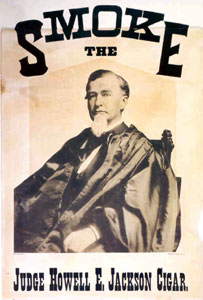

Howell Edmunds Jackson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Howell Edmunds Jackson (April 8, 1832 – August 8, 1895) was an American attorney, politician, and

The 1886 death of Tennessee federal judge John Baxter created a vacancy for President Cleveland to fill on the circuit court for the

The 1886 death of Tennessee federal judge John Baxter created a vacancy for President Cleveland to fill on the circuit court for the

Jackson's brief tenure on the Supreme Court lasted from March 4, 1893 until his death on August 8, 1895. He wrote only forty-six opinions. Because of his poor health and his lack of seniority, many of them were rendered in insignificant cases, especially patent disputes.

Jackson's brief tenure on the Supreme Court lasted from March 4, 1893 until his death on August 8, 1895. He wrote only forty-six opinions. Because of his poor health and his lack of seniority, many of them were rendered in insignificant cases, especially patent disputes.

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 18 ...

from 1893 until his death in 1895. His brief tenure on the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

is most remembered for his opinion in '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'', in which Jackson argued in dissent that a federal income tax was constitutional. Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

appointed Jackson, a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, to the Court. His rulings demonstrated support for broad federal power, a skepticism of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

and an inclination toward judicial restraint

Judicial restraint is a judicial interpretation that recommends favoring the status quo in judicial activities; it is the opposite of judicial activism. Aspects of judicial restraint include the principle of stare decisis (that new decisions s ...

. Jackson's unexpected death after only two years of service prevented him from having a substantial impact on American history.

Born in Paris, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Pari ...

, in 1832, Jackson earned a law degree from Cumberland Law School

Cumberland School of Law is an American Bar Association, ABA accredited law school at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, United States. It was founded in 1847 at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee and is the 11th oldest law schoo ...

and was admitted to the bar in 1856. He briefly practiced law in Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Q ...

before moving to Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

, in 1857. Although he had initially opposed secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

, he took a position in the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

civil service after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

broke out. He returned to the practice of law after the war, but he also took an interest in politics. After an unsuccessful run for the Tennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the ultimate judicial tribunal of the state of Tennessee. Roger A. Page is the Chief Justice.

Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state le ...

, he was elected to a seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives

The Tennessee House of Representatives is the lower house of the Tennessee General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee.

Constitutional requirements

According to the state constitution of 1870, this body is to consis ...

in 1880. When the legislature deadlocked over the selection of a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

, Jackson was selected as a consensus candidate, garnering bipartisan support. Despite being a loyal Democrat, fellow senators of both political parties, including Democrat Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

and Republican Benjamin Harrison, held him in high regard. When Cleveland became president, he appointed Jackson to a seat on the federal circuit court for the Sixth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (in case citations, 6th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* Eastern District of Kentucky

* Western District of K ...

. While on the circuit court, he sided with businesses in a major antitrust dispute and supported an expansive view of constitutional freedoms in a civil rights case.

Shortly after President Harrison – Jackson's former Senate colleague – lost reelection, Supreme Court Justice Lucius Q. C. Lamar

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II (September 17, 1825January 23, 1893) was an American politician, diplomat, and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in both houses of Congress, served as the United States Sec ...

died. Harrison wanted to select a Republican replacement for Lamar, but he realized Democratic senators would likely stall the nomination until he left office. He chose Jackson, whom he viewed both as a close friend and a well-regarded jurist. The Senate unanimously confirmed Jackson just before Harrison left office in 1893. Not long after assuming office, Jackson developed tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, preventing him from playing a major role in Supreme Court affairs. He authored only forty-six opinions, many of which were in patent disputes or other insignificant cases. He left Washington hoping that a better climate would aid his health but returned to the capital after the remaining eight justices split 4–4 in ''Pollock''. Yet Jackson ended up dissenting in the landmark income tax case, likely because of a change in another justice's vote. While Jackson's opinion in ''Pollock'' kept him from total obscurity in the annals of history, the journey to Washington also worsened his health considerably: he died on August 8, 1895, only eleven weeks after the ruling was handed down.

Early life and career

Jackson was born inParis, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Pari ...

