Italian invasion of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Italian invasion of France (10ŌĆō25 June 1940), also called the Battle of the Alps, was the first major

During the late 1920s, the Italian

During the late 1920s, the Italian  In October 1938, in the aftermath of the

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the  In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

On 1 September 1939,

On 1 September 1939,

On 10 June, Ciano informed his ambassadors in London and Paris that a declaration of war would be handed to the British and French ambassadors in Rome at 1630 hours, local time. When Ciano presented the declaration, the French ambassador,

On 10 June, Ciano informed his ambassadors in London and Paris that a declaration of war would be handed to the British and French ambassadors in Rome at 1630 hours, local time. When Ciano presented the declaration, the French ambassador,

In June 1940, only five Alpine passes between France and Italy were practicable for motor vehicles: the Little Saint Bernard Pass, the

In June 1940, only five Alpine passes between France and Italy were practicable for motor vehicles: the Little Saint Bernard Pass, the

During the 1930s, the French had constructed a series of fortificationsŌĆöthe

During the 1930s, the French had constructed a series of fortificationsŌĆöthe

During the interwar years and 1939, the strength of the Italian military had dramatically fluctuated due to waves of mobilization and demobilization. By the time Italy entered the war, over 1.5 million men had been mobilized. The

During the interwar years and 1939, the strength of the Italian military had dramatically fluctuated due to waves of mobilization and demobilization. By the time Italy entered the war, over 1.5 million men had been mobilized. The  Marshal

Marshal

*

Marshal Graziani, as army chief of staff, went to the front to take over the general direction of the war after 10 June. He was joined by the under-secretary of war, General

Marshal Graziani, as army chief of staff, went to the front to take over the general direction of the war after 10 June. He was joined by the under-secretary of war, General

On 16 June, Marshal Graziani gave the order for offensive operations to begin within ten days. Three actions were planned: Operation ''B'' through the Little Saint Bernard Pass, Operation ''M'' through the Maddalena Pass and Operation ''R'' along the

On 16 June, Marshal Graziani gave the order for offensive operations to begin within ten days. Three actions were planned: Operation ''B'' through the Little Saint Bernard Pass, Operation ''M'' through the Maddalena Pass and Operation ''R'' along the

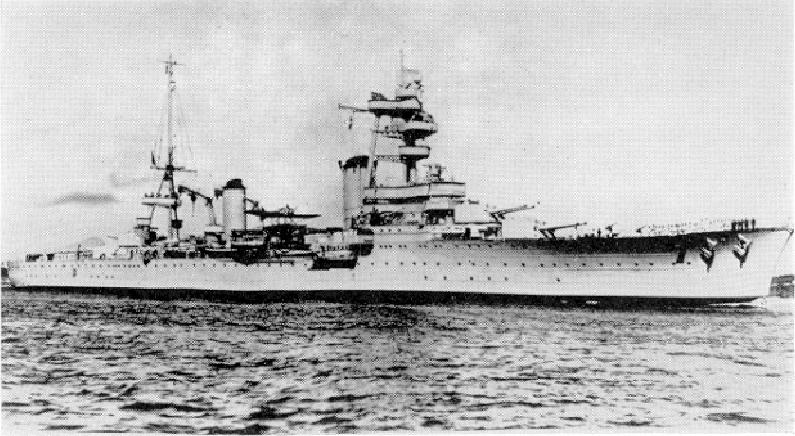

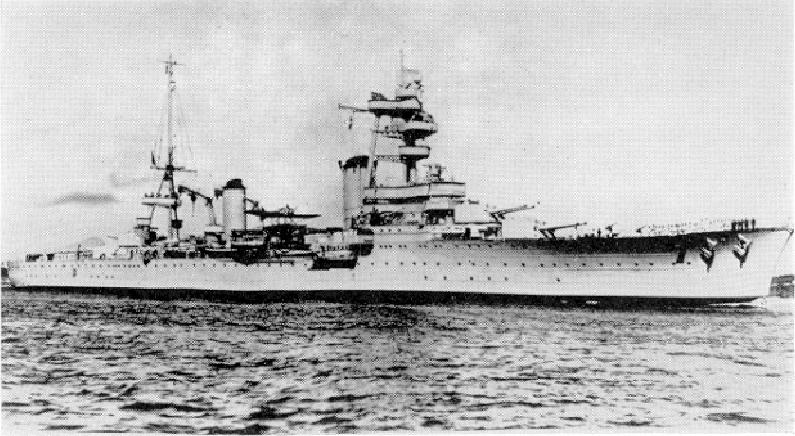

On 13 June, the ''Marine Nationale '' launched Operation Vado. The French 3rd Squadron comprised four

On 13 June, the ''Marine Nationale '' launched Operation Vado. The French 3rd Squadron comprised four ' s attack, on the Italian side it was claimed that this ship's counterattack, together with the reaction by the coastal batteries, had induced the enemy squadron to withdraw. Lieutenant Brignole was awarded the Giuseppe Brignole ŌĆō Marina Militare.

/ref> In coordination with the ''Marine Nationale'', eight Lior├® et Olivier LeO 45s of the ''Arm├®e de l'Air'' bombed Italian aerodromes, and nine

On 20 June, the guns of the Italian fort atop

On 20 June, the guns of the Italian fort atop

The main Italian attack was by the 4th Army under General

The main Italian attack was by the 4th Army under General ' s motorcycle battalion broke through the pass and began a rapid advance for . They then forded a river under heavy machine gun fire, while Italian engineers repaired the demolished bridge, suffering heavy losses in the process.

On 22 June, the ''Trieste''' s tank battalion passed the motorcycles and was stopped at a minefield. Two L3s became entrapped in barbed wire and of those following, one struck a landmine trying to go around the leading two, another fell into a ditch doing the same and the remaining two suffered engine failure. That same day, a battalion of the 65th Motorised Infantry Regiment of the ''Trieste'' Division was met by French infantry and field fortifications while trying to attack the ''Redoute'' from the rear. A machine gun unit relieved them and they abandoned the assault, continuing instead to S├®ez. The left column of the Alpine Corp met only weak resistance and attained the right bank of the

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

engagement of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great power ...

and the last major engagement of the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May ŌĆō 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

.

The Italian entry into the war widened its scope considerably in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. The goal of the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, was the elimination of Anglo-French domination in the Mediterranean, the reclamation of historically Italian territory (''Italia irredenta

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

'') and the expansion of Italian influence over the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and in Africa. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

tried during the 1930s to draw Mussolini away from an alliance with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

but the rapid German successes from 1938 to 1940 made Italian intervention on the German side inevitable by May 1940.

Italy declared war on France and Britain on the evening of 10 June, to take effect just after midnight. The two sides exchanged air raids on the first day of the war, but little transpired on the Alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National P ...

front since France and Italy had defensive strategies. There was some skirmishing between patrols and the French forts of the '' Ligne Alpine'' exchanged fire with their Italian counterparts of the '' Vallo Alpino''. On 17 June, France announced that it would seek an armistice with Germany. On 21 June, with a Franco-German armistice about to be signed, the Italians launched a general offensive along the Alpine front, the main attack coming in the northern sector and a secondary advance along the coast. The Italian offensive penetrated a few kilometres into French territory against strong resistance but stalled before its primary objectives could be attained, the coastal town of Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-C├┤te d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

, situated directly on the Italian border, being the most significant conquest.

