The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international

labor union that was founded in

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain.

IWW ideology combines

general union

A general union is a trade union (called ''labor union'' in American English) which represents workers from all industries and companies, rather than just one organisation or a particular sector, as in a craft union or industrial union. A gene ...

ism with

industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The

philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

,

syndicalist, and

anarchist labor movements.

In the 1910s and early 1920s, the IWW achieved many of their short-term goals, particularly in the American West, and cut across traditional guild and union lines to organize workers in a variety of trades and industries. At their peak in August 1917, IWW membership was estimated at more than 150,000, with active wings in the United States, the UK, Canada, and Australia. The extremely high rate of IWW membership

turnover during this era (estimated at 133% per decade) makes it difficult for historians to state membership totals with any certainty, as workers tended to join the IWW in large numbers for relatively short periods (e.g., during

labor strikes and periods of generalized economic distress).

Membership declined dramatically in the late 1910s and 1920s. There were conflicts with other labor groups, particularly the

American Federation of Labor (AFL), which regarded the IWW as too radical, while the IWW regarded the AFL as too conservative and opposed their decision to divide workers on the basis of their crafts.

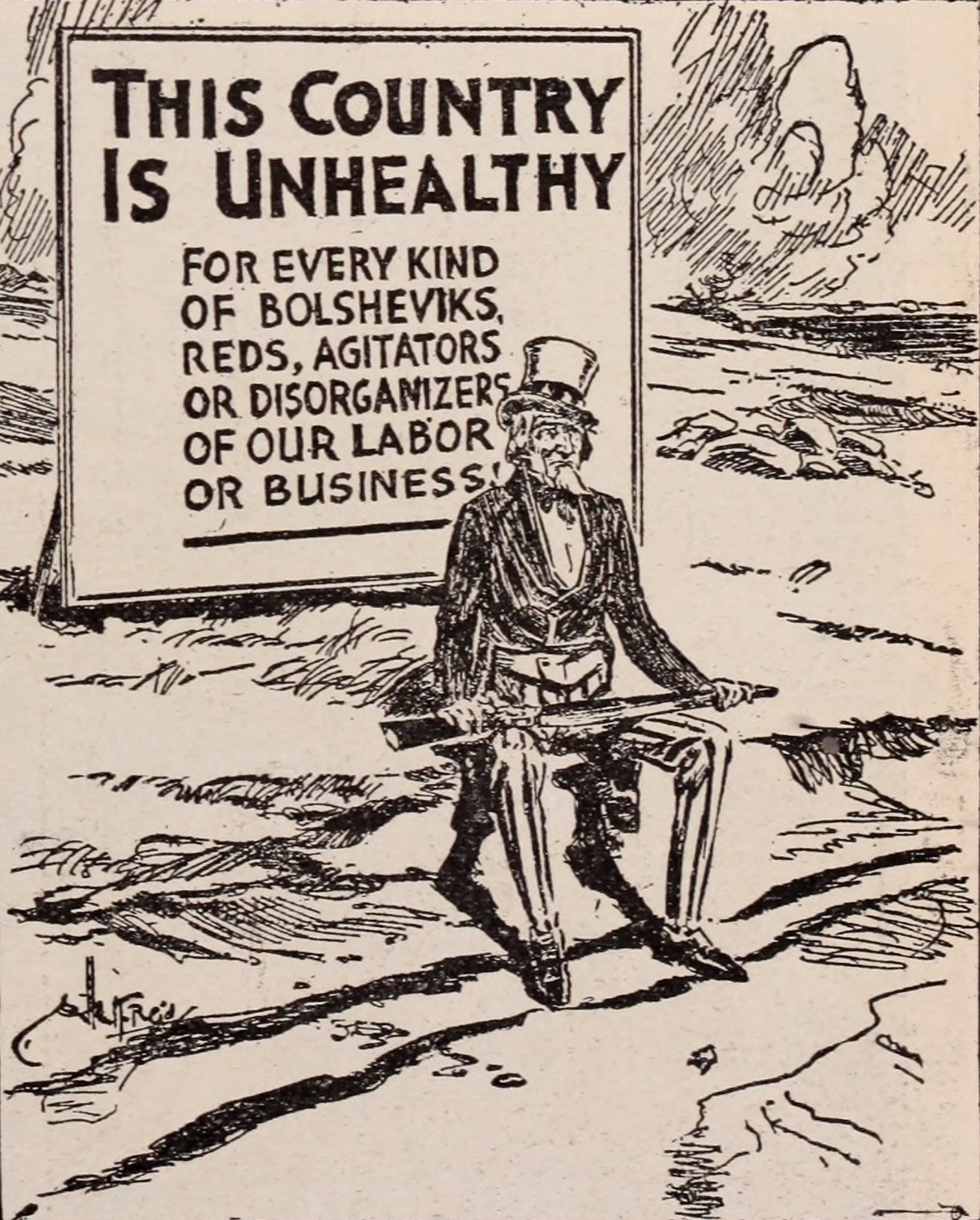

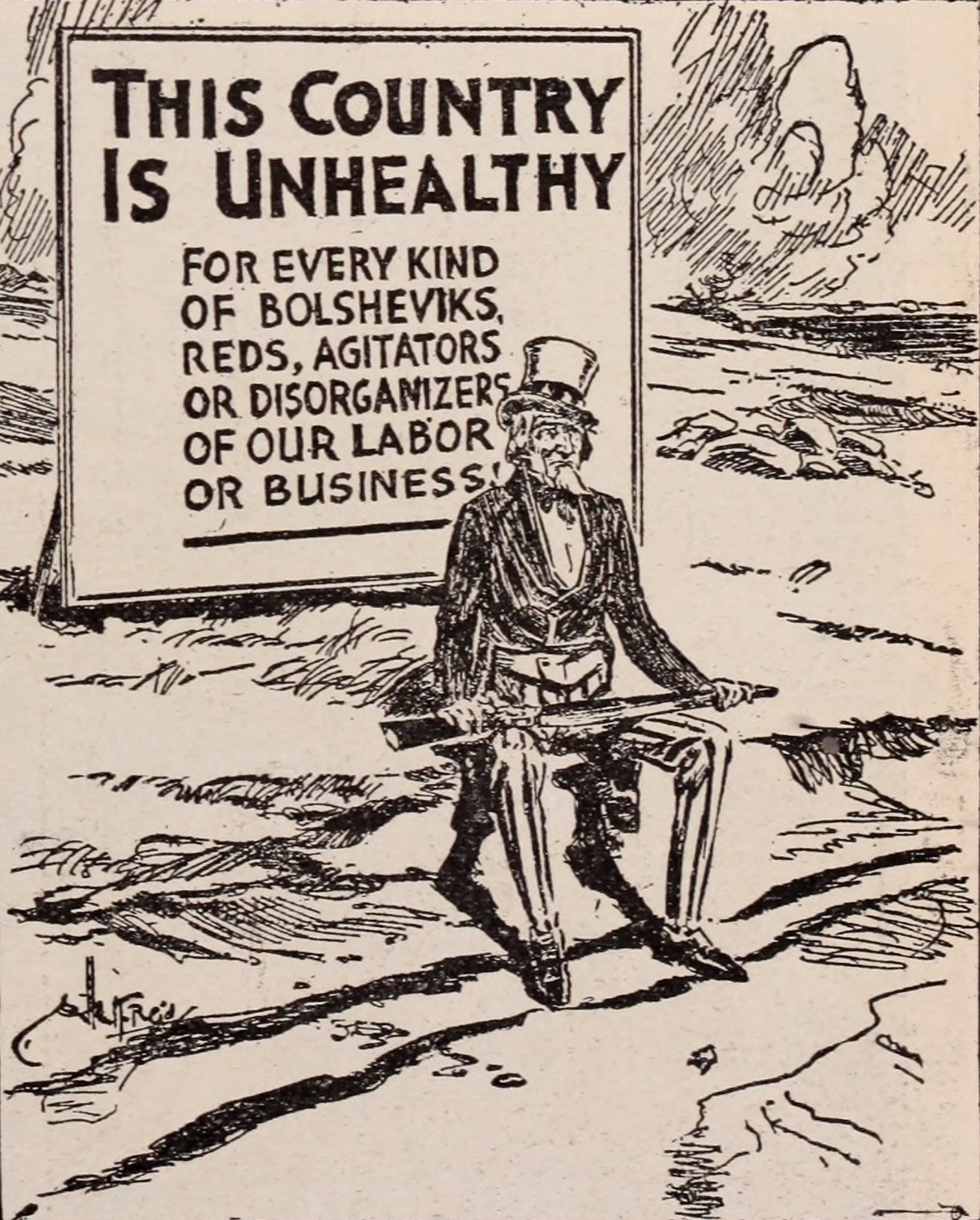

Membership also declined due to government crackdowns on

radical,

anarchist, and

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

groups during the

First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

after World War I. In Canada the IWW was outlawed by the federal government by an

Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''Kin ...

on September 24, 1918.

Probably the most decisive factor in the decline in IWW membership and influence was a

1924 schism in the organization, from which the IWW never fully recovered.

The IWW promotes the concept of "

One Big Union", and contends that all workers should be united as a

social class to supplant

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

and

wage labor

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power under ...

with

industrial democracy

Industrial democracy is an arrangement which involves workers making decisions, sharing responsibility and authority in the workplace. While in participative management organizational designs workers are listened to and take part in the decisi ...

.

It is known for the Wobbly Shop model of

workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in various forms (examples include voting systems, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, systems of appeal) to the workplace. It can be implemented in a variety ...

, in which workers elect their own managers

and other forms of

grassroots democracy

Grassroots democracy is a tendency towards designing political processes that shift as much decision-making authority as practical to the organization's lowest geographic or social level of organization.

Grassroots organizations can have a va ...

(

self-management) are implemented. The IWW does not require its members to

work in a represented workplace, neither does it exclude membership in another labor union.

History

1905–1950

Founding

The first meeting to plan the IWW was held in Chicago in 1904. The six attendees were

Clarence Smith and

Thomas J. Hagerty of the

American Labor Union,

George Estes and

W. L. Hall of the

United Brotherhood of Railway Employees

The United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE) was an industrial labor union established in Canada in 1898, and a separate union established in Oregon in 1901. The two combined in 1902. The union signed up lesser-skilled railway clerks and la ...

,

Isaac Cowan of the U.S. branch of the

Amalgamated Society of Engineers

The Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) was a major British trade union, representing factory workers and mechanics.

History

The history of the union can be traced back to the formation of the Journeymen Steam Engine, Machine Makers' and M ...

, and

William E. Trautmann of the

United Brewery Workmen

The International Union of United Brewery, Flour, Cereal, Soft Drink and Distillery Workers was a trade union, labor union in the United States. The union merged with the Teamsters in 1973.

Early history

The union was founded in 1886 as the Nat ...

.

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

, formerly of the

American Railway Union, and

Charles O. Sherman of the

United Metal Workers

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

were involved but were unable to attend the meeting.

