Independence from Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Previously, pressure had come from UKIP for the party to change its name and official tagline, 'UK Independence Now', believing it was a strategy to split their vote.Hope, Christopher Henley, Peter This, in addition to the use of 'An' at the beginning of the party name, placing them highest alphabetically on the

Previously, pressure had come from UKIP for the party to change its name and official tagline, 'UK Independence Now', believing it was a strategy to split their vote.Hope, Christopher Henley, Peter This, in addition to the use of 'An' at the beginning of the party name, placing them highest alphabetically on the

Independence from Europe's primary policy was to guarantee that the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU). This included its legal accessories, promising a withdrawal from the

Independence from Europe's primary policy was to guarantee that the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU). This included its legal accessories, promising a withdrawal from the

The party opposed government subsidy of

The party opposed government subsidy of

Independence from Europe was a minor, Eurosceptic political party in the

Before establishing the party, Mike Nattrass had long been involved with Britain's Eurosceptic movement. In 1994, Nattrass joined the right-wing

Before establishing the party, Mike Nattrass had long been involved with Britain's Eurosceptic movement. In 1994, Nattrass joined the right-wing

on 8 May and Nattrass' appearance on ''United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. The party was first registered in June 2012 but remained inactive until it was launched in October 2013 by sole party leader Mike Nattrass, a disaffected member of the UK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest par ...

(UKIP). It had no official political representation at the time of its dissolution in November 2017, but previously had one Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

(MEP) and three Councillors

A councillor is an elected representative for a local government council in some countries.

Canada

Due to the control that the provinces have over their municipal governments, terms that councillors serve vary from province to province. Unl ...

, all of whom were once members of UKIP.

Nattrass' deselection as a UKIP candidate in August 2013 saw him voluntarily leave the party and after deliberation, launch his own group whilst still an MEP. The party's name changed twice subsequently, largely due to the potential of voters mistaking it with UKIP; use of the word "Independence" in both parties' names proved particularly contentious, prompting two separate investigations by the Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

. Virtually all commentators dismissed the party as a means for disgruntled former UKIP members to confuse the electorate and split their previous party's support, an allegation Independence from Europe denied. This is despite the party costing UKIP between one and three seats at the 2014 European Parliament election

The 2014 European Parliament election was held in the European Union, from 22 to 25 May 2014.

It was the 8th parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979, and the first in which the European political parties fielded candid ...

, for which Nattrass' group is perhaps best known. Collecting 1.49% of the national vote, it proved to be their most successful election, although the party never had a candidate elected to any office.

It shared a similar right-wing policy platform with UKIP, with Nattrass stating as such amid the party's launch. Key policies included withdrawing the UK from the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

(EU), prioritising relations with the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

and introducing more stringent measures on immigration. It further supported widespread use of referendums

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, promoting English devolution and abolishing the National Assembly for Wales

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh Go ...

. Nattrass placed his party to the left of UKIP, however, due to both the party's general opposition to privatisation and its proposed nationalisation of targeted infrastructure and amenities.

History

Background and formation

Before establishing the party, Mike Nattrass had long been involved with Britain's Eurosceptic movement. In 1994, Nattrass joined the right-wing

Before establishing the party, Mike Nattrass had long been involved with Britain's Eurosceptic movement. In 1994, Nattrass joined the right-wing New Britain Party

New Britain was a minor British right-wing political party founded by Dennis Delderfield in 1976.Boothroyd, David, ''Politicos Guide to the History of British Political Parties'' (2001), p. 207. The party was de-registered in November 2008.

F ...

and unsuccessfully stood for the group in the Dudley West by-election of the same year. Alike most New Britain candidates, Nattrass was absorbed into and stood in Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

for the single-issue Referendum Party

The Referendum Party was a Eurosceptic, single-issue political party that was active in the United Kingdom from 1994 to 1997. The party's sole objective was for a referendum to be held on the nature of the UK's membership of the European Union ...

at the 1997 general election. Led by James Goldsmith

Sir James Michael Goldsmith (26 February 1933 – 18 July 1997) was a French-British financier, tycoon''Billionaire: The Life and Times of Sir James Goldsmith'' by Ivan Fallon and politician who was a member of the Goldsmith family.

