History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

was published by senior students in 1844

Describing the earlier venture as having been "starved out", No. 1 of a second ''North Carolina University Magazine'

." Because of lack of students and funding, the university was forced to close from 1870 until 1875.

The

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States ...

is a coeducation

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

al public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

research university located in Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Chapel Hill is a town in Orange, Durham and Chatham counties in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Its population was 61,960 in the 2020 census, making Chapel Hill the 17th-largest municipality in the state. Chapel Hill, Durham, and the state ca ...

, United States. It is one of three schools to claim the title of the oldest public university in the United States

The title of oldest public university in the United States is claimed by three universities: the University of Georgia, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the College of William and Mary. Each has a distinct basis for the claim: N ...

. The first public institution of higher education in North Carolina, the school opened on February 12, 1795.

Until the 1970s, the university was simply known as the University of North Carolina. After the other state universities were combined into a single public university system, called the University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the multi-campus public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the NC School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referred to as the UNC Sy ...

, the original institution was given the new name of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States ...

.

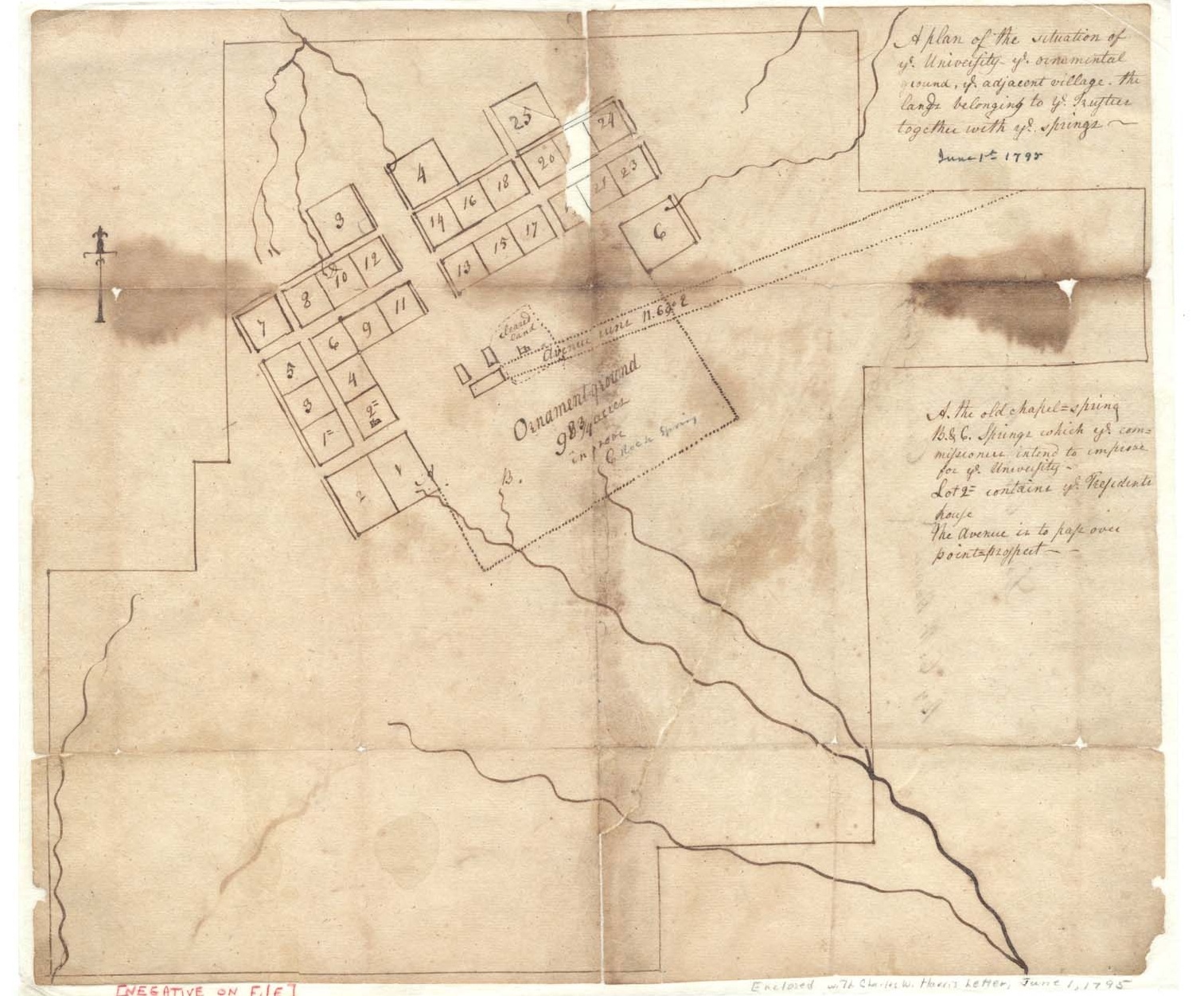

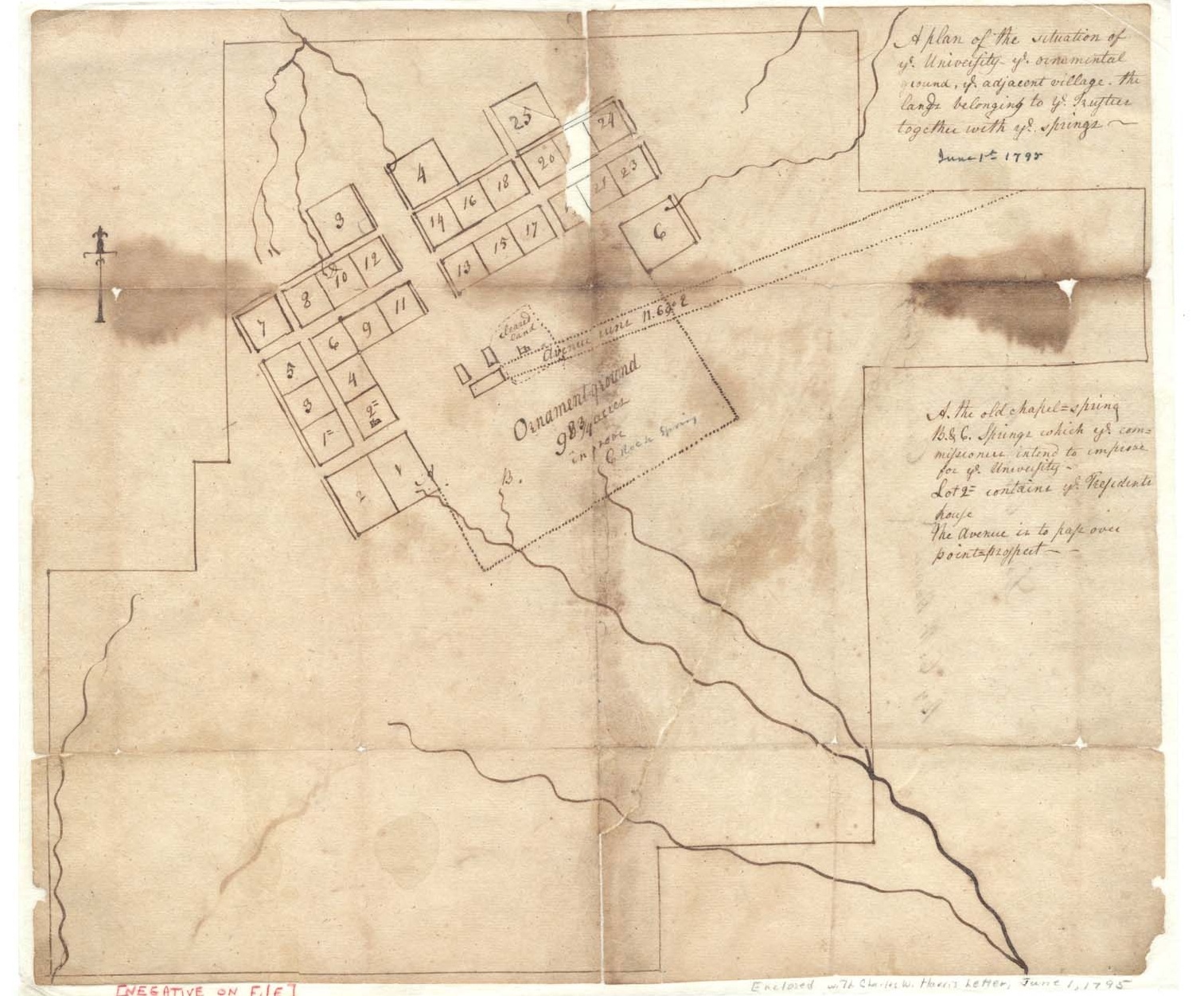

Beginnings: Late 18th century

After the first constitution of the state of North Carolina was adopted in 1776 after the United States declared its independence from theKingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

, work began to establish the independent state of North Carolina. Article 41 of North Carolina Constitution set forth to establish affordable schools and universities for the instruction of the young people in the state. Samuel Eusebius McCorkle made the first attempt to implement article 41. (He is remembered in the name McCorkle Place, on the UNC-CH campus.) In November 1784 he introduced a bill in the North Carolina General Assembly

The North Carolina General Assembly is the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of the Government of North Carolina, State government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the North Carolina Senate, Senate and the North Ca ...

to establish a state university. The bill was rejected due to financial restraints and political turmoil.

