James Gibbs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was one of

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was one of

By 1743 Gibbs, who was fond of wine and food, was described as "corpulent". In June 1749 Gibbs set out for the

By 1743 Gibbs, who was fond of wine and food, was described as "corpulent". In June 1749 Gibbs set out for the

Other early designs include the house of

Other early designs include the house of

In 1723 Gibbs was appointed a governor of

In 1723 Gibbs was appointed a governor of

Gibbs worked at both

Gibbs worked at both

File:Radcliffe Camera, Oxford - Oct 2006.jpg, Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University

File:Radcliffe2ndlevel.jpg, Interior, Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University

File:Senate House, Cambridge facade.jpg,

File:1236753-St Mary le Strand.JPG, West front, St Mary le Strand

File:St Mary-le-Strand outside.jpg, East front, St Mary le Strand

File:St Mary le Strand Church, London, UK - Diliff.jpg, Interior looking east, St Mary le Strand

File:London - St Clement Danes - 140811 103211.jpg, Steeple, St Clement Danes

File:Saint Martin in the Fields-1.jpg, West front, St Martin-in-the-Fields

File:St Martin in the Fields, Trafalgar Square - West end - geograph.org.uk - 1000129.jpg, Interior looking west, St Martin-in-the-Fields

File:St Martin in the Fields, Trafalgar Square - Font - geograph.org.uk - 998584.jpg, The font, St Martin-in-the-Fields

File:St Peter's Church, Vere Street Dec 2016.jpg, St Peter Vere Street

File:Derby Cathedral Interior.jpg, The nave, Derby Cathedral

File:Witley Court Baroque Church Worcestershire.JPG, St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley

File:Great Witley Church.jpg, Looking east, St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley

File:Sir William Turner's Almshouses - geograph.org.uk - 894877.jpg, Chapel, Sir William Turner's Almshouses, Kirkleatham

File:St Cuthberts Kirkleatham.jpg, Mausoleum on right, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham

File:Kirkleatham Turner Mausoleum.jpg, Mausoleum, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham

File:St. Mary, Patshull - geograph.org.uk - 120401.jpg, South front, St Mary, Patshull

File:St Lawrence, Whitchurch Lane, Little Stanmore - Chandos mausoleum (geograph 2613885).jpg, Chandos mausoleum, St Lawrence, Little Stanmore

File:Colston's Monument, Bristol.jpg, Edward Colston's Monument, All Saints' Church, Bristol

File:Burlington House courtyard edited.jpg, Burlington House forecourt, showing Gibbs' wings and a colonnade

File:Burlington Housec. 1806-8.jpg, Burlington House, one of the colonnades

File:Parlour 11 Henrietta Street V A 2502.jpg, Drawing room from 11 Henrietta Street, now in V&A Museum

File:Sudbrook House - Petersham.jpg, Sudbrook House

File:Ditchleyfront2.jpg, Ditchley House

File:Cannons middlesex.jpg, Cannons House

File:Antony House 03.jpg, Antony House, Cornwall

File:Stowe, One of the Boycott Pavilions - geograph.org.uk - 152745.jpg, Eastern Boycott Pavilion, 1728, Stowe House, dome altered; it used to have a spire like the Turner Mausoleum

File:The Fane of Pastorial Poetry, Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 836595.jpg, The Fane of Pastoral Poetry, 1729, Stowe House

File:Stowe Park Palladian bridge.jpg, Palladian bridge, 1738, Stowe House, based on the bridge at

File:Adolphe Jean-Baptiste Bayot04.jpg, Orleans House, Gibbs' Octagon on the left

File:Orleans House, Twickenham - London. (14821954927).jpg, Octagon, Orleans House

File:Detail of the interior of the Octagon at Orleans House (5881354195).jpg, Interior of the Octagon, Orleans House

File:Wimpole Hall, near Royston, Cambridgeshire - geograph.org.uk - 682114.jpg, Wimpole Hall, Gibbs' Library on the right

File:Cmglee Wimpole Hall chapel.jpg, The Chapel, Wimpole Hall

File:Badminton House.jpg, Badminton House, north front as remodelled by Gibbs

,

James Gibbs

Twickenham Museum {{DEFAULTSORT:Gibbs, James 1682 births 1754 deaths 18th-century Scottish architects Alumni of the University of Aberdeen Architects from Aberdeen British architecture writers Scottish ecclesiastical architects Fellows of the Royal Society People educated at Aberdeen Grammar School Scottish Baroque architects Scottish Roman Catholics

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was one of

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was one of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

's most influential architects. Born in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), a ...

, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture is a highly decorative and theatrical style which appeared in Italy in the early 17th century and gradually spread across Europe. It was originally introduced by the Catholic Church, particularly by the Jesuits, as a means ...

and Georgian architecture

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1714 and 1830. It is named after the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover— George I, George II, Ge ...

heavily influenced by Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of ...

. Among his most important works are St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

(at Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

), the cylindrical, domed Radcliffe Camera at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and the Senate House at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Gibbs very privately was a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

and a Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

. Because of this and his age, he had a somewhat removed relation to the Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

movement which came to dominate English architecture during his career. The Palladians were largely Whigs, led by Lord Burlington and Colen Campbell

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

, a fellow Scot who developed a rivalry with Gibbs. Gibbs' professional Italian training under the Baroque master Carlo Fontana

Carlo Fontana (1634 or 1638–1714) was an Italian architect originating from today's Canton Ticino, who was in part responsible for the classicizing direction taken by Late Baroque Roman architecture.

Biography

There seems to be no proof tha ...

also set him uniquely apart from the Palladian school. However, despite being unfashionable, he gained a number of Tory patrons and clients, and became hugely influential through his published works, which became popular as pattern books for architecture. The naming of the Gibbs surround for doors and windows, which he certainly did not invent, testifies to this influence.

His architectural style did incorporate Palladian elements, as well as forms from Italian Baroque and Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

(1573–1652), but was most strongly influenced by the work of Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

(1632–1723), who was an early supporter of Gibbs. Overall, Gibbs was an individual who formed his own style independently of current fashions. Architectural historian John Summerson

Sir John Newenham Summerson (25 November 1904 – 10 November 1992) was one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century.

