History of the University of Michigan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

The history of the

University President

University President  The 1930s saw a major crackdown on the consumption of alcohol and the rowdiness that had characterized student life practically from inception. In February 1931, local police raided five fraternities, finding liquor and arresting 79 students, including the captain of the football team and ''Michigan Daily'' editors. During the

The 1930s saw a major crackdown on the consumption of alcohol and the rowdiness that had characterized student life practically from inception. In February 1931, local police raided five fraternities, finding liquor and arresting 79 students, including the captain of the football team and ''Michigan Daily'' editors. During the  In 1948, Michigan's

In 1948, Michigan's

During the 1960s, numerous UM faculty members served in the administrations of presidents

During the 1960s, numerous UM faculty members served in the administrations of presidents  An enduring legacy of the 1960s was the sharp rise in campus activism. The campus tumult of the 1960s was to some extent foreshadowed during

An enduring legacy of the 1960s was the sharp rise in campus activism. The campus tumult of the 1960s was to some extent foreshadowed during

''

Official History of the University of Michigan websiteLibraries & Archives Directory for University of MichiganThe University of Michigan - Bentley Historical Library

{{University of Michigan

The history of the

The history of the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

(Michigan) began with its establishment on August 26, 1817 as the Catholepistemiad

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

or University of Michigania.

The Catholepistemiad (1817–1821)

Shortly after theTerritory of Michigan

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit ...

was formed in 1805, several of its leading citizens recognized the need for a structured education. As early as 1806, Father Gabriel Richard

Gabriel Richard (pronounced rish-ARD) October 15, 1767 – September 13, 1832, was a French Roman Catholic priest who ministered to the French Catholics in the parish of Sainte Anne de Détroit, as well as Protestants and Native Americans liv ...

, who ran several schools around the town of Detroit, had requested land for a college from the governor and judges appointed by the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

to administer the territory. Governor William Hull

William Hull (June 24, 1753 – November 29, 1825) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the American Revolutionary War and was appointed as Governor of Michigan Territory (1805–13), gaining large land cessions from several Am ...

and Chief Justice Augustus B. Woodward

Augustus Brevoort Woodward (born Elias Brevoort Woodward; November 1774 – June 12, 1827) was the first Chief Justice of the Michigan Territory. In that position, he played a prominent role in the reconstruction of Detroit following a d ...

passed an act in 1809 to establish public school districts, but this early attempt amounted to little. Woodward harbored a dream of classifying all human knowledge (which he termed ''encathol epistemia''), and discussed the subject with his friend and mentor Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

at Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

in 1814.

In 1817, Woodward drafted a territorial act establishing a "Catholepistemiad, or University, of Michigania," organized into thirteen different professorships, or ''didaxiim'', following the classification system he had published the year before in his ''A System of Universal Science''. He invented names for these using a mix of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

so they could be "engrafted, without variation, into every modern language": ''Anthropoglossica'' (Literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

), ''Mathematica'' (Mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

), ''Physiognostica'' ( Natural History), ''Physiosophica'' (Natural Philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

), ''Astronomia'' (Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

), ''Chymia'' (Chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

), ''Iatrica'' (Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

), ''Œconomica'' ( Economical Sciences), ''Ethica'' (Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

), ''Polemitactica'' (Military Science

Military science is the study of military processes, institutions, and behavior, along with the study of warfare, and the theory and application of organized coercive force. It is mainly focused on theory, method, and practice of producing mil ...

), ''Diëgetica'' ( Historical Sciences), ''Ennœica'' (Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

Sciences), and ''Catholepistemia'' (Universal Science).

The ''Didactor'' (professor) of Catholepistemia was to be the President, and the Didactor of Ennœica the Vice-President. Under the act, the Didactors exercised control over not only the university itself, but education in the territory in general, with the authority to "establish college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offering ...

s, academies

An academy ( Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy ...

, school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compuls ...

s, libraries

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

, museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make these ...

s, atheneums, botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

s, laboratories

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratory services are provided in a variety of settings: physici ...

, and other useful literary and scientific institutions consonant to the laws of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and of Michigan, and provide for and appoint Directors, Visitors, Curators, Librarians, Instructors and Instructrixes among and throughout the various counties, cities, towns, townships, or other geographical divisions of Michigan."

The act was signed into law August 26, 1817, by Woodward, Judge John Griffin John Griffin may refer to:

Lawyers

*John Griffin (judge) (1774/1779 – after 1823), American jurist and member of the Michigan Territorial Supreme Court, 1806–1823

*John Bowes Griffin (1903–1992), British lawyer, Chief Justice of Uganda and f ...

, and acting governor William Woodbridge

William Woodbridge (August 20, 1780October 20, 1861) was a U.S. statesman in the states of Ohio and Michigan and in the Michigan Territory prior to statehood. He served as the second Governor of Michigan and a United States Senator from Mic ...

