Irvingite on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in

The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. 2007. The tradition to which the Catholic Apostolic Church belongs is referred to as Irvingism or the Irvingian movement after

In the 21st century, of the principal CAC buildings in London, the Catholic Apostolic cathedral, in Gordon Square, survives and has been let for other religious purposes.

In the 21st century, of the principal CAC buildings in London, the Catholic Apostolic cathedral, in Gordon Square, survives and has been let for other religious purposes.

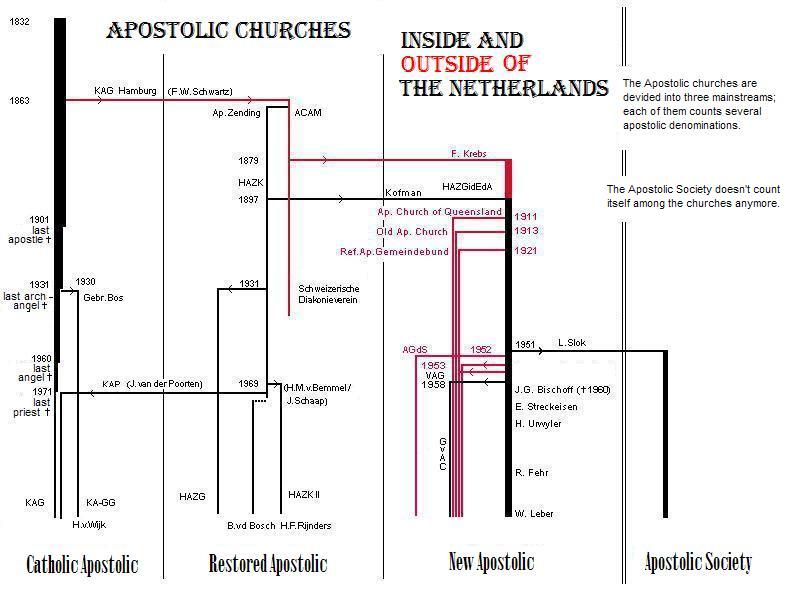

After the death of three apostles in 1855 the apostolate declared that there was no reason to call new apostles. Two callings of substitutes were explained by the apostolate in 1860 as coadjutors to the remaining apostles. After this event another apostle was called in Germany in 1862 by the prophet Heinrich Geyer. The Apostles did not agree with this calling, and therefore the larger part of the

After the death of three apostles in 1855 the apostolate declared that there was no reason to call new apostles. Two callings of substitutes were explained by the apostolate in 1860 as coadjutors to the remaining apostles. After this event another apostle was called in Germany in 1862 by the prophet Heinrich Geyer. The Apostles did not agree with this calling, and therefore the larger part of the

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

around 1831 and later spread to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

."Catholic Apostolic Church"The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. 2007. The tradition to which the Catholic Apostolic Church belongs is referred to as Irvingism or the Irvingian movement after

Edward Irving

Edward Irving (4 August 17927 December 1834) was a Scottish clergyman, generally regarded as the main figure behind the foundation of the Catholic Apostolic Church.

Early life

Edward Irving was born at Annan, Annandale the second son of Ga ...

(1792–1834), a clergyman of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

credited with organising the movement.

The church was organised in 1835 with the fourfold ministry of "apostles, prophets, evangelists, and pastors".

As a result of schism within the Catholic Apostolic Church, other Irvingian Christian denominations emerged, including the Old Apostolic Church

The Old Apostolic Church (OAC) is a church with roots in the Catholic Apostolic Church.

History

The Old Apostolic Church's roots are found in the Catholic Apostolic Church that was established in 1832 as an outflow of the Albury Movement.

Establ ...

, New Apostolic Church, Reformed Old Apostolic Church

The Reformed Old Apostolic Church is a chiliastic religion with roots in the Catholic Apostolic Church and the Old Apostolic Church. It is part of a branch in Christianity called Irvingismhttp://ebasic.easily.co.uk/030046/04C059/7%20Testification% ...

and United Apostolic Church

The member churches of the United Apostolic Church are independent communities in the tradition of the catholic apostolic revival movement.

Further reading

* Apostolic Church of Queensland, ''Book of faith''

* Wissen, Volker: Zur Freiheit berufe ...

; of these, the New Apostolic Church is the largest Irvingian Christian denomination today, with 16 million members.

Irvingism teaches three sacraments: Baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

, Holy Communion and Holy Sealing.