Early life

John Summerson was born at Barnstead, Coniscliffe Road, Darlington. His grandfather w ...

describes his work as the fulfilment of Wren's architectural ideas, which were not fully developed in his own buildings. Despite the influence of his books, Gibbs, as a stylistic outsider, had little effect on the later direction of British architecture, which saw the rise of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism ...

shortly after his death.

Biography

Background and education

Born on 23 December 1682 in Fittysmire,Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), a ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, a younger son of a Patrick Gibbs merchant and his second wife Ann née Gordon, the family was Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

; there was a half-brother William from the first marriage to Isabel née Farquhar.Friedman, p.2 He was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School

Aberdeen Grammar School is a state secondary school in Aberdeen, Scotland. It is one of thirteen secondary schools run by the Aberdeen City Council educational department.

It is the oldest school in the city and one of the oldest grammar school ...

and Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has acted as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. However, the building was constructed for and is on lon ...

.Friedman, p.4 After the death of his parents he went in 1700 to stay with relatives in Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former Provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

. He later travelled through Europe, visiting Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, France, Switzerland and Germany. Some time after he left for Rome travelling via France. On 12 October 1703 he registered as a student at The Scots College.Friedman, p.5 He would have been studying for the Catholic priesthood

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned (" ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers onl ...

but had second thoughts. By the end of 1704 he was studying architecture under Carlo Fontana

Carlo Fontana (1634 or 1638–1714) was an Italian architect originating from today's Canton Ticino, who was in part responsible for the classicizing direction taken by Late Baroque Roman architecture.

Biography

There seems to be no proof tha ...

; he was also taught by Pietro Francesco Garroli, professor of perspective at the Accademia di San Luca

The Accademia di San Luca (the "Academy of Saint Luke") is an Italian academy of artists in Rome. The establishment of the Accademia de i Pittori e Scultori di Roma was approved by papal brief in 1577, and in 1593 Federico Zuccari became its fir ...

.Friedman, p.7 While in Rome Gibbs met John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont

John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont, PC, FRS (12 July 16831 May 1748), known as Sir John Perceval, Bt, from 1691 to 1715, as The Lord Perceval from 1715 to 1722 and as The Viscount Perceval from 1722 to 1733, was an Anglo- Irish politician.

Ea ...

who attempted to persuade him to move to Ireland. He moved to London in November 1708; his return to Britain was probably due to the terminal illness of his half-brother William, who died before James reached Britain.

Career

Still intending to take up the offer of work in Ireland, he had been befriended by John Erskine, Earl of Mar, while abroad. The Earl persuaded Gibbs to remain in London, offering him his first commission, alterations to his house inWhitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

. Around this time he met Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer

Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer (2 June 1689 – 16 June 1741), styled Lord Harley between 1711 and 1724, was a British politician, bibliophile, collector and patron of the arts.

Background

Harley was the only son of Rober ...

, who would be a powerful patron and friend (Gibbs would later remodel the Earl's house Wimpole Hall

Wimpole Estate is a large estate containing Wimpole Hall, a country house located within the civil parish of Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, England, about southwest of Cambridge. The house, begun in 1640, and its of parkland and farmland are owned ...

) and James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, (6 January 16739 August 1744) was an English landowner and politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1698 until 1714, when he succeeded to the peerage as Baron Chandos, and vacated ...

(for whom he would be one of the architects to work at Cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder dur ...

from 1715 to 1719). Gibbs was one of the sixty founder members of Godfrey Kneller

Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1st Baronet (born Gottfried Kniller; 8 August 1646 – 19 October 1723), was the leading portrait painter in England during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and was court painter to English and British monarchs from ...

's Academy of Painting, founded in 1711. In August 1713 Gibbs discovered that William Dickinson was resigning as architect from the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches

The Commission for Building Fifty New Churches (in London and the surroundings) was an organisation set up by Act of Parliament in England in 1711, the New Churches in London and Westminster Act 1710, with the purpose of building fifty new church ...

; the commissioners included Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restora ...

and Thomas Archer

Thomas Archer (1668–1743) was an English Baroque architect, whose work is somewhat overshadowed by that of his

contemporaries Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor. His buildings are important as the only ones by an English Baroque archit ...

. With the backing of, amongst others, the Earl of Mar and Sir Christopher Wren, Gibbs was appointed architect to the commission on 18 November 1713,Friedman, p.10 where he would have worked with Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

, his fellow architect to the commission. But a combination of events would ensure Gibbs was deprived of his place as architect to the commission by December 1715: Queen Anne had died and a Whig government had replaced the Tories; and the failure of the 1715 Jacobite rising

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( gd, Bliadhna Sheumais ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland for the exiled Stuarts.

At Braemar, Aberdeenshire, lo ...

that was supported by the Earl of Mar were all factors. Still he was able to complete one church, St Mary-le-Strand, that he described as "the first publick (sic) building I was employed in after my arrival from Italy; which being situated in a very publick place, the Commissioners... spar'd no cost to beautify". On 18 December 1716 Gibbs joined the "Vandykes clubb" ( sic), also called the Club of St Luke for "Virtuosi in London". Fellow architects who were members included William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, bu ...

and William Talman; other notable members with whom Gibbs would later work included the garden designer Charles Bridgeman

Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738) was an English garden designer who helped pioneer the naturalistic landscape style. Although he was a key figure in the transition of English garden design from the Anglo-Dutch formality of patterned parterres an ...

and the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemish sculptor, who spent most of his career in England where h ...

, who sculpted many of the memorials Gibbs designed. In March 1721 Charles Bridgeman, James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill (25 July 1675 or 1676 – 4 May 1734) was an English painter of historical subjects working in the Italian baroque tradition. He was responsible for some large-scale schemes of murals, including the "Painted Hall" at the Ro ...

, John Wootton and Gibbs were all travelling together from London to Wimpole Hall where they were all working for Edward Harley, the Earl of Oxford; Thornhill recalled that they drank Harley's "healths over and over, as well in our civil as bacchanalian hours" and talked "of building, pictures and may be towards the close of politics or religion".

