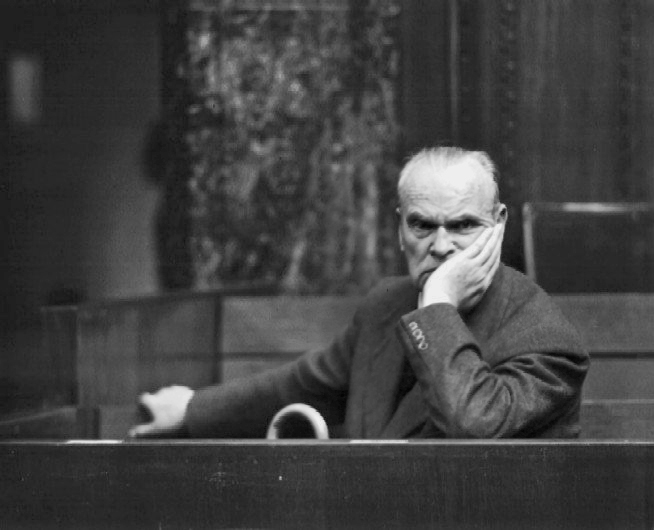

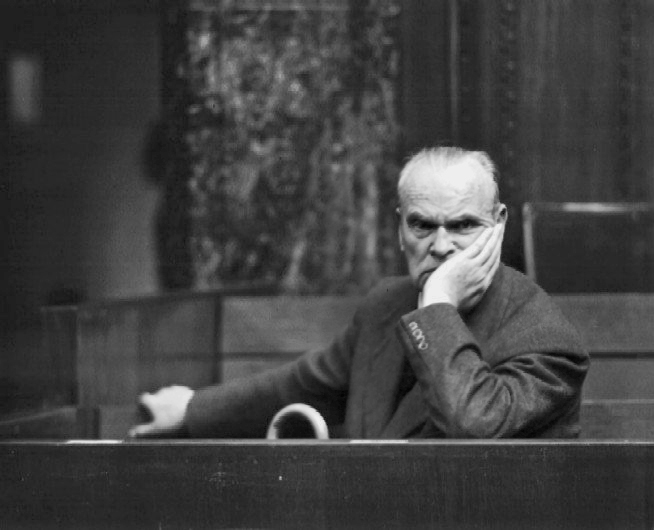

Hugo Sperrle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wilhelm Hugo Sperrle (7 February 1885 – 2 April 1953), also known as Hugo Sperrle, was a

Sperrle was assisted by the

Sperrle was assisted by the

The Nationalists turned to destroying the Republican army enclave along the

The Nationalists turned to destroying the Republican army enclave along the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

military aviator in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and a Generalfeldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

in the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Sperrle joined the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

in 1903. He served in the artillery upon the outbreak of World War I. In 1914 he joined the Luftstreitkräfte

The ''Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte'' (, German Air Force)—known before October 1916 as (Flyer Troops)—was the air arm of the Imperial German Army. In English-language sources it is usually referred to as the Imperial German Air Service, alth ...

as an observer then trained as a pilot. Sperrle ended the war at the rank of Hauptmann

is a German word usually translated as captain when it is used as an officer's rank in the German, Austrian, and Swiss armies. While in contemporary German means 'main', it also has and originally had the meaning of 'head', i.e. ' literally ...

(Captain) in command of an aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of im ...

attachment of a field army.

In the inter-war period Sperrle was appointed to the General Staff in the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

, serving the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

in the aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or strategic targets; fighter aircraft battling for contr ...

branch. In 1934 after Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

seized power, Sperrle was promoted to Generalmajor

is the Germanic variant of major general, used in a number of Central and Northern European countries.

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

is the second lowest general officer rank in the Royal Danish Army and Royal Danish Air Force. As a two-s ...

(Brigadier

General) and transferred from the army to the Luftwaffe. Sperrle was given command of the Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

in November 1936 and fought with the expeditionary force in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

until October 1937.

Sperrle was appointed as commanding officer of ''Luftwaffengruppenkommando'' 3 (Air Force Group Command 3) the forerunner of ''Luftflotte'' 3 (Air Fleet 3) in February 1938. Sperrle was used during the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

and Czech crisis by the Nazi leadership to threaten other governments with bombardment. Sperrle attended several important meetings with Austrian and Czech leaders for this purpose upon the invitation of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

.

In September 1939 World War II began with the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

. Sperrle and his air fleet served exclusively on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

. He played a crucial role in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

and Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

in 1940. In 1941 Sperrle directed operations during The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

over Britain. From mid-1941 his air fleet became the sole command in the west. Through 1941 and 1942 he defended German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

against the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

, as well as the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

from 1943. Sperrle's command was depleted in the battles of attrition forced on him by the Combined Bomber Offensive

The Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) was an Allied offensive of strategic bombing during World War II in Europe. The primary portion of the CBO was directed against Luftwaffe targets which was the highest priority from June 1943 to 1 April 1944. ...

.

By mid-1944, Sperrle's air fleet had been reduced to impotence and it could not repel the Allied landings in Western Europe. As a consequence, Sperrle was dismissed to the Führerreserve

The (“Leaders Reserve” or "Reserve for Leaders") was set up in the German Armed Forces during World War II in 1939 as a pool of temporarily unoccupied high-ranking military officers awaiting new assignments. The various military branches an ...

and never held a senior command again. On 1 May 1945 he was captured by the British. After the war, he was charged with war crimes at the High Command Trial but was acquitted. Sperrle was involved in the bribery of senior Wehrmacht officers

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

.

Early life and World War I

Sperrle was born in the town of Ludwigsburg, in theKingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which existe ...

, German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

on 7 February 1885 the son of a brewery proprietor, Johannes Sperrle and his wife Luise Karoline, née Nägele. He joined the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

on 5 July 1903 as a ''Fahnenjunker

''Fahnenjunker'' (short Fhj or FJ, en, officer cadet; ) is a military rank of the Bundeswehr and of some former German armed forces. In earlier German armed forces it was also the collective name for many officer aspirant ranks. It was establi ...

