James Farmer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the

In 1961, Farmer, who was working for the

In 1961, Farmer, who was working for the

In 1963, Louisiana state troopers hunted him door to door for trying to organize protests. A funeral home director had Farmer play dead in the back of a hearse that carried him along back roads and out of town. He was arrested that August for disturbing the peace.

As the Director of CORE, Farmer was considered one of the " Big Six" of the

In 1963, Louisiana state troopers hunted him door to door for trying to organize protests. A funeral home director had Farmer play dead in the back of a hearse that carried him along back roads and out of town. He was arrested that August for disturbing the peace.

As the Director of CORE, Farmer was considered one of the " Big Six" of the

Fund for an Open Society

Its vision is a nation in which people live in stably integrated communities, where political and civic power is shared by people of different races and ethnicities. He led this organization until 1999. Farmer was named an honorary vice chairman of the

Who is James Farmer retrieved April 5, 2011

Several issues of ''Fellowship'' magazine of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1992 (Spring, Summer and Winter issues) contained discussions by Farmer and

"Who is James Farmer?"

University of Mary Washington

University of Texas Libraries. Accessed 2014.

James Farmer Lectures at University of Mary Washington

University of Mary Washington James Farmer Oral History Project

Oral History Interviews with James Farmer, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

FBI file on James Farmer

;Videos

Dr. James Farmer Jr. Civil Rights Documentary “The Good Fight” Fascinates And Educates, Movie Review from ShortFilmTexas.com

''You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!'' New Hampshire Public Television/American Public Television documentary of the Journey of Reconciliation

''Eyes on the Prize'' Blackside, Inc./PBS documentary of the Civil Rights Movement (Episode 3 is the Freedom Rides)

''Freedom Riders'' 50th anniversary documentary, PBS's American Experience

James Farmer

on the WGBH serie

The Ten O'Clock News

*

Civil Rights Greensboro: James Farmer

Biography

at Encyclopedia Virginia *

Harambee City

Archival site incorporating big documents, maps, audio/visual materials related to CORE's work in black power and black economic development.

Image of the United Civil Rights Committee at a march against de facto school segregation in Los Angeles, California, 1963.

''

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

"who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." He was the initiator and organizer of the first Freedom Ride in 1961, which eventually led to the desegregation of interstate transportation in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

In 1942, Farmer co-founded the Committee of Racial Equality in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

along with George Houser

George Mills Houser (June 2, 1916 – August 19, 2015) was an American Methodist minister, civil rights activist, and activist for the independence of African nations. He served on the staff of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (1940s – 1950s). ...

, James R. Robinson, Samuel E. Riley, Bernice Fisher, Homer Jack, and Joe Guinn. It was later called the Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE), and was dedicated to ending racial segregation in the United States

In the United States, racial segregation is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation on racial grounds. The term is mainly used in reference to the legally ...

through nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. Farmer served as the national chairman from 1942 to 1944.

By the 1960s, Farmer was known as "one of the Big Four civil rights leaders in the 1960s, together with King, NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

chief Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the ...

and Urban League head Whitney Young."

Biography

Early life

James L. Farmer Jr. was born in Marshall,Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, to James L. Farmer Sr.

James Leonard Farmer Sr. (June 12, 1886 – May 14, 1961), known as J. Leonard Farmer, was an American author, theologian, and educator. He was a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South and an academic in early religious history as wel ...

and Pearl Houston, who were both educators. His father was a professor at Wiley College, a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

, and a Methodist minister with a Ph.D. in theology from Boston University. His mother, a homemaker, was a graduate of Florida's Bethune-Cookman Institute and a former teacher.

When Farmer was a young boy, about three or four, he wanted a Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Originally marketed as a temperance bar, temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, it was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pembe ...

when he was out in town with his mother. His mother had adamantly told him no, that he had to wait until they got home. Farmer wanted a Coke immediately and enviously watched another young boy go inside and buy one. His mother told him the other boy could buy the Coke at that store because he was white, but Farmer was a person of color and not allowed there. This defining, unjust moment was the first, but not the last, experience that Farmer remembered of segregation.

