James Baird Weaver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

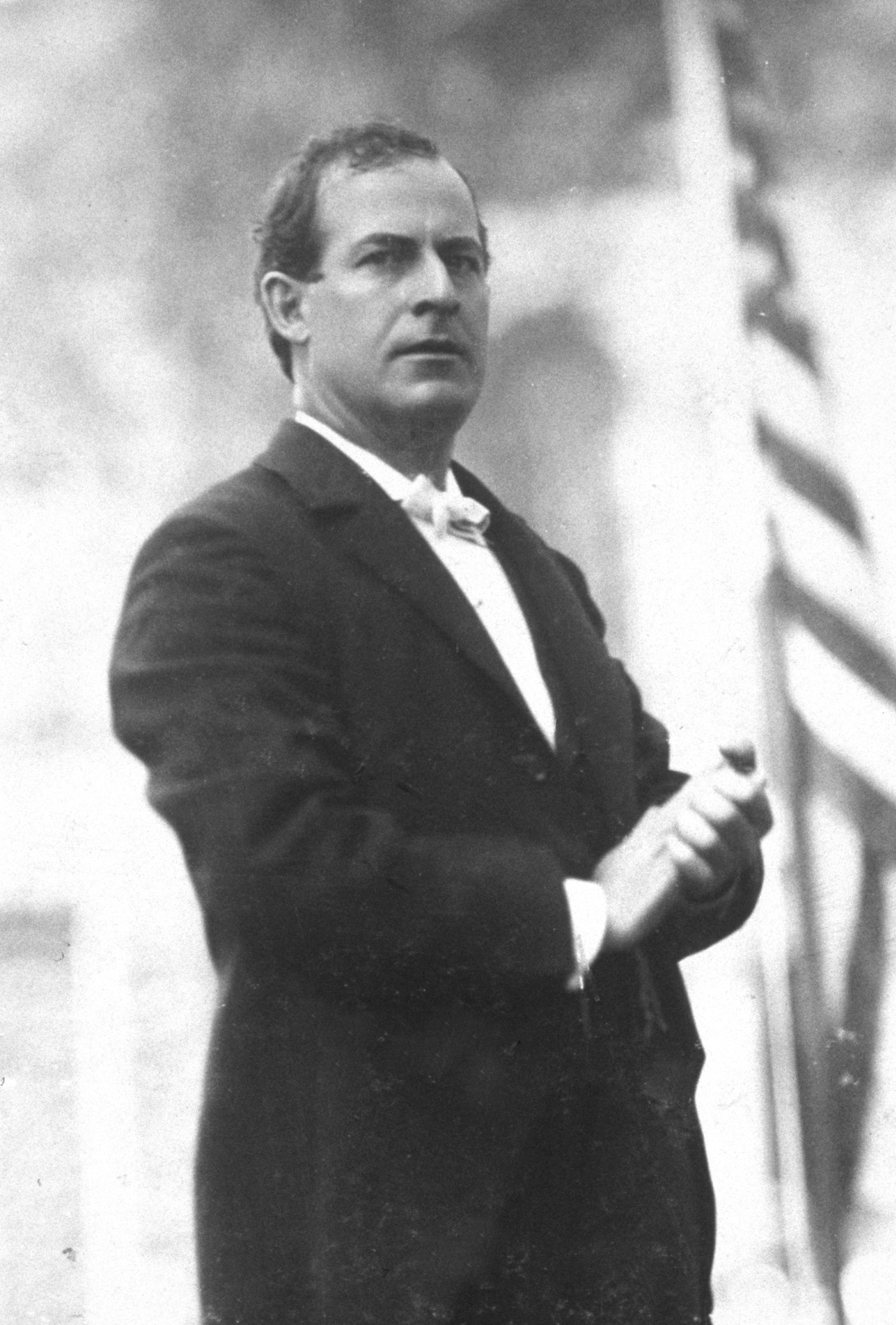

James Baird Weaver (June 12, 1833 – February 6, 1912) was a member of the

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 men to join the

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 men to join the

Soon after returning from the war, Weaver became editor of a pro-Republican Bloomfield newspaper, the ''Weekly Union Guard''. At the 1865 Iowa Republican State Convention, he placed second for the nomination for lieutenant governor. The following year, Weaver was elected district attorney for the second judicial district, covering six counties in southern Iowa. In 1867, President Andrew Johnson appointed him assessor of internal revenue in the first Congressional district, which extended across southeastern Iowa. The job came with a $1500 salary, plus a percentage of taxes collected over $100,000. Weaver held that lucrative position until 1872, when Congress abolished it. He also became involved in the

Soon after returning from the war, Weaver became editor of a pro-Republican Bloomfield newspaper, the ''Weekly Union Guard''. At the 1865 Iowa Republican State Convention, he placed second for the nomination for lieutenant governor. The following year, Weaver was elected district attorney for the second judicial district, covering six counties in southern Iowa. In 1867, President Andrew Johnson appointed him assessor of internal revenue in the first Congressional district, which extended across southeastern Iowa. The job came with a $1500 salary, plus a percentage of taxes collected over $100,000. Weaver held that lucrative position until 1872, when Congress abolished it. He also became involved in the

After his defeats in 1875, Weaver grew disenchanted with the Republican party, not only because it had spurned him, but also because of the policy choices of the dominant Allison faction. In May 1876, he traveled to Indianapolis to attend

After his defeats in 1875, Weaver grew disenchanted with the Republican party, not only because it had spurned him, but also because of the policy choices of the dominant Allison faction. In May 1876, he traveled to Indianapolis to attend

In May 1878, Weaver accepted the Greenback nomination for the House of Representatives in the 6th district. Although Weaver's political career up to then had been as a staunch Republican, Democrats in the 6th district thought that endorsing him was likely the only way to defeat Sampson, the incumbent Republican. Since the start of the Civil War, Democrats had been in the minority across Iowa; electoral fusion with Greenbackers represented their best chance to get their candidates into office. Hard-money Democrats objected to the idea, but some were reassured when Henry H. Trimble, a prominent Bloomfield Democrat, assured them that if elected Weaver would align with House Democrats on all issues other than the money question. Democrats declined to endorse any candidate at the 6th district convention, but soft-money leaders in the party circulated their own slate of candidates that included Democrats and Greenbackers. The Greenback–Democrat ticket prevailed, and Weaver was elected with 16,366 votes to Sampson's 14,307.

Weaver entered the 46th Congress in March 1879, one of thirteen Greenbackers elected in 1878. Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation. Weaver gave his first speech in April 1879, criticizing the use of the army to police Southern polling stations, while also decrying the violence against black Southerners that made such protection necessary; he then described the Greenback platform, which he said would put an end to the sectional and economic strife. The next month, he spoke in favor of a bill calling for an increase in the money supply by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver, but the bill was easily defeated. Weaver's oratorical skill drew praise, but he had no luck in advancing Greenback policy ideas.

