On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized

Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

college students belonging to the

Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dyna ...

, took over the

U.S. Embassy in

Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and took them as hostages. A diplomatic standoff ensued. The hostages were held for 444 days, being released on January 20, 1981.

Western media described the crisis as an "entanglement" of "vengeance and mutual incomprehension."

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

called the hostage-taking an act of "blackmail" and the hostages "victims of terrorism and anarchy."

In Iran, it was widely seen as an act against the U.S. and its influence in Iran, including its perceived attempts to undermine the Iranian Revolution and its

longstanding support of the shah of Iran,

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 Octob ...

, who was overthrown in 1979.

After Shah Pahlavi was overthrown, he was admitted to the U.S. for cancer treatment. Iran demanded his return in order to stand trial for crimes that he was accused of committing during his reign. Specifically, he was accused of committing crimes against Iranian citizens with the help of

his secret police. Iran's demands were rejected by the United States, and Iran saw the decision to grant him asylum as American complicity in those atrocities. The Americans saw the hostage-taking as an egregious violation of the principles of international law, such as the

Vienna Convention, which granted

diplomats immunity from arrest and made diplomatic compounds inviolable. The Shah left the United States in December 1979 and was ultimately granted asylum in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, where he died from complications of cancer at age 60 on July 27, 1980.

Six American diplomats who had evaded capture were rescued by a

joint CIA–Canadian effort on January 27, 1980. The crisis reached a climax in early 1980 after

diplomatic negotiations

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

failed to win the release of the hostages. Carter ordered the U.S. military to attempt a rescue mission –

Operation Eagle Claw – using warships that included and , which were patrolling the waters near Iran. The failed attempt on April 24, 1980, resulted in the death of one Iranian civilian and the accidental deaths of eight American servicemen after one of the helicopters crashed into a transport aircraft. U.S. Secretary of State

Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance Sr. (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary o ...

resigned his position following the failure. In September 1980,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

invaded Iran, beginning the

Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Counci ...

. These events led the Iranian government to enter negotiations with the U.S., with

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

acting as a mediator. The crisis is considered a pivotal episode in the history of

Iran–United States relations

Iran and the United States have had no formal diplomatic relations since April 7, 1980. Instead, Pakistan serves as Iran's protecting power in the United States, while Switzerland serves as the United States' protecting power in Iran. Contacts are ...

.

Political analysts cited the standoff as a major factor in the continuing downfall of

Carter's presidency

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the 39th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. A Democrat from Georgia, Carter took office after defeating incumbent Republican Preside ...

and his landslide loss in the

1980 presidential election; the hostages were formally released into United States custody the day after the signing of the

Algiers Accords, just minutes after American President

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

was

sworn into office. In Iran, the crisis strengthened the prestige of

Ayatollah

Ayatollah ( ; fa, آیتالله, āyatollāh) is an honorific title for high-ranking Twelver Shia clergy in Iran and Iraq that came into widespread usage in the 20th century.

Etymology

The title is originally derived from Arabic word ...

Ruhollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

and the political power of

theocrats who opposed any normalization of relations with the West. The crisis also led to American economic

sanctions against Iran, which further weakened ties between the two countries.

Background

1953 coup d'état

During the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the

British and the

Soviet governments

invaded and occupied Iran, forcing the first Pahlavi monarch,

Reza Shah Pahlavi to abdicate in favor of his eldest son,

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 Octob ...

. The two nations claimed that they acted preemptively in order to stop Reza Shah from aligning his petroleum-rich country with

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. However, the Shah's declaration of neutrality, and his refusal to allow Iranian territory to be used to train or supply

Soviet troops, were probably the real reasons for the invasion of Iran.

The United States did not participate in the invasion but it secured Iran's independence after the war ended by applying intense diplomatic

pressure on the Soviet Union which forced it to withdraw from Iran in 1946.

By the 1950s,

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 Octob ...

was engaged in a power struggle with Iran's prime minister,

Mohammad Mosaddegh, an immediate descendant of the preceding

Qajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic origin ...

. Mosaddegh led a general strike, demanding an increased share of the nation's petroleum revenue from the

Anglo-Iranian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling number ...

which was operating in Iran. The UK retaliated by reducing the amount of revenue which the Iranian government received. In 1953, the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

and

MI6 helped Iranian royalists depose Mosaddegh in a military ''

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' codenamed

Operation Ajax

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

, allowing the Shah to extend his power. For the next two decades the Shah reigned as an

absolute monarch, "disloyal" elements within the state were purged. The U.S. continued to support the Shah after the coup, with the CIA training the

Iranian secret police. In the subsequent decades of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, various economic, cultural, and political issues united Iranian opposition against the Shah and led to his eventual overthrow.

Carter administration

Months before the

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dyna ...

, on New Year's Eve 1977, U.S. President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

further angered anti-Shah Iranians with a televised toast to Pahlavi, claiming that the Shah was "beloved" by his people. After the revolution commenced in February 1979 with the return of the Ayatollah

Khomeini, the American Embassy was occupied and its staff held hostage briefly. Rocks and bullets had broken so many of the embassy's front-facing windows that they were replaced with

bulletproof glass. The embassy's staff was reduced to just over 60 from a high of nearly one thousand earlier in the decade.

[ Bowden, p. 19]

The

Carter administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the 39th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. A Democrat from Georgia, Carter took office after defeating incumbent Republican Preside ...

tried to mitigate anti-American feeling by promoting a new relationship with the ''de facto'' Iranian government and continuing military cooperation in hopes that the situation would stabilize. However, on October 22, 1979, the United States permitted the Shah, who had

lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). In current usage the name usually refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include en ...

, to enter

New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center for medical treatment. The State Department had discouraged this decision, understanding the political delicacy.

But in response to pressure from influential figures including former

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

and

Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is a nonprofit organization that is independent and nonpartisan. CFR is based in New York Ci ...

Chairman

David Rockefeller, the Carter administration decided to grant it.

[ Farber, p. 122]

The Shah's admission to the United States intensified Iranian revolutionaries' anti-Americanism and spawned rumors of another U.S.–backed coup that would re-install him.

Khomeini, who had been exiled by the shah for 15 years, heightened the rhetoric against the "

Great Satan", as he called the U.S, talking of "evidence of American plotting." In addition to ending what they believed was American sabotage of the revolution, the hostage takers hoped to depose the

provisional revolutionary government of Prime Minister

Mehdi Bazargan

Mehdi Bazargan ( fa, مهدی بازرگان; 1 September 1907 – 20 January 1995) was an Iranian scholar, academic, long-time pro-democracy activist and head of Iran's interim government. He was appointed prime minister in February 1979 by Ay ...

, which they believed was plotting to normalize relations with the U.S. and extinguish Islamic revolutionary order in Iran. The occupation of the embassy on November 4, 1979, was also intended as leverage to demand the return of the Shah to stand trial in Iran in exchange for the hostages.

A later study claimed that there had been no American plots to overthrow the revolutionaries, and that a CIA intelligence-gathering mission at the embassy had been "notably ineffectual, gathering little information and hampered by the fact that none of the three officers spoke the local language,

Persian." Its work, the study said, was "routine, prudent espionage conducted at diplomatic missions everywhere."