When Farmer was 10, Farmer's Uncle Fred, Aunt Helen, and cousin Muriel came down to visit from New York. They had no trouble getting a sleeping compartment on the train down but were worried about getting one on the way back. Farmer went to the train station with his dad. While his father convinced the manager to give his uncle a room in the sleeping car on the train, Farmer realized his dad was lying. Farmer was shocked to hear the lies, as his father was a minister. On the way back, his father told him, "I had to tell that lie about your Uncle Fred. That was the only way we could get the reservation. The Lord will forgive me." Still, Farmer was very upset that his father had to lie to get the bedroom on the train. This was when Farmer began to dedicate his life to ending segregation.

Farmer was a child prodigy; as a freshman in 1934 at the age of 14, he enrolled at Wiley College, a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

where his father was teaching in Marshall, Texas. He was selected as part of the debate team. Melvin B. Tolson, a professor of English, became his mentor.

Adult life

At the age of 21, Farmer was invited to theWhite House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

to talk with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

signed the invitation. Before the talk with the president, Mrs. Roosevelt talked to the group. Farmer took a liking to her immediately, and the two of them monopolized the conversation. When the group went in to talk to President Roosevelt, Mrs. Roosevelt followed and sat in the back. After the formalities were done, the young people were allowed to ask questions. Farmer said, "On your opening remarks you described Britain and France as champions of freedom. In light of their colonial policies in Africa, which give the lie to the principle, how can they be considered defenders?" The president tactfully avoided the question. She exclaimed, "Just a minute, you did not answer the question!" Although the president still did not answer the question as Farmer phrased it, Farmer was placated knowing that he had gotten the question out there.

Farmer earned a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree at Wiley College in 1938, and a Bachelor of Divinity

In Western universities, a Bachelor of Divinity or Baccalaureate in Divinity (BD or BDiv; la, Baccalaureus Divinitatis) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded for a course taken in the study of divinity or related disciplines, such as theolog ...

degree from Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

School of Religion in 1941. At Wiley, Farmer became anguished over segregation, recalling particular occasions of racism he had witnessed or suffered in his younger days. During the Second World War, Farmer had official status as a conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to objec ...

.

Inspired by Howard Thurman

Howard Washington Thurman (November 18, 1899 – April 10, 1981) was an American author, philosopher, theologian, mystic, educator, and civil rights leader. As a prominent religious figure, he played a leading role in many social justice movemen ...

, a professor of theology at Howard University, Farmer became interested in Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

-style pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace camp ...

.Arsenault, p. 29 Martin Luther King Jr. also studied this later and adopted many of its principles. Farmer started to think about how to stop racist practices in America while working at the Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

, which he joined after college.

During the 1950s, Farmer served as national secretary of the Student League for Industrial Democracy (SLID), the youth branch of the socialist League for Industrial Democracy The League for Industrial Democracy (LID) was founded as a successor to the Intercollegiate Socialist Society in 1921. Members decided to change its name to reflect a more inclusive and more organizational perspective.

Background Intercollegiate So ...

. SLID later became Students for a Democratic Society.

Farmer married Winnie Christie in 1945. Winnie became pregnant soon after they were married. Then she found a note from a girl in one of Farmer's coat pockets, an event that catalyzed the end of their marriage. She miscarried, and the couple divorced not long afterward.

A few years later, Farmer married Lula A. Peterson. She had been diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the patient's lymph nodes. The condition ...

, so the two were told not to have children because at that time pregnancy was thought to exacerbate cancer. Years later, they sought a second opinion. At that time, Lula was encouraged to try to have children. She had a miscarriage but then successfully had a daughter, Tami Lynn Farmer, born on February 14, 1959. A second daughter, Abbey Farmer, was born in 1962.

Founding CORE

James Farmer later recalled:I talked to A. J. Muste, executive director of theIn an interview withFellowship of Reconciliation The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...(FOR), about an idea to combat racial inequality. Muste found the idea promising but wanted to see it in writing. I spent months writing the memorandum making sure it was perfect. A. J. Muste wrote me back asking me about money to fund it and how they would get members. Finally, I was asked to propose my idea in front of the FOR National Council. In the end, FOR chose not to sponsor the group, but they gave me permission to start the group in Chicago. When Farmer got back to Chicago, the group began setting up the organization. The name they picked was CORE, the Committee of Racial Equality. The name was changed about a year later to theCongress of Racial Equality The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ....

Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, and literary critic and was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He founded the lit ...

in 1964 for the book ''Who Speaks for the Negro?

''Who Speaks for the Negro?'' is a 1965 book of interviews by Robert Penn Warren conducted with Civil Rights Movement activists. The book was reissued by Yale University Press in 2014. The Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderb ...

,'' Farmer described the founding principles of CORE as follows:

:1. that it involves the people themselves rather than experts,

:2. that it rejects segregation, and

:3. that it does so through nonviolent direct action.

Jack Spratt was a local diner in Chicago that would not serve colored people. CORE decided to do a large-scale sit in where they would occupy all available seats. Twenty-eight persons entered Jack Spratt in groups, with at least one black person in each group. No one who was served would eat until the black people were served, or they gave their plate to the black person nearest them. The other customers, already in the diner, did the same. The manager told them that they would serve the colored customers in the basement, but the group declined. Then it was proposed that all the colored people sit in the back corner and get served there, again the group declined. Finally the establishment called the police. When the police entered, they refused to kick the CORE group out. Having no other options, all patrons were served. Afterward, CORE did tests at Jack Spratt and found that the diner's policy had changed.

The White City Roller Skating Rink allowed only white patrons. Its staff made excuses to blacks as to why they could not enter. For example, white CORE members were allowed to enter the rink, but black members were refused because of "a private party". Having documented that the rink was lying about the circumstances, CORE decided to sue them. When the case went to trial, a state lawyer conducted the prosecution, rather than the county. The judge ruled in favor of the rink. Although the outcome of the case was a setback for CORE, the group was making a name for itself.

Freedom Rides

In 1961, Farmer, who was working for the

In 1961, Farmer, who was working for the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

, was reelected as the national director of CORE, as the civil rights movement was gaining power. Although the United States Supreme Court in '' Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia,'' 328 U.S. 373 (1946) had ruled that segregated interstate bus travel was unconstitutional, and reiterated that in ''Boynton v. Virginia

''Boynton v. Virginia'', 364 U.S. 454 (1960), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court.. The case overturned a judgment convicting an African American law student for trespassing by being in a restaurant in a bus terminal which was "white ...

'' (1960), interstate buses enforced segregation below the Mason–Dixon line (in southern states). Gordon Carey proposed the idea of a second Journey of Reconciliation

The Journey of Reconciliation, also called "First Freedom Ride", was a form of nonviolent direct action to challenge state segregation laws on interstate buses in the Southern United States.

Bayard Rustin and 18 other men and women were the ea ...

and Farmer jumped at the idea. This time the group planned to journey through the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

. Farmer coined a new name for the trip: the Freedom Ride.

They planned for a mixed race and gender group to test segregation on interstate buses. The group would be trained extensively on nonviolent tactics in Washington D.C. and embark on May 4, 1961: half by each of the two major carriers, Greyhound Bus Company and Trailways. They would ride through Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and finish in New Orleans on May 17. They planned to challenge segregated seating in bus stations and lunch rooms as well. For overnight stops they planned rallies and support from the black community, and scheduled talks at local churches or colleges.

On May 4, the participants began. The trip down through Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia went smoothly enough. The states knew about the trip and facilities either took down the "Colored" and "White Only" signs, or didn't enforce the segregation laws. Before the group made it to Alabama, the most dangerous part of the Freedom Ride, Farmer had to return home because his father died. In Alabama, the other riders were severely beaten and abused, narrowly escaping death when their bus was firebombed. With the bus destroyed, they flew to New Orleans instead of finishing the ride.

Diane Nash and other members of the Nashville Student Movement

The Nashville Student Movement was an organization that challenged racial segregation in Nashville, Tennessee during the Civil Rights Movement. It was created during workshops in nonviolence taught by James Lawson. The students from this or ...

and SNCC quickly recruited college students to restart the Freedom Ride where the first had left off. Farmer rejoined the group in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County, Alabama, Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the Gulf Coastal Plain, coas ...