His cont ...

, this party's policy was for a referendum to be held on the UK's relationship with the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

(EU), specifically as to whether the British population wanted to be part of a federal Europe or a free-trade bloc without wider political functions. Nattrass subsequently joined the UK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest par ...

(UKIP) and eventually rose to the positions of Party Chairman and Deputy Leader. As the UKIP candidate, he was elected as a representative for the West Midlands constituency in the 2004 European Parliament election

The 2004 European Parliament election was held between 10 and 13 June 2004 in the 25 member states of the European Union, using varying election days according to local custom. The European Parliamental parties could not be voted for, but electe ...

, and was re-elected in 2009.

Nattrass failed a candidacy assessment in August 2013 and was duly deselected as UKIP candidate for the 2014 election, prompting him to initiate unsuccessful legal action against the party.Walker, Jonathan He duly left UKIP and was in talks with the English Democrats

The English Democrats is a right-wing to far-right, English nationalist political party active in England. A minor party, it currently has no elected representatives at any level of UK government.

The English Democrats were established in 20 ...

, but cancelled plans to ally with them after they prematurely announced his joining the party. Nattrass, still a Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

(MEP), instead launched his own party after considering a career as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

. An Independence Party's creation was announced in October 2013,Edwards, Tom being renamed An Independence from Europe on 7 March 2014 to avoid confusion with UKIP. Nattrass had previously considered the label 4 A Referendum. Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

records show that he had registered his own party significantly earlier, on 20 June 2012. From this date, he had also been filing financial statements for the fledgling, albeit inactive, organisation. The new party's development benefited from an incident in September 2013 when a Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire an ...

lor, Chris Pain, was expelled from UKIP over an internal controversy. Fellow UKIP Councillors Alan Jesson and John Beaver supported Pain's innocence and were also expelled from the party for plotting to form a breakaway faction. All three became members of Nattrass' party and proceeded to represent their wards accordingly.

European Parliament election and controversy

An Independence from Europe fielded 60 candidates in the 2014 European Parliament election, proposing representatives for each of England's nine constituencies. The most notable of whom were Nattrass, who sought re-election in the West Midlands, and Laurence Stassen, a Dutch MEP who had recently left the Party for Freedom (PVV) and was vying for election in theSouth East England

South East England is one of the nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. It consists of the counties of Buckinghamshire, East Sussex, Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Kent, Oxfordshire, Berkshi ...

region. Stassen's unusual standing for the party "demonstrate the extent to which MEPs whose true ambition is to remain in the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

will go in order to remain in their seat" according to political scientist William T. Daniel. The party did not stand candidates in the Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

or Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

constituencies. Campaigning for the election included a nationwide party political broadcast

A party political broadcast (also known, in pre-election campaigning periods, as a party election broadcast) is a television or radio broadcast made by a political party.

In the United Kingdom the Communications Act 2003 prohibits (and previou ...

through the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Daily Politics

''Daily Politics'' was a BBC Television programme which aired between 6 January, 2003 and 24 July, 2018, presented by Andrew Neil and Jo Coburn. ''Daily Politics'' took an in-depth review of the daily events in both Westminster and other areas ...

'', where he was interviewed by Andrew Neil

Andrew Ferguson Neil (born 21 May 1949) is a Scottish former journalist and broadcaster who is chairman of ''The Spectator'' and presenter of '' The Andrew Neil Show'' on Channel 4. He was editor of ''The Sunday Times'' from 1983 to 1994. He f ...

on 14 May. Despite claiming it would receive more than 10% of the national vote and elect up to four MEPs, the party only collected 1.49% (235,124 ballots) and all candidates were defeated. Finishing seventh, it was the highest placed party not to elect an MEP; it polled more votes than the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP), which was defending two seats.

Previously, pressure had come from UKIP for the party to change its name and official tagline, 'UK Independence Now', believing it was a strategy to split their vote.Hope, Christopher Henley, Peter This, in addition to the use of 'An' at the beginning of the party name, placing them highest alphabetically on the

Previously, pressure had come from UKIP for the party to change its name and official tagline, 'UK Independence Now', believing it was a strategy to split their vote.Hope, Christopher Henley, Peter This, in addition to the use of 'An' at the beginning of the party name, placing them highest alphabetically on the ballot paper

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election and may be found as a piece of paper or a small ball used in secret voting. It was originally a small ball (see blackballing) used to record decisions made by voters in Italy around the 16t ...

