Inventions in the Muslim world on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following is a list of inventions made in the medieval

The following is a list of inventions made in the medieval

*

*

Mechanical Engineering

*

Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

''History of Science and Technology in Islam'' *

Mechanical Engineering

) It included a dial to display the time. *

The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine

His twin-cylinder

''The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices'', page 273

''Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500'', page 53

A 13th Century Programmable Robot (Archive)

*

*

Qatar Digital Library

- an online portal providing access to previously digitised British Library archive materials relating to Gulf history and Arabic science {{DEFAULTSORT:Inventions of the Islamic Golden Age Science in the medieval Islamic world

Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

, especially during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam'', pp. 245, 250, 256–57. New York University Press

New York University Press (or NYU Press) is a university press that is part of New York University.

History

NYU Press was founded in 1916 by the then chancellor of NYU, Elmer Ellsworth Brown.

Directors

* Arthur Huntington Nason, 1916–1 ...

, . as well as in later states of the Age of the Islamic Gunpowders

The gunpowder empires, or Islamic gunpowder empires, is a collective term coined by Marshall G. S. Hodgson and William H. McNeill at the University of Chicago, referring to three Muslim empires: the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire and the Mugha ...

such as the Ottoman and Mughal empires.

The Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

was a period of cultural, economic and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims re ...

, traditionally dated from the eighth century to the fourteenth century, with several contemporary scholars dating the end of the era to the fifteenth or sixteenth century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(786 to 809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, where scholars from various parts of the world with different cultural backgrounds were mandated to gather and translate all of the world's classical knowledge into the Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and subsequently development in various fields of sciences began. Science and technology in the Islamic world adopted and preserved knowledge and technologies from contemporary and earlier civilizations, including Persia, Egypt, India, China, and Greco-Roman antiquity, while making numerous improvements, innovations and inventions.

List of inventions

Early Caliphates

; 7th century *

*Ghazal

The ''ghazal'' ( ar, غَزَل, bn, গজল, Hindi-Urdu: /, fa, غزل, az, qəzəl, tr, gazel, tm, gazal, uz, gʻazal, gu, ગઝલ) is a form of amatory poem or ode, originating in Arabic poetry. A ghazal may be understood as a ...

: A form of Islamic poetry

Islamic poetry is a form of spoken word written & recited by Muslims. Islamic poetry, and notably Sufi poetry, has been written in many languages including Urdu and Turkish.

Genres of Islamic poetry include Ginans, devotional hymns recited by I ...

that originated from the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

in the late 7th century.

;8th century

*Arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

: The distinctive Arabesque style was developed by the 11th century, having begun in the 8th or 9th century in works like the Mshatta Facade

The Mshatta Facade is the decorated part of the facade of the 8th-century Umayyad residential palace of Qasr Mshatta, one of the Desert Castles of Jordan, which is now installed in the south wing of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany. It is ...

.

*Astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

with angular scale : The astrolabe, originally invented some time between 200 and 150 BC, was further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design, adding circles indicating azimuth

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematical ...

s on the horizon

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This line divides all viewing directions based on whether i ...

.

* Classification of chemical substance

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wit ...

s: The works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

(written c. 850–950), and those of Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(c. 865–925), contain the earliest known classifications of chemical substances.

*Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by ...

: Damascus blades were first manufactured in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

from ingot

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sha ...

s of Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon ...

that were imported from India.

*Gear

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth (called ''cogs''), which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit (convert) torque and speed. The basic ...

ed gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

: Geared gristmills were built in the medieval Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, which were used for grinding grain and other seeds to produce meals

A meal is an eating occasion that takes place at a certain time and includes consumption of food. The names used for specific meals in English vary, depending on the speaker's culture, the time of day, or the size of the meal.

Although they c ...

.

*Modern Oud: Although string instruments existed before Islam, the oud was developed in Islamic music

Islamic music may refer to religious music, as performed in Islamic public services or private devotions, or more generally to musical traditions of the Muslim world. The heartland of Islam is the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, W ...

and was the ancestor of the European lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

.

*Sulfur-mercury theory of metals

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

: First attested in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's ''Sirr al-khalīqa'' ("The Secret of Creation", c. 750–850) and in the works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

(written c. 850–950), the sulfur-mercury theory of metals would remain the basis of all theories of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.

*Tin-glazing

Tin-glazing is the process of giving tin-glazed pottery items a ceramic glaze that is white, glossy and opaque, which is normally applied to red or buff earthenware. Tin-glaze is plain lead glaze with a small amount of tin oxide added.Caiger-Smith, ...

: The earliest tin-glazed pottery appears to have been made in Abbasid Iraq

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

/Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

in the 8th-century. The oldest fragments found to-date were excavated from the palace of Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional ar ...

about north of Baghdad.