'' (officer cadet). Sperrle was assigned to the 8th Württemberg Infantry Regiment ("Großherzog Friedrich von Baden" Nr. 126), a regiment in the Army of Württemberg

The army of the German state of Württemberg was until 1918 known in Germany as the ''Württembergische Armee''.

Its troops were maintained by Württemberg for its national defence and as a unit of the Swabian Circle (district) of Holy Roman Emp ...

, and after a year received his commission and promotion to Leutnant

() is the lowest Junior officer rank in the armed forces the German-speaking of Germany (Bundeswehr), Austrian Armed Forces, and military of Switzerland.

History

The German noun (with the meaning "" (in English "deputy") from Middle High Ge ...

on 28 October 1912. Sperrle served another year until his promotion to ''Oberleutnant

() is the highest lieutenant officer rank in the German-speaking armed forces of Germany (Bundeswehr), the Austrian Armed Forces, and the Swiss Armed Forces.

Austria

Germany

In the German Army, it dates from the early 19th century. Tr ...

'' (second lieutenant) in October 1913.

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Sperrle was training as an artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

spotter in the ''Luftstreitkräfte

The ''Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte'' (, German Air Force)—known before October 1916 as (Flyer Troops)—was the air arm of the Imperial German Army. In English-language sources it is usually referred to as the Imperial German Air Service, alth ...

'' (German Army Air Service). On 28 November 1914 Sperrle was promoted to Hauptmann

is a German word usually translated as captain when it is used as an officer's rank in the German, Austrian, and Swiss armies. While in contemporary German means 'main', it also has and originally had the meaning of 'head', i.e. ' literally ...

. Sperrle did not distinguish himself in battle as his fellow staff officers in World War II had done, but he forged a solid record in the aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of im ...

field.

Sperrle served first as an observer, then trained as a pilot with the 4th Field Flying Detachment (''Feldfliegerabteilung'') at the '' Kriegsakademie'' (War Academy). Sperrle went on to command the 42nd and 60th Field Flying Detachments, then led the 13th Field Flying Group. After suffering severe injuries in a crash,

Sperrle moved to the air observer school at Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

thereafter and when the war ended he was in command of flying units attached to the 7th Army. For his command he was awarded the House Order of Hohenzollern

The House Order of Hohenzollern (german: Hausorden von Hohenzollern or ') was a dynastic order of knighthood of the House of Hohenzollern awarded to military commissioned officers and civilians of comparable status. Associated with the various ...

with Swords.

Inter-war years

Sperrle joined the ''Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

'' and commanded an aviation detachment. He then joined the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

''. Sperrle commanded units in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

including the ''Freiwilligen Fliegerabteilungen'' 412 under the leadership of Erhard Milch

Erhard Milch (30 March 1892 – 25 January 1972) was a German general field marshal ('' Generalfeldmarschall'') of Jewish heritage who oversaw the development of the German air force (''Luftwaffe'') as part of the re-armament of Nazi Germany fo ...

. Sperrle fought on the East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

border during the 1919 conflict with Poland. He assumed command on 9 January 1919.

On 1 December 1919, commander-in-chief of the German army, Hans von Seeckt issued a directive for the creation of 57 committees, encompassing all the military branches, to compile detailed studies of German war experiences. Helmuth Wilberg

Helmuth Wilberg (1 June 1880 – 20 November 1941) was a German officer of Jewish ancestry and a ''Luftwaffe'' General of the Air Force during the Second World War.

Military career

Wilberg joined the 80. Fusilier Regiment "von Gersdorff" (''Ku ...

led the air service sector and Sperrle was one of 83 commanders ordered to assist. The air staff studies were conducted through 1920.

General Staff

Sperrle served on the air staff for ''Wehrkreis'' V (Military District 5) inStuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the Sw ...

from 1919 to 1923, then the Defence Ministry until 1924. Sperrle then served on the staff of the 4th Infantry Division near Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

. Sperrle travelled to Lipetsk

Lipetsk ( rus, links=no, Липецк, p=ˈlʲipʲɪtsk), also romanized as Lipeck, is a city and the administrative center of Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the banks of the Voronezh River in the Don basin, southeast of Moscow. Popu ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

at this time, where the Germans maintained a secret air base and founded the Lipetsk fighter-pilot school. Sperrle purportedly visited the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

to observe Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

exercises. At Lipetsk, Hugo Sperrle and Kurt Student

Kurt Arthur Benno Student (12 May 1890 – 1 July 1978) was a German general in the Luftwaffe during World War II. An early pioneer of airborne forces, Student was in overall command of developing a paratrooper force to be known as the '' Fallsch ...

acted as senior directors which trained some 240 German pilots between 1924 and 1932.

The air staff remained small, but Sperrle's contingent were present in the 4,000 officers retained in the military. In 1927 Sperrle, at the rank of ''Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

'', replaced Wilberg as head of the air staff at the Waffenamt

''Waffenamt'' (WaA) was the German Army Weapons Agency. It was the centre for research and development of the Weimar Republic and later the Third Reich for weapons, ammunition and army equipment to the German Reichswehr and then Wehrmacht

...

an Truppenamt (Weapons and Troop Office). Sperrle was selected for his expertise in technical matters; he was seen as highly qualified staff officer with combat experience in commanding the flying units of the 7th army during the war. On 1 February 1929 Sperrle was replaced with Hellmuth Felmy

Hellmuth Felmy (28 May 1885 – 14 December 1965) was a German general and war criminal during World War II, commanding forces in occupied Greece and Yugoslavia. A high-ranking Luftwaffe officer, Felmy was tried and convicted in the 1948 Hostag ...

. Sperrle's departure came as he was pressing for an autonomous aviation authority. Felmy persisted, and on 1 October 1929, the Inspektion der Waffenschulen und der Luftwaffe came into existence under the command of Major General Hilmar von Mittelberger—it was the first use of the term "Luftwaffe". By 1 November 1930, the embryonic air headquarters could count 168 aviation officers including Sperrle.

