History of the Panama Canal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The idea of the

The idea of the

The idea of a canal across Central America was revived during the early 19th century. In 1819, the Spanish government authorized the construction of a canal and the creation of a company to build it.

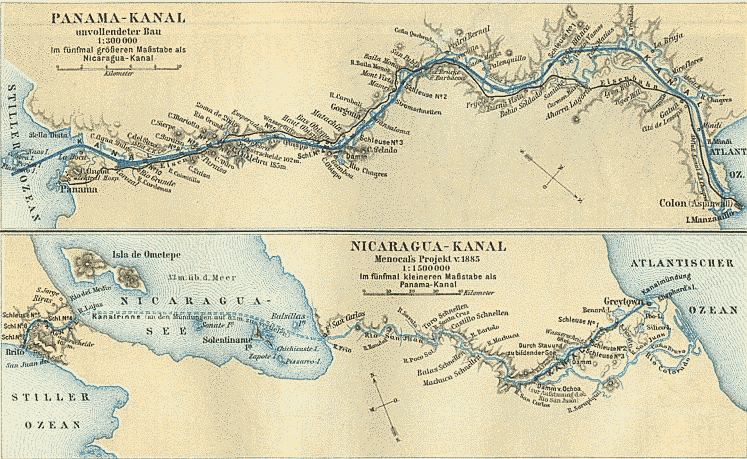

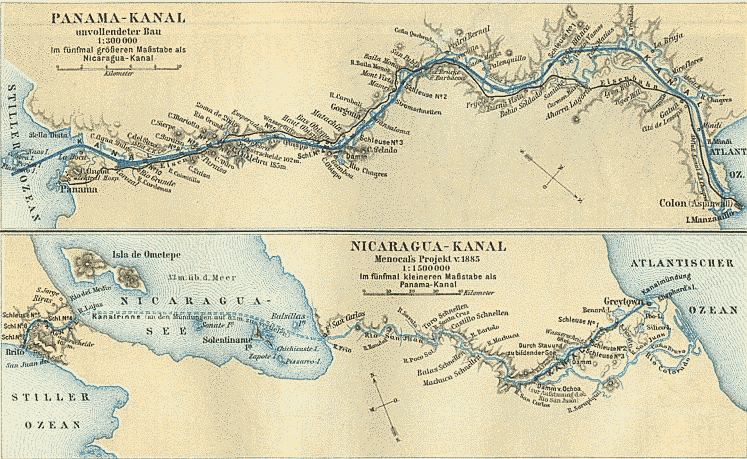

Although the project stalled for some time, a number of surveys were made between 1850 and 1875. They indicated that the two most-favorable routes were across Panama (then part of Colombia) and

The idea of a canal across Central America was revived during the early 19th century. In 1819, the Spanish government authorized the construction of a canal and the creation of a company to build it.

Although the project stalled for some time, a number of surveys were made between 1850 and 1875. They indicated that the two most-favorable routes were across Panama (then part of Colombia) and

After the 1869 completion of the

After the 1869 completion of the

Construction of the canal began on January 1, 1881, with digging at Culebra beginning on January 22.''Pre-Canal History''

Construction of the canal began on January 1, 1881, with digging at Culebra beginning on January 22.''Pre-Canal History''

from Global Perspectives A large labor force was assembled, numbering about 40,000 in 1888 (nine-tenths of whom were The company's collapse was a scandal in France, and the

The company's collapse was a scandal in France, and the

speech by Jean Jaurès, 1893 (a

Marxists.org Internet Archive

fro

CZ Brats

/ref>

The United States took control of the French property connected to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys during a small ceremony. The new Panama Canal Zone Control was overseen by the

The United States took control of the French property connected to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys during a small ceremony. The new Panama Canal Zone Control was overseen by the  Although chief engineer John Findley Wallace was pressured to resume construction,

Although chief engineer John Findley Wallace was pressured to resume construction,

The work done thus far was preparation, rather than construction. By the time Goethals took over, the construction infrastructure had been created or overhauled and expanded from the French effort and he was soon able to begin construction in earnest.

