The foundation of the

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

(german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD) can be traced back to the 1860s, and it has represented the

centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

in German politics for much of the 20th and 21st centuries. From 1891 to 1959, the SPD theoretically espoused

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

.

The SPD has been the ruling party at several points, first under

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

in 1918. The party was outlawed in

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

but returned to government in 1969 with

Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ger ...

. Meanwhile, the

East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

branch of the SPD was merged with the ruling

Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

. In the modern

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

, the SPD's main rival is the

CDU; as of 2022, the SPD is in government in coalition with the

FDP and

the Greens The Greens or Greens may refer to:

Current political parties

*Australian Greens, also known as ''The Greens''

*Greens of Andorra

* Greens of Bosnia and Herzegovina

*Greens of Burkina

* Greens (Greece)

* Greens of Montenegro

*Greens of Serbia

*Gree ...

, with

Olaf Scholz

Olaf Scholz (; born ) is a German politician who has served as the chancellor of Germany since 8 December 2021. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he previously served as Vice Chancellor under Angela Merkel and as Federal Minister ...

from the SPD as Chancellor.

German Reich

German Empire (1863–1918)

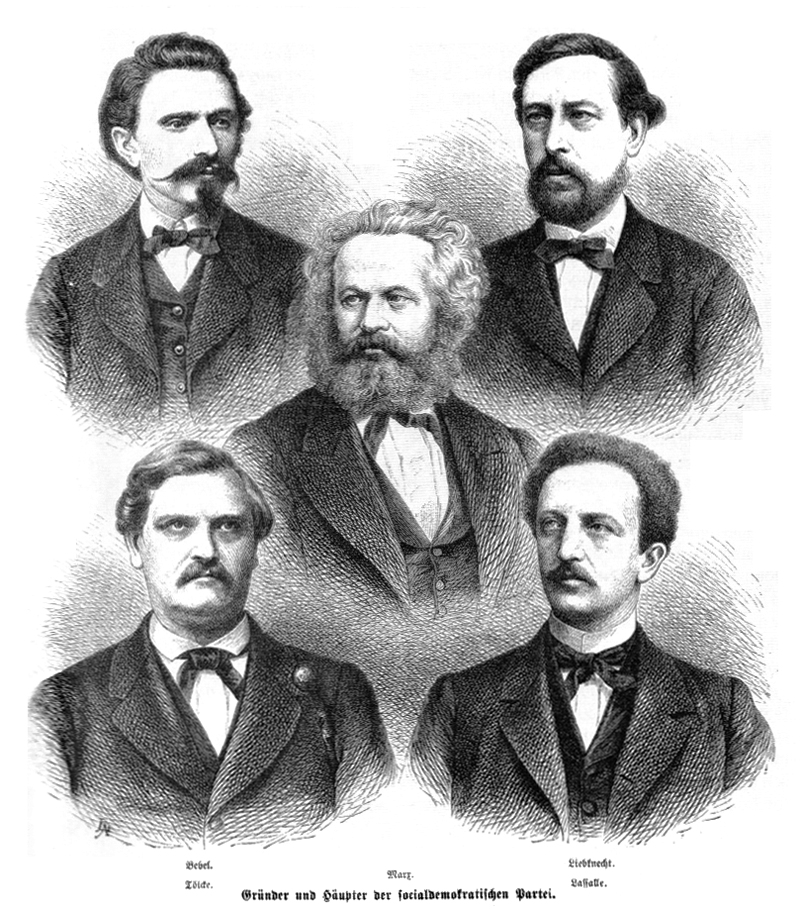

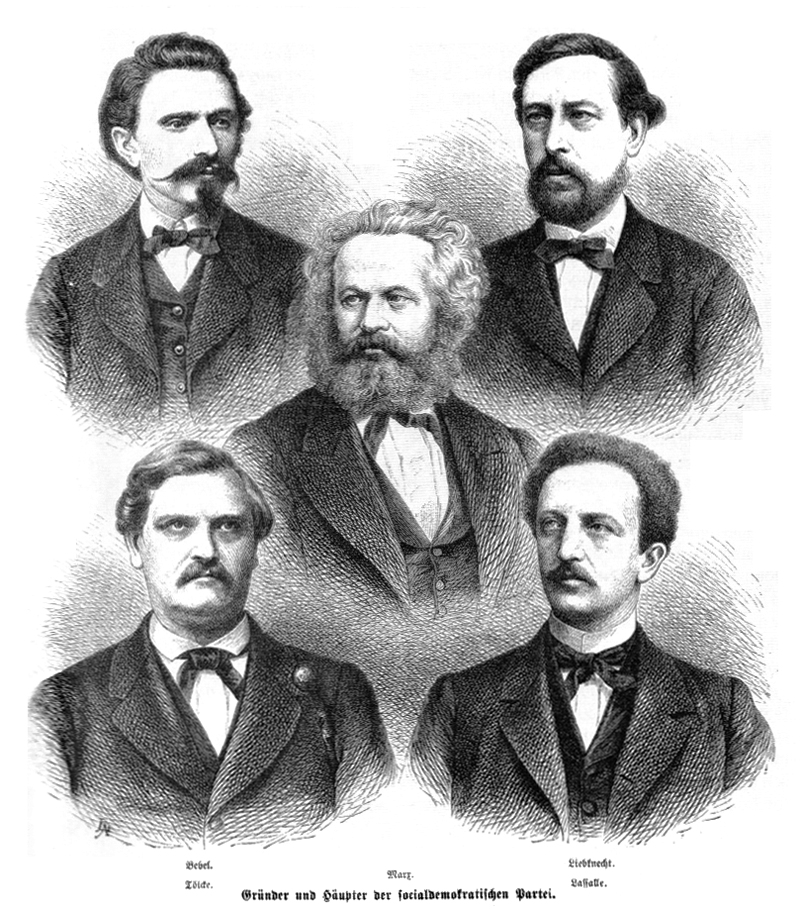

The party was founded on 23 May 1863 by

Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Lassalle (; 11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864) was a Prussian-German jurist, philosopher, socialist and political activist best remembered as the initiator of the social democratic movement in Germany. "Lassalle was the first man in G ...

under the name ''Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein'' (ADAV,

General German Workers' Association

The General German Workers' Association (german: Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV) was a German political party founded on 23 May 1863 in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony by Ferdinand Lassalle. It was the first organized mass working-cla ...