Five years later, chartered by the North Carolina General Assembly

The North Carolina General Assembly is the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of the Government of North Carolina, State government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the North Carolina Senate, Senate and the North Ca ...

on December 11, 1789, and beginning instruction in 1795, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States ...

(then named simply the University of North Carolina) is the oldest public university in the nation, as measured by start of instruction as a public institution. The university was the first land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate—land or its use privileges—made by a government or other authority as an incentive, means of enabling works, or as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service. Grants ...

school in North Carolina; however, shortly after they were stripped of their title for using funds in an improper manner. The College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III a ...

, chartered in 1693, and the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

, chartered in 1785, are both older as measured by date of charter. However, William & Mary was originally a private institution, and did not become a public university until 1906. Georgia has always been a public institution, but did not start classes until 1801. A political leader in revolutionary America, William Richardson Davie

William Richardson Davie (June 20, 1756 – November 29, 1820) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States, military officer during the Revolutionary War (United States), Revolutionary War, and List of Go ...

, led efforts to build legislative and financial support for the university.

The site of New Hope Chapel was chosen for "the purity of the water, the salubrity of the air and the great healthfulness of the climate", as well as its location at the center of the state, at the intersection of two major roads.

The university opened in a single building, which came to be called Old East

Old EastItalic text'' is a residence hall located at the north part of campus in University of North Carolina at Chapel HillWhen it was built in 1793,by Slave Laborit became the first state university building in the United States. The Wren Buil ...

. Still in use as a residence hall

A dormitory (originated from the Latin word ''dormitorium'', often abbreviated to dorm) is a building primarily providing sleeping and residential quarters for large numbers of people such as boarding school, high school, college or university s ...

, it is the oldest building originally constructed for a public university in the United States. Davie

Davie is a surname and a form of the masculine given name David.

It can refer to:

Surname

* Alan Davie (1920-2014), Scottish painter and musician

* Alexander Edmund Batson Davie (1847-1889), Canadian politician and eighth Premier of British Col ...

, in full Masonic Ceremony as he was the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of North Carolina

The Grand Lodge of Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons of North Carolina, also known as the Grand Lodge of North Carolina, was founded 12 December 1787. Previously, it was the Provincial Grand Lodge of North Carolina, being under jurisdiction of th ...

at the time, laid the cornerstone on October 12, 1793, near an abandoned Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

chapel which led to the naming of the town as Chapel Hill Chapel Hill or Chapelhill may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Chapel Hill (Antarctica) Australia

*Chapel Hill, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

*Chapel Hill, South Australia, in the Mount Barker council area

Canada

* Chapel Hill, Ottawa, a neighbo ...

. The first student, Hinton James, from near Burgaw

Burgaw is a town in, and the county seat of, Pender County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 3,872 at the 2010 census.

Burgaw is part of the Wilmington Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The town most likely derives its nam ...

in what is now Pender County

Pender County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 60,203. Its county seat is Burgaw. Pender County is part of the Wilmington, NC Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The county ...

, arrived on February 12, 1795. While a student, James was among the students who broke off from the Debating Society (later renamed the Dialectic Society

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

) to form the Concord Society (later renamed the Philanthropic Society

Catch22 is a social business, a not for profit business with a social mission which operates in the United Kingdom (England and Wales). Catch22 can trace its roots back 229 years, to the formation of The Philanthropic Society in 1788. Catch22 desi ...

). A dormitory on the UNC campus is named in his honor. It is currently the southernmost on-campus dormitory and houses primarily first-year students.

When the university opened there were 41 students, rising to 100 in the second term, with a faculty of five. Entering students, according to an 1819 publication, were expected to be able to read the Bible in Greek, and to have read Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

's Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Ca ...

(7 books), Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

's ''Bucolics

The ''Eclogues'' (; ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by offer ...

'' and '' Æneid'', and Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

in Latin, the latter in an "editio expurgata".

When it opened the university received no state financial support, as the charter made no provision for it. The school depended on donations of money and land, "but North Carolinians did not give these generously, feeling that the university was too expensive, too difficult to reach from all areas of the state, and that its liberal and skeptical teachings were insufficiently Christian".