* Panemone windmill: The earliest recorded windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

design found was Persian in origin, and was invented around the 7th-9th centuries.

;9th century

* Algebra discipline: Al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronom ...

is considered the father of the algebra discipline. The word ''Algebra'' comes from the Arabic الجبر (''al-jabr'') in the title of his book '' Ilm al-jabr wa'l-muḳābala''. He was the first to treat algebra as an independent discipline in its own right., page 263–277: "In a sense, al-Khwarizmi is more entitled to be called "the father of algebra" than Diophantus because al-Khwarizmi is the first to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake, Diophantus is primarily concerned with the theory of numbers".

*Algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

ic reduction and balancing, cancellation, and like terms: Al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronom ...

introduced reduction and balancing in algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

. It refers to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation, which the term ''al-jabr'' (algebra) originally referred to., ''The Arabic Hegemony'', p. 229: "It is not certain just what the terms ''al-jabr'' and ''muqabalah'' mean, but the usual interpretation is similar to that implied in the translation above. The word ''al-jabr'' presumably meant something like "restoration" or "completion" and seems to refer to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation; the word ''muqabalah'' is said to refer to "reduction" or "balancing" – that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation".

*Automatic control

Automation describes a wide range of technologies that reduce human intervention in processes, namely by predetermining decision criteria, subprocess relationships, and related actions, as well as embodying those predeterminations in machines ...

s: The Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

's preoccupation with automatic control

Automation describes a wide range of technologies that reduce human intervention in processes, namely by predetermining decision criteria, subprocess relationships, and related actions, as well as embodying those predeterminations in machines ...

s distinguishes them from their Greek predecessors, including the Banu Musa's "use of self-operating valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

s, timing devices, delay systems and other concepts of great ingenuity."

*Chemical synthesis

As a topic of chemistry, chemical synthesis (or combination) is the artificial execution of chemical reactions to obtain one or several products. This occurs by physical and chemical manipulations usually involving one or more reactions. In mod ...

of a naturally occurring compound: The oldest known instructions for deriving an inorganic compound ( sal ammoniac or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means appear in the works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

(written c. 850–950).

*Chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

manual: The oldest known chess manual was in Arabic and dates to 840–850, written by Al-Adli ar-Rumi (800–870), a renowned Arab chess player, titled ''Kitab ash-shatranj'' (''Book of Chess''). During the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, many works on shatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

were written, recording for the first time the analysis of opening moves, game problems, the knight's tour

A knight's tour is a sequence of moves of a knight on a chessboard such that the knight visits every square exactly once. If the knight ends on a square that is one knight's move from the beginning square (so that it could tour the board again im ...

, and many more subjects common in modern chess books.

* Automatic crank: The non-manual crank appears in several of the hydraulic devices described by the Banū Mūsā brothers in their ''Book of Ingenious Devices''. These automatically operated cranks appear in several devices, two of which contain an action which approximates to that of a crankshaft

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating shaft containing one or more crankpins, that are driven by the pistons via the connecti ...

, anticipating Al-Jazari

Badīʿ az-Zaman Abu l-ʿIzz ibn Ismāʿīl ibn ar-Razāz al-Jazarī (1136–1206, ar, بديع الزمان أَبُ اَلْعِزِ إبْنُ إسْماعِيلِ إبْنُ الرِّزاز الجزري, ) was a polymath: a scholar, ...

's invention by several centuries and its first appearance in Europe by over five centuries. However, the automatic crank described by the Banu Musa would not have allowed a full rotation, but only a small modification was required to convert it to a crankshaft.

*Conical valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

: A mechanism developed by the Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

, of particular importance for future developments, was the conical valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

, which was used in a variety of different applications.

*Control valve

A control valve is a valve used to control fluid flow by varying the size of the flow passage as directed by a signal from a controller. This enables the direct control of flow rate and the consequential control of process quantities such as pressu ...

: The Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

brothers are credited with the first known use of conical valves as automatic controllers.Donald Routledge Hill

Donald Routledge Hill (6 August 1922 – 30 May 1994)D. A. King, “In Memoriam: Donald Routledge Hill (1922-1994)”, ''Arabic Sciences and Philosophy,'' Volume 5 / Issue 02 / September 1995, pp 297-302 was a British engineer and historian of sc ...

, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", ''Scientific American'', May 1991, p. 64-69. (cf.

The abbreviation ''cf.'' (short for the la, confer/conferatur, both meaning "compare") is used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. Style guides recommend that ''cf.'' be used onl ...

Donald Routledge Hill

Donald Routledge Hill (6 August 1922 – 30 May 1994)D. A. King, “In Memoriam: Donald Routledge Hill (1922-1994)”, ''Arabic Sciences and Philosophy,'' Volume 5 / Issue 02 / September 1995, pp 297-302 was a British engineer and historian of sc ...