Prelude

First attempt

On the morning of February 14, 1979, the

Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took a Marine named

Kenneth Kraus hostage. Ambassador

William H. Sullivan

William Healy Sullivan (October 12, 1922 – October 11, 2013) was an American Foreign Service career officer who served as ambassador to Laos from 1964 to 1969, the Philippines from 1973 to 1977, and Iran from 1977 to 1979.

Early life and care ...

surrendered the embassy to save lives, and with the assistance of Iranian Foreign Minister

Ebrahim Yazdi, returned the embassy to U.S. hands within three hours.

Kraus was injured in the attack, kidnapped by the militants, tortured, tried, and convicted of murder. He was to be executed, but President Carter and Sullivan secured his release within six days.

This incident became known as the Valentine's Day Open House.

Second attempt

The next attempt to seize the American Embassy was planned for September 1979 by

Ebrahim Asgharzadeh

Ebrahim Asgharzadeh ( fa, ابراهیم اصغرزاده) is an Iranian political activist and politician. He served as a member of the 3rd Majlis (Iran's legislature) from 1988–1992 and as a member of the first City Council of Tehran from 19 ...

, a student at the time. He consulted with the heads of the Islamic associations of Tehran's main universities, including the

University of Tehran

The University of Tehran (Tehran University or UT, fa, دانشگاه تهران) is the most prominent university located in Tehran, Iran. Based on its historical, socio-cultural, and political pedigree, as well as its research and teaching pro ...

,

Sharif University of Technology

Sharif University of Technology (SUT; fa, دانشگاه صنعتی شریف) is a public research university in Tehran, Iran. It is widely considered as the nation's most prestigious and leading institution for science, technology, enginee ...

,

Amirkabir University of Technology

Amirkabir University of Technology (AUT) ( fa, دانشگاه صنعتی امیرکبیر), also called the Tehran Polytechnic, is a public technological university located in Tehran, Iran. Founded in 1928, AUT is the second oldest technical uni ...

(Polytechnic of Tehran), and

Iran University of Science and Technology. They named their group

Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line.

Asgharzadeh later said there were five students at the first meeting, two of whom wanted to target the Soviet Embassy because the USSR was "a

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

and anti-God regime". Two others,

Mohsen Mirdamadi and

Habibolah Bitaraf

Habibolah Bitaraf ( fa, حبیبالله بیطرف) is an Iranian reformist politician. He was Energy Minister for 8 years during Mohammad Khatami presidency. He also served as provincial governor of Yazd.

He was nominated as the energy ...

, supported Asgharzadeh's chosen target: the United States. "Our aim was to object against the American government by going to their embassy and occupying it for several hours," Asgharzadeh said. "Announcing our objections from within the occupied compound would carry our message to the world in a much more firm and effective way." Mirdamadi told an interviewer, "We intended to detain the diplomats for a few days, maybe one week, but no more."

Masoumeh Ebtekar

Masoumeh Ebtekar ( fa, معصومه ابتکار; born 21 September 1960) was the former Vice President of Iran for Women and Family Affairs, from August 9, 2017, to September 1, 2021. She previously headed Department of Environment from 1997 t ...

, the spokeswoman for the Iranian students during the crisis, said that those who rejected Asgharzadeh's plan did not participate in the subsequent events.

The students observed the procedures of the

Marine Security Guards from nearby rooftops overlooking the embassy. They also drew on their experiences from the recent revolution, during which the U.S. Embassy grounds were briefly occupied. They enlisted the support of police officers in charge of guarding the embassy and of the Islamic

Revolutionary Guards

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC; fa, سپاه پاسداران انقلاب اسلامی, Sepāh-e Pāsdārān-e Enghelāb-e Eslāmi, lit=Army of Guardians of the Islamic Revolution also Sepāh or Pasdaran for short) is a branch o ...

.

According to the group and other sources, Ayatollah Khomeini did not know of the plan beforehand. The students had wanted to inform him, but according to the author

Mark Bowden

Mark Robert Bowden (; born July 17, 1951) is an American journalist and writer. He is a national correspondent for ''The Atlantic''. He is best known for his book '' Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War'' (1999) about the 1993 U.S. military r ...

, Ayatollah

Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha persuaded them not to. Khoeiniha feared that the government would use the police to expel the students as they had the occupiers in February. The provisional government had been appointed by Khomeini, and so Khomeini was likely to go along with the government's request to restore order. On the other hand, Khoeiniha knew that if Khomeini first saw that the occupiers were faithful supporters of him (unlike the leftists in the first occupation) and that large numbers of pious Muslims had gathered outside the embassy to show their support for the takeover, it would be "very hard, perhaps even impossible," for him to oppose the takeover, and this would paralyze the Bazargan administration, which Khoeiniha and the students wanted to eliminate.

Supporters of the takeover stated that their motivation was fear of another American-backed coup against their popular revolution.

Takeover

On November 4, 1979, one of the demonstrations organized by Iranian student unions loyal to Khomeini erupted into an all-out conflict right outside the walled compound housing the U.S. Embassy.

At about 6:30 a.m., the ringleaders gathered between three hundred and five hundred selected students and briefed them on the battle plan. A female student was given a pair of metal cutters to break the chains locking the embassy's gates and hid them beneath her

chador.

At first, the students planned a symbolic occupation, in which they would release statements to the press and leave when government security forces came to restore order. This was reflected in placards saying: "Don't be afraid. We just want to sit in." When the embassy guards brandished firearms, the protesters retreated, with one telling the Americans, "We don't mean any harm." But as it became clear that the guards would not use deadly force and that a large, angry crowd had gathered outside the compound to cheer the occupiers and jeer the hostages, the plan changed. According to one embassy staff member, buses full of demonstrators began to appear outside the embassy shortly after the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line broke through the gates.

[ Bowden]

As Khomeini's followers had hoped, Khomeini supported the takeover. According to Foreign Minister Yazdi, when he went to

Qom

Qom (also spelled as "Ghom", "Ghum", or "Qum") ( fa, قم ) is the seventh largest metropolis and also the seventh largest city in Iran. Qom is the capital of Qom Province. It is located to the south of Tehran. At the 2016 census, its pop ...

to tell Khomeini about it, Khomeini told him to "go and kick them out." But later that evening, back in Tehran, Yazdi heard on the radio that Khomeini had issued a statement supporting the seizure, calling it "the second revolution" and the embassy an "

American spy den in Tehran."

The Marines and embassy staff were blindfolded by the occupiers, and then paraded in front of assembled photographers. In the first couple of days, many of the embassy workers who had sneaked out of the compound or had not been there at the time of the takeover were rounded up by Islamists and returned as hostages. Six American diplomats managed to avoid capture and took refuge in the British Embassy before being transferred to the Canadian Embassy. In a joint covert operation known as the

Canadian caper, the Canadian government and the CIA managed to smuggle them out of Iran on January 28, 1980, using Canadian passports and a cover story that identified them as a film crew. Others went to the Swedish Embassy in Tehran for three months.

A State Department diplomatic cable of November 8, 1979, details "A Tentative, Incomplete List of U.S. Personnel Being Held in the Embassy Compound."

Motivations

The Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line demanded that Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi return to Iran for trial and execution. The U.S. maintained that the Shah – who was to die less than a year later, in July 1980 – had come to America for medical attention. The group's other demands included that the U.S. government apologize for its interference in the internal affairs of Iran, including the overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddegh in 1953, and that

Iran's frozen assets in the United States be released.

