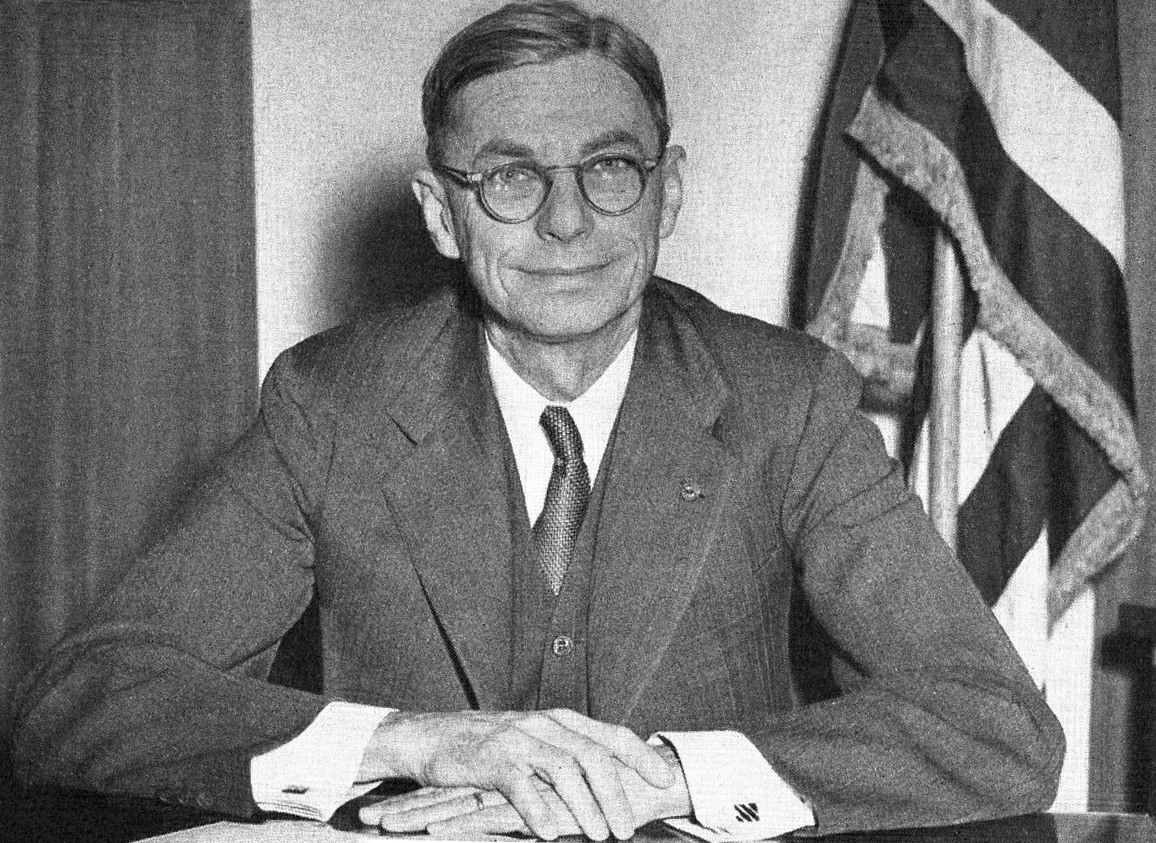

James Bryant Conant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American

Conant added new graduate degrees in education, history of science and public policy, and he introduced the

Conant added new graduate degrees in education, history of science and public policy, and he introduced the

By September 1948, the Red Scare began to take hold, and Conant called for a ban on hiring teachers who were communists, although not for the dismissal of those who had already been hired. A debate ensued over whether communist educators could teach apolitical subjects. Conant was a member of the Educational Policies Commission (EPC), a body to which he had been appointed in 1941. When it next met in March 1949, Conant's push for a ban was supported by the president of Columbia University, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower. The two found common ground in their belief in ideology-based education, which Conant called "democratic education". He did not see public education as a side effect of American democracy, but as one of its principal driving forces, and he disapproved of the public funding of denominational schools that he observed in Australia during his visit there in 1951. He called for increased federal spending on education, and higher taxes to redistribute wealth. His thinking was outlined in his books ''Education in a Divided World'' in 1948, and ''Education and Liberty'' in 1951. In 1952, he went further and endorsed the dismissal of academics who invoked the Fifth under questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A sign of Conant's declining influence occurred in 1950, when he was passed over for the post of President of the National Academy of Sciences in favor of

By September 1948, the Red Scare began to take hold, and Conant called for a ban on hiring teachers who were communists, although not for the dismissal of those who had already been hired. A debate ensued over whether communist educators could teach apolitical subjects. Conant was a member of the Educational Policies Commission (EPC), a body to which he had been appointed in 1941. When it next met in March 1949, Conant's push for a ban was supported by the president of Columbia University, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower. The two found common ground in their belief in ideology-based education, which Conant called "democratic education". He did not see public education as a side effect of American democracy, but as one of its principal driving forces, and he disapproved of the public funding of denominational schools that he observed in Australia during his visit there in 1951. He called for increased federal spending on education, and higher taxes to redistribute wealth. His thinking was outlined in his books ''Education in a Divided World'' in 1948, and ''Education and Liberty'' in 1951. In 1952, he went further and endorsed the dismissal of academics who invoked the Fifth under questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A sign of Conant's declining influence occurred in 1950, when he was passed over for the post of President of the National Academy of Sciences in favor of

In April 1951 Conant had been approached by the Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, about replacing

In April 1951 Conant had been approached by the Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, about replacing

Conant returned to the United States in February 1957, and moved to an apartment on the

Conant returned to the United States in February 1957, and moved to an apartment on the

1965 Audio Interview with James B. Conant by Stephane Groueff

Voices of the Manhattan Project * Correspondence between Conant and Linus Pauling. {{DEFAULTSORT:Conant, James Bryant 1893 births 1978 deaths Conant family Ambassadors of the United States to Germany American physical chemists Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellows of the Royal Institute of Chemistry Foreign Members of the Royal Society Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Harvard College alumni Harvard University faculty Honorary Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Manhattan Project people Medal for Merit recipients Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People from Boston Presidents of Harvard University U.S. Synthetic Rubber Program Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients 20th-century American diplomats Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery 20th-century American academics

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916. During World War I he served in the U.S. Army, working on the development of poison gases, especially Lewisite

Lewisite (L) (A-243) is an organoarsenic compound. It was once manufactured in the U.S., Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union for use as a chemical weapon, acting as a vesicant (blister agent) and lung irritant. Although the substance is colorless ...

