J. Hamilton Lewis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Hamilton Lewis (May 18, 1863 – April 9, 1939) was an American attorney and politician. Sometimes referred to as J. Ham Lewis or Ham Lewis, he represented

In 1921, 1922, and 1925, Lewis was part of the U.S. delegation to

In 1921, 1922, and 1925, Lewis was part of the U.S. delegation to

''The Two Great Republics Rome and the United States''

Chicago, IL: The Rand-McNally Press.

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. He was the first to hold the title of Whip

A whip is a tool or weapon designed to strike humans or other animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain. They can also be used without inflicting pain, for audiovisual cues, such as in equestrianism. They are generally ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

.

Born in Danville, Virginia

Danville is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, located in the Southside Virginia region and on the fall line of the Dan River. It was a center of tobacco production and was an area of Confederate activit ...

and raised in Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Geor ...

, Lewis attended several colleges, studied law, and attained admission to the bar in 1882. He moved to Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

in 1885, where he became active in politics as a Democrat; he served in the territorial legislature, worked with the federal commission that helped establish the U.S.-Canada boundary, and ran unsuccessfully for governor. He served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from 1897 to 1899.

After service in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Lewis relocated to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

. After serving as the city's corporation counsel, and running unsuccessfully for governor, Lewis won election to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

in 1912, and served one term (1913-1919). He was chosen to serve as Majority Whip

A whip is an official of a political party whose task is to ensure party discipline in a legislature. This means ensuring that members of the party vote according to the party platform, rather than according to their own individual ideolog ...

, and was the first person to hold this position. He ran unsuccessfully for reelection in 1918, and for governor in 1920. In 1930

Events

January

* January 15 – The Moon moves into its nearest point to Earth, called perigee, at the same time as its fullest phase of the Lunar Cycle. This is the closest moon distance at in recent history, and the next one will b ...

, he was again elected to the U.S. Senate, and served from 1931 until his death. He died in Washington, D.C., and was interred first in Arlington, Virginia

Arlington County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from the District of Columbia, of which it was once a part. The county ...

, and later at Fort Lincoln Cemetery

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''face ...

in Brentwood, Maryland

Brentwood is a town in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States.

Per the 2020 census, the population was 3,828. Brentwood is located within of Washington. The municipality of Brentwood is located just outside the northeast boundary o ...

.

Early life

Lewis was born inDanville, Virginia

Danville is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, located in the Southside Virginia region and on the fall line of the Dan River. It was a center of tobacco production and was an area of Confederate activit ...

on May 18, 1863, and grew up in Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Geor ...

. His mother had traveled to Virginia to nurse his father, who was wounded while serving for the Confederacy in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. His mother died in childbirth, and his father was left an invalid, so Lewis was raised by relatives. He attended Augusta's Houghton School, the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

, Ohio Northern University

Ohio Northern University (Ohio Northern or ONU) is a private United Methodist Church–affiliated university in Ada, Ohio. Founded by Henry Solomon Lehr in 1871, ONU is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission. It offers over 60 programs to ...

and Baylor University

Baylor University is a private Baptist Christian research university in Waco, Texas. Baylor was chartered in 1845 by the last Congress of the Republic of Texas. Baylor is the oldest continuously operating university in Texas and one of th ...

, and studied law in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

. He was admitted to the bar in 1882, and moved to Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

in 1885, where he continued to practice law. A Democrat, he served in Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

's legislature from 1887 to 1888. In 1889 and 1890, Lewis worked with the Joint High Commission on Canadian and Alaska Boundaries to present the U.S. position. He was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Washington

The governor of Washington is the head of government of Washington and commander-in-chief of the state's military forces.WA Const. art. III, § 2. The officeholder has a duty to enforce state laws,WA Const. art. III, § 5. the power to either a ...

in 1892.

Continued career

Lewis was one of the few politicians to represent two states in the United States Congress. He representedWashington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

(1897–1899) in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, and was an unsuccessful candidate for election in 1898. In 1899, he served as a U.S. Commissioner for regulating customs laws between the United States and Canada, and was an unsuccessful candidate for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. During the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Lewis served on the staff of the adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

of the Washington National Guard as an assistant inspector general with the rank of lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

. He was subsequently promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

, and served in a similar role in Cuba on the staff of John R. Brooke

John Rutter Brooke (July 21, 1838 – September 5, 1926) was one of the last surviving Union generals of the American Civil War when he died at the age of 88.

Early life

Brooke was born in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and was educated in nearby Co ...

, followed by service on the staff of Frederick Dent Grant

Frederick Dent Grant (May 30, 1850 – April 12, 1912) was a soldier and United States minister to Austria-Hungary. Grant was the first son of General and President of the United States Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Grant. He was named after his ...

.

In 1896, Lewis received 11 votes for the vice presidential nomination on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

despite not yet having attained the constitutionally required minimum age of 35. In 1900, he was an unsuccessful candidate for the Democratic vice presidential nomination; he withdrew before the balloting, and the nomination was won by Adlai Stevenson. In 1903, Lewis relocated to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, where he continued to practice law, and served as the city's corporation counsel from 1905 to 1907. In 1908, he was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Illinois

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

.

