Homo neandertalensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

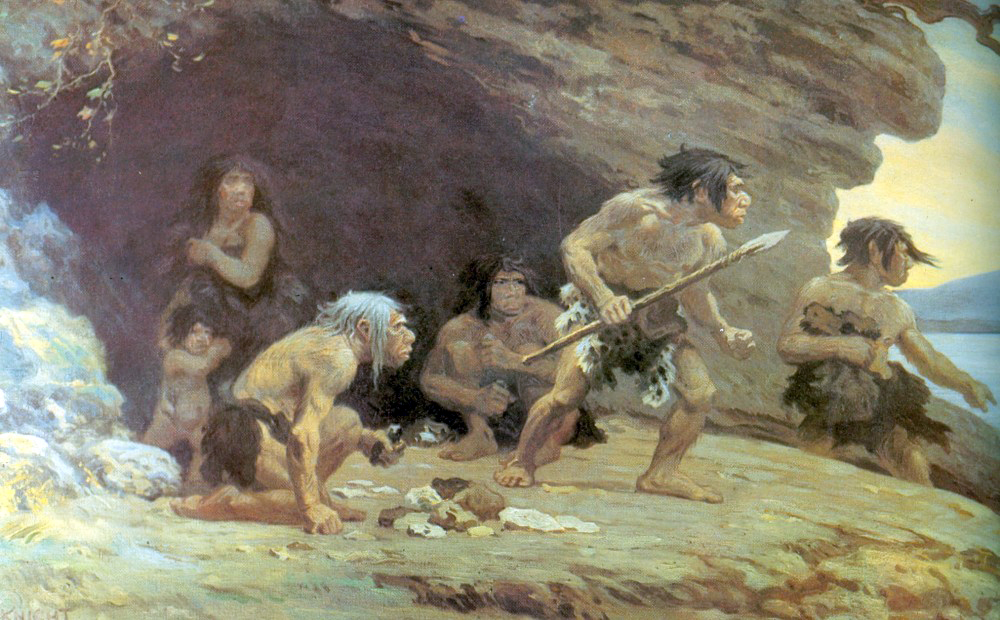

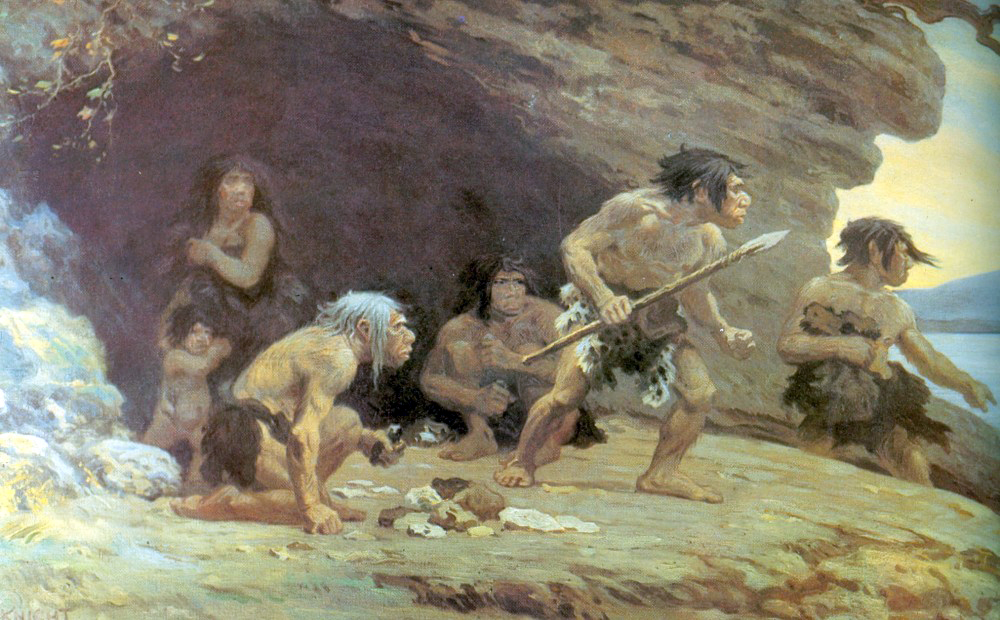

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an

Neanderthals are named after the Neandertal Valley in which the first identified specimen was found. The valley was spelled ''Neanderthal'' and the species was spelled ''Neanderthaler'' in

Neanderthals are named after the Neandertal Valley in which the first identified specimen was found. The valley was spelled ''Neanderthal'' and the species was spelled ''Neanderthaler'' in

By the early 20th century, numerous other Neanderthal discoveries were made, establishing ''H. neanderthalensis'' as a legitimate species. The most influential specimen was

By the early 20th century, numerous other Neanderthal discoveries were made, establishing ''H. neanderthalensis'' as a legitimate species. The most influential specimen was  By the middle of the century, based on the exposure of Piltdown Man as a hoax as well as a reexamination of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 (who had

By the middle of the century, based on the exposure of Piltdown Man as a hoax as well as a reexamination of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 (who had

Pre- and early Neanderthals, living before the Eemian interglacial (130,000 years ago), are poorly known and come mostly from Western European sites. From 130,000 years ago onwards, the quality of the fossil record increases dramatically with classic Neanderthals, who are recorded from Western, Central, Eastern, and Mediterranean Europe, as well as

Pre- and early Neanderthals, living before the Eemian interglacial (130,000 years ago), are poorly known and come mostly from Western European sites. From 130,000 years ago onwards, the quality of the fossil record increases dramatically with classic Neanderthals, who are recorded from Western, Central, Eastern, and Mediterranean Europe, as well as

Neanderthals had a staightened chin, sloping forehead, and projecting nose, which also started somewhat higher on the face than in most modern humans. The Neanderthal skull is typically more elongated and less globular than that of most modern humans, and features much more of an

Neanderthals had a staightened chin, sloping forehead, and projecting nose, which also started somewhat higher on the face than in most modern humans. The Neanderthal skull is typically more elongated and less globular than that of most modern humans, and features much more of an

Low population caused a low genetic diversity and probably inbreeding, which reduced the population's ability to filter out harmful mutations (inbreeding depression). However, it is unknown how this affected a single Neanderthal's genetic burden and, thus, if this caused a higher rate of birth defects than in modern humans. It is known, however, that the 13 inhabitants of Sidrón Cave collectively exhibited 17 different birth defects likely due to inbreeding or genetic disorder, recessive disorders. Likely due to advanced age (60s or 70s), La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 had signs of Baastrup's disease, affecting the spine, and osteoarthritis. Shanidar 1, who likely died at about 30 or 40, was diagnosed with the most ancient case of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), a degenerative disease which can restrict movement, which, if correct, would indicate a moderately high incident rate for older Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were subject to several infectious diseases and parasites. Modern humans likely transmitted diseases to them; one possible candidate is the stomach bacteria ''Helicobacter pylori''. The modern human papillomavirus infection, human papillomavirus variant 16A may descend from Neanderthal introgression. A Neanderthal at Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, shows evidence of a gastrointestinal ''Enterocytozoon bieneusi'' infection. The leg bones of the French La Ferrassie 1 feature lesions that are consistent with periostitis—inflammation of the tissue enveloping the bone—likely a result of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, which is primarily caused by a chest infection or lung cancer. Neanderthals had a lower tooth decay, cavity rate than modern humans, despite some populations consuming typically cavity-causing foods in great quantity, which could indicate a lack of cavity-causing oral bacteria, namely ''Streptococcus mutans''.

Two 250,000-year-old Neanderthaloid children from Payré, France, present the earliest known cases of lead exposure of any hominin. They were exposed on two distinct occasions either by eating or drinking contaminated food or water, or inhaling lead-laced smoke from a fire. There are two lead mines within of the site.