Mechanical Engineering

*

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic s ...

and frequency analysis

In cryptanalysis, frequency analysis (also known as counting letters) is the study of the frequency of letters or groups of letters in a ciphertext. The method is used as an aid to breaking classical ciphers.

Frequency analysis is based on ...

: In cryptology

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or ''-logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adver ...

, the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic s ...

was given by Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(also known as "Alkindus" in Europe), in ''A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages''. This treatise includes the first description of the method of frequency analysis.

* Double-seat valve: It was invented by the Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

, and has a modern appearance in their ''Book of Ingenious Devices

The ''Book of Ingenious Devices'' (Arabic: كتاب الحيل ''Kitab al-Hiyal'', Persian: كتاب ترفندها ''Ketab tarfandha'', literally: "The Book of Tricks") is a large illustrated work on mechanical devices, including automata, pub ...

''.

*Farabian theories: three philosophical theories of al-Farabi: the theory of ten intelligences, theory of the intellect and theory of prophecy.

*Food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

s: This was identified by al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

.

*Glass

Glass is a non- crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenchin ...

manufacturing: Abbas ibn Firnas developed the process of creating glass from stones.

* Lusterware: Lustre glazes were applied to pottery in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

in the 9th century; the technique soon became popular in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. Earlier uses of lustre are known.

*Hard soap

Soap is a salt of a fatty acid used in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products. In a domestic setting, soaps are surfactants usually used for washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping. In industrial settings, soaps are us ...

: Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was produced in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, when soap-making became an established industry. Recipes for soap-making are described by Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(c. 865–925), who also gave a recipe for producing glycerine

Glycerol (), also called glycerine in British English and glycerin in American English, is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is sweet-tasting and non-toxic. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids know ...

from olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

. In the Middle East, soap was produced from the interaction of fatty oils and fats with alkali

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a basic, ionic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a ...

. In Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, soap was produced using olive oil together with alkali and lime. Soap was exported from Syria to other parts of the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

and to Europe.

* Mental institute: In 872, Ahmad ibn Tulun

Ahmad ibn Tulun ( ar, أحمد بن طولون, translit=Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn; c. 20 September 835 – 10 May 884) was the founder of the Tulunid dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria between 868 and 905. Originally a Turkic slave-soldier, in 868 I ...

built a hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

that provided care to the insane, which included music therapy.

*Kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning " wax", and was re ...

distillation: Although the Chinese made use of kerosene through extracting and purifying petroleum, the process of distilling crude oil/petroleum into kerosene, as well as other hydrocarbon compounds, was first written about in the 9th century by the Persian scholar Rāzi (or Rhazes). In his ''Kitab al-Asrar'' (''Book of Secrets''), the physician and chemist Razi described two methods for the production of kerosene, termed ''naft abyad'' ("white naphtha"), using an apparatus called an alembic

An alembic (from ar, الإنبيق, al-inbīq, originating from grc, ἄμβιξ, ambix, 'cup, beaker') is an alchemical still consisting of two vessels connected by a tube, used for distillation of liquids.

Description

The complete dis ...

.

*Kerosene lamp

A kerosene lamp (also known as a paraffin lamp in some countries) is a type of lighting device that uses kerosene as a fuel. Kerosene lamps have a wick or mantle as light source, protected by a glass chimney or globe; lamps may be used on a ta ...

: The first description of a simple lamp using crude mineral oil was provided by Persian alchemist al-Razi (Rhazes) in 9th century Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, who referred to it as the "naffatah" in his ''Kitab al-Asrar'' (''Book of Secrets'').

*Minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

: The first known minarets appeared in the early 9th century under Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

rule.

*Music sequencer

A music sequencer (or audio sequencer or simply sequencer) is a device or application software that can record, edit, or play back music, by handling note and performance information in several forms, typically CV/Gate, MIDI, or Open Sound Co ...

and mechanical musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

: The origin of automatic musical instruments dates back to the 9th century, when Persian inventors Banū Mūsā

The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873); Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century); and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th ce ...

brothers invented a hydropower

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of ...

ed organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

using exchangeable cylinders with pins, and also an automatic flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedles ...

playing machine using steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tra ...

. These were the earliest mechanical musical instruments, and the first programmable music sequencers.

* Kamal: The kamal originated with Arab navigators of the late 9th century. The invention of the kamal allowed for the earliest known latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

sailing, and was thus the earliest step towards the use of quantitative

Quantitative may refer to:

* Quantitative research, scientific investigation of quantitative properties

* Quantitative analysis (disambiguation)

* Quantitative verse, a metrical system in poetry

* Statistics, also known as quantitative analysis

...

methods in navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation ...