, on April 8, 1832. His parents, natives of Virginia, moved to Tennessee in 1827. Jackson's father, Alexander, was a university-trained physician in a time when professional medical training was rare. A Whig, Alexander later served in the Tennessee legislature

The Tennessee General Assembly (TNGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is a part-time bicameral legislature consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The Speaker of the Senate carries the additional title ...

and as mayor of Jackson, Tennessee

Jackson is a city in and the county seat of Madison County, Tennessee, United States. Located east of Memphis, Tennessee, Memphis, it is a regional center of trade for West Tennessee. Its total population was 68,205 as of the 2020 United States ...

. The Jackson family moved to Madison County, Tennessee

Madison County is a county located in the western part of the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 98,823. Its county seat is Jackson. Madison County is included in the Jackson, TN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

H ...

, in 1840. Howell Jackson enrolled at Western Tennessee College, where he studied Greek and Latin. After graduating in 1850, he pursued post-graduate studies at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

for two years. Jackson then read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

with A. W. O. Totten, a justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the ultimate judicial tribunal of the state of Tennessee. Roger A. Page is the Chief Justice.

Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state le ...

, and with attorney and former U.S. Congressman Milton Brown

Milton Brown (September 8, 1903 – April 18, 1936) was an American band leader and vocalist who co-founded the genre of Western swing. His band was the first to fuse hillbilly hokum, jazz, and pop together into a unique, distinctly American hy ...

. He next entered Cumberland Law School

Cumberland School of Law is an American Bar Association, ABA accredited law school at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, United States. It was founded in 1847 at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee and is the 11th oldest law schoo ...

, graduating in 1856 after one year's study. Jackson was admitted to the bar that same year and began practicing law in the town of Jackson. His work there appears to have been largely unsuccessful, and he moved to the larger city of Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

, in 1857. There he established a joint legal practice with David M. Currin, who later served as a Confederate congressman. The firm was successful, and it provided Jackson with experience in corporate litigation.

Tennessee seceded

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

from the Union in 1861. Although Jackson had opposed secession, he supported the Southern side in the war that followed. Judge West H. Humphreys appointed Jackson to enforce Confederate sequestration law in western Tennessee, placing him in charge of confiscating and selling the property of Union loyalists. Extant newspaper accounts show Jackson auctioned off a wide variety of property, including almonds, pickles, chairs, alcohol, tobacco and dried peaches. Just before the Union recaptured Memphis in 1862, Jackson fled with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. He attempted unsuccessfully to secure a position in the Confederate military judiciary. After the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

ended in 1865, Jackson returned to Memphis. Since he had served in the Confederate government, he had to secure a presidential pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

before he could continue the practice of law. Arguing that his role in the Confederate civil service was small, Jackson claimed in his petition that no formal sequestration orders had ever been issued under his tenure. Scholar Terry Calvani

Terry Calvani (born January 29, 1947) is a lawyer, former government official and university professor. Appointed by President Ronald Reagan, he served one term as Commissioner of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. He was also a Member (now "Com ...

has contended these statements in Jackson's application "simply were not true", characterizing them as perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

. President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

initially rejected Jackson's petition, but he granted a second request in 1866.

Since Currin had died during the war, Jackson started a new legal practice with a former colleague. Their clients consisted mainly of banks and other business enterprises. The firm was successful, arguing numerous cases before the Memphis courts. Jackson's political sympathies had by this time moved toward the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. A Redeemer, he was against Reconstruction-era policies and efforts toward racial equality. After his first wife died in 1873, he returned to the town of Jackson, where he started a law practice with General Alexander W. Campbell. Their firm litigated many cases involving property and criminal law. Jackson was well regarded as a lawyer: he sat as a judge on the local courts and served as a law professor at Southwestern Baptist University.

Service in state government

Jackson practiced law in Jackson until 1880. In 1875, however, he was appointed a judge of the temporary Court of Arbitration for Western Tennessee, which heard cases stemming from the large backlog created by the Civil War. When that court was dissolved, Jackson sought the Democratic nomination for a seat on theTennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the ultimate judicial tribunal of the state of Tennessee. Roger A. Page is the Chief Justice.

Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state le ...

, running against incumbent Thomas J. Freeman. At the convention, Jackson lost by a single vote; he refused the entreaties of his supporters to challenge the result. Jackson then became involved in what was then Tennessee's key political dispute: whether to pay back the state debt. Republicans generally supported its repayment, while Democrats were split between a state-credit faction, which was supportive of fulfilling the state's financial obligations and a low-tax faction, which favored repudiating the debt. Jackson, who viewed repudiation to be immoral, was firmly on the state-credit side of this debate. After giving a speech on the debt, he was urged to run for a seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives

The Tennessee House of Representatives is the lower house of the Tennessee General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee.

