Hugh Lawson White on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

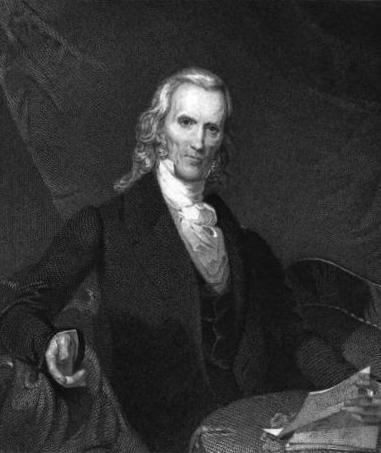

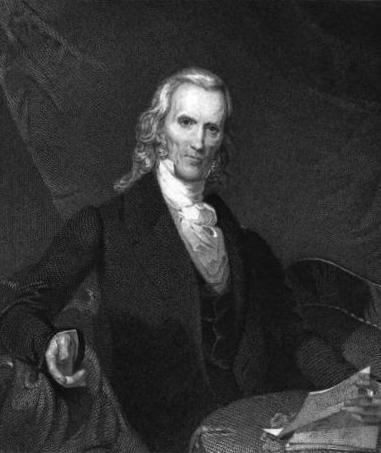

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was a prominent American

A Memoir of Hugh Lawson White

' (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Company, 1856). White fought against the national bank, tariffs, and the use of federal funds for

In 1825, the Tennessee state legislature chose White to replace Andrew Jackson in the United States Senate (Jackson had resigned following his failed run for the presidency in 1824). White spearheaded the Southern states' opposition to sending delegates to 1826

In 1825, the Tennessee state legislature chose White to replace Andrew Jackson in the United States Senate (Jackson had resigned following his failed run for the presidency in 1824). White spearheaded the Southern states' opposition to sending delegates to 1826

Hugh Lawson White

" ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: September 9, 2011. His independent nature and his stern rectitude earned him the appellation "The Cato of the United States." His congressional colleague, Henry Wise, later wrote that White's "patriotism and firmness" as the Senate's president pro tempore was key to resolving the Nullification Crisis. White believed that being on the public payroll obligated him to attend every Senate meeting, no matter the issue.

White's father, James White (1747–1820), was the founder of Knoxville, Tennessee. His brothers-in-law included surveyor

White's father, James White (1747–1820), was the founder of Knoxville, Tennessee. His brothers-in-law included surveyor Our Rich History

, White County, Arkansas website. Retrieved: September 9, 2011.

A memoir of Hugh Lawson White

' – a biography of White written by his granddaughter, Nancy Scott * , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:White, Hugh Lawson 1773 births 1840 deaths People from Iredell County, North Carolina People of colonial North Carolina American people of Scotch-Irish descent Tennessee Democratic-Republicans Jacksonian United States senators from Tennessee Democratic Party United States senators from Tennessee National Republican Party United States senators from Tennessee Whig Party United States senators from Tennessee Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Whig Party (United States) presidential nominees Candidates in the 1836 United States presidential election Tennessee state senators United States Attorneys for the Eastern District of Tennessee Justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court District attorneys in Tennessee Tennessee lawyers American slave owners Politicians from Knoxville, Tennessee United States senators who owned slaves

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, ...

during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder as a Tennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the ultimate judicial tribunal of the state of Tennessee. Roger A. Page is the Chief Justice.

Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state leg ...

justice, he was chosen to succeed former presidential candidate Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

in 1825. He became a member of the new Democratic Party, supporting Jackson's policies and his future presidential administration. However, he left the Democrats in 1836 and was a Whig candidate in that year's presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

.Mary Rothrock, ''The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1972), pp. 501-502.

An ardent strict constructionist

In the United States, strict constructionism is a particular legal philosophy of judicial interpretation that limits or restricts such interpretation only to the exact wording of the law (namely the Constitution).

Strict sense of the term

...

and lifelong states' rights advocate, White was one of President Jackson's most trusted allies in Congress in the late 1820s and early 1830s.Nancy Scott, A Memoir of Hugh Lawson White

' (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Company, 1856). White fought against the national bank, tariffs, and the use of federal funds for

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

, and led efforts in the Senate to pass the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830. In 1833, at the height of the Nullification Crisis, White, as the Senate's president pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase '' pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

, coordinated negotiations over the Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was a ...

.