.

*Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. ...

and research institute

A research institute, research centre, research center or research organization, is an establishment founded for doing research. Research institutes may specialize in basic research or may be oriented to applied research. Although the term often i ...

: The oldest true observatory, in the sense of a specialized research institute

A research institute, research centre, research center or research organization, is an establishment founded for doing research. Research institutes may specialize in basic research or may be oriented to applied research. Although the term often i ...

, was built in 825, the Al-Shammisiyyah observatory, in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, Iraq., in Peter Barrett (2004), ''Science and Theology Since Copernicus: The Search for Understanding'', p. 18, Continuum International Publishing Group

Continuum International Publishing Group was an academic publisher of books with editorial offices in London and New York City. It was purchased by Nova Capital Management in 2005. In July 2011, it was taken over by Bloomsbury Publishing. , all ...

,

*Petroleum distillation

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liquefie ...

: Crude oil

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

was often distilled by Arabic chemists, with clear descriptions given in Arabic handbooks such as those of Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(Rhazes).

*Programmable machine A program is a set of instructions used to control the behavior of a machine. Examples of such programs include:

*The sequence of cards used by a Jacquard loom to produce a given pattern within weaved cloth. Invented in 1801, it used holes in punc ...

and automatic flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedles ...

player: The Banū Mūsā

The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873); Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century); and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th ce ...

brothers invented a programmable automatic flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedles ...

player and which they described in their ''Book of Ingenious Devices

The ''Book of Ingenious Devices'' (Arabic: كتاب الحيل ''Kitab al-Hiyal'', Persian: كتاب ترفندها ''Ketab tarfandha'', literally: "The Book of Tricks") is a large illustrated work on mechanical devices, including automata, pub ...

''. It was the earliest programmable machine.

*Sharbat

Sharbat ( fa, شربت, ; also transliterated as ''shorbot'', ''šerbet'' or ''sherbet'') is a drink prepared from fruit or flower petals. It is a sweet cordial, and usually served chilled. It can be served in concentrated form and eaten with ...

and soft drink

A soft drink (see § Terminology for other names) is a drink

A drink or beverage is a liquid intended for human consumption. In addition to their basic function of satisfying thirst, drinks play important roles in human culture. Common t ...

: In the medieval Middle East, a variety of fruit-flavoured soft drinks were widely drunk, such as sharbat

Sharbat ( fa, شربت, ; also transliterated as ''shorbot'', ''šerbet'' or ''sherbet'') is a drink prepared from fruit or flower petals. It is a sweet cordial, and usually served chilled. It can be served in concentrated form and eaten with ...

, and were often sweetened with ingredients such as sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

, syrup

In cooking, a syrup (less commonly sirup; from ar, شراب; , beverage, wine and la, sirupus) is a condiment that is a thick, viscous liquid consisting primarily of a solution of sugar in water, containing a large amount of dissolved sugars ...

and honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

. Other common ingredients included lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

, apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancest ...

, pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

, tamarind

Tamarind (''Tamarindus indica'') is a leguminous tree bearing edible fruit that is probably indigenous to tropical Africa. The genus ''Tamarindus'' is monotypic, meaning that it contains only this species. It belongs to the family Fabacea ...

, jujube

Jujube (), sometimes jujuba, known by the scientific name ''Ziziphus jujuba'' and also called red date, Chinese date, and Chinese jujube, is a species in the genus '' Ziziphus'' in the buckthorn family Rhamnaceae.

Description

It is a smal ...

, sumac

Sumac ( or ), also spelled sumach, is any of about 35 species of flowering plants in the genus ''Rhus'' and related genera in the cashew family (Anacardiaceae). Sumacs grow in subtropical and temperate regions throughout the world, including Eas ...

, musk

Musk ( Persian: مشک, ''Mushk'') is a class of aromatic substances commonly used as base notes in perfumery. They include glandular secretions from animals such as the musk deer, numerous plants emitting similar fragrances, and artificial sub ...

, mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAE ...

and ice. Middle Eastern drinks later became popular in medieval Europe, where the word "syrup" was derived from Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

.

*Sine quadrant

250px, Sinecal Quadrant or as it is known in Arabic: Rub‘ul mujayyab

The sine quadrant (Arabic: , ), sometimes known as the "sinecal quadrant", was a type of quadrant used by medieval Arabic astronomers. The instrument could be used to measur ...

: A type of quadrant used by medieval Arabic astronomers, it was described by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persians, Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in Mathematics ...

in 9th century Baghdad.

*Scimitar

A scimitar ( or ) is a single-edged sword with a convex curved blade associated with Middle Eastern, South Asian, or North African cultures. A European term, ''scimitar'' does not refer to one specific sword type, but an assortment of different ...