). In 1869,

August Bebel

Ferdinand August Bebel (22 February 1840 – 13 August 1913) was a German socialist politician, writer, and orator. He is best remembered as one of the founders of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) in 1869, which in 1875 mer ...

and

Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist and one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SDAP) was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Founded in Eisenach in 1869, the SDAP ...

), which merged with the ADAV at a conference held in Gotha in 1875, taking the name ''Socialist Workers' Party of Germany'' (SAPD). At this conference, the party developed the

Gotha Program

The Gotha Program was the party platform adopted by the nascent Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) at its initial party congress, held in the town of Gotha in 1875. The program called for universal suffrage, freedom of association, limit ...

, which

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

criticized in his ''

Critique of the Gotha Program

The ''Critique of the Gotha Programme'' (german: Kritik des Gothaer Programms) is a document based on a letter by Karl Marx written in early May 1875 to the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), with whom Marx and Friedrich Engels wer ...

''. Through the

Anti-Socialist Laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

,

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

had the party outlawed for its pro-revolution, anti-monarchy sentiments in 1878; but in 1890 it was legalized again. That year - in its

Halle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

convention - it changed its name to ''Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands'' (SPD), as it is known to this day.

Anti-socialist campaigns were counterproductive. 1878 to 1890 was the SPD's "heroic period". The party's new program drawn up in 1891 at Halle was more radical than 1875's

Gotha program

The Gotha Program was the party platform adopted by the nascent Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) at its initial party congress, held in the town of Gotha in 1875. The program called for universal suffrage, freedom of association, limit ...

. From 1881 to 1890 the party's support increased faster than in any other period. In 1896, the

National Liberals and

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

replaced the democratic vote with a Prussian-style three-tiered suffrage, upper class votes counting the most. They did this to drive out the local SPD which lost its last seat in 1901. However, in the 1903 election, the number of socialist deputies increased from 11 to 22 out of 23.

Because Social Democrats could be elected as list-free candidates while the party was outlawed, SPD continued to be a growing force in the

Reichstag, becoming the strongest party in 1912 (in the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, the parliamentary balance of forces had no influence on the formation of the cabinet). During this period, SPD deputies in the

Reichstag were able to win some improvements in working and living conditions for working-class Germans,

thereby advancing the cause of its policies in a general way and securing material benefits for its supporters.

[The German Social Democratic Party, 1875–1933: From Ghetto To Government by W. L. Guttsman]

In the

Landtag

A Landtag (State Diet) is generally the legislative assembly or parliament of a federated state or other subnational self-governing entity in German-speaking nations. It is usually a unicameral assembly exercising legislative competence in non ...

, the SPD was able to extract some concessions from time to time in areas for which the assembly was responsible, such as education and social policy. In Hesse, the party was successful in demanding that church tax be listed separately in assessments, and it was able to secure improvements in judicial procedure. The SPD also had occasional successes in raising wages and improving the working conditions of municipal labourers.

SPD pressure in the Reichstag in the late nineteenth century supported an expansion in the system of factory inspection, together with a minor reform in military service under which the families of reservists, called up for training or manoeuvres, could receive an allowance. In the 1880s, SPD deputies in Saxony successfully agitated in support of improved safety for miners and better control of mines.

In 1908, the same year the government legalized women's participation in politics,

Luise Zietz became the first woman appointed to the executive committee of the SPD.

Despite the passage of anti-socialist legislation, the SPD continued to grow in strength in the early twentieth century, with a steady rise in membership from 384,327 in 1905/06 to 1,085,905 in 1913/14. SPD was seen as a populist party, and people from every quarter of German society sought help and advice from it. With its counseling service (provided free of charge by the mostly trade union maintained workers’ secretarial offices), the German social democratic movement helped large numbers of Germans to secure their legal rights, primarily in social security. There also existed a dynamic educational movement, with hundreds of courses and individual lectures, theatre performances, libraries, peripatetic teachers, a central school for workers’ education, and a famous Party School, as noted by the historians Susanne Miller and Heinrich Potthoff:

Growth in strength did not initially translate into larger numbers in the Reichstag. The original constituencies had been drawn at the empire's formation in 1871, when Germany was almost two-thirds rural. They were never redrawn to reflect the dramatic growth of Germany's cities in the 1890s. By the turn of the century, the urban-rural ratio was reversed, and almost two-thirds of all Germans lived in cities and towns. Even with this change, the party still managed to become the largest single faction in the Reichstag at the 1912 elections. It would be the largest party in Germany for the next two decades.

In the states of

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

,

Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Württ ...

,

Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are ...

, and

Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

, the SPD was successful in extracting various socio-political and democratic concessions (including the replacement of the class-based electoral systems with universal suffrage) through electoral alliances with bourgeois parties, voting for parliamentary bills and state budgets. In the Reichstag, the SPD resorted to a policy of tactical compromise in order to exert direct influence on legislation. In 1894, the parliamentary SPD voted for a government bill for the first time ever. It reduced the import duty on wheat, which led to a reduction in the price of food. In 1913, the votes of SPD parliamentarians helped to bring in new tax laws affecting the wealthy, which were necessary due to the increase in military spending.

The Social Democrats gave particular attention to carrying out reforms at the local level, founding a tradition of community politics which intensified after 1945. The establishment of local labour exchanges and the introduction of unemployment benefits can be credited in part to the SPD. In 1913, the number of Social Democrats on municipal and district councils approached 13,000. As noted by Heinrich Potthoff and Susanne Miller:

As Sally Waller wrote, the SPD encouraged great loyalty from its members by organising educational courses, choral societies, sports clubs, and libraries. The party also ran welfare clinics, founded libraries, produced newspapers, and organised holidays, rallies, and festivals. As also noted by Weller, they played a role in shaping a number of progressive reforms:

According to historian Richard M. Watt:

Erfurt Program and revisionism (1891–1899)

As a reaction to government prosecution, the

Erfurt Program of 1891 was more radical than the Gotha Program of 1875, demanding

nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

of Germany's major industries. In fact in 1891 the party officially became a Marxist Party to the gratification of aging Engels. However, the party began to move away from

revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

at the turn of the 20th century.

Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl Marx and Friedr ...

authored a series of articles on the ''Problems of Socialism'' between 1896 and 1898, and later a book, ''Die Voraussetzungen des Sozialismus und die Aufgaben der Sozialdemokratie'' ("The Prerequisites for Socialism and the Tasks of Social Democracy"), published in 1899, in which he argued that the winning of reforms under capitalism would be enough to bring about socialism. Radical party activist

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialism, revolutionary socialist, Marxism, Marxist philosopher and anti-war movement, anti-war activist. Succ ...

accused Bernstein of

revisionism and argued against his ideas in her pamphlet

Social Reform or Revolution

''Social Reform or Revolution?'' (german: Sozialreform oder Revolution?) is an 1899 pamphlet by Polish- German Marxist theorist Rosa Luxemburg. Luxemburg argues that trade unions, reformist political parties and the expansion of social democracy� ...

, and Bernstein's program was not adopted by the party.

First World War (1912–1917)

Conservative elites nevertheless became alarmed at SPD growth—especially after it won 35% of the national vote in the

1912 German federal election

Federal elections were held in Germany on 12 January 1912.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p762 Although the Social Democratic Party (SPD) had received the most votes in every election since 1890, ...

. Some elites looked to a foreign war as a solution to Germany's internal problems. SPD policy limited antimilitarism to aggressive wars—Germans saw 1914 as a defensive war. On 25 July 1914, the SPD leadership appealed to its membership to demonstrate for peace and large numbers turned out in orderly demonstrations. The SPD was not revolutionary and many members were nationalistic. When the war began, some conservatives wanted to use force to suppress the SPD, but Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg refused. However, the increasing loyalty of the party establishment towards Emperor and Reich, coupled with its antipathy toward Russia led the party under Bebel's successor

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

to support the war. This was helped by the fact that Germany had waited until after the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

announced mobilization to begin its own mobilization, allowing Germany to claim it was the victim of Russian aggression. The SPD members of the

Reichstag voted 96–14 on 3 August 1914 to support the war. They next voted the money for the war, but resisted demands for an aggressive peace policy that would involve takeover of new territories. Even if socialists felt beleaguered in Germany, they knew they would suffer far more under

Tsarist autocracy; the gains they had made for the working class, politically and materially, now required them to support the nation.

There remained an antiwar element especially in Berlin. They were expelled from the SPD in 1916 and formed the

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) was a short-lived political party in Germany during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The organization was establish ...

. Bernstein left the party during the war, as did

Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels ...

, who had played an important role as the leading Marxist theoretician and editor of the theoretical journal of SPD, “

Die Neue Zeit

''Die Neue Zeit'' (German: "The New Times") was a German socialist theoretical journal of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) that was published from 1883 to 1923. Its headquarters was in Stuttgart, Germany.

History and profile

Founded ...

”. Neither joined the

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

after the war; they both came back to the SPD in the early 1920s, From 1915 on theoretical discussions within the SPD were dominated by a group of former

anti-revisionist

Anti-revisionism is a position within Marxism–Leninism which emerged in the 1950s in opposition to the reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Where Khrushchev pursued an interpretation that differed from his predecessor Joseph Stalin, ...

Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, who tried to legitimize the support of the First World War by the German SPD group in the Reichstag with Marxist arguments. Instead of the class struggle they proclaimed the struggle of peoples. The group was led by

Heinrich Cunow Heinrich Cunow (11 April 1862, in Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Schwerin – 20 August 1936) was a German Social Democratic Party politician and a Marxist theorist.

Cunow was originally against the First World War in 1914 but he changed his viewpoint. ...

,

Paul Lensch

Paul Lensch (31 March 1873 in Potsdam, Province of Brandenburg – 18 November 1926 in Berlin) was a war journalist, editor, author of several books and politician in the SPD. From 1912, Lensch was a member of the German Reichstag for the SPD, ...

and

Konrad Haenisch

Konrad Haenisch (13 March 1876 – 28 April 1925) was a German Social Democratic Party politician and part of "the radical Marxist Left" of German politics. He was a friend and follower (''Parvulus'' in his own words) of Alexander Parvus.

Life

...

(“Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch-Gruppe”) and was close to the Russian-German revolutionary and social scientist

Alexander Parvus

Alexander Lvovich Parvus, born Israel Lazarevich Gelfand (8 September 1867 – 12 December 1924) and sometimes called Helphand in the literature on the Russian Revolution, was a Marxist theoretician, publicist, and controversial activist in the ...

, who gave a public forum to the group with his journal “Die Glocke”. From the teachings of

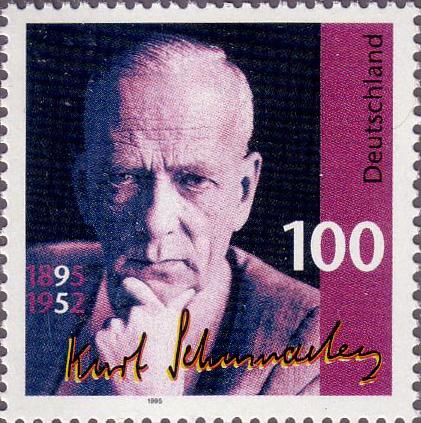

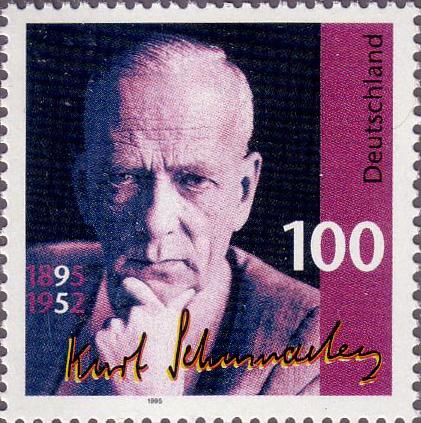

Kurt Schumacher

Curt Ernst Carl Schumacher, better known as Kurt Schumacher (13 October 1895 – 20 August 1952), was a German politician who became chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Germany from 1946 and the first Leader of the Opposition in the Wes ...

and Professor

Johann Plenge

Johann Max Emanuel Plenge (7 June 1874 – 11 September 1963) was a German sociologist. He was professor of political economy at the University of Münster.