, prompted an investigation by the Electoral Commission at the request of UKIP. Nattrass remarked "UKIP does not have sole right to the word independence" and the Commission soon dismissed the complaint. Notwithstanding, UKIP claimed the party's similar name unfairly cost them a seat in South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of the counties of Bristol, Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly), Dorset, Devon, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Cities ...

to the benefit of the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

, with Nattrass' group acquiring around 23,000 votes in the region. UKIP's then-leader Nigel Farage

Nigel Paul Farage (; born 3 April 1964) is a British broadcaster and former politician who was Leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) from 2006 to 2009 and 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Brexit Party (renamed Reform UK in 2021) from 2 ...

later complained " lowing Nattrass to launch a party with that name was shocking and showed the absolute contempt that the establishment have for us ... they were given the green light to dupe voters." Political scientists Matthew Goodwin

Matthew James Goodwin (born 17 December 1981) is a British academic who is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent. he is a commisioner of the Social Mobility Commission.

Early life ...

and Caitlin Milazzo concur, calling it "a deliberate attempt to confuse voters and damage Nattrass's old party."

The party's credibility was further attacked by commentators reporting the affair; Christopher Hope of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' dismissed the group as being "set up late last year to confuse voters who were trying to back Ukip". Journalist Donal Blaney further labelled them "hitherto unheard-of" outside the incident. Blaney also invokes Mike Smithson Mike Smithson may refer to:

* Mike Smithson (British journalist) (born 1946), British journalist, Liberal Democrat politician, and political betting expert

*Mike Smithson (Australian journalist), Australian news reporter

*Mike Smithson (baseball)

...

's opinion that if UKIP had acquired the minor party's overall vote share, it would have won two additional seats; Farage posited "some think it cost us three." In response to the incident, citing his deselection, Nattrass retorted " d arageexpect me just to melt away? No, I am going down with my flag." A second review by the Commission found the name was unsuitable and the party became Independence from Europe on 23 February 2015, in time for that year's general election.

Domestic elections and downfall

At the 2015 general election, the party contested five constituencies, despite previously indicating it would vie for ten. These were theLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

seats of Boston and Skegness and Brigg and Goole alongside the West Midlands seats of Meriden and Solihull; additionally contested was Cheadle, a constituency in Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester is a metropolitan county and combined authority area in North West England, with a population of 2.8 million; comprising ten metropolitan boroughs: Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Stockport, Tam ...

. Nattrass once again appeared on ''Daily Politics'', interviewed by Jo Coburn

Joanne Dawn Coburn (born 12 November 1967) is a British journalist with BBC News, a regular presenter of '' Politics Live'' (and formerly also '' Sunday Politics'' along with Andrew Neil) and previously had special responsibility for ''BBC Brea ...

on 1 April. No candidates were elected and the party accumulated a negligible vote share. Local elections

In many parts of the world, local elections take place to select office-holders in local government, such as mayors and councillors. Elections to positions within a city or town are often known as "municipal elections". Their form and conduct vary ...

in the same year saw the party unsuccessfully contest eight wards on East Lindsey District Council, with an additional candidate failing in his bid for election to Leicester City Council

Leicester City Council is a unitary authority responsible for local government in the city of Leicester, England. It consists of 54 councillors, representing 22 wards in the city, overseen by a directly elected mayor. It is currently control ...

. The following year's local elections saw the party field a candidate for Exeter City Council

Exeter City Council is the council and local government of the city of Exeter, Devon.

History

Proposed unitary authority status

The government proposed that the city should become an independent unitary authority within Devon, much like neighb ...

