Jacob Epstein (sculptor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

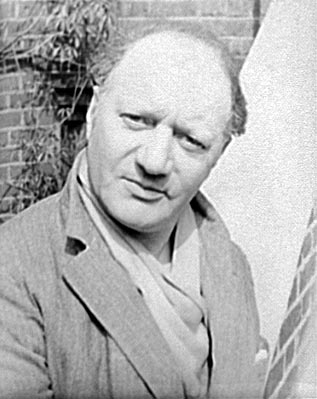

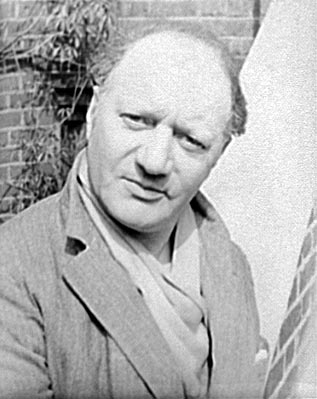

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American-British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a

In London, Epstein involved himself with a

In London, Epstein involved himself with a  London was not ready for Epstein's first major commission – 18 large nude sculptures made in 1908 for the façade of Charles Holden's building for the

London was not ready for Epstein's first major commission – 18 large nude sculptures made in 1908 for the façade of Charles Holden's building for the  Between 1913 and 1915, Epstein was associated with the short-lived Vorticism movement and produced one of his best known sculptures '' The Rock Drill''.

In 1915,

Between 1913 and 1915, Epstein was associated with the short-lived Vorticism movement and produced one of his best known sculptures '' The Rock Drill''.

In 1915,  In 1916, Epstein was commissioned by

In 1916, Epstein was commissioned by  Between the late 1930s and the mid-1950s, numerous works by Epstein were exhibited in

Between the late 1930s and the mid-1950s, numerous works by Epstein were exhibited in  Bronze portrait sculpture formed one of Epstein's staple products, and perhaps the best known. These sculptures were often executed with roughly textured surfaces, expressively manipulating small surface planes and facial details. Some fine examples are in the

Bronze portrait sculpture formed one of Epstein's staple products, and perhaps the best known. These sculptures were often executed with roughly textured surfaces, expressively manipulating small surface planes and facial details. Some fine examples are in the

, 1935, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, donated by

, 1935, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, donated by

Epstein died in August 1959 in

Epstein died in August 1959 in

File:Tomb of Oscar Wilde, Père Lachaise cemetery, Paris, France.jpg, '' Oscar Wilde's tomb'', 1912, Père Lachaise Cemetery,

9 artworks by Jacob Epstei

at th

Ben Uri

site

Jacob Epstein

An article on Jacob Epstein's work on The National Archives website. Includes references to files held at The National Archives.

Jon Cronshaw, ''Einstein captured in bronze as he fled''

Londonist.com – Jacob Epstein in London

(art and architecture) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Epstein, Jacob 1880 births 1959 deaths 20th-century British sculptors Académie Julian alumni American alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts American emigrants to England American expatriates in France American people of Polish-Jewish descent English Jews English male sculptors English people of Polish-Jewish descent English sculptors Jewish American artists Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People from Loughton Artists from New York City Jewish Legion Jewish sculptors

British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

in 1911.

He often produced controversial works which challenged ideas on what was appropriate subject matter for public artworks. He also made paintings and drawings, and often exhibited his work.

Early life and education

Epstein's parents, Max and Mary Epstein, were Polish Jewish refugees, living on New York'sLower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally an im ...

. His family was middle-class, and he was the third of five children. His interest in drawing came from long periods of illness; as a child he suffered from pleurisy.

He studied art in his native New York as a teenager, sketching the city, and joined the Art Students League of New York

The Art Students League of New York is an art school at 215 West 57th Street in Manhattan, New York City, New York. The League has historically been known for its broad appeal to both amateurs and professional artists.

