Human rights movement in the Soviet Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the 1980s a human rights movement began to emerge in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

— freedom of expression, of

religious belief

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people often ...

, of national

self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

Gradually, under the pressure of official actions and responses these groups and interests coalesced in the

dissident milieu. The fight for civil and human rights focused on issues of

freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

,

freedom of conscience,

freedom to emigrate,

punitive psychiatry

Political abuse of psychiatry, also commonly referred to as punitive psychiatry, is the misuse of psychiatry, including diagnosis, detention, and treatment, for the purposes of obstructing the human rights of individuals and/or groups in a society ...

, and the plight of

political prisoners

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

. It was characterized by a new openness of dissent, a concern for legality, the rejection of any 'underground' and violent struggle.

Like other dissidents in the post-Stalin Soviet Union, human rights activists were subjected to a broad range of repressive measures. They received warnings from the police and the KGB; some lost their jobs, others were imprisoned or incarcerated in

psychiatric hospitals

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative ...

; dissidents were sent into exile within the country or pressured to emigrate.

Methods and activities

Samizdat documentation

The documentation of political repressions as well as citizens' reactions to them through ''

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

'' (unsanctioned self-publishing) methods played a key role in the formation of the human rights movement. Dissidents collected and distributed transcripts, open letters and appeals relating to specific cases of political repressions.

[''A Chronicle of Current Events (CCE)'' 5.1 (31 December 1968), "A Survey of samizdat in 1968".]

/ref>

The prototype for this type of writing was journalist Frida Vigdorova's record of the trial of poet Joseph Brodsky (convicted for " social parasitism" in early 1964). Similar documenting activity was taken up by dissidents in publications such as Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

's ''White Book'' (1967, on the Sinyavsky-Daniel case)[CCE 4.6 (31 October 1968) "An addition to the White Book about Sinyavsky and Daniel".]

/ref> and Pavel Litvinov

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov (russian: Па́вел Миха́йлович Литви́нов; born 6 July 1940) is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, human rights activist and former Soviet-era dissident.

Biography

The grandson of ...

's ''The Trial of the Four'' (1968, on the Galanskov–Ginzburg case).[CCE 1 (30 April 1968).]

/ref>

From 1968 on, the samizdat periodical ''A Chronicle of Current Events

''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (russian: Хро́ника теку́щих собы́тий, ''Khronika tekushchikh sobytiy'') was one of the longest-running ''samizdat'' periodicals of the post-Stalin USSR. This unofficial newsletter reported v ...

'' played a key role for the human rights movement. Founded in April 1968, the ''Chronicle'' ran until 1983, producing 65 issues in 14 years.[''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (in English).]

/ref> It documented the extensive human rights violations committed by the Soviet government and the ever-expanding samizdat publications (political tracts, fiction, translations) circulating among the critical and opposition-minded.

Protest letters and petitions

''Podpisanty'', literally signatories, were individuals who signed a series of petitions to officials and the Soviet press against political trials of the mid- to late-1960s.[CCE 1.2 (30 April 1968), "Protests about the trial".]

/ref> The ''podpisanty'' surge reached its high water mark during the trial of writers Aleksandr Ginzburg and Yuri Galanskov in January 1968.Larisa Bogoraz

Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz (russian: Лари́са Ио́сифовна Богора́з(-Брухман), full name: Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz-Brukhman, Bogoraz was her father's last name, Brukhman her mother's, August 8, 1929 – April 6, 20 ...

and Pavel Litvinov

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov (russian: Па́вел Миха́йлович Литви́нов; born 6 July 1940) is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, human rights activist and former Soviet-era dissident.

Biography

The grandson of ...

, who wrote an open letter protesting the trial of samizdat authors Alexander Ginsburg and Yuri Galanskov in January 1968. Appeals to the international community and human rights bodies later became a central method of early civic dissident groups such as the Action Group[CCE 8.10 (30 June 1969) "An appeal to the UN Commission on Human Rights".]

/ref> and the Committee on Human Rights, as well as the Helsinki Watch Groups.

Demonstrations

Limited in scope and number, several demonstrations nevertheless became significant landmarks of the human rights movement.

On 5 December 1965 (Soviet Constitution Day) a small rally in Moscow, which became known as the ( glasnost meeting), the first public and overtly political demonstration took place in the post-Stalin USSR. Responding to the criminal charges against the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Sinyavsky–Daniel trial

The Sinyavsky–Daniel trial (russian: Проце́сс Синя́вского и Даниэ́ля) was a show trial in the Soviet Union against the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel in February 1966. Sinyavsky and Daniel were convicted of ...

), a few dozen people gathered on Pushkin Square, calling for a trial open to the public and the media (glasny sud), as required by the 1961 RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure. The demonstration was one of the first organized actions by the civil right movement in the Soviet Union. Silent gatherings on that date became an annual event.