: The curved sword or "scimitar" was widespread throughout the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

from at least the Ottoman period

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, with early examples dating to Abbasid era (9th century) Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plat ...

.

* Sugar mill: Sugar mills first appeared in the medieval Islamic world.Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", ''Technology and Culture'' 46 (1): 1-30 0-1 & 27/ref> They were first driven by watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production ...

s, and then windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

s from the 9th and 10th centuries in what are today Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

.Adam Lucas (2006), ''Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology'', p. 65, Brill Publishers

Brill Academic Publishers (known as E. J. Brill, Koninklijke Brill, Brill ()) is a Dutch international academic publisher founded in 1683 in Leiden, Netherlands. With offices in Leiden, Boston, Paderborn and Singapore, Brill today publishes 2 ...

,

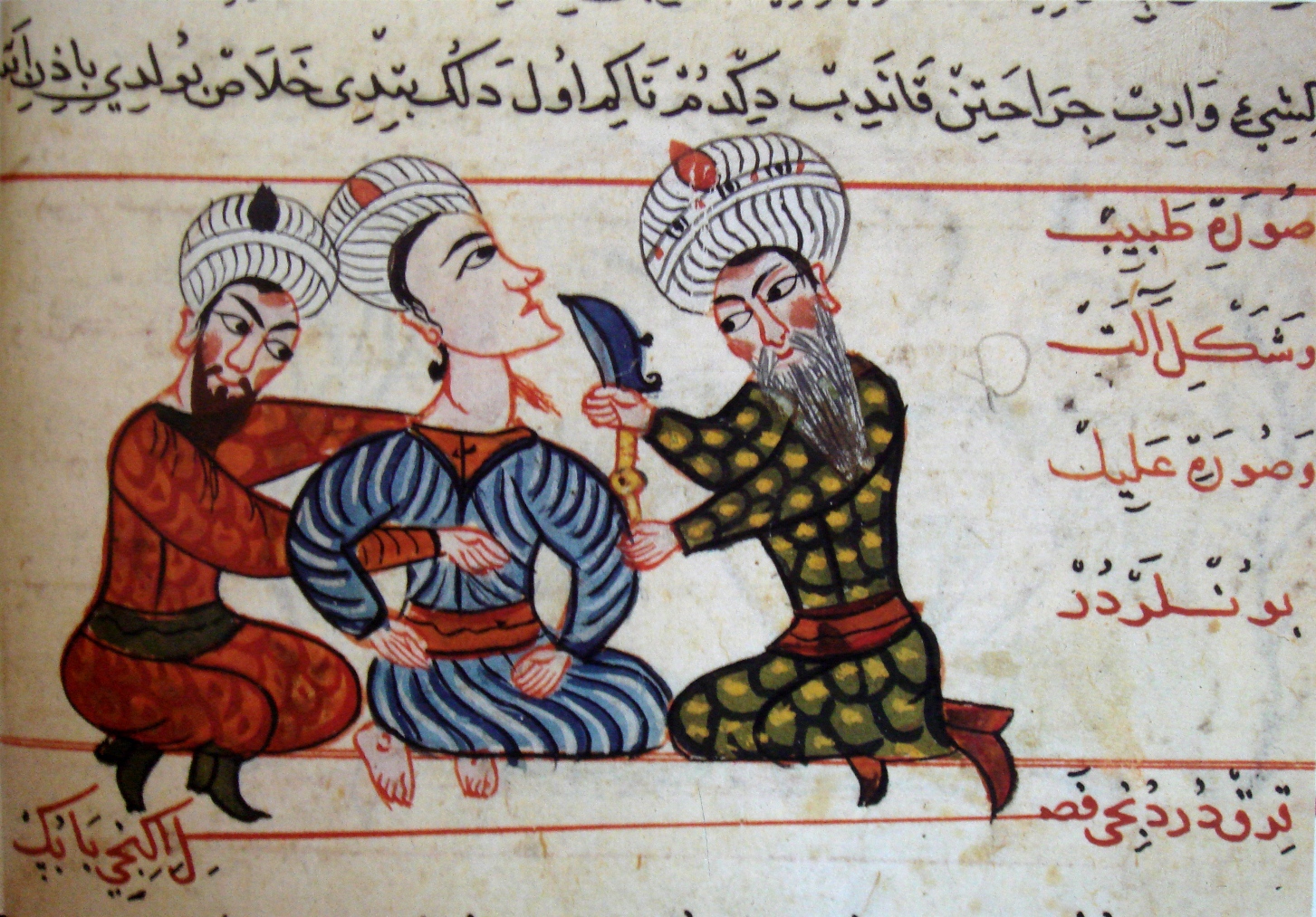

*Early syringe

A syringe is a simple reciprocating pump consisting of a plunger (though in modern syringes, it is actually a piston) that fits tightly within a cylindrical tube called a barrel. The plunger can be linearly pulled and pushed along the inside ...