. He became an assistant professor of chemistry at Harvard in 1919 and the Sheldon Emery Professor of Organic Chemistry in 1929. He researched the physical structures of natural products, particularly chlorophyll, and he was one of the first to explore the sometimes complex relationship between chemical equilibrium

In a chemical reaction, chemical equilibrium is the state in which both the reactants and products are present in concentrations which have no further tendency to change with time, so that there is no observable change in the properties of the ...

and the reaction rate of chemical processes. He studied the biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

of oxyhemoglobin providing insight into the disease methemoglobinemia

Methemoglobinemia, or methaemoglobinaemia, is a condition of elevated methemoglobin in the blood. Symptoms may include headache, dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea, poor muscle coordination, and blue-colored skin (cyanosis). Complications ...

, helped to explain the structure of chlorophyll, and contributed important insights that underlie modern theories of acid-base chemistry.

In 1933, Conant became the President of Harvard University with a reformist agenda that involved dispensing with a number of customs, including class rankings and the requirement for Latin classes. He abolished athletic scholarships, and instituted an " up or out" policy, under which scholars who were not promoted were terminated. His egalitarian vision of education required a diversified student body, and he promoted the adoption of the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and co-educational classes. During his presidency, women were admitted to Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

and Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

for the first time.

Conant was appointed to the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) in 1940, becoming its chairman in 1941. In this capacity, he oversaw vital wartime research projects, including the development of synthetic rubber and the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, which developed the first atomic bombs. On July 16, 1945, he was among the dignitaries present at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range

Alamogordo () is the seat of Otero County, New Mexico, United States. A city in the Tularosa Basin of the Chihuahuan Desert, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains and to the west by Holloman Air Force Base. The population ...

for the Trinity nuclear test, the first detonation of an atomic bomb, and was part of the Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on m ...

that advised President Harry S. Truman to use atomic bombs on Japan. After the war, he served on the Joint Research and Development Board (JRDC) that was established to coordinate burgeoning defense research, and on the influential General Advisory Committee (GAC) of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC); in the latter capacity he advised the president against starting a development program for the " hydrogen bomb."

In his later years at Harvard, Conant taught undergraduate courses on the history and philosophy of science, and wrote books explaining the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

to laymen. In 1953 he retired as President of Harvard and became the United States High Commissioner for Germany, overseeing the restoration of German sovereignty after World War II, and then was Ambassador to West Germany until 1957. On returning to the United States, he criticized the education system in works such as ''The American High School Today

''The American High School Today: A First Report to Interest Citizens'', better known as the Conant Report, is a 1959 assessment of American secondary schooling and 21 recommendations, authored by James B. Conant.

Publication

During his te ...

'' (1959), ''Slums and Suburbs'' (1961), and ''The Education of American Teachers'' (1963). Between 1965 and 1969, Conant, suffering from a heart condition, worked on his autobiography, ''My Several Lives'' (1970). He became increasingly infirm, suffered a series of stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

s in 1977, and died in a nursing home the following year.

Early life

James Bryant Conant was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts, on March 26, 1893, the third child and only son of James Scott Conant, a photoengraver, and his wife Jennett Orr (née Bryant). Conant was one of 35 boys who passed the competitive admission exam for the Roxbury Latin School in West Roxbury in 1904. He graduated near the top of his class in 1910. Encouraged by his science teacher, Newton H. Black, in September of that year he enteredHarvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

, where he studied physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistica ...

under Theodore W. Richards and organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J ...

under Elmer P. Kohler. He was also an editor of '' The Harvard Crimson''. He joined the Signet Society and Delta Upsilon

Delta Upsilon (), commonly known as DU, is a collegiate men's fraternity founded on November 4, 1834 at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is the sixth-oldest, all-male, college Greek-letter organization founded in North Americ ...

, and was initiated as a brother of the Omicron chapter of Alpha Chi Sigma in 1912. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

with his Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

in June 1913. He then went to work on his doctorate, which was an unusual double dissertation. The first part, supervised by Richards, concerned "The Electrochemical Behavior of Liquid Sodium Amalgams"; the second, supervised by Kohler, was "A Study of Certain Cyclopropane Derivatives". Harvard awarded Conant his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

degree in 1916.

In 1915, Conant entered into a business partnership with two other Harvard chemistry graduates, Stanley Pennock and Chauncey Loomis, to form the LPC Laboratories. They opened a plant in a one-story building in Queens, New York

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, where they manufactured chemicals used by the pharmaceutical industry like benzoic acid

Benzoic acid is a white (or colorless) solid organic compound with the formula , whose structure consists of a benzene ring () with a carboxyl () substituent. It is the simplest aromatic carboxylic acid. The name is derived from gum benzoin ...

that were selling at high prices on account of the interruption of imports from Germany due to World War I. In 1916, the departure of organic chemist Roger Adams created a vacancy at Harvard that was offered to Conant. Since he aspired to an academic career, Conant accepted the offer and returned to Harvard. On November 27, 1916, an explosion killed Pennock and two others and completely destroyed the plant. A contributing cause was Conant's faulty test procedures.

Following the United States declaration of war on Germany, Conant was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Sanitary Corps on September 22, 1917. He went to the Camp American University

The Navy Bomb Disposal School , was a World War II era U.S. naval training installation built on American University property in Washington, D.C.