In his book ''1789 and 1914,'' Plenge contrasted the 'Ideas of 1789' (liberty) and the ...

, there is a link to the current centrist “

Seeheimer Kreis

The Seeheimer Kreis (; English: "Seeheim Circle") is an official internal grouping in the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The group describes itself as "undogmatic and pragmatic" and generally takes moderately liberal economic positio ...

” within the SPD founded by

Annemarie Renger

Annemarie Renger (née Wildung), (7 October 1919 in Leipzig – 3 March 2008 in Remagen-Oberwinter), was a German politician for the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

From 1972 until 1976 she served as the 5th President of the Bundestag. ...

, Schumacher's former secretary.

Those against the war were expelled from the SPD in January 1917 (including

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialism, revolutionary socialist, Marxism, Marxist philosopher and anti-war movement, anti-war activist. Succ ...

,

Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag fro ...

and

Hugo Haase) - the expellees went on to found the

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) was a short-lived political party in Germany during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The organization was establish ...

, in which the

Spartacist League

The Spartacus League (German: ''Spartakusbund'') was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the "International Group" by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and othe ...

was influential.

German Revolution (1918–1919)

In the

1918 revolution, Ebert controversially sided with the

Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

against the

Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolutio ...

, while the

Reichstag elected him as

head of the new government.

A revolutionary government met for the first time in November 1918. Known as the

Council of People's Commissioners, it consisted of three Majority Social Democrats (

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

,

Philipp Scheidemann, and

Otto Landsberg

Otto Landsberg (4 December 1869 – 9 December 1957) was a German jurist, politician and diplomat. He was a member of the revolutionary Council of the People's Deputies that took power during the German Revolution of 1918–19 and then served as ...

) and three United Social Democrats (

Emil Barth,

Wilhelm Dittman, and

Hugo Haase). The new government faced a social crisis in the German Reich following the end of the First World War, with Germany threatened by hunger and chaos. There was, for the most part, an orderly return of soldiers back into civilian life, while the threat of starvation was combated.

Wage levels were raised, universal proportional representation for all parliaments was introduced, and a series of regulations on

unemployment benefits

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a comp ...

, job-creation and protection measures,

health insurance

Health insurance or medical insurance (also known as medical aid in South Africa) is a type of insurance that covers the whole or a part of the risk of a person incurring medical expenses. As with other types of insurance, risk is shared among m ...

,

and

pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

saw the institution of important political and social reforms. In February 1918, workers made an agreement with employers which secured them total freedom of association, the legal guarantee of an

eight-hour workday, and the extension of wage agreements to all branches of trade and industry. The People's Commissioners made these changes legally binding.

In addition, the SPD-steered provisional government introduced binding state arbitration of labor conflicts, created worker's councils in large industrial firms, and opened the path to the unionization of rural labourers. In December 1918, a decree was passed providing relief for the unemployed. This provided that communities were to be responsible for unemployment relief (without fixing an amount) and established that the Reich would contribute 50% and the respective German state 33% of the outlay. That same month, the government declared that labour exchanges were to be further developed with the financial assistance of the Reich. Responsibility for job placement was first transferred from the Demobilization Office to the Minister of Labour and then to the National Employment Exchange Office, which came into being in January 1920.

[''The Evolution of Social Insurance 1881–1981'': Studies of Germany, France, Great Britain, Austria, and Switzerland edited by Peter A. Kohler and Hans F. Zacher in collaboration with ]Martin Partington

Thomas Martin Partington, (born 5 March 1944) is a British retired legal scholar and barrister. He is Emeritus professor of Law at the University of Bristol.'PARTINGTON, Prof. (Thomas) Martin', ''Who's Who 2017'', A & C Black, an imprint of Bloo ...

Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Subsequently, the Social Democratic Party and the newly founded

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

(KPD), which consisted mostly of former members of the SPD, became bitter rivals, not least because of the legacy of the

German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

. Under

Defense Minister of Germany

The Federal Minister of Defence (german: Bundesminister der Verteidigung) is the head of the Federal Ministry of Defence and a member of the Federal Cabinet.

According to Article 65a of the German Constitution (german: Grundgesetz), the Fede ...

Gustav Noske, the party aided in putting down the Communist and left wing

Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolutio ...

throughout Germany in early 1919 with the use of the

Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

, a morally questionable decision that has remained the source of much controversy amongst historians to this day. While the KPD remained in staunch opposition to the newly established parliamentary system, the SPD became a part of the so-called

Weimar Coalition, one of the pillars of the struggling republic, leading several of the short-lived interwar

cabinets. The threat of the Communists put the SPD in a difficult position. The party had a choice between becoming more radical (which could weaken the Communists but lose its base among the

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

) or stay moderate, which would damage its base among the working class. Splinter groups formed: In 1928, a small group calling itself

Neu Beginnen

Neu Beginnen (English: " obegin anew") was an anti-fascist opposition group formed in 1929 by left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party. After the Nazis seized power in 1933, the members of the small group discussed what the future of Ger ...

, in the autumn of 1931, the

Socialist Workers' Party of Germany. The

Iron Front

The Iron Front (german: Eiserne Front) was a German paramilitary organization in the Weimar Republic which consisted of social democrats, trade unionists, and liberals. Its main goal was to defend liberal democracy against totalitarian ide ...

, founded in December 1931, was not a splinter party but a nonpartisan association led mostly by the SPD.