, who was comfortably defeated. A day later, the party contested a local by-election for Croydon London Borough Council

Croydon London Borough Council is the local authority for the London Borough of Croydon in Greater London, England. It is a London borough council, one of 32 in the United Kingdom capital of London. Croydon is divided into 28 wards, electing 70 c ...

triggered by the resignation of Emily Benn; the party finished second last, above Winston McKenzie

Winston Truman McKenzie (born 23 October 1953) is a British political activist and perennial candidate for public office. He is currently a founder and leader of the Unity in Action Party. He has been a member of every major UK political party, a ...

of the English Democrats. Independence from Europe failed to field any candidates in the 2017 local elections; incumbent Councillors Alan Jesson and John Beaver did not seek re-election and Chris Pain defected to the Lincolnshire Independents

Lincolnshire Independents is a British political party based in the county of Lincolnshire. They were founded in July 2008.

Local Government

At the 2009 election, Lincolnshire Independents stood 19 candidates for Lincolnshire County Council of ...

, leaving the party with no official political representation. The party did not contest any constituencies at the 2017 general election. It was "statutorily deregistered" by the Electoral Commission on 2 November of that year.

Ideology and policies

Little to no academic commentary has been conducted with regard to the party's ideology. Upon its launch in 2013, Nattrass implied "it will have similarright wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

ideals as UKIP", only to assert a year later that "we are not the same, we are to the left of UKIP." He subsequently repeated the line in 2015. Aside from any ideological reason, the party was founded out of a general disaffection with UKIP's management, particularly leader Nigel Farage and Party Chairman Steve Crowther, who left members feeling "dictated to". That said, the party stated in 2014 that some UKIP MEPs were frustrated at the party's 2009 effort in creating, and embracing, the Europe of Freedom and Democracy

Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) was a Eurosceptic political group in the European Parliament. The group was formed following the 2009 European parliamentary election, mostly composed of elements of the Independence/Democracy (IND/DEM) and ...

(EFD) group in the European Parliament. Right-wing populist

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establ ...

in ideology, Nattrass labelled EFD as "probably obnoxious" and temporarily left the group whilst an MEP. Despite calling Farage a "totalitarian", Nattrass maintained "I support the principles UKIP stands for" whilst protesting his deselection in court. The party claimed to advocate a society comprising " rsonal freedom with personal responsibility", supported by what it saw as "traditional commonsense policies".

Constitutional and legislative policy

Independence from Europe's primary policy was to guarantee that the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU). This included its legal accessories, promising a withdrawal from the

Independence from Europe's primary policy was to guarantee that the United Kingdom left the European Union (EU). This included its legal accessories, promising a withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

(ECHR). The party advocated the increased use of direct democracy, namely through referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

s. Petitions with support from more than 5% of the electorate would trigger a national referendum on a respective issue, with the outcome legally binding by default. Conversely, Nattrass stated in 2014 that his party was averse to the idea of a nationwide vote on the UK's membership of the EU, calling for "MPs with backbone" to ensure a departure was delivered.

The party advocated sweeping reforms of the UK's legislative process. These included a reduction of the number of Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MPs) in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

by one third (650 to 430) and the replacement of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

with an elected upper chamber. Scheduled debates would have been introduced, upon which members for Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh constituencies would return to their devolved legislatures, leaving the UK Parliament to discuss English affairs exclusively. The party repeatedly advocated the abolition of the National Assembly for Wales

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh Go ...

, however, at one time adopting the tagline 'Abolish Assembly and leave European Union'; it suggested a referendum be held in Wales over the matter. Devolved legislatures' membership would have no longer consisted of politicians elected specifically to those chambers (i.e. MLAs, MSPs

Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP; gd, Ball Pàrlamaid na h-Alba, BPA; sco, Memmer o the Scots Pairliament, MSP) is the title given to any one of the 129 individuals elected to serve in the Scottish Parliament.

Electoral system

The ad ...

or AMs), but would have instead comprised those UK MPs returning routinely from the national parliament.

On an individual basis, MPs would have been paid and claimed expenses in-line with existing British civil service guidelines. If elected, the party claimed it would " ild a condominium to house MP's whilst they reside in London" and scrap their second home allowances. Legislators would have been accountable by way of an 'Independent Politicians Complaints Commission', with its members chosen by designated non-governmental organisations

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in ...