Constitutional requirements

According to the state constitution of 1870, this body is to consis ...

. Jackson reluctantly agreed, and he was elected in 1880 after a contentious campaign. He was given the chairmanship of the committee on public grounds and buildings, but his prompt elevation to the U.S. Senate prevented him from making any substantial impact in that position.

The legislature's session began in January 1881; the most urgent task before it was the election of a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

. Incumbent Senator James E. Bailey

James Edmund Bailey (August 15, 1822December 29, 1885) was an American United States Democratic Party, Democratic United States Senate, United States Senator from Tennessee from 1877 to 1881.

Early life and education

Bailey was born in Montgome ...

's state-credit policies alienated the low-tax faction of the Democratic caucus, but Republican candidate Horace Maynard

Horace Maynard (August 30, 1814 – May 3, 1882) was an American educator, attorney, politician and diplomat active primarily in the second half of the 19th century. Initially elected to the House of Representatives from Tennessee's 2nd Cong ...

also failed to garner majority support. Jackson, who was considered capable of obtaining bipartisan support, refused to enter the race because he favored Bailey. A week of balloting failed to break the gridlock. Bailey then withdrew from consideration and urged Jackson to enter the race in his stead. On the thirtieth ballot, Republican R. R. Butler announced his support for Jackson, saying he had given up any hope that a Republican would be chosen. The Speaker of the House, a Maynard loyalist, followed suit, arguing that Jackson was the best choice among the Democrats. A number of Democrat legislators, many of whom were afraid that a Republican could be elected if they did not unite behind a candidate, backed Jackson as well. Convinced by Butler, other Republicans did the same, and Jackson was elected, receiving sixty-eight votes of the ninety-eight cast.

Senate tenure

Jackson took his seat in the Senate on March 4, 1881. He was a member of four committees: thePost Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional serv ...

, Pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

, Claims

Claim may refer to:

* Claim (legal)

* Claim of Right Act 1689

* Claims-based identity

* Claim (philosophy)

* Land claim

* A ''main contention'', see conclusion of law

* Patent claim

* The assertion of a proposition; see Douglas N. Walton

* A righ ...

, and Judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

panels. Despite his loyalty to the Democratic platform, Republicans and Democrats alike held him in high regard. In the Senate, Jackson advocated for civil service reform and for the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminat ...

. He supported further restrictions on Chinese immigration and argued for lower tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s and higher infrastructure spending. Jackson's views on legal issues were influential among his colleagues: many important bills on the judiciary were referred to the subcommittee on which he sat. More important than his legislative accomplishments, however, were the personal relationships that he forged. Jackson became a friend of President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, whose tariff policies he supported. He also established a friendly relationship with his colleague Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, whom he was seated next to on the Senate floor. Jackson held a reputation for being a hard-working and committed legislator.

Circuit judge

The 1886 death of Tennessee federal judge John Baxter created a vacancy for President Cleveland to fill on the circuit court for the

The 1886 death of Tennessee federal judge John Baxter created a vacancy for President Cleveland to fill on the circuit court for the Sixth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (in case citations, 6th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* Eastern District of Kentucky

* Western District of K ...

. Cleveland asked his friend Jackson, who was still serving in the Senate, to recommend potential replacements, but the President ignored his advice and instead offered the seat to him. The senator attempted to decline, but Cleveland's insistence eventually led him to agree to be nominated. The Senate unanimously confirmed Jackson. During his seven-year tenure, he heard a variety of cases, a number of which pertained to patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

issues. In 1889, Jackson urged his friend Harrison – who by then had become president – to appoint his judicial colleague Henry Billings Brown

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown ...

to the Supreme Court; although Harrison declined to appoint Brown that year, he elevated him to fill a subsequent vacancy the next year. Jackson's most noteworthy opinion on the circuit court was ''In re Greene'' (1892), the first case in which a federal court applied the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

Th ...

. The ruling in ''Greene'' rejected a Sherman Act indictment against whiskey producers on the basis that the defendants were not preventing other firms from entering the whiskey market. Jackson's narrow interpretation of the Act set the stage for later consequential antitrust cases, including ''United States v. E. C. Knight Co.

''United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'', 156 U.S. 1 (1895), also known as the "Sugar Trust Case," was a List of United States Supreme Court cases, United States Supreme Court United States antitrust law, antitrust case that severely limited the fede ...

'' (1895), and it continued to influence interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among ...

law for half a century.