On the evening of 24 June, an armistice was signed at Rome. It came into effect just after midnight on 25 June, at the same time as the armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compi├©gne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

(signed 22 June). Italy was allowed to occupy the territory it had captured in the brief fighting, a demilitarised zone was created on the French side of the border, Italian economic control was extended into south-east France up to the Rh├┤ne

The Rh├┤ne ( , ; wae, Rotten ; frp, R├┤no ; oc, R├▓se ) is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea. At Ar ...

and Italy obtained certain rights and concessions in certain French colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

. An armistice control commission, the (CIAF), was set up in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

to oversee French compliance.

Between August 1944 and May 1945, French forces again faced Italian troops along the Alpine frontier. The French managed to reoccupy all the lost territory in the Second Battle of the Alps (AprilŌĆōMay 1945).

Background

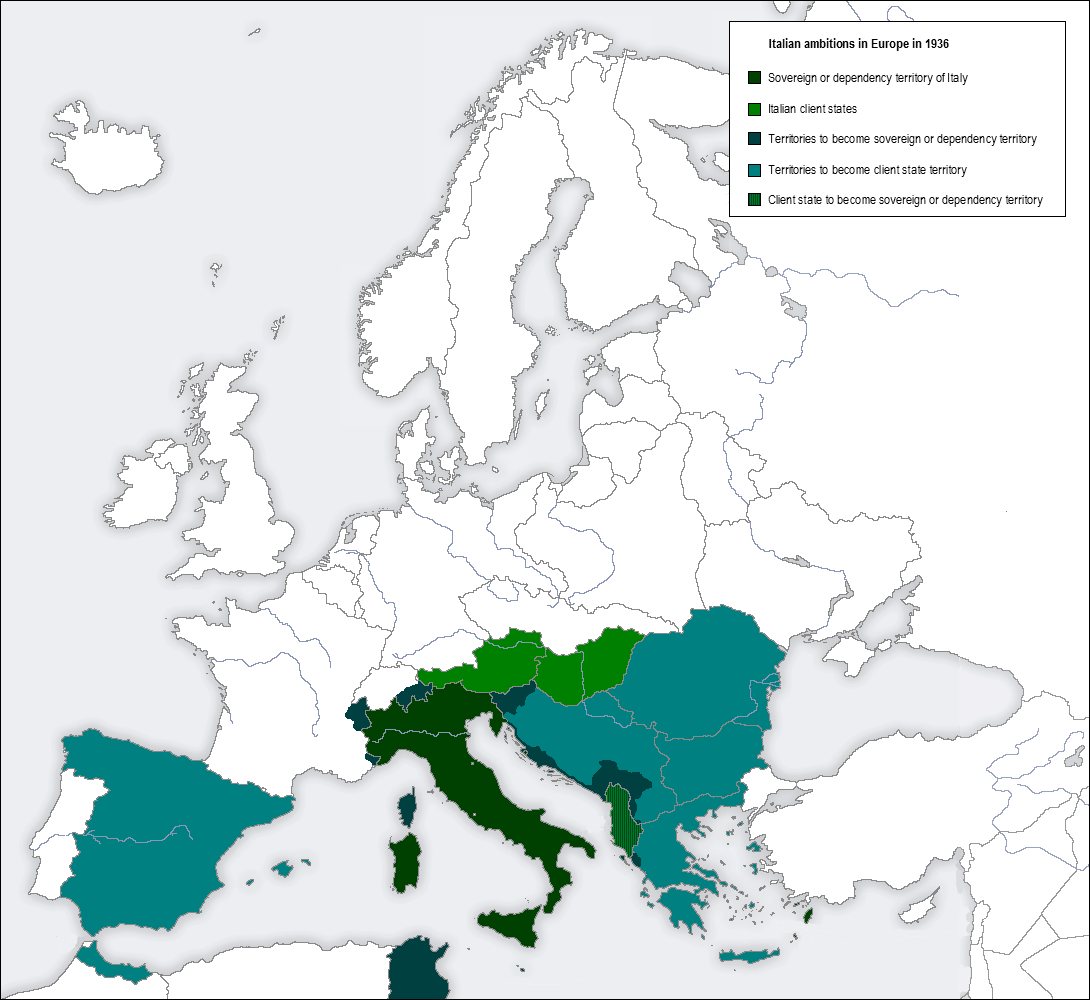

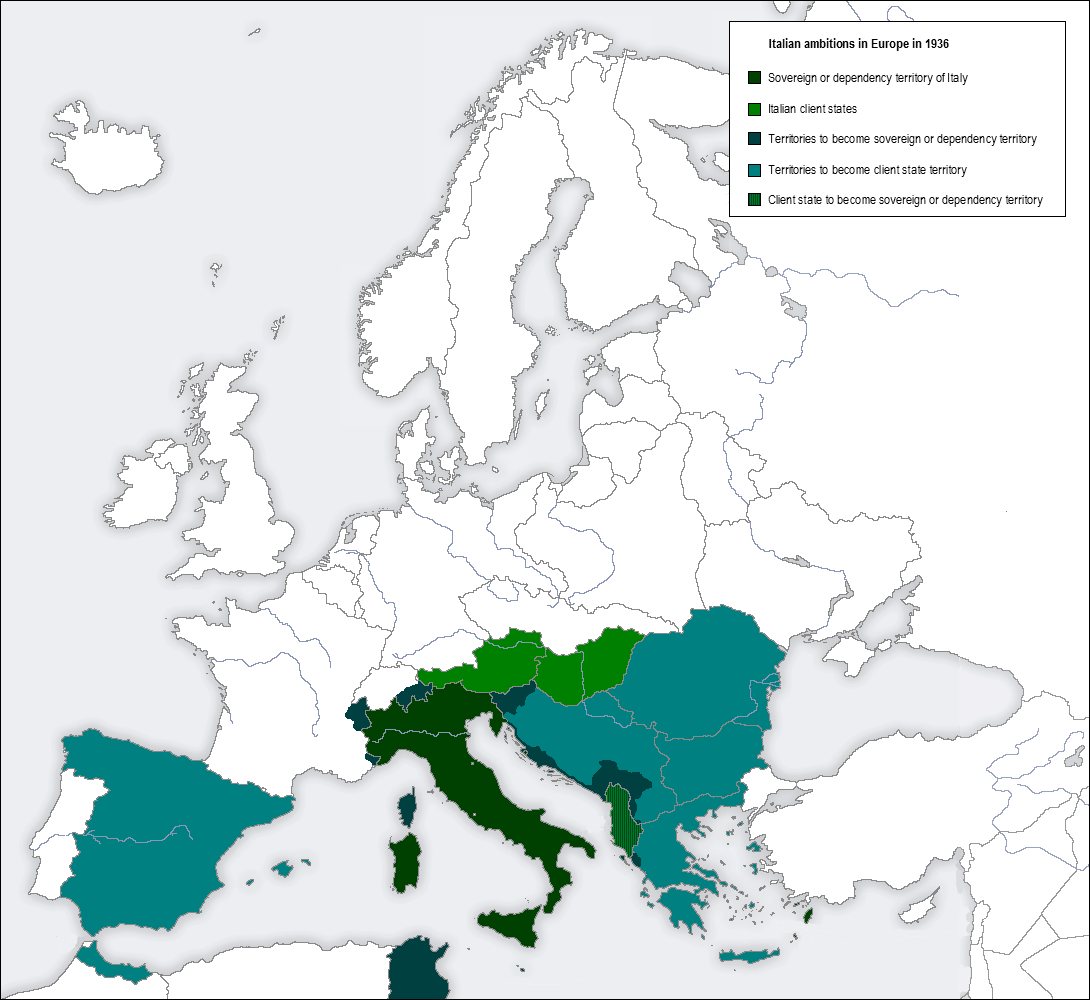

Italian imperial ambitions

During the late 1920s, the Italian

During the late 1920s, the Italian Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