In 1720 Gibbs was invited along with other architects to enter a competition to design a new church to replace the dilapidated church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. He won, and on 24 November 1720 he was appointed architect of the new church, which was to be his most famous building. Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whig politician.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twi ...

described Gibbs as being around 1720 as "the architect most in vogue". In 1720 Gibbs was approached by the Provost of King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

to complete the college. The scheme consisted of three buildings, all high, forming a courtyard to the south of the Chapel. In the end only the western block, the long Fellows' Building, was constructed from 1721 to 1724; the eastern Fellows' Building would have been identical, and the southern building would have had a great octastyle Corinthian portico, and been long, containing the great dining hall, Provost's Lodge and offices. On 11 December 1721 Edward Lany, one of the Syndics of University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, thanked Edward Harley Earl of Oxford for sending "Mr Gibbs's design for our building. I design to offer it to the Syndics as soon as they meet...I have not skill enough myself to judge of it".Friedman, p.225 This referred to a design for a new central building for the University to house the library, Senate House, the Consistory and Register Offices. Gibbs produced a second larger design in 1722, consisting of a courtyard building with two projecting wings to the east, . Work started on the building in November 1722, but in the end only the Senate House, , the northern of the two east wings, was built. It was finished in 1730.

By 1723 Gibbs was rich enough to open an account at Drummonds Bank

Messrs. Drummond is a formerly independent private bank that is now owned by NatWest Group. The Royal Bank of Scotland incorporating Messrs. Drummond, Bankers is based at 49 Charing Cross in central London. Drummonds is authorised as a brand of ...

, with his first year's balance being £1055 11 shillings 4 pence. 1723 also saw Gibbs being made a governor of St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

;Friedman, p.214 other governors included fellow architects Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork, (25 April 1694 – 4 December 1753) was a British architect and noble often called the "Apollo of the Arts" and the "Architect Earl". The son of the 2nd Earl of Burlington and 3rd Ea ...

and George Dance the Elder

George Dance the Elder (1695 – 8 February 1768) was a British architect. He was the City of London surveyor and architect from 1735 until his death.

Life

Originally a mason, George Dance was appointed Clerk of the city works to the City of ...

. On 1 August 1728 it was decided to rebuild the Hospital. Gibbs offered his service for free, and designed a quadrangle of with four near-identical plain blocks. In March 1726 Gibbs was made a member of the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

.Friedman, p.16 and in 1727 he was awarded with the only government post he ever held, Architect of the Ordnance, which he held for life. He was given it thanks to the Duke of Argyll who was Master of the Ordnance and in 1729 he was elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. One of the most serious disappointments of Gibbs's career was his failure to win the commission for the Mansion House, London. There were two competitions for the building, both of which he entered – the first in 1728 and a second in 1735; in the end George Dance the Elder won the commission. In 1735, Gavin Hamilton painted ''A Conversation of Virtuosis... at the Kings Arms'', a group portrait that included Michael Dahl

Michael Dahl (1659–1743) was a Swedish portrait painter who lived and worked in England most of his career and died there. He was one of the most internationally known Swedish painters of his time. He painted portraits of many aristocrats and s ...

, George Vertue

George Vertue (1684 – 24 July 1756) was an English engraver and antiquary, whose notebooks on British art of the first half of the 18th century are a valuable source for the period.

Life

Vertue was born in 1684 in St Martin-in-the-Fields, ...

, John Wootton

John Wootton (c.1686– 13 November 1764)Deuchar, S. (2003). "Wootton, John". Grove Art Online. was an English painter of sporting subjects, battle scenes and landscapes, and illustrator.

Life

Born in Snitterfield, Warwickshire (near Stratfo ...

, Gibbs and Rysbrack, along with other artists who were instrumental in bringing the Rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

style to English design and interiors. After the death in 1736 of Nicholas Hawksmoor, who was architect for the Radcliffe Camera, Gibbs was appointed on 4 March 1737 to replace him. The Radcliffe Camera was finished by 19 May 1749. Gibbs was awarded by Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

an honorary degree of Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

in 1749 recognition of the completion of the Radcliffe Camera.

Collections

A list of the nearly 700 books in his library is preserved in theBodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the sec ...

. While architecture and related crafts made up the bulk of his books, other subjects covered included antiquities, coins, and heraldry; histories of England, Scotland and Rome and other nations; literature including works by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Du ...

, Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

and Matthew Prior; travel books including Egypt, the South Seas, Russia, Hungary, Lapland, Virginia, Ceylon and Abyssinia; missionary travels including China, Formosa, Guinea, Borneo and the East Indies; books on religion including both Anglican and Roman Catholic works; and even cookery books. The most significant of the architectural works were Vincenzo Scamozzi

Vincenzo Scamozzi (2 September 1548 – 7 August 1616) was an Italian architect and a writer on architecture, active mainly in Vicenza and Republic of Venice area in the second half of the 16th century. He was perhaps the most important figure t ...

's ''L'Idea dell'Architettura Universale'', Sebastiano Serlio

Sebastiano Serlio (6 September 1475 – c. 1554) was an Italian Mannerist architect, who was part of the Italian team building the Palace of Fontainebleau. Serlio helped canonize the classical orders of architecture in his influential trea ...

's ''Sette Libri d'Architettura'', Domenico Fontana

Domenico Fontana (154328 June 1607) was an Italian architect of the late Renaissance, born in today's Ticino. He worked primarily in Italy, at Rome and Naples.

Biography

He was born at Melide, a village on the Lake Lugano, at that time join ...

's ''Della transportatione dell'obelisco Vaticano e delle fabriche di Sisto V'', Colen Campbell

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

's ''Vitruvius Britannicus'', Giacomo Leoni's ''The Architecture of A. Palladio, in Four Books'', William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, bu ...

's ''The Designs of Inigo Jones'' and Robert Wood's ''The ruins of Palmyra''. Gibbs is also known to have owned at least 117 paintings, including works by Canaletto

Giovanni Antonio Canal (18 October 1697 – 19 April 1768), commonly known as Canaletto (), was an Italian painter from the Republic of Venice, considered an important member of the 18th-century Venetian school.

Painter of city views or ...

, Giovanni Paolo Panini

Giovanni Paolo Panini or Pannini (17 June 1691 – 21 October 1765) was an Italian painter and architect who worked in Rome and is primarily known as one of the ''vedutisti'' ("view painters"). As a painter, Panini is best known for his vistas of ...