Goethals divided the project into three divisions: Atlantic, Central and Pacific. The Atlantic Division, under Major

The work done thus far was preparation, rather than construction. By the time Goethals took over, the construction infrastructure had been created or overhauled and expanded from the French effort and he was soon able to begin construction in earnest.

Goethals divided the project into three divisions: Atlantic, Central and Pacific. The Atlantic Division, under Major

One of the greatest barriers to a canal was the

One of the greatest barriers to a canal was the

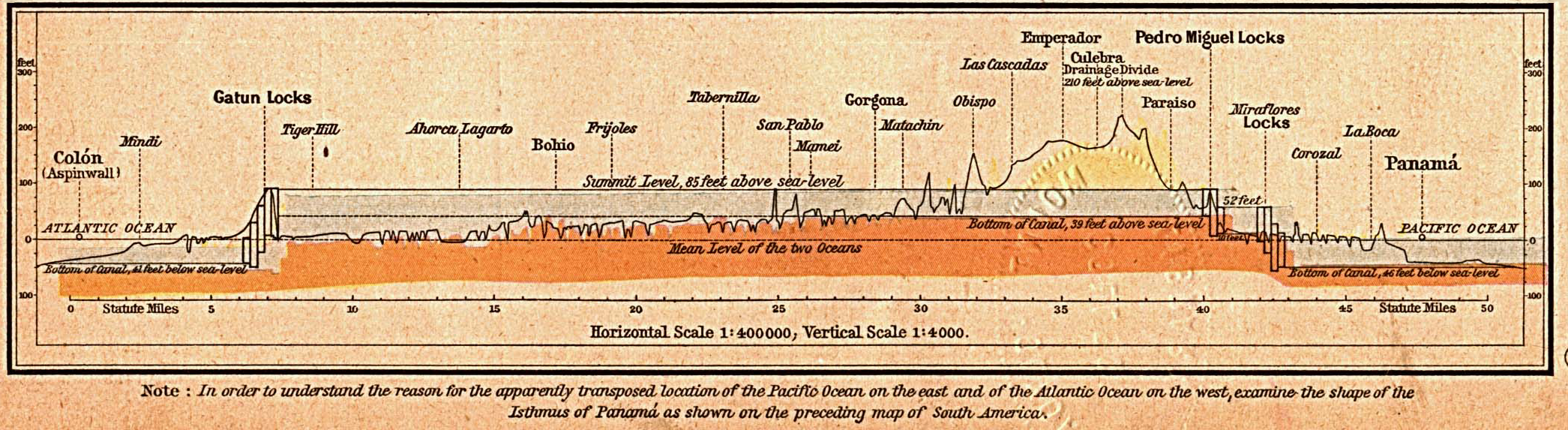

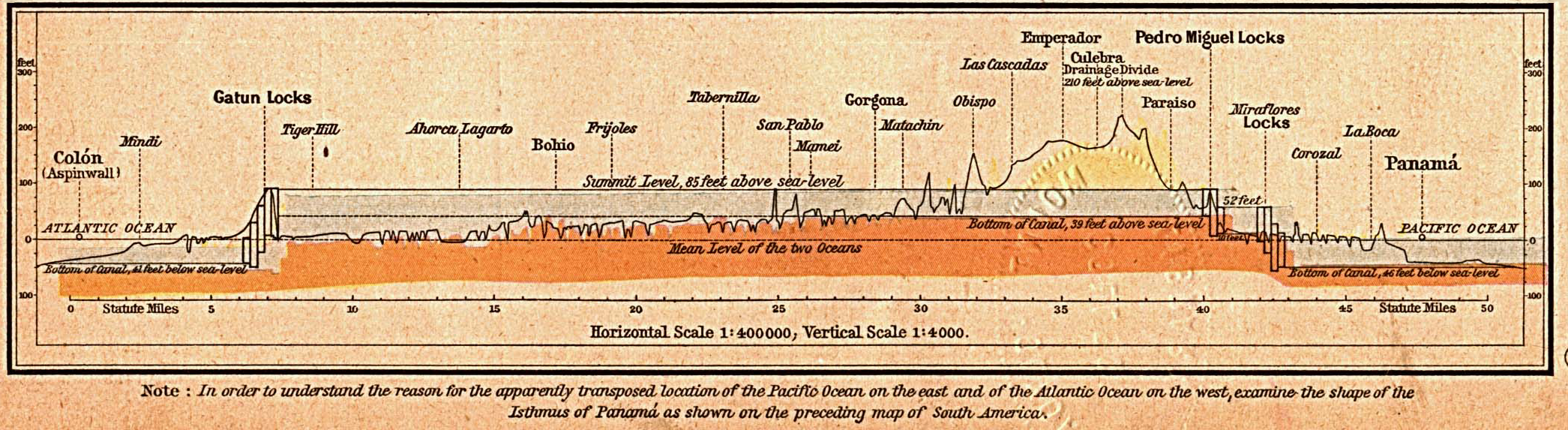

The original lock canal plan called for a two-step set of locks at Sosa Hill and a long Sosa Lake extending to Pedro Miguel. In late 1907, it was decided to move the Sosa Hill locks further inland to Miraflores, mostly because the new site provided a more stable construction foundation. The resulting small lake Miraflores became a fresh water supply for Panama City.

Building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun on August 24, 1909. The Gatun locks are built into a cutting into a hill bordering the lake, requiring the excavation of of material (mostly rock). The locks were made of of concrete, with an extensive system of electric railways and

The original lock canal plan called for a two-step set of locks at Sosa Hill and a long Sosa Lake extending to Pedro Miguel. In late 1907, it was decided to move the Sosa Hill locks further inland to Miraflores, mostly because the new site provided a more stable construction foundation. The resulting small lake Miraflores became a fresh water supply for Panama City.

Building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun on August 24, 1909. The Gatun locks are built into a cutting into a hill bordering the lake, requiring the excavation of of material (mostly rock). The locks were made of of concrete, with an extensive system of electric railways and

The canal was a technological marvel and an important strategic and economic asset to the US. It changed world shipping patterns, removing the need for ships to navigate the Drake Passage and