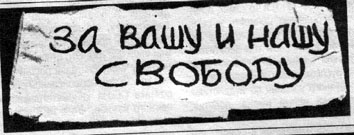

A similar demonstration followed in January 1967, when a group of young demonstrators protested against the recent arrests of samizdat authors, and against the introduction of new articles to the Criminal Code that restricted the right to protest.Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

, on 25 August 1968 seven dissidents demonstrated on Red Square (1968 Red Square demonstration

The 1968 Red Square demonstration (russian: Демонстра́ция 25 а́вгуста 1968 го́да) took place in Moscow on 25 August 1968. It was a protest by eight demonstrators against the invasion of Czechoslovakia on the night ...

).[CCE 3 (30 August 1968).]

/ref> The participants were subsequently sentenced to terms of imprisonment in labor camps, banishment to Siberia or incarceration in psychiatric prison-hospitals.[CCE 4.1 (30 October 1968), "The trial of the demonstrators on Red Square."]

On 30 October 1974, dissidents initiated a Day of the Political Prisoner in the USSR, intended to raise awareness of the existence and conditions of political prisoners throughout the Soviet Union.[CCE 33.1 (10 December 1974), "Political Prisoners' Day in the USSR."]

/ref> It was marked by hunger strikes in prisons and labor camps, and became an annual event marked by political prisoners in labor camps.

Civic watch groups

Starting with the Action (Initiative) Group formed in 1969 by 15 dissidents and the Committee on Human Rights in the USSR founded in 1970 by Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

, early Soviet human rights groups legitimized their work by referring to the principles enshrined in the Soviet constitution

During its existence, the Soviet Union had three different constitutions in force individually at different times between 31 January 1924 to 26 December 1991.

Chronology of Soviet constitutions

These three constitutions were:

* 1924 Constitut ...

and to international agreements.

These attempts were later succeeded by the more successful Moscow Helsinki Group

The Moscow Helsinki Group (also known as the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, russian: link=no, Московская Хельсинкская группа) is today one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 ...

(founded 1977). The group as well as the watch groups modeled after it brought the human rights dissidents to increased international attention.

The dissident civil and human rights groups were faced with harsh repressions, with most members facing imprisonment, punitive psychiatry, or exile.

Mutual aid for prisoners of conscience

Families of arrested dissidents often suffered repercussions such as the loss of jobs and opportunities to study. Relatives and friends of political prisoners supported each other through informal networks of volunteers. From 1974 on, this support was bolstered by the Solzhenitsyn Aid Fund

The Solzhenitsyn Aid Fund (officially Russian Public Fund to Aid Political Prisoners and their Families, also Fund for the Aid of Political Prisoners, Public Aid Fund) was a charity foundation and support network set up by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a ...

set up by the expelled dissident writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repres ...

. Despite limited resources and a crackdown by the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

, it was used to distribute funds and material support to the prisoners' families.

Background

In the wake of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

's 1956 "Secret Speech

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" (russian: «О культе личности и его последствиях», «''O kul'te lichnosti i yego posledstviyakh''»), popularly known as the "Secret Speech" (russian: секре ...

" condemning crimes of Stalinism and the following relative political relaxation ( Khrushchev Thaw), several events and factors formed the background for a dissident movement focused on civil and human rights.

Mayakovsky Square poetry readings

A major impulse for the current of dissent later known as the civil or human rights movement came from individuals concerned with literary and cultural freedom. During 1960-61 and again in 1965, public poetry readings in Moscow's Mayakovsky Square ( Mayakovsky Square poetry readings) served as a platform for politically charged literary dissent. Provoking measures ranging from expulsions from universities to lengthy labor camp terms for some of the participants, the regular meetings served as an incubator for many protagonists of the human rights movement, including writer Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

and student Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Константи́нович Буко́вский; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Russian-born British human rights activist and writer. From the late 195 ...

.

Dissidents in the mid-1960s

By the mid-1960s, dissenting voices in the Soviet Union also included movements of nations that had been deported under Stalin, religious movements that opposed the anti-religious state directives, and other groups such as reform communists and independent unions.

Some later human rights activists came from a circle of reform communists around Pyotr Grigorenko

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko ( uk, Петро́ Григо́рович Григоре́нко, russian: Пётр Григо́рьевич Григоре́нко, link=no, – 21 February 1987) was a high-ranking Soviet Army ...

, a Ukrainian army general who fell out of favor in the early 1960s. The Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

, an ethnic group who had been deported under Stalin and who had formed a movement petitioning to return to their homeland, would serve as an inspiration for the human rights activists, and their leader Mustafa Dzhemilev

Mustafa Abduldzhemil Jemilev ( crh, Mustafa Abdülcemil Cemilev, Мустафа Абдюльджемиль Джемилев, ), also known widely with his adopted descriptive surname Qırımoğlu "Son of Crimea" ( Crimean Tatar Cyrillic: , ; born ...

was later active in the broader human rights movement. Others who made an impact on the future movement were religious activists, such as Russian Orthodox priest Gleb Yakunin

Gleb Pavlovich Yakunin (russian: Глеб Па́влович Яку́нин; 4 March 1936 – 25 December 2014) was a Russian priest and dissident, who fought for the principle of freedom of conscience in the Soviet Union. He was a member of ...