, Sebastiano Ricci

Sebastiano Ricci (1 August 165915 May 1734) was an Italian painter of the late Baroque school of Venice. About the same age as Piazzetta, and an elder contemporary of Tiepolo, he represents a late version of the vigorous and luminous Cortonesq ...

, Antoine Watteau and Willem van de Velde the Younger

Willem van de Velde the Younger (18 December 1633 (baptised)6 April 1707) was a Dutch marine painter, the son of Willem van de Velde the Elder, who also specialised in maritime art. His brother, Adriaen van de Velde, was a landscape painter.

...

.Little, p.23 Sculptures owned by Gibbs included a bust of Flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring ( indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

...

by François Girardon

François Girardon (10 March 1628 – 1 September 1715) was a French sculptor of the Louis XIV style or French Baroque, best known for his statues and busts of Louis XIV and for his statuary in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles.

Biograph ...

, a bust of Matthew Prior by Antoine Coysevox

Charles Antoine Coysevox ( or ; 29 September 164010 October 1720), was a French sculptor in the Baroque and Louis XIV style, best known for his sculpture decorating the gardens and Palace of Versailles and his portrait busts.

Biography

Coysevo ...

and busts of Alexander Pope and Gibbs by Rysbrack.

Death and will

By 1743 Gibbs, who was fond of wine and food, was described as "corpulent". In June 1749 Gibbs set out for the

By 1743 Gibbs, who was fond of wine and food, was described as "corpulent". In June 1749 Gibbs set out for the spa town

A spa town is a resort town based on a mineral spa (a developed mineral spring). Patrons visit spas to "take the waters" for their purported health benefits.

Thomas Guidott set up a medical practice in the English town of Bath, Somerset, B ...

of Aix-la-Chapelle

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

for treatment: he long suffered from kidney stone

Kidney stone disease, also known as nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis, is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material (kidney stone) develops in the urinary tract. Kidney stones typically form in the kidney and leave the body in the urine s ...

s and had lost weight and was in pain. He remained until September when he returned to London. Gibbs never married. He died in his London house on the corner of Wimpole Street

Wimpole Street is a street in Marylebone, central London. Located in the City of Westminster, it is associated with private medical practice and medical associations. No. 1 Wimpole Street is an example of Edwardian baroque architecture, comple ...

and Henrietta Street on 5 August 1754 and was buried in St Marylebone Parish Church

St Marylebone Parish Church is an Anglican church on the Marylebone Road in London. It was built to the designs of Thomas Hardwick in 1813–17. The present site is the third used by the parish for its church. The first was further south, near Ox ...

, and a modest wall tablet was erected with this inscription:

Underneath lye the Remains of JAMESIn his will made on 9 May 1754, Gibbs left £1000, his Plate, and three houses in

GIBBS Esqr. whose Skill in Architecture

appears by his Printed Works as well

as the Buildings directed by him,

Among other Legacys & Charitys

He left One Hundred Pounds towards

Enlarging this Church

He died Augt. 5th. 1754.

Aged 71.

Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

to Lord Erskine in gratitude for favours from his father the late Earl of Mar. Further bequests included £1,400 and two houses in Marylebone and Argyll Ground Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

to John Sherwine of Soho plus £100 to be given to a charity of Sherwine's daughters choice, to Robert Pringle of Clifton a Cavendish Square

Cavendish Square is a public garden square in Marylebone in the West End of London. It has a double-helix underground commercial car park. Its northern road forms ends of four streets: of Wigmore Street that runs to Portman Square in the much ...

house and £400 and to Cosmo Alexander

Cosmo Alexander (1724 – 25 August 1772) was a Scottish portrait painter. A supporter of James Edward Stuart's claim to the English and Scottish thrones, Alexander spent much of his life overseas following the defeat of the Jacobite cause in ...

(1724–1772) a Scottish painter "my house I live in withall icits furniture as it stands with pictures bustoes icetc". Further bequests of £100 each went to William Thomas, Dr. William King, St Bartholomew's Hospital and the Foundling Hospital

The Foundling Hospital in London, England, was founded in 1739 by the philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram. It was a children's home established for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children." The word " hospita ...

. The Trustees of Radcliffe Camera were given "all my printed books, Books of Architecture books of prints and drawings books of maps and a pair of globes with leather covers to be placed ... in the library... of which I was architect ... next to my Bustoe".

Architecture

Early works

Mar attached Gibbs' name among the list of architects to be responsible for the new churches to be built under the Act for Fifty New Churches, and in 1713 he was appointed one of the Commission's two surveyors, the contemporary term for an architect, alongsideNicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

. He held this post for two years, until he was forced out by the Whigs, because of his Tory sympathies, and replaced by John James. During his tenure he completed his first important commission, the church of St Mary-le-Strand (1714–17), in the City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a city and borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of central Greater London, including most of the West En ...

. A previous design had been prepared by the English Baroque

English Baroque is a term used to refer to modes of English architecture that paralleled Baroque architecture in continental Europe between the Great Fire of London (1666) and roughly 1720, when the flamboyant and dramatic qualities of Baroque ...

architect Thomas Archer

Thomas Archer (1668–1743) was an English Baroque architect, whose work is somewhat overshadowed by that of his

contemporaries Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor. His buildings are important as the only ones by an English Baroque archit ...

, which Gibbs developed in an Italian Mannerist

Mannerism, which may also be known as Late Renaissance, is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Ita ...

style, influenced by the Palazzo Branconio dall'Aquila in Rome, attributed to Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

, as well as incorporating elements from Wren. Such strong Italian influence was not popular with the Whigs, who were now taking political control following the accession of King George I in 1714, leading to Gibbs' dismissal, and causing him to modify the foreign influences in his work.Summerson, p.324 Colen Campbell's ''Vitruvius Britannicus

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

'' (1715), which promoted the Palladian style, also contains unfavourable comments regarding Carlo Fontana and St Mary-le-Strand. Campbell went on to replace Gibbs as the architect of Burlington House

Burlington House is a building on Piccadilly in Mayfair, London. It was originally a private Neo-Palladian mansion owned by the Earls of Burlington and was expanded in the mid-19th century after being purchased by the British government. To ...