The

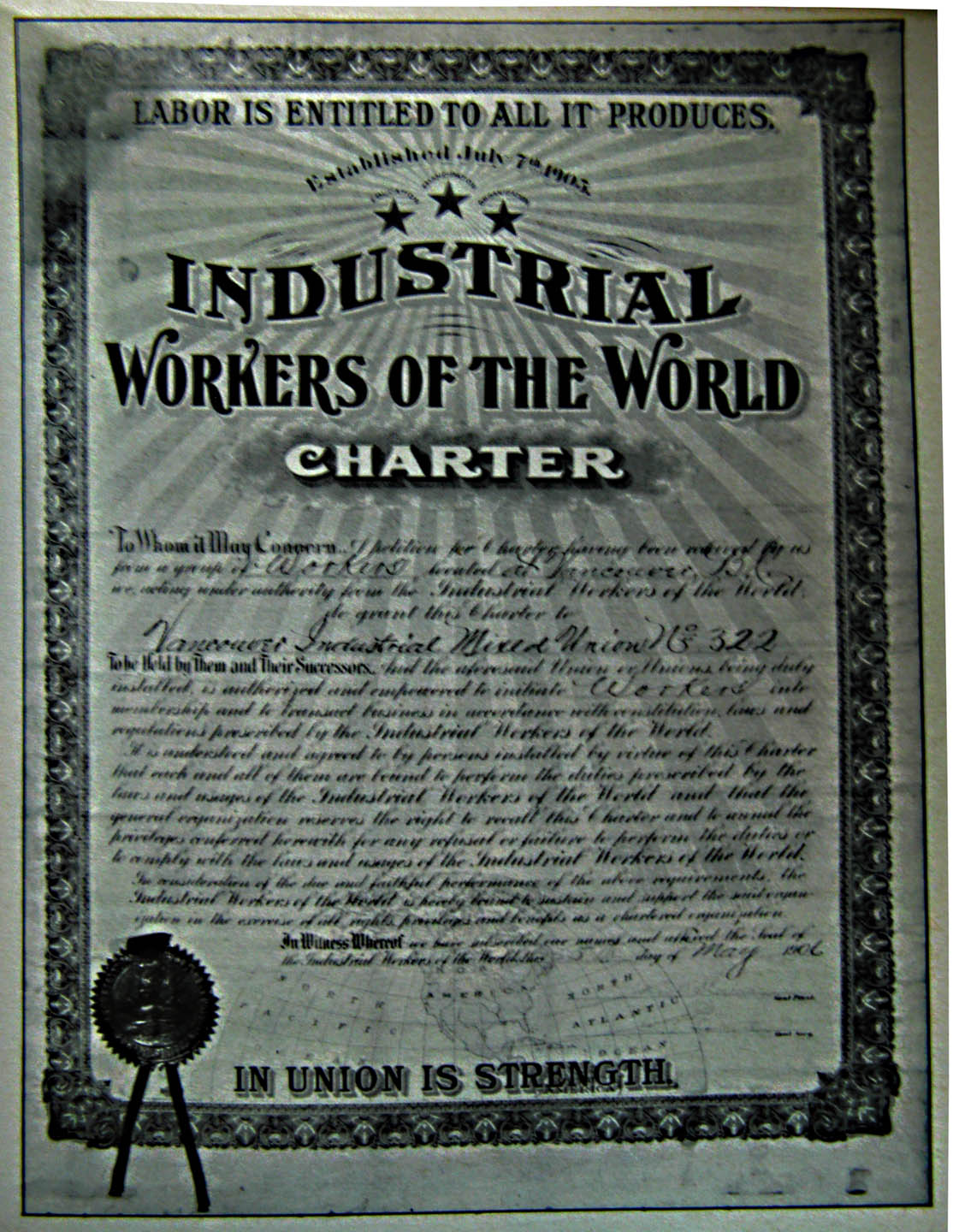

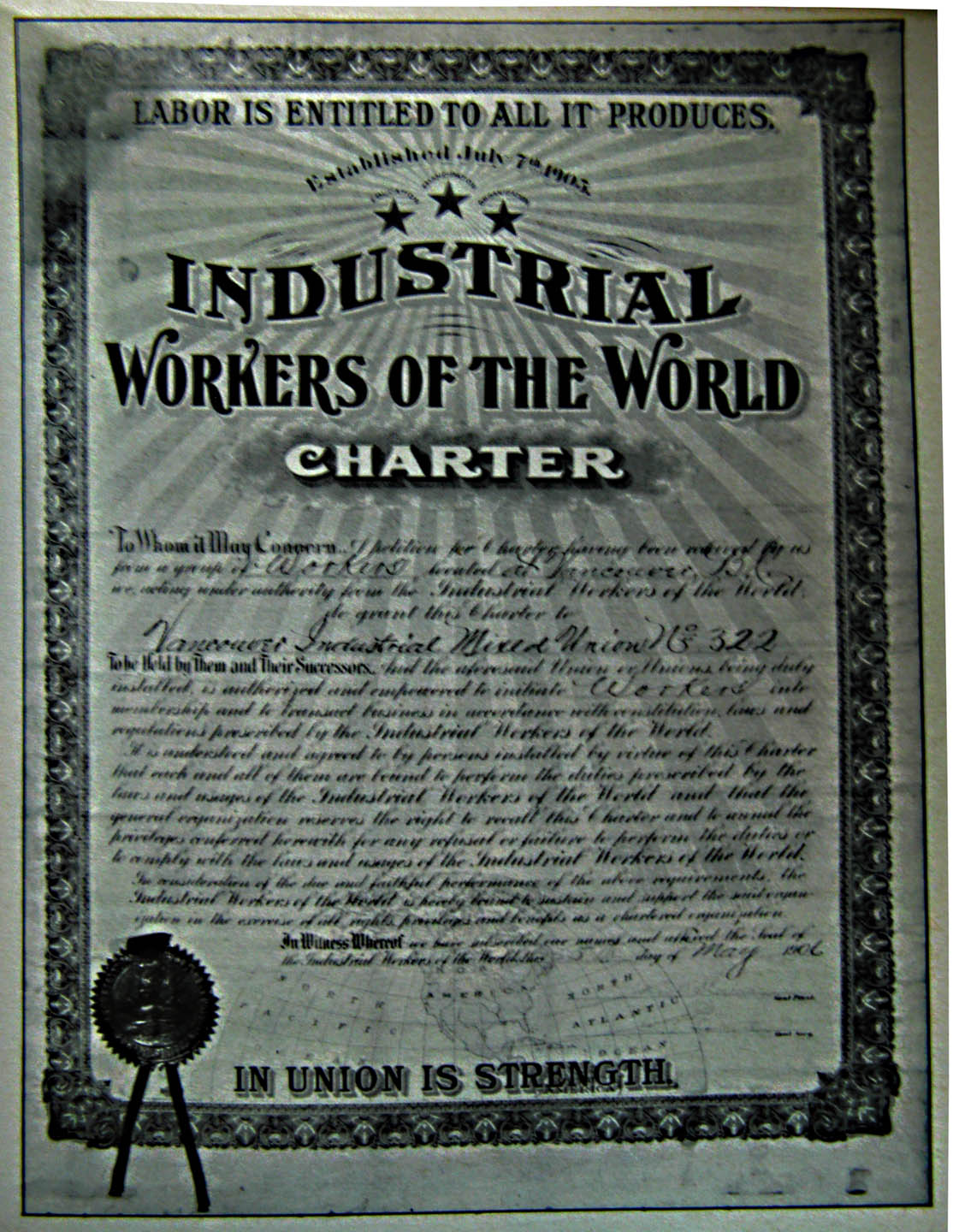

IWW was officially founded in Chicago, Illinois in June 1905. A convention was held of 200

socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

,

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

,

Marxists (primarily members of the

Socialist Party of America and

Socialist Labor Party of America), and radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

) who strongly opposed the policies of the

American Federation of Labor (AFL). The IWW opposed the AFL's acceptance of capitalism and its refusal to include unskilled workers in craft unions.

The convention had taken place on June 27, 1905, and was referred to as the "Industrial Congress" or the "Industrial Union Convention". It would later be known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW.

The IWW's founders included

William D. ("Big Bill") Haywood,

James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

,

Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regarded as the forefather o ...

,

Eugene V. Debs,

Thomas Hagerty,

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

,

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones,

Frank Bohn,

William Trautmann

William Ernst Trautmann (July 1, 1869 – November 18, 1940) was founding general-secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and one of 69 people who initially laid plans for the organization in 1904.

He was born to German parents in ...

,

Vincent Saint John

Vincent Saint John (1876–1929) was an American labor leader and prominent Wobbly, among the most influential radical labor leaders of the 20th century.

Biography

Vincent St. John was born in Newport, Kentucky and was the only son of New York ...

,

Ralph Chaplin, and many others.

The IWW aimed to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class; its

motto

A motto (derived from the Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. Mot ...

was "

an injury to one is an injury to all

An injury to one is an injury to all is a motto popularly used by the Industrial Workers of the World. In his autobiography, Bill Haywood credited David C. Coates with suggesting a labor slogan for the IWW: ''an injury to one is an injury to all' ...

". They saw this as an improvement upon the

Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

's creed, "an injury to one is the concern of all" which the Knights had spoken out in the 1880s. In particular, the IWW was organized because of the belief among many unionists, socialists, anarchists, Marxists, and radicals that the AFL not only had failed to effectively organize the U.S.

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

, but it was causing separation rather than unity within groups of workers by organizing according to narrow craft principles. The Wobblies believed that all workers should organize as a class, a philosophy which is still reflected in the Preamble to the current IWW Constitution:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth.