, who penned an influential open letter to the Patriarch of Moscow

The Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' (russian: Патриарх Московский и всея Руси, translit=Patriarkh Moskovskij i vseja Rusi), also known as the Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, is the official title of the Bishop of Mo ...

Alexius I

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

in 1965, arguing that the Church must be liberated from the total control of the Soviet state.

The civil and human rights initiatives of the 1960s and 1970s managed to consolidate such different currents within the dissident spectrum by focusing on issues of freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, freedom to emigrate, and political prisoners. The movement became informed by "an idea of civic protest as an existentialist act, one not burdened with any political connotations."

History

Emergence of "defenders of rights"

The circle of human rights activists in the Soviet Union formed as a result of several events in 1966-68. Marking the end of Khrushchev's relative liberalism ( Khrushchev Thaw) and the beginning of the Brezhnev epoch (Brezhnev stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (russian: Пери́од засто́я, Períod zastóya, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Uni ...

), these years saw an increase in political repression. A succession of writers and dissidents warning against a return to Stalinism were put on trial, and the beginnings of political liberalization reforms in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

( Prague Spring) were crushed with military force.

Critically minded individuals reacted by petitioning against abuses and documenting them in ''samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

'' (underground press) publications, and a small group turned towards protesting openly and eventually began to appeal to the international community. Those who insisted on protesting rights violations became known as "defenders of rights" (''pravozashchitniki'').

Sinyavsky-Daniel trial (1966) – First rights-defense activity

In the mid-1960s, a number of writers who warned of a return to Stalinism were put on trial. One such a case was the 1966 trial of Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky, two writers who had published satirical writings under pseudonyms in the West. They were sentenced to seven years in a labor camp for " anti-Soviet agitation". The trial was perceived by many in the intelligentsia as a return to previous Soviet show trials. It provoked a number of demonstrations and petition campaigns, mostly in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

and Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, which emphasizes issues of creative freedom and the historical role of the writer in Russian society.In December 1965, the Sinyavsky-Daniel case motivated a small current of dissidents who decided to focus the legality of the trial. Mathematician Alexander Esenin-Volpin

Alexander Sergeyevich Esenin-Volpin (also written Ésénine-Volpine and Yessenin-Volpin in his French and English publications; russian: Алекса́ндр Серге́евич Есе́нин-Во́льпин, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪ ...

with the help of writer Yuri Galanskov

Yuri Timofeyevich Galanskov (russian: Ю́рий Тимофе́евич Галанско́в, 19 June 1939, Moscow - 4 November 1972, Mordovia) was a Russian poet, historian, human rights activist and dissident. For his political activities, suc ...

and student Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Константи́нович Буко́вский; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Russian-born British human rights activist and writer. From the late 195 ...

organized an unsanctioned rally on Pushkin Square (" glasnost meeting"). The demonstrators demanded an open trial for the writers as formally guaranteed by the Soviet Constitution. A "Civic Appeal" distributed through samizdat informed potential demonstrators of the rights being violated in the case and informed them of the possibility of formally legal protest.

Such focus on openly invoking rights was seen by many fellow dissidents to be utopian, and the demonstration as ineffective, carrying the risk of arrest, the loss of careers or imprisonment.Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

and Yuri Galanskov

Yuri Timofeyevich Galanskov (russian: Ю́рий Тимофе́евич Галанско́в, 19 June 1939, Moscow - 4 November 1972, Mordovia) was a Russian poet, historian, human rights activist and dissident. For his political activities, suc ...

, who had previously edited a number of underground poetry anthologies, compiled documents relating to the trial in a samizdat collection called ''The White Book'' (1966). Signaling that he considered this activity to be legal, Ginzburg sent a copy to the KGB, the Communist Party Central Committee as well as to publishers abroad.

Trial of the Four (1967) – Increased protests and samizdat

In 1967, Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

and Yuri Galanskov

Yuri Timofeyevich Galanskov (russian: Ю́рий Тимофе́евич Галанско́в, 19 June 1939, Moscow - 4 November 1972, Mordovia) was a Russian poet, historian, human rights activist and dissident. For his political activities, suc ...

were detained along with two other dissidents and charged with " anti-Soviet agitation" for their work on ''The White Book''. Ginzburg was sentenced to five years, Galanskov to seven years in labor camps. Their trial became another landmark in the rights-defense movement and motivated renewed protest (Trial of the Four

The Trial of the Four, also Galanskov–Ginzburg trial, was the 1968 trial of Yuri Galanskov, Alexander Ginzburg, Alexey Dobrovolsky and Vera Lahkova for their involvement in samizdat publications. The trial took place in Moscow City Court on Janu ...