In 1880, Weaver prepared a resolution stating that the government, not banks, should issue currency and determine its volume, and that the federal debt should be repaid in whatever currency the government chose, not just gold as the law then required. The proposed resolution would never be allowed to emerge from committees dominated by Democrats and Republicans, so Weaver planned to introduce it directly to the whole House for debate, as members were permitted to do every Monday. Rather than debate a proposition that would expose the monetary divide in the Democratic Party,

In May 1878, Weaver accepted the Greenback nomination for the House of Representatives in the 6th district. Although Weaver's political career up to then had been as a staunch Republican, Democrats in the 6th district thought that endorsing him was likely the only way to defeat Sampson, the incumbent Republican. Since the start of the Civil War, Democrats had been in the minority across Iowa; electoral fusion with Greenbackers represented their best chance to get their candidates into office. Hard-money Democrats objected to the idea, but some were reassured when Henry H. Trimble, a prominent Bloomfield Democrat, assured them that if elected Weaver would align with House Democrats on all issues other than the money question. Democrats declined to endorse any candidate at the 6th district convention, but soft-money leaders in the party circulated their own slate of candidates that included Democrats and Greenbackers. The Greenback–Democrat ticket prevailed, and Weaver was elected with 16,366 votes to Sampson's 14,307.

Weaver entered the 46th Congress in March 1879, one of thirteen Greenbackers elected in 1878. Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation. Weaver gave his first speech in April 1879, criticizing the use of the army to police Southern polling stations, while also decrying the violence against black Southerners that made such protection necessary; he then described the Greenback platform, which he said would put an end to the sectional and economic strife. The next month, he spoke in favor of a bill calling for an increase in the money supply by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver, but the bill was easily defeated. Weaver's oratorical skill drew praise, but he had no luck in advancing Greenback policy ideas.

In 1880, Weaver prepared a resolution stating that the government, not banks, should issue currency and determine its volume, and that the federal debt should be repaid in whatever currency the government chose, not just gold as the law then required. The proposed resolution would never be allowed to emerge from committees dominated by Democrats and Republicans, so Weaver planned to introduce it directly to the whole House for debate, as members were permitted to do every Monday. Rather than debate a proposition that would expose the monetary divide in the Democratic Party,

By 1879, the Greenback coalition had divided, with the faction most prominent in the South and West, led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy, splitting from the main party. Pomeroy's faction, called the "Union Greenback Labor Party", was more radical and emphasized its independence, and suggested that Eastern Greenbackers were likely to "sell out the party at any time to the Democrats". Weaver remained with the rump Greenback party, often called the "National Greenback Party", and the national reputation he had earned in Congress made him one of the party's leading presidential hopefuls.

The Union Greenbackers held their convention first and nominated Stephen D. Dillaye of New Jersey for president and Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas for vice president, but also sent a delegation to the National Greenback convention in Chicago that June, with an eye toward reuniting the party. The two factions agreed to reunify, and also to admit a delegation from the

By 1879, the Greenback coalition had divided, with the faction most prominent in the South and West, led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy, splitting from the main party. Pomeroy's faction, called the "Union Greenback Labor Party", was more radical and emphasized its independence, and suggested that Eastern Greenbackers were likely to "sell out the party at any time to the Democrats". Weaver remained with the rump Greenback party, often called the "National Greenback Party", and the national reputation he had earned in Congress made him one of the party's leading presidential hopefuls.

The Union Greenbackers held their convention first and nominated Stephen D. Dillaye of New Jersey for president and Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas for vice president, but also sent a delegation to the National Greenback convention in Chicago that June, with an eye toward reuniting the party. The two factions agreed to reunify, and also to admit a delegation from the

Weaver also took up the issue of white settlement in

Weaver also took up the issue of white settlement in

The new president, Republican

The new president, Republican

The following year, Weaver accepted the decision to form a new party (called the People's Party or Populist Party) and published a book, ''A Call to Action'', detailing the party's principles and castigating the "few haughty millionaires who are gathering up the riches of the new world". He attended their convention in

The following year, Weaver accepted the decision to form a new party (called the People's Party or Populist Party) and published a book, ''A Call to Action'', detailing the party's principles and castigating the "few haughty millionaires who are gathering up the riches of the new world". He attended their convention in

The next year, 1894, saw pay cuts and labor disturbances, including a massive strike by the workers at the Pullman Company. A group of unemployed workers, known as

The next year, 1894, saw pay cuts and labor disturbances, including a massive strike by the workers at the Pullman Company. A group of unemployed workers, known as

The Republican Party's popularity after the victory in the

The Republican Party's popularity after the victory in the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

and two-time candidate for President of the United States. Born in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, he moved to Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

as a boy when his family claimed a homestead on the frontier. He became politically active as a young man and was an advocate for farmers and laborers. He joined and quit several political parties in the furtherance of the progressive causes in which he believed. After serving in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Weaver returned to Iowa and worked for the election of Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

candidates. After several unsuccessful attempts at Republican nominations to various offices, and growing dissatisfied with the conservative wing of the party, in 1877 Weaver switched to the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

, which supported increasing the money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circul ...

and regulating big business

Big business involves large-scale corporate-controlled financial or business activities. As a term, it describes activities that run from "huge transactions" to the more general "doing big things". In corporate jargon, the concept is commonly ...

. As a Greenbacker with Democratic support, Weaver won election to the House in 1878.

The Greenbackers nominated Weaver for president in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

, but he received only 3.3 percent of the popular vote. After several more attempts at elected office, he was again elected to the House in 1884 and 1886. In Congress, he worked for expansion of the money supply and for the opening of Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

to white settlement. As the Greenback Party fell apart, a new anti-big business third party, the People's Party ("Populists"), arose. Weaver helped to organize the party and was their nominee for president in 1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

. This time he was more successful and gained 8.5 percent of the popular vote and won five states, but still fell far short of victory. The Populists merged with the Democrats by the end of the 19th century, and Weaver went with them, promoting the candidacy of William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

for president in 1896

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end, as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports that ...

, 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

, and 1908. After serving as mayor of his home town, Colfax, Iowa

Colfax is a city in Jasper County, Iowa, United States. Colfax is located approximately 24 miles east of Des Moines. The town was founded in 1866, and was named after Schuyler Colfax, vice president under Ulysses S. Grant. The population was 2,255 ...

, Weaver retired from his pursuit of elective office. He died in Iowa in 1912. Most of Weaver's political goals remained unfulfilled at his death, but many came to pass in the following decades.

Early years

James Baird Weaver was born inDayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater D ...