(Governor Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

was absent on a trip with President Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

). Father Richard was granted six didaxiim (and the Vice-Presidency), and the Rev. John Monteith, who had moved to Detroit a year earlier after graduating from Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of ...

, was granted seven (and the Presidency).

When it came to funding the project, Woodward being a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

himself looked to Zion Lodge No. 1 of Detroit for financial support. On September 15, 1817 Zion Lodge met and subscribed the sum of $250 in aid of the university, payable in the sum of $50 per year. Of the total amount subscribed to start the university two-thirds came from Zion Lodge and its members.

The cornerstone of the university's first building, near the corner of Bates St. and Congress St. in Detroit, was laid on September 24, 1817, and within a year both a primary school

A primary school (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and South Africa), junior school (in Australia), elementary school or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary e ...

and a classical academy were functioning within it.

Five days after the laying of the cornerstone, the Treaty of Fort Meigs

The Treaty of Fort Meigs, also called the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids, formally titled, "Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., 1817", was the most significant Indian treaty by the United States in Ohio since the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. It resulte ...

was signed between the United States and various Native American tribes. Among its provisions was the ceding of of land by the Chippewa, Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, and Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

tribes to the "college at Detroit" for either use or sale, and an equal amount to St. Anne's Church in Detroit, where Father Richard was rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

. No college had officially been created yet, so the next month Monteith and Richard decreed the creation of the "First College of Michigania" at Detroit. Despite this decree, no college was organized, and instruction remained limited to the existing primary school and academy.

The land granted to the college and the church was of two parts, one consisting of three section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sign ...

s near Macon, Michigan and one consisting of three sections to be selected later, with the college and church each having one-half interest in each section. These latter sections were not selected until 1821, and the university received legal title to them in 1824. In 1826, the university swapped its interest in the land at Macon for the church's interest in the others. Though evidence is scant, one historian believes that the land was later sold and the proceeds used in the running of the operation in Detroit.

The University of Michigan was sued in 1971 by descendants of the tribes who claimed that the land grant should have been held in trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

, with the proceeds used to provide for their education. The court ruled in favor of the university, saying the lands were given as an outright gift (due in part to the tribes' affection for Father Richard), and the Michigan Court of Appeals

The Michigan Court of Appeals is the intermediate-level appellate court of the state of Michigan. It was created by the Michigan Constitution of 1963, and commenced operations in 1965. Its opinions are reported both in an official publication of ...

upheld the ruling in 1981.

Name change (1821–1837)

The unwieldy name of the Catholepistemiad and its constituent departments made it a target of ridicule. Governor Cass referred to it as the "Cathole-what's its name" and thought it a "pedantic and uncouth name," while Justice James V. Campbell said it was "neither Greek, Latin, nor English, ut merelya piece of language gone mad." On April 30, 1821, Governor Cass and Judges Griffin andJames Witherell

James Witherell (June 16, 1759 – January 9, 1838) was an American politician. He served as a United States representative from Vermont and as a Judge of the Supreme Court for the Territory of Michigan.

Biography

Witherell was born in Mansfi ...

passed a new act that changed the name of the institution to the University of Michigan and put control in the hands of a Board of Trustees

A board of directors (commonly referred simply as the board) is an executive committee that jointly supervises the activities of an organization, which can be either a for-profit or a nonprofit organization such as a business, nonprofit organiz ...

consisting of 20 members plus the governor, with few other changes to its structure. Rev. Monteith, his office of President abolished, was appointed to the Board of Trustees, but left that summer to accept a professorship at Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a private liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. It was founded as Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and was chartered as Hamilton College in 1812 in honor of inaugural trustee Alexander Hamilton, following ...

. Father Richard was also appointed to the board and remained on it until his death in 1832.

The Trustees continued to oversee operation of the primary school and academy in Detroit and Grand Blanc, at one point reaching an enrollment of 200, but did not establish any additional schools, so the university continued to be one in name only. By 1827, neither school was operating, and the building in Detroit was leased to private teachers. Except as a legal entity, the University of Michigan had essentially ceased to exist.

19th century

Founding

In preparation for statehood, Michigan held a constitutional convention in 1835, although actual statehood was withheld by Congress until 1837, after the resolution of the so-called "Toledo War

The Toledo War (1835–36), also known as the Michigan–Ohio War or the Ohio–Michigan War, was an almost bloodless boundary dispute between the U.S. state of Ohio and the adjoining territory of Michigan over what is now known as the Toledo S ...

" with Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. Sarah Austin's English translation of Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin (; 28 November 179214 January 1867) was a French philosopher. He was the founder of "eclecticism", a briefly influential school of French philosophy that combined elements of German idealism and Scottish Common Sense Realism. As ...