Environmental impact

During World War II, American University allowed the U.S. Navy to use part o ...

, where he worked on the development of poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perma ...

es. Initially, his work concentrated on mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, ...

, but in May 1918, Conant took charge of a unit concerned with the development of lewisite

Lewisite (L) (A-243) is an organoarsenic compound. It was once manufactured in the U.S., Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union for use as a chemical weapon, acting as a vesicant (blister agent) and lung irritant. Although the substance is colorless ...

. He was promoted to major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

on July 20, 1918. A pilot plant was built, and then a full-scale production plant in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

, but the war ended before lewisite could be used in battle.

Conant was appointed an assistant professor of chemistry at Harvard in 1919. The following year he became engaged to Richards's daughter, Grace (Patty) Thayer Richards. They were married in the Appleton Chapel at Harvard on April 17, 1920, and had two sons, James Richards Conant, born in May 1923, and Theodore Richards Conant, born in July 1928.

Chemistry professor

Conant became an associate professor in 1924. In 1925, he visited Germany, then the heart of chemical research, for eight months. He toured the major universities and laboratories there and met many of the leading chemists, includingTheodor Curtius

''Geheimrat'' Julius Wilhelm Theodor Curtius (27 May 1857 – 8 February 1928) was professor of Chemistry at Heidelberg University and elsewhere. He published the Curtius rearrangement in 1890/1894 and also discovered diazoacetic acid, hydra ...

, Kazimierz Fajans, Hans Fischer, Arthur Hantzsch, Hans Meerwein

Hans Meerwein (May 20, 1879 in Hamburg, Germany – October 24, 1965 in Marburg, Germany) was a German chemist.

Several reactions and reagents bear his name, most notably the Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley reduction, the Wagner–Meerwein rearr ...

, Jakob Meisenheimer, Hermann Staudinger

Hermann Staudinger (; 23 March 1881 – 8 September 1965) was a German organic chemist who demonstrated the existence of macromolecules, which he characterized as polymers. For this work he received the 1953 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

He is also ...

, Adolf Windaus and Karl Ziegler

Karl Waldemar Ziegler (26 November 1898 – 12 August 1973) was a German chemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1963, with Giulio Natta, for work on polymers. The Nobel Committee recognized his "excellent work on organometallic compound ...

. After Conant returned to the United States, Arthur Amos Noyes

Arthur Amos Noyes (September 13, 1866 – June 3, 1936) was an American chemist, inventor and educator. He received a PhD in 1890 from Leipzig University under the guidance of Wilhelm Ostwald.

He served as the acting president of MIT between ...

made him an attractive offer to move to Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

. The President of Harvard, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, made a counter offer: immediate promotion to professor, effective September 1, 1927, with a salary of $7,000 (roughly equivalent to as of ) and a grant of $9,000 per annum for research. Conant accepted and stayed at Harvard. In 1929, he became the Sheldon Emery Professor of Organic Chemistry, and then, in 1931, the Chairman of the Chemistry Department.

Between 1928 and 1933, Conant published 55 papers. Much of his research, like his double thesis, combined natural product chemistry with physical organic chemistry. Based on his exploration of reaction rates in chemical equilibria, Conant was one of the first to recognise that the kinetics

Kinetics ( grc, κίνησις, , kinesis, ''movement'' or ''to move'') may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Kinetics (physics), the study of motion and its causes

** Rigid body kinetics, the study of the motion of rigid bodies

* Chemical kin ...

of these systems is sometimes straightforward and simple, yet quite complex in other cases. Conant studied the effect of haloalkane structure on the rate of substitution

Substitution may refer to:

Arts and media

*Chord substitution, in music, swapping one chord for a related one within a chord progression

*Substitution (poetry), a variation in poetic scansion

* "Substitution" (song), a 2009 song by Silversun Pic ...

with inorganic iodide salts which, together with earlier work, led to what is now known as either the Conant-Finkelstein reaction or more commonly simply the Finkelstein reaction. A recent application of this reaction involved the preparation of an iodinated polyvinyl chloride from regular PVC. A combination of Conant's work on the kinetics of hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate organic ...

and George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

's work on the enthalpy changes of these reactions supported the later development of the theory of hyperconjugation.

Conant's investigations helped in the development of a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of acids and bases. He investigated the properties of certain acids which were many times stronger than mineral acid solutions in water. Conant christened them "superacid

In chemistry, a superacid (according to the classical definition) is an acid with an acidity greater than that of 100% pure sulfuric acid (), which has a Hammett acidity function (''H''0) of −12. According to the modern definition, a superaci ...

s" and laid the foundation for the development of the Hammett acidity function

The Hammett acidity function (''H''0) is a measure of acidity that is used for very concentrated solutions of strong acids, including superacids. It was proposed by the physical organic chemist Louis Plack Hammett and is the best-known acidity fu ...

. These investigations used acetic acid as the solvent

A solvent (s) (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for ...

and demonstrated that sodium acetate behaves as a base under these conditions. This observation is consistent with Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory

The Brønsted–Lowry theory (also called proton theory of acids and bases) is an acid–base reaction theory which was proposed independently by Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry in 1923. The fundamental concept of this theory ...

(published in 1923) but cannot be explained under older Arrhenius theory approaches. Later work with George Wheland and extended by William Kirk McEwen looked at the properties of hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

s as very weak acids, including acetophenone, phenylacetylene

Phenylacetylene is an alkyne hydrocarbon containing a phenyl group. It exists as a colorless, viscous liquid. In research, it is sometimes used as an analog for acetylene; being a liquid, it is easier to handle than acetylene gas.

Preparation

In ...

, fluorene and diphenylmethane. Conant can be considered alongside Brønsted, Lowry, Lewis, and Hammett as a developer of modern understanding of acids and bases.

Between 1929 and his retirement from chemical research in 1933, Conant published papers in ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

'', ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'', and the ''Journal of the American Chemical Society

The ''Journal of the American Chemical Society'' is a weekly peer-reviewed scientific journal that was established in 1879 by the American Chemical Society. The journal has absorbed two other publications in its history, the ''Journal of Analyti ...