, on June 12, 1833, the fifth of thirteen children of Abram Weaver and Susan Imlay Weaver. Weaver's father was a farmer, also born in Ohio, and a descendant of Revolutionary War veterans. He married Weaver's mother, who was from New Jersey, in 1824. Shortly after Weaver's birth, in 1835, the family moved to a farm nine miles north of Cassopolis, Michigan. In 1842, the family moved again to the Iowa Territory

The Territory of Iowa was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1838, until December 28, 1846, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Iowa. The remain ...

to await the opening of former Sac and Fox

The Sac and Fox Nation ( ''Mesquakie'' language: ''Othâkîwaki / Thakiwaki'' or ''Sa ki wa ki'') is the largest of three federally recognized tribes of Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) Indian peoples. Originally from the Lake Huron and Lake Michigan ...

land to white settlement the following year. They claimed a homestead along the Chequest Creek in Davis County. Abram Weaver built a house and farmed his new land until 1848, when the family moved to Bloomfield, the county seat.

Abram Weaver, a Democrat involved in local politics, was elected clerk of the district court in 1848; he often vied for election to other offices, usually unsuccessfully. Weaver's brother-in-law, Hosea Horn, a Whig, was appointed postmaster the following year, and through him James Weaver secured his first job, delivering mail to neighboring Jefferson County. In 1851, Weaver quit the mail route to read law with Samuel G. McAchran, a local lawyer. Two years later, Weaver interrupted his legal career to accompany another brother-in-law, Dr. Calvin Phelps, on a cattle drive overland from Bloomfield to Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

. Weaver initially intended to stay and prospect for gold, but instead booked passage on a ship for Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

. He crossed the isthmus, boarded another ship to New York, and returned home to Iowa.

Upon his return, Weaver worked briefly as a store clerk before resuming the study of law. He enrolled at the Cincinnati Law School

The University of Cincinnati College of Law was founded in 1833 as the Cincinnati Law School. It is the fourth oldest continuously running law school in the United States — after Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Yale — and the first in ...

in 1855, where he studied under Bellamy Storer. While in Cincinnati, Weaver began to question his support for the institution of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, a change biographers attribute to Storer's influence. After graduating in 1856, Weaver returned to Bloomfield and was admitted to the Iowa bar. By 1857, he broke with the Democratic party of his father to join the growing coalition that opposed the expansion of slavery, which became the Republican Party.

Weaver traveled around southern Iowa in 1858, giving speeches on behalf of his new party's candidates. That summer, he married Clarrisa (Clara) Vinson, a schoolteacher from nearby Keosauqua, Iowa

Keosauqua ( ) is a city in Van Buren County, Iowa, United States. The population was 936 at the time of the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Van Buren County.

History

Keosauqua was laid out in 1839. The word Keosauqua derives from the Me ...

, whom he had courted since he returned from Cincinnati. The marriage lasted until Weaver's death in 1912 and the couple had eight children. After the wedding, Weaver started a law firm with Hosea Horn and continued his involvement in Republican politics. He gave several speeches on behalf of Samuel J. Kirkwood for governor in 1859 in a campaign that focused heavily on the slavery debate; although the Republicans lost Weaver's Davis County, Kirkwood narrowly won the election. The next year, Weaver served as a delegate to the state convention and, although not a national delegate, traveled with the Iowa delegation to the 1860 Republican National Convention, where Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

was nominated. Lincoln carried Iowa and won the election, but Southern states responded to the Republican victory by seceding from the Union. By April 1861, the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

had begun.

Civil War

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 men to join the

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 men to join the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

. Weaver enlisted in what became Company G of the 2nd Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and was elected the company's first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

. The 2nd Iowa, commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Samuel Ryan Curtis

Samuel Ryan Curtis (February 3, 1805 – December 26, 1866) was an American military officer and one of the first Republicans elected to Congress. He was most famous for his role as a Union Army general in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the ...

, a former Congressman, was ordered to Missouri in June 1861 to secure railroad lines in that border state. Weaver's unit spent that summer in northern Missouri and did not see action. In the meantime, Clara gave birth to the couple's second child and first son, named James Bellamy Weaver after his father and Bellamy Storer.

Weaver's first chance at action came in February 1862, when the 2nd Iowa joined Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Ulysses S. Grant's army outside the Confederate Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

in Tennessee. Weaver's company was in the thick of the fight, which he described as a "holocaust to the demon of battles", and he took a minor wound in the arm. The rebels surrendered the next day, the most important Union victory of the war to date. The 2nd Iowa next joined other units in the area at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee

Pittsburg Landing is a river landing on the west bank of the Tennessee River in Hardin County, Tennessee. It was named for "Pitts" Tucker who operated a tavern at the site in the years preceding the Civil War. It is located at latitude 35.15222 ...

, to mass for a major assault deeper into the South. Confederate forces met them there, in the Battle of Shiloh. Weaver's regiment was in the center of the Union lines, in the area later known as the "hornets' nest", and were forced to retreat amid fierce fighting. The next day, the Union forces turned the tide and forced the rebels off the field in what Weaver called a "perfect rout". The carnage at Shiloh—20,000 killed and wounded—was on a scale never before seen in American warfare, and both sides learned that the war would end neither quickly nor easily.

After Shiloh, Weaver and the 2nd Iowa slowly advanced to Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,573 at the 2010 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

History

Corinth was founded i ...

, where he was promoted to major. Rebel forces attacked the Union armies there in the Second Battle of Corinth

The second Battle of Corinth (which, in the context of the American Civil War, is usually referred to as the Battle of Corinth, to differentiate it from the siege of Corinth earlier the same year) was fought October 3–4, 1862, in Corinth, ...

, where Weaver's courage in that Union victory convinced his superiors to promote him to colonel after the regiment's commanding officer was killed. After Corinth, Weaver's unit took up garrison duty in northern Mississippi. In the summer of 1863, they were redeployed to the Tennessee–Alabama border, again on occupation duty around Pulaski, Tennessee

Pulaski is a city in and the county seat of Giles County, which is located on the central-southern border of Tennessee, United States. The population was 8,397 at the 2020 census. It was named after Casimir Pulaski, a noted Polish-born soldier ...

. They rejoined the action at the Battle of Resaca

The Battle of Resaca, from May 13 to 15, 1864, formed part of the Atlanta Campaign during the American Civil War, when a Union force under William Tecumseh Sherman engaged the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by Joseph E. Johnston. The battle ...

, a part of the Atlanta Campaign, then continued with Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's march through Georgia to the sea in 1864. Weaver's enlistment ended in May 1864, and he returned to his family in Iowa. After the war ended, Weaver received a promotion to brevet brigadier general, backdated to March 13, 1865.