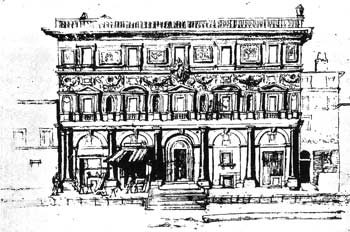

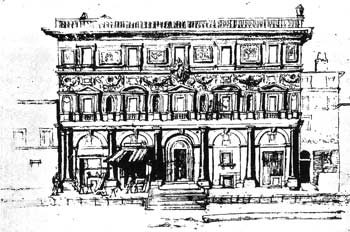

around 1717, where the latter had designed the offices and colonnades for the young Lord Burlington.

Other early designs include the house of

Other early designs include the house of Cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder dur ...

, Middlesex (1716–20), for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, (6 January 16739 August 1744) was an English landowner and politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1698 until 1714, when he succeeded to the peerage as Baron Chandos, and vacated ...

, and the tower of Wren's St Clement Danes

St Clement Danes is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Although the first church on the site was reputedly founded in the 9th century by the Danes, the current ...

(1719). At Twickenham

Twickenham is a suburban district in London, England. It is situated on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames since 1965, and the boro ...

he designed the pavilion at Orleans House, called the Octagon Room, for a Scottish patron, James Johnston (1655–1737) former Secretary of State for Scotland, about 1720. It is the only part of the house and grounds that has survived.

Country houses

Gibbs' mature style emerges in the early 1720s, with the house ofDitchley

Ditchley Park is a country house near Charlbury in Oxfordshire, England. The estate was once the site of a Roman villa. Later it became a royal hunting ground, and then the property of Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley. The 2nd Earl of Lichfield built ...

, Oxfordshire (1720–22), for George Lee, 2nd Earl of Lichfield

George Henry Lee I, 2nd Earl of Lichfield (1690–1743) was a younger son of Edward Henry Lee, 1st Earl of Lichfield and his wife Charlotte Fitzroy, an illegitimate daughter of Charles II by his mistress, the celebrated courtesan Barbara Vi ...

. It typifies his conservative domestic manner, which changed little throughout the rest of his career.Summerson, p.326 His other houses include Sudbrooke Lodge, Petersham (1728), for the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll ( gd, Diùc Earraghàidheil) is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerfu ...

, works at Wimpole Hall

Wimpole Estate is a large estate containing Wimpole Hall, a country house located within the civil parish of Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, England, about southwest of Cambridge. The house, begun in 1640, and its of parkland and farmland are owned ...

, Cambridgeshire, for the 2nd Earl of Oxford, Patshull Hall, Staffordshire (1730) for Sir John Astley, and modifications to Colen Campbell

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

's designs at Houghton Hall

Houghton Hall ( ) is a country house in the parish of Houghton in Norfolk, England. It is the residence of David Cholmondeley, 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley.

It was commissioned by the ''de facto'' first British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Wa ...

in Norfolk. Gibbs also completed the Gothic Temple (1741–48), a triangular folly

In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings.

Eighteenth-cent ...

at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, and now one of the properties leased and maintained by The Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then makes them available for holiday rental. The Trust's headqua ...

. Other garden buildings at Stowe include the pair of "Boycott Pavilions", which were altered by Giovanni Battista Borra in 1754 to replace the pyramidal stone roofs with more conventional domes.

Churches

Gibbs designed one church for theCommission for Building Fifty New Churches

The Commission for Building Fifty New Churches (in London and the surroundings) was an organisation set up by Act of Parliament in England in 1711, the New Churches in London and Westminster Act 1710, with the purpose of building fifty new church ...

, St Mary le Strand

St Mary le Strand is a Church of England church at the eastern end of the Strand in the City of Westminster, London. It lies within the Deanery of Westminster (St Margaret) within the Diocese of London. The church stands on what was until rec ...

. Construction began in 1714 and it was complete by 1717. Between 1721 and 1726 Gibbs designed his most important and influential work, the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

, located in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, London. Gibbs' initial radical design for the commission was for a circular church, derived from a design by Andrea Pozzo

Andrea Pozzo (; Latinized version: ''Andreas Puteus''; 30 November 1642 – 31 August 1709) was an Italian Jesuit brother, Baroque painter, architect, decorator, stage designer, and art theoretician.

Pozzo was best known for his grandiose fresc ...

; its illustration in Gibbs' book was to influence several adaptations by Neoclassical architects

Neoclassical architecture is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy and France. It became one of the most prominent architectural styles in the Western world. The prevailing sty ...

.Summerson, p.327 This was rejected by the commission, and Gibbs developed the present rectangular design. The layout and detailing of the building owes much to Wren, in particular the church of St James', Piccadilly. However, Gibbs' innovation at St Martin's was to place the steeple centrally, behind the pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

.Summerson, p.330 By contrast, Wren's steeples were usually adjacent to the church, rather than within the walls. This apparent incongruity was criticised at the time, but St Martin-in-the-Fields nevertheless became a model for church buildings, particularly for Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

worship, across Britain and around the world.

At the same time, Gibbs designed a chapel of ease

A chapel of ease (or chapel-of-ease) is a church building other than the parish church, built within the bounds of a parish for the attendance of those who cannot reach the parish church conveniently.

Often a chapel of ease is deliberately bu ...

for the 1st Earl of Oxford, now known as St Peter, Vere Street (1721–24). In 1725 he designed All Saints', Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

, now Derby Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of All Saints Derby, better known as Derby Cathedral, is a cathedral church in the city of Derby, England. In 1927, it was promoted from parish church status, to a cathedral, creating a seat for the Bishop of Derby, ...

, on similar lines to St Martin's, although at Derby the original gothic steeple was retained. Gibbs, the first British architect to do so, created numerous designs for funeral monuments, often collaborating with the sculptor Michael Rysbrack. In 1733 Gibbs was commissioned by Lord Foley to adapt the chapel from Cannons House (Gibbs was one of the architects involved in designing Cannons), as the parish church at Great Witley.

