Walton Killam.

Five Killam Prizes, each having a value of $100,000, are annually awarded by the Canada Cou ...

and the Thousand Waves Peacemaker Award in recognition of his distinguished career and exceptional contributions to Canadian scholarship and public life. Also in 2010, he was awarded the C. B. Macpherson Prize by the Canadian Political Science Association

The Canadian Political Science Association (french: Association canadienne de science politique) is an organization of political scientists in Canada. It is a bilingual organization and publishes the bilingual journal ''Canadian Journal of Politic ...

for the "best book in political theory written in English or French" in Canada 2008–10 for his 2008 two-volume ''Public Philosophy in a New Key.'' He completed his doctorate at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

in the United Kingdom and now teaches at the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

.

His research and teaching comprise a public philosophy

Public philosophy is a subfield of philosophy that involves engagement with the public. Jack Russell Weinstein defines public philosophy as "doing philosophy with general audiences in a non-academic setting".. It must be undertaken in a public ve ...

that is grounded in place (Canada) yet reaches out to the world of civic engagement with the problems of our time. He does this in ways that strive to contribute to dialogue between academics and citizens. For example, his research areas include the Canadian experience of coping with the deep diversity of multicultural and multinational citizenship; relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous people; and the emergence of citizenship of the living earth as the ground of sustainable futures.

Biography

James Tully was one of the four general editors of thCambridge University Press ''Ideas in Context'' Series

He first gained his reputation for his scholarship on the political philosophy of John Locke, and has written on constitutionalism, diversity, indigenous politics, recognition theory, multiculturalism, and imperialism. He was special advisor to the

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) was a Canadian royal commission established in 1991 with the aim of investigating the relationship between Indigenous peoples in Canada, the Government of Canada, and Canadian society as a whole. ...

(1991–1995). Over his career, Tully has held positions at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

, Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

, University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public university, public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park (Toronto), Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 ...

, and the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

.

After completing his PhD at

After completing his PhD at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

and his undergraduate degree at the University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a public research university with campuses near Vancouver and in Kelowna, British Columbia. Established in 1908, it is British Columbia's oldest university. The university ranks among the top thre ...

, he taught in the departments of Philosophy and Political Science at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

1977–1996. He was Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at the University of Victoria 1996–2001. In 2001–2003 he was the inaugural Henry N.R. Jackman Distinguished Professor in Philosophical Studies at the University of Toronto in the departments of Philosophy and Political Science, and in the Faculty of Law. Tully claims to have enjoyed his time at the University of Toronto, but preferred the open atmosphere and climate in British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

. He eventually returned to the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

in 2003, where he is now the Distinguished Professor of Political Science, Law, Indigenous Governance and Philosophy. Tully was influential in shaping the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria (UVic or Victoria) is a public research university located in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich, British Columbia, Canada. The university traces its roots to Victoria College, the first post-secondary insti ...

's Political Science department, which is renowned for its strong political theory program.

Political philosophy

Renewing and transforming public philosophy

Tully's approach to the study and teaching of politics is a form of historical and critical reflection on problems of political practice in the present. It is an attempt to renew and transform the tradition ofpublic philosophy

Public philosophy is a subfield of philosophy that involves engagement with the public. Jack Russell Weinstein defines public philosophy as "doing philosophy with general audiences in a non-academic setting".. It must be undertaken in a public ve ...

so it can effectively address the pressing political problems of our age in a genuinely democratic way. It does this by means of a dual dialogue of reciprocal and mutual learning among equals: between academics in different disciplines addressing the same problems (multidisciplinary); and between academics and citizens addressing the problems and struggles on the ground by their own ways of knowing and doing (democratic). The aim is to throw critical light on contemporary political problems by means of studies that free us to some extent from hegemonic ways of thinking and acting politically, enabling us to test their limits and to see and consider the concrete possibilities of thinking and acting differently.

The politics of cultural recognition

Tully's 1995, ''Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity'' engages with the famous indigenous sculpture ''

Tully's 1995, ''Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity'' engages with the famous indigenous sculpture ''Spirit of Haida Gwaii

The ''Spirit of Haida Gwaii'' is a sculpture by British Columbia Haida artist Bill Reid (1920–1998). There are two versions of it: the black canoe and the jade canoe. The black canoe features on Canadian $20 bills of the Canadian Journey serie ...

