Impeachment of Warren Hastings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first

Hastings soon ran into opposition on the Council. His principal enemy was the Irish-born politician Philip Francis. Francis developed a strong dislike of Hastings and was convinced that the Governor General's policies were self-serving and destructive. This was a belief shared with some other members of the Council whom he was able to influence. Francis and Hastings' personal rivalry continued for many years and led to a duel between them in 1780 in which Francis was wounded, but not killed. Francis returned to Britain in 1781 and began raising questions about Hastings' conduct. He found support from many leading opposition Whigs.

In 1780

Hastings soon ran into opposition on the Council. His principal enemy was the Irish-born politician Philip Francis. Francis developed a strong dislike of Hastings and was convinced that the Governor General's policies were self-serving and destructive. This was a belief shared with some other members of the Council whom he was able to influence. Francis and Hastings' personal rivalry continued for many years and led to a duel between them in 1780 in which Francis was wounded, but not killed. Francis returned to Britain in 1781 and began raising questions about Hastings' conduct. He found support from many leading opposition Whigs.

In 1780

/ref> While Burke took the proceedings very seriously, Macaulay tells us that many spectators treated the trial as a social event. Hastings himself remarked that “for the first half hour, I looked up to the orator in a reverie of wonder, and during that time I felt myself the most culpable man on earth.” Hastings was granted

In spite of the early excitement about the trial public interest in it began to wane as it dragged on over months and years. Other major events dominated the news particularly once the

In spite of the early excitement about the trial public interest in it began to wane as it dragged on over months and years. Other major events dominated the news particularly once the

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, was attempted between 1787 and 1795 in the Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

. Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

was accused of misconduct during his time in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, particularly relating to mismanagement and personal corruption. The impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

prosecution was led by Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

and became a wider debate about the role of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

and the expanding empire in India. According to historian Mithi Mukherjee, the impeachment trial became the site of a debate between two radically opposed visions of empire—one represented by Hastings, based on ideas of absolute power and conquest in pursuit of the exclusive national interests of the colonizer, versus one represented by Burke, of sovereignty based on a recognition of the rights of the colonized.

The trial did not sit continuously and the case dragged on for seven years. When the eventual verdict was given Hastings was overwhelmingly acquitted. It has been described as "probably the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

' most famous, certainly the longest, political trial".

Background

Appointment

Born in 1732, Warren Hastings spent much of his adult life inIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

after first travelling out as a clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service ...

of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

in 1750. Hastings developed a reputation as an "Indian" who sought to use traditional Indian methods of governance to run British India rather than the policy of importing European-style law, government and culture favoured by many of his colleagues and representatives of other colonial powers in India. After working his way through the ranks of the Company he was appointed in 1773 as governor general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

, a new position that had been created by the North government in order to improve the running of British India. The old structure of rule had come under strain as the Company's holdings had expanded in recent decades from isolated trading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically the location of the trading post would allow people from one geographic area to tr ...

s to large swathes of territory and population.

The powers of the governor general were balanced out by the establishment of a Calcutta Council

The Supreme Council of Bengal was the highest level of executive government in British India from 1774 until 1833: the period in which the East India Company, a private company, exercised political control of British colonies in India. It was for ...

which had the authority to veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

his decisions. Hastings spent much of his time in office marshalling his own supporters on the Council in an effort to avoid being outvoted.

Disputes and war

Hastings soon ran into opposition on the Council. His principal enemy was the Irish-born politician Philip Francis. Francis developed a strong dislike of Hastings and was convinced that the Governor General's policies were self-serving and destructive. This was a belief shared with some other members of the Council whom he was able to influence. Francis and Hastings' personal rivalry continued for many years and led to a duel between them in 1780 in which Francis was wounded, but not killed. Francis returned to Britain in 1781 and began raising questions about Hastings' conduct. He found support from many leading opposition Whigs.

In 1780

Hastings soon ran into opposition on the Council. His principal enemy was the Irish-born politician Philip Francis. Francis developed a strong dislike of Hastings and was convinced that the Governor General's policies were self-serving and destructive. This was a belief shared with some other members of the Council whom he was able to influence. Francis and Hastings' personal rivalry continued for many years and led to a duel between them in 1780 in which Francis was wounded, but not killed. Francis returned to Britain in 1781 and began raising questions about Hastings' conduct. He found support from many leading opposition Whigs.