We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

Instead of the conservative motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work," we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, "Abolition of the wage system."

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old

Prefigurative politics are the modes of organization and social relationships that strive to reflect the future society being sought by the group. According to Carl Boggs, who coined the term, the desire is to embody "within the ongoing political p ...

.

The Wobblies, as they were informally known, differed from other union movements of the time by promotion of

industrial unionism, as opposed to the

craft unionism

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

of the AFL. The IWW emphasized

rank-and-file organization, as opposed to empowering leaders who would bargain with employers on behalf of workers. The early IWW chapters consistently refused to sign contracts, which they believed would restrict workers' abilities to aid each other when called upon. Though never developed in any detail, Wobblies envisioned the

general strike as the means by which the wage system would be overthrown and a new economic system ushered in, one which emphasized people over profit, cooperation over competition.

One of the IWW's most important contributions to the labor movement and broader push towards social justice was that, when founded, it was the only American union to welcome all workers, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians, into the same organization. Many of its early members were immigrants, and some, such as

Carlo Tresca,

Joe Hill and

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union ...

, rose to prominence in the leadership.

Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

formed a sizable portion of the immigrant IWW membership. "Conceivably, the number of Finns belonging to the I.W.W. was somewhere between five and ten thousand." The

Finnish-language

Finnish ( endonym: or ) is a Uralic language of the Finnic branch, spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside of Finland. Finnish is one of the two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedis ...

newspaper of the IWW, ''

Industrialisti'', published in

Duluth, Minnesota

, settlement_type = City

, nicknames = Twin Ports (with Superior), Zenith City

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top: urban Duluth skyline; Minnesota ...

, a center of the mining industry, was the union's only daily paper. At its peak, it ran 10,000 copies per issue. Another Finnish-language Wobbly publication was the monthly ''

Tie Vapauteen'' ("Road to Freedom"). Also of note was the Finnish IWW educational institute, the

Work People's College in Duluth, and the

Finnish Labour Temple in

Port Arthur, Ontario

Port Arthur was a city in Northern Ontario, Canada, located on Lake Superior. In January 1970, it amalgamated with Fort William and the townships of Neebing and McIntyre to form the city of Thunder Bay.