'' about chlorophyll and its structure. Though the complete structure eluded him, his work did support and contribute to Nobel laureate Hans Fischer's ultimate determination of the structure in 1939. Conant's work on chlorophyll was recognised when he was inducted as a foreign Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

on May 2, 1941. He also published three papers describing the polymerisation of isoprene to prepare synthetic rubber.

Another line of research involved the biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

of the hemoglobin-oxyhemoglobin system. Conant ran a series of experiments with electrochemical oxidation and reduction, following in the footsteps of the famous German chemist and Nobel laureate Fritz Haber. He determined that the iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

centre in methemoglobin is a ferric (FeIII) centre, unlike the ferrous (FeII) centre found in normal hemoglobin, and this difference in oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. C ...

is the cause of methemoglobinemia

Methemoglobinemia, or methaemoglobinaemia, is a condition of elevated methemoglobin in the blood. Symptoms may include headache, dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea, poor muscle coordination, and blue-colored skin (cyanosis). Complications ...

, a medical condition which causes tissue hypoxia

Hypoxia is a condition in which the body or a region of the body is deprived of adequate oxygen supply at the tissue level. Hypoxia may be classified as either '' generalized'', affecting the whole body, or ''local'', affecting a region of the bo ...

.

Conant wrote a chemistry textbook with his former science teacher Black, entitled ''Practical Chemistry'', which was published in 1920, with a revised edition in 1929. This was superseded in 1937 by their ''New Practical Chemistry'', which in turn had a revised edition in 1946. The text proved a popular one; it was adopted by 75 universities, and Conant received thousands of dollars in royalties. For his accomplishments in chemistry, he was awarded the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

's Nichols Medal in 1932, Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's Chandler Medal in 1932, and the American Chemical Society's highest honor, the Priestley Medal

The Priestley Medal is the highest honor conferred by the American Chemical Society (ACS) and is awarded for distinguished service in the field of chemistry. Established in 1922, the award is named after Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen ...

, in 1944. He also received the society's Charles Lathrop Parsons Award in 1955, for public service. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1924, and the National Academy of Sciences in 1929. Notable students of Conant's included Paul Doughty Bartlett, George Wheland, and Frank Westheimer. In 1932 he was also honored by membership of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

The German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (german: Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina – Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften), short Leopoldina, is the national academy of Germany, and is located in Halle (Saale). Founde ...

.

After some months of lobbying and discussion, Harvard's ruling body, the Harvard Corporation, announced on May 8, 1933, that it had elected Conant as the next President of Harvard. Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is best known as the defining figure of the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which today has found applica ...

, Harvard's eminent professor of philosophy disagreed with the decision, declaring, "The Corporation should not have elected a chemist to the Presidency." "But," Corporation member Grenville Clark

Grenville Clark (November 5, 1882 – January 13, 1967) was a 20th-century American Wall Street lawyer, co-founder of Root Clark & Bird (later Dewey Ballantine, then Dewey & LeBoeuf), member of the Harvard Corporation, co-author of the book '' ...

reminded him, " Eliot was a chemist, and our best president too." "I know," replied Whitehead, "but Eliot was a ''bad'' chemist." Clark was very much responsible for Conant's election.

President of Harvard

On October 9, 1933, Conant became the President of Harvard University with a low-key installation ceremony in the Faculty Room of University Hall. This set the tone for Conant's presidency as one of informality and reform. At his inauguration, he accepted the charter and seal presented to John Leverett the Younger in 1707, but dropped a number of other customs, including the singing of ''Gloria Patri

The Gloria Patri, also known as the Glory Be to the Father or, colloquially, the Glory Be, is a doxology, a short hymn of praise to God in various Christian liturgies. It is also referred to as the Minor Doxology ''(Doxologia Minor)'' or Les ...

'' and the Latin Oration. While, unlike some other universities, Harvard did not require Greek or Latin for entrance, they were worth double credits towards admission, and students like Conant who had studied Latin were awarded an A.B. degree while those who had not, received an S.B. One of his first efforts at reform was to attempt to abolish this distinction, which took over a decade to accomplish. But in 1937 he wrote:

Other reforms included the abolition of class rankings and athletic scholarships, but his first, longest and most bitter battle was over tenure reform, shifting to an " up or out" policy, under which scholars who were not promoted were terminated. A small number of extra-departmental positions was set aside for outstanding scholars. This policy led junior faculty to revolt, and nearly resulted in Conant's dismissal in 1938. Conant was fond of saying: "Behold the turtle. It makes progress only when it sticks its neck out."

Conant added new graduate degrees in education, history of science and public policy, and he introduced the

Conant added new graduate degrees in education, history of science and public policy, and he introduced the Nieman Fellowship

The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University awards multiple types of fellowships.

Nieman Fellowships for journalists

A Nieman Fellowship is an award given to journalists by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard Universit ...

for journalists to study at Harvard, the first of which was awarded in 1939. He supported the "meatballs", as lower class students were called. He instituted the Harvard national scholarships for underprivileged students. Dudley House was opened as a place where non-resident students could stay. Conant asked two of his assistant deans, Henry Chauncey Henry Chauncey (February 9, 1905 – December 3, 2002) was a founder and the first president of the Educational Testing Service (ETS).

He graduated from Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy L ...

and William Bender, to determine whether the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) was a good measure of academic potential. When they reported that it was, Conant adopted it. He waged a ten-year campaign for the consolidation of testing services, which resulted in the creation of the Educational Testing Service in 1946, with Chauncey as its director. Theodore H. White

Theodore Harold White (, May 6, 1915 – May 15, 1986) was an American political journalist and historian, known for his reporting from China during World War II and the ''Making of the President'' series.

White started his career reporting for ...