Sperrle was promoted to ''Oberstleutnant

() is a senior field officer rank in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countries, equivalent to Lieutenant colonel. It is currently used by both the ground and air forces of Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway. The Swedi ...

'' (lieutenant colonel) in 1931 while commanding the 3rd battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment from 1929 to 1933. Sperrle ended his army career in command of the 8th Infantry Regiment, from 1 October 1933 to 1 April 1934. At the rank of ''Oberst

''Oberst'' () is a senior field officer rank in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countries, equivalent to colonel. It is currently used by both the ground and air forces of Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway. The Swedish ...

'' (colonel), Sperrle was given command of the headquarters of the First Air Division (Fliegerdivision 1). Sperrle was given responsibility for coordinating army support aviation. Sperrle's official title was Kommandeur der Heeresflieger (Commander of Army Flyers). After Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

seized power, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

created and Reich Air Ministry. Göring handed most of the squadrons in existence to Sperrle because of his command experiences.

Sperrle was involved in the difficulties in German aircraft procurement. Four months after assuming command, Sperrle was rigorously critical of the Dornier Do 11 and Dornier Do 13 in a conference on 18 July 1934. Five months later, with development failing, Sperrle met with Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of '' Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Born in 1895 into a f ...

, head of aircraft development and ''Luftkreis'' IV commander Alfred Keller, a wartime bomber pilot. It was decided Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German aero ...

production would be a stopgap, while the Dornier Do 23 reached units in the late summer, 1935. The awaited Junkers Ju 86 was scheduled for testing in November 1934 and the promising Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a " wolf in sheep's clothing". Due to restrictions placed on Germany after t ...

in February 1935. Richthofen remarked, "it is better to have second-rate equipment than none at all", though he was responsible for bringing in the next generation of aircraft.

On 1 March 1935, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

announced the existence of the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

. Sperrle was transferred to the Reich Air Ministry. Sperrle was initially given command of ''Luftkreis'' II (Air District II), and then Luftkreis V in Münich upon his promotion to ''Generalmajor

is the Germanic variant of major general, used in a number of Central and Northern European countries.

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

is the second lowest general officer rank in the Royal Danish Army and Royal Danish Air Force. As a two-s ...

'' (Brigadier General) on 1 October 1935. Sperrle remained in Germany until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

. He commanded all German forces in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

from November 1936 to November 1937.

Condor Legion

Sperrle was the first commander of theCondor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

during the Spanish Civil War. The Legion was a corps of German airmen sent to provide support to General Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

who led the Spanish Fascists, known as the Nationalists, against their enemies, the left-wing Republicans. Sperrle was given command of all German forces earmarked for operations in Spain on his appointment. On 1 November 1936 the Legion totalled 4,500 men and by January 1937 the organisation had grown to 6,000 men. The volunteers were interchanged over the course of the conflict, allowing for the maximum number to gain combat experience.

Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of '' Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Born in 1895 into a f ...

was assigned to Sperrle as chief of staff, replacing Alexander Holle

__NOTOC__

Alexander Holle (27 February 1898 – 16 July 1978) was a German general (Generalleutnant) in the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the German involvement in the Spanish Civil War and World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cro ...

. Sperrle needed a highly competent man with a staff officer background. Sperrle had the advantage of knowing Richthofen since the 1920s and thought highly of his chief of staff. Sperrle privately viewed Richthofen as a ruthless snob, and Richthofen disliked his superior's coarse wit and table manners. Professionally, they had few disagreements, and Richthofen's good relationship with Franco encouraged Sperrle to leave day-to-day affairs in his hands.

Sperrle and Richthofen made an effective team in Spain. Sperrle was experienced, intelligent with a good reputation. Richthofen was considered a good combat leader. They combined to advise and oppose Franco to prevent the misuse of their air power. Both men were blunt with the Spanish leader and although the Germans and Spanish did not like each other, they developed a healthy respect which translated into an effective working relationship. Richthofen and Sperrle agreed German support should be limited, for Franco's rule would not be perceived as legitimate if he received lavish foreign aid. Their view was reported to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

.

Sperrle was assisted by the

Sperrle was assisted by the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe

The (; abbreviated OKL) was the high command of the air force () of Nazi Germany.

History

The was organized in a large and diverse structure led by Reich minister and supreme commander of the Air force (german: Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaf ...

(OKL—High Command of the Air Force). Staff officers were trained to solve operational level

In the field of military theory, the operational level of war (also called operational art, as derived from russian: оперативное искусство, or operational warfare) represents the level of command that connects the details of ...

problems and the OKL's reluctance to micromanage gave Sperrle and Richthofen a free hand to devise solutions to tactical and operational problems. An important step was the development of ground-air communication, via the use of frontline signals posts which were in contact with army and airbases simultaneously. Information telephoned to airbases was relayed rapidly by radio to aircraft in flight. This innovation was put into practice during the conflict.

Sperrle left Germany by air on 31 October 1936 and arrived in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, via Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

on 5 November. Sperrle was sent a ''Kampfgruppe'' (bomber group—K/88), ''Jagdgruppe'' 88 (fighter group 88—J/88) and ''Aufklärungsstaffel'' (reconnaissance squadron—AS/88). They were supported by a ''Flak Abteilung'' (F/88) with three heavy and two light batteries with communications, transport and maintenance units. The Germans could not afford to fully equip the Legion, and so the air group made use of Spanish equipment. Of the 1,500 vehicles used, there were 100 types creating a maintenance nightmare. The first mission for the Legion was to airlift

An airlift is the organized delivery of supplies or personnel primarily via military transport aircraft.

Airlifting consists of two distinct types: strategic and tactical. Typically, strategic airlifting involves moving material long distan ...

20,000 men of the African Army. These veterans, once landed, provided a core of battle–hardened veterans.