's ''Report on the State of Public Instruction in Prussia'' had just gained widespread attention, and thanks to its influence on two men, John Davis Pierce

John Davis Pierce (February 18, 1797 – April 5, 1882) was a Congregationalist minister, public schools advocate, and Michigan legislator. He was Michigan's first superintendent of public schools, a position new to the United States, where he ...

and Isaac Edwin Crary, the Michigan Constitution

The Constitution of the State of Michigan is the governing document of the U.S. state of Michigan. It describes the structure and function of the state's government.

There have been four constitutions approved by the people of Michigan. The fi ...

of 1835 was the first state constitution in the country to embrace the Prussian model of education, in which a complete system of primary schools, secondary schools, and a university are all administered by the state and supported with tax dollars. The constitution created the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, and Governor Stevens T. Mason appointed Pierce to the post.

The Organic Act of March 18, 1837, created the University of Michigan, governed by a Board of Regents

In the United States, a board often governs institutions of higher education, including private universities, state universities, and community colleges. In each US state, such boards may govern either the state university system, individual col ...

consisting of 12 members appointed by the Governor with the consent of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, along with the Governor himself, the Lieutenant Governor, the Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court

The Michigan Supreme Court is the highest court in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is Michigan's court of last resort and consists of seven justices. The Court is located in the Michigan Hall of Justice at 925 Ottawa Street in Lansing, the state ...

, and the Chancellor of the state. It also created the office of Chancellor of the University, who was to be appointed by the Regents and serve as ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

President of the Board. In practice, however, the Regents never appointed a Chancellor, instead leaving administrative duties up to a rotating roster of professors, and the Governor chaired the board himself.

A group of businessmen called the Ann Arbor Land Company had set land aside in the village of Ann Arbor, trying to win a bid for a new state capital. When that did not happen, they offered it for sale to the state for use by the university. A second act passed two days after the Organic Act called for the University to be established in Ann Arbor, and directed the Regents to secure a site. The Board of Regents held its first meeting in Ann Arbor on June 5, 1837. At this meeting they chose 40 acres on the farm of Henry Rumsey as the new site for the university.

The first classes were held in 1841; six freshmen and a sophomore were taught by two professors. Eleven men graduated in the first commencement ceremony in 1845.

A new state constitution was adopted in 1850, with two significant changes related to the university. The office of Regent was changed from an appointed one to an elected one, and the office of President of the University of Michigan

The president of the University of Michigan is a constitutional officer who serves as the principal executive officer of the University of Michigan. The president is chosen by the Board of Regents of the University of Michigan, as provided for ...

was created, with the Regents directed to select one. In 1852, they chose Henry Philip Tappan

Henry Philip Tappan (April 18, 1805 – November 15, 1881) was an American philosopher, educator and academic administrator. He is officially considered the first president of the University of Michigan.The University of Michigan was establi ...

as the university's first president.

Early Expansion

Tappan modeled UM's curriculum on the broad range of subjects taught at German universities (the so-called "research model"), rather than the classical models (the so-called "recitation model"). The German, or Humboldtian model, was conceived byWilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (, also , ; ; 22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a Prussian philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin, which was named after ...

and based on Friedrich Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional P ...

’s liberal ideas pertaining to the importance of freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving on ...

, seminar

A seminar is a form of academic instruction, either at an academic institution or offered by a commercial or professional organization. It has the function of bringing together small groups for recurring meetings, focusing each time on some parti ...

s, and laboratories

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratory services are provided in a variety of settings: physici ...

in universities. To that end, Tappan enlarged the library, and supported the development and establishment of laboratories, an art gallery, and the Detroit Observatory. However, Tappan was dismissed in 1863 over conflicts with the Board of Regents concerning matters of policy and personality.

The Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

was founded in 1848, and graduated 90 physicians in 1852. UM opened the first university-owned hospital in the U.S. in 1869. The first student newspaper, ''The Peninsular Phoenix and Gazetteer'', was founded in 1857, which was followed by the biweekly ''University Chronicle'' in 1867 and ''The Michigan Daily

''The Michigan Daily'' is the weekly student newspaper of the University of Michigan. Its first edition was published on September 29, 1890. The newspaper is financially and editorially independent of the University's administration and other stu ...

'' in 1890.

By 1865 to 1866, the university's enrollment increased to 1,205 students, with many of the new enrollees veterans of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. In the July 1866 issue of ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'', Harvard University Professor F.H. Hedge depicted UM as the model public institution of higher education for the growing nation. UM began to draw students from across the United States and abroad, and its student body included African Americans. More than 520 of the students enrolled in 1867 were studying at the Medical School. Also in 1867, maize and blue were voted class colors; the Board of Regents made them the official colors of the UM in 1912.