Republican politics

Soon after returning from the war, Weaver became editor of a pro-Republican Bloomfield newspaper, the ''Weekly Union Guard''. At the 1865 Iowa Republican State Convention, he placed second for the nomination for lieutenant governor. The following year, Weaver was elected district attorney for the second judicial district, covering six counties in southern Iowa. In 1867, President Andrew Johnson appointed him assessor of internal revenue in the first Congressional district, which extended across southeastern Iowa. The job came with a $1500 salary, plus a percentage of taxes collected over $100,000. Weaver held that lucrative position until 1872, when Congress abolished it. He also became involved in the

Soon after returning from the war, Weaver became editor of a pro-Republican Bloomfield newspaper, the ''Weekly Union Guard''. At the 1865 Iowa Republican State Convention, he placed second for the nomination for lieutenant governor. The following year, Weaver was elected district attorney for the second judicial district, covering six counties in southern Iowa. In 1867, President Andrew Johnson appointed him assessor of internal revenue in the first Congressional district, which extended across southeastern Iowa. The job came with a $1500 salary, plus a percentage of taxes collected over $100,000. Weaver held that lucrative position until 1872, when Congress abolished it. He also became involved in the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

, serving as a delegate to a church convention in Baltimore in 1876. Membership in the Methodist church coincided with Weaver's interest in the growing movement for prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages. His income and prestige grew along with his family, which included seven children by 1877. Weaver's success allowed him to build a large new home for his family, which still stands.

Weaver's work for the party led many to support his nomination to represent Iowa's 6th congressional district in the federal House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in 1874. Many party insiders, however, were wary of Weaver's association with the Prohibition movement and preferred to remain uncommitted on the divisive issue. At the convention, Weaver led on the first ballot, but ultimately lost the nomination by one vote to Ezekiel S. Sampson, a local judge. Weaver's allies attributed his loss to "the meanest kind of wire pulling", but Weaver shrugged off the defeat and aimed instead at the gubernatorial nomination in 1875. He launched a vigorous effort, courted delegates around the state, and explicitly endorsed Prohibition and greater state control of railroad rates. Weaver attracted many delegates' support, but alienated those who were friendly to the railroads and wished to avoid the liquor issue. Opposition was scattered among several lesser-known candidates, mostly members of Senator William B. Allison's conservative wing of the party. They united at the convention when a delegate unexpectedly nominated former governor Kirkwood. The nomination carried easily and, after Allison's associates persuaded him to accept it, Kirkwood was nominated, and went on to win the election. In a further defeat, the delegates refused to endorse Prohibition in the party platform. Weaver had small consolation in a nomination to the state Senate, but he lost to his Democratic opponent in the election that fall.

Switch to the Greenback Party

After his defeats in 1875, Weaver grew disenchanted with the Republican party, not only because it had spurned him, but also because of the policy choices of the dominant Allison faction. In May 1876, he traveled to Indianapolis to attend

After his defeats in 1875, Weaver grew disenchanted with the Republican party, not only because it had spurned him, but also because of the policy choices of the dominant Allison faction. In May 1876, he traveled to Indianapolis to attend the national convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

of the newly formed Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

. The new party had arisen, mostly in the West, as a response to the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

. During the Civil War, Congress had authorized " greenbacks", a new form of fiat money

Fiat money (from la, fiat, "let it be done") is a type of currency that is not backed by any commodity such as gold or silver. It is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender. Throughout history, fiat money was sometim ...

that was redeemable not in gold but in government bonds. The greenbacks had helped to finance the war when the government's gold supply did not keep pace with the expanding costs of maintaining the armies. When the crisis had passed, many in both parties, especially in the East, wanted to place the nation's currency on a gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

as soon as possible. The Specie Payment Resumption Act The Specie Payment Resumption Act of January 14, 1875 was a law in the United States that restored the nation to the gold standard through the redemption of previously-unbacked United States Notes and reversed inflationary government policies promot ...

, passed in 1875, ordered that greenbacks be gradually withdrawn and replaced with gold-backed currency beginning in 1879. At the same time, the depression had made it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less valuable. Beyond their support for a larger money supply, Greenbackers also favored an eight-hour work day, safety regulations in factories, and an end to child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

. As historian Herbert Clancy put it, they "anticipated by almost fifty years the progressive legislation of the first quarter of the twentieth century".

In the 1876 presidential campaign, the Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes and the Democrats chose Samuel J. Tilden. Both candidates opposed the issuance of more greenbacks (candidates who favored the gold-backed currency were called "hard money" supporters, while the Greenbackers' policy of encouraging inflation was known as "soft money".) Weaver was impressed with the Greenbackers and their candidate, Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the '' Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of ...

, but while he advocated some soft-money policies, he declined the Greenback nomination for Congress and remained a Republican; he campaigned for Hayes in the election that year. In 1877, Weaver attended the Republican state convention and saw the state party adopt a soft-money platform that also favored Prohibition. The gubernatorial nominee, however, was John H. Gear, an opponent of Prohibition who had worked to defeat Weaver in his quest for the governorship two years earlier. After initially supporting Gear, Weaver joined the Greenback party in August. He gave speeches on behalf of his new party, debated former allies across the state, and establishing himself as a prominent advocate for the Greenback cause.

Congress

In May 1878, Weaver accepted the Greenback nomination for the House of Representatives in the 6th district. Although Weaver's political career up to then had been as a staunch Republican, Democrats in the 6th district thought that endorsing him was likely the only way to defeat Sampson, the incumbent Republican. Since the start of the Civil War, Democrats had been in the minority across Iowa; electoral fusion with Greenbackers represented their best chance to get their candidates into office. Hard-money Democrats objected to the idea, but some were reassured when Henry H. Trimble, a prominent Bloomfield Democrat, assured them that if elected Weaver would align with House Democrats on all issues other than the money question. Democrats declined to endorse any candidate at the 6th district convention, but soft-money leaders in the party circulated their own slate of candidates that included Democrats and Greenbackers. The Greenback–Democrat ticket prevailed, and Weaver was elected with 16,366 votes to Sampson's 14,307.

Weaver entered the 46th Congress in March 1879, one of thirteen Greenbackers elected in 1878. Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation. Weaver gave his first speech in April 1879, criticizing the use of the army to police Southern polling stations, while also decrying the violence against black Southerners that made such protection necessary; he then described the Greenback platform, which he said would put an end to the sectional and economic strife. The next month, he spoke in favor of a bill calling for an increase in the money supply by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver, but the bill was easily defeated. Weaver's oratorical skill drew praise, but he had no luck in advancing Greenback policy ideas.