St Bartholomew's Hospital

In 1723 Gibbs was appointed a governor of

In 1723 Gibbs was appointed a governor of St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

, which led to him being commissioned to redesign the hospital. In 1728 he produced a design with four near identical blocks around a square ; he gave his services for free. The first block to be built, the north, administration block was constructed from 9 June 1730, using Bath Stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of ...

(this would be used for all the blocks). It was finished in 1732 and contains the Great Hall and the main staircase, the walls of which are covered by murals painted by William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like ...

, depicting Christ healing the sick at the Pool of Bethesda

The Pool of Bethesda is a pool in Jerusalem known from the New Testament account of Jesus miraculously healing a paralysed man, from the fifth chapter of the Gospel of John, where it is described as being near the Sheep Gate, surrounded by f ...

and the parable of the good Samaritan

The parable of the Good Samaritan is told by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. It is about a traveler (implicitly understood to be Jewish) who is stripped of clothing, beaten, and left half dead alongside the road. First, a Jewish priest and then ...

. The other blocks contained wards. The south block was built from 1735 to 1740 (demolished 1937). the west block was built from 1743 to 1753; it was delayed due to the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

. The east block was built 1758–68 to Gibbs' design.

Universities

Gibbs worked at both

Gibbs worked at both Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

Universities. He shares the credit, with James Burrough, for designing the Senate House at Cambridge. The Fellows' Building at King's College (1724–30) is his work entirely. A simple composition, similar in style to his houses, the building is enlivened by a central feature incorporating an arch, within a doric portal, and a Diocletian window, all under a pediment. This mannerist composition of features from Wren and Palladio is an example of Gibbs' more adventurous Italian style.

More adventurous still was Gibbs' last major work, the Radcliffe Camera, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

(1739–49). A circular library building was first planned by Hawksmoor around 1715, but nothing was done at the time. Sometime before 1736, new designs were submitted by Hawksmoor and Gibbs, with the latter's rectangular design being preferred. However, this plan was abandoned in favour of a circular plan by Gibbs, which drew on Hawksmoor's 1715 scheme, although it was very different in detail.Summerson, p.333 Gibbs' design saw him returning to his Italian mannerist sources, and in particular shows the influence of Santa Maria della Salute

Santa Maria della Salute ( en, Saint Mary of Health), commonly known simply as the Salute, is a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica located at Punta della Dogana in the Dorsoduro sestiere of the city of Venice, Italy.

It stands on the na ...

, Venice (1681), by Baldassarre Longhena

Baldassare Longhena (1598 – 18 February 1682) was an Italian architect, who worked mainly in Venice, where he was one of the greatest exponents of Baroque architecture of the period.

Biography

Born in Venice, Longhena studied under the architect ...

. The building incorporates unexpected vertical alignments: for instance, the ribs of the dome do not line up with the columns of the drum, but lie in between, creating a rhythmically complex composition.

Published works

Gibbs published the first edition of ''A Book of Architecture, containing designs of buildings and ornaments'' in 1728, dedicated to one of his patronsJohn Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll

Field Marshal John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, 1st Duke of Greenwich, (10 October 1680 – 4 October 1743), styled Lord Lorne from 1680 to 1703, was a Scottish nobleman and senior commander in the British Army. He served on the contine ...

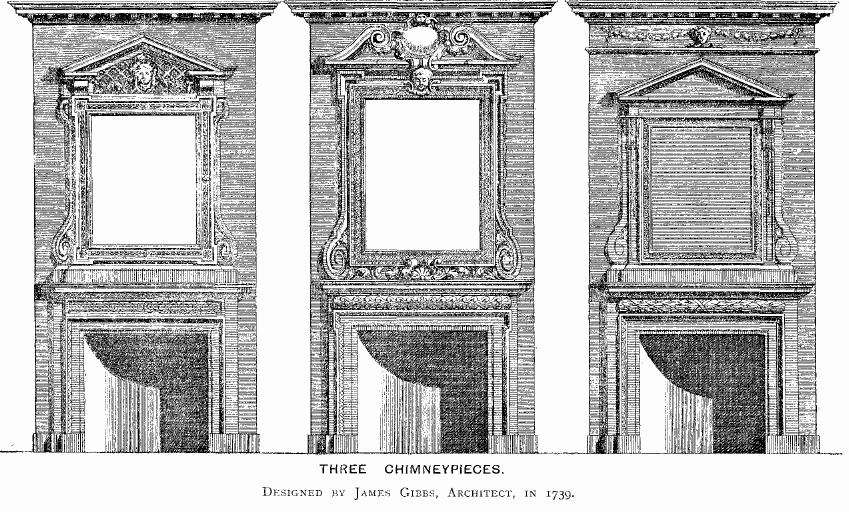

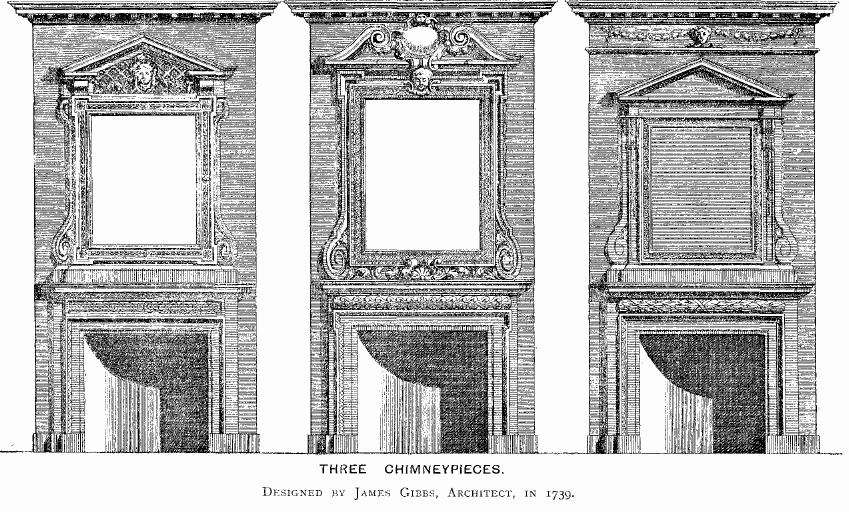

. It was a folio of his building designs both executed and not, as well as numerous designs for ornaments and including 150 engraved plates covering 380 different designs. He was the first British architect to publish a book devoted to his own designs. The major works illustrated include St Martin-in-the-Fields (including the unexecuted version with a circular nave), St Mary le Strand, the complete schemes for King's College Cambridge and the Public Building (including the Senate House) at Cambridge University, numerous designs for medium-sized country houses, garden building and follies, obelisks and memorial columns, church memorials and monuments, as well as wrought-iron work, fireplaces, window and door surrounds, Cartouche (design) and urns. The first page of the introduction included: '...such a Work as this would be of use to such Gentleman as might be concerned in Building, especially in the remote parts of the Country, where little or no assistance for designs can be procured'. It was intended to be a pattern book for both architects and clients, and became, according to John Summerson, "probably the most widely-used architecture book of the century, not only throughout Britain, but in the American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