).

In January 1967, a protest was organized against the arrest of Ginzburg and Galanskov, and against the introduction new laws classifying public gatherings or demonstrations as a crime. Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Константи́нович Буко́вский; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Russian-born British human rights activist and writer. From the late 195 ...

, Vadim Delaunay, Victor Khaustov and Evgeny Kushev were arrested for organizing and taking part. At his own closed trial in September 1967, Bukovsky used his final words to attack the regime's failure to respect the law or follow legal procedures in its conduct of the case.Pavel Litvinov

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov (russian: Па́вел Миха́йлович Литви́нов; born 6 July 1940) is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, human rights activist and former Soviet-era dissident.

Biography

The grandson of ...

.Larisa Bogoraz

Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz (russian: Лари́са Ио́сифовна Богора́з(-Брухман), full name: Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz-Brukhman, Bogoraz was her father's last name, Brukhman her mother's, August 8, 1929 – April 6, 20 ...

(wife of imprisoned writer Yuli Daniel

Yuli Markovich Daniel ( rus, Ю́лий Ма́ркович Даниэ́ль, p=ˈjʉlʲɪj ˈmarkəvʲɪtɕ dənʲɪˈelʲ, a=Yuliy Markovich Daniel'.ru.vorb.oga; 15 November 1925 — 30 December 1988) was a Russian writer and Soviet dissident ...

) and physics teacher Pavel Litvinov

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov (russian: Па́вел Миха́йлович Литви́нов; born 6 July 1940) is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, human rights activist and former Soviet-era dissident.

Biography

The grandson of ...

wrote an open letter protesting the trial of Ginzburg and Galanskov. The appeal departed from the accepted tradition of addressing appeals to Soviet officials and became the first direct appeal by dissidents to the international public. Reminding readers of the terror of Stalinism, Bogoraz and Litvinov listed in great detail the violations of law and justice committed during the trial, and asked the Soviet and world public to demand that the prisoners be released from custody and that the trial be repeated in the presence of international observers. The document was signed with their full names and addresses.

1968 Red Square demonstration (1968)

In August 1968, the Prague Spring became the second major development from which the human rights movement emerged. For many members of the intelligentsia,

In August 1968, the Prague Spring became the second major development from which the human rights movement emerged. For many members of the intelligentsia, Alexander Dubček

Alexander Dubček (; 27 November 1921 – 7 November 1992) was a Slovak politician who served as the First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) (''de facto'' leader of Czechoslovak ...

's political liberalization reforms were connected with the hope for a decline in repressions and a "socialism with a human face". In August 1968, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and its main allies in the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

invaded the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

in order to halt the reforms.Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːətʲ) is one of the oldest and largest squares in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Owing to its historical significance and the adjacent historical build ...

against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

(1968 Red Square demonstration

The 1968 Red Square demonstration (russian: Демонстра́ция 25 а́вгуста 1968 го́да) took place in Moscow on 25 August 1968. It was a protest by eight demonstrators against the invasion of Czechoslovakia on the night ...

). All participants were arrested. None of the participants plead guilty, and they were subsequently sentenced to labor camps or of psychiatric imprisonment. Poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya

Natalya Yevgenyevna Gorbanevskaya ( rus, Ната́лья Евге́ньевна Горбане́вская, p=nɐˈtalʲjə jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvnə ɡərbɐˈnʲefskəjə, a=Natal'ya Yevgen'yevna Gorbanyevskaya.ru.vorb.oga; 26 May 1936 – 29 Nove ...

collected testimonies on the demonstration as ''Noon'' (1968) before her incarceration in 1970.

First organized human rights activism

''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (1968–1982)

As a result of contacts between family members of political prisoners and the increased samizdat activity in the wake of trials, critically minded adults and youngsters in Moscow (later they would be known as

As a result of contacts between family members of political prisoners and the increased samizdat activity in the wake of trials, critically minded adults and youngsters in Moscow (later they would be known as dissidents

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

) were confronted by a growing range of information about ongoing political repression in the Soviet Union

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, tens of millions of people suffered political repression, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution. It culminated during the Stalin era, then declined, but it continued to exist ...

.

In April 1968, marking the declared International Human Rights Year by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, anonymous editors in Moscow released the first issue of the ''Chronicle of Current Events''. The typewritten samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

bulletin adopted a documentary style and reported the activities of dissenters, the appearance of new samizdat (underground) publications, the repressive measures of the Soviet State, and conditions within the penitentiary system."Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers."

Over the 15 years of its existence, the ''Chronicle'' expanded its coverage to include every form of repression against the constituent nations, confessional and ethnic groups of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. It served as the backbone of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union.Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

and Yury Galanskov and public reactions to those closed judicial hearings in Moscow, the last published (circulated) and translated issue, No 64, was over one hundred pages long and its contents listed trials, arrests and the protests and conditions in and outside labour camps, prisons and psychiatric hospitals all over the Soviet Union.