In 1880, Weaver prepared a resolution stating that the government, not banks, should issue currency and determine its volume, and that the federal debt should be repaid in whatever currency the government chose, not just gold as the law then required. The proposed resolution would never be allowed to emerge from committees dominated by Democrats and Republicans, so Weaver planned to introduce it directly to the whole House for debate, as members were permitted to do every Monday. Rather than debate a proposition that would expose the monetary divide in the Democratic Party,

In May 1878, Weaver accepted the Greenback nomination for the House of Representatives in the 6th district. Although Weaver's political career up to then had been as a staunch Republican, Democrats in the 6th district thought that endorsing him was likely the only way to defeat Sampson, the incumbent Republican. Since the start of the Civil War, Democrats had been in the minority across Iowa; electoral fusion with Greenbackers represented their best chance to get their candidates into office. Hard-money Democrats objected to the idea, but some were reassured when Henry H. Trimble, a prominent Bloomfield Democrat, assured them that if elected Weaver would align with House Democrats on all issues other than the money question. Democrats declined to endorse any candidate at the 6th district convention, but soft-money leaders in the party circulated their own slate of candidates that included Democrats and Greenbackers. The Greenback–Democrat ticket prevailed, and Weaver was elected with 16,366 votes to Sampson's 14,307.

Weaver entered the 46th Congress in March 1879, one of thirteen Greenbackers elected in 1878. Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation. Weaver gave his first speech in April 1879, criticizing the use of the army to police Southern polling stations, while also decrying the violence against black Southerners that made such protection necessary; he then described the Greenback platform, which he said would put an end to the sectional and economic strife. The next month, he spoke in favor of a bill calling for an increase in the money supply by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver, but the bill was easily defeated. Weaver's oratorical skill drew praise, but he had no luck in advancing Greenback policy ideas.

In 1880, Weaver prepared a resolution stating that the government, not banks, should issue currency and determine its volume, and that the federal debt should be repaid in whatever currency the government chose, not just gold as the law then required. The proposed resolution would never be allowed to emerge from committees dominated by Democrats and Republicans, so Weaver planned to introduce it directly to the whole House for debate, as members were permitted to do every Monday. Rather than debate a proposition that would expose the monetary divide in the Democratic Party, Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

Samuel J. Randall refused to recognize Weaver when he rose to propose the resolution. Weaver returned to the floor each succeeding Monday, with the same result, and the press took notice of Randall's obstruction. Eventually, Republican James A. Garfield of Ohio interceded with Randall to recognize Weaver, which he reluctantly did on April 5, 1880. The Republicans, mostly united behind hard money, largely voted against the measure, while many Democrats joined the Greenbackers voting in favor. Despite support by the soft-money Democrats, the resolution was defeated 84–117 with many members abstaining. Although he lost the vote, Weaver had promoted the monetary issue in the national consciousness.

Presidential election of 1880

By 1879, the Greenback coalition had divided, with the faction most prominent in the South and West, led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy, splitting from the main party. Pomeroy's faction, called the "Union Greenback Labor Party", was more radical and emphasized its independence, and suggested that Eastern Greenbackers were likely to "sell out the party at any time to the Democrats". Weaver remained with the rump Greenback party, often called the "National Greenback Party", and the national reputation he had earned in Congress made him one of the party's leading presidential hopefuls.

The Union Greenbackers held their convention first and nominated Stephen D. Dillaye of New Jersey for president and Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas for vice president, but also sent a delegation to the National Greenback convention in Chicago that June, with an eye toward reuniting the party. The two factions agreed to reunify, and also to admit a delegation from the

By 1879, the Greenback coalition had divided, with the faction most prominent in the South and West, led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy, splitting from the main party. Pomeroy's faction, called the "Union Greenback Labor Party", was more radical and emphasized its independence, and suggested that Eastern Greenbackers were likely to "sell out the party at any time to the Democrats". Weaver remained with the rump Greenback party, often called the "National Greenback Party", and the national reputation he had earned in Congress made him one of the party's leading presidential hopefuls.

The Union Greenbackers held their convention first and nominated Stephen D. Dillaye of New Jersey for president and Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas for vice president, but also sent a delegation to the National Greenback convention in Chicago that June, with an eye toward reuniting the party. The two factions agreed to reunify, and also to admit a delegation from the Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

. Thus united, the convention turned to nominations. Weaver led on the first ballot, and on the second he secured a majority. Chambers won the convention's vote for vice president.

In a departure from the political traditions of the day, Weaver himself campaigned, making speeches across the South in July and August. As the Greenbackers had the only ticket that included a Southerner, Weaver and Chambers hoped to make inroads in the South. As the campaign progressed, however, Weaver's message of racial inclusion drew violent protests in the South, as the Greenbackers faced the same obstacles the Republicans did in the face of increasing black disenfranchisement. In the autumn, Weaver campaigned in the North, but the Greenbackers' lack of support was compounded by Weaver's refusal to run a fusion ticket in states where Democratic and Greenbacker strength might have combined to outvote the Republicans.

Weaver received 305,997 votes and no electoral votes, compared to 4,446,158 for the winner, Republican James A. Garfield, and 4,444,260 for Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

. The party was strongest in the West and South, but in no state did Weaver receive more than 12 percent of the vote (his best state was Texas, with 11.7 percent); his nationwide total was just 3 percent. That figure represented an improvement over the Greenback vote of 1876, but to Weaver, who expected twice as many votes as he received, it was a disappointment.

Office-seeker and party promoter

After the election, Weaver returned to the lame-duck session of Congress and proposed an unsuccessful constitutional amendment that would have provided for the direct election of Senators. After his term expired in March, he resumed his speaking tour, promoting the Greenback Party across the nation. He and Edward H. Gillette, another Iowa Greenback Congressman, bought the ''Iowa Tribune'' in 1882 to help spread the Greenback message. That same year, Weaver ran for his old 6th district seat in the House against the incumbent Republican, Marsena E. Cutts. This time the Democrats and Greenbackers ran separate candidates, and Weaver finished a distant second. Cutts died before taking office, and the Republicans offered to let Weaver run unopposed in the special election if he rejoined their party; he declined, and John C. Cook, a Democrat, won the seat. In 1883, Weaver was the Greenback nominee for governor of Iowa. Again, the Democrats ran a separate candidate and the incumbent Republican, Buren R. Sherman, was re-elected with a plurality. Weaver was a delegate to the 1884 Greenback National Convention in Indianapolis and supported the eventual nominee,Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

of Massachusetts. Back in Iowa, Weaver again ran for the House, this time with the Democrats' support. Greenback fortunes declined nationally, as Butler received just over half as many votes for president as Weaver had four years earlier. Weaver's House race bucked the trend: he defeated Republican Frank T. Campbell by just 67 votes.