(NGOs). Furthermore, the activities of political parties would have faced greater regulation; whips

A whip is a tool or weapon designed to strike humans or other animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain. They can also be used without inflicting pain, for audiovisual cues, such as in equestrianism. They are generally ...

would have been removed from the select committee appointment process and party sanctioning against rebellious MPs disallowed.

Economic policy

The party claimed that by disowning tariffs and restrictions imposed by theEuropean Union Customs Union

The European Union Customs Union (EUCU), formally known as the Community Customs Union, is a customs union which consists of all the member states of the European Union (EU), Monaco, and the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekel ...

(EUCU) the UK could focus on adopting amicable free trade with the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

. The party would have further sought to reduce unemployment by limiting the proportion of migrant work imported from EU member states, as well as attempted to lower Council Tax

Council Tax is a local taxation system used in England, Scotland and Wales. It is a tax on domestic property, which was introduced in 1993 by the Local Government Finance Act 1992, replacing the short-lived Community Charge, which in turn re ...

by scrapping the fiscal implications of the union's Landfill Directive

The Landfill Directive, more formally Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 is a European Union directive that regulates waste management of landfills in the European Union. It was implemented by its Member States by 16 July 2001.

The D ...

. Independence from Europe claimed that by abandoning the EU, and thus the cost of membership, the UK's national debt could have been cleared. Domestic budgetary policies included the raising of personal allowance

In the UK tax system, personal allowance is the threshold above which income tax is levied on an individual's income. A person who receives less than their own personal allowance in taxable income (such as earnings and some benefits) in a give ...

to £15,000, broad simplification of both personal

Personal may refer to:

Aspects of persons' respective individualities

* Privacy

* Personality

* Personal, personal advertisement, variety of classified advertisement used to find romance or friendship

Companies

* Personal, Inc., a Washington, ...

and corporate

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and r ...

tax and opposition to zero-hours contracts. In addition, the party condoned the forced collection of tax from evaders and the nationalisation of private finance initiatives (PFIs).

Energy, environment and transport policy

The party opposed government subsidy of

The party opposed government subsidy of wind turbine

A wind turbine is a device that converts the kinetic energy of wind into electrical energy. Hundreds of thousands of large turbines, in installations known as wind farms, now generate over 650 gigawatts of power, with 60 GW added each yea ...

s and instead proposed the increased use of clean coal technology

Coal pollution mitigation, sometimes called clean coal, is a series of systems and technologies that seek to mitigate the health and environmental impact of coal; in particular air pollution from coal-fired power stations, and from coal burnt b ...

and nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles ( neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manife ...

to address the UK's energy shortage. This would have been accompanied by a state-owned 'Public British Energy Company', a measure that the party hoped would keep consumer costs affordable. The party would also have abandoned catch quotas set by the EU's Common Fisheries Policy and established 'no fishing zones' to ensure plentiful stocks.

