James Hutchison Stirling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

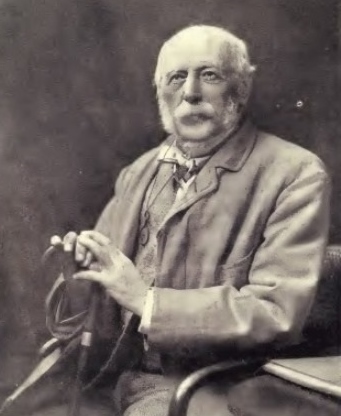

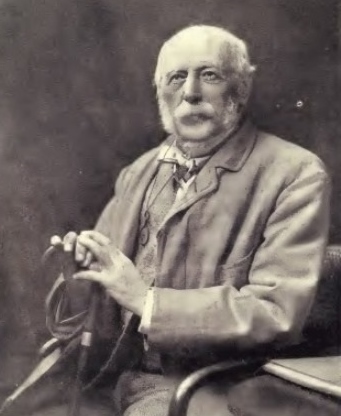

James Hutchison Stirling (22 June 1820 – 19 March 1909) was a Scottish idealist

James Hutchison Stirling (22 June 1820 – 19 March 1909) was a Scottish idealist

James Hutchison Stirling was born in

James Hutchison Stirling was born in

Darwinianism: workmen and work

' (1894) – In this work Stirling recollects views on

James Hutchison Stirling: His Life and Work

by Amelia Hutchison Stirling (1912) {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, James Hutchison 1820 births 1909 deaths 19th-century British philosophers 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Hegelian philosophers Non-Darwinian evolution Scottish philosophers

James Hutchison Stirling (22 June 1820 – 19 March 1909) was a Scottish idealist

James Hutchison Stirling (22 June 1820 – 19 March 1909) was a Scottish idealist philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and physician. His work '' The Secret of Hegel'' (1st edition, 1865, in 2 vols.; revised edition, 1898, in 1 vol.) gave great impetus to the study of Hegelian philosophy both in Britain and in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, and it was also accepted as an authoritative work on Hegel's philosophy in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The book helped to create the philosophical movement known as British idealism.

Biography

James Hutchison Stirling was born in

James Hutchison Stirling was born in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Scotland, the fifth son (and the youngest of six children) of William Stirling (died 14 March 1851) and Elizabeth Christie (d. 1828). William was a wealthy textile manufacturer who was a partner in the Glasgow firm of James Hutchison & Co., which manufactured muslin (lightweight cotton cloth in a plain weave, used for making sheets and for a variety of other purposes). William was known for his deeply-held religious views, many of which strongly influenced his son James.

Stirling studied at Young's Academy in Glasgow, followed by nine years of education (1833–1842) at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, where he studied medicine, history, and classics. He became a Licentiate (1842, medical diploma) and Fellow (1860) of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

.

Stirling married Jane Hunter Mair (died 5 July 1903), an old family friend, on 28 April 1847 in Irvine, North Ayrshire

Irvine ( ; sco, Irvin,

gd, Irbhinn, IPA: Scotland Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. The couple had seven children (five daughters and two sons), as follows: Jessie Jane Stirling (born 26 June 1850) (who married Rev. Robert Armstrong of Glasgow), Elizabeth Margaret Stirling (11 February 1852 – 1871), Amelia Hutchison Stirling, Florence Hutchison Stirling (1858 – 6 May 1948), Lucy Stirling, William Stirling, and David Stirling. Stirling's daughter Amelia wrote many books on historical subjects, and she was the joint-translatorwith William Hale White (1831–1913)of Spinoza's ''Ethics'' (1883). She also wrote a biography of her father James titled ''James Hutchison Stirling: His Life and Work'' (London and Leipzig: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912). Stirling's daughter Florence won the Scottish Ladies' Championship in chess five times (in 1905, 1906, 1907, 1912, and 1913).

After receiving a large inheritance from his father's estate in 1851, Stirling left his medical practice. He then set out to learn French and German, for the purpose of being able to better understand continental philosophical trends. In pursuit of this goal, he moved his family briefly to gd, Irbhinn, IPA: Scotland Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Department ...

, France (located in the current Pas-de-Calais

Pas-de-Calais (, "strait of Calais"; pcd, Pas-Calés; also nl, Nauw van Kales) is a department in northern France named after the French designation of the Strait of Dover, which it borders. It has the most communes of all the departments of ...

department of the Hauts-de-France

Hauts-de-France (; pcd, Heuts-d'Franche; , also ''Upper France'') is the northernmost region of France, created by the territorial reform of French regions in 2014, from a merger of Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Picardy. Its prefecture is Lille. The ...

region), then to Paris for 18 months, then to St. Servan (located two miles from the ferry port of St. Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the All ...

in the Ille-et-Vilaine

Ille-et-Vilaine (; br, Il-ha-Gwilen) is a department of France, located in the region of Brittany in the northwest of the country. It is named after the two rivers of the Ille and the Vilaine. It had a population of 1,079,498 in 2019.

department of the Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

region of France) for four and a half years, and then finally to Heidelberg, Germany. In November 1857, Stirling and his family took up residence in London (at 3 Wilton Terrace, Kensington), where they lived for about three years. After this, in 1860 Stirling returned to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

his address there was 4 Laverockbank Road, Trinity, EdinburghEdinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory, 1908-9which then became his permanent residence until the end of his life, and where he wrote on the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

(1770–1831) and many other subjects. The primary result of his comprehensive Hegel studies was his influential work ''The Secret of Hegel'' (2 vols., 1865).

One of Stirling's other major philosophical works''Philosophy and Theology'' (1890) (consisting of his 20 Gifford Lectures, delivered at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

in 1889–1890)focuses not on Hegelian philosophical topics, but on Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's evolutionary theories.

Frederick Copleston

Frederick Charles Copleston (10 April 1907 – 3 February 1994) was an English Roman Catholic Jesuit priest, philosopher, and historian of philosophy, best known for his influential multi-volume '' A History of Philosophy'' (1946–75).

...

(''A History of Philosophy'' vol. VII, p. 12) wrote: "we may be inclined to smile at J. H. Stirling's picture of Hegel as the great champion of Christianity".

Stirling died in Edinburgh and is buried in Warriston Cemetery on the north side of the city. His grave lies in the centre of the long, upper section north of the vaults, facing south onto an east–west path.

Selected publications

Other works: *''Sir William Hamilton'' (1865) *'' The Secret of Hegel'' (1865) *''Text-book to Kant'' (1881) *''Philosophy and Theology'' (1890) ( Gifford Lectures) *Darwinianism: workmen and work

' (1894) – In this work Stirling recollects views on

Darwin's theory of evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

, including that of Thomas Brown and others, stating: "it is the theory involved which it is also my endeavour, with all honour, to refute." Stirling states "it is not by any means necessary that an evolutionist should be also a Darwinian."

*''What is Thought? or the Problem of Philosophy'' (1900)

*''The Categories'' (1903).

More concerned with literature:

*''Jerrold, Tennyson, and Macaulay'' (1868)

*''Burns in Drama'' (1878)

*''Philosophy in the Poets'' (1885).

Notes

References

* ;Attribution *External links

* * *James Hutchison Stirling: His Life and Work

by Amelia Hutchison Stirling (1912) {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, James Hutchison 1820 births 1909 deaths 19th-century British philosophers 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Hegelian philosophers Non-Darwinian evolution Scottish philosophers