. Doris Castle persuaded him to get on the bus at the last minute. The Riders were met with severe violence; in Birmingham the sheriff allowed local KKK members several minutes to attack the Riders, badly injuring a photographer. The violent reactions and events attracted national media attention.

Their efforts sparked a summer of similar rides by other Civil Rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

leaders and thousands of ordinary citizens. In Jackson, Mississippi, Farmer and the other riders were immediately jailed, but law enforcement prevented violence. The riders followed a "jail no bail" philosophy to try to fill the jails with protesters and attract media attention. From county and town jails, the riders were sent to harsher conditions at Parchman State Penitentiary. As the Freedom Rides were attacked by whites, news coverage became widespread, and included photographs, newspaper accounts, and motion pictures. The Congress of Racial Equality and segregation and civil rights became national issues. Farmer became well known as a civil rights leader. The Freedom Rides inspired Erin Gruwell

Erin Gruwell (born August 15, 1969) is an American teacher known for her unique teaching method, which led to the publication of ''The Freedom Writers Diary: How a Teacher and 150 Teens Used Writing to Change Themselves and the World Around Them ...

's teaching techniques and the Freedom Writers Foundation.

The following year, civil rights groups, supplemented by hundreds of college students from the North, worked with local activists in Mississippi on voter registration and education. James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964), was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers killed in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Schwerner and two co-workers, James C ...

, all of whom Farmer had helped recruit for CORE, disappeared during the Mississippi Freedom Summer. A full-scale FBI investigation aided by other law enforcement, found their murdered corpses buried in an earthen dam. The murders inspired the 1988 feature movie, ''Mississippi Burning

''Mississippi Burning'' is a 1988 American crime thriller film directed by Alan Parker that is loosely based on the 1964 murder investigation of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Mississippi. It stars Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as two F ...

.'' Years later, recalling the event, Farmer said, "Anyone who said he wasn't afraid during the civil rights movement was either a liar or without imagination. I think we were all scared. I was scared all the time. My hand didn't shake but inside I was shaking."

Later career

In 1963, Louisiana state troopers hunted him door to door for trying to organize protests. A funeral home director had Farmer play dead in the back of a hearse that carried him along back roads and out of town. He was arrested that August for disturbing the peace.

As the Director of CORE, Farmer was considered one of the " Big Six" of the

In 1963, Louisiana state troopers hunted him door to door for trying to organize protests. A funeral home director had Farmer play dead in the back of a hearse that carried him along back roads and out of town. He was arrested that August for disturbing the peace.

As the Director of CORE, Farmer was considered one of the " Big Six" of the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

who helped organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

in 1963. (The press also used the term "Big Four", ignoring John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

and Dorothy Height

Dorothy Irene Height (March 24, 1912 – April 20, 2010) was an African American civil rights and women's rights activist. She focused on the issues of African American women, including unemployment, illiteracy, and voter awareness. Height is c ...

.)

Growing disenchanted with emerging militancy and black nationalist sentiments in CORE, Farmer resigned as director in 1966. By that time, Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

, ending legal segregation, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights m ...

, authorizing federal enforcement of registration and elections.

Farmer took a teaching position at Lincoln University, a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

(HBCU) near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He also lectured around the country. In 1968, Farmer ran for U.S. Congress as a Liberal Party candidate backed by the Republican Party, but lost to Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita Chisholm ( ; ; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. Chisholm represented New York's 12th congressional distr ...

.

In 1969, the newly elected Republican President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

offered Farmer the position of Assistant Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a cabinet-level executive branch department of the U.S. federal government created to protect the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. Its motto is ...

(now Health and Human Services). The next year, frustrated by the Washington bureaucracy, Farmer resigned from the position.

Farmer retired from politics in 1971 but remained active, lecturing and serving on various boards and committees. He was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto II

''Humanist Manifesto II'', written in 1973 by humanists Paul Kurtz and Edwin H. Wilson, was an update to the previous ''Humanist Manifesto'' published in 1933, and the second entry in the '' Humanist Manifesto'' series. It begins with a state ...

in 1973. In 1975, he co-foundeFund for an Open Society

Its vision is a nation in which people live in stably integrated communities, where political and civic power is shared by people of different races and ethnicities. He led this organization until 1999. Farmer was named an honorary vice chairman of the

Democratic Socialists of America

The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is a Left-wing politics, left-wing Democratic Socialists of America#Tendencies within the DSA, multi-tendency Socialism, socialist and Labour movement, labor-oriented political organization. Its roots ...