Slavery and the birth of the university

"Members of the Board of Trustees were among the largest slave owners in the state." At a Southern university, "slaves made the bricks that went into buildings, they worked the grounds and buildings around the campus. They carried water, serviced the dormitories, worked in the dining halls."Growth and development: Early 19th century

The early 19th century saw a period of much growth and development with the help of the backing of the trustees. Through this growth, the university began to move away from its original purpose, to train leadership for the state, as it added to the curriculum, first starting with the typical classical trend. By 1815, the university started giving equal ground to thenatural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

, and in 1818 the Department of Chemistry was founded. This development continued with the establishment in 1831 of the first astronomical observatory at a state university in the United States.

Considerable information about university life in Chapel Hill in the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

period is provided by George Moses Horton

George Moses Horton (1798–after 1867), was an African-American poet from North Carolina who was enslaved till the Emancipation Proclamation reached North Carolina (1865). Horton is the first African-American author to be published after th ...

, "the black bard of Chapel Hill" and the first North Carolinian to publish a book of literature. He delivered produce to the campus every week, and goaded by the students, he found he could speak in public and write poems; composing them at night, by memory since he could not write, he provided acrostics and similar light verse. The students, "the sons of wealthy planters", paid him 25¢ to 75¢ for these pieces, which they wrote out and sent to their girlfriends.

According to Horton, the students "seemed more interested in sports, gambling, and pleasures of the table than in their studies. They often engaged in boisterous riots and at various times destroyed laboratories, recitation rooms, and blackboards. They attacked faculty with clubs, stones, and pistols; sang ribald songs; violently rang the university bell; stole farmers' produce and animals; and perpetrated assorted vulgar and dangerous pranks." On the university's own posted history, we find that students hoisted pigs into dormitory rooms. "Cheating became a sport for many students, who transformed it into 'a trial of wit between the class and the Professor, and it was considered good fun to win.' They cut holes in classroom floors, put good students under them, and passed questions down by a string—what was called "working the telegraph." "By all accounts, university students, faculty, and servants drank steadily and heavily.... Even on the Sabbath."

Student behavior later reached the attention of the Trustees, who deplored "gross irregularities of conduct by students on the railroad cars, at circuses and other places". The students on one railroad car were "so boisterous" that it was unhitched, since it was the last car, and the train proceeded without them. A thrown "fireball" deliberately started a fire that destroyed the university's bell and belfry.

The first issue of a ''North Carolina University Magazine'', literary in focuswas published by senior students in 1844

Describing the earlier venture as having been "starved out", No. 1 of a second ''North Carolina University Magazine'

The Hedrick affair

During the lead-up to the U.S. presidential election of 1856, an attack was made in the press on an unidentified professor who allegedly supported anti-slavery candidateJohn C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, whose election, the ''Raleigh Standard

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the seat of Wake County in the United States. It is the second-most populous city in North Carolina, after Charlotte. Raleigh is the tenth-most populous city in the Southea ...

'' opined, would inevitably lead to "a separation of the states". "Let our schools and seminaries of learning be scrutlnized; and if black Republicans rémont supportersbe found in them, let them be driven out. ''That man is neither a fit nor a safe instructor of our young men, who even inclines to Fremont and black Republicanism.''"

Following up on this, a lengthy letter to the editor soon appeared; signed only "Alumnus" (a student), the author was identified by university historian Kemp Battle

Kemp Plummer Battle (December 19, 1831 – February 4, 1919) was an American lawyer, railroad president, university president, educator, and historian. He served as North Carolina State Treasurer and as president of the University of North Caroli ...

as Joseph A. Engelhard.

In another lengthy letter, published by the author as a pamphlet after it appeared in the ''Standard,'' Professor Benjamin Hedrick, an honors graduate of the university, said that there was "little doubt" that he was the professor attacked. He quoted Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

as saying that "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free". Citing as his "political teachers", besides Jefferson, fellow Southerners George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

, Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

, as well as Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

and Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

, "I ''cannot'' believe that slavery is preferable to freedom, or that slavery extension is one of the constitutional rights of the South." According to the newspaper when presenting his letter, "We take it for granted that Prof. Hedrick will be promptly removed." He was hung in effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

; faculty disowned him; parents threatened to withdraw their sons; and alumni joined the public in calling for his dismissal. He refused to resign and since "Mr. Hedrick had greatly, if not entirely, destroyed his power to be of further benefit to the University", he was terminated within a week, though his salary was paid through the end of the term. The only faculty member to defend him, French instructor Henri Herrisse, was terminated at the same time. Hounded by a mob, Hedrick left his native state.