The initial plan was to hold the embassy for only a short time, but this changed after it became apparent how popular the takeover was and that Khomeini had given it his full support.

Some attributed the decision not to release the hostages quickly to President Carter's failure to immediately deliver an ultimatum to Iran. His initial response was to appeal for the release of the hostages on humanitarian grounds and to share his hopes for a strategic

anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

alliance with the Ayatollah. As some of the student leaders had hoped, Iran's moderate prime minister, Bazargan, and his cabinet resigned under pressure just days after the takeover.

The duration of the hostages' captivity has also been attributed to internal Iranian revolutionary politics. As Ayatollah Khomeini told Iran's president:

This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections.

Leftist

People's Mujahedin of Iran supported the taking of hostages at the US embassy.

According to scholar

Daniel Pipes

Daniel Pipes (born September 9, 1949) is an American historian, writer, and commentator. He is the president of the Middle East Forum, and publisher of its ''Middle East Quarterly'' journal. His writing focuses on American foreign policy and the ...

, writing in 1980, the

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

-leaning leftists and the Islamists shared a common antipathy toward market-based reforms under the late Shah, and both subsumed individualism, including the unique identity of women, under conservative, though contrasting, visions of collectivism. Accordingly, both groups favored the Soviet Union over the United States in the early months of the Iranian Revolution.

The Soviets, and possibly their allies

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

,

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, and East Germany, were suspected of providing indirect assistance to the participants in the takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. The

PLO under

Yasser Arafat provided personnel, intelligence liaisons, funding, and training for Khomeini's forces before and after the revolution, and was suspected of playing a role in the embassy crisis.

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

reportedly praised Khomeini as a revolutionary anti-imperialist who could find common cause between revolutionary leftists and anti-American Islamists. Both expressed disdain for modern

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and a preference for authoritarian collectivism.

Cuba and its socialist ally Venezuela, under

Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician who was president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013, except for a brief period in 2002. Chávez was also leader of the Fifth Republ ...

, would later form

ALBA

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kin ...

in alliance with the Islamic Republic as a counter to

neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent f ...

American influence.