The Action Group; the Committee; the Soviet section of ''Amnesty International'' (1969–1979)

While the early human rights movement was dominated by individual activists, the end of the 1960s saw the appearance of the first civil and human rights organizations in the Soviet Union.

The formation of these groups broke a taboo on organized public activity by non-state structures.

The Soviet press routinely attacked dissidents for tenuous links to émigré organisations like the Frankfurt-based NTS or National Alliance of Russian Solidarists

The National Alliance of Russian Solidarists (NTS; russian: Народно-трудовой союз российских солидаристов; НТС; ''Narodno-trudovoy soyuz rossiyskikh solidaristov'', ''NTS'') is a Russian anticommunist o ...

. It seemed self-evident that the State would respond to the creation of an organization within the USSR by immediately arresting all of its members. The new organizations legitimized their work by referring to principles enshrined in the current Soviet Constitution

During its existence, the Soviet Union had three different constitutions in force individually at different times between 31 January 1924 to 26 December 1991.

Chronology of Soviet constitutions

These three constitutions were:

* 1924 Constitut ...

(1936) and, for the first time, by appealing to international agreements (to some of which the USSR would in time become a signatory). Each new organisation took particular care to emphasize the legality of its actions.

* The Initiative (or Action) Group for Human Rights in the USSR was founded in May 1969 by Soviet dissidents to unify existing human rights circles and began its activities with a petition to the UN Commission on Human Rights

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was a functional commission within the overall framework of the United Nations from 1946 until it was replaced by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006. It was a subsidiary body of ...

and other international bodies on behalf of the victims of Soviet repression. It included key figures from the rights defense bulletin ''Chronicle of Current Events

''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (russian: Хро́ника теку́щих собы́тий, ''Khronika tekushchikh sobytiy'') was one of the longest-running ''samizdat'' periodicals of the post-Stalin USSR. This unofficial newsletter reported v ...

'' two members from Ukraine (Altunyan and Plyushch) and the young Crimean Tatar activist Mustafa Dzhemilev

Mustafa Abduldzhemil Jemilev ( crh, Mustafa Abdülcemil Cemilev, Мустафа Абдюльджемиль Джемилев, ), also known widely with his adopted descriptive surname Qırımoğlu "Son of Crimea" ( Crimean Tatar Cyrillic: , ; born ...

in Tashkent. By May 1970, six of the fifteen original members were arrested or exiled and in the years that followed more would be forced into emigration. The group never officially disbanded, but its last free member Tatyana Velikanova

Tatyana Mikhailovna Velikanova (russian: link=no, Татья́на Миха́йловна Велика́нова, 3 February 1932 in Moscow – 19 September 2002 in Moscow) was a mathematician and Soviet dissident. A veteran of the human rights ...

was arrested in 1979 and imprisoned the following year.

* The Committee on Human Rights in the USSR was founded in November 1970 by Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

together with physicists Andrei Tverdokhlebov

Andrei Nikolayevich Tverdokhlebov (russian: Андре́й Никола́евич Твердохле́бов, 30 September 1940, Moscow – 3 December 2011, Pennsylvania, United States) was a Soviet physicist, dissident and human rights activist ...

and Valery Chalidze. It aimed to apply a more scholarly approach, exploring the application of human rights in a socialist context and was centered upon Chalidze's samizdat journal ''Social Problems''.Andrei Tverdokhlebov

Andrei Nikolayevich Tverdokhlebov (russian: Андре́й Никола́евич Твердохле́бов, 30 September 1940, Moscow – 3 December 2011, Pennsylvania, United States) was a Soviet physicist, dissident and human rights activist ...

, Valentin Turchin

Valentin Fyodorovich Turchin (russian: Валенти́н Фёдорович Турчи́н, 14 February 1931 in Podolsk – 7 April 2010 in Oakland, New Jersey) was a Soviet and American physicist, cybernetician, and computer scientist. He d ...

, Yuri Orlov

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov (russian: Ю́рий Фёдорович Орло́в, 13 August 1924 – 27 September 2020) was a particle accelerator physicist, human rights activist, Soviet dissident, founder of the Moscow Helsinki Group, a founding ...

, Sergei Kovalev

Sergei Adamovich Kovalyov (also spelled Sergey Kovalev; russian: link=no, Сергей Адамович Ковалёв; 2 March 1930 – 9 August 2021) was a Russian human rights activist and politician. During the Soviet period he was a diss ...

, in the same month as the USSR ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, fr ...

. It was registered in September 1974 by the Amnesty International Secretariat in London.