In 1780 Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali ( حیدر علی, ''Haidarālī''; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the att ...

, the ruler of Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude o ...

, went to war with the company after British forces captured the French-controlled port of Mahé. Taking advantage of Britain's involvement in the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

and the support of French forces Hyder went on the offensive and enjoyed success during the opening stages of the war, inflicting a serious defeat at the Battle of Pollilur

The Battle of Pollilur (a.k.a. Pullalur), also known as the Battle of Polilore or Battle of Perambakam, took place on 10 September 1780 at Pollilur near Conjeevaram, the city of Kanchipuram in present-day Tamil Nadu state, India, as part of th ...

and at one point threatening Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

itself with capture. The Commander in Chief Eyre Coote Eyre Coote may refer to:

*Eyre Coote (East India Company officer) (1726–1783), Irish soldier and Commander-in-chief of India

*Eyre Coote (British Army officer) (1762–1823), Irish-born general in the British Army

* Eyre Coote (MP) (1806–1834), ...

went south with reinforcements and defeated Hyder's army in a series of battles which helped to steady the position in the Carnatic. Hyder was unable to secure victory and the war ended in a stalemate

Stalemate is a situation in the game of chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the infer ...

. It was halted by the Treaty of Mangalore

The Treaty of Mangalore was signed between Tipu Sultan and the British East India Company on 11 March 1784. It was signed in Mangalore and brought an end to the Second Anglo-Mysore War.

Background

Hyder Ali became dalwai Dalavayi of Mysore by ...

in 1784 which largely restored the status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When use ...

. Even so, the British position in India had been severely threatened.

The war shook public confidence and raised questions about the supposed mismanagement by the Company's agents in India. It proved to be a catalyst for the growing campaign in London against Hastings which gathered strength during the ensuing years.

First attacks

The Company had already gone through scandals in the 1760s and 1770s and the wealthy nabobs who returned to Britain from India were widely unpopular. Against this backdrop the criticisms circulated by Francis and others provoked a general consensus that the 1773 India Act had not been sufficient to rein in the alleged excesses. The Indian question again became a contentious political issue. TheFox–North Coalition

The Fox–North coalition was a government in Great Britain that held office during 1783.Chris Cook and John Stevenson, ''British Historical Facts 1760–1830'', Macmillan, 1980 As the name suggests, the ministry was a coalition of the groups s ...

fell from power after it attempted to bring in a radical East India Bill in 1783. The following year the new government of William Pitt passed an India Act of 1784 which established a Board of Control and which finally stabilised the governance of India.

Hastings was personally attacked by Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

during the presentation of his India Bill. When Pitt introduced his Bill he failed to mention Hastings at all, seen as expressing a lack of confidence, and made wide-ranging criticisms of the Company. He suggested that recent wars in India had been ruinous and unnecessary. Hastings was particularly upset by this, as he was an admirer of Pitt. By now, Hastings wished to resign and return home unless the role of Governor General was given greater freedom to exercise power—which was unlikely to be granted him. He handed over to an Acting Governor General, John MacPherson until a permanent replacement was appointed.

Return to Britain

Surender Hastings sailed for home on 6 February and reached Britain in June 1785. During the voyage he wrote a defence of his conduct ''The State of Bengal'' and presented it to Henry Dundas. Hastings anticipated he would face attacks in Parliament and the press but expected them to be short-lived and to fall away once he was there in person to defend himself. Initially this proved to be the case as he enjoyed an audience with KingGeorge III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

and a unanimous vote of thanks by the directors of the East India Company. Hastings even hoped to be awarded an Irish peerage

The Peerage of Ireland consists of those titles of nobility created by the English monarchs in their capacity as Lord or King of Ireland, or later by monarchs of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It is one of the five di ...

. However, in Parliament Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

announced he "would at a future date make a motion respecting the conduct of a gentleman just returned from India".

In early 1786 Burke began his first move by raising questions over Hastings' role in the Maratha War. The attacks on Hastings were largely made by opposition Whigs hoping to embarrass the government of William Pitt. Pitt and other government ministers such as Dundas defended Hastings and suggested that he had saved the British Empire in Asia. Philip Francis made eleven specific charges against Hastings, and others later followed. They covered various subjects such as the Rohilla War

The First Rohilla War of 1773–1774 was a punitive campaign by Shuja-ud-Daula, Nawab of Awadh on the behalf of Mughal Emperor, against the Rohillas, Afghan highlanders settled in Rohilkhand, northern India. The Nawab was supported by troops ...