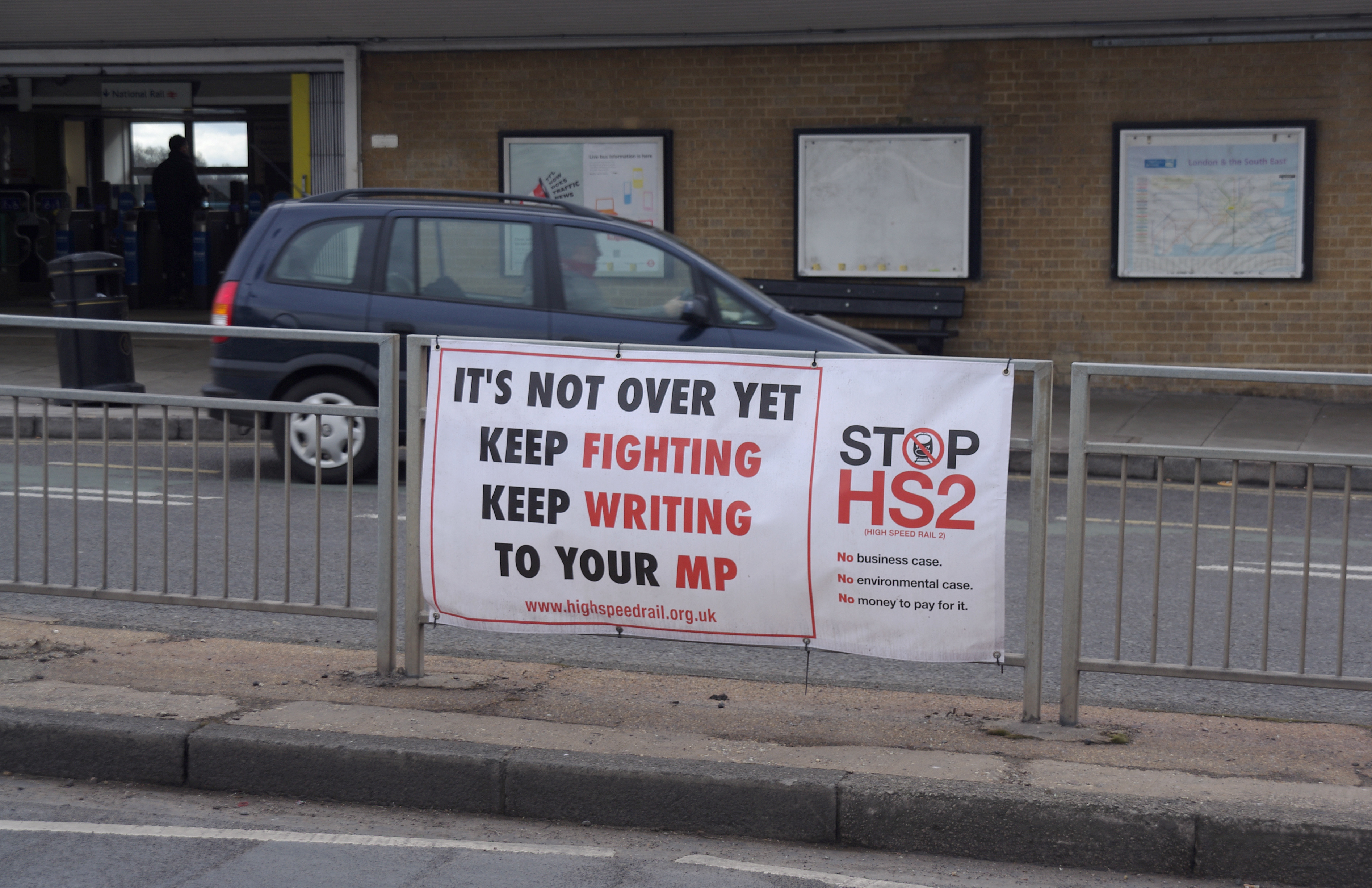

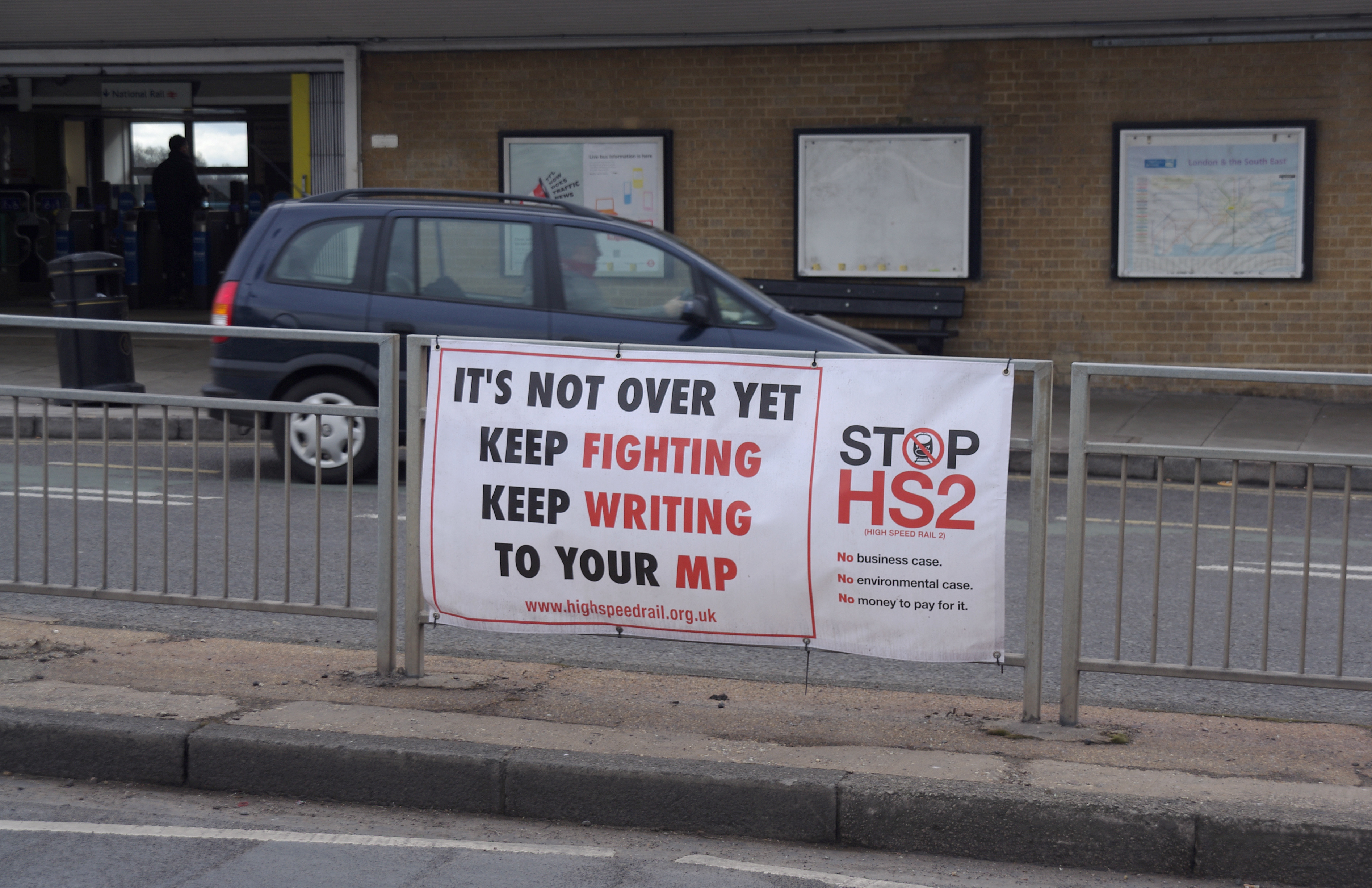

In transport policy, Independence from Europe was generally skeptical of large-scale developments. BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

characterised the group's opposition to the construction of the High Speed 2

High Speed 2 (HS2) is a planned high-speed railway line in England, the first phase of which is under construction in stages and due for completion between 2029 and 2033, depending on approval for later stages. The new line will run from its m ...

(HS2) railway as among " s key policies"; the group further warned against expansion of London's Standsted and Gatwick

Gatwick Airport (), also known as London Gatwick , is a major international airport near Crawley, West Sussex, England, south of Central London. In 2021, Gatwick was the third-busiest airport by total passenger traffic in the UK, after H ...

airports, as well as the introduction of a third runway at Heathrow

Heathrow Airport (), called ''London Airport'' until 1966 and now known as London Heathrow , is a major international airport in London, England. It is the largest of the six international airports in the London airport system (the others bei ...

. Furthermore, the party sought to abolish toll roads

A toll road, also known as a turnpike or tollway, is a public or private road (almost always a controlled-access highway in the present day) for which a fee (or '' toll'') is assessed for passage. It is a form of road pricing typically implemente ...

and nationalise UK railway franchises "if they fail din viability or in their contractual obligations."

Foreign, defence and immigration policy

The group sought to re-establish "traditional links" with the Commonwealth of Nations, believing that the UK had "lost invaluable trading links, respect and friendship" with the organisation since joining the EU. Independence from Europe twice asserted that the UK misspends foreign aid on countries wealthy enough to fund independentspace programs

This is a list of government agencies engaged in activities related to outer space and space exploration.

As of 2022, 77 different government space agencies are in existence, 16 of which have launch capabilities. Six government space agencies ...