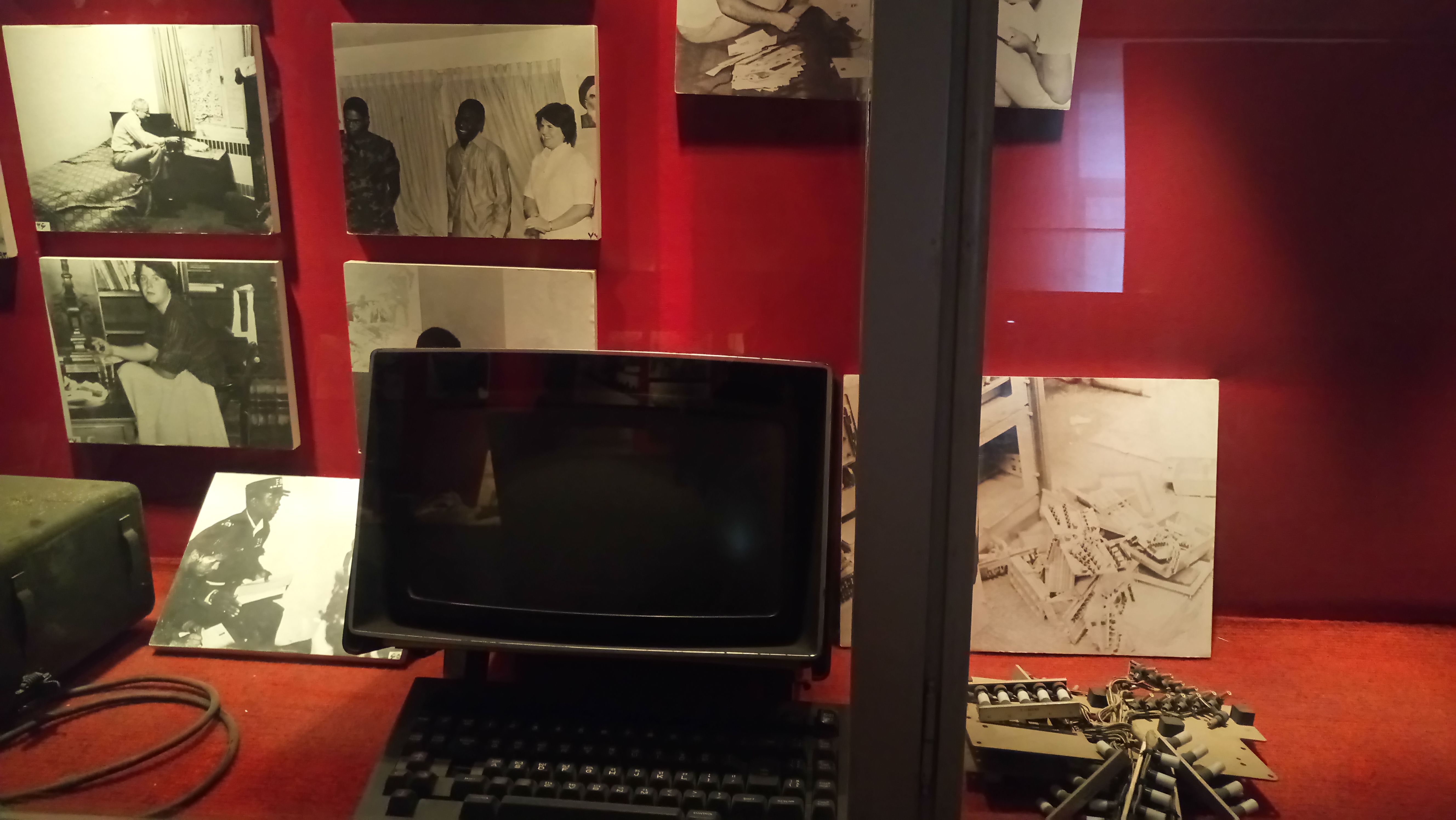

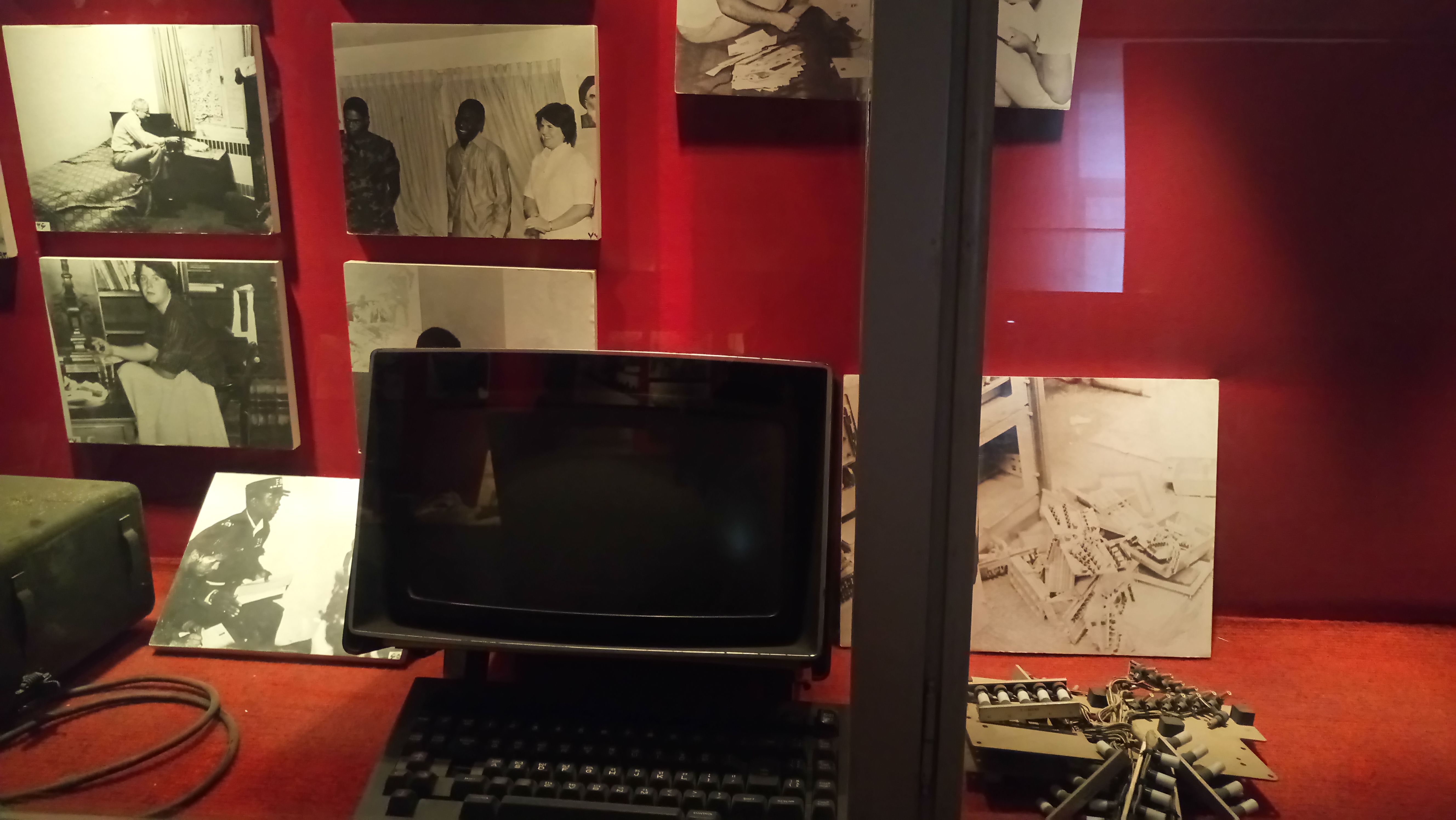

Revolutionary teams displayed secret documents purportedly taken from the embassy, sometimes painstakingly reconstructed after

shredding,

to buttress their claim that the U.S. was trying to destabilize the new regime.

By embracing the hostage-taking under the slogan "America can't do a thing," Khomeini rallied support and deflected criticism of his controversial

theocratic constitution, which was scheduled for a referendum vote in less than one month. The referendum was successful, and after the vote, both leftists and theocrats continued to use allegations of pro-Americanism to suppress their opponents: relatively moderate political forces that included the Iranian Freedom Movement, the

National Front, Grand Ayatollah

Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, and later President

Abolhassan Banisadr. In particular, carefully selected diplomatic dispatches and reports discovered at the embassy and released by the hostage-takers led to the disempowerment and resignation of moderate figures such as Bazargan. The failed rescue attempt and the political danger of any move seen as accommodating America delayed a negotiated release of the hostages. After the crisis ended, leftists and theocrats turned on each other, with the stronger theocratic group annihilating the left.

Documents discovered inside the American embassy

Supporters of the takeover claimed that in 1953, the American Embassy had been used as a "den of spies" from which the coup was organized. Later, documents which suggested that some of the members of the embassy's staff had been working with the Central Intelligence Agency were found Inside the embassy. Later, the CIA confirmed its role and that of MI6 in ''Operation Ajax''. After the Shah entered the United States, Ayatollah Khomeini called for street demonstrations.

Revolutionary teams displayed secret documents purportedly taken from the embassy, sometimes painstakingly reconstructed after

shredding,

in order to buttress their claim that "the Great Satan" (the U.S.) was trying to destabilize the new regime with the assistance of Iranian moderates who were in league with the U.S. The documents – including telegrams, correspondence, and reports from the U.S.

State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

and the CIA – were published in a series of books which were titled ''Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den'' ( fa, اسناد لانه جاسوسی امریكا). According to a 1997

Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who w ...

bulletin, by 1995, 77 volumes of ''Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den'' had been published. Many of these volumes are now available online.

The 444-day crisis

Living conditions of the hostages

The hostage-takers, declaring their solidarity with other "oppressed minorities" and declaring their respect for "the special place of

women in Islam," released one woman and two

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

on November 19.

[Efty, Alex; 'If Shah Not Returned, Khomeini Sets Trial for Other Hostages'; '' Kentucky New Era'', November 20, 1979, pp. 1–2] Before release, these hostages were required by their captors to hold a press conference in which Kathy Gross and William Quarles praised the revolution's aims, but four further women and six African-Americans were released the following day.

According to the then United States Ambassador to Lebanon,

John Gunther Dean, the 13 hostages were released with the assistance of the Palestine Liberation Organization, after

Yassir Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

and

Abu Jihad personally traveled to Tehran to secure a concession. The only African-American hostage not released that month was Charles A. Jones, Jr. One more hostage, a white man named

Richard Queen, was released in July 1980 after he became seriously ill with what was later diagnosed as

multiple sclerosis

Multiple (cerebral) sclerosis (MS), also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata or disseminated sclerosis, is the most common demyelinating disease, in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This ...

. The remaining 52 hostages were held until January 1981, up to 444 days of captivity.

The hostages were initially held at the embassy, but after the takers took the cue from the failed rescue mission, the detainees were scattered around Iran in order to make a single rescue attempt impossible. Three high-level officials –

Bruce Laingen,

Victor L. Tomseth

Victor L. Tomseth (born April 14, 1941) is a former American diplomat and U.S. Ambassador (1993–1996) to Laos. He was Deputy Chief of Mission in Tehran, Iran and was among the Americans taken hostage by the Iranians from 1979 to 1981.

Early ...

, and Mike Howland – were at the Foreign Ministry at the time of the takeover. They stayed there for several months, sleeping in the ministry's formal dining room and washing their socks and underwear in the bathroom. At first, they were treated as diplomats, but after the provisional government fell, the treatment of them deteriorated. By March, the doors to their living space were kept "chained and padlocked."

By midsummer 1980, the Iranians had moved the hostages to prisons in Tehran to prevent escapes or rescue attempts and to improve the logistics of guard shifts and food deliveries. The final holding area, from November 1980 until their release, was the

Teymur Bakhtiar

Teymur Bakhtiar ( fa, تیمور بختیار; 1914 – 12 August 1970) was an Iranian general and the founder and head of SAVAK from 1956 to 1961 when he was dismissed by the Shah. In 1970, SAVAK agents assassinated him in Iraq.

He was an as ...

mansion in Tehran, where the hostages were finally given tubs, showers, and hot and cold running water. Several foreign diplomats and ambassadors – including the former Canadian ambassador

Ken Taylor – visited the hostages over the course of the crisis and relayed information back to the U.S. government, including dispatches from Laingen.