: The Iraqi/ Egyptian surgeon Ammar ibn Ali al-Mawsili invented an early syringe in the 9th century using a hollow glass tube, providing suction to remove cataracts

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

from patients' eyes.

*Systemic algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

ic solution and completing the square

:

In elementary algebra, completing the square is a technique for converting a quadratic polynomial of the form

:ax^2 + bx + c

to the form

:a(x-h)^2 + k

for some values of ''h'' and ''k''.

In other words, completing the square places a perfe ...

: Al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronom ...

's popularizing treatise on algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

(''The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing

''The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing'' ( ar, كتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة, ; la, Liber Algebræ et Almucabola), also known as ''Al-Jabr'' (), is an Arabic mathematical treati ...

'', c. 813–833 CE) presented the first systematic solution of linear

Linearity is the property of a mathematical relationship ('' function'') that can be graphically represented as a straight line. Linearity is closely related to '' proportionality''. Examples in physics include rectilinear motion, the linear ...

and quadratic equation

In algebra, a quadratic equation () is any equation that can be rearranged in standard form as

ax^2 + bx + c = 0\,,

where represents an unknown value, and , , and represent known numbers, where . (If and then the equation is linear, not qu ...

s. One of his principal achievements in algebra was his demonstration of how to solve quadratic equations by completing the square

:

In elementary algebra, completing the square is a technique for converting a quadratic polynomial of the form

:ax^2 + bx + c

to the form

:a(x-h)^2 + k

for some values of ''h'' and ''k''.

In other words, completing the square places a perfe ...

, for which he provided geometric justifications.

* Thabit numbers: Named after Thabit ibn Qurra Thabit ( ar, ) is an Arabic name for males that means "the imperturbable one". It is sometimes spelled Thabet.

People with the patronymic

* Ibn Thabit, Libyan hip-hop musician

* Asim ibn Thabit, companion of Muhammad

* Hassan ibn Sabit (died 674 ...

*Throttling

A throttle is any mechanism by which the power or speed of an engine is controlled.

Throttle or throttling may also refer to:

Fiction

* ''Throttle'' (film), a 2005 thriller

* ''Throttle'' (novella), a 2009 novella by Stephen King and his son Jo ...

valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

: It appears for the first time in the Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

's ''Book of Ingenious Devices

The ''Book of Ingenious Devices'' (Arabic: كتاب الحيل ''Kitab al-Hiyal'', Persian: كتاب ترفندها ''Ketab tarfandha'', literally: "The Book of Tricks") is a large illustrated work on mechanical devices, including automata, pub ...

''.

*Variable structure control

Variable structure control (VSC) is a form of discontinuous nonlinear control. The method alters the dynamics of a nonlinear system by application of a high-frequency ''switching control''. The state-feedback control law is ''not'' a continuous f ...

: Two-step level controls for fluids, a form of discontinuous variable structure control

Variable structure control (VSC) is a form of discontinuous nonlinear control. The method alters the dynamics of a nonlinear system by application of a high-frequency ''switching control''. The state-feedback control law is ''not'' a continuous f ...

s, was developed by the Banu Musa

Banu or BANU may refer to:

* Banu (name)

* Banu (Arabic), Arabic word for "the sons of" or "children of"

* Banu (makeup artist), an Indian makeup artist

* Banu Chichek, a character in the ''Book of Dede Korkut''

* Bulgarian Agrarian National ...

brothers.

* Wind-powered gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

: The first wind-powered gristmills were built in the 9th and 10th centuries in what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.

*Windpump

A windpump is a type of windmill which is used for pumping water.

Windpumps were used to pump water since at least the 9th century in what is now Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. The use of wind pumps became widespread across the Muslim world an ...

: Windpumps were used to pump water since at least the 9th century in what is now Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

.

;10th century

*Alhazen's problem

Alhazen's problem, also known as Alhazen's billiard problem, is a mathematical problem in geometrical optics first formulated by Ptolemy in 150 AD.

It is named for the 11th-century Arab mathematician Alhazen (''Ibn al-Haytham'') who presented a g ...

: A theorem by ibn al-Haytham solved only in 1997 by Neumann.

*Arabic numerals

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: , , , , , , , , and . They are the most commonly used symbols to write decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such a ...

: The modern Arabic numeral symbols originate from Islamic North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

in the 10th century. A distinctive Western Arabic variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals

The Eastern Arabic numerals, also called Arabic-Hindu numerals or Indo–Arabic numerals, are the symbols used to represent numerical digits in conjunction with the Arabic alphabet in the countries of the Mashriq (the east of the Arab world) ...

began to emerge around the 10th century in the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

and Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

(sometimes called ''ghubar'' numerals, though the term is not always accepted), which are the direct ancestor of the modern Arabic numerals used throughout the world.