The university's first known African American student, Samuel Codes Watson, was admitted as a medical student in 1853; the first female student, Madelon Louisa Stockwell (lit. 1872) of Kalamazoo, Michigan

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in the southwest region of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the county seat of Kalamazoo County. At the 2010 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 74,262. Kalamazoo is the major city of the Kalamazoo-Portage Metropolit ...

, was admitted in 1870, and the first known African American woman admitted was Mary Henrietta Graham

Mary Henrietta Graham (1857 or 1858 – January 2, 1890) was the first African-American woman to be admitted to the University of Michigan, as well as the first biracial person to graduate from it.

Early life

Graham was born in Windsor, Ontario ...

, in 1876 (lit. 1880). By 1882, UM's alumnae included the president of Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a private women's liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henry and Pauline Durant as a female seminary, it is a member of the original Seven Sisters Colleges, an unofficial g ...

, Alice Elvira Freeman Palmer

Alice Freeman Palmer (born Alice Elvira Freeman; February 21, 1855 – December 6, 1902) was an American educator. As Alice Freeman, she was president of Wellesley College from 1881 to 1887, when she left to marry the Harvard professor George H ...

. The growing student body also led to unruliness. In 1872, Ann Arbor hosted 49 saloons, and the spectacle of student intoxication and public donnybrooks concerned school administrators and state politicians. ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' published an article in July 1887 that noted the school's "broad and liberal spirit" and the wide-ranging freedoms of its students.

In 1871, James B. Angell, president of the University of Vermont

The University of Vermont (UVM), officially the University of Vermont and State Agricultural College, is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Burlington, Vermont. It was founded in 1791 and is amon ...

, was appointed president of UM, a position that he held until 1909. Angell aggressively expanded the university's curriculum to include and expand professional studies in dentistry, architecture, engineering, government, and medicine. In 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

appointed Angell a special minister to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

to negotiate the immigration of Chinese laborers. Angell's publicity efforts abroad eventually prompted a large influx of foreign students to the university. UM also began to attract renowned faculty, including pragmatist philosopher John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

, who taught at the university from 1884 to 1894, and Thomas M. Cooley, who left the university when he was appointed the first chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminat ...

by President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

.

Michigan in the 20th century

University President

University President Marion LeRoy Burton

Marion LeRoy Burton (August 30, 1874 – February 18, 1925) was the second president of Smith College, serving from 1910 to 1917. He left Smith to become president of the University of Minnesota from 1917 to 1920. In 1920 he became president o ...

's tenure, which started in 1920, saw the advent of major field research initiatives in Africa, South America, the South Pacific, and the Middle East. Burton raised admissions standards and sought to heighten the academic rigors of the university's courses, while taming the often-rowdy social lives of his students. Burton later made the nominating speech at the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal of the Repu ...

for incumbent president Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

in 1924. Shortly after attaining his place in the national spotlight, Burton died of a heart attack in February 1925. The memorial bell tower

The Main Campus is the primary campus of North Carolina State University, located in Raleigh, North Carolina, US, inside the Beltline. Notable features of Main Campus include the Bell Tower and D. H. Hill Library. The campus is known for its di ...

that bears his name remains a prominent campus landmark. Burton was succeeded by Clarence Cook Little

Clarence Cook Little (October 6, 1888 – December 22, 1971) was an American genetics, cancer, and tobacco researcher and academic administrator, as well as a eugenicist.

Early life

C. C. Little was born in Brookline, Massachusetts and atte ...

, a highly divisive figure who, among other things, offended Roman Catholics with his vocal endorsements of contraception.

The 1930s saw a major crackdown on the consumption of alcohol and the rowdiness that had characterized student life practically from inception. In February 1931, local police raided five fraternities, finding liquor and arresting 79 students, including the captain of the football team and ''Michigan Daily'' editors. During the

The 1930s saw a major crackdown on the consumption of alcohol and the rowdiness that had characterized student life practically from inception. In February 1931, local police raided five fraternities, finding liquor and arresting 79 students, including the captain of the football team and ''Michigan Daily'' editors. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, ritual and widespread freshman hazing all but ceased. Long known as a "dressy campus," student attire became less formal. Fraternities and sororities became less prominent in student life, as their finances and memberships went into steep decline.

UM's position as a prominent research university gained momentum in 1920 with a formal reorganization of the College of Engineering

Engineering education is the activity of teaching knowledge and principles to the professional practice of engineering. It includes an initial education ( bachelor's and/or master's degree), and any advanced education and specializations tha ...

and the formation of an advisory committee of 100 industrialists to guide academic research initiatives. In addition, 1933 saw the completion of the new Law Quadrangle, a gift from alumnus William W. Cook. The quadrangle quickly became a campus landmark, known for its integration of residence and legal scholarship.