spoke with increasing urgency about imperial expansion, arguing that Italy needed an outlet for its " surplus population" and that it would therefore be in the best interests of other countries to aid in this expansion. The immediate aspiration of the regime was political "hegemony in the MediterraneanŌĆōDanubianŌĆōBalkan region", more grandiosely Mussolini imagined the conquest "of an empire stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, ┘ģžČ┘Ŗ┘é ž¼ž©┘ä žĘž¦ž▒┘é, MaßĖŹ─½q Jabal ß╣¼─üriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

to the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( fa, ž¬┘å┌»┘ć ┘ćž▒┘ģž▓ ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' ar, ┘ģ┘ÄžČ┘Ŗ┘é ┘ć┘Åž▒┘ģ┘Åž▓ ''MaßĖŹ─½q Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the o ...

". Balkan and Mediterranean hegemony was predicated by ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753ŌĆō50 ...

dominance in the same regions. There were designs for a protectorate over Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

and for the annexation of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, as well as economic and military control of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, ąłčāą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčśą░ ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, ąłčāą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčśą░ ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszl├Īvia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, ą«ą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčÅ, translit=Juhoslavij ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. The regime also sought to establish protective patronŌĆōclient relationships with Austria

Austria, , bar, Ûstareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarorsz├Īg ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, ąæčŖą╗ą│ą░čĆąĖčÅ, BŪÄlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, which all lay on the outside edges of its European sphere of influence. Although it was not among his publicly proclaimed aims, Mussolini wished to challenge the supremacy of Britain and France in the Mediterranean Sea, which was considered strategically vital, since the Mediterranean was Italy's only conduit to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

s.

In 1935, Italy initiated the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922ŌĆō1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

, "a nineteenth-century colonial campaign waged out of due time". The campaign gave rise to optimistic talk on raising a native Ethiopian army "to help conquer" Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, ž¦┘äž│┘łž»ž¦┘å ž¦┘äžź┘åž¼┘ä┘Ŗž▓┘Ŗ ž¦┘ä┘ģžĄž▒┘Ŗ ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

. The war also marked a shift towards a more aggressive Italian foreign policy and also "exposed hevulnerabilities" of the British and French. This in turn created the opportunity Mussolini needed to begin to realize his imperial goals. In 1936, the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Espa├▒ola)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revoluci├│n, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

broke out. From the beginning, Italy played an important role in the conflict. Their military contribution was so vast, that it played a decisive role in the victory of the Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

forces led by Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 ŌĆō 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

. Mussolini had engaged in "a full-scale external war" due to the insinuation of future Spanish subservience to the Italian Empire, and as a way of placing the country on a war footing and creating "a warrior culture". The aftermath of the war in Ethiopia saw a reconciliation of German-Italian relations following years of a previously strained relationship, resulting in the signing of a treaty of mutual interest in October 1936. Mussolini referred to this treaty as the creation of a Berlin-Rome Axis, which Europe would revolve around. The treaty was the result of increasing dependence on German coal following League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Soci├®t├® des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

sanctions, similar policies between the two countries over the conflict in Spain, and German sympathy towards Italy following European backlash to the Ethiopian War. The aftermath of the treaty saw the increasing ties between Italy and Germany, and Mussolini falling under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's influence from which "he never escaped".

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovsk├Ī dohoda; sk, Mn├Łchovsk├Ī dohoda; german: M├╝nchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, Italy demanded concessions from France. These included a free port

Free economic zones (FEZ), free economic territories (FETs) or free zones (FZ) are a class of special economic zone (SEZ) designated by the trade and commerce administrations of various countries. The term is used to designate areas in which co ...

at Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, ž¼┘Ŗž©┘łž¬┘Ŗ ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

, control of the Addis AbabaŌĆōDjibouti railway

The Addis AbabaŌĆōDjibouti Railway (; , , ) is a new standard gauge international railway that serves as the backbone of the new Ethiopian National Railway Network. The railway was inaugurated by Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn on January ...

, Italian participation in the management of Suez Canal Company

Suez ( ar, ž¦┘äž│┘ł┘Ŗž│ '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

, some form of French-Italian condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

over French Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia (french: Protectorat fran├¦ais de Tunisie; ar, ž¦┘䞣┘ģž¦┘Ŗž® ž¦┘ä┘üž▒┘åž│┘Ŗž® ┘ü┘Ŗ ž¬┘ł┘åž│ '), commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial Empire era, ...

, and the preservation of Italian culture on Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, C├▓rsega; sc, C├▓ssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

with no French assimilation of the people. The French refused the demands, believing the true Italian intention was the territorial acquisition of Nice

Nice ( , ; Ni├¦ard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, ╬Ø╬»╬║╬▒╬╣╬▒; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative ...

, Corsica, Tunisia, and Djibouti. On 30 November 1938, Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 ŌĆō 11 January 1944) was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law, Benito Mussolini, from 1936 until 1 ...

addressed the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon Res ...

on the "natural aspirations of the Italian people" and was met with shouts of "Nice! Corsica! Savoy! Tunisia! Djibouti! Malta!" Later that day, Mussolini addressed the Fascist Grand Council

The Grand Council of Fascism (, also translated "Fascist Grand Council") was the main body of Mussolini's Fascist government in Italy, that held and applied great power to control the institutions of government. It was created as a body of the ...

"on the subject of what he called the immediate goals of 'Fascist dynamism'." These were Albania; Tunisia; Corsica, an integral part of France; the Ticino

Ticino (), sometimes Tessin (), officially the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino,, informally ''Canton Ticino'' ; lmo, Canton Tesin ; german: Kanton Tessin ; french: Canton du Tessin ; rm, Chantun dal Tessin . ...

, a canton of Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

; and all "French territory east of the River Var", including Nice, but not Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savou├© ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphin├® in the south.

Sa ...

.