Port Arthur had been the district seat o ...

, Canada, which served as the IWW Canadian administration for several years. Further, many Swedish immigrants, particularly those blacklisted after the 1909 Swedish

General Strike, joined the IWW and set up similar cultural institutions around the Scandinavian Socialist Clubs. This in turn exerted a political influence on the Swedish labor movement's left, that in 1910 formed the Syndicalist union SAC which soon contained a minority seeking to mimick the tactics and strategies of the IWW. One example of the union's commitment to equality was Local 8, a longshoremen's branch in Philadelphia, one of the largest ports in the nation in the WWI era. Led by

Ben Fletcher

Benjamin Harrison Fletcher (April 13, 1890 – 1949) was an early 20th-century African-American labor leader and public speaker. He was a prominent member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or the "Wobblies"), a left-wing trade union whi ...

, an African American, Local 8 had more than 5,000 members, the majority of whom were African American, along with more than a thousand immigrants (primarily Lithuanians and Poles), Irish Americans, and numerous white ethnics.

Divide on political action or direct action

In 1908 a group led by

Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regarded as the forefather o ...

argued that

political action through De Leon's

Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

(SLP) was the best way to attain the IWW's goals. The other faction, led by Vincent Saint John, William Trautmann, and Big Bill Haywood, believed that

direct action in the form of

strikes,

propaganda, and

boycotts was more likely to accomplish sustainable gains for working people; they were opposed to arbitration and to political affiliation. Haywood's faction prevailed, and De Leon and his supporters left the organization, forming their own version of the IWW. The SLP's "

Yellow IWW" eventually took the name

Workers' International Industrial Union, which was disbanded in 1924.

Organizing

The IWW first attracted attention in

Goldfield,

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

in 1906 and during the

Pressed Steel Car Strike of 1909

The Pressed Steel Car strike of 1909, also known as the 1909 McKees Rocks strike, was an American labor strike which lasted from July 13 through September 8. The walkout drew national attention when it climaxed on Sunday August 22 in a bloody b ...

at

McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania

McKees Rocks, also known as "The Rocks", is a borough in Allegheny County in western Pennsylvania, along the south bank of the Ohio River. The population was 5,920 at the time of the 2020 census. It is part of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. In ...

. Further fame was gained later that year, when they took their stand on free speech. The town of

Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the Cana ...

, had outlawed street meetings, and arrested

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union ...

, a Wobbly organizer, for breaking this ordinance. The response was simple but effective: when a fellow member was arrested for speaking, large numbers of people descended on the location and invited the authorities to arrest all of them, until it became too expensive for the town. In Spokane, over 500 people went to jail and four people died. The tactic of

fighting for free speech to popularize the cause and preserve the right to organize openly was used effectively in

Fresno

Fresno () is a major city in the San Joaquin Valley of California, United States. It is the county seat of Fresno County and the largest city in the greater Central Valley region. It covers about and had a population of 542,107 in 2020, maki ...

,

Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, and other locations. In

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

, although there was no particular organizing campaign at stake, vigilantes supported by local officials and powerful businessmen

mounted a particularly brutal counter-offensive.

By 1912 the organization had around 25,000 members, concentrated in the Northwest, among dock workers, agricultural workers in the central states, and in textile and mining areas. The IWW was involved in over 150 strikes, including the

Lawrence textile strike (1912), the

Paterson silk strike (1913), the Tucker Utah strike (June 14, 1913), the

Studebaker strike (1913), and

the Mesabi range (1916). They were also involved in what came to be known as the

Wheatland Hop Riot on August 3, 1913.

Geography

In its first decades, the IWW created more than 900 unions located in more than 350 cities and towns in 38 states and territories of the United States and 5 Canadian provinces. Throughout the country, there were 90 newspapers and periodicals affiliated with the IWW, published in 19 different languages. Members of the IWW were active throughout the country and were involved in the

Seattle General Strike

The Seattle General Strike of 1919 was a five-day general work stoppage by more than 65,000 workers in the city of Seattle, Washington from February 6 to 11. Dissatisfied workers in several unions began the strike to gain higher wages, after t ...

of 1919, were arrested or killed in the

Everett Massacre

The Everett Massacre (also known as Bloody Sunday) was an armed confrontation between local authorities and members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union, commonly called "Wobblies". It took place in Everett, Washington on Sunday, ...

, organized among Mexican workers in the Southwest, became a large and powerful longshoremen's union in Philadelphia, and more.

IWW versus AFL Carpenters, Goldfield, Nevada, 1906-1907

The IWW assumed a prominent role in 1906 and 1907 in the gold-mining boom town of

Goldfield, Nevada

Goldfield is an unincorporated small desert city and the county seat of Esmeralda County, Nevada.

It is the locus of the Goldfield CDP which had a resident population of 268 at the 2010 census, down from 440 in 2000. Goldfield is located ...

. At that time, the Western Federation of Miners was still an affiliate of the IWW (the WFM withdrew from the IWW in the summer of 1907). In 1906, the IWW became so powerful in Goldfield that it could dictate wages and working conditions.

Resisting IWW domination was the AFL-affiliated Carpenters Union. In March 1907, the IWW demanded that the mines deny employment to AFL Carpenters, which led mine owners to challenge the IWW. The mine owners banded together and pledged not to employ any IWW members. The mine and business owners of Goldfield staged a lockout, vowing to remain shut until they had broken the power of the IWW. The lockout prompted a split within the Goldfield workforce, between conservative and radical union members.

The mine owners persuaded the Nevada governor to ask for federal troops. Under the protection of federal troops, the mine owners reopened the mines with non-union labor, breaking the influence of the IWW in Goldfield.

The Haywood trial and the exit of the Western Federation of Miners

Leaders of the Western Federation of Miners such as

Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

and Vincent St. John were instrumental in forming the IWW, and the WFM affiliated with the new union organization shortly after the IWW was formed. The WFM became the IWW's "mining section". However, many in the rank and file of the WFM were uncomfortable with the open radicalism of the IWW, and wanted the WFM to maintain its independence. Schisms between the WFM and IWW had emerged at the annual IWW convention in 1906, when a majority of WFM delegates walked out.

When WFM executives Bill Haywood,

George Pettibone

George A. Pettibone (May 1862 – August 3, 1908) was an Idaho miner. Pettibone was best known as a defendant in trial of three leaders of the Western Federation of Miners for the 1905 assassination by bombing of Frank Steunenberg, former governo ...

, and

Charles Moyer were accused of complicity in the murder of former Idaho governor

Frank Steunenberg

Frank Steunenberg (August 8, 1861December 30, 1905) was the fourth governor of the State of Idaho, serving from 1897 until 1901. He was assassinated in 1905 by one-time union member Harry Orchard, who was also a paid informant for the Cripple C ...

, the IWW used the case to raise funds and support, and paid for the legal defense. However, even the not guilty verdicts worked against the IWW, because the IWW was deprived of martyrs, and at the same time, a large portion of the public remained convinced of the guilt of the accused. The trials caused a bitter split between Haywood and Moyer. The Haywood trial also provoked a reaction within the WFM against violence and radicalism. In the summer of 1907, the WFM withdrew from the IWW, Vincent St. John left the WFM to spend his time organizing the IWW.

Bill Haywood for a time remained a member of both organizations. His murder trial had made Haywood a celebrity, and he was in demand as a speaker for the WFM. However, his increasingly radical speeches became more at odds with the WFM, and in April 1908, the WFM announced that the union had ended Haywood's role as a union representative. Haywood left the WFM, and devoted all his time to organizing for the IWW.