Iranian propaganda stated that the hostages were "guests" and it also stated that they were being treated with respect. Asgharzadeh, the leader of the students, described the original plan as a nonviolent and symbolic action in which the students would use their "gentle and respectful treatment" of the hostages to dramatize the offended sovereignty and dignity of Iran to the entire world. In America, an Iranian

chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassado ...

, Ali Agha, stormed out of a meeting with an American official, exclaiming: "We are not mistreating the hostages. They are being very well taken care of in Tehran. They are our guests."

The actual treatment of the hostages was far different. They described beatings, theft, and fear of bodily harm. Two of them, William Belk and Kathryn Koob, recalled being paraded blindfolded before an angry, chanting crowd outside the embassy. Others reported having their hands bound "day and night" for days or even weeks, long periods of solitary confinement, and months of being forbidden to speak to one another or to stand, walk, or leave their space unless they were going to the bathroom. All of the hostages "were threatened repeatedly with execution, and took it seriously." The hostage-takers played

Russian roulette with their victims.

One hostage, Michael Metrinko, was kept in solitary confinement for several months. On two occasions, when he expressed his opinion of Ayatollah Khomeini, he was severely punished. The first time, he was kept in handcuffs for two weeks, and the second time, he was beaten and kept alone in a freezing cell for two weeks.

Another hostage, U.S. Army medic Donald Hohman, went on a

hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

for several weeks, and two hostages attempted

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

. Steve Lauterbach broke a water glass and slashed his wrists after being locked in a dark basement room with his hands tightly bound. He was found and rushed to the hospital by guards. Jerry Miele, a CIA communications technician, smashed his head into the corner of a door, knocking himself unconscious and cutting a deep gash. "Naturally withdrawn" and looking "ill, old, tired, and vulnerable," Miele had become the butt of his guards' jokes, and they had rigged up a mock electric chair to emphasize the fate that awaited him. His fellow hostages applied

first aid

First aid is the first and immediate assistance given to any person with either a minor or serious illness or injury, with care provided to preserve life, prevent the condition from worsening, or to promote recovery. It includes initial i ...

and raised the alarm, and he was taken to a hospital after a long delay which was caused by the guards.

Other hostages described threats to boil their feet in oil (Alan B. Golacinski), cut their eyes out (Rick Kupke), or kidnap and kill a disabled son in America and "start sending pieces of him to your wife" (David Roeder).

Four hostages tried to escape, and all of them were punished with stretches of solitary confinement when their escape attempts were discovered.

Queen, the hostage who was sent home because of his

multiple sclerosis

Multiple (cerebral) sclerosis (MS), also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata or disseminated sclerosis, is the most common demyelinating disease, in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This ...

, first developed dizziness and numbness in his left arm six months before his release. At first, the Iranians misdiagnosed his symptoms as a reaction to drafts of cold air. When warmer confinement did not help, he was told that it was "nothing" because the symptoms would disappear soon. Over the months, the numbness spread to his right side, and the dizziness worsened until he "was literally flat on his back, unable to move without growing dizzy and throwing up."

The cruelty of the Iranian prison guards became "a form of slow torture." The guards often withheld mail – telling one hostage, Charles W. Scott, "I don't see anything for you, Mr. Scott. Are you sure your wife has not found another man?" – and the hostages' possessions went missing.

As the hostages were taken to the aircraft that would fly them out of Tehran, they were led through a gauntlet of students forming parallel lines and shouting, "Marg bar Amrika" ("

death to America

Death to America ( fa, مرگ بر آمریکا, translit=Marg bar Āmrikā; ) is an anti-American political slogan. It is used in Iran,Arash KaramiKhomeini Orders Media to End 'Death to America' Chant, Iran Pulse, October 13, 2013 Afghanistan, ...

"). When the pilot announced that they were out of Iran, the "freed hostages went wild with happiness. Shouting, cheering, crying, clapping, falling into one another's arms."

Impact in the United States

In the United States, the hostage crisis created "a surge of patriotism" and left "the American people more united than they have been on any issue in two decades."

The hostage-taking was seen "not just as a diplomatic affront," but as a "declaration of war on diplomacy itself."

["Doing Satan's Work in Iran", ''New York Times'', November 6, 1979.] Television news gave daily updates. In January 1980, the ''CBS Evening News'' anchor

Walter Cronkite began ending each show by saying how many days the hostages had been captive. President Carter applied economic and diplomatic pressure: Oil imports from Iran were ended on November 12, 1979, and with

Executive Order 12170, around US$8 billion of Iranian assets in the United States were frozen by the

Office of Foreign Assets Control

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is a financial intelligence and enforcement agency of the U.S. Treasury Department. It administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions in support of U.S. national security and foreign policy o ...

on November 14.

During the weeks leading up to Christmas in 1979, high school students made cards that were delivered to the hostages.

Community groups across the country did the same, resulting in bales of Christmas cards. The

National Christmas Tree was left dark except for the top star.

At the time, two Trenton, N.J., newspapers – ''The Trenton Times'' and ''the Trentonian'' and perhaps others around the country – printed full-page color American flags in their newspapers for readers to cut out and place in the front windows of their homes as support for the hostages until they were brought home safely.

A severe backlash against Iranians in the United States developed. One

Iranian American

Iranian Americans are United States citizens or nationals who are of Iranian ancestry or who hold Iranian citizenship.

Iranian Americans are among the most highly educated people in the United States. They have historically excelled in busi ...

later complained, "I had to hide my Iranian identity not to get beaten up, even at university."

According to Bowden, a pattern emerged in President Carter's attempts to negotiate the hostages' release: "Carter would latch on to a deal proffered by a top Iranian official and grant minor but humiliating concessions, only to have it scotched at the last minute by Khomeini."

Canadian rescue of hostages

On the day the hostages were seized, six American diplomats evaded capture and remained in hiding at the home of the Canadian diplomat

John Sheardown, under the protection of the Canadian ambassador,

Ken Taylor. In late 1979, the government of Prime Minister

Joe Clark secretly issued an

Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''Kin ...

allowing Canadian passports to be issued to some American citizens so that they could escape. In cooperation with the CIA, which used the cover story of a film project, two CIA agents and the six American diplomats boarded a

Swissair

Swissair AG/ S.A. (German: Schweizerische Luftverkehr-AG; French: S.A. Suisse pour la Navigation Aérienne) was the national airline of Switzerland between its founding in 1931 and bankruptcy in 2002.

It was formed from a merger between Bal ...

flight to

Zurich, Switzerland, on January 28, 1980. Their rescue from Iran, known as the Canadian Caper, was fictionalized in the 1981 film ''

Escape from Iran: The Canadian Caper'' and the 2012 film

''Argo''.

Negotiations for release

Rescue attempts

First rescue attempt

Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance Sr. (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary o ...

, the

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, had argued against the push by

Zbigniew Brzezinski, the

National Security Advisor A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

, for a military solution to the crisis.

Vance, struggling with

gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

, went to Florida on Thursday, April 10, 1980, for a long weekend.

[ On Friday Brzezinski held a newly scheduled meeting of the ]National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

where the president authorized Operation Eagle Claw, a military expedition into Tehran to rescue the hostages.[ Deputy Secretary ]Warren Christopher

Warren Minor Christopher (October 27, 1925March 18, 2011) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician. During Bill Clinton's first term as president, he served as the 63rd United States Secretary of State.

Born in Scranton, North Dakota, ...