Although artists may stu ...

in 1900. For his livelihood, he worked in a bronze foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

by day, studying drawing and sculptural modelling at night. Epstein's first major commission was to illustrate Hutchins Hapgood's 1902 book '' The Spirit of the Ghetto''. Epstein used the money from the commission to move to Paris.

Move to Europe

Moving to Europe in 1902, he studied in Paris at theAcadémie Julian

The Académie Julian () was a private art school for painting and sculpture founded in Paris, France, in 1867 by French painter and teacher Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907) that was active from 1868 through 1968. It remained famous for the number a ...

and the École des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts (; ) refers to a number of influential art schools in France. The term is associated with the Beaux-Arts style in architecture and city planning that thrived in France and other countries during the late nineteenth century ...

. He settled in London in 1905 and married Margaret Dunlop in 1906. Epstein became a British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

on 4 January 1911. Two other sources claim 1907. 5 6

Many of Epstein's works were sculpted at his two cottages in Loughton, Essex, where he lived first at number 49 then 50, Baldwin's Hill (there is a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

on number 50). During World War I he served briefly in the 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many wars ...

, known as the Jewish Legion

The Jewish Legion (1917–1921) is an unofficial name used to refer to five battalions of Jewish volunteers, the 38th to 42nd (Service) Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers in the British Army, raised to fight against the Ottoman Empire during ...

; following a breakdown, he was discharged in 1918 without having left England.

Work

In London, Epstein involved himself with a

In London, Epstein involved himself with a bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

and artistic crowd. Revolting against ornate, pretty art, he made bold, often harsh and massive forms of bronze or stone. His sculpture is distinguished by its vigorous rough-hewn realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

. Avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

in concept and style, his works often shocked his audience. This was not only a result of their (often explicit) sexual content, but also because they deliberately abandoned the conventions of classical Greek sculpture favoured by European academic sculptors, to experiment instead with the aesthetics of art traditions as diverse as those of India, China, ancient Greece, West Africa, and the Pacific Islands. People in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

nicknamed his nude male sculpture over the door of Lewis's department store (1954–56) "Dickie Lewis". Such factors may have focused disproportionate attention on certain aspects of Epstein's long and productive career, throughout which he aroused hostility, especially challenging taboos surrounding the depiction of sexuality.

British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headquar ...

on The Strand (now Zimbabwe House) were initially considered shocking to Edwardian

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

sensibilities, again mainly due to the perception that they were sexually over-explicit. In art-historical terms, however, the Strand sculptures were controversial for quite a different reason: they represented Epstein's first thoroughgoing attempt to break away from traditional European iconography in favour of elements derived from an alternative sculptural milieu – that of classical India. The female figures in particular may be seen deliberately to incorporate in no uncertain terms the posture and hand gestures of Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

and Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

art from the subcontinent. The current, mutilated condition of many of the sculptures is also not entirely connected with prudish censorship; the damage was caused in the 1930s when possibly dangerous projecting features were hacked off after pieces fell from one of the statues.

One of the most famous of Epstein's early commissions is '' Oscar Wilde's tomb'' in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, "which was condemned as indecent and at one point was covered in tarpaulin by the French police."

Between 1913 and 1915, Epstein was associated with the short-lived Vorticism movement and produced one of his best known sculptures '' The Rock Drill''.

In 1915,

Between 1913 and 1915, Epstein was associated with the short-lived Vorticism movement and produced one of his best known sculptures '' The Rock Drill''.

In 1915, John Quinn John or Jack Quinn may refer to:

Politicians and lawyers

*John Quinn (advocate) (1954–2022), Attorney General of the Isle of Man

*John Quinn (collector) (1870–1924), lawyer, collector of manuscripts and paintings, friend of T. S. Eliot and Ezr ...

, wealthy American collector and patron to the modernists, bought some Epstein sculptures to add to his private collection.