'' by Bill Reid

William Ronald Reid Jr. (12 January 1920 – 13 March 1998) (Haida) was a Canadian artist whose works include jewelry, sculpture, screen-printing, and paintings. Producing over one thousand original works during his fifty-year career, Reid ...

as a metaphor for the kind of democratic constitutionalism that can help reconcile the competing claims of multicultural and multinational societies. The 'strange multiplicity' of cultural diversity is embodied in the varied and assorted canoe passengers "squabbling and vying for recognition and position." There is no universal constitutional order imposed from above nor a single category of citizenship, because identities and relations change over time. This view rejects the "mythic unity of the community" imagined "in liberal and nationalist constitutionalism."

Tully argues that the concept of 'culture' is more flexible and constructive for thinking about the rival claims of political groups than the more rigid and exclusive concept 'nation.' Culture more readily suggests that group identities are plural, overlapping, and changing over time in their encounters with others. Unlike nationalism, the politics of cultural recognition does not assume that every group aspires to its own culturally homogenous 'nation-state.' Rather, cultures must find ways to share spaces and co-exist. While they may always strive to determine their own identities and relations, pursuant to "self rule, the oldest political good in the world," the solution is not to crack down on diversity or to impose one cultural model over others.

The solution is to broaden opportunities for participation and contestation, to further democratize institutions and relations of governance, including foundational constitutions. According to Tully, "a constitution should not be seen as a fixed set of rules but, rather, as an imperfect form of accommodation of the diverse members of a political association that is always open to negotiation by the members of the association."A major theme of Tully's work is a careful reconceptualization or clarification of a series of contested terms, including the notions of constitution, freedom, citizenship, and the adjectives democratic, civic, and global. Tully "re-describes" each to emphasize not static categories or abstract, transcendental or universal qualities, but rather practice or praxis – dialogical relations, action, and contestation. For more on Tully’s methodological approach, drawing heavily on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

, the Cambridge School of thought, and Michel Foucault, see Tully, ''Public Philosophy I'', pp. 4–5, 10, 15–131, ''Public Philosophy II'', pp. 254–256; see also David Owen, "Series Editor’s Foreword," in James Tully, ''On Global Citizenship: James Tully in Dialogue'' (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. ix–x, Robert Nichols and Jakeet Singh, "Editors' Introduction," ''Freedom and Democracy in an Imperial Context: Dialogues with James Tully'' (London: Routledge, 2014), pp. 1–3. No aspect of relations should be off limits to deliberation if called into question by participants affected by those relations. This is what Tully means by "democratic constitutionalism" as opposed to more conventional "constitutional democracy."Tully, ''Public Philosophy I'', p. 4. From this perspective, Tully can claim that " e constitution is thus one area of modern politics that has not been democratised over the last three hundred years."

For Tully, ''The Spirit of Haida Gwaii'' prefigures a more democratic, pluralistic, and just society. It evokes a simpler, more elegant, and sustainable ethos of gift-reciprocity in all our relationships, human and non-human. Getting along may be messy and imperfect business, but the passengers continue to row cooperatively, and the canoe of society glides onward.