Beginning in 1939 Mussolini often voiced his contention that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty. On 4 February 1939, Mussolini addressed the Grand Council in a closed session. He delivered a long speech on international affairs and the goals of his foreign policy, "which bears comparison with Hitler's notorious disposition, minuted by Colonel Hossbach". He began by claiming that the freedom of a country is proportional to the strength of its navy. This was followed by "the familiar lament that Italy was a prisoner in the Mediterranean". He called Corsica, Tunisia, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, K─▒br─▒s (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

"the bars of this prison", and described Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

and Suez as the prison guards. To break British control, her bases on Cyprus, Gibraltar, Malta, and in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, ┘ģžĄž▒ , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

(controlling the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, ┘é┘Ä┘å┘Äž¦ž®┘Å ┘▒┘äž│┘Å┘æ┘ł┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æž│┘É, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

) would have to be neutralized. On 31 March, Mussolini stated that "Italy will not truly be an independent nation so long as she has Corsica, Bizerta

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, ž©┘åž▓ž▒ž¬, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Biz├®rte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

, Malta as the bars of her Mediterranean prison and Gibraltar and Suez as the walls." Fascist foreign policy took for granted that the democraciesŌĆöBritain and FranceŌĆöwould someday need to be faced down. Through armed conquest Italian North Africa

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ┘ä┘Ŗž©┘Ŗž¦, L─½by─ü al-─¬ß╣Ł─ül─½ya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy (1922ŌĆō1943), Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the co ...

and Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the S ...

ŌĆöseparated by the Anglo-Egyptian SudanŌĆöwould be linked, and the Mediterranean prison destroyed. Then, Italy would be able to march "either to the Indian Ocean through the Sudan and Abyssinia, or to the Atlantic by way of French North Africa".

As early as September 1938, the Italian military had drawn up plans to invade Albania. On 7 April, Italian forces landed in the country and within three days had occupied the majority of the country. Albania represented a territory Italy could acquire for "'living space' to ease its overpopulation" as well as the foothold needed to launch other expansionist conflicts in the Balkans. On 22 May 1939, Italy and Germany signed the Pact of Steel

The Pact of Steel (german: Stahlpakt, it, Patto d'Acciaio), formally known as the Pact of Friendship and Alliance between Germany and Italy, was a military and political alliance between Italy and Germany.

The pact was initially drafted as a t ...

joining both countries in a military alliance. The pact was the culmination of German-Italian relations from 1936 and was not defensive in nature. Rather, the pact was designed for a "joint war against France and Britain", although the Italian hierarchy held the understanding that such a war would not take place for several years. However, despite the Italian impression, the pact made no reference to such a period of peace and the Germans proceeded with their plans to invade Poland.

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte (river), Rotte'') is the second largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the Prov ...

, was declared contraband. The Germans promised to keep up shipments by train, over the Alps, and Britain offered to supply all of Italy's needs in exchange for Italian armaments. The Italians could not agree to the latter terms without shattering their alliance with Germany. On 2 February 1940, however, Mussolini approved a draft contract with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

to provide 400 Caproni

Caproni, also known as ''Societ├Ā de Agostini e Caproni'' and ''Societ├Ā Caproni e Comitti'', was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Its main base of operations was at Taliedo, near Linate Airport, on the outskirts of Milan.

Founded by Giovan ...

aircraft; yet he scrapped the deal on 8 February. The British intelligence officer, Francis Rodd, believed that Mussolini was persuaded to reverse policy by German pressure in the week of 2ŌĆō8 February, a view shared by the British ambassador in Rome, Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 ŌĆō 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from ...

. On 1 March, the British announced that they would block all coal exports from Rotterdam to Italy. Italian coal was one of the most discussed issues in diplomatic circles in the spring of 1940. In April Britain began strengthening their Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

to enforce the blockade. Despite French misgivings, Britain rejected concessions to Italy so as not to "create an impression of weakness". Germany supplied Italy with about one million tons of coal a month beginning in the spring of 1940, an amount that even exceeded Mussolini's demand of August 1939 that Italy receive six million tons of coal for its first twelve months of war.

Battle of France

On 1 September 1939,

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September ŌĆō 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

. Following a month of war, Poland was defeated. A period of inaction, called the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Dr├┤le de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

, then followed between the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and Germany. On 10 May 1940, this inactivity ended as Germany began ''Fall Gelb

(Case Yellow), the invasion of France and the Low Countries

, scope = Strategic

, type =

, location = South-west Netherlands, central Belgium, northern France

, coordinates =

, planned = 1940

, planned_by = Erich von ...

'' (Case Yellow) against France and the neutral nations of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, L├½tzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duch├® de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Gro├¤herzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

. On 13 May, the Germans fought the Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, ...

and crossed the Meuse. The Germans rapidly encircled the northern Allied armies. On 27 May, Anglo-French forces trapped in the north began the Dunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allies of World War II, Allied soldiers during the World War II, Second World War from the bea ...

, abandoning their heavy equipment in the process. Following the Dunkirk evacuation, the Germans continued their offensive towards Paris with ''Fall Rot

''Fall Rot'' (Case Red) was the plan for a German military operation after the success of (Case Yellow), the Battle of France, an invasion of the Benelux countries and northern France. The Allied armies had been defeated and pushed back in th ...

'' (Case Red). With over 60 divisions, compared to the remaining 40 French divisions in the north, the Germans were able to breach the French defensive line along the river Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

by 6 June. Two days later, Parisians could hear distant gunfire. On 9 June, the Germans entered Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

, in Upper Normandy

Upper Normandy (french: Haute-Normandie, ; nrf, ─ż├óote-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Upper and Lower Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

History

It was created in 1956 from two d ...

. The following day, the French Government abandoned Paris, declaring it an open city

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open the opposing military will b ...

, and fled to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bord├©u ; eu, Bordele; it, Bord├▓; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

.

Italian declaration of war

On 23 January 1940, Mussolini remarked that "even today we could undertake and sustain a ... parallel war", having in mind a war withYugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, ąłčāą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčśą░ ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, ąłčāą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčśą░ ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszl├Īvia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, ą«ą│ąŠčüą╗ą░ą▓ąĖčÅ, translit=Juhoslavij ...

, since on that day Ciano had met with the dissident Croat Ante Paveli─ć

Ante Paveli─ć (; 14 July 1889 ŌĆō 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Usta┼Īe in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croatia ( hr, l ...

. A war with Yugoslavia was considered likely by the end of April. On 26 May, Mussolini informed Marshals

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 ŌĆō 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, chief of the Supreme General Staff, and Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 ŌĆō 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

that he intended to join the German war against Britain and France, so to be able to sit at the peace table "when the world is to be apportioned" following an Axis victory. The two marshals unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Mussolini that this was not a wise course of action, arguing that the Italian military was unprepared, divisions were not up to strength, troops lacked equipment, the empire was equally unprepared, and the merchant fleet was scattered across the globe. On 5 June, Mussolini told Badoglio, "I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought". According to the post-war memoires of Paul Paillole, in 1940 a captain in the French military intelligence, the Deuxi├©me Bureau

The Deuxi├©me Bureau de l'├ētat-major g├®n├®ral ("Second Bureau of the General Staff") was France's external military intelligence agency from 1871 to 1940. It was dissolved together with the Third Republic upon the armistice with Germany. Howeve ...