Historian Vernon H. Jensen has asserted that the IWW had a "rule or ruin" policy, under which it attempted to wreck local unions which it could not control. From 1908 to 1921, Jensen and others have written, the IWW attempted to win power in WFM locals which had once formed the federation's backbone. When it could not do so, IWW agitators undermined WFM locals, which caused the national union to shed nearly half its membership.

IWW versus the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners left the IWW in 1907, but the IWW wanted the WFM back. The WFM had made up about a third of the IWW membership, and the western miners were tough union men, and good allies in a labor dispute. In 1908, Vincent St. John tried to organize a stealth takeover of the WFM. He wrote to WFM organizer Albert Ryan, encouraging him to find reliable IWW sympathizers at each WFM local, and have them appointed delegates to the annual convention by pretending to share whatever opinions of that local needed to become a delegate. Once at the convention, they could vote in a pro-IWW slate. St. Vincent promised: "... once we can control the officers of the WFM for the IWW, the big bulk of the membership will go with them." But the takeover did not succeed.

In 1914, Butte, Montana, erupted into

a series of riots as miners dissatisfied with the

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

local at Butte formed a new union, and demanded that all miners join the new union, or be subject to beatings or worse. Although the new rival union had no affiliation with the IWW, it was widely seen as IWW-inspired. The leadership of the new union contained many who were members of the IWW, or agreed with the IWW's methods and objectives. However, the new union failed to supplant the WFM, and the ongoing fight between the two factions had the result that the copper mines of Butte, which had long been a union stronghold for the WFM, became open shops, and the mine owners recognized no union from 1914 until 1934.

IWW versus United Mine Workers, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1916

The IWW clashed with the

United Mine Workers union in April 1916, when the IWW picketed the anthracite mines around Scranton, Pennsylvania, intending, by persuasion or force, to keep UMWA members from going to work. The IWW considered the UMWA too reactionary, because the United Mine Workers negotiated contracts with the mine owners for fixed time periods; the IWW considered that contracts hindered their revolutionary goals. In what a contemporary writer pointed out was a complete reversal of their usual policy, UMWA officials called for police to protect United Mine Workers members who wished to cross the picket lines. The Pennsylvania State Police arrived in force, prevented picket line violence, and allowed the UMWA members to peacefully pass through the IWW picket lines.

The Bisbee Deportation

In November 1916, the 10th convention of the IWW authorized an organizing drive in the Arizona copper mines. Copper was a vital war commodity so mines were working day and night. During the first months of 1917, thousands joined the Metal Mine Workers' Union #800. The focus of the organizing drive was

Bisbee, Arizona

Bisbee is a city in and the county seat of Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, United States. It is southeast of Tucson and north of the Mexican border. According to the 2020 census, the population of the town was 4,923, down from 5,575 ...

, a small town near the Mexican border. Nearly 5000 miners worked in Bisbee's mines. On June 27, 1917, Bisbee's miners went on strike. The strike was effective and non-violent. Demands included the doubling of pay for surface workers, most of them recent immigrants from Mexico, as well as changes in working conditions to make the mines safer. The six hour day was raised agitationally but held in abeyance. In the early hours of July 12, hundreds of armed vigilantes rounded up nearly two thousand strikers, of whom 1186 were deported in cattle cars and dumped in the desert of New Mexico. In the following days, hundreds more were ordered to leave. The strike was broken at gunpoint.

Other organizing drives

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's

Agricultural Workers Organization

The Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO), later known as the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union, was an organization of farm workers throughout the United States and Canada formed on April 15, 1915, in Kansas City. It was supported by, an ...

(AWO) organized more than a hundred thousand migratory farm workers throughout the Midwest and western United States, often signing up and organizing members in the field, in rail yards and in hobo jungles. During this time, the IWW member became synonymous with the hobo riding the rails; migratory farmworkers could scarcely afford any other means of transportation to get to the next jobsite. Railroad boxcars, called "side door coaches" by the hobos, were frequently plastered with

silent agitators from the IWW.

Building on the success of the AWO, the IWW's

Lumber Workers Industrial Union

The Lumber Workers' Industrial Union (LWIU) was a labor union in the United States and Canada which existed between 1917 and 1924. It organised workers in the timber industry and was affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

H ...

(LWIU) used similar tactics to organize

lumberjacks and other timber workers, both in the deep South and the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, between 1917 and 1924. The IWW lumber strike of 1917 led to the

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

and vastly improved working conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Though mid-century historians would give credit to the US Government and "forward thinking lumber magnates" for agreeing to such reforms, an IWW strike forced these concessions.

From 1913 through the mid-1930s, the IWW's Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), proved a force to be reckoned with and competed with AFL unions for ascendance in the industry. Given the union's commitment to international solidarity, its efforts and success in the field come as no surprise. Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers was led by Ben Fletcher, who organized predominantly African-American longshoremen on the Philadelphia and Baltimore waterfronts, but other leaders included the Swiss immigrant Walter Nef, Jack Walsh, E.F. Doree, and the Spanish sailor Manuel Rey. The IWW also had a presence among waterfront workers in

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

,

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

,

,

Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 i ...

,

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

,

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

,

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

,

Eureka

Eureka (often abbreviated as E!, or Σ!) is an intergovernmental organisation for research and development funding and coordination. Eureka is an open platform for international cooperation in innovation. Organisations and companies applying th ...

,

Portland,

Tacoma,

Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

,

Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

as well as in ports in the Caribbean, Mexico, South America, Australia, New Zealand, Germany and other nations. IWW members played a role in the 1934

San Francisco general strike and the other organizing efforts by rank-and-filers within the

International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways. The ILA h ...

up and down the West Coast.

Wobblies also played a role in the sit-down strikes and other organizing efforts by the

United Auto Workers

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) ...

in the 1930s, particularly in Detroit, though they never established a strong union presence there.

Where the IWW did win strikes, such as in Lawrence, they often found it hard to hold onto their gains. The IWW of 1912 disdained

collective bargaining agreement

A collective agreement, collective labour agreement (CLA) or collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is a written contract negotiated through collective bargaining for employees by one or more trade unions with the management of a company (or with an ...

s and preached instead the need for constant struggle against the boss on the shop floor. It proved difficult, however, to maintain that sort of revolutionary enthusiasm against employers. In Lawrence, the IWW lost nearly all of its membership in the years after the strike, as the employers wore down their employees' resistance and eliminated many of the strongest union supporters. In 1938, the IWW voted to allow contracts with employers, so long as they would not undermine any strike.

Government suppression

The IWW's efforts were met with "unparalleled" resistance from Federal, state and local governments in America;

from company management and

labor spies, and from groups of citizens functioning as vigilantes. In 1914, Wobbly

Joe Hill (born Joel Hägglund) was accused of murder in Utah and, on what many regarded as flimsy evidence, was executed in 1915. On November 5, 1916, at

Everett, Washington

Everett is the county seat and largest city of Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is north of Seattle and is one of the main cities in the metropolitan area and the Puget Sound region. Everett is the seventh-largest city in the ...

, a group of deputized businessmen led by Sheriff Donald McRae

attacked Wobblies on the steamer ''

Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

'', killing at least five union members (six more were never accounted for and probably were lost in

Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

). Two members of the police force—one a regular officer and another a deputized citizen from the National Guard Reserve—were killed, probably by "friendly fire". At least five Everett civilians were wounded.

Many IWW members opposed United States participation in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The organization passed a resolution against the war at its convention in November 1916.