The canal was a technological marvel and an important strategic and economic asset to the US. It changed world shipping patterns, removing the need for ships to navigate the Drake Passage and  A total of over 75,000 people worked on the project; at the peak of construction, there were 40,000 workers. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

A total of of material was excavated in the American effort, including the approach channels at the canal ends. Adding the work by the French, the total excavation was about (over 25 times the volume excavated in the

A total of over 75,000 people worked on the project; at the peak of construction, there were 40,000 workers. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

A total of of material was excavated in the American effort, including the approach channels at the canal ends. Adding the work by the French, the total excavation was about (over 25 times the volume excavated in the

Alden P. Armagnac

CZ Brats

/ref>

notes fro

CZ Brats

/ref> These concerns led Congress to pass a resolution on May 1, 1936, authorizing a study of improving the canal's defenses against attack and expanding its capacity to handle large vessels. A special engineering section was created on July 3, 1937, to carry out the study. The section reported to Congress on February 24, 1939, recommending work to protect the existing locks and the construction of a new set of locks capable of carrying larger vessels than the existing locks could accommodate. On August 11, Congress authorized the work. Three new locks were planned, at Gatún, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores, parallel to the existing locks with new approach channels. The new locks would add a traffic lane to the canal, with each chamber long, wide and deep. They would be east of the existing Gatún locks and west of the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores locks. The first excavations for the new approach channels at Miraflores began on July 1, 1940, following the passage by Congress of an

"Wider than a Mile", Radio Netherlands Archives, December 31, 1999

/ref> Although concerns existed in the US and the shipping industry about the canal after the transfer, Panama has exercised good stewardship.Panama delivers a lesson to isolationists ''by Andrés Oppenheimer''

Although concerns existed in the US and the shipping industry about the canal after the transfer, Panama has exercised good stewardship.Panama delivers a lesson to isolationists ''by Andrés Oppenheimer''