Low population caused a low genetic diversity and probably inbreeding, which reduced the population's ability to filter out harmful mutations (inbreeding depression). However, it is unknown how this affected a single Neanderthal's genetic burden and, thus, if this caused a higher rate of birth defects than in modern humans. It is known, however, that the 13 inhabitants of Sidrón Cave collectively exhibited 17 different birth defects likely due to inbreeding or genetic disorder, recessive disorders. Likely due to advanced age (60s or 70s), La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 had signs of Baastrup's disease, affecting the spine, and osteoarthritis. Shanidar 1, who likely died at about 30 or 40, was diagnosed with the most ancient case of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), a degenerative disease which can restrict movement, which, if correct, would indicate a moderately high incident rate for older Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were subject to several infectious diseases and parasites. Modern humans likely transmitted diseases to them; one possible candidate is the stomach bacteria ''Helicobacter pylori''. The modern human papillomavirus infection, human papillomavirus variant 16A may descend from Neanderthal introgression. A Neanderthal at Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, shows evidence of a gastrointestinal ''Enterocytozoon bieneusi'' infection. The leg bones of the French La Ferrassie 1 feature lesions that are consistent with periostitis—inflammation of the tissue enveloping the bone—likely a result of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, which is primarily caused by a chest infection or lung cancer. Neanderthals had a lower tooth decay, cavity rate than modern humans, despite some populations consuming typically cavity-causing foods in great quantity, which could indicate a lack of cavity-causing oral bacteria, namely ''Streptococcus mutans''.

Two 250,000-year-old Neanderthaloid children from Payré, France, present the earliest known cases of lead exposure of any hominin. They were exposed on two distinct occasions either by eating or drinking contaminated food or water, or inhaling lead-laced smoke from a fire. There are two lead mines within of the site.

Neanderthals likely lived in more sparsely distributed groups than contemporary modern humans, but group size is thought to have averaged 10 to 30 individuals, similar to modern hunter-gatherers. Reliable evidence of Neanderthal group composition comes from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, and the footprints at Le Rozel, France: the former shows 7 adults, 3 adolescents, 2 juveniles, and an infant; whereas the latter, based on footprint size, shows a group of 10 to 13 members where juveniles and adolescents made up 90%.

A Neanderthal child's teeth analysed in 2018 showed it was weaned after 2.5 years, similar to modern hunter gatherers, and was born in the spring, which is consistent with modern humans and other mammals whose birth cycles coincide with environmental cycles. Indicated from various ailments resulting from high stress at a low age, such as stunted growth, British archaeologist Paul Pettitt hypothesised that children of both sexes were put to work directly after weaning; and Trinkaus said that, upon reaching adolescence, an individual may have been expected to join in hunting large and dangerous game. However, the bone trauma is comparable to modern Inuit, which could suggest a similar childhood between Neanderthals and contemporary modern humans. Further, such stunting may have also resulted from harsh winters and bouts of low food resources.

Sites showing evidence of no more than three individuals may have represented nuclear families or temporary camping sites for special task groups (such as a hunting party). Bands likely moved between certain caves depending on the season, indicated by remains of seasonal materials such as certain foods, and returned to the same locations generation after generation. Some sites may have been used for over 100 years. Cave bears may have greatly competed with Neanderthals for cave space, and there is a decline in cave bear populations starting 50,000 years ago onwards (although their extinction occurred well after Neanderthals had died out). Although Neanderthals are generally considered to have been cave dwellers, with 'home base' being a cave, open-air settlements near contemporaneously inhabited cave systems in the Levant could indicate mobility between cave and open-air bases in this area. Evidence for long-term open-air settlements is known from the 'Ein Qashish site in Israel, and Moldova I in Ukraine. Although Neanderthals appear to have had the ability to inhabit a range of environments—including plains and plateaux—open-air Neanderthals sites are generally interpreted as having been used as slaughtering and butchering grounds rather than living spaces.

In 2022, remains of the first-known Neanderthal family (six adults and five children) were excavated from Chagyrskaya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia in Russia. The family, which included a father, a daughter, and what appear to be cousins, most likely died together, presumably from starvation.

Neanderthals likely lived in more sparsely distributed groups than contemporary modern humans, but group size is thought to have averaged 10 to 30 individuals, similar to modern hunter-gatherers. Reliable evidence of Neanderthal group composition comes from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, and the footprints at Le Rozel, France: the former shows 7 adults, 3 adolescents, 2 juveniles, and an infant; whereas the latter, based on footprint size, shows a group of 10 to 13 members where juveniles and adolescents made up 90%.

A Neanderthal child's teeth analysed in 2018 showed it was weaned after 2.5 years, similar to modern hunter gatherers, and was born in the spring, which is consistent with modern humans and other mammals whose birth cycles coincide with environmental cycles. Indicated from various ailments resulting from high stress at a low age, such as stunted growth, British archaeologist Paul Pettitt hypothesised that children of both sexes were put to work directly after weaning; and Trinkaus said that, upon reaching adolescence, an individual may have been expected to join in hunting large and dangerous game. However, the bone trauma is comparable to modern Inuit, which could suggest a similar childhood between Neanderthals and contemporary modern humans. Further, such stunting may have also resulted from harsh winters and bouts of low food resources.

Sites showing evidence of no more than three individuals may have represented nuclear families or temporary camping sites for special task groups (such as a hunting party). Bands likely moved between certain caves depending on the season, indicated by remains of seasonal materials such as certain foods, and returned to the same locations generation after generation. Some sites may have been used for over 100 years. Cave bears may have greatly competed with Neanderthals for cave space, and there is a decline in cave bear populations starting 50,000 years ago onwards (although their extinction occurred well after Neanderthals had died out). Although Neanderthals are generally considered to have been cave dwellers, with 'home base' being a cave, open-air settlements near contemporaneously inhabited cave systems in the Levant could indicate mobility between cave and open-air bases in this area. Evidence for long-term open-air settlements is known from the 'Ein Qashish site in Israel, and Moldova I in Ukraine. Although Neanderthals appear to have had the ability to inhabit a range of environments—including plains and plateaux—open-air Neanderthals sites are generally interpreted as having been used as slaughtering and butchering grounds rather than living spaces.

In 2022, remains of the first-known Neanderthal family (six adults and five children) were excavated from Chagyrskaya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia in Russia. The family, which included a father, a daughter, and what appear to be cousins, most likely died together, presumably from starvation.

Genetic analysis indicates there were at least 3 distinct geographical groups—Western Europe, the Mediterranean coast, and east of the Caucasus—with some migration among these regions. Post-Eemian Western European

Genetic analysis indicates there were at least 3 distinct geographical groups—Western Europe, the Mediterranean coast, and east of the Caucasus—with some migration among these regions. Post-Eemian Western European

Neanderthals were once thought of as scavengers, but are now considered to have been

Neanderthals were once thought of as scavengers, but are now considered to have been

At Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, Neanderthals likely cooked and possibly smoking (cooking), smoked food, as well as used certain plants—such as yarrow and camomile—as flavouring, although these plants may have instead been used for their medicinal properties. At Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, Neanderthals may have been roasting pinecones to access pine nuts.

At Grotte du Lazaret, France, a total of 23 red deer, 6 ibexes, 3 aurochs, and 1 roe deer appear to have been hunted in a single autumn hunting season, when strong male and female deer herds would group together for rut (mammalian reproduction), rut. The entire carcasses seem to have been transported to the cave and then butchered. Because this is such a large amount of food to consume before spoilage, it is possible these Neanderthals were curing (food preservation), curing and preserving it before winter set in. At 160,000 years old, it is the oldest potential evidence of food storage. The great quantities of meat and fat which could have been gathered in general from typical prey items (namely mammoths) could also indicate food storage capability. With shellfish, Neanderthals needed to eat, cook, or in some manner preserve them soon after collection, as shellfish spoils very quickly. At Cave of Los Aviones, Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the remains of edible, algae eater, algae eating shellfish associated with the alga ''Jania rubens'' could indicate that, like some modern hunter gatherer societies, harvested shellfish were held in water-soaked algae to keep them alive and fresh until consumption.

At Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, Neanderthals likely cooked and possibly smoking (cooking), smoked food, as well as used certain plants—such as yarrow and camomile—as flavouring, although these plants may have instead been used for their medicinal properties. At Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, Neanderthals may have been roasting pinecones to access pine nuts.