Crisis and international recognition (1972–1975)

In 1972, the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

initiated "Case 24", a wide-ranging crackdown intended to suppress the ''Chronicle of Current Events''. Accused of " anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda", two of the arrested editors, Petr Yakir and Victor Krasin, began to collaborate with their interrogators. Over two hundred dissidents were called for interrogation and the two men appeared on national TV, expressing regret for their past activities. There would be further arrests, threatened the KGB, for every issue of the ''Chronicle'' published after the TV broadcast.The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr So ...

'', the Soviet leadership decided to arrest Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, strip him of his Soviet citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

and deport him in February 1974 to West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

.The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr So ...

, Solzhenitsyn set up a fund in Switzerland (Solzhenitsyn Aid Fund

The Solzhenitsyn Aid Fund (officially Russian Public Fund to Aid Political Prisoners and their Families, also Fund for the Aid of Political Prisoners, Public Aid Fund) was a charity foundation and support network set up by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a ...

) and with the help of Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

money was distributed across the Soviet Union to political and religious prisoners and their families.[ "'Do what will not get done without you': Natalya Solzhenitsyn describes the history and present-day activities of the Solzhenitsyn Fund", Kifa.ru online newspaper, 28 April 2004 (date of access 23 March 2019).]

In September 1974, the Soviet section of Amnesty International was registered by the Amnesty International Secretariat in London.

In December 1975 Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

was awarded the Nobel Peace prize "for his struggle for human rights, for disarmament, and for cooperation between all nations". He was not allowed to leave the Soviet Union to collect it. His speech was read by his wife Yelena Bonner

Yelena Georgiyevna Bonner (russian: link=no, Елена Георгиевна Боннэр; 15 February 1923 – 18 June 2011)[ ...](_blank)

at the ceremony in Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

.[Acceptance Speech](_blank)

Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, Norway, December 10, 1975. On the day the prize was awarded, Sakharov was in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, demanding admission to the trial of human rights activist Sergei Kovalev

Sergei Adamovich Kovalyov (also spelled Sergey Kovalev; russian: link=no, Сергей Адамович Ковалёв; 2 March 1930 – 9 August 2021) was a Russian human rights activist and politician. During the Soviet period he was a diss ...

. In his Nobel lecture, titled "Peace, Progress, Human Rights", Sakharov included a list of prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in the USSR, stating that he shared the prize with them.[Peace, Progress, Human Rights](_blank)

Sakharov's Nobel Lecture, Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, Norway, December 11, 1975.

Helsinki period (1975–1981)

In August 1975, during the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was a key element of the détente process during the Cold War. Although it did not have the force of a treaty, it recognized the boundaries of postwar Europe and established a mechanism f ...

(CSCE) in Helsinki, Finland, the eight member countries of the Warsaw Pact became co-signatories of the Helsinki Final Act (Helsinki Accords). Despite efforts to exclude the clauses, the Soviet government ultimately accepted a text containing unprecedented commitments to human rights as part of diplomatic relations between the signatories.BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...

and

Radio Liberty

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

. Presented as a diplomatic triumph of the Soviet Union, the text of the document was also reprinted in ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

.''

Of particular interest for dissidents across the Soviet bloc was the "Third Basket" of the Final Act. According to it, the signatories had to "respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief." The signatories also confirmed "the right of the individual to know and act upon his rights and duties in this field."

Founding of Helsinki watch groups

In the years 1976-77 members of the dissident movement formed several "Helsinki Watch Groups" in different cities to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the Helsinki Final Act:

* The

Moscow Helsinki Group

The Moscow Helsinki Group (also known as the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, russian: link=no, Московская Хельсинкская группа) is today one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 ...

was founded in May 1976 by physicist

Yuri Orlov

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov (russian: Ю́рий Фёдорович Орло́в, 13 August 1924 – 27 September 2020) was a particle accelerator physicist, human rights activist, Soviet dissident, founder of the Moscow Helsinki Group, a founding ...

. Despite severe repressions, it played a great role in East-West relations, revealing Soviet non-compliance with the Helsinki Final Act such as the continued

political abuse of psychiatry

Political abuse of psychiatry, also commonly referred to as punitive psychiatry, is the misuse of psychiatry, including diagnosis, detention, and treatment, for the purposes of obstructing the human rights of individuals and/or groups in a society ...

.

* A special

Working Commission on the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes was founded in January 1977 under the aegis of the Moscow Helsinki Group. It was advised by psychiatrists and jurists, and continued its work until its last member was arrested in 1981.

Following the example, other groups were formed:

* The

Ukrainian Helsinki Group

The Ukrainian Helsinki Group ( uk, Українська Гельсінська Група) was founded on November 9, 1976, as the "Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords on Human Rights" ( uk, Українс ...

was founded in November 1976 to monitor

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

in the

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

. The group was active until 1981, when all members were jailed.

* The

Lithuanian Helsinki Group was founded in November 1976 to monitor human rights in the

Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

. It ceased to exist in 1982 as a result of arrests, deaths, and emigration.