This echoed the view, expressed at the IWW's founding convention, that war represents struggles among capitalists in which the rich become richer, and the working poor all too often die at the hands of other workers.

An IWW newspaper, the ''

Industrial Worker

The ''Industrial Worker'', "the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism", is the magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). It is currently released quarterly. The publication is printed and edited by union labor, and is frequently ...

'', wrote just before the U.S. declaration of war: "Capitalists of America, we will fight against you, not for you! There is not a power in the world that can make the working class fight if they refuse." Yet when a declaration of war was passed by the U.S. Congress in April 1917, the IWW's general secretary-treasurer Bill Haywood became determined that the organization should adopt a low profile in order to avoid perceived threats to its existence. The printing of anti-war stickers was discontinued, stockpiles of existing anti-war documents were put into storage, and anti-war propagandizing ceased as official union policy. After much debate on the General Executive Board, with Haywood advocating a low profile and GEB member

Frank Little championing continued agitation, Ralph Chaplin brokered a compromise agreement. A statement was issued that denounced the war, but IWW members were advised to channel their opposition through the legal mechanisms of conscription. They were advised to register for the draft, marking their claims for exemption "IWW, opposed to war."

In spite of the IWW moderating its vocal opposition, the IWW's antiwar stance made it highly unpopular. Frank Little, the IWW's most outspoken war opponent, was lynched in

Butte, Montana, in August 1917, just four months after war had been declared.

During World War I the U.S. government moved strongly against the IWW. On September 5, 1917, U.S.

Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

agents made simultaneous raids on dozens of IWW meeting halls across the country.

Minutes books, correspondence, mailing lists, and publications were seized, with the

U.S. Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

removing five tons of material from the IWW's General Office in Chicago alone.

This seized material was scoured for possible violations of the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

and other laws, with a view to future prosecution of the organization's leaders, organizers, and key activists.

Based in large measure on the documents seized September 5, one hundred and sixty-six IWW leaders were indicted by a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes, under the new Espionage Act.

One hundred and one went on trial en masse before Judge

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his ...

in 1918. Their lawyer was

George Vanderveer of Seattle.

They were all convicted—including those who had not been members of the union for years—and given prison terms of up to twenty years. Sentenced to prison by Judge Landis and released on bail, Haywood fled to the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

where he remained until his death.

In 1917, during an incident known as the

Tulsa Outrage, a group of black-robed Knights of Liberty tarred and feathered seventeen members of the IWW in Oklahoma. The attack was cited as revenge for the

Green Corn Rebellion, a preemptive attack caused by fear of an impending attack on the oil fields and as punishment for not supporting the war effort. The IWW members had been turned over to the Knights of Liberty by local authorities after they were beaten, arrested at their headquarters and convicted of the crime of vagrancy. Five other men who testified in defense of the Wobblies were also fined by the court and subjected to the same torture and humiliations at the hands of the Knights of Liberty.

In 1919, an

Armistice Day

Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day in the Commonwealth and Veterans Day in the United States, is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark the armistice signed between the Allies of World War I and Germany at Compiègne, Fran ...

parade by the

American Legion in

Centralia, Washington

Centralia () is a city in Lewis County, Washington, United States. It is located along Interstate 5 near the midpoint between Seattle and Portland, Oregon. The city had a population of 18,183 at the 2020 census. Centralia is twinned with Ch ...

, turned into a fight between legionnaires and IWW members in which four legionnaires and a Centralia deputy sheriff were shot dead. Which side initiated the violence of the

Centralia massacre is disputed. A number of IWWs were arrested, one of whom,

Wesley Everest, was lynched by a mob that night.

Members of the IWW were prosecuted under various State and federal laws and the 1920

Palmer Raids singled out the foreign-born members of the organization.

Organizational schism and afterwards

IWW quickly recovered from the setbacks of 1919 and 1920, with membership peaking in 1923 (58,300 estimated by dues paid per capita, though membership was likely somewhat higher as the union tolerated delinquent members). But recurring internal debates, especially between those who sought either to centralize or decentralize the organization, ultimately brought about the IWW's 1924 schism.

The twenties witnessed the defection of hundreds of Wobbly leaders (including

Harrison George

Harrison George was a senior Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) leader. He is best remembered as the editor of the official organ of the Profintern's Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat (PPTUS) as well as the party's West Coast newspaper ...

,

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union ...

,

John Reed,

George Hardy,

Charles Ashleigh

Charles Ashleigh (1892–1974) was an English labour activist, writer, and translator who became prominent in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and later the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Life

Ashleigh was born in West Hampstead, Londo ...

,

Earl Browder and, in his Soviet exile,

Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

) and, following a path recounted by

Fred Beal,

thousands of Wobbly rank-and-filers to the Communists and Communist organizations.

At the beginning of the 1949

Smith Act trials, FBI director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

was disappointed when prosecutors indicted fewer CPUSA members than he had hoped, and—recalling the arrests and convictions of over one hundred IWW leaders in 1917—complained to the Justice Department, stating, "the IWW as a subversive menace was crushed and has never revived. Similar action at this time would have been as effective against the Communist Party and its subsidiary organizations."

1950–2000

Taft–Hartley Act

After the passage of the

Taft-Hartley Act in 1946 by Congress, which called for the removal of Communist union leadership, the IWW experienced a loss of membership as differences of opinion occurred over how to respond to the challenge. In 1949, US Attorney General

Tom C. Clark placed the IWW on the

Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations The United States Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) was a list drawn up on April 3, 1947 at the request of the United States Attorney General (and later Supreme Court justice) Tom C. Clark. The list was intended to be a c ...

in the category of "organizations seeking to change the government by unconstitutional means" under

Executive Order 9835

President Harry S. Truman signed United States Executive Order 9835, sometimes known as the "Loyalty Order", on March 21, 1947. The order established the first general loyalty program in the United States, designed to root out communist influence ...

, which offered no means of appeal, and which excluded all IWW members from Federal employment and federally subsidized housing programs (this order was revoked by

Executive Order 10450 in 1953).

At this time, the Cleveland local of the

Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union (MMWIU) was the strongest IWW branch in the United States. Leading figures such as

Frank Cedervall, who had helped build the branch up for over ten years, were concerned about the possibility of raiding from AFL-CIO unions if the IWW had its legal status as a union revoked. In 1950, Cedervall led the 1500-member MMWIU national organization to split from the IWW, as the

Lumber Workers Industrial Union

The Lumber Workers' Industrial Union (LWIU) was a labor union in the United States and Canada which existed between 1917 and 1924. It organised workers in the timber industry and was affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

H ...

had almost thirty years earlier. Unfortunately for the MMWIU, this act would not save it. Despite its brief affiliation with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, it would face serious raiding from AFL and CIO and would be defunct by the late 1950s, less than ten years after separating from the IWW.

The loss of the MMWIU, at the time the IWW's largest industrial union, was almost a deathblow to the IWW. The union's membership fell to its lowest level in the 1950s during the

Second Red Scare

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origina ...

, and by 1955, the union's fiftieth anniversary, it was near extinction, though it still appeared on government lists of Communist-led groups.

1960s rejuvenation

The 1960s

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, anti-war protests, and various university student movements brought new life to the IWW, albeit with many fewer new members than the great organizing drives of the early part of the 20th century.

The first signs of new life for the IWW in the 1960s would be organizing efforts among students in San Francisco and Berkeley, which were hotbeds of student radicalism at the time. This targeting of students would result in a Bay Area branch of the union with over a hundred members in 1964, almost as many as the union's total membership in 1961. Wobblies old and new would unite for one more "free speech fight": Berkeley's

Free Speech Movement

The Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a massive, long-lasting student protest which took place during the 1964–65 academic year on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley. The Movement was informally under the central leadership of Be ...