At Grotte du Lazaret, France, a total of 23 red deer, 6 ibexes, 3 aurochs, and 1 roe deer appear to have been hunted in a single autumn hunting season, when strong male and female deer herds would group together for rut (mammalian reproduction), rut. The entire carcasses seem to have been transported to the cave and then butchered. Because this is such a large amount of food to consume before spoilage, it is possible these Neanderthals were curing (food preservation), curing and preserving it before winter set in. At 160,000 years old, it is the oldest potential evidence of food storage. The great quantities of meat and fat which could have been gathered in general from typical prey items (namely mammoths) could also indicate food storage capability. With shellfish, Neanderthals needed to eat, cook, or in some manner preserve them soon after collection, as shellfish spoils very quickly. At Cave of Los Aviones, Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the remains of edible, algae eater, algae eating shellfish associated with the alga ''Jania rubens'' could indicate that, like some modern hunter gatherer societies, harvested shellfish were held in water-soaked algae to keep them alive and fresh until consumption.

Competition from large Last Glacial Period, Ice Age predators was rather high. Panthera spelaea, Cave lions likely targeted horses, large deer and wild cattle; and Panthera pardus spelaea, leopards primarily reindeer and roe deer; which heavily overlapped with Neanderthal diet. To defend a kill against such ferocious predators, Neanderthals may have engaged in a group display of yelling, arm waving, or stone throwing; or quickly gathered meat and abandoned the kill. However, at Grotte de Spy, Belgium, the remains of wolves, cave lions, and cave bears—which were all major predators of the time—indicate Neanderthals hunted their competitors to some extent.

Neanderthals and

Competition from large Last Glacial Period, Ice Age predators was rather high. Panthera spelaea, Cave lions likely targeted horses, large deer and wild cattle; and Panthera pardus spelaea, leopards primarily reindeer and roe deer; which heavily overlapped with Neanderthal diet. To defend a kill against such ferocious predators, Neanderthals may have engaged in a group display of yelling, arm waving, or stone throwing; or quickly gathered meat and abandoned the kill. However, at Grotte de Spy, Belgium, the remains of wolves, cave lions, and cave bears—which were all major predators of the time—indicate Neanderthals hunted their competitors to some extent.

Neanderthals and

Neanderthals collected uniquely shaped objects and are suggested to have modified them into pendants, such as a fossil ''Aspa marginata'' sea snail shell possibly painted red from Grotta di Fumane, Italy, transported over to the site about 47,500 years ago; 3 shells, dated to about 120–115 thousand years ago, perforated through the umbo (bivalve), umbo belonging to a Acanthocardia tuberculata, rough cockle, a ''Glycymeris insubrica'', and a ''Spondylus gaederopus'' from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the former two associated with red and yellow pigments, and the latter a red-to-black mix of hematite and pyrite; and a Pecten maximus, king scallop shell with traces of an orange mix of goethite and hematite from Cueva Antón, Spain. The discoverers of the latter two claim that pigment was applied to the exterior to make it match the naturally vibrant inside colouration. Excavated from 1949 to 1963 from the French Grotte du Renne, Châtelperronian beads made from animal teeth, shells, and ivory were found associated with Neanderthal bones, but the dating is uncertain and Châtelperronian artefacts may actually have been crafted by modern humans and simply redeposited with Neanderthal remains.

Neanderthals collected uniquely shaped objects and are suggested to have modified them into pendants, such as a fossil ''Aspa marginata'' sea snail shell possibly painted red from Grotta di Fumane, Italy, transported over to the site about 47,500 years ago; 3 shells, dated to about 120–115 thousand years ago, perforated through the umbo (bivalve), umbo belonging to a Acanthocardia tuberculata, rough cockle, a ''Glycymeris insubrica'', and a ''Spondylus gaederopus'' from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the former two associated with red and yellow pigments, and the latter a red-to-black mix of hematite and pyrite; and a Pecten maximus, king scallop shell with traces of an orange mix of goethite and hematite from Cueva Antón, Spain. The discoverers of the latter two claim that pigment was applied to the exterior to make it match the naturally vibrant inside colouration. Excavated from 1949 to 1963 from the French Grotte du Renne, Châtelperronian beads made from animal teeth, shells, and ivory were found associated with Neanderthal bones, but the dating is uncertain and Châtelperronian artefacts may actually have been crafted by modern humans and simply redeposited with Neanderthal remains.

Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Clive Finlayson, Clive and Geraldine Finlayson suggested that Neanderthals used various bird parts as artistic mediums, specifically black feathers. In 2012, the Finlaysons and colleagues examined 1,699 sites across Eurasia, and argued that Raptor (bird), raptors and corvids, species not typically consumed by any human species, were overrepresented and show processing of only the wing bones instead of the fleshier torso, and thus are evidence of feather plucking of specifically the large flight feathers for use as personal adornment. They specifically noted the cinereous vulture, red-billed chough, kestrel, lesser kestrel, alpine chough, rook (bird), rook, jackdaw, and the white tailed eagle in Middle Palaeolithic sites. Other birds claimed to present evidence of modifications by Neanderthals are the golden eagle, rock pigeon, common raven, and the bearded vulture. The earliest claim of bird bone jewellery is a number of 130,000 year old white tailed eagle talons found in a cache near Krapina, Croatia, speculated, in 2015, to have been a necklace. A similar 39,000-year-old Spanish imperial eagle talon necklace was reported in 2019 at Cova Foradà in Spain, though from the contentious Châtelperronian layer. In 2017, 17 incision-decorated raven bones from the Zaskalnaya VI rock shelter, Ukraine, dated to 43–38 thousand years ago were reported. Because the notches are more-or-less equidistant to each other, they are the first modified bird bones that cannot be explained by simple butchery, and for which the argument of design intent is based on direct evidence.

Discovered in 1975, the so-called Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a mostly flat piece of flint with a bone pushed through a hole on the midsection—dated to 32, 40, or 75 thousand years ago—has been purported to resemble the upper half of a face, with the bone representing eyes. It is contested whether it represents a face, or if it even counts as art. In 1988, American archaeologist Alexander Marshack speculated that a Neanderthal at Grotte de L'Hortus, France, wore a leopard pelt as personal adornment to indicate elevated status in the group based on a recovered leopard skull, phalanges, and tail vertebrae.

Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Clive Finlayson, Clive and Geraldine Finlayson suggested that Neanderthals used various bird parts as artistic mediums, specifically black feathers. In 2012, the Finlaysons and colleagues examined 1,699 sites across Eurasia, and argued that Raptor (bird), raptors and corvids, species not typically consumed by any human species, were overrepresented and show processing of only the wing bones instead of the fleshier torso, and thus are evidence of feather plucking of specifically the large flight feathers for use as personal adornment. They specifically noted the cinereous vulture, red-billed chough, kestrel, lesser kestrel, alpine chough, rook (bird), rook, jackdaw, and the white tailed eagle in Middle Palaeolithic sites. Other birds claimed to present evidence of modifications by Neanderthals are the golden eagle, rock pigeon, common raven, and the bearded vulture. The earliest claim of bird bone jewellery is a number of 130,000 year old white tailed eagle talons found in a cache near Krapina, Croatia, speculated, in 2015, to have been a necklace. A similar 39,000-year-old Spanish imperial eagle talon necklace was reported in 2019 at Cova Foradà in Spain, though from the contentious Châtelperronian layer. In 2017, 17 incision-decorated raven bones from the Zaskalnaya VI rock shelter, Ukraine, dated to 43–38 thousand years ago were reported. Because the notches are more-or-less equidistant to each other, they are the first modified bird bones that cannot be explained by simple butchery, and for which the argument of design intent is based on direct evidence.