Welfare state (1918–1926)

Under Weimar, the SPD was able put its ideas of social justice into practice by influencing a number of progressive social changes while both in and out of government. The SPD re-introduced and overhauled the Bismarckian welfare state, providing protection for the disadvantaged, the unemployed, the aged, and the young. The “Decree on Collective Agreements, Workers’ and Employees’ Committees, and the Settlement of Labour Disputes” of December 1918 boosted the legal effectiveness of collective bargaining contracts,

while a number of measures were carried out to assist veterans, including the Decree on Social Provision for Disabled Veterans and Surviving Dependents of February 1919 and the Compensation Law for Re-enlisted Men and Officers of September 1919. The War Victims’ Benefits Law of May 1920 introduced a more generous war-disability system than had existed in the past.

This new piece of legislation took into account all grievances voiced during the war and, for the first time in social legislation in Germany, considered child maintenance in calculating widows’ pensions.

In 1919, the federal government launched a campaign to recolonize parts of the German interior including in Silesia,

and new provisions for maternity were introduced.

In February 1920, an industrial relations law was passed, giving workers in industry legally guaranteed representation, together with the right to

co-determination

In corporate governance, codetermination (also "copartnership" or "worker participation") is a practice where workers of an enterprise have the right to vote for representatives on the board of directors in a company. It also refers to staff having ...

in cases of hiring and firing, holiday arrangements, the fixing of working hours and regulations, and the introduction of new methods of payment. A Socialisation Law was also passed, while the government adopted guidelines on the

workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

s. In addition to workers' councils at national, regional, and factory level, the government made provision for economic councils in which employers and employees would work together on matters affecting the economy as a whole (such as nationalisation) and lend support to the Weimar parliament.

SPD governments also introduced unemployment insurance benefits for all workers (in 1918), trade union recognition and an eight-hour workday, while municipalities that came under SPD control or influence expanded educational and job-training opportunities and set up health clinics. Off the shop floor, Social Democratic workers took advantage of the adult education halls, public libraries, swimming pools, schools, and low-income apartments built by municipalities during the Weimar years, while considerable wage increases won for the majority of workers by the

Free Trade Unions between 1924 and 1928 helped to narrow the gap between unskilled and skilled workers. A number of reforms were also made in education, as characterised by the introduction of the four-year common primary school. Educational opportunities were further widened by the promotion of

adult education

Adult education, distinct from child education, is a practice in which adults engage in systematic and sustained self-educating activities in order to gain new forms of knowledge, skills, attitudes, or values. Merriam, Sharan B. & Brockett, Ral ...

and culture.

The SPD also played an active and exemplary role in the development of local politics in thousands of towns and communities during this period. In 1923, the SPD Minister of Finance,

Rudolf Hilferding, laid much of the groundwork for the stabilization of the German currency.

As noted by Edward R. Dickinson, the

German Revolution of 1918–1919

The German Revolution or November Revolution (german: Novemberrevolution) was a civil conflict in the German Empire at the end of the First World War that resulted in the replacement of the German federal constitutional monarchy with a d ...

and the democratisation of the state and local franchise provided Social Democracy with a greater degree of influence at all levels of government than it had been able to achieve before 1914. As a result of the reform of municipal franchises, socialists gained control of many of the country's major cities. This provided Social Democrats with a considerable degree of influence in social policy, as most welfare programmes (even those programmes mandated by national legislation) were implemented by municipal government. By the Twenties, with the absence of a revolution and the reformist and revision element dominant in the SPD, Social Democrats regarded the expansion of social welfare programmes, and particularly the idea that the citizen had a right to have his or her basic needs met by society at large, as central to the construction of a just and democratic social order. Social Democrats therefore pushed the expansion of social welfare programmes energetically at all levels of government, and SPD municipal administrations were in the forefront of the development of social programmes. As remarked by

Hedwig Wachenheim in 1926, under Social Democratic administration many of the country's larger cities began to become experimental “proletarian cooperatives.”

Protective measures for workers were vastly improved, under the influence or direction of the SPD, and members of the SPD pointed to positive changes that they had sponsored, such as improvements in public health, unemployment insurance, maternity benefits, and the building of municipal housing. During its time in opposition throughout the Twenties, the SPD was able to help push through a series of reforms beneficial to workers, including increased investment in

public housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, de ...

, expanded disability, health, and social insurance programmes, the restoration of an eight-hour workday in large firms, and the implementation of binding arbitration by the Labour Ministry.

In 1926, the Social Democrats were responsible for a law which increased maternity benefit "to cover the cost of midwifery, medical help and all necessary medication and equipment for home births."

In government (1918–1924; 1928–1930)

In the

Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

, (which became an SPD stronghold following the introduction of

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

) an important housing law was passed in 1918 which empowered local authorities to erect small dwellings and buildings of public utility, provide open spaces, and enact planning measures. The law further directed that all districts with more than 10,000 inhabitants had to issue police ordinances regarding housing hygiene. In addition, a reform in education was carried out.

Similar measures were introduced in other areas subjected to the influence of the SPD, with the Reich (also under the influence of the SPD) controlling rents and subsidising the construction of housing.

[Germany In The Twentieth Century by David Childs]

During the Weimar era, the SPD held the chancellorship on two occasions, first from 1918 to 1920, and then again from 1928 to 1930. Through aggressive opposition politics, the SPD (backed by the union revival linked to economic upsurge) was able to effect greater progress in social policy from 1924 to 1928 than during the previous and subsequent periods of the party's participation in government.

In Prussia, the SPD was part of the government from 1918 to 1932, and for all but nine months of that time (April–November 1921 and February–April 1925), a member of the SPD was minister president.

The SPD's last period in office was arguably a failure, due to both its lack of a parliamentary majority (which forced it to make compromises to right-wing parties) and its inability to confront the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. In 1927, the defence ministry had prevailed on the government of

Wilhelm Marx to provide funds in its draft budget of 1928 for the construction of the first of six small battleships allowed for under the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, although the Federal Council (largely for financial reasons) stopped this action. This issue played a major role during the

1928 German federal election

Federal elections were held in Germany on 20 May 1928.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p762 The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) remained the largest party in the Reichstag after winning 1 ...