, he was forewarned about the Italian declaration of war on 6 June, when he met Major Navale, an Italian intelligence officer, on the Pont Saint-Louis to negotiate an exchange of captured spies. When Paillole refused Navale's proposal, the major warned him that they only had four days to work something out before war would be declared, although nothing much would happen near Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-C├┤te d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

before 19/20 June.

By mid-1940 Germany had revised its earlier preference for Italy as a war ally. The pending collapse of France might have been affected by any diversion of German military resources to support a new Alpine front. From a political and economic perspective, Italy was useful as a sympathetic neutral and her entry into the war might complicate any peace negotiations with Britain and France.

On 10 June, Ciano informed his ambassadors in London and Paris that a declaration of war would be handed to the British and French ambassadors in Rome at 1630 hours, local time. When Ciano presented the declaration, the French ambassador,

On 10 June, Ciano informed his ambassadors in London and Paris that a declaration of war would be handed to the British and French ambassadors in Rome at 1630 hours, local time. When Ciano presented the declaration, the French ambassador, Andr├® Fran├¦ois-Poncet

Andr├® Fran├¦ois-Poncet (13 June 1887 ŌĆō 8 January 1978) was a French politician and diplomat whose post as ambassador to Germany allowed him to witness first-hand the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, and the Nazi regime's ...

, was alarmed, while his British counterpart Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 ŌĆō 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from ...

, who received it at 1645 hours, "did not bat an eyelid", as Ciano recorded in his diary. The declaration of war took effect at midnight ( UTC+01:00) on 10/11 June. Italy's other embassies were informed of the declaration shortly before midnight. Commenting on the declaration of war, Fran├¦ois-Poncet called it "a dagger blow to man who has already fallen", and this occasioned United States President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's famous remark that "the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor". Fran├¦ois-Poncet and the French military attach├® in Rome, General Henri Parisot Henri Parisot (1881ŌĆō1963) was a French general during the First World War (1914ŌĆō18) and Second World War (1939ŌĆō45).

Parisot fought with the infantry during the First World War. In February 1918, he was appointed attach├® to the Italian gene ...

, declared that France would not fight a "rushed war" (''guerre brusqu├®e''), meaning that no offensive against Italy was being contemplated with France's dwindling military resources.

Late in the day, Mussolini addressed a crowd from the Palazzo Venezia

The Palazzo Venezia or Palazzo Barbo (), formerly Palace of St. Mark, is a palazzo (palace) in central Rome, Italy, just north of the Capitoline Hill. The original structure of this great architectural complex consisted of a modest medieval h ...

, in Rome. He declared that he had taken the country to war to rectify maritime frontiers. Mussolini's exact reason for entering the war has been much debated, although the consensus of historians is that it was opportunistic and imperialistic.

French response

On 26 May GeneralRen├® Olry

Ren├®-Henri Olry

CLH (28 June 1880 ŌĆō 3 January 1944) was a French general and commander of the Army of the Alps (french: l'Arm├®e des Alpes) during the Battle of France of World War II.

Biography Early life

Olry was born on 28 June 1880 in ...

had informed the prefect of the town of Menton, the largest on the Franco-Italian border, that the town would be evacuated at night on his order. He gave the order on 3 June and the following two nights the town was evacuated under the code name "Ex├®cutez Mandrin". On the evening of 10/11 June, after the declaration of war, the French were ordered from their ''casern

A casern, also spelled cazern or caserne, is a military barracks in a garrison town.Les gens de guerre ├Ā Saint-Julien-du-Sault, J Cr├®d├®, Imprimerie Fostier, 1976 In French-speaking countries, a ''caserne de pompier'' is a fire station.

In f ...

es'' to their defensive positions. French engineers destroyed the transportation and communication links across the border with Italy using fifty-three tons of explosives. For the remainder of the short war with Italy, the French took no offensive action.

As early as 14 May, the French Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministr ...

had given orders to arrest Italian citizens known or suspected of being anti-French in the event of war. Immediately after the declaration of war, the French authorities put up posters in all the towns near the Italian border ordering all Italian citizens to report to the local police by 15 June. Those who reported were asked to sign a declaration of loyalty that entailed possible future military service. The response was impressive: a majority of Italians reported, and almost all willingly signed the declaration. In Nice, over 5,000 Italians reported within three days.

Forces

French

In June 1940, only five Alpine passes between France and Italy were practicable for motor vehicles: the Little Saint Bernard Pass, the

In June 1940, only five Alpine passes between France and Italy were practicable for motor vehicles: the Little Saint Bernard Pass, the Mont Cenis

Mont Cenis ( it, Moncenisio) is a massif (el. 3,612 m / 11,850 ft at Pointe de Ronce) and a pass (el. 2,085 m / 6,840 ft) in Savoie (France), which forms the limit between the Cottian and Graian Alps.

Route

The term "Mont Cenis" cou ...

, the Col de Montgen├©vre

The Col de Montgen├©vre (; elevation 1860 m.) is a high mountain pass in the Cottian Alps, in France 2 kilometres away from Italy.

Description

The pass takes its name from the village Montgen├©vre (Hautes-Alpes), which lies in the vicinity ...

, the Maddalena Pass

The Maddalena Pass (Italian: ''Colle della Maddalena'' French: ''Col de Larche'', historically ''Col de l'Argenti├©re'') (elevation 1996 m.) is a high mountain pass between the Cottian Alps and the Maritime Alps, located on the border between I ...

(Col de Larche) and the Col de Tende

Col de Tende ( it, Colle di Tenda; elevation 1870 m) is a high mountain pass in the Alps, close to the border between France and Italy, although the highest section of the pass is wholly within France.

It separates the Maritime Alps from the Lig ...

. The only other routes were the coast road and mule trails. Prior to September 1939, the Alpine front was defended by the Sixth Army (General Antoine Besson) with eleven divisions and 550,000 men; ample to defend a well-fortified frontier. In October the Sixth Army was reduced to the level of an army detachment (''d├®tachement d'arm├®e''), renamed the Army of the Alps

The Army of the Alps (''Arm├®e des Alpes'') was one of the French Revolutionary armies. It existed from 1792ŌĆō1797 and from July to August 1799, and the name was also used on and off until 1939 for France's army on its border with Italy.

1792ŌĆ ...

(''Arm├®e des Alpes'') and placed under the command of General Ren├® Olry. A plan for a "general offensive on the Alpine front" (''offensive d'ensemble sur le front des Alpes''), in the event of war with Italy, had been worked out in August 1938 at the insistence of Generals Gaston Billotte

Gaston-Henri Billotte (10 February 1875 ŌĆō 23 May 1940) was a French military officer, remembered chiefly for his central role in the failure of the French Army to defeat the German invasion of France in May 1940. He was killed in a car accident ...

and Maurice Gamelin; the army was deployed for offensive operations in September 1939. Olry was ordered not to engage Italian military forces unless fired upon.

By December 1939, all mobile troops had been stripped from the ''Arm├®e des Alpes'', moved north to the main front against Germany, and his general staff much reduced. Olry was left with three Alpine divisions, some Alpine battalions, the Alpine fortress demibrigades, and two Alpine ''chasseur

''Chasseur'' ( , ), a French term for "hunter", is the designation given to certain regiments of French and Belgian light infantry () or light cavalry () to denote troops trained for rapid action.