Discovered in 1975, the so-called Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a mostly flat piece of flint with a bone pushed through a hole on the midsection—dated to 32, 40, or 75 thousand years ago—has been purported to resemble the upper half of a face, with the bone representing eyes. It is contested whether it represents a face, or if it even counts as art. In 1988, American archaeologist Alexander Marshack speculated that a Neanderthal at Grotte de L'Hortus, France, wore a leopard pelt as personal adornment to indicate elevated status in the group based on a recovered leopard skull, phalanges, and tail vertebrae.

As of 2014, 63 purported engravings have been reported from 27 different European and Middle Eastern Lower-to-Middle Palaeolithic sites, of which 20 are on flint cortexes from 11 sites, 7 are on slabs from 7 sites, and 36 are on pebbles from 13 sites. It is debated whether or not these were made with symbolic intent. In 2012, Gorham's Cave#Scratched floor, deep scratches on the floor of Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, were discovered, dated to older than 39,000 years ago, which the discoverers have interpreted as Neanderthal abstract art. The scratches could have also been produced by a bear. In 2021, an Irish elk phalanx with five engraved offset Chevron (insignia), chevrons stacked above each other was discovered at the entrance to the Einhornhöhle, Einhornhöhle cave in Germany, dating to about 51,000 years ago.

In 2018, some red-painted dots, disks, lines, and hand stencils on the cave walls of the Spanish La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Doña Trinidad were dated to be older than 66,000 years ago, at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe. This would indicate Neanderthal authorship, and similar iconography recorded in other Western European sites—such as Vallée des merveilles, Les Merveilles, France, and Cave of El Castillo, Cueva del Castillo, Spain—could potentially also have Neanderthal origins. However, the dating of these Spanish caves, and thus attribution to Neanderthals, is contested.

Neanderthals are known to have collected a variety of unusual objects—such as crystals or fossils—without any real functional purpose or any indication of damage caused by use. It is unclear if these objects were simply picked up for their aesthetic qualities, or if some symbolic significance was applied to them. These items are mainly quartz crystals, but also other minerals such as cerussite, iron pyrite, calcite, and galena. A few findings feature modifications, such as a mammoth tooth with an incision and a fossil nummulite shell with a cross etched in from Tata, Hungary; a large slab with 18 cupstones hollowed out from a grave in La Ferrassie, France; and a geode from Peștera Cioarei, Romania, coated with red ochre. A number of fossil shells are also known from French Neanderthals sites, such as a rhynchonellid and a ''Taraebratulina'' from Combe Grenal; a belemnite beak from Grottes des Canalettes; a polyp (zoology), polyp from Grotte de l'Hyène; a sea urchin from La Gonterie-Boulouneix; and a rhynchonella, feather star, and belemnite beak from the contentious Châtelperronian layer of Grotte du Renne.

As of 2014, 63 purported engravings have been reported from 27 different European and Middle Eastern Lower-to-Middle Palaeolithic sites, of which 20 are on flint cortexes from 11 sites, 7 are on slabs from 7 sites, and 36 are on pebbles from 13 sites. It is debated whether or not these were made with symbolic intent. In 2012, Gorham's Cave#Scratched floor, deep scratches on the floor of Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, were discovered, dated to older than 39,000 years ago, which the discoverers have interpreted as Neanderthal abstract art. The scratches could have also been produced by a bear. In 2021, an Irish elk phalanx with five engraved offset Chevron (insignia), chevrons stacked above each other was discovered at the entrance to the Einhornhöhle, Einhornhöhle cave in Germany, dating to about 51,000 years ago.

In 2018, some red-painted dots, disks, lines, and hand stencils on the cave walls of the Spanish La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Doña Trinidad were dated to be older than 66,000 years ago, at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe. This would indicate Neanderthal authorship, and similar iconography recorded in other Western European sites—such as Vallée des merveilles, Les Merveilles, France, and Cave of El Castillo, Cueva del Castillo, Spain—could potentially also have Neanderthal origins. However, the dating of these Spanish caves, and thus attribution to Neanderthals, is contested.

Neanderthals are known to have collected a variety of unusual objects—such as crystals or fossils—without any real functional purpose or any indication of damage caused by use. It is unclear if these objects were simply picked up for their aesthetic qualities, or if some symbolic significance was applied to them. These items are mainly quartz crystals, but also other minerals such as cerussite, iron pyrite, calcite, and galena. A few findings feature modifications, such as a mammoth tooth with an incision and a fossil nummulite shell with a cross etched in from Tata, Hungary; a large slab with 18 cupstones hollowed out from a grave in La Ferrassie, France; and a geode from Peștera Cioarei, Romania, coated with red ochre. A number of fossil shells are also known from French Neanderthals sites, such as a rhynchonellid and a ''Taraebratulina'' from Combe Grenal; a belemnite beak from Grottes des Canalettes; a polyp (zoology), polyp from Grotte de l'Hyène; a sea urchin from La Gonterie-Boulouneix; and a rhynchonella, feather star, and belemnite beak from the contentious Châtelperronian layer of Grotte du Renne.

Purported Neanderthal bone flute fragments made of bear long bones were reported from Potok Cave, Potočka zijalka, Slovenia, in the 1920s, and Istállós-kő, Istállós-kői-barlang, Hungary, and Mokriška jama, Slovenia, in 1985; but these are now attributed to modern human activities. The 1995 43 thousand year old Divje Babe Flute from Slovenia has been attributed by some researchers to Neanderthals, and Canadian musicologist Robert Fink said the original flute had either a diatonic scale, diatonic or pentatonic scale, pentatonic musical scale. However, the date also overlaps with modern human immigration into Europe, which means it is also possible it was not manufactured by Neanderthals. In 2015, zoologist Cajus Diedrich argued that it was not a flute at all, and the holes were made by a scavenging hyaena as there is a lack of cut marks stemming from whittling, but in 2018, Slovenian archaeologist Matija Turk and colleagues countered that it is highly unlikely the punctures were made by teeth, and cut marks are not always present on bone flutes.

Purported Neanderthal bone flute fragments made of bear long bones were reported from Potok Cave, Potočka zijalka, Slovenia, in the 1920s, and Istállós-kő, Istállós-kői-barlang, Hungary, and Mokriška jama, Slovenia, in 1985; but these are now attributed to modern human activities. The 1995 43 thousand year old Divje Babe Flute from Slovenia has been attributed by some researchers to Neanderthals, and Canadian musicologist Robert Fink said the original flute had either a diatonic scale, diatonic or pentatonic scale, pentatonic musical scale. However, the date also overlaps with modern human immigration into Europe, which means it is also possible it was not manufactured by Neanderthals. In 2015, zoologist Cajus Diedrich argued that it was not a flute at all, and the holes were made by a scavenging hyaena as there is a lack of cut marks stemming from whittling, but in 2018, Slovenian archaeologist Matija Turk and colleagues countered that it is highly unlikely the punctures were made by teeth, and cut marks are not always present on bone flutes.

There is some debate if Neanderthals had long-ranged weapons. A wound on the neck of an African wild ass from Umm el Tlel, Syria, was likely inflicted by a heavy Levallois-point javelin, and bone trauma consistent with habitual throwing has been reported in Neanderthals. Some spear tips from Abri du Maras, France, may have been too fragile to have been used as thrusting spears, possibly suggesting their use as dart (missile), darts.

There is some debate if Neanderthals had long-ranged weapons. A wound on the neck of an African wild ass from Umm el Tlel, Syria, was likely inflicted by a heavy Levallois-point javelin, and bone trauma consistent with habitual throwing has been reported in Neanderthals. Some spear tips from Abri du Maras, France, may have been too fragile to have been used as thrusting spears, possibly suggesting their use as dart (missile), darts.

The Neanderthals in 10 coastal sites in Italy (namely Grotta del Cavallo and Grotta dei Moscerini) and Kalamakia Cave, Greece, are known to have crafted scrapers using smooth clam shells, and possibly hafted them to a wooden handle. They probably chose this clam species because it has the most durable shell. At Grotta dei Moscerini, about 24% of the shells were gathered alive from the seafloor, meaning these Neanderthals had to wade or dive into shallow waters to collect them. At Grotta di Santa Lucia, Italy, in the Campanian volcanic arc, Neanderthals collected the porous volcanic pumice, which, for contemporary humans, was probably used for polishing points and needles. The pumices are associated with shell tools.