Spanish Civil War

Sperrle began the war with 120 aircraft, and for the first four months the German aviators failed to make an impact. Sperrle lost 20 percent of his strength in the failed attempt to seize Madrid in 1936. The material support provided was inadequate and left him with just 26 Ju 52s and two Heinkel He 70 aircraft by the end of January 1937. Sperrle's personal leadership and the dedication of senior officers prevented a collapse in morale. The cause of this defeat was the appearance of Soviet-designed and builtPolikarpov I-15

The Polikarpov I-15 (russian: И-15) was a Soviet biplane fighter aircraft of the 1930s. Nicknamed ''Chaika'' (''russian: Чайка'', "Seagull") because of its gulled upper wings,Gunston 1995, p. 299.Green and Swanborough 1979, p. 10. it was ...

and Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 (russian: Поликарпов И-16) is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it was the world's first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to attain o ...

fighter aircraft in the Spanish Republican Air Force

The Spanish Republican Air Force was the air arm of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic, the legally established government of Spain between 1931 and 1939.

Initially divided into two branches: Military Aeronautics ('' Aeronáutica ...

which won air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of com ...

. Bombing raids against Cartagena and Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in ...

, and the Soviet air base at Alcalá de Henares

Alcalá de Henares () is a Spanish city in the Community of Madrid. Straddling the Henares River, it is located to the northeast of the centre of Madrid. , it has a population of 193,751, making it the region's third-most populated municipality ...

, failed. Sperrle personally led an attack against the Republican Navy at Cartagena, sinking two ships. The Republican fleet was forewarned, however, and the majority put to sea and escaped the bombing. Attacks against Madrid, in which 40 tons of bombs were dropped from 19 November 1936, also failed. The bombing and shelling inflicted 1,119 casualties between 14 and 23 November, including 244 dead—303 buildings were hit. The Legion's bomber group temporarily gave up daylight bombing after the failed Fascist offensive.

Sperrle's airmen switched to attacking choke-points around Madrid. Operations were complicated by the Sierra de Guadarrama

The Sierra de Guadarrama (Guadarrama Mountains) is a mountain range forming the main eastern section of the Sistema Central, the system of mountain ranges along the centre of the Iberian Peninsula. It is located between the systems Sierra de G ...

and Sierra de Gredos mountain range. Pilots suffered from circulation problems in non-pressurised cockpits while flying close to the top of the peaks, but only one aircraft and five men were lost to the natural barriers. Influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

outbreaks due to poor living conditions continued to undermine morale. One of the main problems was the inadequate fighter aircraft. The Heinkel He 51

The Heinkel He 51 was a German single-seat biplane which was produced in a number of different versions. It was initially developed as a fighter; a seaplane variant and a ground-attack version were also developed. It was a development of th ...

was not up to the job, Sperrle requested Berlin send modern aircraft. In December three Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

fighters were in Spain, only to return the following February, followed by a single Heinkel He 112 prototype, and Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's ...

dive-bomber. Richthofen travelled to Berlin to secure more of these types in agreement with chief of staff Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' of the Luftwaffe during World War II who was subsequently convicted of war crimes. In a military career that spanned both world wars, Kesselring beca ...

, Ernst Udet

Ernst Udet (26 April 1896 – 17 November 1941) was a German Reich, German pilot during World War I and a ''Luftwaffe'' Colonel-General (''Generaloberst'') during World War II.

Udet joined the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte, Imperial German Ai ...

, and Milch. Sperrle's command began receiving the Dornier Do 17, He 111, Ju 86 bombers and Bf 109 fighters in January 1937. On 1 April 1937 Sperrle was promoted to ''Generalleutnant

is the Germanic variant of lieutenant general, used in some German speaking countries.

Austria

Generalleutnant is the second highest general officer rank in the Austrian Armed Forces (''Bundesheer''), roughly equivalent to the NATO rank of ...

'' (Major General).

The Nationalists turned to destroying the Republican army enclave along the

The Nationalists turned to destroying the Republican army enclave along the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

in the summer, 1937. Sperrle moved his headquarters to Vitoria to lead his small force of 62 aircraft. The Biscay Campaign

The Biscay Campaign ( es, Campaña de Vizcaya) was an offensive of the Spanish Civil War which lasted from 31 March to 1 July 1937. 50,000 men of the Eusko Gudarostea met 65,000 men of the insurgent forces. After heavy combats the Nationalist ...

began on 31 March with the Bombing of Durango. Spanish nationalists reported Republican army movements in the town, but before the bombers arrived they withdrew, leaving the bombers to devastate the town and kill 250 civilians. Sperrle protested to the Nationalists about the "waste of resources", but his own authorised attacks on the town's arms-factory were inaccurate and did just as much to damage the Legion's image. Thereafter Sperrle supported the battle for Otxandio. The Nationalists refused to cooperate in an encirclement operation allowing the defenders to retreat toward Guernica

Guernica (, ), official name (reflecting the Basque language) Gernika (), is a town in the province of Biscay, in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Spain. The town of Guernica is one part (along with neighbouring Lumo) of the m ...

. In a farcical moment Sperrle was arrested on a visit to the front by Nationalist forces as a suspected spy.

Sperrle's staff had no file information on Guernica. Richthofen earmarked the town's Rentaria Bridge for attack, but he seems to have been more interested in Guerricaiz six elms (10 km) south east of Guernica. Richthofen referred to this town as "Guernicaiz" in his diary. The Republican left flank had to retreat through Guernica and the air staff earmarked it for bombing. Richthofen's diary entry, dated 26 April 1937, documented the purpose of the attack. His plan was to block the roads to the south and east of Guernica, thereby offering a chance to encircle and destroy Republican forces.

Later that day, 43 bombers dropped 50 tons of bombs on the town. The bombing has been controversial ever since. The attack, described by some as "terror bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

", was not planned as an attack on the populace and there is no evidence the Germans targeted civilian morale. Guernica acted as an important transportation hub for 23 battalions in positions east of Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

. Two battalions—the 18th Loyala and Saseta—were in the town. The attack prevented the fortification of the Guernica and closed the roads to traffic for 24 hours, preventing Republican forces from evacuating their heavy equipment across the bridge. While there is no evidence civilians were targeted, 300 Spanish people died, and there is no record of any German air commanders expressing sympathy or concern for civilians in the vicinity of a military target. Sperrle was not reprimanded for Guernica.