Practices of civic freedom and global citizenship

In ''Public Philosophy in a New Key, Volume I: Democracy and Civic Freedom'', and ''Volume II: Imperialism and Civic Freedom'' (2008), Tully expands his approach "to a broader range of contemporary struggles: over diverse forms of recognition, social justice, the environment and imperialism." The two volumes mark a shift toward a principal emphasis on freedom. "The primary question," Tully writes, "is thus not recognition, identity or difference, but freedom; the freedom of the members of an open society to change the constitutional rules of mutual recognition and association from time to time as their identities change." This is "civic freedom," referring to the capacity people have to participate in the constitution of their own governance relations. To the extent that governance relations restrict this basic freedom, "they constitute a structure of domination, the members are not self-determining, and the society is unfree." Conditions of oppression, however, do not rule out or discount practices of civic freedom. Tully's public philosophy is not concerned with ideal conditions or hoped-for peaceful futures. Rather, civic freedom exists in conduct and in relations in the "here and now," not least under conditions of oppression and conflict. Against violence and tyranny, Tully argues, practices of civic freedom make the best "strategies of confrontation," because they generate conditions for transformative change. The concluding chapter of ''Public Philosophy in a New Key, Vol. II'' examines "the democratic means to challenge and transform imperial relationships ndbrings together the three themes of the two volumes: public philosophy, practices of civic freedom and the countless ways they work together to negotiate and transform oppressive relationships." Tully's civics-based approach offers a new way of thinking about a diverse array of contemporary and historical traditions of democratic struggle, including environmental movements and indigenous struggle. Tully summarizes the approach and its potential:'Practices of civic freedom' comprise the vast repertoire of ways of citizens acting together on the field of governance relationships and against the oppressive and unjust dimensions of them. These range from ways of 'acting otherwise' within the space of governance relationships to contesting, negotiating, confronting and seeking to transform them. The general aim of these diverse civic activities is to bring oppressive and unjust governance relationships under the on-going shared authority of the citizenry subject to them; namely, to civicise and democratize them from below.From this perspective, these kinds of powerful, civic movements are not deviations or anomalies to be corrected or appeased through discipline or cooptation, but exemplars of civic freedom. They disclose their positions or grievances not only through words and stated goals but through the very world they bring into being by their actions: civic "activists ''have to be the change'' that they wish to bring about." "Underlying this way of democratization," Tully argues, "is the Gandhian premise that democracy and peace can be brought about only by democratic and peaceful means." However, this is no utopian vision, according to Tully, referring to the "thousands" and "millions of examples of civic" practices everyday that make another world not only possible but "''actual''." To clarify and reinforce this approach, Tully argues for an expanded conception of the term ''citizenship'' to encompass all forms of governance-related conduct, with an emphasis on "negotiated practices."Tully, ''Public Philosophy II'', p. 248. ''Civic'' or ''global'' citizenship refers to the myriad of relations and practices (global and local) people find themselves embedded and participating in. The term ''global'' draws attention to the diverse and overlapping character of governance – and hence citizen – relations. Modes of civic and global citizenship "are the means by which cooperative practices of self-government can be brought into being and the means by which unjust practices of governance can be challenged, reformed and transformed by those who suffer under them." Tully carefully distinguishes his expanded notion of citizenship (diverse, cooperative, civic, global) from the narrower but more conventional notion of citizenship, which he calls "civil citizenship" (modern, institutional, and international). Where ''civic'' denotes practice and pluralism, ''civil'' citizenship singularly refers to "a status given by the institutions of the modern constitutional state in international law." This kind of (civil) citizenship is associated with the dominant tradition of liberalism, in which the state ensures a free market, a set of negative liberties (especially protections against state infringements into the private sphere), and a narrow range of participation through institutions of free speech and representative government. Tully argues that this dominant module of civil citizenship is neither universal nor inevitable; rather, it is "one singular, historical form of citizenship among others." More problematically, the civil tradition often plays handmaiden to empire, insofar as imperial powers operate under international banners of 'progress' and 'liberalism':

the dominant forms of representative democracy, self-determination and democratisation promoted through international law are not alternatives to imperialism, but, rather, the means through which informal imperialism operates against the wishes of the majority of the population of the post-colonial world.By contextualizing and de-centering, or "provincializing," modern categories of "allegedly universal" citizenship, Tully aims to broaden and democratize the field of citizenship and citizen practices. "This ivic and globalmode of citizenship," he argues, "has the capacity to overcome the imperialism of the present age and bring a democratic world into being." More recently, Tully has emphasized the importance of "coordinating" the different ways that civil (deliberative) and civic (cooperative) citizens address the same political problems, such as social and ecological justice.

The transformative power of nonviolence

In the closing pages of ''Public Philosophy in a New Key, Vol. II'', Tully explicitly links his work to the study and practice of nonviolence. He identifies four main components ofMahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

's life practice of Satyagraha that offer a model for approaching civic freedom and global citizenship practices: 1) noncooperation with unjust institutions, 2) a commitment to nonviolent means of resistance, 3) a focus on local, community-based modes of self-reliance and self-governance, and 4), as a precursor to these three components, "personal practices of self-awareness and self-formation." According to Tully, these cornerstones of nonviolent power "are daily practices of becoming an exemplary citizen."