At Abri du Maras, France, twisted fibres and a 3-ply inner-bark-fibre cord fragment associated with Neanderthals show that they produced string and cordage, but it is unclear how widespread this technology was because the materials used to make them (such as animal hair, hide, sinew, or plant fibres) are biodegradable and preserve very poorly. This technology could indicate at least a basic knowledge of weaving and knotting, which would have made possible the production of nets, containers, packaging, baskets, carrying devices, ties, straps, harnesses, clothes, shoes, beds, bedding, mats, flooring, roofing, walls, and snares, and would have been important in hafting, fishing, and seafaring. Dating to 52–41 thousand years ago, the cord fragment is the oldest direct evidence of fibre technology, although 115,000-year-old perforated shell beads from Cueva Antón possibly strung together to make a necklace are the oldest indirect evidence. In 2020, British archaeologist Rebecca Wragg Sykes expressed cautious support for the genuineness of the find, but pointed out that the string would have been so weak that it would have had limited functions. One possibility is as a thread for attaching or stringing small objects.

The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals commonly used animal hide and birch bark, and may have used them to make cooking containers, although this is based largely on circumstantial evidence, because neither fossilizes well. It is possible that the Neanderthals at Kebara Cave, Israel, used the shells of the spur-thighed tortoise as containers.

At the Italian Poggetti Vecchi site, there is evidence that they used fire to process boxwood branches to make digging sticks, a common implement in hunter-gatherer societies.

The Neanderthals in 10 coastal sites in Italy (namely Grotta del Cavallo and Grotta dei Moscerini) and Kalamakia Cave, Greece, are known to have crafted scrapers using smooth clam shells, and possibly hafted them to a wooden handle. They probably chose this clam species because it has the most durable shell. At Grotta dei Moscerini, about 24% of the shells were gathered alive from the seafloor, meaning these Neanderthals had to wade or dive into shallow waters to collect them. At Grotta di Santa Lucia, Italy, in the Campanian volcanic arc, Neanderthals collected the porous volcanic pumice, which, for contemporary humans, was probably used for polishing points and needles. The pumices are associated with shell tools.

At Abri du Maras, France, twisted fibres and a 3-ply inner-bark-fibre cord fragment associated with Neanderthals show that they produced string and cordage, but it is unclear how widespread this technology was because the materials used to make them (such as animal hair, hide, sinew, or plant fibres) are biodegradable and preserve very poorly. This technology could indicate at least a basic knowledge of weaving and knotting, which would have made possible the production of nets, containers, packaging, baskets, carrying devices, ties, straps, harnesses, clothes, shoes, beds, bedding, mats, flooring, roofing, walls, and snares, and would have been important in hafting, fishing, and seafaring. Dating to 52–41 thousand years ago, the cord fragment is the oldest direct evidence of fibre technology, although 115,000-year-old perforated shell beads from Cueva Antón possibly strung together to make a necklace are the oldest indirect evidence. In 2020, British archaeologist Rebecca Wragg Sykes expressed cautious support for the genuineness of the find, but pointed out that the string would have been so weak that it would have had limited functions. One possibility is as a thread for attaching or stringing small objects.

The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals commonly used animal hide and birch bark, and may have used them to make cooking containers, although this is based largely on circumstantial evidence, because neither fossilizes well. It is possible that the Neanderthals at Kebara Cave, Israel, used the shells of the spur-thighed tortoise as containers.

At the Italian Poggetti Vecchi site, there is evidence that they used fire to process boxwood branches to make digging sticks, a common implement in hunter-gatherer societies.

In 1990, two 176,000 year old ring structures, several metres wide, made of broken stalagmite pieces, were discovered in a large chamber more than from the entrance within Bruniquel Cave, Grotte de Bruniquel, France. One ring was with stalagmite pieces averaging in length, and the other with pieces averaging . There were also 4 other piles of stalagmite pieces for a total of or worth of stalagmite pieces. Evidence of the use of fire and burnt bones also suggest human activity. A team of Neanderthals was likely necessary to construct the structure, but the chamber's actual purpose is uncertain. Building complex structures so deep in a cave is unprecedented in the archaeological record, and indicates sophisticated lighting and construction technology, and great familiarity with subterranean environments.

The 44,000 year old Moldova I open-air site, Ukraine, shows evidence of a ring-shaped dwelling made out of mammoth bones meant for long-term habitation by several Neanderthals, which would have taken a long time to build. It appears to have contained hearths, cooking areas, and a flint workshop, and there are traces of woodworking. Upper Palaeolithic modern humans in the Russian plains are thought to have also made housing structures out of mammoth bones.

In 1990, two 176,000 year old ring structures, several metres wide, made of broken stalagmite pieces, were discovered in a large chamber more than from the entrance within Bruniquel Cave, Grotte de Bruniquel, France. One ring was with stalagmite pieces averaging in length, and the other with pieces averaging . There were also 4 other piles of stalagmite pieces for a total of or worth of stalagmite pieces. Evidence of the use of fire and burnt bones also suggest human activity. A team of Neanderthals was likely necessary to construct the structure, but the chamber's actual purpose is uncertain. Building complex structures so deep in a cave is unprecedented in the archaeological record, and indicates sophisticated lighting and construction technology, and great familiarity with subterranean environments.

The 44,000 year old Moldova I open-air site, Ukraine, shows evidence of a ring-shaped dwelling made out of mammoth bones meant for long-term habitation by several Neanderthals, which would have taken a long time to build. It appears to have contained hearths, cooking areas, and a flint workshop, and there are traces of woodworking. Upper Palaeolithic modern humans in the Russian plains are thought to have also made housing structures out of mammoth bones.

Nonetheless, as opposed to the bone sewing-needles and stitching awls assumed to have been in use by contemporary modern humans, the only known Neanderthal tools that could have been used to fashion clothes are hide scraper (archaeology), scrapers, which could have made items similar to blankets or ponchos, and there is no direct evidence they could produce fitted clothes. Indirect evidence of tailoring by Neanderthals includes the ability to manufacture string, which could indicate weaving ability, and a naturally-pointed horse metatarsal bone from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, which was speculated to have been used as an awl, perforating dyed hides, based on the presence of orange pigments. Whatever the case, Neanderthals would have needed to cover up most of their body, and contemporary humans would have covered 80–90%.

Since human/Neanderthal admixture is known to have occurred in the Middle East, and no modern body louse species descends from their Neanderthal counterparts (body lice only inhabit clothed individuals), it is possible Neanderthals (and/or humans) in hotter climates did not wear clothes, or Neanderthal lice were highly specialised.

Nonetheless, as opposed to the bone sewing-needles and stitching awls assumed to have been in use by contemporary modern humans, the only known Neanderthal tools that could have been used to fashion clothes are hide scraper (archaeology), scrapers, which could have made items similar to blankets or ponchos, and there is no direct evidence they could produce fitted clothes. Indirect evidence of tailoring by Neanderthals includes the ability to manufacture string, which could indicate weaving ability, and a naturally-pointed horse metatarsal bone from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, which was speculated to have been used as an awl, perforating dyed hides, based on the presence of orange pigments. Whatever the case, Neanderthals would have needed to cover up most of their body, and contemporary humans would have covered 80–90%.

Since human/Neanderthal admixture is known to have occurred in the Middle East, and no modern body louse species descends from their Neanderthal counterparts (body lice only inhabit clothed individuals), it is possible Neanderthals (and/or humans) in hotter climates did not wear clothes, or Neanderthal lice were highly specialised.