In 1916, Epstein was commissioned by

In 1916, Epstein was commissioned by Viscount Tredegar

Baron Tredegar, of Tredegar in the County of Monmouth, was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 16 April 1859 for the Welsh politician Sir Charles Morgan, 3rd Baronet, who had earlier represented Brecon in Parliame ...

to produce a bronze head of Newport poet W. H. Davies

William Henry Davies (3 July 1871 – 26 September 1940) was a Welsh poet and writer, who spent much of his life as a tramp or hobo in the United Kingdom and the United States, yet became one of the most popular poets of his time. His themes inc ...

. The bronze, regarded by many as the most accurate artistic impression of Davies and a copy of which Davies owned himself, may be found at Newport Museum and Art Gallery

Newport Museum and Art Gallery ( cy, Amgueddfa ac Oriel Gelf Casnewydd) (known locally as the City Museum ( cy, Amgueddfa Dinas)) is a museum, library and art gallery in the city of Newport, South Wales. It is located in Newport city centre on ...

In 1928, Epstein sculpted the head of the popular singer and film star Paul Robeson. A commission from Holden for the new headquarters building of the London Electric Railway

The London Electric Railway (LER) was an underground railway company operating three lines on the London Underground. It was formed in 1910 and existed until 1933, when it was merged into the London Passenger Transport Board.

History

The LER wa ...

generated another controversy in 1929. His nude sculptures ''Day'' and ''Night'' above the entrances of 55 Broadway

55 Broadway is a Grade I listed building close to St James's Park in London. Upon completion, it was the tallest office block in the city. In 1931 the building earned architect Charles Holden the RIBA London Architecture Medal. In 2020, it was ...

were again considered indecent and a debate raged for some time regarding demands to remove the offending statues which had been carved ''in-situ''. Eventually a compromise was reached to modify the smaller of the two figures represented on ''Day''. But the controversy affected his commissions for public work which dried up until World War II.

Between the late 1930s and the mid-1950s, numerous works by Epstein were exhibited in

Between the late 1930s and the mid-1950s, numerous works by Epstein were exhibited in Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the North West England, northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the Borough of Blackpool, borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, betw ...

. ''Adam'', ''Consummatum Est'', ''Jacob and the Angel and Genesis'', and other works, were initially displayed in an old drapery shop surrounded by red velvet curtains. The crowds were ushered in at the cost of a shilling by a barker on the street. After a small tour of American fun fairs, the works were returned to Blackpool and were exhibited in the anatomical curiosities section of Louis Tussaud

Louis Joseph Kenny Tussaud (1869–1938) was a great-grandson of Marie Tussaud, creator of the Madame Tussauds wax museums. He worked at Madame Tussauds museum as a wax figure sculptor but left when his brother John Theodore Tussaud became chief ...

's waxworks. The works were displayed alongside dancing marionettes, diseased body parts and conjoined ("Siamese") twin babies in jars. Placing Epstein within the context of freakish curiosity perhaps added to Epstein's decision not to create further large-scale direct carving

This page describe terms and jargon related to sculpture and sculpting.

__NOTOC__

A

armature

:An armature is an internal frame or skeleton which supports a modelled sculpture. A typical armature for a small sculpture is made of heavy gauge ...

s.

Bronze portrait sculpture formed one of Epstein's staple products, and perhaps the best known. These sculptures were often executed with roughly textured surfaces, expressively manipulating small surface planes and facial details. Some fine examples are in the

Bronze portrait sculpture formed one of Epstein's staple products, and perhaps the best known. These sculptures were often executed with roughly textured surfaces, expressively manipulating small surface planes and facial details. Some fine examples are in the National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

*National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

*National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London, with s ...

. Another example is the bust of the Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman that sat in the marble halls of Highbury for many years before being moved to the new Emirates Stadium

The Emirates Stadium (known as Arsenal Stadium for UEFA competitions) is a football stadium in Holloway, London, England. It has been the home stadium of Arsenal Football Club since its completion in 2006. It has a current seated capacity ...