Tully has since focused increasingly on the study and practice nonviolent ethics and nonviolent resistance. For example, he writes,

the alternative of a politics of reasonable nonviolent cooperation and agonistics (Satyagraha) was discovered in the twentieth century byA major overlap between Tully's civic freedom and the study of nonviolence is the shared emphasis on practice, on methods, on means rather than on ends. "For cooperative citizens," Tully writes, "means and ends are internally related, like a seed to the full-grown plant, as Gandhi put it."Tully, ''On Global Citizenship'', p. 96. This is because means "are pre-figurative or constitutive of ends. Consequently, democratic and peaceful relationships among humans are brought about by democratic and non-violent means." Tully repudiates the "depressing history" of "self-defeating violent means." He rejects the idea, prevalent across the spectrum of Western political thought, from revolutionaries to reactionaries (the "reigning dogma of the left and right") that peaceful and democratic societies can be brought about by coercive and violent means. Rather, according to Tully, "the means of violence and command relationships do not bring about peace and democracy. They too are constitutive means. They bring aboutWilliam James William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States. James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...,Gandhi Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ..., Abdul Gaffar Khan, Einstein,Ashley Montagu Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu (June 28, 1905November 26, 1999) — born Israel Ehrenberg — was a British-American anthropologist who popularized the study of topics such as race and gender and their relation to politics and development. He ...,Bertrand Russell Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ..., Martin Luther King Junior, Thomas Merton,Thich Nhat Hanh Thích is a name that Vietnamese monks and nuns take as their Buddhist surname to show affinity with the Buddha. Notable Vietnamese monks with the name include: * Thích Huyền Quang (1919–2008), dissident and activist * Thích Quảng Độ ( ...,Gene Sharp Gene Sharp (January 21, 1928 – January 28, 2018) was an American political scientist. He was the founder of the Albert Einstein Institution, a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the study of nonviolent action, and professor of pol ...,Petra Kelly Petra Karin Kelly (29 November 1947 – 1 October 1992) was a German Green politician and ecofeminist activist. She was a founding member of the German Green Party, the first Green party to rise to prominence both nationally in Germany and wo ..., Johan Galtung and Barbara Deming. They argued that the antagonistic premise of western theories of reasonable violence is false. Nonviolent practices of cooperation, disputation and dispute resolution are more basic and prevalent than violent antagonism. This is a central feature of civic freedom.

security dilemma

In international relations, the security dilemma (also referred to as the spiral model) is when the increase in one state's security (such as increasing its military strength) leads other states to fear for their own security (because they do not k ...

s and the spiral of the command relations necessary for war preparation, arms races and more violence."

For these reasons, Tully extends his civics-based public philosophy to "practitioners and social scientists hoare beginning to appreciate the transformative power of participatory non-violence and the futility of war in comparison."

Sustainability and Gaia citizenship

Tully's approach to nonviolent citizenship practices includes relations with the non-human world. Tully argues that Homo Sapiens should see themselves as interdependent civic citizens of the ecological relationships in which they live and breathe and have their being. As such, they have responsibilities to care for and sustain these relationships that, in reciprocity, sustain them and all the other life forms that are interdependent on them. Tully's " Gaia citizenship" draws on earth sciences and life sciences as well as indigenous traditions. For example, pointing to the work of ecological scientists from Aldo Leopold,Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist whose influential book '' Silent Spring'' (1962) and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental ...

, and Barry Commoner

Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the director of the ...

to the Intergovernmental Panels on Climate Change, Tully links the unsustainability crisis of the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene ( ) is a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change.

, neither the International Commissio ...

to his own critique of "modern civil" modes of governmentality (as violent, exploitative, and destructive). Likewise, he points to Indigenous knowledge that conceptualizes human interconnectedness with the earth as gift-reciprocity relationships and as a model for social relationships. The famous Indigenous artwork ''Spirit of Haida Gwaii'' remains exemplary of democratic and pluralistic ways of thinking and acting – between humans and the natural environments on which they depend.