In other cases, Jackson took a broader view of constitutional provisions. His 1893 ruling in ''United States v. Patrick'' interpreted the Civil Rights Act of 1870 expansively. The defendants in ''Patrick'', who were residents of Tennessee, had been charged with killing several federal officers while they were searching for an illegal still

A still is an apparatus used to distill liquid mixtures by heating to selectively boil and then cooling to condense the vapor. A still uses the same concepts as a basic distillation apparatus, but on a much larger scale. Stills have been used ...

. A lower federal court threw out the indictments, holding the officers were not exercising any legally protected civil right while they were carrying out their duties. Jackson rejected these arguments. In his view, federal officers have a constitutionally protected right "of accepting the public employment, and engaging in the administration of its functions". On that basis, Jackson concluded the prosecution under the Civil Rights Act could go forward since the officers' civil rights had been violated. Some Southerners denounced the ruling, objecting that it expanded the scope of an already loathed law. Jackson's decision also showed that his stances were sufficiently moderate to coalesce with the Republican agenda.

Supreme Court nomination

On January 23, 1893, Supreme Court JusticeLucius Q. C. Lamar

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II (September 17, 1825January 23, 1893) was an American politician, diplomat, and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in both houses of Congress, served as the United States Sec ...

died. At this point, President Harrison was a lame duck: Grover Cleveland had won the 1892 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1892.

{{TOC right

Asia Japan

* 1892 Japanese general election

Europe Denmark

* 1892 Danish Folketing election

Portugal

* 1892 Portuguese legislative election

United Kingdom

* 1892 Chelmsford by-el ...

and would take office in six weeks. Although Harrison wanted to appoint a fellow Republican to fill the vacancy, he recognized that the Democrat-controlled Senate would likely refuse to act on the nomination since it could simply wait for Cleveland to make a more favorable appointment. Not long after Lamar's death, Justice Brown, whom Jackson had recommended to Harrison a few years prior, paid a visit to the White House. Wishing to return the favor, the Republican Brown suggested that the Democratic Jackson would be an ideal candidate for Harrison to select. Jackson indeed checked all the boxes for Harrison: he was a conservative and well-regarded jurist and came from the South, as Lamar had. The two had also served in the Senate together and were close friends. Harrison agreed to nominate Jackson, doing so on February 2. The decision surprised both Republicans and Democrats, who expected Harrison to choose someone from his own party. Jackson's nomination was held up initially in committee, but senators unanimously confirmed their ex-colleague on February 18. Most had expected some objections on the floor, and a contemporaneous ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' report noted that many were left "wondering...what became of the opposition". Professor Richard D. Friedman concludes their acquiescence was understandable: Democrats "could not very well vote against one of their own", while "Republicans, after initial disgruntlement, understood the logic of Harrison's move." Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

swore in Jackson on the morning of March 4, just hours before administering the presidential oath to Harrison's successor.

Supreme Court service

Jackson's brief tenure on the Supreme Court lasted from March 4, 1893 until his death on August 8, 1895. He wrote only forty-six opinions. Because of his poor health and his lack of seniority, many of them were rendered in insignificant cases, especially patent disputes.

Jackson's brief tenure on the Supreme Court lasted from March 4, 1893 until his death on August 8, 1895. He wrote only forty-six opinions. Because of his poor health and his lack of seniority, many of them were rendered in insignificant cases, especially patent disputes.

''Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.''

Scholar Irving Schiffman maintains that Jackson's name would have been "buried in hecoffin of historical neglect" were it not for his participation in a single case: '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'' ''Pollock'' involved a challenge to a provision of the 1894Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act

The Revenue Act or Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894 (ch. 349, §73, , August 27, 1894) slightly reduced the United States tariff rates from the numbers set in the 1890 McKinley tariff and imposed a 2% tax on income over $4,000. It is named for Wi ...

, that had imposed a two percent personal income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Ta ...

on all revenue over four thousand dollars. According to the plaintiff, the law imposed a direct tax

Although the actual definitions vary between jurisdictions, in general, a direct tax or income tax is a tax imposed upon a person or property as distinct from a tax imposed upon a transaction, which is described as an indirect tax. There is a dis ...

without apportioning it among the states, in violation of a provision of the Constitution. In practice, it would be impossible to apportion such taxes among the states, so a ruling on that basis would doom all federal income taxation. Jackson was ill, but the eight remaining justices heard the case. They struck down certain other provisions of the act but split 4–4 on the constitutionality of the income tax. When Jackson suggested he could return to Washington, the Court agreed to rehear the case to make a more conclusive ruling on the income tax's legality.