.

He published his autobiography ''Lay Bare the Heart'' in 1985. In 1984, Farmer began teaching at Mary Washington College (now The University of Mary Washington

The University of Mary Washington (UMW) is a public liberal arts university in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Founded in 1908 as the Fredericksburg Teachers College, the institution was named Mary Washington College in 1938 after Mary Ball Wash ...

) in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg w ...

.

Farmer retired from his teaching position in 1998. He died on July 9, 1999, of complications from diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

in Fredericksburg, Virginia at the age of 79.

Legacy and honors

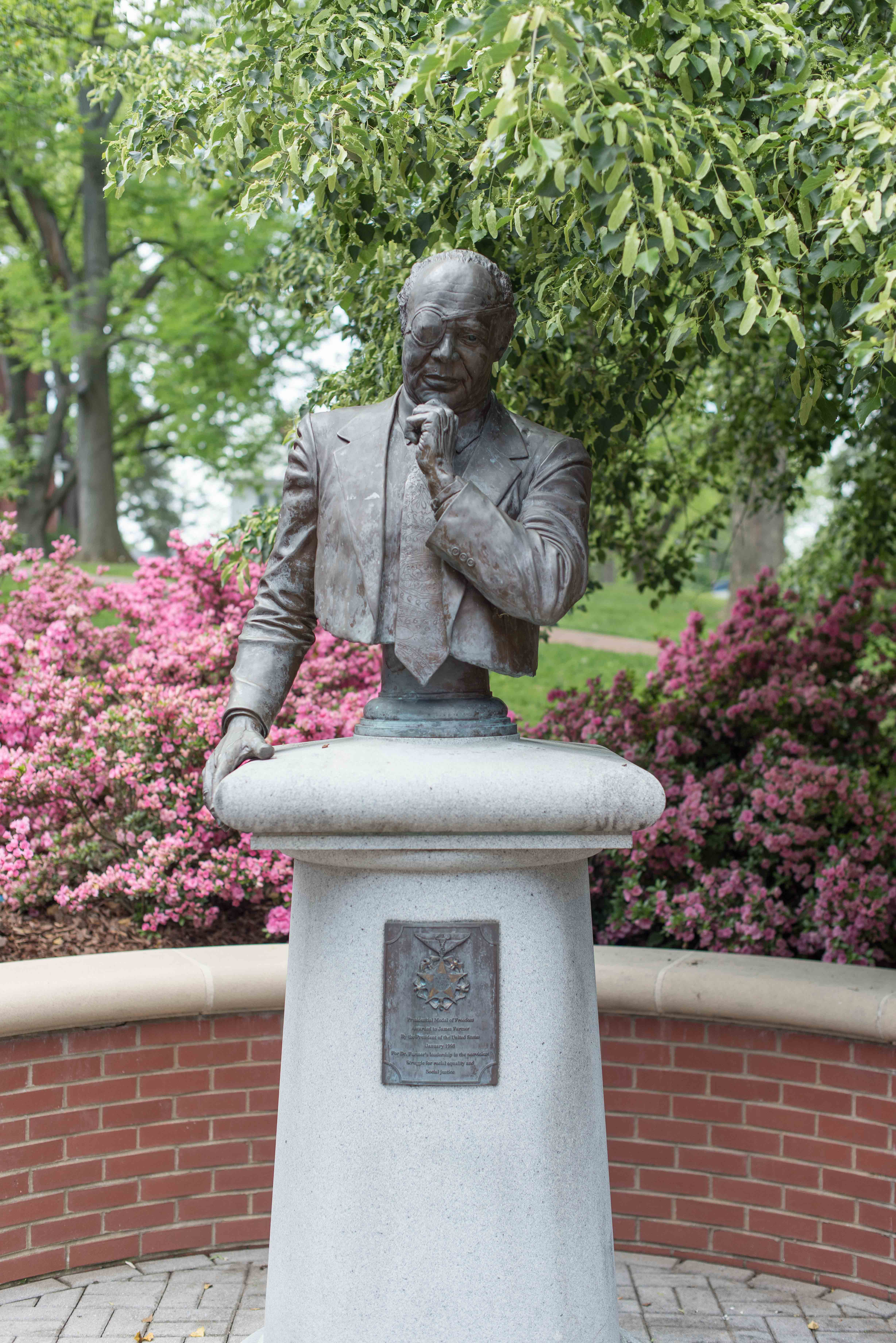

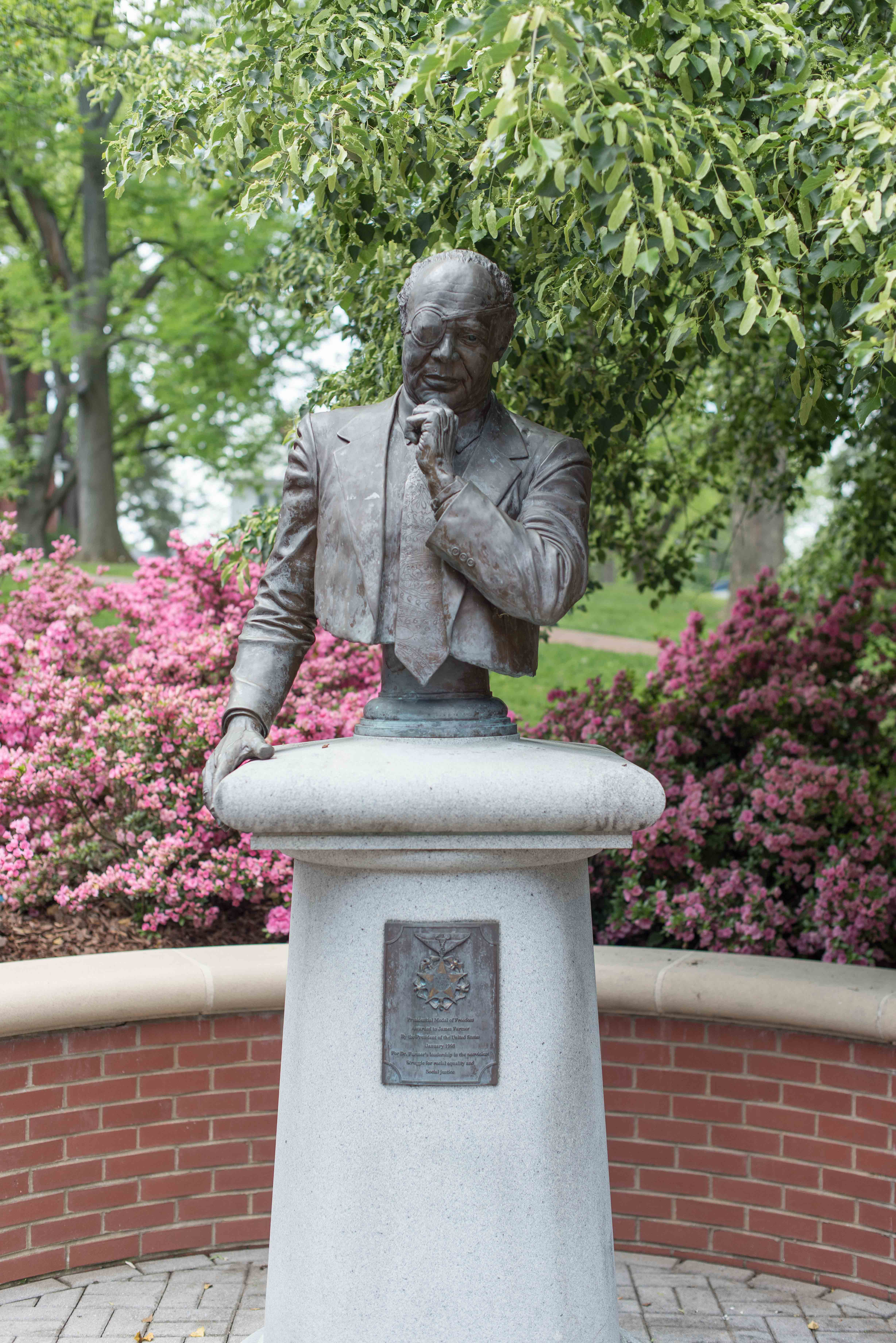

*A bust of Farmer was installed on the campus of Mary Washington College. *In 1987, Mary Washington College created the James Farmer Scholars program, to encourage minority students to enroll in college. *In 1995 the City of Marshall renamed Barney Street where Farmer grew up to James Farmer Street in honor of him and his father. *In 1998, PresidentBill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

awarded Farmer the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

.