.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Epstein was asked to undertake six commissions for the War Artists' Advisory Committee. After completing bronze busts of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham, General Sir Alan Cunningham

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War ...

, and Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

- and Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–19 ...

, Epstein accepted a commission to create busts of John Anderson John Anderson may refer to:

Business

*John Anderson (Scottish businessman) (1747–1820), Scottish merchant and founder of Fermoy, Ireland

* John Byers Anderson (1817–1897), American educator, military officer and railroad executive, mentor of ...

and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. He completed a bust of Winston Churchill in early 1947.

Epstein's aluminium figure of Christ in Majesty (1954–55), is suspended above the nave in Llandaff Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral ( cy, Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf) is an Anglican cathedral and parish church in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales. It is the seat of the Bishop of Llandaff, head of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff. It is dedicated to Saint Peter ...

, Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

, on a concrete arch designed by George Pace

George Gaze Pace, (31 December 1915 – 23 August 1975) was an English architect who specialised in ecclesiastical works.

He was trained in London, and served in the army, before being appointed as surveyor to a number of cathedrals. Mo ...

.

His larger sculptures were his most expressive and experimental, but also his most vulnerable. His depiction of Rima, one of author W. H. Hudson

William Henry Hudson (4 August 1841 – 18 August 1922) – known in Argentina as Guillermo Enrique Hudson – was an English Argentines, Anglo-Argentine author, natural history, naturalist and ornithology, ornithologist.

Life

Hudson was the ...

's most famous characters, graces a serene enclosure in Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

. Even here, a visitor became so outraged as to defile it with paint. He was one of 250 sculptors who exhibited in the 3rd Sculpture International

3rd Sculpture International was a 1949 exhibition of contemporary sculpture held inside and outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. It featured works by 250 sculptors from around the world, and ran from May 15 ...

, which was organised by the Fairmount Park Association (now the Association for Public Art

Established in 1872 in Philadelphia, the Association for Public Art (formerly Fairmount Park Art Association) is the United States' first private, nonprofit public art organization dedicated to integrating public art and urban planning. The Assoc ...

) and held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMoA) is an art museum originally chartered in 1876 for the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The main museum building was completed in 1928 on Fairmount, a hill located at the northwest end of the Benjamin Fr ...

in the summer of 1949.

Epstein would often sculpt the images of friends, casual acquaintances, and even people dragged from the street into his studio almost at random. He worked even on his dying day. He also painted; many of his watercolours and gouaches were of Epping Forest, where he lived (at Loughton) and sculpted. These were often exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in London. His ''Monkwood Autumn'' and ''Pool, Epping Forest'' date from 1944 to 1945.

Epstein was Jewish, and negative reviews of his work sometimes took on an antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

flavour, though he did not attribute the "average unfavorable criticism" of his work to antisemitism.

Epstein met Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

at Roughton Heath, Norfolk, in 1933 and had three sittings for a bust. He remembered his meeting with Einstein as, "His glance contained a mixture of the humane, the humorous and the profound. This was a combination which delighted me. He resembled the ageing Rembrandt."

Personal life

, 1935, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, donated by

, 1935, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, donated by Lawrence Ogilvie

Lawrence Ogilvie (5 July 1898 – 16 April 1980) was a Scottish plant pathologist.

From 1923, in his first job and aged only 25, when agriculture was Bermuda's major industry, Ogilvie identified the virus that had devastated the islands' high-v ...

in the 1980s

Despite being married to and continuing to live with Margaret, Epstein had a number of relationships with other women that brought him his five children: Peggy Jean (1918–2010), Theodore Garman, Theo (1924–1954), Kathleen (1926–2011), Esther (1929–1954) and Jackie (1934–2009). Margaret generally tolerated these relationships – even to the extent of bringing up his first and last children. In 1921, Epstein began the longest of these relationships, with Kathleen Garman

Kathleen Esther Garman, Lady Epstein (15 May 1901 – August 1979) was the third of the seven Garman sisters, who were high-profile members of artistic circles in mid-20th century London, renowned for their beauty and scandalous behaviour. She ...