Return to Congress

Unlike in his previous congressional term, when Weaver entered the 49th United States Congress, he was the only Greenback member. The new president, DemocratGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, was friendly to Weaver, and asked his advice on Iowa patronage. As it had been for years, Weaver's chief concern was with the nation's money and finance, and the relationship between labor and capital.

In 1885, he proposed the creation of a Department of Labor

The Ministry of Labour ('' UK''), or Labor ('' US''), also known as the Department of Labour, or Labor, is a government department responsible for setting labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, training, a ...

, which he suggested would find a solution to disputes between labor and management. Labor tensions increased the following year as the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

went on strike against Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

's rail empire, and a strike against the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company

The International Harvester Company (often abbreviated by IHC, IH, or simply International ( colloq.)) was an American manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment, automobiles, commercial trucks, lawn and garden products, household e ...

ended in the bloody Haymarket riot

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in ...

. Weaver believed the nation's hard-money policies were responsible for labor unrest, calling it "purely a question of money, and nothing else" and declaring, "If this Congress will not protect labor, it must protect itself". He saw the triumph of one plank of the Greenback platform when Congress established the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate the railroads. Weaver thought the bill should have given the government more power, including the ability to set rates directly, but he voted for the final bill.

Weaver also took up the issue of white settlement in

Weaver also took up the issue of white settlement in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

. For several years, white settlers had been claiming homesteads in the Unassigned Lands

The Unassigned Lands in Oklahoma were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek (Muskogee) and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled. By 1883 it was bounded by the Cher ...

in what is now Oklahoma. After the Civil War, the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

had been forced to cede their unused western lands to the federal government. The settlers, known as Boomers, believed that federal ownership made the lands open to settlement under the Homestead Acts

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

. The federal government disagreed, as did the Cherokee Nation, which leased its neighboring Cherokee Outlet

The Cherokee Outlet, or Cherokee Strip, was located in what is now the state of Oklahoma in the United States. It was a 60-mile-wide (97 km) parcel of land south of the Oklahoma-Kansas border between 96 and 100°W. The Cherokee Outlet wa ...

to Kansas cattle ranchers, and many Easterners, who believed the Boomers to be the tools of railroad interests. Weaver saw the issue as one between the landless poor homesteaders and wealthy cattlemen, and took the side of the former. He introduced a bill in December 1885 to organize Indian Territory and the neighboring Neutral Strip into a new Oklahoma Territory. The bill died in committee, but Weaver reintroduced it in February 1886 and gave a speech calling for the Indian reservations to be broken up into homesteads for individual Natives and the remaining land to be open to white settlement.

The Committee on Territories again rejected Weaver's bill, but approved a compromise measure that opened the Unassigned Lands, Cherokee Outlet, and Neutral Strip to settlement. Congress debated the bill over several months, while the tribes announced their resistance to their lands becoming a territory; according to an 1884 Supreme Court decision, '' Elk v. Wilkins'', Native Americans were not citizens, and thus would have no voting rights in the new territory. When Weaver returned to Iowa to campaign for re-election, the bill was still in limbo. Running again on a Democratic–Greenback fusion ticket, Weaver was re-elected to the House in 1886 with a 618-vote majority.

In the lame-duck session of 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pres ...

, which allowed the president to terminate tribal governments, and broke up Indian reservations into homesteads for individual natives. Although the Five Civilized Tribes were exempt from the Act, the spirit of the law encouraged Weaver and the Boomers to continue their own efforts to open western Indian Territory to white settlement. Weaver reintroduced his Oklahoma bill in the new Congress the following year, but again it stalled in committee. He returned to Iowa for another re-election campaign in September 1888, but the Greenback party had fallen apart, replaced by a new left-wing third party, the Union Labor Party. In Iowa's 6th district, the new party agreed to fuse with Democrats to nominate Weaver, but this time the Republicans were stronger. Their candidate, John F. Lacey, was elected with an 828-vote margin. The Union Laborites and their presidential candidate, Alson Streeter

Alson Jenness Streeter (January 18, 1823 – November 24, 1901) was an American farmer, miner and politician who was the Union Labor Party nominee in the United States presidential election of 1888. He was also an early member of the National Gra ...

, fared poorly nationally as well, and the new party soon dissolved. Weaver returned to Congress for the lame-duck session and once more pushed to organize the Oklahoma Territory. This time he prevailed, as the House voted 147–102 to open the Unassigned Lands to homesteaders. The Senate followed suit and President Cleveland, who was about to leave office, signed the bill into law.

Farmers' Alliance and a new party

The new president, Republican

The new president, Republican Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, set April 22, 1889, as the date when the rush for the Unassigned Lands would begin. Weaver arrived at a railroad station in the territory in March with an eye toward relocating there. The would-be homesteaders welcomed him with great acclaim. Although settlers were not allowed to stake claims before noon on April 22, many scouted out the land ahead of time, and even marked off informal claims; Weaver was among them. After the rush, settlers who had waited challenged the claims of the " Sooners" who had entered early. Weaver's identification with the group harmed his popularity in the territory. His claim was ultimately denied, and he returned to Iowa in 1890.

Weaver and his wife moved their household in 1890 from Bloomfield to Colfax, near Des Moines, as the former Congressman took up more active management of the ''Iowa Tribune''. The Greenback and Union Labor parties were defunct, but he still proselytized for their ideals. In August 1890, Weaver addressed a convention in Des Moines where former Greenbackers and Laborites gathered, although he declined their nomination for Congress. The economic conditions that had created the Greenback party had not gone away; many farmers and laborers believed their situation had gotten worse since the Long Depression began in 1873. Many farmers had joined the Farmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

, which sought to promote soft-money ideas on a non-partisan basis; rather than create a third party, they endorsed major party candidates who supported their ideas and hired speakers to educate the public. Alliance-backed candidates did well in the 1890 elections, especially in the South, where Democrats endorsed by the Alliance won 44 seats.

Alliance members gathered that December in Ocala, Florida, and formulated a platform, later called the Ocala Demands

The Ocala Demands was a platform for economic and political reform that was later adopted by the People's Party.

In December, 1890, the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, more commonly known as the Southern Farmers' Alliance, its a ...

, that called for looser money, government control of the railroads, a graduated income tax, and the direct election of senators. Weaver endorsed the message in the ''Tribune'' and corresponded with the group's leader, Leonidas L. Polk. Weaver attended the group's convention in Cincinnati in May 1891, where he and Polk argued against forming a third party. Another delegate, Ignatius L. Donnelly, argued forcefully for a break from the two major parties, and his argument carried the day, although Weaver and Polk kept many of Donnelly's more radical proposals out of the convention's statement of principles.