Tully's argument is that his account of interdependent agents in relationships of governance and situated freedom can be extended with modifications to describe human situatedness in ecological relationships – as either giving rise to 'virtuous' or 'vicious cycles', depending on how we act in and on them."Whether the partners generate trustful and peaceful relationships through virtuous cycles of reciprocal interaction or distrustful and aggressive relationships through vicious cycles of antagonism depends in part on whether they become aware of this interweaving of their identities in the course of their interactions or whether they hold fast to atomism: the false belief that their individual and collective identities exist prior to and independent of encounter and interaction," Tully, "Trust in Diverse Societies," forthcoming. And "The aim is to work together to transform unsustainable relationships into conciliatory and sustainable ones: that is, to transform a vicious social system into a virtuous social system that sustains the ways of life of all affected," Tully, "Reconciliation Here on Earth," forthcoming.

Selected publications

Single-authored books

* ''Public Philosophy in a New Key, Volume I: Democracy and Civic Freedom'' (Cambridge University Press, 2008), . * ''Public Philosophy in a New Key, Volume II: Imperialism and Civic Freedom'' (Cambridge University Press, 2008), . * ''Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity'', Cambridge University Press, 1995, . * ''An Approach To Political Philosophy: Locke in Contexts'' (Cambridge University Press, 1993) . * ''A Discourse on Property: John Locke and his Adversaries'' (Cambridge University Press, 1980) .Dialogues with James Tully

* ''Civic Freedom in an Age of Diversity: The Public Philosophy of James Tully'', Edited by Dimitri Karmis and Jocelyn Maclure (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2019, forthcoming) * ''Freedom and Democracy in an Imperial Context, Dialogues with James Tully'', Edited by Robert Nichols, Jakeet Singh (Routledge, 2014) . This text contains eleven chapters by various authors and Tully's responses to them. * ''On Global Citizenship: Dialogue with James Tully,'' Critical Powers Series (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), . This text includes "On Global Citizenship" (a reprint of the concluding chapter of ''Public Philosophy in a New Key Vol. II'' plus a new "Afterword – The crisis of global citizenship: Civil and civic responses"), seven chapters by other authors on Tully's work, and finally Tully's "Replies".Books edited

* (Editor) Richard Bartlett Gregg, ''The Power of Nonviolence'' (Cambridge University Press, October 2018) * (Co-editor with Michael Asch and John Borrows) ''Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings'' (University of Toronto Press, 2018) . * (Co-editor with Annabel Brett) ''Rethinking the foundations of modern political thought'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006) . * (Co-editor with Alain-G. Gagnon) ''Multinational Democracies'' (Cambridge University Press, 2001) . * (Editor) ''Philosophy in an Age of Pluralism. The Philosophy of Charles Taylor in Question'' (Cambridge University Press, 1994) . * (Editor) Samuel Pufendorf, '' On the Duty of Man and Citizen according to Natural Law'' (Cambridge University Press, 1991) . * (Editor) ''Meaning and Context: Quentin Skinner and his Critics'' (Polity Press and Princeton University Press, 1988) . * (Editor) John Locke, ''A Letter Concerning Toleration'' (Hackett, 1983) .Recent articles and chapters

* "The Power of Integral Nonviolence: On the Significance of Gandhi Today", ''Politika'', April 2019Pdf of the essay

* "Life Sustains Life 2: The ways of re-engagement with the living earth", in Akeel Bilgrami, ed. ''Nature and Value'' (Columbia University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Life Sustains Life 1: Value: Social and Ecological", in Akeel Bilgrami, ed. ''Nature and Value'' (Columbia University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Trust, Mistrust and Distrust in Diverse Societies", in Dimitri Karmis and François Rocher, eds. ''Trust and Distrust in Political Theory and Practice: The Case of Diverse Societies'' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2019) forthcoming. * "Las luchas de los pueblos Indígenas por y de la libertad", in ''Descolonizar el Derecho. Pueblos Indígenas, Derechos Humanos y Estado Plurinacional'', eds. Roger Merino and Areli Valencia (Palestra: Lima, Perú, 2018), pp. 49–96.