/ref> According to ACP figures, canal income increased from $769 million in 2000 (the first year under Panamanian control) to $1.4 billion in 2006. Traffic through the canal increased from 230 million tons in 2000 to nearly 300 million tons in 2006. The number of accidents has decreased from an average of 28 per year in the late 1990s to 12 in 2005. Transit time through the canal averages about 30 hours, about the same as during the late 1990s. Canal expenses have increased less than revenue, from $427 million in 2000 to $497 million in 2006. On October 22, 2006, Panamanian citizens approved a

online

* Swilling, Mary C. "The Business of the Canal: The Economics and Politics of the Carter Administration’s Panama Canal Zone Initiative, 1978." ''Essays in Economic & Business History'' (2012) 22:275-89

online

* Williams, Mary Wilhelmine. ''Anglo-American Isthmian Diplomacy, 1815–1915'' (1916

online

(the ''Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty'')

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Panama Canal History of Panama

The idea of the

The idea of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

dates back to 1513, when Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

. The narrow land bridge between North and South America was a fine location to dig a water passage between the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

Oceans. The earliest European colonists recognized this, and several proposals for a canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface f ...

were made.

By the late nineteenth century, technological advances and commercial pressure allowed construction to begin in earnest. Noted canal engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

led the initial attempt by France to build a sea-level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised ...

canal. Beset by cost overruns due to the severe underestimation of the difficulties in excavating the rugged terrain, heavy personnel losses to tropical diseases, and political corruption in France surrounding the financing of the massive project, the canal was only partly completed.

Interest in a U.S.-led canal effort picked up as soon as France abandoned the project. Initially, the Panama site was politically unfavorable in the U.S. for a variety of reasons, including the taint of the failed French effort and the unfriendly attitude of the Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

n government (at the time, the owner of the land) towards the U.S. continuing the project. The U.S. first sought to construct a canal through Nicaragua instead.

French engineer and financier Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla

Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla () (26 July 1859 – 18 May 1940) was a French engineer and soldier. With the assistance of American lobbyist and lawyer William Nelson Cromwell, Bunau-Varilla greatly influenced Washington's decision concerning t ...

played a key role in changing American attitudes. Bunau-Varilla had a large stake in the failed French canal company and stood to profit on his investment only if the Panama Canal was completed. Extensive lobbying

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, whic ...

of American lawmakers, coupled with his support of a nascent independence movement among the Panamanian people, led to a simultaneous revolution in Panama and the negotiation of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty ( es, Tratado Hay-Bunau Varilla) was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named ...

which secured both independence for Panama and the right for the U.S. to lead a renewed effort to construct the canal. Colombia's response to the Panamanian independence movement was tempered by an American military presence; this is often cited as a classic example of the era of gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to ...

.

American success hinged on two factors. First was converting the original French sea-level plan to a more realistic lock

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

-controlled canal. The second was controlling the diseases which had decimated workers and management alike under the original French attempt. Initial chief engineer John Frank Stevens built much of the infrastructure necessary for later construction; slow progress on the canal itself led to his replacement by George Washington Goethals. Goethals oversaw the bulk of the excavation of the canal, including appointing Major David du Bose Gaillard to oversee the most daunting project, the Culebra Cut through the roughest terrain on the route. Almost as important as the engineering advances were the healthcare advances made during the construction, led by William C. Gorgas, an expert in controlling tropical diseases such as yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

. Gorgas was one of the first to recognize the role of mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

es in the spread of these diseases and, by focusing on controlling the mosquitoes, greatly improved worker conditions.

On 7 January 1914, the French crane boat ''Alexandre La Valley'' became the first to make the traverse, and on 1 April 1914 the construction was officially completed with the hand-over of the project from the construction company to the Canal Zone government. The outbreak of World War I caused the cancellation of any official "grand opening" celebration, but the canal officially opened to commercial traffic on 15 August 1914 with the transit of the '' SS Ancon''.