, execution of Nanda-Kumar and Hastings' treatment of the Rajas of Benares Chait Singh. Pitt broadly defended Hastings, but declared his punishment of the Rajah had been excessive. In the wake of this an anti-Hastings motion was passed in the Commons 119–79.

Encouraged by Pitt's failure to adequately support Hastings, his opponents pressed on with their campaign. The situation quickly deteriorated for Hastings. It soon became clear that he was heading towards an impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

. Hastings recruited Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough

Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough, (16 November 1750 – 13 December 1818), was an English judge. After serving as a member of parliament and Attorney General, he became Lord Chief Justice.

Early life

Law was born at Great Salkeld, in Cum ...

to act in his defence. On 21 May 1787 Hastings was arrested by the Serjeant-at-Arms

A serjeant-at-arms, or sergeant-at-arms, is an officer appointed by a deliberative body, usually a legislature, to keep order during its meetings. The word "serjeant" is derived from the Latin ''serviens'', which means "servant". Historically, ...

and taken to the House of Lords to hear the charges against him.

Hastings was to be prosecuted in the House of Lords by an Impeachment Committee. Impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

was a relatively rare process of prosecuting those in high public office. Previous figures who had faced such trials included the Duke of Buckingham, a favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated s ...

of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, and the Earl of Strafford, whose impeachment failed (but was followed up by a legislative bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder or writ of attainder or bill of penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and punishing them, often without a trial. As with attai ...

that resulted in Strafford's execution).