The Condor Legion supported the Nationaists in the Battle of Bilbao and played a large role in defeating a Republican offensive in the Battle of Brunete, near Madrid. In attacking airfields, using the flak battalion on the front line, and committing the 20 Bf 109 fighters in the fighter escort

The escort fighter was a concept for a fighter aircraft designed to escort bombers to and from their targets. An escort fighter needed range long enough to reach the target, loiter over it for the duration of the raid to defend the bombers, and ...

role the Nationalists gained air superiority over the 400-strong Republican Air Force. The Nationalists destroyed 160 aircraft for the loss of 23. Sperrle's men routed eight battalions of infantry and large numbers of tanks in the close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movemen ...

and interdiction role. From this point on, the Legion possessed general air superiority and the flexibility to transfer rapidly to other fronts to support the land war.

Returning north, In August and September 1937 Sperrle's legion assisted Franco's victory at the Battle of Santander with only 68 aircraft—none of the Brunete losses had been replaced. The Republican reportedly lost 70,000 men captured. For the remainder of September the German command focused on the Asturias Offensive

The Asturias Offensive ( es, Ofensiva de Asturias) was an offensive in Asturias during the Spanish Civil War which lasted from 1 September to 21 October 1937. 45,000 men of the Spanish Republican Army met 90,000 men of the Nationalist forces.

...

which ended the War in the North. Sperrle lost 12 aircraft and 22 men killed, amounting to 17.5 percent of his strength. The attacks, which faced opposition from only 45 Republican aircraft were effective and imposed up to 10 percent losses on some Republican infantry formations. Republican commander Adolfo Prada

Adolfo Prada Vaquero (1883–1962) was a military officer of the Spanish Army. He remained loyal to the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War.

In December 1936, Prada led a division in the Second Battle of the Corunna Road. In Augus ...

later stated the bombing had buried entire units in rubble.

In late 1937, Sperrle fought against the interference of Wilhelm Faupel, one of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's advisors in Spanish affairs. The dispute became so damaging, Hitler removed both men from their positions. Sperrle transferred command of the Condor Legion to ''Generalmajor'' Hellmuth Volkmann and returned to Germany on 30 October. On 1 November 1937 Sperrle was promoted to ''General der Flieger

''General der Flieger'' ( en, General of the aviators) was a General of the branch rank of the Luftwaffe (air force) in Nazi Germany. Until the end of World War II in 1945, this particular general officer rank was on three-star level ( OF-8), e ...

''.

Anschluss and annexation of Czechoslovakia

Sperrle was given command of Luftwaffe Group 3 (Luftwaffengruppenkommando 3) on the 1 February 1938 which eventually became Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet 3) in February 1939. Sperrle commanded the air fleet for the remainder of his military career. Sperrle was used by Hitler in his foreign policy to intimidate small neighbours with the Luftwaffe, which had earned a reputation in Spain. On 12 February 1938, Hitler invited Sperrle to a meeting atBerchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps, south of Berchtesgaden; th ...

with Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian Fatherland Front politician who was the Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Doll ...

, chancellor of the Federal State of Austria

The Federal State of Austria ( de-AT, Bundesstaat Österreich; colloquially known as the , "Corporate State") was a continuation of the First Austrian Republic between 1934 and 1938 when it was a one-party state led by the clerical fascist Fa ...

. Generals Wilhelm Keitel, Walther von Reichenau

Walter Karl Ernst August von Reichenau (8 October 1884 – 17 January 1942) was a field marshal in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II. Reichenau commanded the 6th Army, during the invasions of Belgium and France. During Ope ...

were also in attendance. The meetings eventually helped pave the way for Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

, the Nazi seizure of Austria. The first meeting secured Austrian Nazi Dr Arthur Seyss-Inquart

Arthur Seyss-Inquart (German: Seyß-Inquart, ; 22 July 1892 16 October 1946) was an Austrian Nazi politician who served as Chancellor of Austria in 1938 for two days before the ''Anschluss''. His positions in Nazi Germany included "deputy govern ...

as Interior Minister. When Schuschnig announced a plebiscite on Austrian independence, Hitler ordered Sperrle's Luftkreis V to mobilise for an invasion on 10 March. On 12 March Sperrle's airmen dropped leaflets over Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. All three of Sperrle's combat units, KG 155, KG 255 and JG 153, moved into airfields around Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital ...

and Vienna during the invasion.

On 1 April 1938, Luftwaffengruppenkommando 3 and its subordinate command, Fliegerkommandeure 5, under Major General Ludwig Wolff

Ludwig Wolff (27 September 1857 – 24 February 1919), born in Neustadt in Palatinate, was a German chemist.

He studied chemistry at the University of Strasbourg, where he received his Ph.D. from Rudolph Fittig in 1882. He became Professor ...

, had one Jagdgeschwader (fighter wing), two Kampfgeschwader (bomber wings) and one Sturzkampfgeschwader (Dive-bomber wing). Sperrle's air fleet was used to threaten the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha

Emil Dominik Josef Hácha (12 July 1872 – 27 June 1945) was a Czech lawyer, the president of Czechoslovakia from November 1938 to March 1939. In March 1939, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia, Hácha was the nominal president of the newly pro ...

, into accepting Nazi rule and the formation of Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

. Sperrle possessed 650 aircraft in Fliegerdivision 5, which formed part of his command. His orders were to support the 12th Army in the event an invasion of Czechoslovakia was required. Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' of the Luftwaffe during World War II who was subsequently convicted of war crimes. In a military career that spanned both world wars, Kesselring beca ...

commanding ''Luftwaffengruppenkommando'' 2, was given half of the 2,400 aircraft supporting the invasion and the responsibility of supporting three field armies. The Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

ended the prospect of war and Sperrle's forces landed at Aš

Aš (; german: Asch) is a town in Cheb District in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 12,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Villages of Dolní Paseky, Doubrava, Horní Paseky, Kopaniny, Mokřiny, Nebesa, Nový ...

airfield as the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

annexed the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in October 1938.