History

Edward Irving

Edward Irving

Edward Irving (4 August 17927 December 1834) was a Scottish clergyman, generally regarded as the main figure behind the foundation of the Catholic Apostolic Church.

Early life

Edward Irving was born at Annan, Annandale the second son of Ga ...

, also a minister in the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

, preached in his church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

at Regent Square in London on the speedy return of Jesus Christ and the real substance of his human nature.

Irving's relationship to this community was, according to its members, somewhat similar to that of John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

to the early Christian Church

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

. He was the forerunner and prophet of the coming dispensation, not the founder of a new sect; and indeed the only connexion which Irving seems to have had with the Catholic Apostolic Church was in fostering spiritual persons who had been driven out of other congregations for the exercise of their spiritual gifts

A spiritual gift or charism (plural: charisms or charismata; in Greek singular: χάρισμα

''charisma'', plural: χαρίσματα ''charismata'') is an extraordinary power given by the Holy Spirit."Spiritual gifts". ''A Dictionary of the ...

.

Around him, as well as around other congregations of different origins, coalesced persons who had been driven out of other churches, wanting to "exercise their spiritual gifts". Shortly after Irving's trial and deposition (1831), he restarted meetings in a hired hall in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, and much of his original congregation

A congregation is a large gathering of people, often for the purpose of worship.

Congregation may also refer to:

* Church (congregation), a Christian organization meeting in a particular place for worship

*Congregation (Roman Curia), an administr ...

followed him. Having been expelled from the Church of Scotland, Irving took to preaching in the open air in Islington, until a new church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

was built for him and his followers in Duncan Street, Islington, funded by Duncan Mackenzie

Duncan Mackenzie (17 May 1861 – 1934) was a Scottish archaeologist, whose work focused on one of the more spectacular 20th century archaeological finds, Crete's palace of Knossos, the proven centre of Minoan civilisation.

Early biography

D ...

of Barnsbury

Barnsbury is an area of north London in the London Borough of Islington, within the N1 and N7 postal districts.

The name is a syncopated form of ''Bernersbury'' (1274), being so called after the Berners family: powerful medieval manorial ...

, a former elder of Irving's London church.

Shortly after Irving's trial and deposition (1831), certain persons were, at some meetings held for prayer, designated as “called to be apostles of the Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

” by certain others claiming prophetic gifts.

Naming of the apostles

In the year 1835, six months after Irving's death, six other people were similarly designated as “called” to complete the number of the “twelve,” who were then formally “separated,” by thepastors

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and An ...

of the local congregations to which they belonged, to their higher office in the universal church on the 14th of July 1835. This separation is understood by the community not as “in any sense being a schism or separation from the one Catholic Church, but a separation to a special work of blessing and intercession on behalf of it.” The twelve were afterwards guided to ordain others—twelve prophets, twelve evangelists, and twelve pastors, “sharing equally with them the one Catholic Episcopate,” and also seven deacons for administering the temporal affairs of the church catholic.

The names of those twelve apostles were: John Bate Cardale John Bate Cardale (1802–1877) was an English religious leader, the first apostle of the Catholic Apostolic Church.

Life

J. B. Cardale was born in London on 7 November 1802, as the eldest of five children to William Cardale (1775-1838) and Mary An ...

, Henry Drummond, Henry King-Church, Spencer Perceval

Spencer Perceval (1 November 1762 – 11 May 1812) was a British statesman and barrister who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1809 until his assassination in May 1812. Perceval is the only British prime minister to ...

, Nicholas Armstrong, Francis Woodhouse (Francis Valentine Woodhouse), Henry Dalton, John Tudor (John O. Tudor), Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, Francis Sitwell, William Dow and Duncan Mackenzie

Duncan Mackenzie (17 May 1861 – 1934) was a Scottish archaeologist, whose work focused on one of the more spectacular 20th century archaeological finds, Crete's palace of Knossos, the proven centre of Minoan civilisation.

Early biography

D ...

.

Structure and ministries

Eachcongregation

A congregation is a large gathering of people, often for the purpose of worship.