, with supporters of the proposal arguing that all the possibilities left for German armaments should be fully used, while the SPD and the KPD saw this as a wasteful expenditure, arguing that such money should instead be spent on providing free meals for schoolchildren. The SPD's lack of a parliamentary majority (which prevented it from undertaking any major domestic reform) meant that, in order to hold the coalition together,

Hermann Müller and the other SPD ministers were forced to make concessions on issues such as taxation, unemployment insurance, and the construction of pocket battleships.

Party chairman

Otto Wels demanded that the funds be spent on free school meals as had been promised during the election campaign. However, against the wishes and votes of Wels and the other SPD deputies, the SPD ministers in Müller's cabinet (including Müller himself) voted in favour of the first battleship being built, a decision that arguably destroyed the party's credibility.

Müller's SPD government eventually fell as a result of the catastrophic effects of the Great Depression. Müller's government, an ideologically diverse “Grand Coalition” representing five parties ranging from the left to the right, was unable to develop effective counter-measures to tackle the catastrophic effects of the economic crisis, as characterised by the massive rise in the numbers of registered unemployed. In 1928–29, 2.5 million were estimated to be unemployed, a figure that reached over 3 million by the following winter. A major problem facing Müller's government was a deficit in the Reich budget, which the government spending more than it was receiving. This situation was made worse by the inadequacy of the unemployment scheme which was unable to pay out enough benefits to the rising numbers of unemployed, forcing the government to make contributions to the scheme (which in turn worsened the budget deficit). The coalition was badly divided on this issue, with the SPD wishing to raise the level of contributions to the scheme while safeguarding both those in work and those out of work as much as possible. The right-wing parties, by contrast, wished to reduce unemployment benefits while lightening the tax burden. Unable to garner enough support in the Reichstag to pass laws, Müller turned to President

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

for support, wishing him to grant him the use of the emergency powers under

Article 48

Article 48 of the constitution of the Weimar Republic of Germany (1919–1933) allowed the President, under certain circumstances, to take emergency measures without the prior consent of the '' Reichstag''. This power was understood to include ...

of the

Weimar Constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (german: Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (''Weimarer Verfassung''), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era (1919–1933). The c ...

so that he did not have to rely on support from the Reichstag.

Müller refused to agree to reductions in unemployment benefit which the

Centre Party under

Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

saw as necessary. The government finally collapsed in March 1930 when Müller (lacking support from Hindenburg) resigned, a fall from office that according to the historian

William Smaldone marked “the effective end of parliamentary government under Weimar.”

Collapse (1932–1933)

On 20 July 1932, the SPD-led Prussian government in Berlin, headed by

Otto Braun

Otto Braun (28 January 1872 – 15 December 1955) was a politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) during the Weimar Republic. From 1920 to 1932, with only two brief interruptions, Braun was Minister President of the Free State ...

, was ousted by

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

, the new Chancellor, by means of a Presidential decree. Following the appointment of

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

as chancellor on 30 January 1933 by President Hindenburg, the SPD received 18.25% of the votes during the last (at least partially)

free elections on 5 March, gaining 120 seats. However, the SPD was unable to prevent the ratification of the

Enabling Act, which granted extraconstitutional powers to the government. The SPD was the only party to vote against the act (the KPD being already outlawed and its deputies were under arrest, dead, or in exile). Several of its deputies had been detained by the police under the provisions of the

Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Germ ...

, which suspended

civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

. Others suspected that the SPD would be next, and fled into exile.

[William Shirer, ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'' (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)] However, even if they had all been present, the Act would have still passed, as the 441 votes in favour would have still been more than the required two-thirds majority.

After the passing of the Enabling Act, dozens of SPD deputies were arrested, and several more fled into exile. Most of the leadership settled in

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Those that remained tried their best to appease the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

. On 19 May, the few SPD deputies who had not been jailed or fled into exile voted in favour of Hitler's foreign policy statement, in which he declared his willingness to renounce all offensive weapons if other countries followed suit. They also publicly distanced themselves from their brethren abroad who condemned Hitler's tactics.

It was to no avail. Over the course of the spring, the police confiscated the SPD's buildings, newspapers and property. On 21 June 1933, Interior Minister

Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

ordered the SPD closed down on the basis of the

Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Germ ...

, declaring the party "subversive and inimical to the State." All SPD deputies at the state and federal level were stripped of their seats, and all SPD meetings and publications were banned. Party members were also blacklisted from public office and the civil service. Frick took the line that the SPD members in exile were committing treason from abroad, while those still in Germany were helping them.

[

The party was a member of the ]Labour and Socialist International

The Labour and Socialist International (LSI; german: Sozialistische Arbeiter-Internationale, label=German, SAI) was an international organization of socialist and labour parties, active between 1923 and 1940. The group was established through a me ...

between 1923 and 1940.

Nazi era and SoPaDe (1933–1945)

Being the only party in the Reichstag to have voted against the Enabling Act, the SPD was banned in the summer of 1933 by the new

Being the only party in the Reichstag to have voted against the Enabling Act, the SPD was banned in the summer of 1933 by the new Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

. Many of its members were jailed or sent to Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

. An exile organization, known as Sopade, was established, initially in Prague. Others left the areas where they had been politically active and moved to other towns where they were not known.

Between 1936 and 1939 some SPD members fought in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

for the Republicans against Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

's Nationalists and the German Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

.

After the annexation of Czechoslovakia in 1938 the exile party resettled in Paris and, after the defeat of France in 1940, in London. Only a few days after the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in September 1939 the exiled SPD in Paris declared its support for the Allies and for the military removal from power of the Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

.

German Republic

From occupation to the Federal Republic (1946–1966)

The SPD was recreated after

The SPD was recreated after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1946 and admitted in all four occupation zones. In West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

, it was initially in opposition from the first election of the newly founded Federal Republic in 1949 until 1966. The party had a leftist period and opposed the republic's integration into Western structures, believing that this might diminish the chances for German reunification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

.

The SPD was somewhat hampered for much of the early history of the Federal Republic, in part because the bulk of its former heartland was now in the Soviet occupation sector, which later became East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

. In the latter area, the SPD was forced to merge with the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

(SED) in 1946. The few recalcitrant SPD members were quickly pushed out, leaving the SED as essentially a renamed KPD. In the British Occupation Zone, the SPD held a referendum on the issue of merging with the KPD, with 80% of party members rejecting such a fusion. This referendum was ignored by the newly formed SED.