In March 1939 Hitler decided to annex Czechoslovakia completely and risk war. He turned once again to the Luftwaffe to assist him achieving diplomatic results. The threat of aerial bombardment proved a crucial in forcing smaller nations to submit to German occupation. The successes confirmed Hitler's view that air power could be used politically, as a "terror weapon". In a series of meetings in Berlin, Hitler told Hácha that half of Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

could be destroyed in two hours, and hundreds of bombers were ready for the operation. Sperrle was asked by Hitler to talk about the Luftwaffe, to intimidate the Czech president. Hácha purportedly fainted, and when he regained consciousness, Göring screamed at him, "think of Prague!"

The elderly President reluctantly ordered the Czechoslovakian Army

The Army of the Czech Republic ( cs, Armáda České republiky, AČR), also known as the Czech Army, is the military service responsible for the defence of the Czech Republic in compliance with international obligations and treaties on collect ...

not to resist. The aerial part of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

was carried out by 500–650 aircraft belonging to Sperrle's newly renamed air fleet, Luftflotte 3. The majority of these aircraft were concentrated in the 4 ''Fliegerdivision'' (4th Flying Division). The operational condition of the Luftwaffe was at 57 percent with 60 percent requiring maintenance, while depots had only enough replacement aero engines to cover 4 to 5 percent of frontline strength. Only 1,432 of the 2,577 aircrew available were fully trained. Just 27 percent of bomber crews were instrument trained. These problems effectively reduced fighter and bomber units to 83 and 32.5 percent of their strength. The Luftwaffe's saving grace was that the British, French and Czech air forces were in slightly worse condition in 1939.

World War II

On 1 September 1939, theWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

invaded Poland prompting the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and France to declare war in her defence. Sperrle's ''Luftflotte'' 3 remained guarding German air space in western Germany and did not contribute to the German invasion, made possible by the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. The air fleet's Order of battle

In modern use, the order of battle of an armed force participating in a military operation or campaign shows the hierarchical organization, command structure, strength, disposition of personnel, and equipment of units and formations of the armed ...

had been stripped of almost all of the combat units it held in March 1939. Only two reconnaissance staffel (squadrons) and a single bomber unit attached to Wekusta 51 remained. Sperrle received the competent Major General Maximilian Ritter von Pohl

__NOTOC__

Maximilian Ritter von Pohl (15 April 1893 – 26 July 1951) was a general in the Luftwaffe during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany.

Awards and decorations

* Knight's Cross of the ...

as his chief of staff. The two men made for a "good partnership". Sperrle was also assigned Major General Walter Surén, appointed as the air fleet's chief signals officer. Surén planned and organised the German field communications for the offensive in 1940. While guarding the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

during the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

, Sperrle's small fleet of 306 aircraft—which included 33 obsolete Arado Ar 68s—fought off probing attacks of French and British aircraft.

Sperrle developed a reputation as gourmet

Gourmet (, ) is a cultural idea associated with the culinary arts of fine food and drink, or haute cuisine, which is characterized by refined, even elaborate preparations and presentations of aesthetically balanced meals of several contrasting, of ...

, whose private transport aircraft featured a refrigerator to keep his wines cool, and although as corpulent as Göring, he was reliable and as ruthless as his superior. Sperrle wanted his air fleet to take a more aggressive stance and won over Göring. On 13 September 1939 he was authorised to undertake long-range high altitude reconnaissance missions at extreme altitudes. Sperrle had already taken the initiative on 4 September when I./KG 53

''Kampfgeschwader'' 53 "Legion Condor" (KG 53; English: ''Condor Legion'') was a Luftwaffe bomber wing during World War II.

Its units participated on all of the fronts in the European Theatre until it was disbanded in May 1945. At all times it ...

carried out such an operation. Photographic operations over France authorised by the OKL began on 21 September, which the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht did not sanction until four days later. Sperrle lost eight aircraft over 21–24 November 1939, but succeeded in obtaining good reconnaissance results. The losses prompted his use of fighter escorts on the return journey. Reconnaissance operations were eased when Sperrle received KG 27

'Kampfgeschwader' 27 ''Boelcke'' was a Luftwaffe medium bomber wing of World War II.

Formed in May 1939, KG 27 first saw action in the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. During the Phoney War—September 1939 – April 1940—th ...

and KG 55

''Kampfgeschwader'' 55 "Greif" (KG 55 or Battle Wing 55) was a Luftwaffe bomber unit during World War II. was one of the longest serving and well-known in the Luftwaffe. The wing operated the Heinkel He 111 exclusively until 1943, when only ...

once the Polish campaign had ended.

Battle of France

''Luftflotte'' 3 was heavily reinforced in the spring, 1940. Sperrle's headquarters was based atBad Orb

Bad Orb (; "Thermae on the Orb River") is a spa town in the Main-Kinzig-Kreis district of Hesse, Germany. It is situated east of Hanau between the forested hills of the Spessart. Bad Orb has a population of over 10,000. Its economy is dominat ...

. The air fleet was assigned I. ''Flakkorps'' under ''Generaloberst

A ("colonel general") was the second-highest general officer rank in the German ''Reichswehr'' and ''Wehrmacht'', the Austro-Hungarian Common Army, the East German National People's Army and in their respective police services. The rank was ...

'' Hubert Weise, I. ''Fliegerkorps'' under ''Generaloberst'' Ulrich Grauert __NOTOC__

Ulrich Grauert (6 March 1889 – 15 May 1941) was a general in the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany during World War II who commanded 1st Air Corps. He was killed on 15 May 1941 when his Junkers Ju 52 aircraft was shot down by F/Lt Jerzy Jank ...

at Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

, the II. ''Fliegerkorps'' under Generaloberst Bruno Loerzer at Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, and V. ''Fliegerkorps'' under command of General Robert Ritter von Greim

Robert ''Ritter'' von Greim (born Robert Greim; 22 June 1892 – 24 May 1945) was a German field marshal and First World War flying ace. In April 1945, in the last days of World War II, Adolf Hitler appointed Greim commander-in-chief of the ''L ...

at Gersthofen. ''Jagdfliegerführer'' 3 (Fighter Flyer Command 3) under the command of Oberst Gerd von Massow was assigned to the air fleet at Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

. Massow was replaced during the campaign by Oberst Werner Junck

Werner Junck (28 December 1895 – 6 August 1976) was a German general in the Luftwaffe during World War II and commander of Fliegerführer Irak. He claimed five aerial victories during World War I.