Suspicious of the growing power of the presidency, White began to distance himself from Jackson in the mid-1830s, and realigned himself with Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

and the burgeoning Whig Party. He was eventually forced out of the Senate when Jackson's allies, led by James K. Polk, gained control of the Tennessee state legislature and demanded his resignation.

Biography

Early life

White was born in what is nowIredell County, North Carolina

Iredell County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 186,693. Its county seat is Statesville, and its largest town is Mooresville. The county was formed in 1788, subtracted from R ...

(but then part of Rowan County), the eldest son of James White and Mary Lawson White. James, a Revolutionary War veteran, moved his family to the Tennessee frontier in the 1780s, and played an active role in the failed State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

.William MacArthur, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), "Knoxville's History: An Interpretation," ''Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976), p. 13. In 1786, he constructed White's Fort

James White's Fort, also known as White's Fort, was an 18th-century settlement that became Knoxville, Tennessee, in the United States. The name also refers to the fort, itself.

The settlement of White's Fort began in 1786 by James White, a mil ...

, which would eventually develop into Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the stat ...

. Young Hugh was a sentinel at the fort and helped manage its small gristmill.

In 1791, White's Fort was chosen as the capital of the newly created Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was admitted to the United States a ...

, and James White's friend, William Blount

William Blount (March 26, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American Founding Father, statesman, farmer and land speculator who signed the United States Constitution. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitutional Convention o ...

, was appointed governor of the territory. Hugh Lawson White worked as Blount's personal secretary, and was tutored by early Knoxville minister and educator, Samuel Carrick

Samuel Czar Carrick (July 17, 1760 – August 17, 1809) was an American Presbyterian minister who was the first president of Blount College, the educational institution to which the University of Tennessee traces its origin. Milton M. KleinUT's ...

. In 1793, he fought in the territorial militia under John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

during the Cherokee–American wars. Historian J. G. M. Ramsey

James Gettys McGready Ramsey (March 25, 1797 – April 11, 1884) was an American historian, physician, planter, slave owner, and businessman, active primarily in East Tennessee during the nineteenth century. Ramsey is perhaps best known for hi ...

credited Hugh Lawson White's company with the killing of the Chickamauga Cherokee

The Chickamauga Cherokee refers to a group that separated from the greater body of the Cherokee during the American Revolutionary War. The majority of the Cherokee people wished to make peace with the Americans near the end of 1776, following se ...

war chief, King Fisher, and White's granddaughter and biographer, Nancy Scott, stated that White fired the fatal shot.

White studied law in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster, ( ; pdc, Lengeschder) is a city in and the county seat of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is one of the oldest inland cities in the United States. With a population at the 2020 census of 58,039, it ranks 11th in population amon ...

, under James Hopkins, and was admitted to the bar in 1796. Two years later, he married Elizabeth Carrick, the daughter of his mentor, Samuel.

The judiciary and early political career

In 1801, White was appointed judge of the Superior Court of Tennessee, then the state's highest court. In 1807, he resigned after being elected to thestate legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

. He left the state legislature in 1809, following his appointment to the state's Court of Errors and Appeals (which replaced the Superior Court as the highest court). He resigned this position in 1815 when he was elected to the state senate. He served in the state senate until 1817. As a state legislator, White helped reform the state's land laws, and engineered the passage of an anti-duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

ing measure.

In 1812, White was named president of the Knoxville branch of the Bank of Tennessee. White was described as a very cautious banker, and his bank was one of the few in the state to survive the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

.

In 1821, President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

appointed White to a commission to settle claims against Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, following the Adams-Onís Treaty in which that nation sold Florida to the United States.

United States Senate

In 1825, the Tennessee state legislature chose White to replace Andrew Jackson in the United States Senate (Jackson had resigned following his failed run for the presidency in 1824). White spearheaded the Southern states' opposition to sending delegates to 1826

In 1825, the Tennessee state legislature chose White to replace Andrew Jackson in the United States Senate (Jackson had resigned following his failed run for the presidency in 1824). White spearheaded the Southern states' opposition to sending delegates to 1826 Congress of Panama

The Congress of Panama (also referred to as the Amphictyonic Congress, in homage to the Amphictyonic League of Ancient Greece) was a congress organized by Simón Bolívar in 1826 with the goal of bringing together the new republics of Latin Americ ...

, which was a general gathering of various nations in the Western Hemisphere, many of which had declared their independence from Spain and abolished slavery. White argued that if the U.S. attended the congress, it would violate the commitment to neutrality put forth by President Washington decades earlier, and stated that the nation should not get involved in foreign treaties merely for the sake of "gratifying national vanity."