Nonetheless, a few former SPD members held high posts in the East German government. Otto Grotewohl

Otto Emil Franz Grotewohl (; 11 March 1894 – 21 September 1964) was a German politician who served as the first prime minister of the German Democratic Republic (GDR/East Germany) from its foundation in October 1949 until his death in Septembe ...

served as East Germany's first prime minister from 1949 to 1964. For much of that time he retained the perspective of a left-wing social democrat, and publicly advocated a less repressive approach to governing during the time of the crackdown on the East German uprising of 1953. Friedrich Ebert, Jr., son of former president Ebert, served as mayor of East Berlin

East Berlin was the ''de facto'' capital city of East Germany from 1949 to 1990. Formally, it was the Soviet sector of Berlin, established in 1945. The American, British, and French sectors were known as West Berlin. From 13 August 1961 u ...

from 1949 to 1967; he'd reportedly been blackmailed into supporting the merger by using his father's role in the schism of 1918 against him.

During the fall of Communist rule in 1989, the SPD (first called SDP) was re-established as a separate party in East Germany (Social Democratic Party in the GDR

The Social Democratic Party in the GDR (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei in der DDR) was a reconstituted Social Democratic Party existing during the final phase of East Germany. Slightly less than a year after its creation it merged with its Wes ...

), independent of the rump SED, and then merged with its West German counterpart upon reunification.

Despite remaining out of office for much of the postwar period, the SPD were able to gain control of a number of local governments and implement progressive social reforms. As noted by Manfred Schmidt, SPD-controlled Lander governments were more active in the social sphere and transferred more funds to public employment and education than CDU/CSU-controlled Lander. During the mid-sixties, mainly SPD-governed Lander such as Hesse and the three city-states launched the first experiments with comprehensive schools as a means of as expanding educational opportunities. SPD local governments were also active in encouraging the post-war housing boom in West Germany, with some of the best results in housing construction during this period achieved by SPD-controlled Lander authorities such as West Berlin, Hamburg, and Bremen.Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Comm ...

, the SPD opposition were partly responsible for the establishment of the postwar welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

under the Adenauer Administration, having put parliamentary pressure on the CDU to carry out more progressive social policies during its time in office.

In the Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Comm ...

, The SPD aspired to be a “constructive opposition,” which expressed itself not only in the role it played in framing the significant amount of new legislation introduced in the first parliamentary terms of the Bundestag, but also in the fact that by far the biggest proportion of all laws were passed with the votes of SPD members. The SPD played a notable part in legislation on reforms to the national pensions scheme, the integration of refugees, and the building of public-sector housing. The SPD also had a high-profile “in judicial policy with the Public Prosecutor Adolf Arndt, in the parliamentary decision on the Federal Constitutional Court, and reparations for the victims of National Socialism.” In 1951, the law on the right of “co-determination” for employees in the steel, iron, and mining industries was passed with the combined votes of the SPD and CDU, and against those of the FDP.

Governing party (1966–1982)

In 1966 the coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) fell and a

In 1966 the coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) fell and a grand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political parties of opposing political ideologies unite in a coalition government. The term is most commonly used in countries where there are ...

between CDU/CSU and SPD was formed under the leadership of CDU Chancellor Kiesinger. The welfare state was considerably expanded, while social spending was almost doubled between 1969 and 1975.[ established active labour market intervention measures such as employment research, and offered “substantial state assistance to employees with educational aspirations.” Under the direction of the SPD Minister of Economics ]Karl Schiller

Karl August Fritz Schiller (24 April 1911 – 26 December 1994) was a German economist and politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). From 1966 to 1972, he was Federal Minister of Economic Affairs and from 1971 to 1972 Federal Minister o ...

, the federal government adopted Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

demand management

Demand management is a planning methodology used to forecast, plan for and manage the demand for products and services. This can be at macro-levels as in economics and at micro-levels within individual organizations. For example, at macro-lev ...

for the first time ever. Schiller called for legislation that would provide both his ministry and the federal government with greater authority to guide economic policy.incomes policy

Incomes policies in economics are economy-wide wage and price controls, most commonly instituted as a response to inflation, and usually seeking to establish wages and prices below free market level.

Incomes policies have often been resorted to ...

, but it did nevertheless ensure that collective bargaining took place “within a broadly agreed view of the direction of the economy and the relationships between full employment, output and inflation.” In 1969 the SPD won a majority for the first time since 1928 by forming a

In 1969 the SPD won a majority for the first time since 1928 by forming a social-liberal coalition

Social–liberal coalition (german: Sozialliberale Koalition) in the politics of Germany refers to a governmental coalition formed by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Free Democratic Party (FDP).

The term stems from social ...

with the FDP and led the federal government under Chancellors Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ger ...

and Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt (; 23 December 1918 – 10 November 2015) was a German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who served as the chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982.

Before becoming Ch ...

from 1969 until 1982. In its 1959 Godesberg Program

The Godesberg Program (german: Godesberger Programm) of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) was ratified in 1959 at a convention in the town of Bad Godesberg near Bonn. It represented a fundamental change in the orientation and goals of ...

, the SPD officially abandoned the concept of a workers' party and Marxist principles, while continuing to stress social welfare provision

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

. Although the SPD originally opposed West Germany's 1955 rearmament and entry into NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

while it favoured neutrality and reunification with East Germany, it now strongly supports German ties with the alliance.

A wide range of reforms were carried out under the Social-Liberal coalition

Social–liberal coalition (german: Sozialliberale Koalition) in the politics of Germany refers to a governmental coalition formed by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Free Democratic Party (FDP).

The term stems from social ...

, including, as summarised by one historical study

‘improved health and accident insurance, better unemployment compensation, rent control

Rent regulation is a system of laws, administered by a court or a public authority, which aims to ensure the affordability of housing and tenancies on the rental market for dwellings. Generally, a system of rent regulation involves:

*Price cont ...