Civil War

During theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, the university was among the few in the Confederacy that managed to keep its doors open. Students from other seceding states left, as did many North Carolina students; by 1864, there were only 47 students. "The war ruined the University financially, so that by 1866, faculty salaries could not be paid; the University was $100,000 in debt; its buildings had deteriorated, and its entire endowment, onverted into Confederate money,">Confederate_money.html" ;"title="onverted into Confederate money">onverted into Confederate money,was lost through the insolvency of the Bank of North Carolina (19th century)">Bank of North Carolina

BNC Bank was a bank based in High Point, North Carolina, United States. In 2014 its parent company BNC Bancorp () had $4.05 billion in assets, 38 branches in North Carolina and 13 in South Carolina. Its latest acquisition gave BNC $6.8 billion in ...Later 19th century

After North Carolina's readmission to the Union in 1868, new political leaders came to power. They attempted to change the direction of the university through political appointments, but these were blocked. The university restored its prestige through growth and innovation, continuing to develop scientific programs. For example, it undertook a massive program to support farmers by conducting scientific analyses of fertilizers and their effectiveness in relation to different crops and soil types in North Carolina. It opened a normal school in 1877, which was both the first university summer school and the first normal school linked to a university in the United States. The university reopened its law school in 1877 and established schools of medicine in 1879 and of pharmacy in 1880.Consolidation: Early 20th century

In 1915, the mission of the university was broadened to include research and public service, culminating in theAssociation of American Universities

The Association of American Universities (AAU) is an organization of American research universities devoted to maintaining a strong system of academic research and education. Founded in 1900, it consists of 63 universities in the United States ( ...

admitting UNC as a member in 1922. This change lead to a large number of new professional schools in the coming years, including:

* School of Education (1915)

* School of Commerce, now Kenan-Flagler Business School (1919)

* School of Public Welfare, now the School of Social Work (1920)

* School of Library Science, now the School of Information and Library Science (1931)

* Institute of Government, now the School of Government (1931)

* School of Public Health, now the Gillings School of Global Public Health (1936)

* Division of Health Affairs (1949)

* School of Dentistry (1949)

* School of Journalism, now the School of Media and Journalism (1950)

* School of Nursing (1950)

In 1915, Cora Zeta Corpening became the first woman enrolled into the medical school.

In 1932, UNC became one of the three original campuses of the consolidated University of North Carolina (since 1972 called the University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the multi-campus public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the NC School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referred to as the UNC Sy ...

system). During the process of consolidation, programs were moved among the schools, which prevented competition. For instance, the engineering school moved from UNC to North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State) is a public land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded in 1887 and part of the University of North Carolina system, it is the largest university in the Carolinas. The universit ...

in Raleigh

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the seat of Wake County in the United States. It is the second-most populous city in North Carolina, after Charlotte. Raleigh is the tenth-most populous city in the Southeas ...

in 1938.

In 1963, the consolidated university was made fully coeducational. As a result, the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina was renamed the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG or UNC Greensboro) is a public research university in Greensboro, North Carolina. It is part of the University of North Carolina system. UNCG, like all members of the UNC system, is a stand-al ...

.

''Silent Sam'' incident

On August 20, 2018, student protestors tore down the university's Confederate monument, known as ''Silent Sam

The Confederate Monument, University of North Carolina, commonly known as ''Silent Sam'', is a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier by Canadian sculptor John A. Wilson, which once stood on McCorkle Place of the University of North Carolina ...

''. The pedestal (plinth

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In c ...

) and plaques were removed shortly afterwards on instructions from then-Chancellor Carol Folt

Carol Lynn Folt (born 1951) is an American academic administrator who is the 12th president of the University of Southern California. She is also the first female president in the university’s 142-year history. She assumed her duties on July 1 ...

(who announced her resignation in the same letter). Although there has been much discussion about what to do with the monument, as of December 2020 it remains in storage.

Renaming Carr Hall

In July 2020, the university's Carr Hall, which was named for former pro-white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

, KKK

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

-supporting Confederate veteran Julian Shakespeare Carr

Julian Shakespeare Carr (October 12, 1845 – April 29, 1924) was an American industrialist, philanthropist, and white supremacist. He is the namesake of the town of Carrboro, North Carolina.

Early life

Carr was the son of Chapel Hill merchan ...

, was renamed "Student Affairs Building." Carr had previously served on the university's Board of Trustees.

References

Further reading

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:University Of North Carolina At Chapel Hill, History OfHistory

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

North Carolina at Chapel Hill