Following Jackson's election to the presidency in 1828, White became one of the Jackson Administration's key congressional allies. White was chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, which drew up the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, a major initiative of Jackson. The act called for the relocation of the remaining Native American tribes in the southeastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

and would culminate in the so-called Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

.

In an 1836 speech, White described himself as a "strict constructionist," arguing that the federal government could not pass any laws outside its powers specifically stated in the Constitution. Like many Jacksonians, he was a staunch states' rights, advocate. He opposed the national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

, and rejected federal funding for internal improvements (which he believed only the states had the power to fund). He also supported Jackson's call for the elimination of the Electoral College. A slaveowner himself, he and opposed federal intervention into the issue of slavery.

Like most Southern senators, White opposed the Tariff of 1828

The Tariff of 1828 was a very high protective tariff that became law in the United States in May 1828. It was a bill designed to not pass Congress because it was seen by free trade supporters as hurting both industry and farming, but surprisin ...

, which placed a high tax on goods imported from overseas to protect growing northern industries. White argued that while the federal government had the power to impose tariffs, it should only do so when it benefited the nation as a whole, and not merely one section (i.e., the North) at the expense of another (i.e., the agrarian South, which relied on trade with England). During the resulting Nullification Crisis in late 1832 and early 1833, as the Senate's president pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase '' pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

(the leader of the Senate in the absence of the Vice President), White coordinated negotiations in the interim between the resignation of Vice President John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

(December 28, 1832) and the swearing in of Vice President Martin Van Buren (March 4, 1833). Vice President Calhoun's resignation put White next in line to assume the presidency should that office have become vacant.

1836 presidential election

Toward the end of Jackson's first term, a rift developed between White and Jackson. In 1831, as Jackson reshuffled his cabinet in the aftermath of thePetticoat affair

The Petticoat affair (also known as the Eaton affair) was a political scandal involving members of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet and their wives, from 1829 to 1831. Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, these wome ...

, White was offered the office of Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

but turned it down. During the Nullification Crisis in February 1833, White angered Jackson by appointing Delaware senator and Clay ally John M. Clayton to the select committee to consider the Clay compromise. In later speeches, White stated that the Jackson Administration had drifted away from the party's core states' rights principles, and argued that the executive was gaining too much power.

At the end of Jackson's second term, the Tennessee state legislature endorsed White for the presidency in 1835. This angered Jackson, as he had chosen Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

as his successor. White stated that no sitting president should choose a successor, arguing that doing so was akin to having a monarchy. In 1836, White left Jackson's party entirely, and decided to run for president as a candidate for the Whig Party led by Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

, which had mainly formed from opposition to Jackson but also continued the nationalist agenda of the National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

, although this very contradicting position in regard to White's ideals was not yet determined at that time, as the party was still regionally factionalized.

In the 1836 presidential election, the Whig Party, unable to agree on a candidate, ran four candidates against Van Buren: White, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

, and Willie Person Mangum

Willie Person Mangum (; May 10, 1792September 7, 1861) was a U.S. Senator from the state of North Carolina between 1831 and 1836 and between 1840 and 1853. He was one of the founders and leading members of the Whig party, and was a candidate for ...

. Jackson actively campaigned against White in Tennessee, and accused him of being a federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

who was opposed to states' rights. In spite of this, White won Tennessee, as well as Georgia, giving him 26 electoral votes, the third highest total behind Van Buren's 170 and Harrison's 73.

Later career

By 1837, the relationship between White and Jackson had turned hostile. Jackson was outraged when he learned that White had accused his administration of committing outright fraud, and stated in a letter to Adam Huntsman that White had a "lax code of morals." Jackson's allies such as James K. Polk,Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American politician who served as a congressman and senator from Tennessee as well as the 13th attorney General of the United States.

Biography

Early life

Born in Berkeley Coun ...

, and John Catron

John Catron (January 7, 1786 – May 30, 1865) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1837 to 1865, during the Taney Court.

Early and family life

Little is known of Catron's ...

, also turned against White and blamed him for the dispute with Jackson. White stood by his accusations and blasted Jackson for making "useless expenditures" of public money, and increasing the power of the presidency.

By the late 1830s, Jackson's allies had gained control of the Tennessee state legislature. After White refused their demand that he vote for the Subtreasury Bill, he was forced to resign on January 13, 1840. Following a large banquet in Washington, White returned to his native Knoxville. His entry into the city was marked by the firing of cannons and the ringing of church bells, as he paraded through the streets on horseback.