Because the other eight justices had been evenly split, it was assumed that Jackson's vote would determine the case. Experts were uncertain how he would rule: his Southern background suggested he might support the tax, but his pro-business judicial views meant he might be inclined to strike it down. During the three days of arguments, lawyers aimed their contentions at the violently coughing Jackson, often ignoring other justices in their zeal to persuade the swing vote. But when the ruling finally came down on May 20, 1895, Jackson was in dissent. A five-justice majority led by Chief Justice Fuller ruled the tax to be unconstitutional, declaring it was an impermissible unapportioned direct tax. Jackson joined Brown and justices John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his ...

and Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1844 – May 19, 1921) was an American politician and jurist from Louisiana. White was a U.S. Supreme Court justice for 27 years, first as an associate justice from 1894 to 1910, then as the ninth chief ju ...

in dissenting from the Court's holding. In an impassioned opinion, he wrote "this decision is, in my judgment, the most disastrous blow ever struck at the constitutional power of Congress". Numerous coughing fits interrupted Jackson's ardent turns of phrase, stopping the seriously ill justice several times during his forty-five-minute delivery of the dissent.

Many have attempted to determine how Jackson ended up in the minority. The apparent reason is that one justice switched his vote. Newspapers at the time identified George Shiras as the "vacillating Justice"; biographer Willard King notes that "great obloquy (verbal abuse) was heaped on him" by outlets that opposed the Court's decision. While this suggestion continues to have its adherents, three sources denied Shiras's vote changed. Others have argued that Horace Gray

Horace Gray (March 24, 1828 – September 15, 1902) was an American jurist who served on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and then on the United States Supreme Court, where he frequently interpreted the Constitution in ways that increa ...

or David Brewer changed their votes, but those proposals are difficult to reconcile with primary sources. The remaining possibility is that no justice changed his vote. According to this theory, five justices were averse to the tax from the beginning, but they were unable to unite behind one legal theory initially. Jackson's dissent eventually won vindication from the court of history: the Sixteenth Amendment passed eighteen years after ''Pollock'' revised the Constitution to authorize an income tax.

Other cases

History has taken little notice of most of Jackson's remaining opinions. He was assigned to write a number of opinions involving patent law, a field with which his circuit court tenure had given him experience. A disproportionate number of his rulings drew no dissents, suggesting they were mostly insignificant. His poor health and the fact that he was one of the newest justices for the entirety of his brief tenure likely contributed to this. Jackson's few cases display support for the proposition that the judiciary should defer to the legislature. His opinions in '' Schurz v. Cook'' (1893) and ''Columbus Southern Railway v. Wright

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

'' (1894) rejected attempts by corporations to strike down various tax laws. Jackson's opinions also evidence both his support for broad federal power and his skepticism of states' decisions. In '' Mobile & Ohio R.R. v. Tennessee'' (1894), he favored a broad interpretation of the Contract Clause

Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution, known as the Contract Clause, imposes certain prohibitions on the states. These prohibitions are meant to protect individuals from intrusion by state governments and to keep ...

, ruling over four dissenting votes that Tennessee acted illegally in using its state constitution to renege on a promised tax exemption for a railroad company. In the 1893 case of ''Brass v. North Dakota

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

'', meanwhile, he exhibited support for the concept of substantive due process

Substantive due process is a principle in United States constitutional law that allows courts to establish and protect certain fundamental rights from government interference, even if only procedural protections are present or the rights are unen ...

, joining a dissent by Justice Brewer that argued that a North Dakota regulation of grain elevator

A grain elevator is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lower level and deposits ...

s was an unconstitutional infringement upon the freedom of contract

Freedom of contract is the process in which individuals and groups form contracts without government restrictions. This is opposed to government regulations such as minimum-wage laws, competition laws, economic sanctions, restrictions on pri ...

. Finally, he joined a five-justice majority in ''Fong Yue Ting v. United States

''Fong Yue Ting v. United States'', 149 U.S. 698 (1893), decided by the United States Supreme Court on May 15, 1893, was a case challenging provisions in Section 6 of the Geary Act of 1892 that extended and amended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 188 ...

'' (1893) to hold the federal government could deport Chinese immigrant laborers without providing them with due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

protections.