, a Boston Jewish "meatball" who received a personal letter of introduction from Conant so that he could report on the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

, noted that "Conant was the first president to recognize that meatballs were Harvard men too."

Instead of conducting separate but identical undergraduate courses for Harvard students and students from Radcliffe College

Radcliffe College was a women's liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and functioned as the female coordinate institution for the all-male Harvard College. Considered founded in 1879, it was one of the Seven Sisters colleges and h ...

, Conant instituted co-educational classes. It was during his presidency that the first class of women were admitted to Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

in 1945, and Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

in 1950. Lowell, Conant's predecessor, had imposed a 15 percent quota on Jewish students in 1922, something Conant had voted to support. This quota was later substituted with geographic distribution preferences, having the same effect of limiting Jewish admission. In the words of historians Morton and Phyllis Keller, "Conant's pro-quota position in the early 1920s, his preference for more students from small towns and cities and the South and West, and his cool response to the plight of the Jewish academic refugees from Hitler suggest that he shared the mild antisemitism common to his social group and time. But his commitment to meritocracy made him more ready to accept able Jews as students and faculty."

In 1934, Harvard-educated German businessman Ernst Hanfstaengl attended the 25th anniversary reunion of his class of 1909, and gave a number of speeches, including the 1934 commencement address. Hanfstaengl wrote out a check for (roughly equivalent to as of ) to Conant for a scholarship to enable an outstanding Harvard student to study for a year in Germany. The President and Fellows of Harvard College rejected the offer due to Hanfstaengl's Nazi associations. When the issue of Hanfstaengl's scholarship came up again in 1936, Conant turned the money down a second time. Hanfstaengl's presence on campus prompted a series of anti-Nazi demonstrations, in which a number of Harvard and MIT students were arrested. Conant made a personal plea for clemency that resulted in two girls being acquitted, but six boys and a girl were sentenced to six months in prison.

When the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

awarded an honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad h ...

in 1934 to American legal scholar and Dean of Harvard Law School Roscoe Pound

Nathan Roscoe Pound (October 27, 1870 – June 30, 1964) was an American legal scholar and educator. He served as Dean of the University of Nebraska College of Law from 1903 to 1911 and Dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1936. He was a memb ...

, who had toured Germany earlier that year and made no secret of his admiration for the Nazi regime, Conant refused to order Pound not to accept it, and attended the informal award ceremony at Harvard where Pound was presented with the degree by Hans Luther, the German ambassador to the United States. While Conant declined to participate in the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars, Harvard awarded honorary degrees to two notable displaced scholars, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

, in 1935. What Conant feared most was disruption to Harvard's tercentennial celebrations in 1936, but there was no trouble, despite the presence of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, and a Harvard graduate of the class of 1904, whom many Harvard graduates regarded as a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and a class traitor. It was only with difficulty that Lowell was persuaded to be presiding officer at an event at which Roosevelt spoke.

An incident took place during the 1941 Harvard–Navy lacrosse game

The Harvard-Navy lacrosse game of 1941 was an intercollegiate lacrosse game played in Annapolis, Maryland, between the Harvard University Crimson and the United States Naval Academy Midshipmen on April 4, 1941. Before the game, the Naval Academy ...

, when the Harvard Crimson men's lacrosse

The Harvard Crimson men's lacrosse team represents Harvard University in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I men's lacrosse. Harvard competes as a member of the Ivy League and plays its home games at Cumnock Turf and Harva ...

team attempted to field a player of African-American descent. The Navy Midshipmen men's lacrosse

The Navy Midshipmen men's lacrosse team represents the United States Naval Academy in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I men's lacrosse. Navy currently competes as a member of the Patriot League and play their home gam ...

team's coach then refused to field his team. Harvard's athletic director, William J. Bingham, overruled his lacrosse coach, and had the player, Lucien Victor Alexis, Jr., sent back to Cambridge on a train. Conant subsequently apologized to the Commandant of Midshipmen. After serving in World War II, Alexis was refused admittance to Harvard Medical School on the grounds that, as the only black student, he would have no one to room with. Alexis graduated from Harvard Business School instead.

National Defense Research Committee

In June 1940, with World War II already raging in Europe,Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

, the director of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, recruited Conant to the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), although he remained president of Harvard. Bush envisaged the NDRC as bringing scientists together to "conduct research for the creation and improvement of instrumentalities, methods and materials of warfare." Although the United States had not yet entered the war, Conant was not alone in his conviction that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

had to be stopped, and that the United States would inevitably become embroiled in the conflict. The immediate task, as Conant saw it, was therefore to organize American science for war. He became head of the NDRC's Division B, the division responsible for bombs, fuels, gases and chemicals. On June 28, 1941, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8807, which created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), with Bush as its director. Conant succeeded Bush as Chairman of the NDRC, which was subsumed into the OSRD. Roger Adams, a contemporary of Conant's at Harvard in the 1910s, succeeded him as head of Division B. Conant became the driving force of the NDRC on personnel and policy matters. The NDRC would work hand in hand with the Army and Navy's research efforts, supplementing rather than supplanting them. It was specifically charged with investigating nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

.

In February 1941, Roosevelt sent Conant to Britain as head of a mission that also included Frederick L. Hovde

Frederick Lawson Hovde (7 February 1908 – 1 March 1983) was an American chemical engineer, researcher, educator and president of Purdue University.

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, Hovde received his Bachelor of Chemical Engineering from the Unive ...

from Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and ...

and Carroll L. Wilson from MIT, to evaluate the research being carried out there and the prospects for cooperation. The 1940 Tizard Mission had revealed that American technology was some years behind that of Britain in many fields, most notably radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

, and cooperation was eagerly sought. Conant had lunch with Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and Frederick Lindemann

Frederick Alexander Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, ( ; 5 April 18863 July 1957) was a British physicist who was prime scientific adviser to Winston Churchill in World War II.

Lindemann was a brilliant intellectual, who cut through bureau ...