, one of the Garman sisters, mother of his three middle children, which continued until his death. Margaret "tolerated Epstein's infidelities, allowed his models and lovers to live in the family home and raised Epstein's first child, Peggy Jean, who was the daughter of Meum Lindsell, one of Epstein's previous lovers, and his last, Jackie, whose mother was the painter Isabel Nicholas

Isabel Rawsthorne (born Isabel Nicholas, 10 July 1912 – 27 January 1992), also known at various times as Isabel Delmer and Isabel Lambert, was a British painter, scenery and costume designer, and occasional artists' model. During the Second ...

. Evidently, Margaret's tolerance did not extend to Epstein's relationship with Kathleen Garman, as in 1923 Margaret shot and wounded Kathleen in the shoulder."

Margaret Epstein died in 1947, and after Epstein was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

in the 1954 New Year Honours

The New Year Honours 1954 were appointments in many of the Commonwealth realms of Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced on 1 January 1954 to celebrat ...

, he married Kathleen Garman in 1955.

Their eldest daughter, also named Kathleen but known as "Kitty", married painter Lucian Freud in 1948 and was mother of his daughters Annie and Annabel. She is the subject of the painting ''Portrait of Kitty

''Portrait of Kitty'' is a painting by Lucian Freud of Kitty Garman, his wife and the eldest daughter of the sculptor Jacob Epstein and Kathleen Garman. Completed between 1948 and 1949, this oil on board measures .

Freud (1922–2011) was mar ...

''. In 1953 they divorced. She married a second time in 1955, to economist Wynne Godley. They have one daughter.

Death and legacy

Epstein died in August 1959 in

Epstein died in August 1959 in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

and is interred in Putney Vale Cemetery.

A blue plaque is found at "Deerhurst", 50 Baldwins Hill in Loughton, Epstein's home from 1933 to 1950.

The Garman Ryan Collection

The Garman Ryan Collection is a permanent collection of art works housed at The New Art Gallery Walsall and comprises 365 works of art, including prints, sketches, sculptures, drawings and paintings collected by Kathleen Garman (later wife of the ...

, including several works by Epstein, was donated in 1973 to the people of Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands County, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east ...

by Lady Epstein. It is on display at The New Art Gallery Walsall.

Epstein's art is to be found all over the world. Highly original for its time, it substantially influenced the younger generation of sculptors such as Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

and Barbara Hepworth

Dame Jocelyn Barbara Hepworth (10 January 1903 – 20 May 1975) was an English artist and sculptor. Her work exemplifies Modernism and in particular modern sculpture. Along with artists such as Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo, Hepworth was a leadi ...

. According to June Rose's biography, during the early 1920s Moore visited Epstein in his studio and was befriended by the older sculptor. Epstein, Moore, and Hepworth all expressed deep fascination with non-western art in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

In March 2000 the Epstein Estate appointed Tate Images as Copyright Agent for all permissions clearance.

Selected major pieces

* 1907–08 ''Ages of Man'',British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headquar ...

headquarters, Strand, London

Strand (or the Strand) is a major thoroughfare in the City of Westminster, Central London. It runs just over from Trafalgar Square eastwards to Temple Bar, where the road becomes Fleet Street in the City of London, and is part of the A4 ...

– mutilated/destroyed

* 1910 ''Rom'', limestone, Portrait of Romily Epstein, Welsh National Museum of Art, Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

, Wales.

* 1911–12 Oscar Wilde Memorial – Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris

* 1913–14 '' The Rock Drill'', bronze — the Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

Collection (symbolising 'the terrible Frankenstein's monster we have made ourselves into')

* 1917 ''Venus'' marble – Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

* 1919 ''Christ'' Bronze – Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead is a village and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, north of St Albans. The population of the ward at the 2001 census was 6,058. Included within the parish is the small hamlet of Amwell.

History

Settlements in this area were ...