* The Georgian Helsinki Group was founded in January 1977 to monitor human rights in the

Georgian SSR

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

. It was active until the arrest and trial of several members of the group in 1977-1978. It was restarted in the spring of 1985 and eventually became the political party Georgian Helsinki Union, headed by

Zviad Gamsakhurdia

Zviad Konstantines dze Gamsakhurdia ( ka, ზვიად გამსახურდია, tr; russian: Звиа́д Константи́нович Гамсаху́рдия, Zviad Konstantinovich Gamsakhurdiya; 31 March 1939 – 31 December 1 ...

.

* The Armenian Helsinki Group was founded in April 1977. In addition to monitoring the observance of the

Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, also known as Helsinki Accords or Helsinki Declaration was the document signed at the closing meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland, between ...

in the

Armenian SSR, it intended to seek the Republic's acceptance as a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

and the unification with Armenia of

Nagorny Karabakh and

Nakhichevanik. In December 1977 two members of the Group were arrested and its activity ceased.

Similar initiatives began in Soviet

satellite states

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

, such as the informal civic initiative

Charter 77

Charter 77 (''Charta 77'' in Czech and Slovak) was an informal civic initiative in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic from 1976 to 1992, named after the document Charter 77 from January 1977. Founding members and architects were Jiří Něm ...

in the

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

and the

Workers' Defence Committee

The Workers' Defense Committee ( pl, Komitet Obrony Robotników , KOR) was a Polish civil society group that was established to give aid to prisoners and their families after the June 1976 protests and ensuing government crackdown. KOR was an exam ...

, later Committee for Social Defense, in Poland.

Impact and persecution of Helsinki watch groups

Materials provided by the Helsinki groups were used at the follow-up

Belgrade conference on verification of the Helsinki accords on 4 October 1977. The conference became the first international meeting on a governmental level in which the Soviet Union was accused of human rights violations.

In January 1979, the

Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), also known as the U.S. Helsinki Commission, is an independent U.S. government agency created by Congress in 1975 to monitor and encourage compliance with the Helsinki Final Act and o ...

nominated the Helsinki Groups of the Soviet Union for the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

.

In 1977-1979 and again in 1980-1982, the KGB reacted to the Helsinki Watch Groups by launching large-scale arrests and sentencing its members to in prison, labor camp, internal exile and psychiatric imprisonment.

During the 1970s the Moscow and the Ukrainian Helsinki Groups managed to recruit new members after an initial wave of arrests. The Ukrainian group also had representatives abroad, with

Leonid Plyushch

Leonid Ivanovych Plyushch ( uk, Леоні́д Іва́нович Плющ, ; 26 April 1938, Naryn, Kirghiz SSR – 4 June 2015, Bessèges, France) was a Ukrainian mathematician and Soviet dissident.

Although he was employed to work on Soviet ...

in France and

Nadiya Svitlychna,

Pyotr Grigorenko

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko ( uk, Петро́ Григо́рович Григоре́нко, russian: Пётр Григо́рьевич Григоре́нко, link=no, – 21 February 1987) was a high-ranking Soviet Army ...

and Nina Strokata in the United States.

In the early 1980s, with the Soviet Union's international reputation damaged by the

invasion of Afghanistan, persecution of dissidents and human rights activists intensified. This spelled the end of the groups that were still active at the time. By the early 1980s, the Moscow Helsinki Group was scattered in prisons, camps and exile.

When the 74-year-old attorney

Sofya Kalistratova was threatened with arrest in Moscow in 1982, the last remaining members of the Moscow group who had not been arrested announced the dissolution of the group. In Lithuania, four members of the Helsinki group were incarcerated, and an additional member, the priest

Bronius Laurinavičius, was killed. The Ukrainian Helsinki Group, although faced with some of the heaviest losses, never formally disbanded. In the early 1980s, when 18 members of the Ukrainian group were incarcerated in the forced labor camp near Kuchino in the Urals alone, the Ukrainian group stated that its activities had been "displaced" to the camps.

Late Soviet Union (1980-1992)

In 1980,

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

was forcibly exiled from Moscow to the closed city of

Gorky to live under

KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

surveillance and to disrupt his contact with activists and foreign journalists. His wife

Yelena Bonner

Yelena Georgiyevna Bonner (russian: link=no, Елена Георгиевна Боннэр; 15 February 1923 – 18 June 2011)[ ...](_blank)

was permitted to travel between Moscow and Gorky. With her help, Sakharov was able to send appeals and essays to the West until 1984 when she was also arrested and confined by court order to Gorky.

The death

Anatoly Marchenko

Anatoly Tikhonovich Marchenko (russian: Анато́лий Ти́хонович Ма́рченко, 23 January 1938 – 8 December 1986) was a Soviet dissident, author, and human rights campaigner, who became one of the first two recipients (al ...