*In 2012, the Library of Virginia

The Library of Virginia in Richmond, Virginia, is the library agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia. It serves as the archival agency and the reference library for Virginia's seat of government. The Library moved into a new building in 1997 and ...

named Farmer as one of its inaugural honorees in its "Strong Men and Women" series of African American trailblazers.

*In 2020, the University of Mary Washington

The University of Mary Washington (UMW) is a public liberal arts university in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Founded in 1908 as the Fredericksburg Teachers College, the institution was named Mary Washington College in 1938 after Mary Ball Wash ...

renamed the former Trinkle Hall to James Farmer Hall in honor of Dr. Farmer, who spent his final years as a professor of history at the university.

Works

* ''Lay Bare the Heart: An Autobiography of the Civil Rights Movement''. James Farmer, Penguin-Plume, 1986 *He wrote ''Religion and Racism'' but it has not been published. *''Freedom-When'' was published in 1965.George Houser

George Mills Houser (June 2, 1916 – August 19, 2015) was an American Methodist minister, civil rights activist, and activist for the independence of African nations. He served on the staff of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (1940s – 1950s). ...

about the founding of CORE. A conference at Bluffton College in Bluffton, Ohio, on October 22, 1992, ''Erasing the Color Line in the North'', explored CORE and its origins. Both Houser and Farmer attended. Academics and the participants unanimously agreed that the founders of CORE were James Farmer, George Houser and Bernice Fisher. The conference has been preserved on videotape available from Bluffton College.

See also

*List of civil rights leaders

Civil rights leaders are influential figures in the promotion and implementation of political freedom and the expansion of personal civil liberties and rights. They work to protect individuals and groups from political repressio ...

Notes

References

* Arsenault, Raymond. ''Freedom Riders 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.'' Oxford University Press, 2006. * Farmer, James. ''Lay Bare the Heart.'' Texas Christian University Press, 1985. *Frazier, Nishani (2017). ''Harambee City: Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism''. University of Arkansas Press. ."Who is James Farmer?"

University of Mary Washington

Further research

;Archival materialsUniversity of Texas Libraries. Accessed 2014.

James Farmer Lectures at University of Mary Washington

University of Mary Washington James Farmer Oral History Project

Oral History Interviews with James Farmer, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

FBI file on James Farmer

;Videos

Dr. James Farmer Jr. Civil Rights Documentary “The Good Fight” Fascinates And Educates, Movie Review from ShortFilmTexas.com

''You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!'' New Hampshire Public Television/American Public Television documentary of the Journey of Reconciliation

''Eyes on the Prize'' Blackside, Inc./PBS documentary of the Civil Rights Movement (Episode 3 is the Freedom Rides)

''Freedom Riders'' 50th anniversary documentary, PBS's American Experience

James Farmer

on the WGBH serie

The Ten O'Clock News

*

External links

Civil Rights Greensboro: James Farmer

Biography

at Encyclopedia Virginia *

Harambee City

Archival site incorporating big documents, maps, audio/visual materials related to CORE's work in black power and black economic development.

Image of the United Civil Rights Committee at a march against de facto school segregation in Los Angeles, California, 1963.

''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library

The Charles E. Young Research Library is one of the largest libraries on the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles in Westwood, Los Angeles, California. It initially opened in 1964, and a second phase of construction was completed ...

, University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the Californ ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Farmer, James L. Jr.

1920 births

1999 deaths

African-American activists

Activists for African-American civil rights

Members of the Democratic Socialists of America

Deaths from diabetes

Freedom Riders

Liberal Party of New York politicians

Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

Texas socialists

Virginia socialists

Washington, D.C., Republicans

Washington, D.C., socialists

Wiley College alumni

Competitive debaters