Shortly after his return, White fell ill, and he died on April 10, 1840. A large funeral procession led his casket and riderless horse

A riderless horse or riderless motorcycle (which may be caparisoned in ornamental and protective coverings, having a detailed protocol of their own) is a single horse or a motorcycle, without a rider, without keys, without a license plate and wit ...

through the streets of Knoxville. He is interred with his family in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery

The First Presbyterian Church Graveyard is the oldest graveyard in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Established in the 1790s, the graveyard contains the graves of some of Knoxville's most prominent early residents, including territorial go ...

.

Personality and style

White believed strongly in the principles of strict constructionism and a limited federal government and voted against fellow Jacksonians if he felt their initiatives ran counter to these principles.Jonathan Atkins,Hugh Lawson White

" ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: September 9, 2011. His independent nature and his stern rectitude earned him the appellation "The Cato of the United States." His congressional colleague, Henry Wise, later wrote that White's "patriotism and firmness" as the Senate's president pro tempore was key to resolving the Nullification Crisis. White believed that being on the public payroll obligated him to attend every Senate meeting, no matter the issue.

Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American politician who served as a congressman and senator from Tennessee as well as the 13th attorney General of the United States.

Biography

Early life

Born in Berkeley Coun ...

recalled that White once departed Knoxville in the middle of a driving snowstorm to ensure he made it to Washington in time for the Senate's fall session. Senator John Milton Niles

John Milton Niles (August 20, 1787 – May 31, 1856) was a lawyer, editor, author and politician from Connecticut, serving in the United States Senate and as United States Postmaster General 1840 to 1841.

Biography

Born in Windsor, Connecticut ...

later wrote that White was often "the only listener to a dull speech." White prided himself on being the most punctual member of the Senate and was usually the first senator to arrive at the Capitol on days when the Senate was in session. Senator Ephraim H. Foster once told a story about waking up well before sunrise one morning, determined to beat White to the Capitol at least once in his career, and arriving only to find White in the committee room analyzing some papers.

Family and legacy

White's father, James White (1747–1820), was the founder of Knoxville, Tennessee. His brothers-in-law included surveyor

White's father, James White (1747–1820), was the founder of Knoxville, Tennessee. His brothers-in-law included surveyor Charles McClung

Charles McClung (May 13, 1761 – August 9, 1835) was an American pioneer, politician, and surveyor best known for drawing up the original plat of Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1791. While Knoxville has since expanded to many times its original s ...

(1761–1835), who platted Knoxville in 1791, Judge John Overton (1766–1833), the co-founder of Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mo ...

, and Senator John Williams

John Towner Williams (born February 8, 1932)Nylund, Rob (15 November 2022)Classic Connection review '' WBOI'' ("For the second time this year, the Fort Wayne Philharmonic honored American composer, conductor, and arranger John Williams, who w ...

(1778–1837). White and his first wife, Elizabeth Carrick, had 12 children, two of whom died in infancy. Between 1825 and 1831, eight of their surviving ten children died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. Their lone surviving son, Samuel (1825–1860), served as mayor of Knoxville in 1857.

White's farm lay just west of Second Creek in Knoxville. In the late 19th century, this became a land development area known as "White's Addition."Don Akchin and Lisa Akchin, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Fort Sanders Historic District, March 4, 1980. The area is now part of the University of Tennessee campus and the Fort Sanders neighborhood. White County, Arkansas

White County is a county located in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2010 census, the population was 77,076. The county seat is Searcy. White County is Arkansas's 31st county, formed on October 23, 1835, from portions of Independence, Ja ...

was also named in his honor., White County, Arkansas website. Retrieved: September 9, 2011.

References

Further reading

* * *External links

*A memoir of Hugh Lawson White

' – a biography of White written by his granddaughter, Nancy Scott * , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:White, Hugh Lawson 1773 births 1840 deaths People from Iredell County, North Carolina People of colonial North Carolina American people of Scotch-Irish descent Tennessee Democratic-Republicans Jacksonian United States senators from Tennessee Democratic Party United States senators from Tennessee National Republican Party United States senators from Tennessee Whig Party United States senators from Tennessee Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Whig Party (United States) presidential nominees Candidates in the 1836 United States presidential election Tennessee state senators United States Attorneys for the Eastern District of Tennessee Justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court District attorneys in Tennessee Tennessee lawyers American slave owners Politicians from Knoxville, Tennessee United States senators who owned slaves