History

This branch of the French Army orig ...

s'' demibrigades with 175,000ŌĆō185,000 men. Only 85,000 men were based on the frontier: 81,000 in 46 battalions faced Italy, supported by 65 groups of artillery and 4,500 faced Switzerland, supported by three groups of artillery. Olry also had series-B reserve divisions: second-line troops, typically comprising reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person is ...

s in their forties. Series-B divisions were a low priority for new equipment and the quality of training was mediocre. The ''Arm├®e des Alpes'' had 86 ''sections d'├®claireurs-skieurs'' (SES), platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two or more squads, sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the branch, but a platoon can be composed of 50 people, although specific platoons may rang ...

s of 35 to 40 men. These were elite troops trained and equipped for mountain warfare

Mountain warfare (also known as alpine warfare) is warfare in mountains or similarly rough terrain. Mountain ranges are of strategic importance since they often act as a natural border, and may also be the origin of a water source (for example, ...

, skiing and mountain climbing.

On 31 May, the Anglo-French Supreme War Council came to the decision that, if Italy joined the war, aerial attacks should commence against industrial and oil-related targets in northern Italy. The Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) was promised the use of two airfields, north of Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rh├┤ne and capital of the Provence-Alpes-C├┤te d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

as advanced bases for bombers flying from the United Kingdom. The headquarters of No. 71 Wing arrived at Marseille on 3 June as Haddock Force

Haddock Force was the name given to a number of Royal Air Force bombers dispatched to airfields in southern France to bomb northern Italian industrial targets, once Italy declared war, which was thought to be imminent. Italy entered the Second Worl ...

. It comprised Whitley and Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

bombers from No. 10, 51, 58, 77, 102 102 may refer to:

*102 (number), the number

* AD 102, a year in the 2nd century AD

*102 BC, a year in the 2nd century BC

* 102 (ambulance service), an emergency medical transport service in Uttar Pradesh, India

* 102 (Clyde) Field Squadron, Royal En ...

and 149 Squadrons. The French held back part of the ''Arm├®e de l'Air

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: Arm├®e de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Ar ...

'' in case Italy entered the war, as Aerial Operations Zone of the Alps (''Zone d'Op├®rations A├®riennes des Alpes'', ZOAA), with its headquarters at Valence-Chabeuil. Italian army intelligence, the '' Servizio Informazioni Militari'' (SIM), overestimated the number of aircraft still available in the Alpine and Mediterranean theatres by 10 June, when many had been withdrawn to face the German invasion; ZOAA had 70 fighters, 40 bombers and 20 reconnaissance craft, with a further 28 bombers, 38 torpedo bombers and 14 fighters with '' A├®ronavale'' (naval aviation) and three fighters and 30 other aircraft on Corsica. Italian air reconnaissance had put the number of French aircraft at over 2,000 and that of the British at over 620, in the Mediterranean. SIM also estimated the strength of the ''Arm├®e des Alpes'' at twelve divisions, although at most it had six by June.

Order of battle

''Arm├®e des Alpes'', 10 May: :Fortified Sector under the Army: General Ren├® Magnien :: Defensive Sector of the Rh├┤ne :14th Corps: General ├ētienne Beynet ::Corps troops ::64th Mountain Infantry Division ::66th Mountain Infantry Division ::Fortified Sector of Savoy :: Fortified Sector of the Dauphin├® :15th Corps: General Alfred Montagne ::Corps troops ::2nd Colonial Infantry Division ::65th Mountain Infantry Division ::Fortified Sector of Alpes-MaritimesFortifications

Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the Minister of the Armed Forces (France), French Minister of War Andr├® Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, F ...

ŌĆöalong their border with Germany. This line had been designed to deter a German invasion across the Franco-German border and funnel an attack into Belgium, which could then be met by the best divisions of the French Army. Thus, any future war would take place outside of French territory avoiding a repeat of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

In addition to this force, the French had constructed a series of fortifications known as Alpine Line

The Alpine Line (french: Ligne Alpine) or Little Maginot Line (French: ''Petite Ligne Maginot'') was the component of the Maginot Line that defended the southeastern portion of France. In contrast to the main line in the northeastern portion of Fra ...

, or the Little Maginot Line. In contrast to the Maginot Line facing the German border, the fortifications in the Alps were not a continuous chain of forts. In the Fortified Sector of the Dauphin├®, several passes allowed access through the Alps between Italy and France. To defend these passes, the French had constructed nine artillery and ten infantry bunker

A bunker is a defensive military fortification designed to protect people and valued materials from falling bombs, artillery, or other attacks. Bunkers are almost always underground, in contrast to blockhouses which are mostly above ground. T ...

s. In the Fortified Sector of the Maritime Alps, the terrain was less rugged and presented the best possible invasion route for the Italians. In this area, long between the coast and the more impenetrable mountains, the French constructed 13 artillery bunkers and 12 infantry forts. Along the border, in front of the above main fortifications, numerous blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

s and casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s had been constructed. However, by the outbreak of the war some of the Little Maginot Line's positions had yet to be completed and overall the fortifications were smaller and weaker than those in the main Maginot Line.

Italy had a series of fortifications along its entire land border: the Alpine Wall

The Alpine Wall (''Vallo Alpino'') was an Italian system of fortifications along the of Italy's northern frontier. Built in the years leading up to World War II at the direction of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, the defensive line faced Franc ...

(''Vallo Alpino''). By 1939 the section facing France, the Occidental Front, had 460 complete ''opere'' (works, like French ''ouvrages'') with 133 artillery pieces. As Mussolini prepared to enter the war, construction work continued round the clock on the entire wall, including the section fronting Germany. The Alpine Wall was garrisoned by the ''Guardia alla Frontiera

The Guardia alla Frontiera (GaF), was an Italian Army Border guard created in 1937 who defended the 1,851 km of northern Italian frontiers with the so-called "Vallo Alpino Occidentale" (487 km with France), "Vallo Alpino Settentrionale" ...

'' (GAF), and the Occidental Front was divided into ten sectors and one autonomous subsector. When Italy entered the war, sectors I and V were placed under the command of XV Army Corps, sectors II, III and IV under II Army Corps and sectors VI, VII, VIII, IX and X under I Army Corps.

Italian

Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manf ...

had formed 73 divisions out of this influx of men. However, only 19 of these divisions were complete and fully combat-ready. A further 32 were in various stages of being formed and could be used for combat if needed, while the rest were not ready for battle.

Italy was prepared, in the event of war, for a defensive stance on both the Italian and Yugoslav fronts, for defence against French aggression and for an offensive against Yugoslavia while France remained neutral. There was no planning for an offensive against France beyond mobilisation. On the French border, 300,000 menŌĆöin 18 infantry and four alpine divisionsŌĆöwere massed. These were deployed defensively, mainly at the entrance to the valleys and with their artillery arranged to hit targets inside the border in the event of an invasion. They were not prepared to assault French fortifications, and their deployment did not change prior to June 1940. These troops formed the 1st

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

and 4th armies, which were under the command of the Italian Crown Prince Umberto of Savoy of Army Group West (''Gruppo Armate Ovest''). The chief of staff of Army Group West was General Emilio Battisti. The 7th Army was held in reserve at Turin, and a further ten mobile divisions, the Army of the Po The Army of the Po (Italian ''Armata del Po''), numbered the Sixth Army (''6a Armata''), was a field army of the Royal Italian Army (''Regio Esercito'') during World War II (1939ŌĆō45).