, England

* 1921 ''Bust of Jacob Kramer

Jacob Kramer (26 December 1892 – 4 February 1962)''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' was a Russian Empire-born painter who spent all of his working life in England.

Early life

Jacob Kramer was born in the small town of Klintsy, then ...

'' - Leeds Art Gallery

Leeds Art Gallery in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, is a gallery, part of the Leeds Museums & Galleries group, whose collection of 20th-century British Art was designated by the British government in 1997 as a collection "of national importance" ...

, Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

* 1922–30 ''Head of Hans Kindler'' - Kemper Art Museum

The Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum is an art museum located on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis, within the university's Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. Founded in 1881 as the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts, it w ...

, St. Louis, MO

* 1924–25 W. H. Hudson Memorial, ''Rima'', Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is a Grade I-listed major park in Westminster, Greater London, the largest of the four Royal Parks that form a chain from the entrance to Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Pa ...

* 1926 Bronze bust of ''Ramsey MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

'', Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, London

* 1928–29 ''Night'' and ''Day'' Portland Stone – 55 Broadway

55 Broadway is a Grade I listed building close to St James's Park in London. Upon completion, it was the tallest office block in the city. In 1931 the building earned architect Charles Holden the RIBA London Architecture Medal. In 2020, it was ...

, St. James', London

* 1933 ''Head of Albert Einstein'' Bronze – Honolulu Museum of Art

* 1939 ''Adam'' Alabaster – Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the North West England, northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the Borough of Blackpool, borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, betw ...

, England; now at Harewood House

Harewood House ( , ) is a country house in Harewood, West Yorkshire, England. Designed by architects John Carr and Robert Adam, it was built, between 1759 and 1771, for Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, a wealthy West Indian plantation a ...

, near Leeds

* 1940–41 ''Jacob and the Angel'' Alabaster – the Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

Collection (originally controversially "anatomical")

* 1944– 45 ''The Archangel Lucifer'' - Bronze - Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

* 1947–48 ''Lazarus'' Hoptonwood Stone – Now in chapel of New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1379 by William of Wykeham in conjunction with Winchester College as its feeder school, New College is one of the oldest colleges at th ...

* 1950 ''Madonna and Child'' Bronze, Convent of the Holy Child Jesus, London

* 1954 ''Social Consciousness'' – University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

, Philadelphia

* 1954–55 ''Christ in Majesty'' – Aluminium – Llandaff Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral ( cy, Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf) is an Anglican cathedral and parish church in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales. It is the seat of the Bishop of Llandaff, head of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff. It is dedicated to Saint Peter ...

, Cardiff

* 1956 ''Liverpool Resurgent

''Liverpool Resurgent'' is an artwork by Jacob Epstein, mounted above the main entrance to the former Lewis's department store building in Ranelagh Street, Liverpool. It comprises a large bronze statue and three relief panels.

The current Lew ...

'' – Lewis's Building, Liverpool

* 1957 Bust of ''William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

'', Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, London

* 1958 St Michael's Victory over the Devil

''St Michael's Victory over the Devil'' is a 1958 bronze sculpture by Jacob Epstein, displayed on the south end of the east wall outside of the new Coventry Cathedral, above the steps leading up from Priory Street to the cathedral's entrance an ...

'' Bronze – Coventry Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Michael, commonly known as Coventry Cathedral, is the seat of the Bishop of Coventry and the Diocese of Coventry within the Church of England. The cathedral is located in Coventry, West Midlands, England. The curren ...

* 1959 ''The Rush of Green

''The Rush of Green'', also known as ''Pan'' or ''The Bowater House Group'', was the last sculpture completed by Jacob Epstein before his death at his home in Hyde Park Gate on 19 August 1959. The sculpture group includes a long-limbed family – ...

'' (also known as ''Pan'' or ''The Bowater House Group''), Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is a Grade I-listed major park in Westminster, Greater London, the largest of the four Royal Parks that form a chain from the entrance to Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Pa ...