Congregation may also refer to:

* Church (congregation), a Christian organization meeting in a particular place for worship

*Congregation (Roman Curia), an administr ...

was presided over by its “angel” or bishop (who ranks as angel-pastor in the Universal Church); under him are four-and-twenty priests, divided into the four ministries of “elders, prophets, evangelists and pastors,” and with these are the deacons, seven of whom regulate the temporal affairs of the church—besides whom there are also “sub-deacons, acolytes, singers, and door-keepers.” The understanding is that each elder, with his co-presbyters and deacons, shall have charge of 500 adult communicants in his district; but this has been but partially carried into practice. This is the full constitution of each particular church or congregation as founded by the “restored apostles,” each local church thus “reflecting in its government the government of the church catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

by the angel or high priest Jesus Christ, and His forty-eight presbyters in their fourfold ministry (in which apostles and elders always rank first), and under these the deacons of the church catholic.”

The priesthood is supported by tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

; it being deemed a duty on the part of all members of the church who receive yearly incomes to offer a tithe of their increase every week, besides the free-will offering for the support of the place of worship, and for the relief of distress. Each local church sends “a tithe of its tithes” to the “Temple,” by which the ministers of the Universal Church are supported and its administrative expenses defrayed; by these offerings, too, the needs of poorer churches are supplied.

Liturgy and forms of worship

Sources of forms of worship

For the service of the church a comprehensive book of liturgies and offices was provided by the "apostles." It dates from 1842 and is based on the Anglican, Roman and Greek liturgies. Lights,incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also b ...

, vestments, holy water

Holy water is water that has been blessed by a member of the clergy or a religious figure, or derived from a well or spring considered holy. The use for cleansing prior to a baptism and spiritual cleansing is common in several religions, from ...

, chrism

Chrism, also called myrrh, ''myron'', holy anointing oil, and consecrated oil, is a consecrated oil used in the Anglican, Assyrian, Catholic, Nordic Lutheran, Old Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Latter Day Saint churches in th ...

, and other adjuncts of worship are in constant use. In 1911, the ceremonial in its completeness could be seen in the church in Gordon Square, London and elsewhere.

The daily worship consists of "matins

Matins (also Mattins) is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning.

The earliest use of the term was in reference to the canonical hour, also called the vigil, which was originally celebrated b ...

" with "proposition" (or exposition) of the sacrament at 6 a.m., prayers at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m., and "vespers

Vespers is a service of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic (both Latin and Eastern), Lutheran, and Anglican liturgies. The word for this fixed prayer time comes from the Latin , meanin ...

" with "proposition" at 5 p.m. On all Sundays and holy days there is a “solemn celebration of the eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

” at the high altar; on Sundays this is at 10 a.m. On other days " low celebrations" are held in the side-chapels, which with the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ov ...

in all churches correctly built after apostolic directions are separated or marked off from the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

by open screens with gates. The community has always laid great stress on symbolism, and in the eucharist, while rejecting both transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις '' metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of ...

and consubstantiation, holds strongly to a real (mystical) presence. It emphasizes also the "phenomena" of Christian experience and deems miracle and mystery to be of the essence of a spirit-filled church.

The services were published as ''The Liturgy and other Divine Offices of the Church''. Apostle Cardale put together two large volumes of writings about the liturgy, with references to its history and the reasons for operating in the ways defined, which was published under the title ''Readings on the Liturgy''.

The Eucharist, being the memorial sacrifice of Christ, is the central service. The Irvingian Churches teach the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, though they rejected what they saw as the philosophical explanations of the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation as well as Lollardist

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Cathol ...

doctrine of consubstantiation.

Some of the music in the Catholic Apostolic Church is composed by Edmund Hart Turpin

Edmund Hart Turpin (4 May 1835, Nottingham – 25 October 1907, Middlesex) was an organist, composer, writer and choir leader based in Nottingham and London.

Life

Edmund Hart Turpin was born into a musical family that ran a dealership in musica ...

, former secretary of the Royal College of Organists

The Royal College of Organists (RCO) is a charity and membership organisation based in the United Kingdom, with members worldwide. Its role is to promote and advance organ playing and choral music, and it offers music education, training and de ...

.

Special services

Sacraments

Irvingism teaches three sacraments:Baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

, Holy Communion and Holy Sealing.

Prophecy and spiritual gifts

Number of congregations and members

In 1911, the CAC claimed to have among its clergy many of the Roman, Anglican and other churches, the orders of those ordained by Greek, Roman and Anglican bishops being recognized by it with the simple confirmation of an "apostolic act." The community had not changed in 1911 in general constitution or doctrine. At the time, it did not publish statistics, and its growth during late years before 1911 is said to have been more marked in theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and in certain European countries

The list below includes all entities falling even partially under any of the regions of Europe, various common definitions of Europe, geographical or political. Fifty generally recognised sovereign states, Kosovo with limited, but substantial, ...