The degree of language complexity is difficult to establish, but given that Neanderthals achieved some technical and cultural complexity, and interbred with humans, it is reasonable to assume they were at least fairly articulate, comparable to modern humans. A somewhat complex language—possibly using syntax—was likely necessary to survive in their harsh environment, with Neanderthals needing to communicate about topics such as locations, hunting and gathering, and tool-making techniques. The FOXP2 gene in modern humans is associated with speech and language development. FOXP2 was present in Neanderthals, but not the gene's modern human variant. Neurologically, Neanderthals had an expanded Broca's area—operating the formulation of sentences, and speech comprehension, but out of a group 48 genes believed to affect the neural substrate of language, 11 had different DNA methylation, methylation patterns between Neanderthals and modern humans. This could indicate a stronger ability in modern humans than in Neanderthals to express language.

In 1971, cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman attempted to reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal tract and concluded that it was similar to that of a newborn and incapable of producing a large range of speech sounds, due to the large size of the mouth and the small size of the pharyngeal cavity (according to his reconstruction), thus no need for a descended larynx to fit the entire tongue inside the mouth. He claimed that they were anatomically unable to produce the sounds /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɔ/, /g/, and /k/ and thus lacked the capacity for articulate speech, though were still able to speak at a level higher than non-human primates. However, the lack of a descended larynx does not necessarily equate to a reduced vowel capacity. The 1983 discovery of a Neanderthal hyoid bone—used in speech production in humans—in Kebara 2 which is almost identical to that of humans suggests Neanderthals were capable of speech. Also, the ancestral Archaeological site of Atapuerca, Sima de los Huesos hominins had humanlike hyoid and ear bones, which could suggest the early evolution of the modern human vocal apparatus. However, the hyoid does not definitively provide insight into vocal tract anatomy. Subsequent studies reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal apparatus as comparable to that of modern humans, with a similar vocal repertoire. In 2015, Lieberman hypothesized that Neanderthals were capable of syntax, syntactical language, although nonetheless incapable of mastering any human dialect.

It is debated if Behavioral modernity, behavioural modernity is a recent and uniquely modern human innovation, or if Neanderthals also possessed it.

The degree of language complexity is difficult to establish, but given that Neanderthals achieved some technical and cultural complexity, and interbred with humans, it is reasonable to assume they were at least fairly articulate, comparable to modern humans. A somewhat complex language—possibly using syntax—was likely necessary to survive in their harsh environment, with Neanderthals needing to communicate about topics such as locations, hunting and gathering, and tool-making techniques. The FOXP2 gene in modern humans is associated with speech and language development. FOXP2 was present in Neanderthals, but not the gene's modern human variant. Neurologically, Neanderthals had an expanded Broca's area—operating the formulation of sentences, and speech comprehension, but out of a group 48 genes believed to affect the neural substrate of language, 11 had different DNA methylation, methylation patterns between Neanderthals and modern humans. This could indicate a stronger ability in modern humans than in Neanderthals to express language.

In 1971, cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman attempted to reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal tract and concluded that it was similar to that of a newborn and incapable of producing a large range of speech sounds, due to the large size of the mouth and the small size of the pharyngeal cavity (according to his reconstruction), thus no need for a descended larynx to fit the entire tongue inside the mouth. He claimed that they were anatomically unable to produce the sounds /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɔ/, /g/, and /k/ and thus lacked the capacity for articulate speech, though were still able to speak at a level higher than non-human primates. However, the lack of a descended larynx does not necessarily equate to a reduced vowel capacity. The 1983 discovery of a Neanderthal hyoid bone—used in speech production in humans—in Kebara 2 which is almost identical to that of humans suggests Neanderthals were capable of speech. Also, the ancestral Archaeological site of Atapuerca, Sima de los Huesos hominins had humanlike hyoid and ear bones, which could suggest the early evolution of the modern human vocal apparatus. However, the hyoid does not definitively provide insight into vocal tract anatomy. Subsequent studies reconstruct the Neanderthal vocal apparatus as comparable to that of modern humans, with a similar vocal repertoire. In 2015, Lieberman hypothesized that Neanderthals were capable of syntax, syntactical language, although nonetheless incapable of mastering any human dialect.

It is debated if Behavioral modernity, behavioural modernity is a recent and uniquely modern human innovation, or if Neanderthals also possessed it.

Although nDNA confirms that Neanderthals and Denisovans are more closely related to each other than they are to modern humans, Neanderthals and modern humans share a more recent maternally-transmitted mtDNA common ancestor, possibly due to interbreeding between Denisovans and some unknown human species. The 400,000-year-old Neanderthal-like humans from Sima de los Huesos in northern Spain, looking at mtDNA, are more closely related to Denisovans than Neanderthals. Several Neanderthal-like fossils in Eurasia from a similar time period are often grouped into ''H. heidelbergensis'', of which some may be relict (biology), relict populations of earlier humans, which could have interbred with Denisovans. This is also used to explain an approximately 124,000 year old German Neanderthal specimen with mtDNA that diverged from other Neanderthals (except for Sima de los Huesos) about 270,000 years ago, while its genomic DNA indicated divergence less than 150,000 years ago.

Sequencing of the genome of a Denisovan from Denisova Cave has shown that 17% of its genome derives from Neanderthals. This Neanderthal DNA more closely resembled that of a 120,000-year-old Neanderthal bone from the same cave than that of Neanderthals from

Although nDNA confirms that Neanderthals and Denisovans are more closely related to each other than they are to modern humans, Neanderthals and modern humans share a more recent maternally-transmitted mtDNA common ancestor, possibly due to interbreeding between Denisovans and some unknown human species. The 400,000-year-old Neanderthal-like humans from Sima de los Huesos in northern Spain, looking at mtDNA, are more closely related to Denisovans than Neanderthals. Several Neanderthal-like fossils in Eurasia from a similar time period are often grouped into ''H. heidelbergensis'', of which some may be relict (biology), relict populations of earlier humans, which could have interbred with Denisovans. This is also used to explain an approximately 124,000 year old German Neanderthal specimen with mtDNA that diverged from other Neanderthals (except for Sima de los Huesos) about 270,000 years ago, while its genomic DNA indicated divergence less than 150,000 years ago.

Sequencing of the genome of a Denisovan from Denisova Cave has shown that 17% of its genome derives from Neanderthals. This Neanderthal DNA more closely resembled that of a 120,000-year-old Neanderthal bone from the same cave than that of Neanderthals from

Whatever the cause of their extinction, Neanderthals were replaced by modern humans, indicated by near full replacement of Middle Palaeolithic Mousterian stone technology with modern human Upper Palaeolithic Aurignacian stone technology across Europe (the Middle-to-Upper Palaeolithic Transition) from 41 to 39 thousand years ago. However, it is postulated that Iberian Neanderthals persisted until about 35,000 years ago indicated by the date range of transitional lithic assemblages—Châtelperronian, Uluzzian, Protoaurignacian, and Early Aurignacian. The latter two are attributed to modern humans, but the former two have unconfirmed authorship, potentially products of Neanderthal/modern human cohabitation and cultural transmission. Further, the appearance of the Aurignacian south of the Ebro River has been dated to roughly 37,500 years ago, which has prompted the "Ebro Frontier" hypothesis which states that the river presented a geographic barrier preventing modern human immigration, and thus prolonging Neanderthal persistence. However, the dating of the Iberian Transition is debated, with a contested timing of 43–40.8 thousand years ago at Cueva Bajondillo, Spain. The Châtelperronian appears in northeastern Iberia about 42.5–41.6 thousand years ago.

Some Neanderthals in Gibraltar were dated to much later than this—such as Zafarraya (30,000 years ago) and Gorham's Cave (28,000 years ago)—which may be inaccurate as they were based on ambiguous artefacts instead of direct dating. A claim of Neanderthals surviving in a polar refuge in the Ural Mountains is loosely supported by Mousterian stone tools dating to 34–31 thousand years ago from the northern Siberian Byzovaya site at a time when modern humans may not yet have colonised the northern reaches of Europe; however, modern human remains are known from the nearby Mamontovaya Kurya site dating to 40,000 years ago. Indirect dating of Neanderthals remains from Mezmaiskaya Cave reported a date of about 30,000 years ago, but direct dating instead yielded 39.7±1.1 thousand years ago, more in line with trends exhibited in the rest of Europe.