, payments to families with children, subsidies to encourage savings and investments, and measures to “humanize the world of work” such as better medical care for on-the-job illnesses or injuries and mandated improvements in the work environment.'[A History of West Germany Volume 2: Democracy and its discontents 1963–1988 by Dennis L. Bark and David R. Gress]

Under the SDP-FDP coalition, social policies in West Germany took on a more egalitarian character and a number of important reforms were carried out to improve the prospects of previously neglected and underprivileged groups.social assistance

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

(excluding rent) as a percentage of average gross earnings of men in manufacturing industries rose during the Social-Liberal coalition's time in office, while social welfare provision was greatly extended, with pensions and health care opened up to large sections of the population.education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

,urban renewal

Urban renewal (also called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities. Urban renewal involves the clearing out of blighte ...

[A History of West Germany Volume 2: Democracy and its discontents 1963–1988 by Dennis L. Bark and David R. Gress.] In 1973, sickness benefits became available in cases where a parent had to care for a sick child.Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Comm ...

in June 1974, sought to modernise the working conditions of approximately 300 000 people who work at home by means of the following measures:air pollution

Air pollution is the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, or cause damage to the climate or to materials. There are many different type ...

, the Works’ Constitution Act and Personnel Representation Act strengthened the position of individual employees in offices and factories, and the Works’ Safety Law required firms to employ safety specialists and doctors.[My Life in Politics by Willy Brandt] while the new Factory Management Law (1972) extended co-determination at the factory level.youth councils

Youth councils are a form of youth voice engaged in community decision-making. Youth councils are appointed bodies that exist on local, state, provincial, regional, national, and international levels among governments, non governmental organisatio ...

.[

A new federal scale of charges for hospital treatment and a law on hospital financing were introduced to improve hospital treatment, the Hire Purchase Act entitled purchasers to withdraw from their contracts within a certain time limit, compensation for victims of violent acts became guaranteed by law, the Federal Criminal Investigation Office became a modern crime-fighting organisation, and the Federal Education Promotion Act was extended to include large groups of pupils attending vocational schools.]higher education

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after compl ...

,civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

and the Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

”.

As noted further by Henrich Potthoff and Susanne Miller

Susanne Miller (born Susanne Strasser: 14 May 1915 – 1 July 2008) was a Bulgarian-born left wing activist who for reasons of race and politics spent her early adulthood as a refugee in England. After 1945, she became known in West Germany as ...

, in their evaluation of the record of the SPD-FDP coalition,

“Ostpolitik and detente, the extension of the welfare safety net, and a greater degree of social liberality were the fruits of Social Democratic government during this period which served as a pointer to the future and increased the respect in which the federal republic was held, both in Europe and throughout the world.”

Opposition (1982–1998)

In 1982 the SPD lost power to the new CDU/CSU-FDP coalition under CDU Chancellor Helmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longes ...

who subsequently won four terms as chancellor. The Social Democrats were unanimous about the armament and environmental questions of that time, and the new party The Greens The Greens or Greens may refer to:

Current political parties

*Australian Greens, also known as ''The Greens''

*Greens of Andorra

* Greens of Bosnia and Herzegovina

*Greens of Burkina

* Greens (Greece)

* Greens of Montenegro

*Greens of Serbia

*Gree ...

was not ready for a coalition government then.

Gerhard Schröder and the consequences (1998–2005)

Kohl lost his last re-election bid in 1998 to his SPD challenger Gerhard Schröder

Gerhard Fritz Kurt "Gerd" Schröder (; born 7 April 1944) is a German lobbyist and former politician, who served as the chancellor of Germany from 1998 to 2005. From 1999 to 2004, he was also the Leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germa ...

, as the SPD formed a red-green coalition with The Greens to take control of the German federal government for the first time in 16 years.

Led by Gerhard Schröder

Gerhard Fritz Kurt "Gerd" Schröder (; born 7 April 1944) is a German lobbyist and former politician, who served as the chancellor of Germany from 1998 to 2005. From 1999 to 2004, he was also the Leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germa ...

on a moderate platform emphasizing the need to reduce unemployment, the SPD emerged as the strongest party in the September 1998 elections with 40.9% of the votes cast. Crucial for this success was the SPD's strong base in big cities and ''Bundesländer'' with traditional industries. Forming a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

with the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

, the SPD thus returned to power for the first time since 1982.

Oskar Lafontaine

Oskar Lafontaine (; born 16 September 1943) is a German politician. He served as Minister-President of the state of Saarland from 1985 to 1998, and was federal leader of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) from 1995 to 1999. He was the lead candid ...

, elected SPD chairman in November 1996 had in the run-up to the election forgone a bid for the SPD nomination for the chancellor candidacy, after Gerhard Schröder won a sweeping re-election victory as prime minister of his state of Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

and was widely believed to be the best chance for Social Democrats to regain the Chancellorship after 16 years in opposition. From the beginning of this teaming up between Party chair Lafontaine and chancellor candidate Schröder during the election campaign 1998, rumors in the media about their internal rivalry persisted, albeit always being disputed by the two. After the election victory Lafontaine joined the government as finance minister. The rivalry between the two party leaders escalated in March 1999 leading to the overnight resignation of Lafontaine from all his party and government positions. After staying initially mum about the reasons for his resignation, Lafontaine later cited strong disagreement with the alleged neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent f ...

and anti-social course Schröder had taken the government on. Schröder himself has never commented on the row with Lafontaine. It is known however, that they haven't spoken to each other ever since. Schröder succeeded Lafontaine as party chairman.

A number of progressive measures were introduced by the Schröder Administration during its first term in office. The parental leave scheme was improved, with full-time working parents legally entitled to reduce their working hours from 2001 onwards, while the child allowance was considerably increased, from €112 per month in 1998 to €154 in 2002. Housing allowances were also increased, while a number of decisions by the Kohl Government concerning social policy and the labour market were overturned, as characterised by the reversal of retrenchments in health policy and pension policy.

Changes introduced by the Kohl government on pensions, the continued payment of wages in the case of sickness, and wrongful dismissal were all rescinded.