, his leading scientific adviser, and an audience with King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

at Buckingham Palace. At a subsequent meeting, Lindemann told Conant about British progress towards developing an atomic bomb. What most impressed Conant was the British conviction that it was feasible. That the British program was ahead of the American one raised the possibility in Conant's mind that the German nuclear energy project might be even further ahead, as Germany was generally acknowledged to be a world leader in nuclear physics. Later that year, Churchill, as Chancellor of the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, conferred an honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

degree on Conant ''in absentia''.

Conant subsequently moved to restrict cooperation with Britain on nuclear energy, particularly its post-war aspects, and became involved in heated negotiations with Wallace Akers, the representative of Tube Alloys, the British atomic project. Conant's tough stance, under which the British were excluded except where their assistance was vital, resulted in British retaliation, and a complete breakdown of cooperation. His objections were swept aside by Roosevelt, who brokered the 1943 Quebec Agreement with Churchill, that restored full cooperation. After the Quebec Conference, Churchill visited Conant at Harvard, where Conant returned the 1941 gesture and presented Churchill with an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. After the United States entered the war in December 1941, the OSRD handed the atomic bomb project, better known as the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, over to the Army, with Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves as project director. A meeting that included Conant decided Groves should be answerable to a small committee called the Military Policy Committee, chaired by Bush, with Conant as his alternate. Thus, Conant remained involved in the administration of the Manhattan Project at its highest levels.

In August 1942, Roosevelt appointed Conant to the Rubber Survey Committee. Chaired by Bernard M. Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in ...

, a trusted adviser and confidant of Roosevelt, the committee was tasked with reviewing the synthetic rubber program. Corporations used patent laws to restrict competition and stifle innovation. When the Japanese occupation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak, followed by the Japanese occupation of Indonesia

The Empire of Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) during World War II from March 1942 until after the end of the war in September 1945. It was one of the most crucial and important periods in modern Indonesian history.

In ...

, cut off 90 percent of the supply of natural rubber, the rubber shortage became a national scandal, and the development of synthetic substitutes, an urgent priority. Baruch dealt with the difficult political issues; Conant concerned himself with the technical ones. There were a number of different synthetic rubber products to choose from. In addition to DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

's neoprene, Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

had licensed German patents for a copolymer

In polymer chemistry, a copolymer is a polymer derived from more than one species of monomer. The polymerization of monomers into copolymers is called copolymerization. Copolymers obtained from the copolymerization of two monomer species are ...

called Buna-N

Nitrile rubber, also known as nitrile butadiene rubber, NBR, Buna-N, and acrylonitrile butadiene rubber, is a synthetic rubber derived from acrylonitrile (ACN) and butadiene. Trade names include Perbunan, Nipol, Krynac and Europrene. This rubber is ...

and a related product, Buna-S. None had been manufactured on the scale now required, and there was pressure from agricultural interests to choose a process which involved making raw materials from farm products. The Rubber Survey Committee made a series of recommendations, including the appointment of a rubber director, and the construction and operation of 51 factories to supply the materials needed for synthetic rubber production. Technical problems dogged the program through 1943, but by late 1944 plants were in operation with an annual capacity of over a million tons, most of which was Buna-S.

In May 1945, Conant became part of the Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on m ...

that was formed to advise the new president, Harry S. Truman on nuclear weapons. The Interim Committee decided that the atomic bomb should be used against an industrial target in Japan as soon as possible and without warning. On July 16, 1945, Conant was among the dignitaries present at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range

Alamogordo () is the seat of Otero County, New Mexico, United States. A city in the Tularosa Basin of the Chihuahuan Desert, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains and to the west by Holloman Air Force Base. The population ...

for the Trinity nuclear test, the first detonation of an atomic bomb. After the war, Conant became concerned about growing criticism in the United States of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by figures like Norman Cousins

Norman Cousins (June 24, 1915 – November 30, 1990) was an American political journalist, author, professor, and world peace advocate.

Early life

Cousins was born to Jewish immigrant parents Samuel Cousins and Sarah Babushkin Cousins, in West ...

and Reinhold Niebuhr. He played an important behind-the-scenes role in shaping public opinion by instigating and then editing an influential February 1947 '' Harper's'' article entitled "The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb". Written by former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

with the help of McGeorge Bundy, the article stressed that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were used to avoid the possibility of "over a million casualties", from a figure found in the estimates given to the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

by its Joint Planning Staff in 1945.

Cold War

TheAtomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act ru ...

replaced the wartime Manhattan Project with the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on January 1, 1947. The Act also established the General Advisory Committee (GAC) within the AEC to provide it with scientific and technical advice. It was widely expected that Conant would chair the GAC, but the position went to Robert Oppenheimer, the wartime director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

that had designed and developed the first atomic bombs. At the same time, the Joint Research and Development Board (JRDC) was established to coordinate defense research, and Bush asked Conant to head its atomic energy subcommittee, on which Oppenheimer also served. When the new AEC chairman David E. Lilienthal

David Eli Lilienthal (July 8, 1899 – January 15, 1981) was an American attorney and public administrator, best known for his Presidential Appointment to head Tennessee Valley Authority and later the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He had p ...

raised security concerns about Oppenheimer's relationships with communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

s, including Oppenheimer's brother Frank Oppenheimer

Frank Friedman Oppenheimer (August 14, 1912 – February 3, 1985) was an American particle physicist, cattle rancher, professor of physics at the University of Colorado, and the founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

A younger brother ...

, his wife Kitty and his former girlfriend Jean Tatlock

Jean Frances Tatlock (February 21, 1914 – January 4, 1944) was an American psychiatrist and physician. She was a member of the Communist Party of the United States of America and was a reporter and writer for the party's publication ''Western ...

, Bush and Conant reassured Lilienthal that they had known about it when they had placed Oppenheimer in charge at Los Alamos in 1942. With such expressions of support, AEC issued Oppenheimer a Q clearance

Q clearance or Q access authorization is the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) security clearance required to access Top Secret Restricted Data, Formerly Restricted Data, and National Security Information, as well as Secret Restricted Data. Restr ...