In 1943, Michigan was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

which offered students a path to a Navy commission.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the university grew into a true research powerhouse, undertaking major initiatives on behalf of the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

and contributing to weapons development with breakthroughs including the VT fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, ...

, depth bombs, the PT boat, and radar jammers. By 1950, university enrollment had reached 21,000, of whom 7,700 were veterans supported by the G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

. In the same year, the university purchased of land north of the Huron River that would later become North Campus.

In 1948, Michigan's

In 1948, Michigan's Institute for Social Research

The Institute for Social Research (german: Institut für Sozialforschung, IfS) is a research organization for sociology and continental philosophy, best known as the institutional home of the Frankfurt School and critical theory. Currently a part ...

(ISR) was established by Rensis Likert

Rensis Likert ( ; August5, 1903September3, 1981) was an American organizational and social psychologist known for developing the Likert scale, a psychometrically sound scale based on responses to multiple questions. The scale has become a method ...

. Harlan H. Hatcher, an administrator at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

and professor of English, was appointed university president in 1951. Hatcher fostered early construction in the school's nascent North Campus, and created an Honors College for 5% of entering freshmen. As the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

and the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

took shape, UM became a principal recipient of government research grants, and its researchers were on the vanguard of exploring peacetime uses for atomic power. During Hatcher's administration, the ISR, with its ambitious ongoing effort focused on research and applications of social science, received its own building. In a 1966 report by the American Council on Education

The American Council on Education (ACE) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) U.S. higher education association established in 1918. ACE's members are the leaders of approximately 1,700 accredited, degree-granting colleges and universities and higher education ...

, the university was rated first or second in the nation in graduate teaching of all 28 disciplines surveyed. In 1971, the central library on campus was named the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library.

The beginning of Hatcher's presidency saw the university in the national spotlight over the first-ever "panty raid

A panty raid was an American 1950s and early 1960s college prank in which large groups of male students attempted to invade the living quarters of female students and steal their panties (undergarments) as the trophies of a successful raid. The ...

" in 1952, an event cheered on by hundreds of students and chronicled by the national press, including ''Life Magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

''. Hatcher's legacy is marked, however, by a much more serious controversy: his suspension of three faculty members—Chandler Davis, Clement Markert, and Mark Nicholson—under pressure from Rep. Kit Clardy and his subcommittee of the House Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

. Davis ultimately was sentenced to prison for contempt, a conviction that he appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

.

During the 1960s, numerous UM faculty members served in the administrations of presidents

During the 1960s, numerous UM faculty members served in the administrations of presidents Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

and John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

. During their administrations, 15 alumni served in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

. On October 14, 1960, Kennedy, who once referred to Harvard as "The Michigan of the East," announced his intention to form the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John F. ...

in a speech on the steps of the Michigan Union

The Michigan Union is a student union at the University of Michigan. It is located at the intersection of South State Street and South University Avenue in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The building was built in 1917 and is one of several unions at the U ...

, and by 1966 332 UM alumni were serving in the Corps. In a commencement address at Michigan Stadium

Michigan Stadium, nicknamed "The Big House," is the football stadium for the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is the largest stadium in the United States and the Western Hemisphere, the third largest stadium in the world, and the ...

on May 22, 1964, President Johnson first announced his intentions to pursue his Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the University ...

reforms.

An enduring legacy of the 1960s was the sharp rise in campus activism. The campus tumult of the 1960s was to some extent foreshadowed during

An enduring legacy of the 1960s was the sharp rise in campus activism. The campus tumult of the 1960s was to some extent foreshadowed during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when disputes arose between faculty, administrators, and students over issues including military instruction and teaching of the German language. In the 1930s, student groups had formed to promote socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

, isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entang ...

, and pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

, as well as interest in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. Political dissent, largely mollified by campus consensus during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, returned to UM with a vengeance during the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

and the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

On November 5, 1962, Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

delivered two speeches to capacity crowds in Hill Auditorium and also participated in an intimate student discussion and faculty dinner reception at the Michigan Union. “The American dream is as yet unfulfilled,” he said, in his only known visit to Ann Arbor.

On March 24, 1964, a group of faculty held the nation's first "teach-in

A teach-in is similar to a general educational forum on any complicated issue, usually an issue involving current political affairs. The main difference between a teach-in and a seminar is the refusal to limit the discussion to a specific time fr ...

" to protest American policy in Southeast Asia. 2,500 students attended the event. A series of 1966 sit-ins by Voice, the campus political party of Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s, and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships ...