Sculptures

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

File:Lilian Shelly, 1920. By Sir Jacob Epstein. Bronze. The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, UK.jpg, ''Lilian Shelly'', bronze, 1920, Burrell Collection, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, UK

File:Joseph Conrad, by Jacob Epstein.jpg, ''Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

'', 1924, National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London housing a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. It was arguably the first national public gallery dedicated to portraits in the world when it ...

Epstein, wrote Conrad, "has produced a wonderful piece of work of a somewhat monumental dignity, and yet—everybody agrees—the likeness is striking." Zdzisław Najder

Zdzisław Najder (; 31 October 1930 – 15 February 2021) was a Polish literary historian, critic, and political activist.

He was primarily known for his studies on Joseph Conrad, for his periods of service as political adviser to Lech Wałęsa ...

, ''Joseph Conrad: A Life'', Camden House, 2007, , p. 568.

File:The Hudson Memorial Bird Sanctuary.jpg, ''Hudson Memorial Bird Sanctuary'', 1924, Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is a Grade I-listed major park in Westminster, Greater London, the largest of the four Royal Parks that form a chain from the entrance to Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Pa ...

Image:The Visitation 03.jpg, ''The Visitation'', 1926, Queensland Art Gallery

The Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) is an art museum located in South Bank, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. The gallery is part of QAGOMA. It complements the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) building, situated only away.

The Queensland Art Gallery ...

Image:JacobEpstein DayAndNight.jpg, ''Day'' and ''Night'', Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

, 1928, London Electric Railway

The London Electric Railway (LER) was an underground railway company operating three lines on the London Underground. It was formed in 1910 and existed until 1933, when it was merged into the London Passenger Transport Board.

History

The LER wa ...

headquarters, 55 Broadway

55 Broadway is a Grade I listed building close to St James's Park in London. Upon completion, it was the tallest office block in the city. In 1931 the building earned architect Charles Holden the RIBA London Architecture Medal. In 2020, it was ...

When unveiled, the sculptures were considered too shocking.

Image:PM Einstein.JPG, ''Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

'', 1933, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

File:George Bernard Shaw, by Jacob Epstein, 1934.jpg, ''George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

'', 1934, National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London housing a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. It was arguably the first national public gallery dedicated to portraits in the world when it ...

Image:PM epstein lucifer.JPG, ''The Archangel Lucifer'', 1944–45, round gallery of Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Image:Liverpool Resurgent Epstein.jpg, ''Liverpool Resurgent

''Liverpool Resurgent'' is an artwork by Jacob Epstein, mounted above the main entrance to the former Lewis's department store building in Ranelagh Street, Liverpool. It comprises a large bronze statue and three relief panels.

The current Lew ...

'', 1956, Lewis's store, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

Image:Edward Sydney Woods by Epstein.jpg, ''Edward Sydney Woods

Edward Sydney Woods (1 November 187711 January 1953) was an Anglican bishop, the second Bishop of Croydon (a suffragan bishop in the Diocese of Southwark) from 1930 until 1937 and, from then until his death, the 94th Bishop of Lichfield.''Who wa ...

'', 1958, Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

File:GOC London Public Art 2 114 – The Rush of Green.jpg, ''Pan Statue'', also known as ''Rush of Green

''The Rush of Green'', also known as ''Pan'' or ''The Bowater House Group'', was the last sculpture completed by Jacob Epstein before his death at his home in Hyde Park Gate on 19 August 1959. The sculpture group includes a long-limbed family � ...

'', 1961, by Edinburgh Gate, south side of Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is a Grade I-listed major park in Westminster, Greater London, the largest of the four Royal Parks that form a chain from the entrance to Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Pa ...

Bibliography

* Epstein, Jacob, ''The sculptor speaks: Jacob Epstein toArnold L. Haskell

Arnold Lionel David Haskell (19 July 1903, London – 14 November 1980, Bath) was a British dance critic who founded the Camargo Society in 1930. With Ninette de Valois, he was influential in the development of the Royal Ballet School, later beco ...