. Riding on this high, the decision in 1967 to allow college and university students to join the

Education Workers Industrial Union (IU 620) as full members spurred campaigns in 1968 at the

University of Waterloo

The University of Waterloo (UWaterloo, UW, or Waterloo) is a public research university with a main campus in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is on of land adjacent to "Uptown" Waterloo and Waterloo Park. The university also operates ...

in Ontario, the

University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee (UW–Milwaukee, UWM, or Milwaukee) is a public urban research university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It is the largest university in the Milwaukee metropolitan area and a member of the University of Wiscon ...

, and the

University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

in Ann Arbor.

The IWW would send representatives to

Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s, and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships ...

conventions in 1967, 1968, and 1969, and as the SDS collapsed into infighting, the IWW would gain members who were fleeing this discord. These changes would have a profound effect on the union, which by 1972 would have sixty-seven percent of members under the age of thirty, with a total of nearly five hundred members.

The IWW's links to the 60s counterculture led to organizing campaigns at counterculture businesses, as well as a wave of over two dozen co-ops affiliating with the IWW under its

Wobbly Shop model in the 1960s to 1980s. These businesses were primarily in printing, publishing, and food distribution; from underground newspapers and radical print shops to community co-op grocery stores. Some of the printing and publishing industry co-ops and job shops included

Black & Red (Detroit), Glad Day Press (New York),

RPM Press (Michigan),

New Media Graphics (Ohio),

Babylon Print (Wisconsin),

Hill Press (Illinois),

Lakeside (

Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the county seat of Dane County and the capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census the population was 269,840, making it the second-largest city in Wisconsin by population, after Milwaukee, and the 80th-lar ...

), Harbinger (

Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is List of municipalities in South Carolina, the second-largest ...

), Eastown Printing in Grand Rapids, Michigan (where the IWW negotiated a contract in 1978),

and La Presse Populaire (Montréal). This close affiliation with radical publishers and printing houses sometimes led to legal difficulties for the union, such as when La Presse Populaire was shut down in 1970 by provincial police for publishing pro-

FLQ materials, which were banned at the time under an official censorship law. Also in 1970, the

San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United Stat ...

, "street journal" ''El Barrio'' became an official IWW shop. In 1971 its office was attacked by an organization calling itself the

Minutemen, and IWW member Ricardo Gonzalves was indicted for criminal syndicalism along with two members of the

Brown Berets.

These ties to anti-authoritarian and radical artistic and literary currents would link the IWW even more heavily to the 60s counterculture, exemplified by the publication in Chicago in the 1960s of ''Rebel Worker'' by the

surrealists Franklin and

Penelope Rosemont. One edition was published in London with

Charles Radcliffe, who went on to become involved with the

Situationist International. By the 1980s, the ''Rebel Worker'' was being published as an official organ again, from the IWW's headquarters in Chicago, and the New York area was publishing a newsletter as well.

Return to workplace campaigns

Invigorated by the arrival of enthusiastic new members, the IWW began a wave of organizing drives. These largely took a regional form and they, as well as the union's overall membership, concentrated in Portland, Chicago, Ann Arbor, and throughout the state of California, which when combined accounted for over half of union drives from 1970 to 1979. In Portland, Oregon, the IWW led campaigns at Winter Products (a brass plating plant) in 1972, at a local

Winchell's Donuts (where a strike was waged and lost), at the Albina Day Care (where key union demands were won, including the firing of the director of the day care), of healthcare workers at

West Side School and the

Portland Medical Center, and of agricultural workers in 1974. The latter effort led to the opening of an IWW union hall in Portland to compete with extortionate hiring halls and day labor agencies. Organizing efforts led to a growth in membership, but repeated loss of strikes and organizing campaigns would anticipate the decline of the Portland branch after the mid-1970s, a stagnancy period which would last until the 1990s.

In California, union activities were based in

Santa Cruz, where in 1977 the IWW engaged in one of its most ambitious campaigns of the 1970s: an attempt in 1977 to organize 3,000 workers hired under the

Comprehensive Employment and Training Act

The Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA, ) was a United States federal law enacted by the Congress, and signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973 to train workers and provide them with jobs in the public service. ...

(CETA) in

Santa Cruz County. The campaign led to pay raises, the implementation of a grievance procedure, and medical and dental coverage, but the union failed to maintain its foothold, and in 1982 the CETA program would be replaced by the

Job Training Partnership Act

The Job Training Partnership Act of 1982 (JTPA, , , et seq.) was a United States federal law passed October 13, 1982, by Congress with regulations promulgated by the United States Department of Labor during the Ronald Reagan administration. The law ...

.

The IWW would win some lasting victories in Santa Cruz, however, with successful campaigns at the Janus Alcohol Recovery Center, the Santa Cruz Law Center, Project Hope, and the Santa Cruz Community Switchboard.

Elsewhere in California, the IWW was active in

Long Beach

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

in 1972, where it organized workers at

International Wood Products and

Park International Corporation (a manufacturer of plastic swimming pool filters) and went on strike after the firing of one worker for union-related activities.

Finally, in San Francisco, the IWW ran campaigns for radio station and food service workers.

In Chicago, the IWW was an early opponent of so-called

urban renewal

Urban renewal (also called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities. Urban renewal involves the clearing out of blighte ...

programs, and supported the creation of the "Chicago People's Park" in 1969. The Chicago branch also ran citywide campaigns for healthcare, food service, entertainment, construction, and metal workers, and its success with the latter led to an attempt to revive the national

Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union, which twenty years earlier had been a major component of the union. Metalworker organizing would largely end in 1978 after a failed strike at Mid-American Metal in

Virden, Illinois

Virden is a city in Macoupin and Sangamon counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. The population was 3,425 at the 2010 census, and 3,354 at a 2018 estimate.

The Macoupin County portion of Virden is part of the St. Louis, Missouri–Illinois ...

. The IWW also became one of the first unions to try to organize fast food workers, with an organizing campaign at a local

McDonald's

McDonald's Corporation is an American multinational fast food chain, founded in 1940 as a restaurant operated by Richard and Maurice McDonald, in San Bernardino, California, United States. They rechristened their business as a hambur ...

in 1973.

The IWW also built on its existing presence in Ann Arbor, which had existed since student organizing began at the University of Michigan, to launch an organizing campaign at the University Cellar, a college bookstore. The union won

National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an independent agency of the federal government of the United States with responsibilities for enforcing U.S. labor law in relation to collective bargaining and unfair labor practices. Under the Na ...

(NLRB) certification there in 1979 following a strike, and the store would become a strong job shop for the union until it was closed in 1986. The union launched a similar campaign at another local bookstore, Charing Cross Books, but was unable to maintain its foothold there despite reaching a settlement with management.

In the late 1970s, the IWW came to regional prominence in entertainment industry organizing, with an Entertainment Workers Organizing Committee being founded in Chicago in 1976, followed by campaigns organizing musicians in Cleveland in 1977 and Ann Arbor in 1978. The Chicago committee published a model contract which was distributed to musicians in the hopes of raising industry standards, as well as maintaining an active phone line for booking information. IWW musicians such as

Utah Phillips

Bruce Duncan "Utah" Phillips (May 15, 1935 – May 23, 2008)

, KVMR, Nevada City, California, May 24, 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008 ...

,

Faith Petric,

Bob Bovee, and

Jim Ringer

Jim or JIM may refer to:

* Jim (given name), a given name

* Jim, a diminutive form of the given name James

* Jim, a short form of the given name Jimmy

* OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism

* ''Jim'' (comics), a series by Jim Woodring

* ''Ji ...

also toured and promoted the union,

and in 1987 an anthology album, ''Rebel Voices'', was released.