Whatever the cause of their extinction, Neanderthals were replaced by modern humans, indicated by near full replacement of Middle Palaeolithic Mousterian stone technology with modern human Upper Palaeolithic Aurignacian stone technology across Europe (the Middle-to-Upper Palaeolithic Transition) from 41 to 39 thousand years ago. However, it is postulated that Iberian Neanderthals persisted until about 35,000 years ago indicated by the date range of transitional lithic assemblages—Châtelperronian, Uluzzian, Protoaurignacian, and Early Aurignacian. The latter two are attributed to modern humans, but the former two have unconfirmed authorship, potentially products of Neanderthal/modern human cohabitation and cultural transmission. Further, the appearance of the Aurignacian south of the Ebro River has been dated to roughly 37,500 years ago, which has prompted the "Ebro Frontier" hypothesis which states that the river presented a geographic barrier preventing modern human immigration, and thus prolonging Neanderthal persistence. However, the dating of the Iberian Transition is debated, with a contested timing of 43–40.8 thousand years ago at Cueva Bajondillo, Spain. The Châtelperronian appears in northeastern Iberia about 42.5–41.6 thousand years ago.

Some Neanderthals in Gibraltar were dated to much later than this—such as Zafarraya (30,000 years ago) and Gorham's Cave (28,000 years ago)—which may be inaccurate as they were based on ambiguous artefacts instead of direct dating. A claim of Neanderthals surviving in a polar refuge in the Ural Mountains is loosely supported by Mousterian stone tools dating to 34–31 thousand years ago from the northern Siberian Byzovaya site at a time when modern humans may not yet have colonised the northern reaches of Europe; however, modern human remains are known from the nearby Mamontovaya Kurya site dating to 40,000 years ago. Indirect dating of Neanderthals remains from Mezmaiskaya Cave reported a date of about 30,000 years ago, but direct dating instead yielded 39.7±1.1 thousand years ago, more in line with trends exhibited in the rest of Europe.

The earliest indication of Upper Palaeolithic modern human immigration into Europe is the Balkan Bohunician industry beginning 48,000 years ago, likely deriving from the Levantine Emiran industry, and the earliest bones in Europe date to roughly 45–43 thousand years ago in Bulgaria, Italy, and Britain. This wave of modern humans replaced Neanderthals. However, Neanderthals and ''H. sapiens'' have a much longer contact history. DNA evidence indicates ''H. sapiens'' contact with Neanderthals and admixture as early as 120–100 thousand years ago. A 2019 reanalysis of 210,000 year old skull fragments from the Greek Apidima Cave assumed to have belonged to a Neanderthal concluded that they belonged to a modern human, and a Neanderthal skull dating to 170,000 years ago from the cave indicates ''H. sapiens'' were replaced by Neanderthals until returning about 40,000 years ago. This identification was refuted by a 2020 study. Archaeological evidence suggests that Neanderthals displaced modern humans in the Near East around 100,000 years ago until about 60–50 thousand years ago.

The earliest indication of Upper Palaeolithic modern human immigration into Europe is the Balkan Bohunician industry beginning 48,000 years ago, likely deriving from the Levantine Emiran industry, and the earliest bones in Europe date to roughly 45–43 thousand years ago in Bulgaria, Italy, and Britain. This wave of modern humans replaced Neanderthals. However, Neanderthals and ''H. sapiens'' have a much longer contact history. DNA evidence indicates ''H. sapiens'' contact with Neanderthals and admixture as early as 120–100 thousand years ago. A 2019 reanalysis of 210,000 year old skull fragments from the Greek Apidima Cave assumed to have belonged to a Neanderthal concluded that they belonged to a modern human, and a Neanderthal skull dating to 170,000 years ago from the cave indicates ''H. sapiens'' were replaced by Neanderthals until returning about 40,000 years ago. This identification was refuted by a 2020 study. Archaeological evidence suggests that Neanderthals displaced modern humans in the Near East around 100,000 years ago until about 60–50 thousand years ago.

It has also been proposed that climate change was the primary driver, as their low population left them vulnerable to any environmental change, with even a small drop in survival or fertility rates possibly quickly leading to their extinction. However, Neanderthals and their ancestors had survived through several glacial periods over their hundreds of thousands of years of European habitation. It is also proposed that around 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthal populations may have already been dwindling from other factors, the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption in Italy could have led to their final demise, as it produced 2–4 °C cooling for a year and acid rain for several more years.

It has also been proposed that climate change was the primary driver, as their low population left them vulnerable to any environmental change, with even a small drop in survival or fertility rates possibly quickly leading to their extinction. However, Neanderthals and their ancestors had survived through several glacial periods over their hundreds of thousands of years of European habitation. It is also proposed that around 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthal populations may have already been dwindling from other factors, the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption in Italy could have led to their final demise, as it produced 2–4 °C cooling for a year and acid rain for several more years.

Neanderthals have been portrayed in popular culture including appearances in literature, visual media, and comedy. The "

Neanderthals have been portrayed in popular culture including appearances in literature, visual media, and comedy. The "

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016). * : Includes Neanderthal mtDNA sequences

GenBank records for ''H. s. neanderthalensis''

maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) {{Authority control Neanderthals, Fossil taxa described in 1864 Stone Age Europe Stone Age Asia

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

or subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

of archaic humans

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

who lived in Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

until about 40,000 years ago. While the "causes of Neanderthal disappearance about 40,000 years ago remain highly contested," demographic factors such as small population size, inbreeding and genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

, are considered probable factors. Other scholars have proposed competitive replacement, assimilation into the modern human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the ...

(bred into extinction), great climatic change

''Climatic Change'' is a biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media covering cross-disciplinary work on all aspects of climate change and variability. It was established in 1978 and the editors-in-chief ...

, disease, or a combination of these factors.

It is unclear when the line of Neanderthals split from that of modern humans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

; studies have produced various intervals ranging from 315,000 to more than 800,000 years ago. The date of divergence of Neanderthals from their ancestor '' H. heidelbergensis'' is also unclear. The oldest potential Neanderthal bones date to 430,000 years ago, but the classification remains uncertain. Neanderthals are known from numerous fossils, especially from after 130,000 years ago. The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

, Neanderthal 1

Feldhofer 1 or Neanderthal 1 is the scientific name of the 40,000-year-old type specimen fossil of the species ''Homo neanderthalensis'', found in August 1856 in a German cave, the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in the Neandertal valley, east of D� ...

, was found in 1856 in the Neander Valley

The Neandertal (, also , ; sometimes called "the Neander Valley" in English) is a small valley of the river Düssel in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located about east of Düsseldorf, the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia. ...

in present-day Germany. For much of the early 20th century, European researchers depicted Neanderthals as primitive, unintelligent, and brutish. Although knowledge and perception of them has markedly changed since then in the scientific community, the image of the unevolved caveman

The caveman is a stock character representative of primitive humans in the Paleolithic. The popularization of the type dates to the early 20th century, when Neanderthals were influentially described as "simian" or " ape-like" by Marcellin Bo ...

archetype

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ...

remains prevalent in popular culture.

Neanderthal technology was quite sophisticated. It includes the Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

stone-tool industry and ability to create fire and build cave hearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by at least a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a lo ...

s, make the adhesive birch bark tar

Birch tar or birch pitch is a substance (liquid when heated) derived from the dry distillation of the bark of the birch tree.

Compounds

It is composed of phenols such as guaiacol, cresol, xylenol, and creosol.

Ancient and modern uses

Birc ...

, craft at least simple clothes similar to blankets and ponchos, weave, go seafaring through the Mediterranean, and make use of medicinal plants

Medicinal plants, also called medicinal herbs, have been discovered and used in traditional medicine practices since prehistoric times. Plants synthesize hundreds of chemical compounds for various functions, including defense and protection ag ...

, as well as treat severe injuries, store food, and use various cooking techniques such as roasting

Roasting is a cooking method that uses dry heat where hot air covers the food, cooking it evenly on all sides with temperatures of at least from an open flame, oven, or other heat source. Roasting can enhance the flavor through caramelizatio ...