, a series of conversations on art'' (London: W. Heinemann, 1931)

* Epstein, Jacob, ''Let there be sculpture: an autobiography'' (London: Michael Joseph, 1940)

Notes

References

*Further reading

Below is a brief overview of key texts relating to Epstein: * Buckle, Richard, ''Jacob Epstein: sculptor'' (London: Faber 1963) * Cork, Richard, ''Jacob Epstein'' (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1999) * Cronshaw, Jonathan, ''Carving a Legacy: The Identity of Jacob Epstein'' (PhD Thesis, University of Leeds, 2010) * Cronshaw, Jonathan, ''"this work was never commissioned at all": Jacob Epstein's Madonna and Child (1950–52)'', Art and Christianity 66, Summer 2011 * Friedman, Terry, '' 'The Hyde Park atrocity': Epstein's Rima: creation and controversy'' (Leeds: Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture, 1988) * Gardner, Stephen, ''Jacob Epstein: Artist Against the Establishment'' (London: Joseph, 1992) * Gilboa Raquel, ''...And There Was Sculpture; Epstein's Formative Years (1880–1930)'' (London, 2009) * Gilboa Raquel, ''...Unto heaven will I ascend; Jacob Epstein's Inspired Years (1930–1959)'' (London, 2013) * Gilboa Raquel, Epstein and 'Adam' Revisited, ''The British Art Journal'', Winter 2004, 73–79 * Gilboa Raquel, Jacob Epstein's model Meum: Unpublished drawings, ''The Burlington Magazine'', CXVII, 837–380 * Hapgood, Hutchins, ''The spirit of the ghetto: studies of the Jewish quarter of New York; with drawings from life by Jacob Epstein'' (New York; London: Funk and Wagnalls, 1909) * Silber, Evelyn, et al. ''Jacob Epstein: sculpture and drawings'', (Leeds: Leeds City Art Galleries; London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1987) * Silber, Evelyn, ''The Sculpture of Epstein'' (London, 1984) * Colin Turner, ''A Caricature of a Sculptor. Jacob Epstein and the British Press: a critical analysis of old history and new evidence'' (PhD Thesis, Loughborough University, 2009) * ''Carving mountains: modern stone sculptures in England 1907–37:Frank Dobson

Frank Gordon Dobson (15 March 1940 – 11 November 2019) was a British Labour Party politician. As Member of Parliament (MP) for Holborn and St. Pancras from 1979 to 2015, he served in the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Health from 1997 ...

, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill, (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as ″the greatest artist-cra ...

, Barbara Hepworth

Dame Jocelyn Barbara Hepworth (10 January 1903 – 20 May 1975) was an English artist and sculptor. Her work exemplifies Modernism and in particular modern sculpture. Along with artists such as Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo, Hepworth was a leadi ...

, Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

, Ben Nicholson, John Skeaping

John Rattenbury Skeaping, RA (9 June 1901 – 5 March 1980) was an English sculptor and equine painter and sculptor. He designed animal figures for Wedgwood, and his life-size statue of Secretariat is exhibited at the National Museum of R ...

'' (Cambridge: Kettles Yard, 1998)

* ''Embracing the Exotic: Jacob Epstein & Dora Gordine'' (Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, 2006)

External links

*9 artworks by Jacob Epstei

at th

Ben Uri

site

Jacob Epstein

An article on Jacob Epstein's work on The National Archives website. Includes references to files held at The National Archives.

Jon Cronshaw, ''Einstein captured in bronze as he fled''

Londonist.com – Jacob Epstein in London

(art and architecture) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Epstein, Jacob 1880 births 1959 deaths 20th-century British sculptors Académie Julian alumni American alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts American emigrants to England American expatriates in France American people of Polish-Jewish descent English Jews English male sculptors English people of Polish-Jewish descent English sculptors Jewish American artists Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People from Loughton Artists from New York City Jewish Legion Jewish sculptors