, prompted the administration to ban sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

s, a move that, in turn, led 1,500 students to conduct a one-hour sit-in in the administration building. In September 1969, a 12,000-student march followed a Michigan football game; on October 15, 1969, 20,000 rallied against the war in Michigan Stadium. Radicals adopted increasingly confrontational tactics, including an episode in which members of the Jesse James Gang, an SDS offshoot, locked themselves in a room with an on-campus military recruiter and refused to release him. Hatcher's successor, Robben Wright Fleming

Robben Wright Fleming (December 18, 1916 – January 11, 2010), also known in his youth as Robben Wheeler Fleming, was an American lawyer, professor, and academic administrator. He was president of the University of Michigan from 1968 to 1979� ...

—an experienced labor negotiator and former chancellor of the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. Universities ty ...

—is credited by university historian Howard Peckham with preventing the campus from experiencing the violent outbreaks seen at other American universities.

Low minority enrollment was also a cause of unrest. In March 1970, the Black Action Movement, an umbrella name for a coalition of student groups, sponsored a campus-wide strike to protest low minority enrollment and to build support for an African American Studies department. The strike included picket lines that prevented entrance to university buildings and was widely observed by students and faculty. Eight days after the strike began, the university granted many of BAM's demands.

Campus activism also changed the character of student social life. By 1973, only 4.7% of the student body participated in fraternities and sororities. The university's student government fell one vote short of approving a marijuana

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and entheogenic purposes and in various tra ...

co-op that was based on the premise of high-quantity purchases and free distribution. Such attitudes persist in the Hash Bash

Hash Bash is an annual event held in Ann Arbor, Michigan, originally held every April 1, but now on the first Saturday of April at noon on the University of Michigan Diag. A collection of speeches, live music, and occasional civil disobedience ...

, a rally and festival calling for the legalization of marijuana use held annually on and near campus.

During the 1970s, severe budget constraints hindered to some extent the university's physical development and academic standing. For the previous 50 years, all major academic surveys had listed Michigan as one of the nation's top five universities, a standing that began to diminish. For instance, the student-faculty ratio at the U-M Law School became the highest of any elite law school in the U.S. Though the undergraduate division is currently ranked in the top 25, the university is acknowledged to have a faculty whose teaching awards, publications, patents and citations generally rank in the top five in the U.S.

The university's financial condition improved under the leadership of President Harold Shapiro, a former economics professor, during the 1980s. The university again saw a surge in funds devoted to research in the social and physical sciences, although campus controversy arose over involvement in the anti-missile Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the "''Star Wars'' program", was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (intercontinental ballistic ...

and investments in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

. A new hospital complex was opened in 1986, including a new University Hospital and the A. Alfred Taubman Health Care Center that centralized outpatient care provided by the Medical School faculty. Also in 1986, UM launched M-CARE, a managed care health plan that provided HMO coverage and other plans to university faculty and staff, retirees, dependents, and to employers in the community.

President James Duderstadt

James Johnson Duderstadt was the President of the University of Michigan from 1988 to 1996.

Duderstadt was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering in 1987 for significant contributions to nuclear science and engineering relating t ...

, whose tenure ran from 1988 to 1995, was a nuclear engineer and former engineering dean who emphasized uses for computer and information technology. Duderstadt facilitated achievements in the campus's physical growth and fundraising efforts. His successor, Lee Bollinger

Lee Carroll Bollinger (born April 30, 1946) is an American lawyer and educator who is serving as the 19th and current president of Columbia University, where he is also the Seth Low Professor of the University and a faculty member of Columbia La ...

, had a relatively brief tenure before departing to lead Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. Two major construction initiatives in the late 1990s were (1) the University of Michigan School of Social Work building constructing a brand new dedicated building on the corner of South and East University. and (2) Tisch Hall addition to Angell Hall, named in honor of a $6M gift from mall developer Preston Robert Tisch

Preston Robert Tisch (April 29, 1926 – November 15, 2005) was an American businessman who was the chairman and—along with his brother Laurence Tisch—was part owner of the Loews Corporation. From 1991 until his death, Tisch owned 50 ...

.

Present day

In the early 2000s, the UM faced declining state funding as a percentage of its funding due to state budget shortfalls. At the same time, UM has attempted to maintain its high academic standing while keeping tuition costs affordable. The university administration also faced labor disputes withlabor union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s, notably with the Lecturers' Employees Organization (LEO) and the Graduate Employees Organization (GEO), the union representing graduate student employees.

In 2003, two lawsuits involving the school's affirmative action admissions policy reached the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

(Grutter v. Bollinger

''Grutter v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 306 (2003), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning affirmative action in student admissions. The Court held that a student admissions process that favors "underrepresented minor ...

and Gratz v. Bollinger). President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

took the unusual step of publicly opposing the policy before the court issued a ruling, though the eventual ruling was mixed. In the first case, the court upheld the Law School

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

admissions policy while in the second, it ruled against the university's undergraduate admissions policy.