". For example, Plate 58 was an inspiration for the river façade of Mount Airy, Richmond County, Virginia, and perhaps also for the floorplan of Drayton Hall

Drayton Hall is an 18th-century plantation located on the Ashley River about 15 miles (24 km) northwest of Charleston, South Carolina, and directly across the Ashley River from North Charleston, west of the Ashley in the Lowcountry. An exa ...

in Charleston County, South Carolina.

Other published works by Gibbs include ''The Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture'' (1732), which explained how to draw the Classical order

An order in architecture is a certain assemblage of parts subject to uniform established proportions, regulated by the office that each part has to perform.

Coming down to the present from Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman civilization, the arc ...

s and related details and was used well into the 19th century, and ''Bibliotheca Radcliviana'' subtitled ''A Short Description of the Radcliffe Library Oxford'' (1747) to celebrate the Radcliffe Camera, including a list of all the craftsmen employed in the building's construction as well as twenty-one plates. In 1752 he published a two-volume translation of the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

book ''De Rebus Emanuelis'' by a 16th-century Portuguese Bishop Jerome Osorio da Fonseca; his English title was ''The History of the Portuguese during the Reign of Emanuel''. It is a history book with accounts of warfare, voyages of discovery from Africa to China (including descriptions of the religious beliefs of these countries) and also the initial colonisation of Brazil.

List of architectural works

The following list includes Gibbs' most significant works.Secular Works

* Senate House, Cambridge University 1721–30 *King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

, Fellows Building 1724–42, sole completed part of Gibbs' proposed rebuilding of the college

*Oxford Market House, Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

, London, 1726–37, demolished 1880–81

*St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

, Smithfiled, London 1728–68, rebuilding of medieval and later hospital,Gibbs south block demolished 1937

*Marylebone Court House, Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

, London, 1729–33, demolished 1803–04

* Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University 1736–49

*Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a ford on the River Lea, n ...

Town Hall, 1737 (unexecuted)

*Codrington Library

All Souls College Library, known until 2020 as the Codrington Library, is an academic library in the city of Oxford, England. It is the library of All Souls College, a graduate constituent college of the University of Oxford.

The library in its ...

, All Souls College, Oxford

All Souls College (official name: College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full members of ...

, completion of interior following the death of architect Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

, 1740–50

*St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pr ...

, new screen in the Hall, 1743

Senate House, Cambridge

The Senate House is a 1720s building of the University of Cambridge in England, used formerly for meetings of its senate and now mainly for graduation ceremonies.

Location and construction

The building, which is situated in the centre of the ...

File:Senate House.jpg, Detail of pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

, Senate House, Cambridge

File:King's College, Cambridge, in the snow 3.jpg, East front, Fellows' Building, King's College Cambridge

File:Great Hall, St Bartholomew's Hospital, London-15105228146.jpg, Great Hall, St Bartholomew's Hospital

File:William Hogarth murals, St Bartholomew's Hospital, London-15125229461.jpg, Staircase with Hogarth mural paintings, St Bartholomew's Hospital

File:East Block Facade facing courtyard.JPG, Centre of east block, St Bartholomew's Hospital

Ecclesiastical Works

*St Mary le Strand

St Mary le Strand is a Church of England church at the eastern end of the Strand in the City of Westminster, London. It lies within the Deanery of Westminster (St Margaret) within the Diocese of London. The church stands on what was until rec ...

, London, 1713–24

*Steeple, added to Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

's church of St Clement Danes

St Clement Danes is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Although the first church on the site was reputedly founded in the 9th century by the Danes, the current ...

, London, 1719–21

*St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

, London, 1720–27

*Marybone Chapel

St Peter, Vere Street, known until 1832 as the Oxford Chapel after its founder Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, is a former Anglican church off Oxford Street, London. It has sometimes been referred to as the Marybone Chap ...

(now St Peter's Vere Street, used as offices), London, 1721–24

*St Giles Church, Shipbourne

Shipbourne ( ) is a village and civil parish situated between the towns of Sevenoaks and Tonbridge, in the borough of Tonbridge and Malling in the English county of Kent. In 2020 it was named as the most expensive village in Kent.

It is located i ...

, Kent, 1722–23, rebuilt 1880–81

*St Mary's Church, Mapleton, Derbyshire

Mapleton, sometimes spelt Mappleton, is a village and a civil parish in the Derbyshire Dales District, in the English county of Derbyshire. It is near the River Dove, Central England, River Dove and the town of Ashbourne, Derbyshire, Ashbourne. M ...

, c.1723

*Derby Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of All Saints Derby, better known as Derby Cathedral, is a cathedral church in the city of Derby, England. In 1927, it was promoted from parish church status, to a cathedral, creating a seat for the Bishop of Derby, ...

, formerly All Saints, Derby, rebuilding of existing church except for the tower, 1723–26

*Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln Minster, or the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln and sometimes St Mary's Cathedral, in Lincoln, England, is a Grade I listed cathedral and is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Lincoln. Construc ...

, strengthening of western towers, 1725–26

*St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley, Worcestershire, using decoration and fittings from the chapel at Cannons, 1733–47

*Chandos Mausoleum

The Chandos Mausoleum is an early 18th-century English Baroque building by James Gibbs in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. The mausoleum is attached to the north side of the church of St Lawrence Whitchurch in the London Borough of ...