, such as Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, than in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

. There are nine congregations enumerated in ''The Religious Life of London'' (1904). In the 21st century, of the principal CAC buildings in London, the Catholic Apostolic cathedral, in Gordon Square, survives and has been let for other religious purposes.

In the 21st century, of the principal CAC buildings in London, the Catholic Apostolic cathedral, in Gordon Square, survives and has been let for other religious purposes.

Notable members

Aside from Irving, notable members includeThomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, Baron Carlyle of Torthorwald (1803–1855), who was given responsibility for northern Germany. (This is not Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

the essayist (1795–1881), although Irving knew both men.). Besides Thomas Carlyle, Edward Wilton Eddis

Edward Wilton Eddis (* 10 May 1825, Islington; † 18 October 1905, Toronto) was a poet and prophet in the Catholic Apostolic Church at Westminster, London and co-author of the ''Hymns for the Use of the Churches'', the hymnal of the Catholic Apo ...

contributed to the Catholic Apostolic Hymnal; Edmund Hart Turpin

Edmund Hart Turpin (4 May 1835, Nottingham – 25 October 1907, Middlesex) was an organist, composer, writer and choir leader based in Nottingham and London.

Life

Edmund Hart Turpin was born into a musical family that ran a dealership in musica ...

contributed much to CAC music.

New Apostolic Church

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

congregation who followed F .W. Schwartz, excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. Out of this, sprang the ''Allgemeine Christliche Apostolische Mission'' (ACAM) in 1863 and the Dutch branch of the Restored Apostolic Mission Church (at first known as ''Apostolische Zending'', since 1893 officially registered as Hersteld Apostolische Zendingkerk

The Restored Apostolic Mission Church (Hersteld Apostolische Zendingkerk - HAZK) was a Bible-believing, chiliastic church society in the Netherlands, Germany, South Africa and Australia. It came forth from the Catholic Apostolic Congregation at ...

(HAZK)). This later became the New Apostolic Church.

Notable buildings

* The Church of Christ the King, Bloomsbury in Gordon Square, London: a massive Early-English neo-Gothic building constructed 1850–1854, designed byRaphael Brandon

John Raphael Rodrigues Brandon (5 April 1817 in London – 8 October 1877 at his chambers at 17 Clement's Inn, Strand, London) was a British architect and architectural writer.

Life

Training

He was the second child of the six children of ...

.

* The Apostles' Chapel at Albury, Surrey

Albury is a village and civil parish in the borough of Guildford in Surrey, England, about south-east of Guildford town centre. The village is within the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Farley Green, Little London and adjace ...

: a Gothic Revival building in 15th century Gothic style, completed in 1840, designed by William MacIntosh Brookes.

* Maida Avenue, Paddington, London: built 1891–1894, designed by John Loughborough Pearson

John Loughborough Pearson (5 July 1817 – 11 December 1897) was a British Gothic Revival architect renowned for his work on churches and cathedrals. Pearson revived and practised largely the art of vaulting, and acquired in it a proficiency ...

.

* Mansfield Place Church, Edinburgh: a Scottish neo-Romanseque building completed in 1885, designed by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson

Sir Robert Rowand Anderson, (5 April 1834 – 1 June 1921) was a Scottish Victorian architect. Anderson trained in the office of George Gilbert Scott in London before setting up his own practice in Edinburgh in 1860. During the 1860s his ...

.

Shortage of holy order

All ministers in the church wereordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

by an apostle, or under delegated authority of an apostle. Thus, following the death of the last of the apostles, Francis Valentine Woodhouse, in 1901, the consensus of trustees, who administer the remaining assets, has been that no further ordinations are possible.

Archives

A collection of papers related to the Catholic Apostolic Church, compiled by the Cousland family of Glasgow, is held at the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham.See also

*Apostolic Church of Queensland

The Apostolic Church of Queensland is an Australian Christian denomination. It was founded in Queensland, Australia, by H. F. Niemeyer and took its current name in 1911.

The church's logo is a 4R-symbol. The four "R"s stand for: RIGHT - ROYAL ...

, an Australian religious denomation established by H. F. Niemeyer in 1883

References

*Further reading

* . * . * . * . * , (Vol. II). * . * . * .Doctrine

* . * . * . * . * Francis Sitwell ''The Purpose of God in Creation and Redemption'' (6th ed., 1888)External links

* {{Scottish religion Religious organizations established in 1835 1831 establishments in England Adventism Restorationism (Christianity)