Origin

Werner Junck was born in Magdeburg, th ...

. For the coming battle, Sperrle had 1,788 aircraft (1,272 operational) at his disposal. Opposing Sperrle, was the ''Armée de l'Air

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: Armée de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Ar ...

'' (French Air Force) eastern (ZOAE) and southern (ZOAS) zones under ''Général de Corps d'armée Aérien'' René Bouscat and Robert Odic. Bouscat had 509 aircraft (363 operational) and Odic 165 (109 combat ready).

I. ''Fliegerkorps'' covered a line running from Eupen

Eupen (, ; ; formerly ) is the capital of German-speaking Community of Belgium and is a city and municipality in the Belgian province of Liège, from the German border ( Aachen), from the Dutch border ( Maastricht) and from the "High Fen ...

, to the Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

border, westward through Fumay

Fumay () is a commune in the Ardennes department in northern France, very close to the Belgian border. The engineer Charles-Hippolyte de Paravey was born in Fumay.

Geography

It is situated in the Meuse valley, the main part of the town be ...

, south of Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The holy district of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held strategic importance. ...

to Senlis and the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/ Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributa ...

at Vernon through to the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

with just 471 aircraft. Cloudy conditions prevented the bomber wings from finding airfields, so industrial targets were attacked instead. II. ''Fliegerkorps'' operated from Bitsch to Revigny, to Villenauxe, then west north of Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Nantes Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

to the (US) and Nantes Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

south of the Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhôn ...

river with only 429 aircraft. V. ''Fliegerkorps'' covered south of this line with 498 aircraft and the 359 fighters of ''Jagdfliegerführer'' 3.

Fall Gelb

(Case Yellow), the invasion of France and the Low Countries

, scope = Strategic

, type =

, location = South-west Netherlands, central Belgium, northern France

, coordinates =

, planned = 1940

, planned_by = Erich von ...

began on 10 May 1940. Sperrle's air fleet engaged in operations supporting ''Generalfeldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

'' Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German field marshal in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Born into a Prussian family with a long military tradition, Rundstedt entered th ...

and Army Group A

Army Group A (Heeresgruppe A) was the name of several German Army Groups during World War II. During the Battle of France, the army group named Army Group A was composed of 45½ divisions, including 7 armored panzer divisions. It was responsibl ...

in the Battle of Belgium

The invasion of Belgium or Belgian campaign (10–28 May 1940), often referred to within Belgium as the 18 Days' Campaign (french: Campagne des 18 jours, nl, Achttiendaagse Veldtocht), formed part of the greater Battle of France, an offensive ...

and Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

, as well as Army Group C. Sperrle's counter-air campaign started badly, reflecting poor photographic interpretation of targets, though he later claimed Luftflotte 3's operations were decisive in achieving air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of com ...

. Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 achieved far greater success. Only 29 of the 42 airfields bombed were being used. Three RAF Advanced Air Striking Force

The RAF Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) comprised the light bombers of 1 Group RAF Bomber Command, which took part in the Battle of France during the Second World War. Before hostilities began, it had been agreed between the United Kingdom a ...

bases were struck. Sperrle's men claimed 240 to 490 aircraft destroyed, mostly "in hangars"—Allied losses were actually 40 first-line aircraft. The penalty for failing to neutralise Allied fighter units cost Sperrle 39 aircraft. Loerzer lost 23—the highest loss of any air corps on the day.

Weiss' Flakkorps repulsed the RAF ASSAF attacks against the German advance, inflicting a 56 percent loss rate. From 10 to 13 May 1940 Sperrle's air fleet was credited with 89 aircraft destroyed in dogfight

A dogfight, or dog fight, is an aerial battle between fighter aircraft conducted at close range. Dogfighting first occurred in Mexico in 1913, shortly after the invention of the airplane. Until at least 1992, it was a component in every majo ...

s, 22 by flak, and 233 to 248 on the ground. The most successful day recorded was on 11 May; 127 aircraft were claimed—100 on the ground and 27 in the air. In a notable incident, 8./ KG 51—one of the air fleet's units, bombed Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as o ...

in error causing 158 civilian casualties and killing 22 children. To cover up the mistake, Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

blamed the British and French for the " Freiburg massacre".

Sperrle's bombers did lay the foundations of a break-through. Loerzer and Grauert's air corps ordered their reconnaissance aircraft to range approximately 400 kilometres into French territory. They avoided the Sedan area so not to attract the attention of the French to German forces advancing on it, they carefully monitored the Allied reactions. Sperrle's air corps commanders targeted air interdiction

Air interdiction (AI), also known as deep air support (DAS), is the use of preventive tactical bombing and strafing by combat aircraft against enemy targets that are not an immediate threat, to delay, disrupt or hinder later enemy engagement of ...

operations and ordered, attacks on rail communications to prevent the westward deployment of the French Army

History

Early history

The first permanent army, paid with regular wages, instead of feudal levies, was established under Charles VII of France, Charles VII in the 1420 to 1430s. The Kings of France needed reliable troops during and after the ...

from the Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the Minister of the Armed Forces (France), French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, F ...

and to pin down Allied reserves by disrupting communications across the Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a ...

. 26 French rail stations were bombed as were 86 localities from 10 to 12 May. Sperrle maintained the pressure on airfields—44 were struck on the 11–12 May. Loerzer and V. ''Fliegerkorps'', under Greim, also bombed road traffic around Charleville-Mézières

or ''Carolomacérienne''

, image flag=Flag of Charleville Mezieres.svg

Charleville-Mézières () is a commune of northern France, capital of the Ardennes department, Grand Est.