* Binomial theorem: The first formulation of the binomial theorem and the table of binomial coefficient can be found in a work by Al-Karaji

( fa, ابو بکر محمد بن الحسن الکرجی; c. 953 – c. 1029) was a 10th-century Persian mathematician and engineer who flourished at Baghdad. He was born in Karaj, a city near Tehran. His three principal surviving works a ...

, quoted by Al-Samaw'al

Al-Samawʾal ibn Yaḥyā al-Maghribī ( ar, السموأل بن يحيى المغربي, ; c. 1130 – c. 1180), commonly known as Samau'al al-Maghribi, was a mathematician, Islamic astronomy, astronomer and Islamic medicine, physician. Born to ...

in his "al-Bahir".

* Cauchy-Riemann Integral: Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

gave a simple form of this.

*Decimal fractions

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers of the Hindu–Arabic numeral ...

: Decimal fractions were first used by Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi in the 10th century.

*Experimental scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

: Expounded and practised by ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

*Fountain pen

A fountain pen is a writing instrument which uses a metal nib (pen), nib to apply a Fountain pen ink, water-based ink to paper. It is distinguished from earlier dip pens by using an internal reservoir to hold ink, eliminating the need to repeat ...

: An early historical mention of what appears to be a reservoir pen dates back to the 10th century. According to Ali Abuzar Mari (d. 974) in his ''Kitab al-Majalis wa 'l-musayarat'', the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah

Abu Tamim Ma'ad al-Muizz li-Din Allah ( ar, ابو تميم معد المعزّ لدين الله, Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Muʿizz li-Dīn Allāh, Glorifier of the Religion of God; 26 September 932 – 19 December 975) was the fourth Fatimid calip ...

demanded a pen that would not stain his hands or clothes, and was provided with a pen that held ink in a reservoir, allowing it to be held upside-down without leaking.

*Law of cotangents

In trigonometry, the law of cotangentsThe Universal Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Pan Reference Books, 1976, page 530. English version George Allen and Unwin, 1964. Translated from the German version Meyers Rechenduden, 1960. is a relationship am ...

: This was first given by Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

.

*Muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

: The origin of the muqarnas can be traced back to the mid-tenth century in northeastern Iran and central North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, as well as the Mesopotamian region.

*Pascal's triangle

In mathematics, Pascal's triangle is a triangular array of the binomial coefficients that arises in probability theory, combinatorics, and algebra. In much of the Western world, it is named after the French mathematician Blaise Pascal, although o ...

: The Persian mathematician Al-Karaji

( fa, ابو بکر محمد بن الحسن الکرجی; c. 953 – c. 1029) was a 10th-century Persian mathematician and engineer who flourished at Baghdad. He was born in Karaj, a city near Tehran. His three principal surviving works a ...

(953–1029) wrote a now lost book which contained the first description of Pascal's triangle.

*Ruffini-Horner Algorithm: Discovered by ibn al-Haytham

*Sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of ce ...

and mural instrument

A mural instrument is an angle measuring instrument mounted on or built into a wall. For astronomical purposes, these walls were oriented so they lie precisely on the meridian. A mural instrument that measured angles from 0 to 90 degrees was call ...

: The first known mural sextant was constructed in Ray

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gr ...

, Iran, by Abu-Mahmud al-Khujandi

Abu Mahmud Hamid ibn al-Khidr al-Khojandi (known as Abu Mahmood Khojandi, Alkhujandi or al-Khujandi, Persian: ابومحمود خجندی, c. 940 - 1000) was a Muslim Transoxanian astronomer and mathematician born in Khujand (now part of Tajikist ...

in 994.

*Shale oil extraction

Shale oil extraction is an industrial process for unconventional oil production. This process converts kerogen in oil shale into shale oil by pyrolysis, hydrogenation, or thermal dissolution. The resultant shale oil is used as fuel oil or up ...

: In the 10th century, the Arab physician Masawaih al-Mardini

Masawaih al-Mardini (Yahyā ibn Masawaih al-Mardini; known as Mesue the Younger) was a Assyrian physician. He was born in Mardin, Upper Mesopotamia. After working in Baghdad, he entered to the service of the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah. H ...

(Mesue the Younger) described a method of extraction of oil from "some kind of bituminous shale".

*Snell's law

Snell's law (also known as Snell–Descartes law and ibn-Sahl law and the law of refraction) is a formula used to describe the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction, when referring to light or other waves passing throug ...