During World War II, the canal proved a vital part of American military strategy, allowing ships to transfer easily between the Atlantic and Pacific. Politically, the canal remained a territory of the United States until 1977, when the Torrijos–Carter Treaties began the process of transferring territorial control of the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the ter ...

to Panama, a process completed on 31 December 1999.

The Panama Canal continues to be a viable commercial venture and a vital link in world shipping, and is periodically upgraded. The Panama Canal expansion project started construction in 2007 and began commercial operation on 26 June 2016. The new locks allow the transit of larger Post-Panamax

Panamax and New Panamax (or Neopanamax) are terms for the size limits for ships travelling through the Panama Canal. The limits and requirements are published by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in a publication titled "Vessel Requirements". ...

and New Panamax

Panamax and New Panamax (or Neopanamax) are terms for the size limits for ships travelling through the Panama Canal. The limits and requirements are published by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in a publication titled "Vessel Requirements". ...

ships, which have greater cargo capacity than the original locks could accommodate.

French project

The idea of a canal across Central America was revived during the early 19th century. In 1819, the Spanish government authorized the construction of a canal and the creation of a company to build it.

Although the project stalled for some time, a number of surveys were made between 1850 and 1875. They indicated that the two most-favorable routes were across Panama (then part of Colombia) and

The idea of a canal across Central America was revived during the early 19th century. In 1819, the Spanish government authorized the construction of a canal and the creation of a company to build it.

Although the project stalled for some time, a number of surveys were made between 1850 and 1875. They indicated that the two most-favorable routes were across Panama (then part of Colombia) and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

, with a third route across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

in Mexico another option. The Nicaraguan route was surveyed.

Conception

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

, France thought that an apparently similar project to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans could be carried out with little difficulty. In 1876 a limited company, La Société Civile Internationale du Canal Interocéanique par l'isthme du Darien was created at the initiative of the Société de Géographie, dean of geography societies, to fill in gaps in the geographical knowledge of the Central American area for the purpose of building an interoceanic canal.

On March 20, 1878, the Société Civile obtained an exclusive 15 years concession from the Colombian government to build a canal across the isthmus of Panama, which at the time was a Department of Colombia; the waterway that would revert to the Colombian government after 99 years without compensation.

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

, who was in charge of the Suez Canal construction, headed the project. His enthusiastic leadership and his reputation as the man who had built the Suez Canal persuaded speculators and ordinary citizens to invest nearly $400 million in the project.

However, despite his previous success, Lesseps was not an engineer. The construction of the Suez Canal, essentially a ditch dug through a flat, sandy desert, presented few challenges. Although Central America's mountainous spine has a low point in Panama, it is still above sea level at its lowest crossing point. The sea-level canal proposed by de Lesseps would require a great deal of excavation through a variety of unstable rock, rather than Suez's sand.

Less-obvious barriers were the rivers crossing the canal, particularly the Chagres, which flows strongly during the rainy season. Since the water would be a hazard to shipping if it drained into the canal, a sea-level canal would require the river's diversion.

The most serious problem was tropical disease

Tropical diseases are diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropical and subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, which controls the insect population by f ...

s, particularly malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

and yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, whose methods of transmission were unknown at the time. The legs of hospital beds were placed in cans of water to keep insects from crawling up them, but the stagnant water was an ideal breeding place for mosquitoes (carriers of the diseases).

In May 1879, the Congrès International d'Etudes du Canal Interocéanique (International Congress for Study of an Interoceanic Canal), led by Lesseps, convened in Paris. Among the 136 delegates of 26 countries, 42 were engineers and made technical proposals before the congress. The others were speculators, politicians, and friends of Lesseps, for whom the purpose of this congress was only to launch fundraising by legitimizing Lesseps' own decision, based on the Lucien Bonaparte-Wyse

Lucien Napoléon Bonaparte-Wyse (13 January 1845 – 15 June 1909) was a French engineer. He was born in Paris as the son of Laetitia Bonaparte-Wyse, daughter of Lucien Bonaparte and estranged wife of the Irish politician Sir Thomas Wyse; L ...

and Armand Réclus plan, through a so-called international scientific approval, since he was convinced that a sea-level canal, dug through the mountainous spine of Central America, could be completed at least as easily as the Suez Canal.