Available online

* "Reconciliation Here on Earth", in Michael Asch, John Borrows & James Tully, eds., ''Reconciliation and Resurgence'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018). * "Deparochializing Political Theory and Beyond: A Dialogue Approach to Comparative Political Thought", ''Journal of World Philosophies'', 1.5 (Fall 2016), pp. 1–18.

Available online

* "Two Traditions of Human Rights," in Matthias Lutz-Bachmann and Amos Nascimento, eds., ''Human Rights, Human Dignity and Cosmopolitan Ideals'', (London: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 139–158. (Reprinted and revised from 2012 "Rethinking Human Rights and Enlightenment") * "Global Disorder and Two Responses", ''Journal of Intellectual History and Political Thought'', 2.1 (November 2013). * "Communication and Imperialism", in Arthur Kroker and Marilouise Kroker, eds., ''Critical Digital Studies A Reader'', Second Edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), pp. 257–283 (Reprint of 2008). * "Two Ways of Realizing Justice and Democracy: Linking Amartya Sen and Elinor Ostrom", ''Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy'', 16.2 (March 2013) 220–233. * "'Two Concepts of Liberty' in Context", ''Isaiah Berlin and the Politics of Freedom'', ed. Bruce Baum and Robert Nichols (London: Routledge, 2013), 23–52. * "On the Global Multiplicity of Public Spheres. The democratic transformation of the public sphere?"

Pdf of the essay

. This is the original, longer version of a piece previously published in Christian J. Emden and David Midgley, eds., ''Beyond Habermas: Democracy, Knowledge, and the Public Sphere'' (NY: Berghahn Books, 2013), pp. 169–204. * "Middle East Legal and Governmental Pluralism: A view of the field from the demos", ''Middle East Law and Governance'', 4 (2012), 225–263. * "Dialogue", in 'Feature Symposium: Reading James Tully, Public Philosophy in a New Key (Vols. I & II),’ ''Political Theory'', 39.1 (February 2011), 112–160, 145–160. * "Rethinking Human Rights and Enlightenment", in ''Self-evident Truths? Human Rights and the Enlightenment: The Oxford Amnesty Lectures of 2010'', ed. Kate Tunstall (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 3–35. (reprinted and revised as "Two Traditions of Human Rights," 2014). * "Conclusion: Consent, Hegemony, Dissent in Treaty Negotiations", in ''Consent Among Peoples'', ed. J. Webber and C. MacLeod (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010), 233–256. * "Lineages of Contemporary Imperialism", ''Lineages of Empire: The Historical Roots of British Imperial Thought'', ed. Duncan Kelly (Oxford: Oxford University Press and The British Academy, 2009), 3–30. * "The Crisis of Global Citizenship," ''Radical Politics Today'', July 2009.

PDF of the essay

* "Two Meanings of Global Citizenship: Modern and Diverse", in ''Global Citizenship Education: Philosophy, Theory and Pedagogy'', ed. M.A. Peters, A. Britton, H. Blee (Sense Publishers, 2008), 15–41. * "Modern Constitutional Democracy and Imperialism." ''Osgoode Hall Law Journal'' 46.3 (2008): 461–493. (Special issue on Comparative Constitutionalism & Transnational Law). * "Communication and Imperialism" in ''1000 Days of Theory'' (edited by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker), CTheory (2006). Reprinted in ''The Digital Studies Reader'', ed. A. & M. Kroker ( University of Toronto Press, 2008). Available: http://www.ctheory.net/printer.aspx?id=508. * "A New Kind of Europe? Democratic Integration in the European Union". Constitutionalism Web-Papers, 4 (2006). * "Wittgenstein and political philosophy: Understanding Practices of critical Reflection", in ''The Grammar of politics. Wittgenstein and Political Philosophy'', pp. 17–42. Ed. Cressida J. Heyes (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003). An earlier version appeared as "Wittgenstein and Political Philosophy: Understanding Practices of Critical Reflection," ''Political Theory'' 17, no.2 (1989):172–204, copyright @ 1989 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Recent public talks

* "Crises of Democracy", Dialogue with Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Global Politics in Critical Perspectives – Transatlantic Dialogues, 15 March 2019.Video available

* "The Importance of the Study of Imperialism and Political Theory", ''Empire and Political Thought: A Retrospective'', with Dipesh Chakrabarty and Jeanne Morefield, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, The University of Chicago, 21 February 2019. * "Integral Nonviolence. Two Lawyers on Nonviolence: Mohandas K. Gandhi and Richard B. Gregg", The Center for Law and Society in a Global Context Annual Lecture, Queen Mary University, London, 22 October 2018.