Illness and death

Despite being apparently healthy at the time of his nomination, Jackson developedtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

within a year of taking the bench. He returned quickly to his duties, but his illness worsened, and he had to leave the capital. In October 1894, he journeyed to the West hoping the climate would improve his condition. He traveled to Thomasville, Georgia

Thomasville is the county seat of Thomas County, Georgia, United States. The population was 18,413 at the 2010 United States Census, making it the second largest city in southwest Georgia after Albany, Georgia, Albany.

The city deems itself the "C ...

, a few months later; his lung ailment started improving, but his health deteriorated substantially when he was afflicted with dropsy

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

. Having no independent source of income, Jackson could not retire without a special act of Congress giving him a pension. Being too unwell to participate, he was unable to cast a vote in the consequential cases of ''United States v. E. C. Knight Co.

''United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'', 156 U.S. 1 (1895), also known as the "Sugar Trust Case," was a List of United States Supreme Court cases, United States Supreme Court United States antitrust law, antitrust case that severely limited the fede ...

'' and ''In re Debs

''In re Debs'', 158 U.S. 564 (1895), was a US labor law case of the United States Supreme Court decision handed down concerning Eugene V. Debs and labor unions.

Background

Eugene V. Debs, president of the American Railway Union, had been involve ...

''. Jackson returned to his Tennessee home in February; his health began improving, and he expressed the hope that he would be able to return to his judicial duties by fall. His desire to participate in the income tax case led him to return to Washington in May, earlier than he had anticipated. The journey did substantial harm to Jackson's health, and Schiffman notes that his failure in ''Pollock'' "provided little incentive with which to uplift the spirit beyond the pains of the body". He died in Nashville just eleven weeks after the decision was rendered; his remains were buried in that city's Mount Olivet Cemetery. His tenure on the Supreme Court had lasted for less than two and a half years.

Personal life

Jackson married Sophie Malloy, a Memphis banker's daughter, in 1859. They had six children (two of whom died during infancy) before her death in 1873. He then married Mary Harding, the daughter of influential Tennessee resident W. G. Harding, the following year. Jackson's brotherWilliam Hicks Jackson

William Hicks "Red" Jackson (October 1, 1835 – March 30, 1903) was a career United States Army officer who graduated from West Point. After serving briefly in the Southwest and resigning when the American Civil War broke out, he served in th ...

, who had been a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

during the Civil War, was married to another of Harding's daughters. When Harding died in 1886, the two Jackson brothers and their wives inherited the Belle Meade Plantation

Belle Meade Historic Site and Winery, located in Belle Meade, Tennessee, is a historic mansion that is now operated as an attraction, museum, winery, and onsite restaurant together with outbuildings on its 30 acres of property. In the late 19th ...

, where thoroughbred horses

The Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed. Thoroughbreds are con ...

were raised. Howell's role was minimal, and he sold his stake in the horses to his brother in 1890. His thousand acres of property at West Meade (another part of Harding's estate) contained his home, which was considered among the finest in the state. Jackson had three children with his second wife. He was a devout Christian, serving as an elder of the First Presbyterian Church of Nashville. His hobbies included hunting foxes and watching horse races

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic pr ...

.

Legacy

Jackson's impact on history was minimal, due in no small part to the brevity of his Supreme Court tenure. A 1972 survey of legal scholars found Jackson was considered a "below average" justice, although the respondents declined to classify him as a "failure". His participation in ''Pollock'', however, prevented him from being entirely covered with what Schiffman called the "shroud of anonymity". ''Pollock'' was among the leading cases of the era, and his vote aligned with later public sentiment. While Jackson was well regarded by his contemporaries, Timothy L. Hall writes that he "would probably never have been a great Supreme Court justice"; according to Hall, the "plodding and pedestrian" Jackson "was capable of solid work but not of judicial brilliance". Scholar Roger D. Hardaway, while conceding that the justice "is not a giant" in the annals of the Supreme Court, argues that Jackson's accomplished if brief work deserves a prominent place in Tennessee history. TheLiberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Mass ...

was named in his honor.

See also

*List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight Associate Justice of the Supreme ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jackson, Howell Edmunds 1832 births 1895 deaths 19th-century American judges 19th-century American politicians Cumberland School of Law alumni Democratic Party United States senators from Tennessee Judges of the United States circuit courts Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit Democratic Party members of the Tennessee House of Representatives Tennessee lawyers Union University alumni United States federal judges appointed by Benjamin Harrison United States federal judges appointed by Grover Cleveland Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States University of Virginia alumni People from Paris, Tennessee Burials at Mount Olivet Cemetery (Nashville) 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis Tuberculosis deaths in Tennessee