: The law was first accurately described by the Persian scientist Ibn Sahl at the Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

court in 984. In the manuscript ''On Burning Mirrors and Lenses'', ibn Sahl used the law to derive lens shapes that focus light with no geometric aberrations. According to Jim al-Khalili

Jameel Sadik "Jim" Al-Khalili ( ar, جميل صادق الخليلي; born 20 September 1962) is an Iraqi-British theoretical physicist, author and broadcaster. He is professor of theoretical physics and chair in the public engagement in scie ...

, the law should be called ibn Sahl's law.

*Vertical-axle windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

: A small wind wheel operating an organ is described as early as the 1st century AD by Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἥρων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, ''Heron ho Alexandreus'', also known as Heron of Alexandria ; 60 AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in his native city of Alexandria, Roman Egypt. H ...

.Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", ''Archiv für Kulturgeschichte'', Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp.1-30 (10f.) The first vertical-axle windmills were eventually built in Sistan

Sistān ( fa, سیستان), known in ancient times as Sakastān ( fa, سَكاستان, "the land of the Saka"), is a historical and geographical region in present-day Eastern Iran ( Sistan and Baluchestan Province) and Southern Afghanistan ( ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

as described by Muslim geographers. These windmills had long vertical driveshaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connec ...

s with rectangle shaped blades. They may have been constructed as early as the time of the second Rashidun

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

(634-644 AD), though some argue that this account may have been a 10th-century amendment. Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind grains and draw up water, and used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries. Horizontal axle windmills of the type generally used today, however, were developed in Northwestern Europe in the 1180s.

;11th-12th centuries

* Drug trial: Persian physician Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

, in ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

'' (1025), first described use of clinical trials

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, dieta ...

for determining the efficacy of medical drug

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhala ...

s and substances.

*Double-entry bookkeeping system

Double-entry bookkeeping, also known as double-entry accounting, is a method of bookkeeping that relies on a two-sided accounting entry to maintain financial information. Every entry to an account requires a corresponding and opposite entry to ...

: Double-entry bookkeeping was pioneered in the Jewish community of the medieval Middle East.

*Hyperbolic geometry

In mathematics, hyperbolic geometry (also called Lobachevskian geometry or Bolyai–Lobachevskian geometry) is a non-Euclidean geometry. The parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry is replaced with:

:For any given line ''R'' and point ''P ...

: The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

(Alhacen), Omar Khayyám

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm Nīsābūrī (18 May 1048 – 4 December 1131), commonly known as Omar Khayyam ( fa, عمر خیّام), was a polymath, known for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, an ...

and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

on quadrilateral

In geometry a quadrilateral is a four-sided polygon, having four edges (sides) and four corners (vertices). The word is derived from the Latin words ''quadri'', a variant of four, and ''latus'', meaning "side". It is also called a tetragon, ...

s were the first theorems on hyperbolic geometry.Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '' Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science'', Vol. 2, p. 447–494 70 Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

, London and New York:

*Magnifying glass

A magnifying glass is a convex lens that is used to produce a magnified image of an object. The lens is usually mounted in a frame with a handle. A magnifying glass can be used to focus light, such as to concentrate the sun's radiation to c ...

and convex lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

: A convex lens used for forming a magnified image was described in the ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' ( ar, كتاب المناظر, Kitāb al-Manāẓir; la, De Aspectibus or ''Perspectiva''; it, Deli Aspecti) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al- ...

'' by Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

in 1021.

*Mechanical flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device which uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy; a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, as ...

: The mechanical flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device which uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy; a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, as ...

, used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine and, essentially, to allow lifting water from far greater depths (up to 200 metres), was first employed by Ibn Bassal (fl.

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

1038–1075), of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

.

*Mercuric chloride

Mercury(II) chloride (or mercury bichloride, mercury dichloride), historically also known as sulema or corrosive sublimate, is the inorganic chemical compound of mercury and chlorine with the formula HgCl2. It is white crystalline solid and is a ...

(formerly ''corrosive sublimate''): used to disinfect wounds.

*Proof by contradiction

In logic and mathematics, proof by contradiction is a form of proof that establishes the truth or the validity of a proposition, by showing that assuming the proposition to be false leads to a contradiction. Proof by contradiction is also known ...

: Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

(965–1039) developed the method of proof by contradiction

In logic and mathematics, proof by contradiction is a form of proof that establishes the truth or the validity of a proposition, by showing that assuming the proposition to be false leads to a contradiction. Proof by contradiction is also known ...

.

*Spinning wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinnin ...

: The spinning wheel was invented in the Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

by the early 11th century. There is evidence pointing to the spinning wheel being known in the Islamic world by 1030, and the earliest clear illustration of the spinning wheel is from Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, drawn in 1237.

*Steel mill

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

: By the 11th century, much of the Islamic world had industrial steel watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production ...

s in operation, from Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

.

*Weight