, who attended the meeting in Vance's place, did not inform Vance.[ Furious, Vance handed in his resignation on principle, calling Brzezinski "evil."][

Late in the afternoon of April 24, 1980, eight RH‑53D helicopters flew from the aircraft carrier USS ''Nimitz'' to a remote road serving as an airstrip in the Great Salt Desert of Eastern Iran, near Tabas. They encountered severe dust storms that disabled two of the helicopters, which were traveling in complete radio silence. Early the next morning, the remaining six helicopters met up with several waiting Lockheed C-130 Hercules transport aircraft at a landing site and refueling area designated "Desert One".

At this point, a third helicopter was found to be unserviceable, bringing the total below the six deemed vital for the mission. The commander of the operation, Col. Charles Alvin Beckwith, recommended that the mission be aborted, and his recommendation was approved by President Carter. As the helicopters repositioned themselves for refueling, one ran into a C‑130 tanker aircraft and crashed, killing eight U.S. servicemen and injuring several more.

Two hours into the flight, the crew of helicopter No. 6 saw a warning light indicating that a main rotor might be cracked. They landed in the desert, confirmed visually that a crack had started to develop, and stopped flying in accordance with normal operating procedure. Helicopter No. 8 landed to pick up the crew of No. 6, and abandoned No. 6 in the desert without destroying it. The report by Holloway's group pointed out that a cracked helicopter blade could have been used to continue the mission and that its likelihood of catastrophic failure would have been low for many hours, especially at lower flying speeds. The report found that the pilot of No. 6 would have continued the mission if instructed to do so.

When the helicopters encountered two ]dust storm

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are transp ...

s along the way to the refueling point, the second more severe than the first, the pilot of No. 5 turned back because the mine-laying helicopters were not equipped with terrain-following radar. The report found that the pilot could have continued to the refueling point if he had been told that better weather awaited him there, but because of the command for radio silence, he did not ask about the conditions ahead. The report also concluded that "there were ways to pass the information" between the refueling station and the helicopter force "that would have small likelihood of compromising the mission" – in other words, that the ban on communication had not been necessary at this stage.

Helicopter No. 2 experienced a partial hydraulic system

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid cou ...

failure but was able to fly on for four hours to the refueling location. There, an inspection showed that a hydraulic fluid leak had damaged a pump and that the helicopter could not be flown safely, nor repaired in time to continue the mission. Six helicopters was thought to be the absolute minimum required for the rescue mission, so with the force reduced to five, the local commander radioed his intention to abort. This request was passed through military channels to President Carter, who agreed.[ Holloway]

In May 1980, the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

commissioned a Special Operations

Special operations (S.O.) are military activities conducted, according to NATO, by "specially designated, organized, selected, trained, and equipped forces using unconventional techniques and modes of employment". Special operations may include ...

review group of six senior military officers, led by Adm. James L. Holloway III, to thoroughly examine all aspects of the rescue attempt. The group identified 23 issues that were significant in the failure of the mission, 11 of which it deemed major. The overriding issue was operational security

Operations security (OPSEC) is a process that identifies critical information to determine if friendly actions can be observed by enemy intelligence, determines if information obtained by adversaries could be interpreted to be useful to them, a ...

– that is, keeping the mission secret so that the arrival of the rescue team at the embassy would be a complete surprise. This severed the usual relationship between pilots and weather forecasters; the pilots were not informed about the local dust storms. Another security requirement was that the helicopter pilots come from the same unit. The unit picked for the mission was a U.S. Navy mine-laying unit flying CH-53D Sea Stallions; these helicopters were considered the best suited for the mission because of their long range, large capacity, and compatibility with shipboard operations.

After the mission and its failure were made known publicly, Khomeini credited divine intervention on behalf of Islam, and his prestige skyrocketed in Iran. Iranian officials who favored release of the hostages, such as President Bani Sadr, were weakened. In America, President Carter's political popularity and prospects for being re-elected in 1980 were further damaged after a television address on April 25 in which he explained the rescue operation and accepted responsibility for its failure.

Planned second attempt

A second rescue attempt, planned but never carried out, would have used highly modified YMC-130H Hercules aircraft.[Thigpen, (2001), p. 241.] Three aircraft, outfitted with rocket thrusters to allow an extremely short landing and takeoff in the Shahid Shiroudi football stadium near the embassy, were modified under a rushed, top-secret program known as Operation Credible Sport. One crashed during a demonstration at Eglin Air Force Base

Eglin Air Force Base is a United States Air Force (USAF) base in the western Florida Panhandle, located about southwest of Valparaiso in Okaloosa County.

The host unit at Eglin is the 96th Test Wing (formerly the 96th Air Base Wing). The 9 ...

on October 29, 1980, when its braking rockets were fired too soon. The misfire caused a hard touchdown that tore off the starboard wing and started a fire, but all on board survived. After Carter lost the presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

in November, the project was abandoned.

The failed rescue attempt led to the creation of the 160th SOAR, a helicopter aviation Special Operations group.

Release

With the completion of negotiations

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach the desired outcome regarding one or more issues of conflict. It is an interaction between entities who aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement ...

signified by the signing of the Algiers Accords on January 19, 1981, the hostages were released on January 20, 1981. That day, minutes after President Reagan completed his 20‑minute inaugural address after being sworn in

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to giv ...

, the 52 American hostages were released to U.S. personnel.Boeing 727

The Boeing 727 is an American narrow-body airliner that was developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

After the heavy 707 quad-jet was introduced in 1958, Boeing addressed the demand for shorter flight lengths from smaller air ...

-200 commercial airliner (registration 7T-VEM) from Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

to Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, where they were formally transferred to Warren M. Christopher, the representative of the United States, as a symbolic gesture of appreciation for the Algerian government's help in resolving the crisis.Rhein-Main Air Base

Rhein-Main Air Base (located at ) was a United States Air Force air base near the city of Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It was a Military Airlift Command (MAC) and United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) installation, occupying the south side ...

in West Germany and on to an Air Force hospital in Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, where former President Carter, acting as emissary, received them. After medical check-ups and debriefings, the hostages made a second flight to a refueling stop in Shannon, Ireland

Shannon () or Shannon Town (), named after the river near which it stands, is a town in County Clare, Ireland. It was given town status on 1 January 1982. The town is located just off the N19 road, a spur of the N18/M18 road between Limeric ...

, where they were greeted by a large crowd. The released hostages were then flown to Stewart Air National Guard Base in Newburgh, New York. From Newburgh, they traveled by bus to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point and stayed at the Thayer Hotel for three days, receiving a heroes' welcome all along the route. Ten days after their release, they were given a ticker tape parade

A ticker-tape parade is a parade event held in an urban setting, characterized by large amounts of shredded paper thrown onto the parade route from the surrounding buildings, creating a celebratory flurry of paper. Originally, actual ticker ta ...

through the Canyon of Heroes

Broadway () is a road in the U.S. state of New York. Broadway runs from State Street at Bowling Green for through the borough of Manhattan and through the Bronx, exiting north from New York City to run an additional through the Westcheste ...

in New York City.

Aftermath

Iran–Iraq War

The Iraqi invasion of Iran occurred less than a year after the embassy employees were taken hostage. The journalist Stephen Kinzer argues that the dramatic change in American–Iranian relations, from allies to enemies, helped embolden the Iraqi leader, Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

, and that the United States' anger with Iran led it to aid the Iraqis after the war turned against them.

