Idaho v. United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Idaho v. United States'', 533 U.S. 262 (2001), was a

In the Supreme Court,

In the Supreme Court,

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case in which the Court held that the United States, not the state of Idaho, held title to lands submerged under Lake Coeur d'Alene

Lake Coeur d'Alene, officially Coeur d'Alene Lake ( ), is a natural dam-controlled lake in North Idaho, located in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. At its northern end is the city of Coeur d'Alene. It spans in length and rang ...

and the St. Joe River

The Saint Joe River (sometimes abbreviated St. Joe River) is a long tributary of Coeur d'Alene Lake in northern Idaho. Beginning at an elevation of in the Northern Bitterroot Range of eastern Shoshone County, it flows generally west through t ...

, and that the land was held in trust for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe

The Coeur d'Alene (also ''Skitswish''; natively ''Schi̲tsu'umsh'') are a Native American nation and one of five federally recognized tribes in the state of Idaho.

The Coeur d'Alene have sovereign control of their Coeur d'Alene Reservation, ...

as part of its reservation, and in recognition (established in the 19th century) of the importance of traditional tribal uses of these areas for basic food and other needs.

Background

History

TheCoeur d'Alene Tribe

The Coeur d'Alene (also ''Skitswish''; natively ''Schi̲tsu'umsh'') are a Native American nation and one of five federally recognized tribes in the state of Idaho.

The Coeur d'Alene have sovereign control of their Coeur d'Alene Reservation, ...

is an Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

tribe in northern Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

. The Coeur d'Alene people once inhabited in northern Idaho, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, and Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, but today, the only land controlled by the tribal nation is the Coeur d'Alene Reservation in Benewah and Kootenai counties, Idaho.

In 1853, the territorial governor of Washington (which at the time included the panhandle of Idaho), Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

, began to negotiate treaties with local tribes. By 1855, Stevens had treaties with most of the tribes in the area, but not including the Coeur d'Alene tribe. At the same time, gold had been discovered near Fort Colvile

The trade center Fort Colvile (also Fort Colville) was built by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River in 1825 and operated in the Columbia fur district of the company. Named for Andrew Colvile,Lewis, S. William. ' ...

and on the Yakima reservation. By September 1853, Yakima Indians killed six prospectors in retaliation for attacks on the tribes by trespassing miners. Stevens negotiated a fragile peace in 1856, but the U.S. Army was unable to keep prospectors out of Indian lands. By 1858 hostilities sparked again.

In May 1858, Colonel Steptoe led a group of about 130 dragoons

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

north toward the Coeur d'Alene lands. On May 16, 1858, he was met by a force of about 600 Indians who, after blocking Steptoe's path forward, began to fight the next day. Steptoe withdrew after losses of men and upon running low in ammunition.

In 1867, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

established a reservation for the Coeur d'Alene tribe at the request of the territorial governor, but the tribe never accepted the reservation as Lake Coeur d'Alene and the main waterways, on which they depended for fishing, were not included. The tribe depended on the rivers and the lake for fish, camas, reeds for baskets, and other needs. In 1873, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

sent a commission to induce the Coeur d'Alenes to accept a reservation. Following negotiations, a reservation of approximately was established. The reservation boundaries included the Hangman Valley, the Coeur d'Alene River, the St. Joe River

The Saint Joe River (sometimes abbreviated St. Joe River) is a long tributary of Coeur d'Alene Lake in northern Idaho. Beginning at an elevation of in the Northern Bitterroot Range of eastern Shoshone County, it flows generally west through t ...

, and all but a small portion of Lake Coeur d'Alene

Lake Coeur d'Alene, officially Coeur d'Alene Lake ( ), is a natural dam-controlled lake in North Idaho, located in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. At its northern end is the city of Coeur d'Alene. It spans in length and rang ...

.

The agreement was implemented with an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

, which was intended to be temporary until Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

approved it. Cession of land was supposed to be compensated. Congress never approved the action, and in 1883 the United States conducted a survey of the reservation. Congress in 1886 authorized the Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

to negotiate with the tribe, to gain their cession of all of their land outside the reservation. In 1887 the tribe and the federal government came to an agreement under those terms, but Lake Coeur d'Alene and related waters were part of the reservation. In 1889, the tribe ceded the northern third of the reservation back to the federal government, including part of Lake Coeur d'Alene, for compensation. Unusually, in contrast to practices at the time, the reservation boundary was drawn across the lake, rather than by the meandering high water line. The agreement stated that it was not binding until ratified by Congress.

Prior to Senate ratification of both agreements, Idaho became a state. Congress passed the Idaho Statehood Act that ratified the state constitution, which contained a section disclaiming the state's rights to unappropriated public lands and lands owned by tribes. In 1891, Congress ratified the earlier agreements with the tribe. In 1894, the tribe ceded a one-mile wide strip (the "Harrison cession") for use by the Washington and Idaho Railway

The Washington and Idaho Railway was a shortline railroad that operated in the area south of Spokane, Washington, connecting the BNSF Railway at Marshall to Palouse, Washington, Harvard, Idaho, and Moscow, Idaho. It began operations in 2006 on ...

to extend its tracks. In 1908 Congress gave Idaho an area now known as Heyburn State Park.

This area of Idaho was known for mining and has long held the nickname of "Silver Valley." It has been the second-largest area of silver production in the country. From 1880-1980 the Coeur d'Alene basin was one of the most productive silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

, and zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

mining regions in the country. The waste from the mining, estimated at 72 million tons, contaminated land and downstream waters, including the Coeur d'Alene River and Lake Coeur d'Alene. As of 2012, the Silver Valley was the second largest Superfund

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the Environmental Protection Agency ...

cleanup site in the nation, as designated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it ...