, granting him access to atomic secrets.

By September 1948, the Red Scare began to take hold, and Conant called for a ban on hiring teachers who were communists, although not for the dismissal of those who had already been hired. A debate ensued over whether communist educators could teach apolitical subjects. Conant was a member of the Educational Policies Commission (EPC), a body to which he had been appointed in 1941. When it next met in March 1949, Conant's push for a ban was supported by the president of Columbia University, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower. The two found common ground in their belief in ideology-based education, which Conant called "democratic education". He did not see public education as a side effect of American democracy, but as one of its principal driving forces, and he disapproved of the public funding of denominational schools that he observed in Australia during his visit there in 1951. He called for increased federal spending on education, and higher taxes to redistribute wealth. His thinking was outlined in his books ''Education in a Divided World'' in 1948, and ''Education and Liberty'' in 1951. In 1952, he went further and endorsed the dismissal of academics who invoked the Fifth under questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A sign of Conant's declining influence occurred in 1950, when he was passed over for the post of President of the National Academy of Sciences in favor of

By September 1948, the Red Scare began to take hold, and Conant called for a ban on hiring teachers who were communists, although not for the dismissal of those who had already been hired. A debate ensued over whether communist educators could teach apolitical subjects. Conant was a member of the Educational Policies Commission (EPC), a body to which he had been appointed in 1941. When it next met in March 1949, Conant's push for a ban was supported by the president of Columbia University, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower. The two found common ground in their belief in ideology-based education, which Conant called "democratic education". He did not see public education as a side effect of American democracy, but as one of its principal driving forces, and he disapproved of the public funding of denominational schools that he observed in Australia during his visit there in 1951. He called for increased federal spending on education, and higher taxes to redistribute wealth. His thinking was outlined in his books ''Education in a Divided World'' in 1948, and ''Education and Liberty'' in 1951. In 1952, he went further and endorsed the dismissal of academics who invoked the Fifth under questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A sign of Conant's declining influence occurred in 1950, when he was passed over for the post of President of the National Academy of Sciences in favor of Detlev Bronk

Detlev Wulf Bronk (August 13, 1897 – November 17, 1975) was a prominent American scientist, educator, and administrator. He is credited with establishing biophysics as a recognized discipline. Bronk served as president of Johns Hopkins Universi ...

, the President of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

, after a "revolt" by scientists unhappy with Conant. The GAC was enormously influential throughout the late 1940s, but the opposition of Oppenheimer and Conant to the development of the hydrogen bomb, only to be overridden by Truman in 1950, diminished its stature. It was reduced further when Oppenheimer and Conant were not reappointed when their terms expired in 1952, depriving the GAC of its two best-known members. Conant was appointed to the National Science Board, which administered the new National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National ...

, and was elected its chairman, but this body had little financial or political clout. In April 1951, Truman appointed Conant to the Science Advisory Committee, but it would not develop into an influential body until the Eisenhower administration.

Conant's experience with the Manhattan Project convinced him that the public needed a better understanding of science, and he moved to revitalize the history and philosophy of science program at Harvard. He took the lead personally by teaching a new undergraduate course, Natural Science 4, "On Understanding Science". His course notes became the basis for a book of the same name, published in 1948. In 1952, he began teaching another undergraduate course, Philosophy 150, "A Philosophy of Science". In his teachings and writing on the philosophy of science, he drew heavily on those of his Harvard colleague Willard Van Orman Quine

Willard Van Orman Quine (; known to his friends as "Van"; June 25, 1908 – December 25, 2000) was an American philosopher and logician in the analytic tradition, recognized as "one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century" ...

. Conant contributed four chapters to the 1957 ''Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science'', including an account of the overthrow of the phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''bur ...

. In 1951, he published ''Science and Common Sense'', in which he attempted to explain the ways of scientists to laymen. Conant's ideas about scientific progress would come under attack by his own protégés, notably Thomas Kuhn in '' The Structure of Scientific Revolutions''. Conant commented on Kuhn's manuscript in draft form.

High Commissioner

In April 1951 Conant had been approached by the Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, about replacing

In April 1951 Conant had been approached by the Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, about replacing John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and a presidential advisor. He served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry Stimson, helping deal with issues such as German sa ...

as United States High Commissioner for Germany, but had declined. However, after Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, Conant was again offered the job by the new Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, and this time he accepted. At the Harvard Board of Overseers The Harvard Board of Overseers (more formally The Honorable and Reverend the Board of Overseers) is one of Harvard University's two governing boards. Although its function is more consultative and less hands-on than the President and Fellows of Ha ...

meeting on January 12, 1952, Conant announced that he would retire in September 1953 after twenty years at Harvard, having reached the pension age of sixty.

In Germany, there were major issues to be decided. Germany was still occupied by the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain and France. Dealing with the wartime allies was a major task for the high commissioner. West Germany, made up of the zones occupied by the three western powers, had been granted control of its own affairs, except for defense and foreign policy, in 1949. While most Germans wanted a neutral and reunited Germany, the Eisenhower administration sought to reduce its defense spending by rearming Germany and replacing American troops with Germans. Meanwhile, the House Un-American Activities Committee slammed Conant's staff as communist sympathizers and called for books by communist authors held in United States Information Agency (USIA) libraries in Germany to be burned.

The first crisis to occur on Conant's watch was the uprising of 1953 in East Germany. This brought the reunification issue to the fore. Konrad Adenauer's deft handling of the issue enabled him to handily win re-election as Chancellor of West Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ger ...

in September, but this also strengthened his hand in negotiations with Conant. Adenauer did not want his country to become a bargaining chip between the United States and the Soviet Union, nor did he want it to become a nuclear battlefield, a prospect raised by the arrival of American tactical nuclear weapons in 1953 as part of the Eisenhower administration's New Look policy. Conant lobbied for the European Defense Community

The Treaty establishing the European Defence Community, also known as the Treaty of Paris, is an unratified treaty signed on 27 May 1952 by the six 'inner' countries of European integration: the Benelux countries, France, Italy, and West Germa ...