, St Lawrence, Whitchurch, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

, for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, (6 January 16739 August 1744) was an English landowner and politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1698 until 1714, when he succeeded to the peerage as Baron Chandos, and vacated ...

, 1735–36

*Kirk of St Nicholas, Aberdeen

The Kirk of St Nicholas is a historic church located in the city centre of Aberdeen, Scotland. Up until the dissolution of the congregation on 31 December 2020, it was known as the ''"Kirk of St Nicholas Uniting"''. It is also known as ''"The Mit ...

, new nave 1741–55

*Turner Mausoleum, Kirkleatham Church, North Yorkshire, 1740

* Sir William Turner's Hospital Chapel, Kirkleatham 1741

* St Mary's Church, Patshull Hall, Staffordshire, 1742

Church memorials

*Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, to John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

, poet, 1720–21

*Westminster Abbey, to John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby

John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby, (7 April 164824 February 1721) was an English poet and Tory politician of the late Stuart period who served as Lord Privy Seal and Lord President of the Council. He was also known by his ori ...

, 1721–22

*Westminster Abbey, to John Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle

John Holles, Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, KG, PC (9 January 1662 – 15 July 1711) was an English peer.

Early life

Holles was born in Edwinstowe, Nottinghamshire, the son of the 3rd Earl of Clare and his wife Grace Pierrepont. Grace was a d ...

, 1721–23, sculpted by Francis Bird.

*Westminster Abbey, to Matthew Prior, 1721–23

*Westminster Abbey, to Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

, playwright, c.1723

*Westminster Abbey, to John Smith, 1723

*St Giles Church, Shipbourne, to Christopher Vane, 1st Baron Barnard

Christopher Vane, 1st Baron Barnard (21 May 1653 – 28 October 1723) was an English peer. He served in Parliament for Durham after his brother, Thomas, died 4 days after being elected the MP for Durham. Then, again from January 1689 - November ...

, 1723, re-erected when the church was rebuilt

*Westminster Abbey, to William Johnstone, 1st Marquess of Annandale, James Johnstone, 2nd Marquess of Annandale

James Johnstone, 3rd Earl of Annandale and Hartfell and 2nd Marquess of Annandale (c.1687–1730) was a Scottish politician who sat in the British House of Commons briefly in 1708 before being disqualified as eldest son of a Scottish peer.

John ...

and his wife Sophia Fairholm, 1723

*Westminster Abbey, to James Craggs the Younger, 1724–27

*St Mary's Amersham

Amersham ( ) is a market town and civil parish within the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire, England, in the Chiltern Hills, northwest of central London, from Aylesbury and from High Wycombe. Amersham is part of the London commuter be ...

, to Montague & Jane Drake, 1725

*SS. Peter & Paul, Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles from Birmingham City Centre.

History

Aston wa ...

, to Sir John & Lady Bridgeman, 1726

*SS. Peter & Paul, Mitcham

Mitcham is an area within the London Borough of Merton in South London, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross. Originally a village in the county of Surrey, today it is mainly a residential suburb, and includes Mitcham Common. It h ...

, to Sir Ambrose & Lady Crowley, c.1727

*St Mary's Bolsover

Bolsover is a market town and the administrative centre of the Bolsover District, Derbyshire, England. It is from London, from Sheffield, from Nottingham and from Derby. It is the main town in the Bolsover district.

The civil parish for th ...

, to Henry Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, 1727–28, sculpted by Francis Bird

Francis Bird (1667–1731) was one of the leading English sculptors of his time. He is mainly remembered for sculptures in Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral. He carved a tomb for the dramatist William Congreve in Westminster Abbey and ...

.

*Westminster Abbey, Catherina Boevey, 1727–28, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack.

*St Margaret's, Westminster

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster ...

, to Robert Stuart, 1728

*All Saints' Church, Bristol

All Saints is a closed Anglican church in Corn Street, Bristol. For many years it was used as a Diocesan Education Centre but this closed in 2015. The building has been designated as a grade II* listed building.

History

The west end of the nav ...

, to Edward Colston

Edward Colston (2 November 1636 – 11 October 1721) was an English merchant, slave trader, philanthropist, and Tory Member of Parliament.

Colston followed his father in the family business becoming a sea merchant, initially trading in wine, ...

, slave-trader and philanthropist, 1728–29, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemish sculptor, who spent most of his career in England where h ...

.

*All Saints, Maiden Bradley

Maiden Bradley is a village in south-west Wiltshire, England, about south-west of Warminster and bordering the county of Somerset. The B3092 road between Frome and Mere forms the village street. Bradley House, the seat of the Duke of Som ...

, to Sir Edward Seymour, 4th Baronet, 1728–30, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack.

*Westminster Abbey, to Dr John Friend, 1730–31

*Turner Mausoleum, Kirkleatham Church, Monument to Marwood William Turner, 1739–41

*All Saints Soulbury

Soulbury is a village and also a civil parish within the unitary authority area of Buckinghamshire, England. It is located in the Aylesbury Vale, about seven miles south of Central Milton Keynes, and three miles north of Wing. The village na ...

, to Robert Lovett, c.1740

*St Marylebone Parish Church

St Marylebone Parish Church is an Anglican church on the Marylebone Road in London. It was built to the designs of Thomas Hardwick in 1813–17. The present site is the third used by the parish for its church. The first was further south, near Ox ...

, own memorial (Gibbs was buried in the previous church, 1754), transferred to the present church

London houses

*Houses in the Privy Gardens,Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

, London, 1710–11, demolished 1807

*Burlington House

Burlington House is a building on Piccadilly in Mayfair, London. It was originally a private Neo-Palladian mansion owned by the Earls of Burlington and was expanded in the mid-19th century after being purchased by the British government. To ...

, Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Cour ...

, wings and twin colonnades in forecourt, 1715–16, demolished

*Thanet House, Great Russell Street, Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

1719, demolished

*9–11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

1723–27, demolished 1956; drawing room from No.11 preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

*52 Grosvenor Street, Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world ...

alterations 1727

*Savile House, 6 Leicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicest ...

, 1733, demolished

*25 Leicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicest ...

, 1733–34 demolished

*49 Great Ormond Street, new library, 1734, demolished

*16 Arlington Street, Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world ...

1734–40