History

When it was initially formed on 10 November 1938 und ...

(later Sixth Army), were made available. However, most of these latter divisions were still in the process of mobilizing and not yet ready for battle. Supporting Army Group West was 3,000 pieces of artillery and two independent armoured regiments. After the campaign opened, further tank support was provided by the 133rd Armoured Division Littorio bringing the total number of tanks deployed to around 200. The ''Littorio'' had received seventy of the new type M11/39 medium tanks shortly before the declaration of war.

Despite the numerical superiority, the Italian military was plagued by numerous issues. During the 1930s, the army had developed an operational doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

of rapid mobile advances backed by heavy artillery support. Starting in 1938, General Alberto Pariani

Alberto is the Romance version of the Latinized form (''Albertus'') of Germanic '' Albert''. It is used in Italian, Portuguese and Spanish. The diminutive forms are ''Albertito'' in Spain or ''Albertico'' in some parts of Latin America, Alber ...

initiated a series of reforms that radically altered the army. By 1940, all Italian divisions had been converted from triangular division A triangular division is a designation given to the way military divisions are organized. In a triangular organization, the division's main body is composed of three regimental maneuver elements. These regiments may be controlled by a brigade hea ...

s into binary divisions. Rather than having three infantry regiments, the divisions were composed of two, bringing their total strength to around 7,000 men and therefore smaller than their French counterparts. The number of artillery guns of the divisional artillery regiment had also been reduced. Pariani's reforms also promoted frontal assault

The military tactic of frontal assault is a direct, full-force attack on the front line of an enemy force, rather than to the flanks or rear of the enemy. It allows for a quick and decisive victory, but at the cost of subjecting the attackers to ...

s to the exclusion of other doctrines. Further, army front commanders were forbidden to communicate directly with their aeronautical and naval counterparts, rendering inter-service cooperation almost impossible.

Marshal

Marshal Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 ŌĆō 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

had complained that due to the lack of motor vehicles, the Italian army would be unable to undertake mobile warfare as had been envisaged let alone on the levels the German military was demonstrating. The issues also extended to the equipment used. Overall, the Italian troops were poorly equipped and such equipment was inferior to that in use by the French. After the invasion had begun, a circular advised that troops were to be billeted in private homes where possible because of a shortage of tent flies. The vast majority of Italy's tanks were L3/35

The L3/35 or Carro Veloce CV-35 was an Italian tankette that saw combat before and during World War II. Although designated a light tank by the Italian Army, its turretless configuration, weight and firepower make it closer to contemporary tan ...

tankette

A tankette is a tracked armoured fighting vehicle that resembles a small tank, roughly the size of a car. It is mainly intended for light infantry support and scouting.

s, mounting only a machine gun and protected by light armour unable to prevent machine gun rounds from penetrating. They were obsolete by 1940, and have been described by Italian historians as "useless". According to one study, 70% of engine failure was due to inadequate driver training. The same issue extended to the artillery arm. Only 246 pieces, out of the army's entire arsenal of 7,970 guns, were modern. The rest were up to forty years old and included many taken as reparations, in 1918, from the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

.

The ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was aboli ...

'' (Italian Air Force) had the third largest fleet of bombers in the world when it entered the war. A potent symbol of Fascist modernisation, it was the most prestigious of Italy's service branches, as well as the most recently battle-hardened, having participated in the Spanish Civil War. The 1a Squadra Aerea in northern Italy, the most powerful and well-equipped of Italy's ''squadre aeree'', was responsible for supporting operations on the Alpine front. Italian aerial defences were weak. As early as August 1939 Italy had requested from Germany 150 batteries of 88-mm anti-aircraft (AA) guns. The request was renewed in March 1940, but declined on 8 June. On 13 June, Mussolini offered to send one Italian armoured division to serve on the German front in France in exchange for 50 AA batteries. The offer was refused.

On 29 May, Mussolini convinced King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

, who was constitutionally the supreme commander of the Italian armed forces, to delegate his authority to Mussolini and on 4 June Badoglio was already referring to him as supreme commander. On 11 June the king issued a proclamation to all troops, naming Mussolini "supreme commander of the armed forces operating on all fronts". This was a mere proclamation and not a royal decree and lacked legal force. Technically, it also restricted Mussolini's command to forces in combat but this distinction was unworkable. On 4 June, Mussolini issued a charter sketching out a new responsibility for the Supreme General Staff (''Stato Maggiore Generale'', or ''Stamage'' for short): to transform his strategic directives into actual orders for the service chiefs. On 7 June ''Superesercito'' (the Italian army supreme command) ordered Army Group West to maintain "absolute defensive behaviour both on land and n the

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

air", casting in doubt Mussolini's comment to Badoglio about a few thousand dead. Two days later, the army general staff (''Stato Maggiore del Regio Esercito'') ordered the army group to strengthen its anti-tank defences. No attack was planned or ordered for the following day when the declaration of war would be issued.

Order of battle

Army Group West:*

1st Army First Army may refer to:

China

* New 1st Army, Republic of China

* First Field Army, a Communist Party of China unit in the Chinese Civil War

* 1st Group Army, People's Republic of China

Germany

* 1st Army (German Empire), a World War I field Arm ...

, General Pietro Pintor (Chief of Staff: General Fernando Gelich)

** II Army Corps, General Francesco Bettini

*** 4th Alpine Division "Cuneense"

The 4th Alpine Division "Cuneense" ( it, 4ª Divisione alpina "Cuneense") was a Division (military), division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II, which specialized in mountain warfare. The headquarters of the division was in the city of ...

*** 4th Infantry Division "Livorno"

The 4th Infantry Division "Livorno" ( it, 4ª Divisione di fanteria "Livorno") was a infantry division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Livorno was classified as a mountain infantry division, which meant that the division's arti ...

*** 33rd Infantry Division "Acqui"

The 33rd Infantry Division "Acqui" ( it, 33ª Divisione di fanteria "Acqui") was an infantry Division (military), division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Acqui was classified as a mountain infantry division, which meant that ...

*** 36th Infantry Division "Forlì"

** III Army Corps, General Mario Arisio

*** 3rd Infantry Division "Ravenna"

*** 6th Infantry Division "Cuneo"

*** 1st Alpine Group (three Alpini

The Alpini are the Italian Army's specialist mountain infantry. Part of the army's infantry corps, the speciality distinguished itself in combat during World War I and World War II. Currently the active Alpini units are organized in two operat ...

battalions and two mountain artillery groups)

** XV Army Corps, General Gastone Gambara

Gastone Gambara (10 November 1890 ŌĆō 27 February 1962) was an Italian General who participated in World War I and World War II. He excelled during the Italian intervention in favor of the nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. During World War ...