, which would have established a pan-European military. This seemed to be the only way that German rearmament would be accepted, but opposition from France killed the plan. In what Conant considered a minor miracle, France's actions cleared the way for West Germany to become part of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

with its own army.

At noon on May 6, 1955, Conant, along with the high commissioners from Britain and France, signed the documents ending Allied control of West Germany, admitting it to NATO, and allowing it to rearm. The office of the United States High Commissioner was abolished and Conant became instead the first United States Ambassador to West Germany. His role was now to encourage West Germany to build up its forces, while reassuring the Germans that doing so would not result in a United States withdrawal. Being fluent in German, Conant was able to give speeches to German audiences. He paid numerous visits to German educational and scientific organizations.

While high commissioner, Conant approved the release of many major and other German war criminals after serving only a fraction of their sentences, against protests from American political leaders and veterans' organizations (some of those sentenced had murdered American prisoners), accusing him of "moral amnesia". Such criticism continued when as ambassador he supported the West German government's leniency toward former Nazis.

Later life

Conant returned to the United States in February 1957, and moved to an apartment on the

Conant returned to the United States in February 1957, and moved to an apartment on the Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 96th Street to the north, the East River to the east, 59th Street to the south, and Central Park/Fifth Avenue to the we ...

of New York. Between 1957 and 1965, the Carnegie Corporation of New York gave him over a million dollars to write studies of education. In 1959 he published ''The American High School Today

''The American High School Today: A First Report to Interest Citizens'', better known as the Conant Report, is a 1959 assessment of American secondary schooling and 21 recommendations, authored by James B. Conant.

Publication

During his te ...

'', better known as the Conant Report. This became a best seller, resulting in Conant's appearance on the cover of ''Time'' magazine on September 14, 1959. In it, Conant called for a number of reforms, including the consolidation of high schools into larger bodies that could offer a broader range of curriculum choices. Although it was slammed by critics of the American system, who hoped for a system of education based on the European model, it did lead to a wave of reforms across the country. His subsequent ''Slums and Suburbs'' in 1961 was far more controversial in its treatment of racial issues. Regarding busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in ...

as impractical, Conant urged Americans "to accept ''de facto'' segregated schools". This did not go over well with civil rights groups, and by 1964 Conant was forced to admit that he had been wrong. In ''The Education of American Teachers'' in 1963, Conant found much to criticize about the training of teachers. Most controversial was his defense of the arrangement by which teachers were certified by independent bodies rather than the teacher training colleges.

President Lyndon Johnson presented Conant with the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

, with special distinction, on December 6, 1963. He had been selected for the award by President John F. Kennedy, but the ceremony had been delayed, and went ahead after Kennedy's assassination in November 1963. In February 1970, President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

presented Conant with the Atomic Pioneers Award from the Atomic Energy Commission. Other awards that Conant received during his long career included being made a Commander of Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

by France in 1936 and an Honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

by Britain in 1948, and he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or , BVO) is the only federal decoration of Germany. It is awarded for special achievements in political, economic, cultural, intellect ...

in 1957. He was also awarded over 50 honorary degrees, and was posthumously inducted into the Alpha Chi Sigma Hall of Fame in 2000.

Between 1965 and 1969, Conant, suffering from a heart condition, worked on his biography, ''My Several Lives''. He became increasingly infirm, and suffered a series of stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

s in 1977. He died in a nursing home in Hanover, New Hampshire

Hanover is a town located along the Connecticut River in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. As of the 2020 census, its population was 11,870. The town is home to the Ivy League university Dartmouth College, the U.S. Army Corps of En ...

, on February 11, 1978. His body was cremated and his ashes interred in the Thayer-Richards family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery. He was survived by his wife and sons. His papers are in the Harvard University Archives. Among them was a sealed brown Manila envelope that Conant had given the archives in 1951, with instructions that it was to be opened by the President of Harvard in the 21st century. Opened by Harvard's 28th president, Drew Faust, in 2007, it contained a letter in which Conant expressed his hopes and fears for the future. "You will... be in charge of a more prosperous and significant institution than the one over which I have the honor to preside", he wrote. "That arvardwill maintain the traditions of academic freedom, of tolerance for heresy, I feel sure."

Legacy

Conant is the namesake of James B. Conant High School in Hoffman Estates, Illinois, as well as James B. Conant Elementary School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.Graduate students

Former graduate students of Conant include: * Louis Fieser – organic chemist and professor emeritus at Harvard University renowned as the inventor of a militarily effective form of napalm. His award-winning research included work on blood-clotting agents including the first synthesis of vitamin K, synthesis and screening of quinones as antimalarial drugs, work with steroids leading to the synthesis of cortisone, and study of the nature of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. * Benjamin S. Garvey – noted chemist at BF Goodrich who worked on the development of synthetic rubber, contributed to understanding of vulcanization, and developed early techniques for small scale evaluation of rubbers. * Frank Westheimer – was the Morris Loeb Professor of Chemistry Emeritus at Harvard University.Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *:For a complete list of his published scientific papers, see .Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Wayne J. Urban, Scholarly Leadership in Higher Education: An Intellectual History of James Bryan Conant (Bloomsbury, 2021)External links

* * * *1965 Audio Interview with James B. Conant by Stephane Groueff

Voices of the Manhattan Project * Correspondence between Conant and Linus Pauling. {{DEFAULTSORT:Conant, James Bryant 1893 births 1978 deaths Conant family Ambassadors of the United States to Germany American physical chemists Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellows of the Royal Institute of Chemistry Foreign Members of the Royal Society Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Harvard College alumni Harvard University faculty Honorary Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Manhattan Project people Medal for Merit recipients Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People from Boston Presidents of Harvard University U.S. Synthetic Rubber Program Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients 20th-century American diplomats Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery 20th-century American academics