Other IWW organizing campaigns of the 1970s included a

ShopRite supermarket in Milwaukee, at Coronet Foods in

Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Located almost entirely in Ohio County, of which it is the county seat, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and also contains a tiny portion extending ...

, chemical and fast food workers (including

KFC and

Roy Rogers

Roy Rogers (born Leonard Franklin Slye; November 5, 1911 – July 6, 1998) was an American singer, actor, and television host. Following early work under his given name, first as co-founder of the Sons of the Pioneers and then acting, the rebra ...

) in

State College, Pennsylvania

State College is a home rule municipality in Centre County in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is a college town, dominated economically, culturally and demographically by the presence of the University Park campus of the Pennsylvania Sta ...

, and hospital workers in Boston, all in 1973;

shipyards in

Houston, Texas, and restaurant workers in Pittsburgh in 1974; unsuccessful campaigns at the Prospect Nursing Home in

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston ...

, and a

Pizza Hut

Pizza Hut is an American multinational restaurant chain and international franchise founded in 1958 in Wichita, Kansas by Dan and Frank Carney. They serve their signature pan pizza and other dishes including pasta, breadsticks and dessert a ...

in

Arkadelphia, Arkansas

Arkadelphia is a city in Clark County, Arkansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 10,714. The city is the county seat of Clark County. It is situated at the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains. Two universities, Hender ...

, in 1975; and a construction workers organizing drive in

Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1978.

1990s

In the 1990s, the IWW was involved in many labor struggles and

free speech fights

Free speech fights are struggles over free speech, and especially those struggles which involved the Industrial Workers of the World and their attempts to gain awareness for labor issues by organizing workers and urging them to use their collective ...

, including

Redwood Summer Organized in 1990 by Earth First! and the Industrial Workers of the World, Redwood Summer was a three-month movement of environmental activism led by Judi Bari aimed at protecting old-growth redwood (''Sequoia sempervirens'') trees from logging by ...

, and the picketing of the Neptune Jade in the port of Oakland in late 1997.

In 1996, the IWW launched an organizing drive against

Borders Books in Philadelphia. In March, the union lost an NLRB certification vote by a narrow margin but continued to organize. In June, IWW member Miriam Fried was fired on trumped-up charges and a national boycott of Borders was launched in response. IWW members picketed at Borders stores nationwide, including Ann Arbor; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; Miami; Chicago; Palo Alto; Portland, OR; Portland, ME; Boston; Philadelphia; Albany; Richmond; St. Louis; Los Angeles; and other cities. This was followed up with a National Day of Action in 1997, where Borders stores were again picketed nationwide, and a second organizing campaign in London, England.

Also in 1996, the IWW began organizing at

Wherehouse Music in

El Cerrito, California

El Cerrito ( Spanish for "The Little Hill") is a city in Contra Costa County, California, United States, and forms part of the San Francisco Bay Area. It has a population of 25,962 according to the 2020 census. El Cerrito was founded by refugee ...

. The campaign continued until 1997, when management fired two organizers and laid off over half the employees, as well as reducing the hours of known union members. This directly affected the NLRB certification vote which followed, where the IWW lost over 2:1.

In 1998, the IWW chartered a San Francisco branch of the

Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), which trained hundreds of waterfront workers in health and safety techniques and attempted to institutionalize these safety practices on the San Francisco waterfront.

In 1999, the IWW chartered a local branch of the

Education Workers Industrial Union in

Boston, Massachusetts, which started to organize workers at local colleges and universities.

Additionally, IWW organizing drives in the late 90s included a strike at the Lincoln Park Mini Mart in Seattle in 1996, Keystone Job Corps, the community organization

ACORN, various homeless and youth centers in

Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the list of cities in Oregon, largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, Columbia rivers, Portland is ...

, sex industry workers, and recycling shops in

Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

. IWW members were also active in the building trades, shipyards, high tech industries, hotels and restaurants, public interest organizations, railroads, bike messengers, and lumber yards.

The IWW stepped in several times to help the rank and file in mainstream unions, including saw mill workers in

Fort Bragg in California in 1989, concession stand workers in the

San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

in the late 1990s, and shipyards along the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

.

2000–present

In the early 2000s, the IWW organized Stonemountain and Daughter Fabrics, a fabric shop in Berkeley, California. The shop continues to remain an IWW organized shop.

The city of Berkeley's recycling is picked up, sorted, processed and sent out all through two different IWW-organized enterprises.

In 2003, the IWW began organizing street people and other non-traditional occupations with the formation of the

Ottawa Panhandlers Union. A year later, the Panhandlers Union led a strike by the homeless. Negotiations with the city resulted in the city government promising to fund a newspaper written and sold by the homeless.

Between 2003 and 2006, the IWW organized unions at food co-operatives in Seattle, Washington and

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Pennsylvania. The IWW represents administrative and maintenance workers under contract in Seattle, while the union in Pittsburgh lost 22–21 in an NLRB election, only to have the results invalidated in late 2006, based on management's behavior before the election.

In 2004, an IWW union was organized in a New York City

Starbucks. In 2006, the IWW continued efforts at Starbucks by organizing several Chicago area shops.

In Chicago the IWW began an effort to organize

bicycle messengers.

In September 2004, IWW-organized short haul truck drivers in

Stockton,

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

walked off their jobs and went on a strike. Nearly all demands were met. Despite early victories in Stockton, the truck driver union ceased to exist in mid-2005.

In New York City, the IWW has organized immigrant foodstuffs workers since 2005. That summer, workers from Handyfat Trading joined the IWW, and were soon followed by workers from four more warehouses. Workers at these warehouses made gains such as receiving the

minimum wage and being paid overtime.

In 2006, the IWW moved its headquarters to

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wi ...

, and in 2010, headquarters was moved back to Chicago, Illinois.

Also in 2006, the IWW Bay Area Branch organized the Landmark Shattuck Cinemas. The Union had been negotiating for a contract with the goal of expanding

workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in various forms (examples include voting systems, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, systems of appeal) to the workplace. It can be implemented in a variety ...

.

In May 2007, the NYC warehouse workers came together with the

Starbucks Workers Union to form The Food and Allied Workers Union IU 460/640. In the summer of 2007, the IWW organized workers at two new warehouses: Flaum Appetizing, a

Kosher food distributor, and Wild Edibles, a seafood company. Over the course of 2007–08, workers at both shops were illegally terminated for their union activity. In 2008, the workers at Wild Edibles actively fought to get their jobs back and to secure overtime pay owed to them by the boss. In a workplace justice campaign called Focus on the Food Chain, carried out jointly with

Brandworkers International, the IWW workers won settlements against employers including Pur Pac, Flaum Appetizing and Wild Edibles.

Besides IWW's traditional practice of organizing industrially, the Union has been open to new methods such as organizing geographically: for instance, seeking to organize retail workers in a certain business district, as in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

.

The union has also participated in worker-related issues as protesting involvement in the war in Iraq, opposing sweatshops and supporting a boycott of

Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Originally marketed as a temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, it was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pemberton in Atlant ...

for that company's

support of the suppression of workers rights in

Colombia.

On July 5, 2008, the

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Grand Rapids is a city and county seat of Kent County in the U.S. state of Michigan. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 198,917 which ranks it as the second most-populated city in the state after Detroit. Grand Rapids is the ...

,

Starbucks Workers Union and

CNT-AIT in

Seville, Spain

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, organized a global day of action against alleged Starbucks

union busting