Video available

* "On Gaia Citizenship", The Mastermind Lecture, University of Victoria, Victoria BC, Canada, 20 April 2016.

PDF available

* "On the Significance of Gandhi Today"

Perspectives on Gandhi’s Significance Workshop

Reed College, Portland OR, 16 April 2016.

audio available

PDF available

* "Richard Gregg and the Power of Nonviolence: The Power of Nonviolence as the unifying animacy of life"

Department of Philosophy, Colorado College, Colorado Springs CO, 1 March 2016. ( ttps://www.uvic.ca/socialsciences/politicalscience/assets/docs/faculty/tully/tully-richard-gregg.pdf PDF available * "A View of Transformative Reconciliation: Strange Multiplicity & the Spirit of Haida Gwaii at 20"

Indigenous Studies and Anti-Imperial Critique for the 21st Century: A symposium inspired by the legacies of James Tully

Yale University, 1–2 October 2015.

PDF available

* "Reflecting on Public Philosophy with Jim Tully", video interview by former students, Government House meditation garden, Victoria BC, March, 2015.

Video available

* "On Civic Freedom Today", The Encounter with James Tully, organized by

Chantal Mouffe

Chantal Mouffe (; born 17 June 1943) is a Belgian political theorist, formerly teaching at University of Westminster.

She is best known for her contribution to the development—jointly with Ernesto Laclau, with whom she co-authored her most fre ...

, Centre for the Study of Democracy, University of Westminster, London, UK, 24 June 2014.

* "Thoughts on Co-Sustainability"NOMIS workshop series: Nature and Value

Sheraton Park Lane Hotel, London UK, 22–23 June 2014. * "Civic Freedom in an Age of Diversity: James Tully’s Public Philosophy", Groupe de Recherche sur les sociétés plurinationales, Centre Pierre Péladeau, UQAM, Montréal, 24–26 April 2014.

Video available

* "Reconciliation Here on Earth: Shared Responsibilities", Ondaatje Hall, McCain Building, Dalhousie University, Department of Social Anthropology, College of Sustainability, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, 20 March 2014.

Video available

* "Life Sustains Life", th

Heyman Centre Series on Social and Ecological Value

with Jonathan Schell and Akeel Bilgrami, Columbia University, 2 May 2013. * "Citizenship for the love of the World," Department of Political Science, Cornell University, 14 March 2013. * "Transformative Change and Idle No More," Indigenous Peoples and Democratic Politics, First Peoples' House, University of British Columbia, 1 March 2013. * "Charles Taylor on Deep Diversity", The Conference on the Work of Charles Taylor, Museum of Fine Arts and University of Montreal, Montreal, 28–30 March 2012.

Video available

* "Citizenship for the Love of the World", Keynote Address, The Conference on Challenging Citizenship, Centro de Estudos Sociais, University of Coimbra, Coimbra Portugal, 2–5 June 2011. * "Diversity and Democracy after Franz Boas", The Stanley T. Woodward Keynote Lecture, Yale University, 15 September 2011, at the Symposium on Franz Boas. * "On Global Citizenship", The James A. Moffett 29 Lecture in Ethics, Centre for Human Values, Princeton University, 21 April 2011.

References

Further reading

* *External links

James Tully's webpage, University of Victoria

James Tully's PhilPeople / PhilPapers webpage

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tully, James 1946 births Alumni of the University of Cambridge Living people McGill University faculty Philosophy teachers Political science educators University of British Columbia alumni University of Toronto faculty University of Victoria faculty Scholars of nationalism Canadian philosophers Canadian political philosophers Historians of political thought Date of birth missing (living people) Place of birth missing (living people) Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada Indigenous studies in Canada