Consequences for Iran

The hostage-taking is considered largely unsuccessful for Iran, as the negotiated settlement with the U.S. did not meet any of Iran's original demands. Iran lost international support for its war against Iraq. However, anti-Americanism intensified and the crisis served to benefit those Iranians who had supported it. Politicians such as Khoeiniha and

The hostage-taking is considered largely unsuccessful for Iran, as the negotiated settlement with the U.S. did not meet any of Iran's original demands. Iran lost international support for its war against Iraq. However, anti-Americanism intensified and the crisis served to benefit those Iranians who had supported it. Politicians such as Khoeiniha and Behzad Nabavi

Behzad Nabavi ( fa, بهزاد نبوی) (born 1941) is an Iranian reformist politician. He served as Deputy Speaker of the Parliament of Iran and was one of the founders of the reformist party Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution Organization. Pr ...

were left in a stronger position, while those associated with – or accused of association with – the U.S. were removed from the political picture. Khomeini biographer, Baqer Moin, described the crisis as "a watershed in Khomeini's life" that transformed him from "a cautious, pragmatic politician" into "a modern revolutionary single-mindedly pursuing a dogma." In Khomeini's statements, ''imperialism'' and ''liberalism'' were "negative words," while ''revolution'' "became a sacred word, sometimes more important than ''Islam''."

The Iranian government commemorates the event every year with a demonstration at the embassy and the burning of an American flag. However, on November 4, 2009, pro-democracy protesters and reformists demonstrated in the streets of Tehran. When the authorities encouraged them to chant "death to America," the protesters instead chanted "death to the dictator" (referring to Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei ( fa, سید علی حسینی خامنهای, ; born 19 April 1939) is a Twelver Shia '' marja and the second and current Supreme Leader of Iran, in office since 1989. He was previously the third presiden ...

) and other anti-government slogans.

Consequences for the United States

Gifts, including lifetime passes to any

Gifts, including lifetime passes to any minor league

Minor leagues are professional sports leagues which are not regarded as the premier leagues in those sports. Minor league teams tend to play in smaller, less elaborate venues, often competing in smaller cities/markets. This term is used in No ...

or Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (A ...

game, were showered on the hostages upon their return to the United States.

In 2000, the hostages and their families tried unsuccessfully to sue Iran under the Antiterrorism Act of 1996. They originally won the case when Iran failed to provide a defense, but the State Department then tried to end the lawsuit, fearing that it would make international relations difficult. As a result, a federal judge ruled that no damages could be awarded to the hostages because of the agreement the United States had made when the hostages were freed.

The former U.S. Embassy building is now used by Iran's government and affiliated groups. Since 2001 it has served as a museum to the revolution. Outside the door, there is a bronze model based on the Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the United States. The copper statue, ...

on one side and a statue portraying one of the hostages on the other.

''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'' reported in 2006 that a group called the Committee for the Commemoration of Martyrs of the Global Islamic Campaign had used the embassy to recruit "martyrdom seekers": volunteers to carry out operations against Western and Israeli

Israeli may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the State of Israel

* Israelis, citizens or permanent residents of the State of Israel

* Modern Hebrew, a language

* ''Israeli'' (newspaper), published from 2006 to 2008

* Guni Israeli (b ...

targets.

Diplomatic relations

The United States and Iran broke off formal diplomatic relations over the hostage crisis. Iran selected Algeria as its protecting power in the United States, transferring the mandate to Pakistan in 1992. The United States selected Switzerland as its protecting power in Iran. Relations are maintained through the Iranian Interests Section of the Pakistani Embassy and the U.S. Interests Section of the Swiss Embassy.

Hostages

There were 66 original captives: 63 of them were taken at the embassy and three of them were captured and held at the Foreign Ministry offices. Three of the hostages were operatives of the CIA. One of them was a chemical engineering student from URI.

Diplomats who evaded capture

* Robert Anders, 54 – consular officer

* Mark J. Lijek, 29 – consular officer

* Cora A. Lijek, 25 – consular assistant

* Henry L. Schatz, 31 – agriculture attaché

* Joseph D. Stafford, 29 – consular officer

* Kathleen F. Stafford, 28 – consular assistant

Hostages who were released on November 19, 1979

* Kathy Gross, 22 – secretary

Hostages who were released on November 20, 1979

* Sgt James Hughes, USAF, 30 – Air Force administrative manager

* Lillian Johnson, 32 – secretary

* Elizabeth Montagne, 42 – secretary

* Lloyd Rollins, 40 – administrative officer

* Capt Neal (Terry) Robinson, USAF, – Air Force military intelligence officer

* Terri Tedford, 24 – secretary

* MSgt Joseph Vincent, USAF, 42 – Air Force administrative manager

* Sgt David Walker, USMC, 25 – Marine Corps embassy guard

* Joan Walsh, 33 – secretary

* Cpl Wesley Williams, USMC, 24 – Marine Corps embassy guard

Hostage who was released in July 1980

* Richard Queen, 28 – vice consul

Hostages who were released on January 1981

* Thomas L. Ahern, Jr. – narcotics control officer (later identified as CIA station chief)

* Clair Cortland Barnes, 35 – communications specialist

* William E. Belk, 44 – communications and records officer

* Robert O. Blucker, 54 – economics officer

* Donald J. Cooke, 25 – vice consul

* William J. Daugherty, 33 – third secretary of U.S. mission (CIA officer)

* LCDR Robert Engelmann, USN, 34 – Navy attaché

* Sgt William Gallegos, USMC, 22 – Marine Corps guard

* Bruce W. German, 44 – budget officer

* IS1 Duane L. Gillette, 24 – Navy communications and intelligence specialist

* Alan B. Golacinski, 30 – chief of embassy security, regional security officer

Regional Security Officer (RSO) is the title given to a special agent of the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) who is in charge of a Regional Security Office. The RSO is the principal security attaché and advisor to the U.S. Ambassador a ...

* John E. Graves, 53 – public affairs officer

* CW3 Joseph M. Hall, USA, 32 – Army attaché

* Sgt Kevin J. Hermening, USMC, 21 – Marine Corps guard

* SFC Donald R. Hohman, USA, 38 – Army medic

* COL Leland J. Holland, USA, 53 – military attaché

* Michael Howland, 34 – assistant regional security officer

* Charles A. Jones, Jr., 40 – communications specialist, teletype operator

* Malcolm K. Kalp, 42 – commercial officer

* Moorhead C. Kennedy, Jr., 50 – economic and commercial officer

* William F. Keough, Jr., 50 – superintendent of the American School in Islamabad (visiting Tehran at time of embassy seizure)

* Cpl Steven W. Kirtley, USMC – Marine Corps guard

* Kathryn L. Koob, 42 – embassy cultural officer (one of two unreleased female hostages)