Charleville-Mézières is located on the banks of the river Meuse.

...

.

On 13 May, Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist

Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist (8 August 1881 – 13 November 1954) was a German field marshal during World War II. Kleist was the commander of Panzer Group Kleist (later 1st Panzer Army), the first operational formation of several Panzer corps in t ...

's 1st Panzer Army

The 1st Panzer Army (german: 1. Panzerarmee) was a German tank army that was a large armoured formation of the Wehrmacht during World War II.

When originally formed on 1 March 1940, the predecessor of the 1st Panzer Army was named Panzer Gro ...

was poised to cross the Meuse at Montherme, with Heinz Guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (; 17 June 1888 – 14 May 1954) was a German general during World War II who, after the war, became a successful memoirist. An early pioneer and advocate of the "blitzkrieg" approach, he played a central role in th ...

's XIX Army Corps

The XIX Army Corps ( German: ''XIX. Armeekorps'') was an armored corps of the German Wehrmacht between 1 July 1939 and 16 November 1940, when the unit was renamed Panzer Group 2 (German: ''Panzergruppe 2'') and later 2nd Panzer Army (German: ''2 ...

at Sedan. To support the breakthrough, ''Generalleutnant'' Wolfram von Richthofen's VIII. ''Fliegerkorps'' was transferred to ''Luftflotte 3''. Loerzer, supplemented by some of Richthofen's forces, supported Guderian's breakthrough at Sedan. Sperrle arranged a single, massive bombing of the defences; Loerzer did not carry out the plan, but a series of bombing operations on the Meuse front. II. ''Fliegerkorps'' flew 1,770 missions, Richthofen's command flew 360. The bombing played an important role in allowing the breakthrough at Sedan, while Sperrle's fighters repulsed attempts by the Allies to bomb the bridge on 14 May, following their capture. German air defences accounted for 167 bombers destroyed.

During the breakthrough to the English Channel, rail networks were attacked to prevent Allied forces rallying. Greim's V. ''Fliegerkorps'' subjected regrouping French forces to heavy air bombardment. From 13 to 24 May, 174 French rail stations were bombed as were 186 localities, while factories were struck on 35 on occasions and airfields 47 times. Guderian's advance tore through the heart of ZOAN's area and AASF's infrastructure threatening the western airfields of ZOAE. The British abandoned France on 19 May, a day before the German army reached the Channel at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. Sperrle's subordinates, Richthofen and Greim lost 47 reconnaissance aircraft in five days in a bid to find targets.

By this time, Sperrle's boundary with Kesselring ran down the Sambre

The Sambre (; nl, Samber, ) is a river in northern France and in Wallonia, Belgium. It is a left-bank tributary of the Meuse, which it joins in the Wallonian capital Namur.

The source of the Sambre is near Le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in the Ais ...

to Charleroi

Charleroi ( , , ; wa, Tchålerwè ) is a city and a municipality of Wallonia, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. By 1 January 2008, the total population of Charleroi was 201,593.

. Sperrle's job was to protect Guderian's southern flank, though he was ordered to assist against an attempted counter-attack near Arras by supporting the 4th Army advance north. Grauert's I. ''Fliegerkorps'' contributed to 300 sorties

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare ...

over Arras. Loerzer and Greim protected Guderian along the Aisne

Aisne ( , ; ; pcd, Ainne) is a French department in the Hauts-de-France region of northern France. It is named after the river Aisne. In 2019, it had a population of 531,345.2nd and 12th armies. Sperrle's subordinates flew only seven operations against airfields from 20 to 23 May, but 54 against rail stations and another 47 against localities.

Sperrle and Kesselring objected to the halt order during the  Kesselring's air fleet carried the burden of operations over Dunkirk, but Sperrle's men were also attacking shipping. Keller was ordered to destroy Belgian ports in support of the 18th Army, while 30 aircraft from Loerzer's II. ''Fliegerkorps''—including 12 from

Kesselring's air fleet carried the burden of operations over Dunkirk, but Sperrle's men were also attacking shipping. Keller was ordered to destroy Belgian ports in support of the 18th Army, while 30 aircraft from Loerzer's II. ''Fliegerkorps''—including 12 from

The emphasis of German air attacks switched to bombing Fighter Command bases and its infrastructure. On 13 August 1940, Sperrle's air fleet played a role in the failed ''Unternehmen Adlerangriff'' (" Operation Eagle Attack"). As night fell, Sperrle sent ''Kampfgruppe'' 100 (Bombing Group 100) to bomb

The emphasis of German air attacks switched to bombing Fighter Command bases and its infrastructure. On 13 August 1940, Sperrle's air fleet played a role in the failed ''Unternehmen Adlerangriff'' (" Operation Eagle Attack"). As night fell, Sperrle sent ''Kampfgruppe'' 100 (Bombing Group 100) to bomb

Sperrle's airmen flew 4,525 bombing operations in November 1940. The air fleet played a large role in the

Sperrle's airmen flew 4,525 bombing operations in November 1940. The air fleet played a large role in the

The new year of 1942 began with a continuation of the 1941 successes. In February 1942, the battleships '' Scharnhorst'' and '' Gneisenau'' and the cruiser '' Prinz Eugen'' escaped from the French port at Brest in Operation Cerberus upon their return from the recent Operation Berlin. One of Sperrle's former wing commanders, '' General der Jagdflieger''

The new year of 1942 began with a continuation of the 1941 successes. In February 1942, the battleships '' Scharnhorst'' and '' Gneisenau'' and the cruiser '' Prinz Eugen'' escaped from the French port at Brest in Operation Cerberus upon their return from the recent Operation Berlin. One of Sperrle's former wing commanders, '' General der Jagdflieger''

Sperrle's sentiments were delusional. ''Luftflotte'' 3 launched less than 100 sorties including 70 by single-engine fighters. During the evening and night, bombers and anti-shipping squadrons mounted 175 more sorties against the invasion fleet. Sperrle lost 39 aircraft with 21 damaged, 8 due to non-combat causes.