(EPA).

Prior court action

For years the Coeur d'Alene tried to work with the state on clean-up and management of Lake Coeur d'Alene, but was unable to reach agreement on gaining a larger role. In 1991, the tribe notified the state of its intent to sue for title of the lake and submerged lands beneath. The case was brought in the U.S. District Court which initially held that a suit by the tribe against the state was barred by the Eleventh Amendment. The tribe appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit Court. The Ninth Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part, and the state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the Supreme Court,

In the Supreme Court, Justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

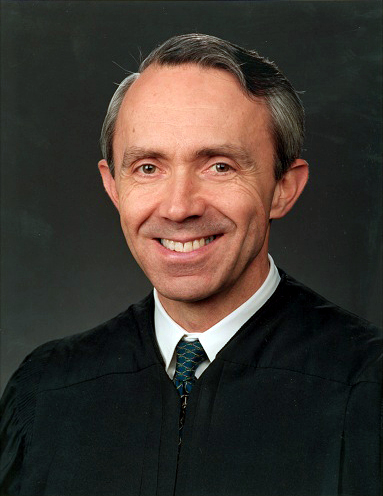

delivered the majority opinion which held that the Eleventh Amendment barred direct lawsuits by tribes against a state. The decision was 5-4, with Chief Justice William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

and Justices O'Connor, Scalia, and Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

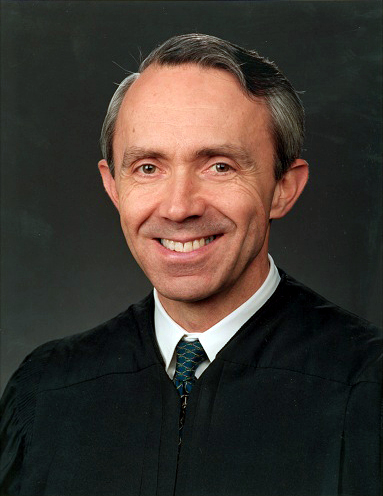

joining Kennedy. Justice David Souter

David Hackett Souter ( ; born September 17, 1939) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1990 until his retirement in 2009. Appointed by President George H. W. Bush to fill the seat ...

dissented, joined by Justices Stevens, Ginsburg, and Breyer.

The Coeur d'Alene tribe requested that the United States sue to quiet title to the submerged lands on the reservation. The tribe moved to intervene on the side of the United States in this suit, and the court granted the request. The court found that the earlier executive agreements had clearly intended to reserve the lake and submerged land for the use of the tribe, and ruled for the United States.

The state appealed the ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the decision of the trial court, pointing out additional information that supported the lower court's ruling that was not in the District Court's memorandum opinion.

The state again appealed and the Supreme Court granted ''certiorari

In law, ''certiorari'' is a court process to seek judicial review of a decision of a lower court or government agency. ''Certiorari'' comes from the name of an English prerogative writ, issued by a superior court to direct that the record of ...

''.

Supreme Court

Arguments

Steven W. Strack argued the cause for the state of Idaho. David C. Frederick argued the cause for the United States, and Raymond C. Givens argued the cause for the Coeur d'Alene tribe.Opinion of the court

Justice Souter delivered the opinion of the court. This decision was the opposite of the earlier decision in '' Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Idaho,'' with Justice O'Connor now voting with the dissenters in that case. Basically repeating his earlier dissent, Souter noted that the presumption was that the state had ownership of all submerged lands, unless it was clear that the United States had reserved those lands for itself. Souter observed that the 1873 executive order implicitly included the submerged lands and also noted that the 1888 report to Congress indicated that all of the submerged lands were retained in trust for the tribe, and that Congress knew this when they passed the Idaho statehood act. He also noted the trial court's finding that the federal government had consistently treated with the tribe over the submerged lands, including compensating the tribe for the railroad right of way. In this case it was clear that the United States had retained the rights of title to the submerged land, overcoming the presumption of state ownership. The decision of the Court of Appeals was affirmed, that the United States held title to the land.

Dissent

Chief Justice Rehnquist dissented from the majority opinion. He stated that once the Idaho statehood act was passed, the title to the submerged lands transferred to the state. Any subsequent look at actions of the Congress, even in ratifying agreements that antedated statehood were of no consequence, and should not have been considered by the majority. The only action that would have retained tribal and federal ownership of the submerged lands would have been an action prior to Idaho becoming a state. He would have reversed and remanded the case.Subsequent developments

A year after the decision, the tribe applied to theEnvironmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale ...

(EPA) for authority to enforce water standards under the Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the responsibiliti ...

. Negotiations with the state, the tribe and the EPA began but broke down when both the state and the EPA could not match the $5,000,000 budget provided by the tribe. In 2005, the EPA granted this authority, allowing the tribe to regulate non-members as necessary for the health and welfare of the tribe. The three parties came together again, and after arbitration, agreed on a management plan as part of a settlement in 2009.

The tribe has proceeded to file lawsuits requiring cleanup against mining companies for contamination of waters and land. State and federal politicians have moved to limit the damages that could be collected against the companies., 217 (1999).

References

Footnotes

Notes

External links

* {{Native American rights Aboriginal title case law in the United States 2001 in United States case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Native American case law Coeur d'Alene tribe United States Supreme Court cases of the Rehnquist Court 2001 in Idaho Legal history of Idaho Native American history of Idaho