, a founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Group, in prison after months on hunger strike in 1986 caused an international outcry. It marked a turning point in the initial insistence of Mikhail Gorbachev that there were no political prisoners in the USSR.

In 1986,

Mikhail Gorbachev, who had initiated the policies of

perestroika and

glasnost, called Sakharov to tell him that he and his wife could return to Moscow.

In the late 1980s, with

glasnost and

perestroika underway, some of the Helsinki watch groups resumed their work. With the return of the first Ukrainian group members from the camps, they resumed their work for a democratic Ukraine in 1987. Their group later became the nucleus for a number of political parties and democratic initiatives. The Moscow Helsinki Group resumed its activities in 1989 and continues to operate today.

Legal context

Civil and human rights frameworks

The emerging civil rights movement of the mid-1960s turned its attention to the guarantees enshrined in the Soviet constitution:

*

1936 Soviet Constitution

Events

January–February

* January 20 – George V of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India, dies at his Sandringham Estate. The Prince of Wales succeeds to the throne of the United Kingdom as King E ...

, in force until 1977

*

1977 Soviet Constitution, in force until the dissolution of the Soviet Union

*1961 RSFSR Code of Criminal Procedure

The human rights movement from the 1970s turned its attention to international agreements:

* 1948

U.N.

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, ...

* 1975

Helsinki Final Act, and its "Third Basket" containing human rights clauses, signed by the USSR

Existing human rights guarantees were neither well known to people living under Communist rule nor taken seriously by the Communist authorities. In addition, Western governments did not emphasize human rights ideas in the early

détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

period.

Persecution

While the authors of the samizdat bulletin ''

Chronicle of Current Events

''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (russian: Хро́ника теку́щих собы́тий, ''Khronika tekushchikh sobytiy'') was one of the longest-running ''samizdat'' periodicals of the post-Stalin USSR. This unofficial newsletter reported v ...

'' and the members of the various human rights groups maintained that their activity was not illegal, several articles of the RSFSR Criminal Code were routinely used against activists in the movement:

* Article 70 –

anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda – punished the creation and circulation of "slanderous fabrications that target the Soviet political and social system". Its penalty was up to 7 years of imprisonment followed by up to 5 years of internal exile.

* Article 72 introduced the capital offense of "organizational activity directed to the commission of especially dangerous crimes against the state and also participation in an anti-Soviet organization"

* Article 227 punished creation or participation in a religious group that "induces citizens to refuse social activity or performance of civic duties".

Two articles were added to the Criminal Code in September 1966 in the wake of the

Sinyasky-Daniel trial:

* Article 190-1 punished "systematic dissemination of deliberately false statements derogatory to the Soviet state and social system"

* Article 190-3 punished "group activities involving a grave breach of public order, or disobedience to the legitimate demands of representatives of authority"

Another article was introduced in October 1983:

* Article 188-3 allowed the state to extend the terms of convicts, facilitating the ongoing persecution of political prisoners

Prior to 1960 and the introduction of the new RSFSR Criminal Article 58 described the capital offense of knowingly or unknowingly participating in an organization deemed "counter-revolutionary". It was not retained after 1960, but it was used to prosecute and imprison several older rights activists (for instance,

Vladimir Gershuni) in the Stalin and Khrushchev years.

See also

*

Soviet dissidents

*

Human rights in the Soviet Union

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

*

:Soviet human rights activists

*

Charter 77

Charter 77 (''Charta 77'' in Czech and Slovak) was an informal civic initiative in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic from 1976 to 1992, named after the document Charter 77 from January 1977. Founding members and architects were Jiří Něm ...

*

Human rights in Russia

Human rights in Russia have routinely been criticized by international organizations and independent domestic media outlets. Some of the most commonly cited violations include deaths in custody, the widespread and systematic use of torture by s ...

Notes

References

Primary

Secondary

Further reading

General

*

*

*

*

Helsinki period

*

*

*

Further studies and articles

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

* {{Cite web, url=https://samizdatcollections.library.utoronto.ca/content/timeline-rights-activism-soviet-union, title=Timeline of Rights Activism in the Soviet Union, website=Project for the Study of Dissidence and Samizdat, publisher=University of Toronto

*

Soviet democracy movements

Soviet opposition groups

Persecution of dissidents in the Soviet Union

Underground culture

Political opposition

Era of Stagnation

Political and cultural purges

1960s in the Soviet Union

1970s in the Soviet Union

1980s in the Soviet Union

In August 1968, the Prague Spring became the second major development from which the human rights movement emerged. For many members of the intelligentsia,

In August 1968, the Prague Spring became the second major development from which the human rights movement emerged. For many members of the intelligentsia,  As a result of contacts between family members of political prisoners and the increased samizdat activity in the wake of trials, critically minded adults and youngsters in Moscow (later they would be known as

As a result of contacts between family members of political prisoners and the increased samizdat activity in the wake of trials, critically minded adults and youngsters in Moscow (later they would be known as