In 1913, Lewis was elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois; he served one term (1913–1919), and was the Majority Whip

A whip is an official of a political party whose task is to ensure party discipline in a legislature. This means ensuring that members of the party vote according to the party platform, rather than according to their own individual ideolog ...

for his entire term. In 1914, he was the Senate's representative at a London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

conference that considered way to ensure that laws and treaties guaranteeing safe sea travel could still be implemented as World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was beginning. Lewis also served as chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Department of State from 1915 to 1919. A close ally of President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, Lewis was a leader in getting much of Wilson's " New Freedom" legislation passed. Lewis also performed unspecified special wartime duties in Europe which led to him receiving knighthoods from the kings of Belgium and Greece. In October 1918, Lewis was aboard an army ship, USS ''Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

'', when it was hit by German fire. Lewis and others survived the blast, but 35 of the ship's crewmen perished.

Upon his defeat for reelection in 1918, Lewis was offered the ambassadorship to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, but he declined and returned private legal practice in Chicago, Illinois. In 1920, he ran unsuccessfully for governor. He eventually became a partner in the newly named Lewis, Adler, Lederer & Kahn (now known as Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr, LLP

Saul Ewing LLP is a U.S.-based law firm with 16 offices and approximately 400 attorneys providing a broad range of legal services. Its offices are located along the East Coast from Boston to Miami and extend into the Midwest by way of Chicago.

...

).

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

conferences held to settle wartime damage claims.

Later career

In1930

Events

January

* January 15 – The Moon moves into its nearest point to Earth, called perigee, at the same time as its fullest phase of the Lunar Cycle. This is the closest moon distance at in recent history, and the next one will b ...

, Lewis was again elected to the Senate; he was reelected in 1936

Events

January–February

* January 20 – George V of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India, dies at his Sandringham Estate. The Prince of Wales succeeds to the throne of the United Kingdom as King E ...

and served from March 4, 1931 until his death. He again served as the Majority Whip, this time from 1933 until his death. In addition, he was chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in Executive Departments from 1933 until his death.

In 1932, Lewis went to the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

in Chicago, as the "favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

" candidate of Illinois, at the behest of Chicago mayor Anton Cermak

Anton Joseph Cermak ( cs, Antonín Josef Čermák, ; May 9, 1873 – March 6, 1933) was an American politician who served as the 44th mayor of Chicago, Illinois from April 7, 1931 until his death on March 6, 1933. He was killed by an assassin, ...

. Cermak's hope was to use Lewis to keep the Illinois delegates from supporting Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, but Lewis later withdrew his name from consideration and released his delegates, many of whom went to FDR and helped secure him the nomination.

As a member of the foreign relations committee, he told the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

in 1938 that Hitler was not going to fight over Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

saying, "(Czechoslovakia) is a small matter than could be settled at any time." Sixteen days later Hitler annexed parts of Czechoslovakia, with the assent of Great Britain and France.

Lewis was one of the first to befriend Harry S. Truman after Truman's election to the Senate. During Truman's first few weeks in office in 1935, Lewis sat next to Truman and advised him: "Harry, don't start out with an inferiority complex. For the first six months you'll wonder how the hell you got here. After that you'll wonder how the hell rest of us got here."

Personal life

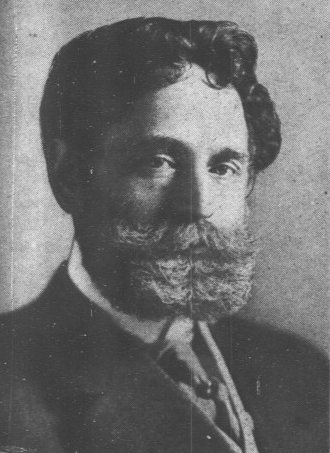

In 1896, Lewis married Rose Lawton Douglas (1871–1972). Lewis was known to be something of an eccentric in manner and dress, wearing spats well into the 1930s even though they were out of fashion, and sporting Van Dyke whiskers during an era when most men were clean shaven, as well as a collection of "wavy pink toupees". He was courtly in manner, and while some considered him verbose, he was generally acknowledged to be a talented orator.Death and burial

Lewis died at Garfield Hospital inWashington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morg ...

, and his funeral service was held in the Senate Chamber. He was interred at the Abbey Mausoleum near Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

; he was later reinterred at Fort Lincoln Cemetery

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''face ...

in Brentwood, Maryland

Brentwood is a town in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States.

Per the 2020 census, the population was 3,828. Brentwood is located within of Washington. The municipality of Brentwood is located just outside the northeast boundary o ...

.

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

* List ...

References

Sources

Books

* * * *Lewis, James Hamilton (1913)''The Two Great Republics Rome and the United States''

Chicago, IL: The Rand-McNally Press.

Magazines

*External links

* * * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Lewis, J. Hamilton 1863 births 1939 deaths 20th-century American politicians Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Washington (state) Democratic Party United States senators from Illinois Illinois Democrats Politicians from Augusta, Georgia Politicians from Danville, Virginia Candidates in the 1912 United States presidential election Members of the Washington Territorial Legislature Georgia (U.S. state) lawyers Washington (state) lawyers Washington National Guard personnel People born in the Confederate States