, it suggested such funding should be diverted to support Britain's elderly population. In defence policy, the party pledged to increase the number of armed forces personnel to 200,000 and reduce the number of British troops sent to fight abroad, further encouraging the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

(UN) to take more responsibility over international security.

Independence from Europe called for stricter immigration policy to be implemented in the UK, but refused to set a statistical migration target. It supported an 'Australian-style' points-based system to regulate immigration once the UK had left the European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade As ...

(EEA), citing pressures on population growth, housing and infrastructure. Foreigners would also have faced more stringent rules once they had arrived; temporary visitors would have had to carry identification at all times, as well as resided in the UK for at least 10 years before becoming eligible for British citizenship. Such measures, the party hoped, would justify the reintroduction of the country's work permit scheme.

Social policy

The party supported the maintenance of Britain'sNational Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

(NHS) to be free at the point of delivery and described itself as "dead against privatisation" of the institution. Whilst reducing bureaucracy in the NHS, the party would also have aimed to invest a further £5 billion to train 40,000 more nurses in addition to 10,000 extra doctors. Free dental and eye treatment would have been restored and foreign visitors would be required to possess private medical insurance

Health insurance or medical insurance (also known as medical aid in South Africa) is a type of insurance that covers the whole or a part of the risk of a person incurring medical expenses. As with other types of insurance, risk is shared among ma ...

during their time in the UK. It sought to return more community services, like the NHS, into public ownership where they had been privatised entirely or in-part, including prisons and the Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional ser ...

. It would have reserved the UK's wider welfare system to cater exclusively for British citizens; they would also have limited the amount of tax credit

A tax credit is a tax incentive which allows certain taxpayers to subtract the amount of the credit they have accrued from the total they owe the state. It may also be a credit granted in recognition of taxes already paid or a form of state "dis ...

s a childless, able-bodied citizen could receive to 80% of the weekly national minimum wage

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 creates a minimum wage across the United Kingdom.. E McGaughey, ''A Casebook on Labour Law'' (Hart 2019) ch 6(1) From 1 April 2022 this was £9.50 for people age 23 and over, £9.18 for 21- to 22-year-olds, £6 ...

as well as restricted child benefit

Child benefit or children's allowance is a social security payment which is distributed to the parents or guardians of children, teenagers and in some cases, young adult (psychology), young adults. A number of countries operate different versions o ...

payments for households with more than two juveniles and/or a combined annual income of over £50,000. Independence from Europe supported and sought to extend tenants' 'Right to Buy

The Right to Buy scheme is a policy in the United Kingdom, with the exception of Scotland since 1 August 2016 and Wales from 26 January 2019, which gives secure tenants of councils and some housing associations the legal right to buy, at a large ...

' council and housing association

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, housing associations are private, Non-profit organization, non-profit making organisations that provide low-cost "Public housing in the United Kingdom, social housing" for people in need of a home. Any budge ...

properties.

To address crime, the party sought to deport foreign offenders, extend neighborhood watch schemes and hold a referendum on restoring capital punishment in the UK

Capital punishment in the United Kingdom predates the formation of the UK, having been used within the British Isles from ancient times until the second half of the 20th century. The last executions in the United Kingdom were by hanging, and t ...

. It further pledged to invest £2.5 billion into the police service, promising to recruit 10,000 more officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

. In addition, the group would have reformed education policy by aiming to cut school class sizes and scrapping tuition fees

Tuition payments, usually known as tuition in American English and as tuition fees in Commonwealth English, are fees charged by education institutions for instruction or other services. Besides public spending (by governments and other public bo ...

for UK students attending British universities

Universities in the United Kingdom have generally been instituted by royal charter, papal bull, Act of Parliament, or an instrument of government under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 or the Higher Education and Research Act 2017. D ...

; conversely, all foreign students would have been required to pay in full.

See also

* Independence from Europe election resultsReferences

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * {{Portal bar, Politics, United Kingdom, Conservatism, European Union 2012 establishments in the United Kingdom 2017 disestablishments in the United Kingdom Eurosceptic parties in the United Kingdom Naming controversies Organisations based in the West Midlands (county) Political parties established in 2012 Political parties disestablished in 2017 UK Independence Party breakaway groups