Impeachment

Opening

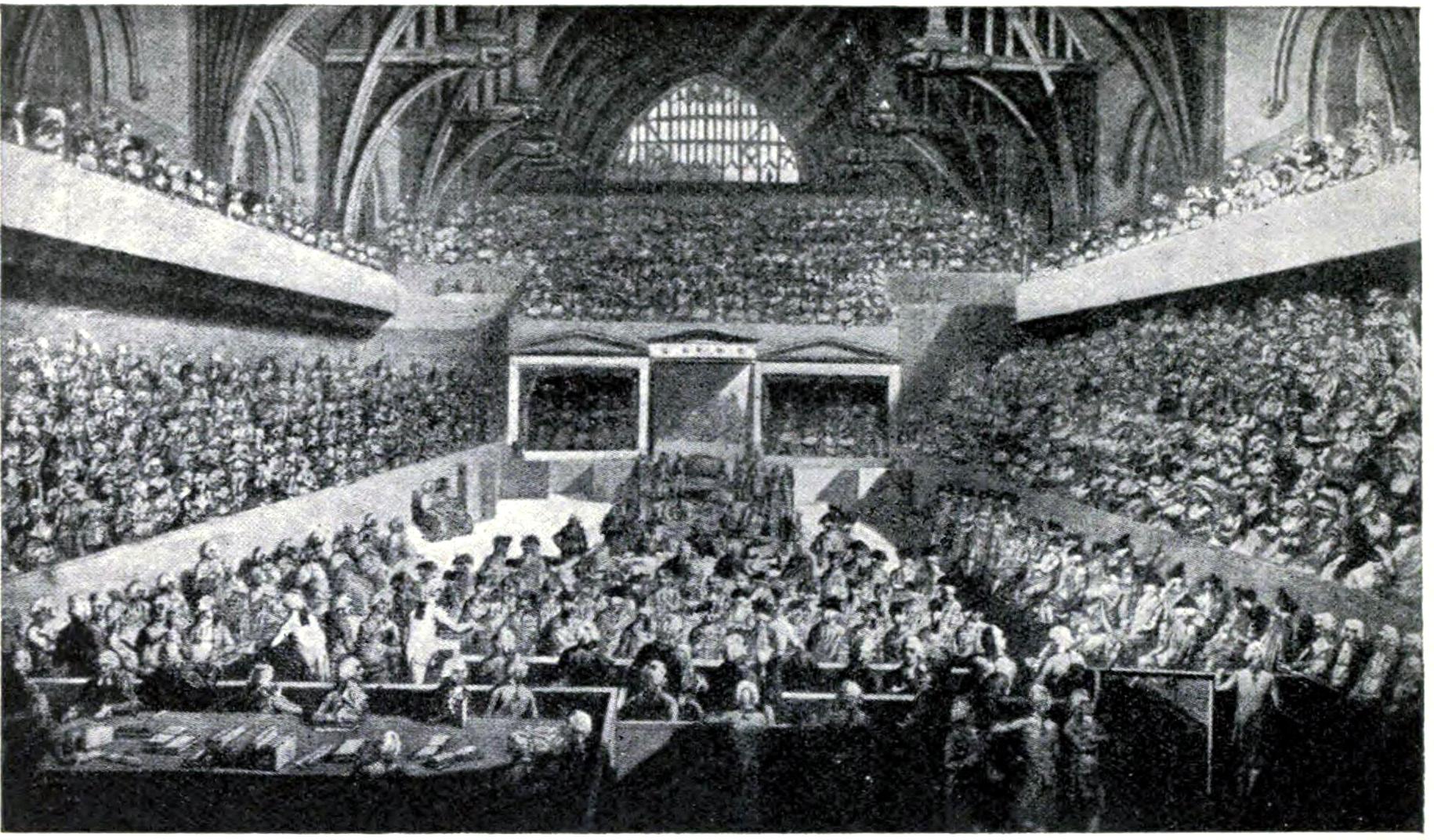

Hastings' trial began on 13 February 1788. It took place inWestminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, with members of the House of Commons seated to Hastings' right, the Lords to his left, and a large audience of spectators, including royalty, in the boxes and public galleries. The proceedings began with a lengthy address by Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

, who took four days to cover all the charges against Hastings.The World’s Famous Orations. Ireland (1775–1902). "III. At the Trial of Warren Hastings" Edmund Burke (1729–97)/ref> While Burke took the proceedings very seriously, Macaulay tells us that many spectators treated the trial as a social event. Hastings himself remarked that “for the first half hour, I looked up to the orator in a reverie of wonder, and during that time I felt myself the most culpable man on earth.” Hastings was granted

bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

in spite of Burke's suggestion that he might flee the country with the wealth he had allegedly stolen from India. Further speeches were made over the coming weeks by other leading Whigs such as Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Irish satirist, a politician, a playwright, poet, and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He is known for his plays such as '' The Rivals'', ''The ...

and Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

. In total there were nineteen members of the Impeachment Committee.

Public opinion changes

In spite of the early excitement about the trial public interest in it began to wane as it dragged on over months and years. Other major events dominated the news particularly once the

In spite of the early excitement about the trial public interest in it began to wane as it dragged on over months and years. Other major events dominated the news particularly once the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

began in 1789. Sheridan now complained he was "heartily tired of the Hastings trial" despite being one of its instigators.Garrard & Newell p. 138 As the trial progressed, public attitudes about Hastings also began to shift. Hastings had initially been overwhelmingly portrayed as guilty in the popular press, but doubts were increasingly raised. Increased support for Hastings may have been a result of declining perceptions of his accusers. In a cartoon James Gillray

James Gillray (13 August 1756Gillray, James and Draper Hill (1966). ''Fashionable contrasts''. Phaidon. p. 8.Baptism register for Fetter Lane (Moravian) confirms birth as 13 August 1756, baptism 17 August 1756 1June 1815) was a British caricatur ...

portrayed Hastings as the "Saviour of India" being assaulted by bandits resembling Burke and Fox.

A major lift for the defence came with the testimony on 9 April 1794 of Lord Cornwallis who had recently returned from India, where he succeeded Hastings as Governor General. Cornwallis rejected the accusations that Hastings' actions had damaged Britain's reputation and observed that Hastings was universally popular with the inhabitants. When asked if he had "found any just cause to impeach the character of Mr Hastings?" he replied "never".

A further blow for the prosecution came with the evidence of William Larkins the former Accountant General of Bengal. They had rested their hopes on his revealing widespread corruption but he denied that Hastings had amassed any illicit money and made a defence of his conduct. Various other figures came forwards as character witnesses to support Hastings. Burke's reply to the defence lasted nine days from late May to mid-June 1794.

Verdict

On 23 April 1795 theLord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

Lord Loughborough oversaw the delivery of the verdict

In law, a verdict is the formal finding of fact made by a jury on matters or questions submitted to the jury by a judge. In a bench trial, the judge's decision near the end of the trial is simply referred to as a finding. In England and Wales ...