The debate still continues, however, because in November 2006 Michigan voters passed proposal 2, banning most affirmative action in university admissions. Under that law race, gender, and national origin can no longer be considered in admissions.University of Michigan Drops Affirmative Action for Now (11 January 2007)''

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

.'.' Retrieved January 12, 2007. UM and other organizations were granted a stay from implementation of the passed proposal soon after that election, and this has allowed time for proponents of affirmative action to decide legal and constitutional options in response to the election results. The university has stated it plans to continue to challenge the ruling; in the meantime, the admissions office states that it will attempt to achieve a diverse student body by looking at other factors such as whether the student attended a disadvantaged school, and the level of education of the student's parents.

In late 2006, with the climate for health plans changing rapidly throughout the region and the U.S., the university made the decision to sell M-CARE to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and its Blue Care Network subsidiary. As part of the sale, a new health care quality organization called Michigan HealthQuarters was founded.

In 2021 music professor Bright Sheng

Bright Sheng ( Chinese: 盛宗亮 pinyin: ''Shèng Zōngliàng''; born December 6, 1955) is a Chinese-born American composer, pianist and conductor. Sheng has earned many honors for his music and compositions, including a MacArthur Fellowship in ...

stepped down from teaching an undergraduate

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, in the United States, an entry-lev ...

musical composition

Musical composition can refer to an original piece or work of music, either vocal or instrumental, the structure of a musical piece or to the process of creating or writing a new piece of music. People who create new compositions are called ...

class, where he says he had intended to show how Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

adapted William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cypru ...

'' into his opera ''Otello

''Otello'' () is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on Shakespeare's play ''Othello''. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887.

Th ...

'', after a controversy over his showing the 1965 British movie ''Othello'', allegedly without giving students any warning that it contained blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

. The controversy took place against a background of sexual misconduct scandals at the university in recent years, both inside

Inside may refer to:

* Insider, a member of any group of people of limited number and generally restricted access

Film

* ''Inside'' (1996 film), an American television film directed by Arthur Penn and starring Eric Stoltz

* ''Inside'' (2002 f ...

and outside the music department.