Presidential election of 1892

The following year, Weaver accepted the decision to form a new party (called the People's Party or Populist Party) and published a book, ''A Call to Action'', detailing the party's principles and castigating the "few haughty millionaires who are gathering up the riches of the new world". He attended their convention in

The following year, Weaver accepted the decision to form a new party (called the People's Party or Populist Party) and published a book, ''A Call to Action'', detailing the party's principles and castigating the "few haughty millionaires who are gathering up the riches of the new world". He attended their convention in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

, in July 1892. After Polk's sudden death in June, Weaver was considered the front-runner for the nomination. He was nominated on the first ballot, easily besting his closest rival, Senator James H. Kyle of South Dakota. Weaver accepted the nomination and promised to "visit every state in the Union and carry the banner of the people into the enemy's camp". The vice presidential nomination went to James G. Field, a Confederate veteran and former Attorney General of Virginia

The attorney general of Virginia is an elected constitutional position that holds an executive office in the government of Virginia. Attorneys general are elected for a four-year term in the year following a presidential election. There are no ...

.

The platform adopted in Omaha was ambitious for its time, calling for a graduated income tax, public ownership of the railroads, telegraph, and telephone systems, government-issued currency, and the unlimited coinage of silver (the idea that the United States would buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins) at a favorable 16-to-1 ratio with gold. The Republicans nominated Harrison for re-election, and the Democrats put forward ex-President Cleveland; as in 1880, Weaver was confident of a good showing for the new party against their opponents. Harrison had shown some favor to the free silver cause, but his party largely supported the hard-money gold standard; Cleveland was solidly for gold, but his running mate, Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, was a silverite. Against these, the Populist Party stood alone as undisputed partisans of soft money, which Weaver hoped would lead to success in rural areas. Further, as labor disturbances broke out in Homestead, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere, Weaver hoped urban laborers would rally to the Populist cause.

Weaver embarked on a speaking tour across the northern plains and Pacific coast states. In late August, he turned South, hoping to break the Democrats' grip on those states. As in 1880, the issue of race hurt Weaver among white Southern voters, as he sought to attract black voters by urging cooperation between white and black farmers and calling for an end to lynchings. Weaver drew good crowds in the South, but he and his wife were also subjected to abuse from hecklers. Southern Democrats depicted Weaver as a threat to the conservative Democrats in power there; with the increasing disenfranchisement of black voters, this was to prove fatal to the Populists' hopes in the South.

On election day, Cleveland triumphed, carrying the entire South and many Northern states. Weaver's performance was better than that of any third party candidate since the Civil War, as he won over a million votes—8.5 percent of the total cast nationwide. In four states, he won a plurality, giving the Populists the electoral votes of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

, and Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

along with two more votes from North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

and Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

: twenty-two in total. Weaver believed the performance "a surprising success", and thought it portended good results in future elections. "Unaided by money," he said afterward, "our grand young party has made an enviable record and achieved a surprising success at the polls."

Populist elder statesman

Weaver believed that the Populists' embrace of free silver would be the main issue to attract new members to the party. After the election, he attended a meeting of theAmerican Bimetallic League

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, a pro-silver group, and gave speeches advocating an inflationist monetary policy. In the meantime, the Panic of 1893 caused bank failures, factory closures, and general economic upheaval. As the federal gold reserves dwindled, President Cleveland convinced Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which ensured the government would purchase less silver for coining and which further disconcerted free silver supporters. While depletion of gold reserves slowed after the repeal, the country's economy still floundered.

The next year, 1894, saw pay cuts and labor disturbances, including a massive strike by the workers at the Pullman Company. A group of unemployed workers, known as

The next year, 1894, saw pay cuts and labor disturbances, including a massive strike by the workers at the Pullman Company. A group of unemployed workers, known as Coxey's Army

Coxey's Army was a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey. They marched on Washington, D.C. in 1894, the second year of a four-year economic depression that was the worst in United Sta ...

, marched on Washington that spring. Weaver met with them in Iowa and expressed sympathy with the movement, so long as they refrained from lawbreaking. He then returned to the campaign trail, stumping for Populist candidates in the 1894 midterm elections. The election proved disastrous for the Democrats, but most of the gains went to the Republicans rather than to the Populists, who gained a few seats in the South but lost ground in the West. During the election, Weaver became friendly with William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, a Democratic Congressman from Nebraska and a charismatic supporter of free silver. Bryan had lost his bid for the Senate in the election, but his reputation as an exciting speaker made him a presidential possibility in 1896.

Weaver privately supported Bryan's quest for the Democratic nomination in 1896, which their convention awarded him on the fifth ballot. When the Populist convention gathered the next month in Chicago, they divided between endorsing the silverite Democrat and preserving their new party's independence. Weaver backed the former course, holding the issues the party stood for to be of more importance than the party itself. A majority of delegates agreed, but without the enthusiasm that had marked their convention of four years earlier. At the same time, Weaver joined with anti-fusionists to keep the Populist platform from deviating from the party's ideological principles. Against the fusion candidate stood Republican William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

of Ohio, a hard-money conservative. Bryan succeeded in uniting the South and West, Weaver's longtime dream, but with the more populous North solidly behind McKinley, Bryan lost the election.

Despite the loss, Weaver still believed the Populist cause would triumph. He agreed to be nominated one last time for his old 6th district House seat on a Democratic-Populist fusion ticket. As he had ten years earlier, Republican John Lacey defeated Weaver. In 1900, Weaver attended a convention of fusionist Populists in Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Sioux Falls () is the most populous city in the U.S. state of South Dakota and the 130th-most populous city in the United States. It is the county seat of Minnehaha County and also extends into Lincoln County to the south, which continues up ...

, the party having split on the issue of cooperation with the Democrats. The fusionists backed Bryan, the Democratic nominee, but he lost again to McKinley, this time by a greater margin. The following year, Weaver was elected to office for the last time as the mayor of his hometown, Colfax, Iowa

Colfax is a city in Jasper County, Iowa, United States. Colfax is located approximately 24 miles east of Des Moines. The town was founded in 1866, and was named after Schuyler Colfax, vice president under Ulysses S. Grant. The population was 2,255 ...

, after defeating Republican P. H. Cragen and served in that position until 1903.

Later years, death, and legacy

The Republican Party's popularity after the victory in the

The Republican Party's popularity after the victory in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

led Weaver, for the first time, to doubt that populist values would eventually prevail. With the demise of the Populist Party, Weaver became a Democrat and was a delegate to the 1904 Democratic National Convention

The 1904 Democratic National Convention was an American presidential nominating convention that ran from July 6 through 10 in the Coliseum of the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall in St. Louis, Missouri. Breaking with eight years of control b ...

. He was displeased at the party's nominee, Alton B. Parker, whom he thought "plutocratic", but Weaver supported his unsuccessful campaign nevertheless. He gave serious consideration to running for the House again that year, but decided against it. In 1908, he supported Bryan's third campaign as the Democratic nominee for president, but it, too, was unsuccessful.