* Frederick Lee Kupke, 34 – communications officer and electronics specialist

* L. Bruce Laingen, 58 – chargé d'affaires

* Steven Lauterbach, 29 – administrative officer

* Gary E. Lee, 37 – administrative officer

* Sgt Paul Edward Lewis, USMC, 23 – Marine Corps guard

* John W. Limbert, Jr., 37 – political officer

* Sgt James M. Lopez, USMC, 22 – Marine Corps guard

* Sgt John D. McKeel, Jr., USMC, 27 – Marine Corps guard

* Michael J. Metrinko, 34 – political officer

* Jerry J. Miele, 42 – communications officer

* SSgt Michael E. Moeller, USMC, 31 – head of Marine Corps guard unit

* Bert C. Moore, 45 – administration counselor

* Richard Morefield, 51 – consul general

* Capt Paul M. Needham, Jr., USAF, 30 – Air Force logistics staff officer

* Robert C. Ode, 65 – retired foreign service officer on temporary duty in Tehran

* Sgt Gregory A. Persinger, USMC, 23 – Marine Corps guard

* Jerry Plotkin, 45 – civilian businessman visiting Tehran

* MSG Regis Ragan, USA, 38 – Army soldier, defense attaché's office

* Lt Col David M. Roeder, USAF, 41 – deputy Air Force attaché

* Barry M. Rosen, 36 – press attaché

* William B. Royer, Jr., 49 – assistant director of Iran–American Society

* Col Thomas E. Schaefer, USAF, 50 – Air Force attaché

* COL Charles W. Scott, USA, 48 – Army attaché

* CDR Donald A. Sharer, USN, 40 – Naval attaché

* Sgt Rodney V. (Rocky) Sickmann, USMC, 22 – Marine Corps guard

* SSG Joseph Subic, Jr., USA, 23 – military police, Army, defense attaché's office

* Elizabeth Ann Swift, 40 – deputy head of political section (one of two unreleased female hostages)

* Victor L. Tomseth

Victor L. Tomseth (born April 14, 1941) is a former American diplomat and U.S. Ambassador (1993–1996) to Laos. He was Deputy Chief of Mission in Tehran, Iran and was among the Americans taken hostage by the Iranians from 1979 to 1981.

Early ...

, 39 – counselor for political affairs

* Phillip R. Ward, 40 – CIA communications officer

Civilian hostages

A small number of hostages, not captured at the embassy, were taken in Iran during the same time period. All were released by late 1982.

* Jerry Plotkin – American Businessman released January 1981.

* Mohi Sobhani – Iranian American engineer and member of the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century, it initially developed in Iran and parts of the ...

. Released February 4, 1981.

* Zia Nassry – Afghan American. Released November 1982.

* Cynthia Dwyer – American reporter, arrested May 5, 1980, charged with espionage and freed on February 10, 1981.

* Paul Chiapparone and Bill Gaylord – Electronic Data Systems

Electronic all cash BSN acc: 1311729000110205 Data Systems (EDS) was an American multinational information technology equipment and services company headquartered in Plano, Texas which was founded in 1962 by Ross Perot. The company was a s ...

(EDS) employees, rescued by team led by retired United States Army Special Forces

The United States Army Special Forces (SF), colloquially known as the "Green Berets" due to their distinctive service headgear, are a special operations force of the United States Army.

The Green Berets are geared towards nine doctrinal mi ...

Colonel "Bull" Simons, funded by EDS owner Ross Perot

Henry Ross Perot (; June 27, 1930 – July 9, 2019) was an American business magnate, billionaire, politician and philanthropist. He was the founder and chief executive officer of Electronic Data Systems and Perot Systems. He ran an indepe ...

, in 1979.

* Four British missionaries, including John Coleman; his wife, Audrey Coleman; and Jean Waddell; released in late 1981

Hostages who were honored

All State Department and CIA employees who were taken hostage received the State Department Award for Valor

The Award for Valor is an obsolete award of the United States Department of State. It has since been replaced with the Award for Heroism. It was presented to employees of State, USAID and Marine guards assigned to diplomatic and consular facili ...

. Political Officer Michael J. Metrinko received two: one for his time as a hostage and another for his daring rescue of Americans who had been jailed in Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quru River valley in Iran's historic Azerbaijan region between long ridges of vo ...

months before the embassy takeover.Humanitarian Service Medal

The Humanitarian Service Medal (HSM) is a military service medal of the United States Armed Forces which was created on January 19, 1977 by President Gerald Ford under . The medal may be awarded to members of the United States military (inclu ...

was awarded to the servicemen of Joint Task Force 1–79, the planning authority for Operation Rice Bowl/Eagle Claw, who participated in the rescue attempt.

The Air Force Special Operations component of the mission was given the Air Force Outstanding Unit award for performing their part of the mission flawlessly, including evacuating the Desert One refueling site under extreme conditions.

Compensation payments

The Tehran hostages received $50 for each day in captivity after their release. This was paid by the US Government. The deal that freed them reached between the United States and Iran and brokered by Algeria in January 1981 prevented the hostages from claiming any restitution from Iran due to foreign sovereign immunity and an executive agreement known as the ''Algiers Accords'', which barred such lawsuits. After failing in the courts, the former hostages turned to Congress and won support from both Democrats and Republicans, resulting in Congress passing a bill (2015 United States Victims of State Sponsored Terrorism Act SVSST in December 2015 that afforded the hostages compensation from a fund to be financed from fines imposed on companies found guilty of breaking American sanctions against Iran. The bill authorised a payment of US$10,000 for each day in captivity (per hostage) as well as a lump sum of $600,000 in compensation for each of the spouses and children of the Iran hostages. This meant that each hostage would be paid up to US$4.4 million. The first funds into the trust account from which the compensation would be paid came from a part of the $9 billion penalty paid by the Paris-based bank BNP Paribas

BNP Paribas is a French international banking group, founded in 2000 from the merger between Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP, "National Bank of Paris") and Paribas, formerly known as the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. The full name of the grou ...

for violating sanctions against Iran, Cuba and Sudan.

Notable hostage-takers, guards, and interrogators

* Abbas Abdi – reformist, journalist, self-taught sociologist, and social activist.

*

* Abbas Abdi – reformist, journalist, self-taught sociologist, and social activist.

* Hamid Aboutalebi

Hamid Aboutalebi ( fa, حمید ابوطالبی, born 16 June 1957) is a former Iranian diplomat and ambassador. Aboutalebi was previously ambassador of Iran to Australia, the European Union, Belgium, Italy, and a political director general t ...

– former Iranian ambassador to the United Nations.

* Ebrahim Asgharzadeh

Ebrahim Asgharzadeh ( fa, ابراهیم اصغرزاده) is an Iranian political activist and politician. He served as a member of the 3rd Majlis (Iran's legislature) from 1988–1992 and as a member of the first City Council of Tehran from 19 ...

– then a student; later an Iranian political activist and politician, member of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

(1989–1993), and chairman of City Council of Tehran

The Islamic City Council of Tehran ( fa, شورای اسلامی شهر تهران) is the directly elected council that presides over the city of Tehran, elects the mayor of Tehran in a mayor–council government system, and budgets of the M ...

(1999–2003).

* Mohsen Mirdamadi – member of Parliament (2000–2004), head of Islamic Iran Participation Front

The Islamic Iran Participation Front ( fa, جبهه مشارکت ایران اسلامی; ''Jebheye Mosharekate Iran-e Eslaami'') was a reformist political party in Iran. It was sometimes described as the most dominant member within the 2nd of Kho ...

.

* Masoumeh Ebtekar

Masoumeh Ebtekar ( fa, معصومه ابتکار; born 21 September 1960) was the former Vice President of Iran for Women and Family Affairs, from August 9, 2017, to September 1, 2021. She previously headed Department of Environment from 1997 t ...