Campus history

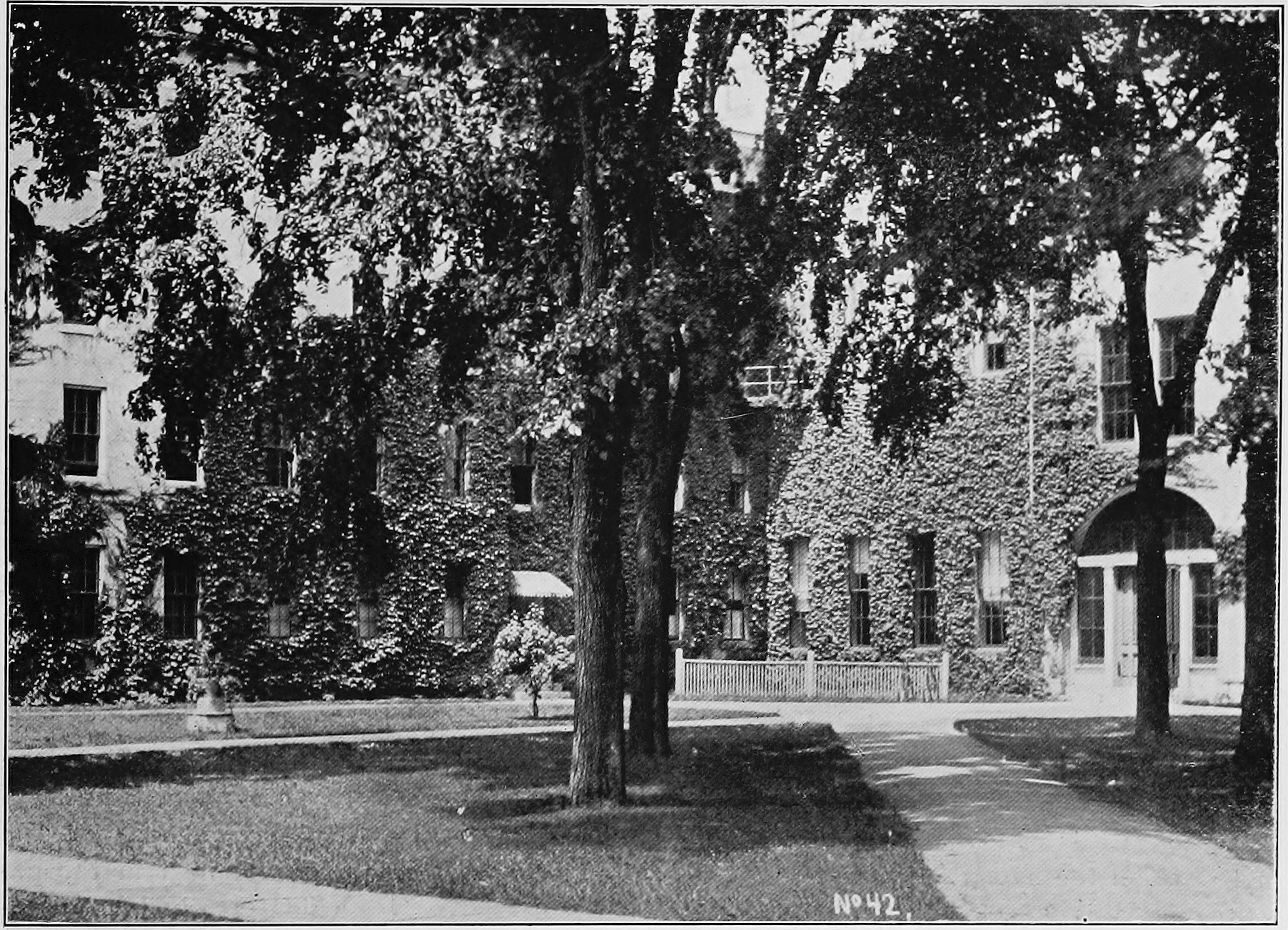

The Ann Arbor campus originally started on of land bounded by State Street on the west, North University Avenue on the north, East University Avenue on the east, and South University Avenue on the south. The first two decades of the 20th century saw a construction boom on campus that included facilities to house the dental and pharmacy programs, a chemistry building, a building for the study of natural sciences, theMartha Cook Building

Martha Cook is a Collegiate Gothic women's residence hall at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. The building houses approximately 140 women pursuing undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University. Women may live in the building th ...

and Helen Newberry residence halls, Hill Auditorium

Hill Auditorium is the largest performance venue on the University of Michigan campus, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The auditorium was named in honor of Arthur Hill (1847-1909), who served as a regent of the university from 1901 to 1909. He bequeathe ...

, and large hospital and library complexes. University President Burton continued the construction boom through the 1920s, including the construction of Michigan Stadium

Michigan Stadium, nicknamed "The Big House," is the football stadium for the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is the largest stadium in the United States and the Western Hemisphere, the third largest stadium in the world, and the ...

. In 1925, The University Hospital (also known as the Main Hospital) replaced the Catherine Street Hospital. Designed by Albert Kahn, the 893-bed hospital was the largest and most modern facility of its kind in the nation, and was used until 1986. Land for North Campus, which would house the College of Engineering, the School of Music, and the A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture & Urban Planning was purchased in 1950.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the university devoted substantial resources to renovating its massive hospital complex and improving the academic facilities on the university's North Campus. At a time when many other universities were choosing to sell their hospitals and clinics, UM created a tighter bond between its Medical School and its Hospitals & Health Centers unit in 1997, forming the University of Michigan Health System

Michigan Medicine (University of Michigan Health System or UMHS before 2017) is the wholly owned academic medical center of the University of Michigan, a public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Michigan Medicine includes the Universi ...

to act as an "umbrella" over those entities and M-CARE, and designating an Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs who reports directly to the President. The result has been a financially strong and synergistic system for health care delivery, research and medical/bioscience education.

Nevertheless, in the past decade roughly $2.5 billion has been budgeted and expended toward such construction, with approximately another $4.8 billion in construction projects in 17 new buildings underway or in planning for the coming decade. Recently, the university has constructed over 1 million square feet (90,000 m²) of academic and laboratory space devoted to the life sciences. In 2005, the university unveiled a development master-plan for the medical campus that is expected to add 3 million square feet (270,000 m²) to the existing 5 million square feet (450,000 m²). Examples of new buildings include the Cardiovascular Center, the Biomedical Science Research Building, the Rachel Upjohn Building and the replacement for C.S. Mott Children's Hospital and Women's Hospital, scheduled to open in 2011.

The Ann Arbor campus is divided into four main areas: the North, Central, Medical, and South Campuses. The physical infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

includes more than 500 major buildings, with a combined area of more than 37.48 million square feet (860 acres or 3.48 km²). The campus also consists of leased space in buildings scattered throughout the city, many occupied by organizations affiliated with the University of Michigan Health System. An East Medical Campus has recently been developed on Plymouth Road, with several university-owned buildings for outpatient care, diagnostics, and outpatient surgery. The university also has an office building called Wolverine Tower in southern Ann Arbor near Briarwood Mall. Another major facility is the Matthaei Botanical Gardens, which is located on the eastern outskirts of Ann Arbor.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

Official History of the University of Michigan website

{{University of Michigan