, boiling

Boiling is the rapid vaporization of a liquid, which occurs when a liquid is heated to its boiling point, the temperature at which the vapour pressure of the liquid is equal to the pressure exerted on the liquid by the surrounding atmosphere. Th ...

, and smoking

Smoking is a practice in which a substance is burned and the resulting smoke is typically breathed in to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream. Most commonly, the substance used is the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, which have b ...

. Neanderthals made use of a wide array of food, mainly hoofed mammals, but also other megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common thresho ...

, plants, small mammals, birds, and aquatic and marine resources. Although they were probably apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

s, they still competed with cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word "cave" and the scientific name ...

s, cave lions, cave hyaena

The cave hyena (''Crocuta crocuta spelaea''), also known as the Ice Age spotted hyena, was a paleosubspecies of spotted hyena which ranged from the Iberian Peninsula to eastern Siberia. It is one of the best known mammals of the Ice Age and is w ...

s, and other large predators. A number of examples of symbolic thought and Palaeolithic art have been inconclusively attributed to Neanderthals, namely possible ornaments made from bird claws and feathers or shells, collections of unusual objects including crystals and fossils, engravings, music production (possibly indicated by the Divje Babe flute

The Divje Babe flute is a cave bear femur pierced by spaced holes that was unearthed in 1995 during systematic archaeological excavations led by the Institute of Archaeology of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, at ...

), and Spanish cave paintings contentiously dated to before 65,000 years ago. Some claims of religious beliefs have been made. Neanderthals were likely capable of speech, possibly articulate, although the complexity of their language is not known.

Compared with modern humans, Neanderthals had a more robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

build and proportionally shorter limbs. Researchers often explain these features as adaptations to conserve heat in a cold climate, but they may also have been adaptations for sprinting in the warmer, forested landscape that Neanderthals often inhabited. Nonetheless, they had cold-specific adaptations, such as specialised body-fat storage and an enlarged nose to warm air (although the nose could have been caused by genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

). Average Neanderthal men stood around and women tall, similar to pre-industrial modern humans. The braincases of Neanderthal men and women averaged about and respectively, which is within the range of the values for modern humans. The Neanderthal skull was more elongated and had smaller parietal lobes and cerebellum, morphological traits used to assign specimens to species.

The total population of Neanderthals remained low, proliferating weakly harmful gene variants, and precluding effective long-distance networks. Despite this, there is evidence of regional cultures and thus of regular communication between communities. They may have frequented caves, and moved between them seasonally. Neanderthals lived in a high-stress environment with high trauma rates, and about 80% died before the age of 40. The 2010 Neanderthal genome project

The Neanderthal genome project is an effort of a group of scientists to sequence the Neanderthal genome, founded in July 2006.

It was initiated by 454 Life Sciences, a biotechnology company based in Branford, Connecticut in the United States and ...

's draft report presented evidence for interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans. It possibly occurred 316–219 thousand years ago, but more likely 100,000 years ago and again 65,000 years ago. Neanderthals also appear to have interbred with Denisovans

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins ) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains and consequently, most of what is know ...

, a different group of archaic humans, in Siberia. Around 1–4% of genomes of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

ns, Australo-Melanesians

Australo-Melanesians (also known as Australasians or the Australomelanesoid, Australoid or Australioid race) is an outdated historical grouping of various people indigenous to Melanesia and Australia. Controversially, groups from Southeast Asia a ...

, Native Americans, and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

ns is of Neanderthal ancestry, while the inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

have only 0.3% of Neanderthal genes, save possible traces from early Sapiens-to-Neanderthal gene flow and/or more recent back-migration of Eurasians to Africa. In all, about 20% of distinctly Neanderthal gene variants survive today. Although many of the gene variants inherited from Neanderthals may have been detrimental and selected out, Neanderthal introgression

Introgression, also known as introgressive hybridization, in genetics is the transfer of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another by the repeated backcrossing of an interspecific hybrid with one of its parent species. Intr ...

appears to have affected the modern human immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

,

and is also implicated in several other biological functions and structures, but a large portion appears to be non-coding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and regula ...

.

Taxonomy

Etymology

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

until the spelling reform of 1901. The spelling ''Neandertal'' for the species is occasionally seen in English, even in scientific publications, but the scientific name, ''H. neanderthalensis'', is always spelled with ''th'' according to the principle of priority

270px, '' valid name.

Priority is a fundamental principle of modern botanical nomenclature and zoological nomenclature. Essentially, it is the principle of recognising the first valid application of a name to a plant or animal. There are two a ...

. The vernacular name of the species in German is always ''Neandertaler'' ("inhabitant of the Neander Valley"), whereas ''Neandertal'' always refers to the valley. The valley itself was named after the late 17th century German theologian and hymn writer Joachim Neander, who often visited the area. His name in turn means ‘new man’, being a learned Graecization of the German surname ''Neumann''.

''Neanderthal'' can be pronounced using the (as in ) or the standard English pronunciation of ''th'' with the fricative / θ/ (as ).

Neanderthal 1

Feldhofer 1 or Neanderthal 1 is the scientific name of the 40,000-year-old type specimen fossil of the species ''Homo neanderthalensis'', found in August 1856 in a German cave, the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in the Neandertal valley, east of D� ...

, the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

, was known as the "Neanderthal cranium" or "Neanderthal skull" in anthropological literature, and the individual reconstructed on the basis of the skull was occasionally called "the Neanderthal man". The binomial name ''Homo neanderthalensis''—extending the name "Neanderthal man" from the individual specimen to the entire species, and formally recognising it as distinct from humans—was first proposed by Irish geologist William King William King may refer to:

Arts

* Willie King (1943–2009), American blues guitarist and singer

*William King (author) (born 1959), British science fiction author and game designer, also known as Bill King

*William King (artist) (1925–2015), Am ...

in a paper read to the 33rd British Science Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

in 1863. However, in 1864, he recommended that Neanderthals and modern humans be classified in different genera as he compared the Neanderthal braincase to that of a chimpanzee and argued that they were "incapable of moral and theistic

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred t ...

] conceptions".

Research history

The first Neanderthal remains—Engis 2

Engis 2 refers to part of an assemblage, discovered in 1829 by Dutch physician and naturalist Philippe-Charles Schmerling in the lower of the Schmerling Caves. The pieces that make up Engis 2 are a partially preserved calvaria (cranium) and ass ...

(a skull)—were discovered in 1829 by Dutch naturalist Philippe-Charles Schmerling

Philippe-Charles or Philip Carel Schmerling (2 March 1791 Delft – 7 November 1836, Liège) was a Dutch/ Belgian prehistorian, pioneer in paleontology, and geologist. He is often considered the founder of paleontology.

In 1829 he discovered ...

in the Grottes d'Engis, Belgium, but he thought it was a fossil modern human skull. In 1848, Gibraltar 1

Gibraltar 1 is the specimen name of a Neanderthal skull, also known as the Gibraltar Skull found at Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar and presented to the Gibraltar Scientific Society by its secretary, Lieutenant Edmund Henry Réné Flint on 3 March 1 ...

from Forbes' Quarry

Forbes' Quarry is located on the northern face of the Rock of Gibraltar within the Upper Rock Nature Reserve in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. The area was quarried during the 19th century to supply stone for reinforcing the fortr ...

was presented to the Gibraltar Scientific Society by their Secretary Lieutenant Edmund Henry Réné Flint, but was also thought to be a modern human skull. In 1856, local schoolteacher Johann Carl Fuhlrott

Prof. Dr. Johann Carl Fuhlrott (31 December 1803, Leinefelde, Germany – 17 October 1877, Wuppertal) was an early German paleoanthropologist. He is famous for recognizing the significance of the bones of Neanderthal 1, a Neanderthal specimen di ...

recognised bones from Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in Neander Valley—Neanderthal 1 (the holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

)—as distinct from modern humans, and gave them to German anthropologist Hermann Schaaffhausen