(recalled from his ambassadorial post in Madrid on 10 May)

*** 5th Infantry Division "Cosseria"

*** 37th Infantry Division "Modena"

*** 44th Infantry Division "Cremona"

*** 2nd Alpine Group (four Alpini battalions, one Blackshirt

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Nation ...

battalion, two mountain artillery groups)

** Army Reserve

*** 7th Infantry Division "Lupi di Toscana"

*** 16th Infantry Division "Pistoia"

*** 22nd Infantry Division "Cacciatori delle Alpi"

The 22nd Infantry Division "Cacciatori delle Alpi" ( it, 22ª Divisione di fanteria "Cacciatori delle Alpi" English: Hunters of the Alps) was an infantry division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The division was based in Perugi ...

*** 5th Alpine Division "Pusteria"

*** 1st Bersaglieri Regiment

The 1st Bersaglieri Regiment ( it, 1┬░ Reggimento Bersaglieri) is an active unit of the Italian Army based in Cosenza in the Calabria region. The regiment is part of the Italian infantry corps' Bersaglieri speciality and operationally assigned to ...

*** 3rd Tank Infantry Regiment

*** Regiment "Cavalleggeri di Monferrato"

* 4th Army, General Alfredo Guzzoni

Alfredo Guzzoni (12 April 1877 ŌĆō 15 April 1965) was an Italian military officer who served in both World War I and World War II.

Early life

Guzzoni was a native of Mantua, Italy.

Italian Army

Guzzoni joined the Italian Royal Army ('' Regio Es ...

(Chief of Staff: General Mario Soldarelli

Mario Soldarelli ( Florence, 21 January 1886 – Rome, 27 April 1962) was an Italian general during World War II.

Biography

He was born in Florence on January 21, 1886, and entered the Royal Military Academy of Artillery and Engineers of ...

)

** I Army Corps, General Carlo Vecchiarelli

Carlo Vecchiarelli (10 January 1884 ŌĆō 13 December 1948) was an Italian general. He was a veteran combatant of the First World War. Between the two world wars he held the positions of Military Attach├® at the Italian Embassy in Prague, Honora ...

*** 1st Infantry Division "Superga"

*** 24th Infantry Division "Pinerolo"

*** 59th Infantry Division "Cagliari"

** IV Army Corps, General Camillo Mercalli

Camillo Mercalli ( Savona, 18 July 1882 – Turin, 13 November 1974) was an Italian general during World War II.

Biography

He was born in Savona on 18 July 1882, the son of Antonio Mercalli and Gabriella Marchesi Massimino, and after enl ...

*** 2nd Infantry Division "Sforzesca"

The 2nd Infantry Division "Sforzesca" ( it, 2ª Divisione di fanteria "Sforzesca") was a infantry Division (military), division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Sforzesca was classified as a mountain infantry division, which mean ...

*** 26th Infantry Division "Assietta"

** Alpine Army Corps

The Comando Truppe Alpine (Alpine Troops Command) or COMTA (formerly also COMALP) commands the Mountain Troops of the Italian Army, called ''Alpini'' (singular: ''Alpino'') and various support and training units. It is the successor to the ''4┬║ ...

, General Luigi Negri

*** 1st Alpine Division "Taurinense"

*** 3rd Alpini Regiment

The 3rd Alpini Regiment ( it, 3┬░ Reggimento Alpini) is a regiment of the Italian Army's mountain infantry speciality, the Alpini, which distinguished itself in combat during World War I and World War II. The regiment is based in Pinerolo and as ...

*** Autonomous Group "Levanna" (three Alpini battalions, and one mountain artillery group)

** Army Reserve

*** 2nd Alpine Division "Tridentina"

The 2nd Alpine Division "Tridentina" ( it, 2ª Divisione alpina "Tridentina") was a Division (military), division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II, which specialized in mountain warfare. The Alpini that formed the divisions are a hig ...

*** 11th Infantry Division "Brennero"

*** 58th Infantry Division "Legnano"

The 58th Infantry Division "Legnano" ( it, 58ª Divisione di fanteria "Legnano") was an infantry division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Legnano's predecessor division was formed on 8 February 1934 in Milan and named for the ...

*** 1st Tank Infantry Regiment

*** Regiment "Nizza Cavalleria"

*** 4th Bersaglieri Regiment

Battle

Marshal Graziani, as army chief of staff, went to the front to take over the general direction of the war after 10 June. He was joined by the under-secretary of war, General

Marshal Graziani, as army chief of staff, went to the front to take over the general direction of the war after 10 June. He was joined by the under-secretary of war, General Ubaldo Soddu

Ubaldo Soddu (23 July 1883 ŌĆō 25 July 1949) was an Italian military officer, who commanded the Italian Forces in the Greco-Italian War for a month.

Soddu was born in Salerno. From 1939 to 1940, Soddu was under-secretary at the Ministry of War. ...

, who had no operational command, but who served as Mussolini's connection to the front and was appointed deputy chief of the Supreme General Staff on 13 June. Graziani's adjutant, General Mario Roatta

Mario Roatta (2 February 1887 ŌĆō 7 January 1968) was an Italian general. After serving in World War I he rose to command the Corpo Truppe Volontarie which assisted Francisco Franco's force during the Spanish Civil War. He was the Deputy Chief o ...

, remained in Rome to transmit the orders of MussoliniŌĆörestrained somewhat by Marshal BadoglioŌĆöto the front. Many of Roatta's orders, like "be on the heels of the enemy; audacious; daring; rushing after", were quickly contradicted by Graziani. Graziani kept all the minutes of his staff meeting during June 1940, in order to absolve himself and condemn both subordinates and superiors should the offensive fail, as he expected it would.

Air campaign

In the first air raids of Italy's war,Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 ''Sparviero'' (Italian for sparrowhawk) was a three-engined Italian medium bomber developed and manufactured by aviation company Savoia-Marchetti. It may be the best-known Italian aeroplane of the Second World War. ...

s from the 2a Squadra Aerea (Sicily and Pantelleria) under fighter escort twice struck Malta on 11 June, beginning the siege of Malta that lasted until November 1942. The first strike that morning involved 55 bombers, but Malta's anti-aircraft defences reported an attack of between five and twenty aircraft, suggesting that most bombers failed to find their target. The afternoon strike involved 38 aircraft. On 12 June some SM.79s from Sardinia attacked French targets in northern Tunisia and, on 13 June 33 SM.79s of the 2a Squadra Aerea bombed the Tunisian aerodromes. That day Fiat BR.20

The Fiat BR.20 ''Cicogna'' (Italian: "stork") was a low-wing twin-engine medium bomber that was developed and manufactured by Italian aircraft company Fiat. It holds the distinction of being the first all-metal Italian bomber to enter service;Big ...

s and CR.42s of the 1a Squadra Aerea in northern Italy made the first attacks on metropolitan France, bombing the airfields of the ZOAA, while the 3a Squadra Aerea in central Italy targeted shipping of France's Mediterranean coast.

Immediately after the declaration of war, Haddock Force began to prepare for a bombing run. The French, in order to prevent retaliatory Italian raids, blocked the runways and prevented the Wellingtons from taking off. This did not deter the British. On the night of 11 June, 36 RAF Whitleys took off from bases in Yorkshire