. A third of the Lords who had attended the trial's opening had since died and only twenty-nine of the others had sat through enough of the evidence to be permitted to pronounce judgement. Loughborough asked each of the peers sixteen questions relating to individual charges. On most charges he was unanimously found not guilty. On three questions five or six peers gave guilty verdicts, but Hastings was still comfortably cleared by majority vote

A majority, also called a simple majority or absolute majority to distinguish it from related terms, is more than half of the total.Dictionary definitions of ''majority'' aMerriam-Webster

online

Also see Mukherjee,

India in the Shadows of Empire: A Legal and Political History

' (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010). * Brian Smith. "Edmund Burke, the Warren Hastings trial, and the moral dimension of corruption." ''Polity'' 40.1 (2008): 70-9

online

* * *

Aftermath

Hastings was financially ruined by the impeachment and was left with debts of £70,000. Unlike many other Indian officials he had not amassed a large fortune while in India and he had to fund his legal defence, which had cost an estimated £71,000, out of his own funds. His defence lawyer was Richard Shaw(e) who built his mansion Casino House inHerne Hill

Herne Hill is a district in South London, approximately four miles from Charing Cross and bordered by Brixton, Camberwell, Dulwich, and Tulse Hill. It sits to the north and east of Brockwell Park and straddles the boundary between the borough ...

at least in part from the proceeds, employing John Nash and Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton (21 April 1752 – 24 March 1818) was the last great English landscape designer of the eighteenth century, often regarded as the successor to Capability Brown; he also sowed the seeds of the more intricate and eclectic styles of ...

as landscape designer (responsible for the water garden the remnants of which survived as Sunray Gardens in 2012).

Meanwhile, Hastings appealed to the British government for financial assistance and was eventually compensated by the East India Company with a loan of £50,000 and a pension of £4,000 a year.

Although this did not solve all his financial worries, Hastings was ultimately able to fulfill his lifelong ambition of purchasing the family's traditional estate of Daylesford in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

which had been lost in a previous generation. Hastings held no further public office, but was regarded as an expert on Indian matters and was asked to give evidence to parliament on the subject in 1812. After he had finished giving his testimony, the members all stood up in an almost unprecedented act for anyone other than the royal family.

Hastings' successors as Governor General, beginning with Lord Cornwallis, were granted the much wider powers that Hastings had sought while in Calcutta. Pitt's India Act served to move much of the supervisory role for India away from the East India Company directors and officials in Leadenhall Street

__NOTOC__

Leadenhall Street () is a street in the City of London. It is about and links Cornhill in the west to Aldgate in the east. It was formerly the start of the A11 road from London to Norwich, but that route now starts further east at ...

to a new political Board of Control based in London.

The overwhelming failure to secure a conviction, and the stream of testimony that came out of India praising him, have led commentators to ask why Hastings, who appeared to many observers to have given dedicated service to the company and to have curbed its worst excesses, ended up being prosecuted in the first place. A number of factors may have played a part, including partisan politics, although Pitt joined the opposition in supporting the Impeachment.

There has been particular focus on the role played by Pitt—particularly his sudden withdrawal of outright support for Hastings in 1786 which galvanised the opposition into pursuing the case. It is possible that Pitt believed "he ran the very genuine risk of being accused by the opposition of shielding a notorious criminal from justice, for political reasons". Henry Dundas was himself later impeached

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

in 1806 and acquitted in the final ever impeachment in Britain.

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * Mukherjee, Mithi. "Justice, War, and the Imperium: India and Britain in Edmund Burke's Prosecutorial Speeches in the Impeachment Trial of Warren Hastings." ''Law and History Review'' 23.3 (2005): 589-63online

Also see Mukherjee,

India in the Shadows of Empire: A Legal and Political History

' (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010). * Brian Smith. "Edmund Burke, the Warren Hastings trial, and the moral dimension of corruption." ''Polity'' 40.1 (2008): 70-9

online

* * *

Sources

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hastings, Warren Hastings, Warren Impeachment Hastings, Warren Impeachment Hastings, Warren Hastings, Warren Impeachment Hastings, Warren Impeachment Hastings, Warren Impeachment Hastings, Warren