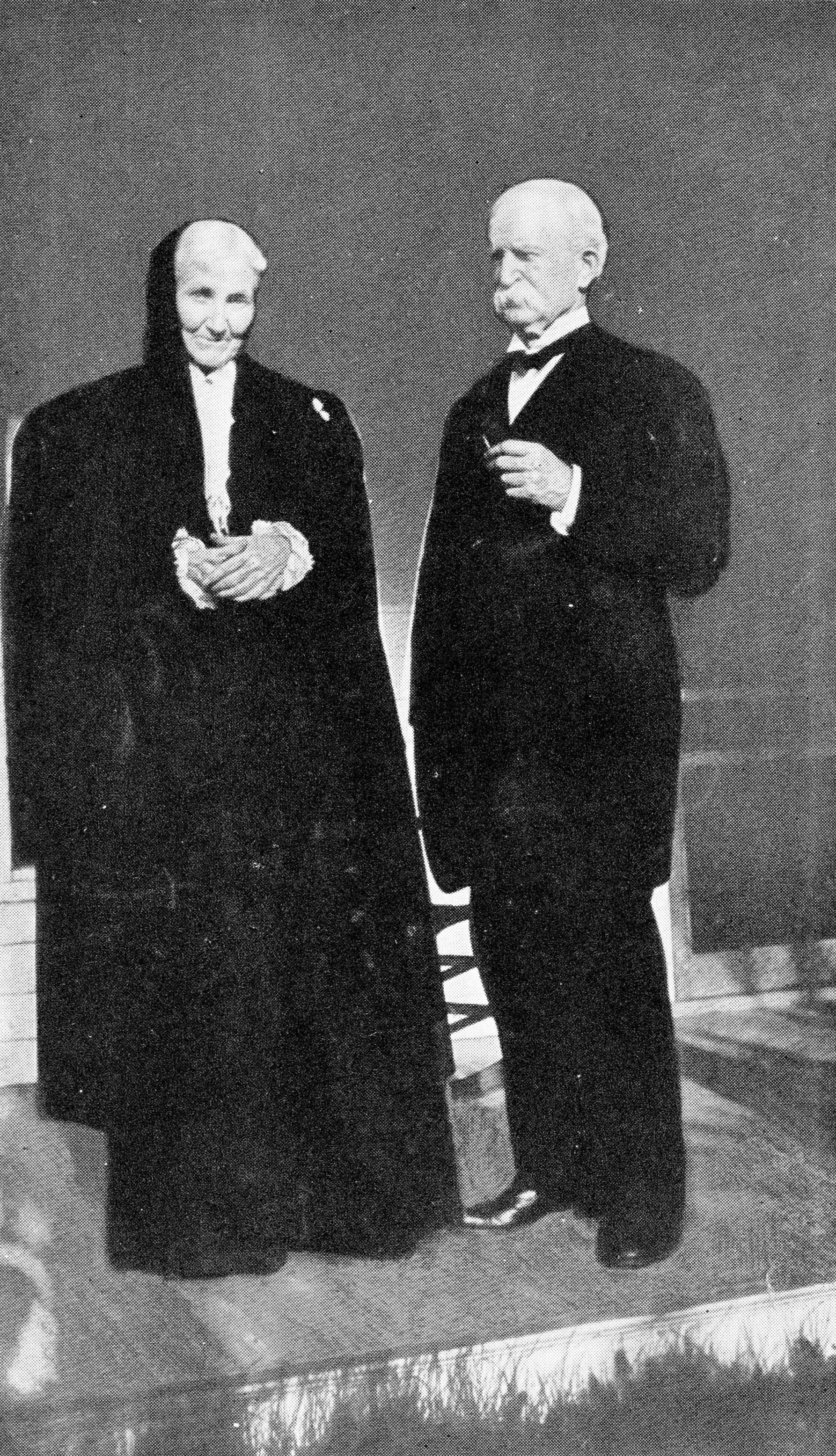

That same year, Weaver and his wife, Clara, celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary, surrounded by six of their children. The Iowa legislature honored him in 1909, and hung a portrait of him in the Iowa State Historical Building. He wrote a history of Jasper County, Iowa, where he lived, which was published in 1912. Weaver planned to campaign on behalf of Democratic candidates that year, but did not have the chance. On February 6 he died of heart failure at his daughter's house after being sick for ten days in Des Moines. After a funeral at the First Methodist Church in Des Moines, Weaver was buried in that city's Woodland Cemetery Woodland Cemetery may refer to:

* Woodland cemetery, a type of cemetery

or it may refer to specific places:

in Sweden

* Skogskyrkogården (The Woodland Cemetery) in Stockholm, Sweden

in the United States (by state)

* Woodland Cemetery (Quincy, I ...

. The last letter he wrote was an endorsement of Speaker of the House Champ Clark

James Beauchamp Clark (March 7, 1850March 2, 1921) was an American politician and attorney who represented Missouri in the United States House of Representatives and served as Speaker of the House from 1911 to 1919.

Born in Kentucky, he establis ...

for the Democratic presidential nomination, but he went on to lose the nomination to Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

.

Many of Iowa's leading statesmen, including Weaver's former adversaries, praised him at his funeral and in the years thereafter. Fusion with the Democrats had brought Populist policy into the mainstream, and several of the policies for which Weaver fought became law after his death, including the direct election of Senators, a graduated income tax, and a monetary policy not based on the gold standard; others, such as public ownership of the railroads and telephone companies, were never enacted. In a 2008 biography, Robert B. Mitchell wrote that "Weaver's legacy cannot be assessed using conventional measures", as much of what he fought for did not come to pass until after his death. Even so, Mitchell credits Weaver for beginning the political effort that led to those changes: "Weaver's most important legacy in national politics is not what he advocated, or how subsequent reforms worked, but his effect on America's continuing political conversation."

Notes

References

Sources

Books * * * * * * * * * Articles * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Retrieved on 13 February 2008 , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Weaver, James 1833 births 1912 deaths Burials at Woodland Cemetery (Des Moines, Iowa) Politicians from Dayton, Ohio Methodists from Iowa Iowa Republicans Iowa Greenbacks Greenback Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Iowa Iowa Populists Union Army generals People from Davis County, Iowa People from Colfax, Iowa Candidates in the 1880 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1892 United States presidential election Mayors of places in Iowa District attorneys in Iowa American social democrats People of Iowa in the American Civil War American abolitionists People from Cass County, Michigan People from Bloomfield, Iowa Greenback Party presidential nominees 19th-century American politicians American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Members of the Methodist Episcopal Church Iowa Democrats Methodist abolitionists Members of the United States House of Representatives from Iowa