In reality, only 19 engineers approved the chosen plan, and only 1 of those had visited Central America.

While the Americans abstained because of their own plan through Nicaragua, the five delegates from the French Society of Engineers all refused. Among them were Gustave Eiffel

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (born Bonickhausen dit Eiffel; ; ; 15 December 1832 – 27 December 1923) was a French civil engineer. A graduate of École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, he made his name with various bridges for the French railway ...

and Adolphe Godin de Lépinay, the general-secretary of the Société de Géographie, who was the only one to propose a lake-and-locks project. Designer in particular of the large gauge canal between Bordeaux and Narbonne, the road between Sétif

Sétif ( ar, سطيف, ber, Sṭif) is the capital of the Sétif Province in Algeria. It is one of the most important cities of eastern Algeria and the country as a whole, since it is considered the trade capital of the country. It is an inner ci ...

and Bougie, and of the railway lines connecting Philippeville

Philippeville (; wa, Flipveye) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. The Philippeville municipality includes the former municipalities of Fagnolle, Franchimont, Jamagne, Jamiolle, Merlemont, ...

to Constantine, Algeria

Constantine ( ar, قسنطينة '), also spelled Qacentina or Kasantina, is the capital of Constantine Province in northeastern Algeria. During Roman times it was called Cirta and was renamed "Constantina" in honor of emperor Constantine the G ...

, Algiers to Constantine, Athens to Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

, he also supervised the construction of the rail link between Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

and Córdoba, Mexico, losing two-thirds of his workers to tropical disease.

Godin de Lépinay's plan was to build a dam across the Chagres River in Gatún, near the Atlantic, and another on the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

, near the Pacific, to create an artificial lake accessed by locks. Digging less and avoiding unsanitary work and the danger of flooding was his priority, with an estimated lower cost of $100,000,000 () and 50,000 lives saved, as mentioned in the motivation for his negative review. All was said. The bankruptcy of the Lesseps project is described clearly, without ambiguity. It will be technical and financial, as Godin de Lépinay had planned. Unfortunately, his innovative plan, the only profitable as said by the Americans engineers, received no serious attention from the congress. Had it been adopted, the Panama Canal might well have been completed by the French instead of by the United States.

Following the congress, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama, in charge of the construction, whose president was Lesseps, acquired the Wyse Concession from the Société Civile.

The engineering congress estimated the Lesseps project's cost at $214 million; on February 14, 1880, an engineering commission revised the estimate to $168.6 million. Lesseps reduced this estimate twice, with no apparent justification: on February 20 to $131.6 million and on March 1 to $120 million. The congress estimated seven or eight years as the time required to complete the canal; Lesseps reduced this estimate to six years (the Suez Canal required ten).

The proposed sea-level canal would have a uniform depth of , a bottom width of and a width at water level of about ; the excavation estimate was . A dam was proposed at Gamboa to control flooding of the Chagres River, with channels to drain water away from the canal. However, the Gamboa dam was later found impracticable and the Chagres River problem was left unsolved.

Construction

Construction of the canal began on January 1, 1881, with digging at Culebra beginning on January 22.''Pre-Canal History''

Construction of the canal began on January 1, 1881, with digging at Culebra beginning on January 22.''Pre-Canal History''from Global Perspectives A large labor force was assembled, numbering about 40,000 in 1888 (nine-tenths of whom were

afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the tr ...

workers from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

). Although the project attracted good, well-paid French engineers, retaining them was difficult due to disease. The death toll from 1881 to 1889 was estimated at over 22,000, of whom as many as 5,000 were French citizens.

By 1885 it had become clear to many that a sea-level canal was impractical, and an elevated canal with locks was preferable; de Lesseps resisted, and a lock canal plan was not adopted until October 1887. By this time increasing mortality rates, as well as financial and engineering problems coupled with frequent flood

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrol ...

s and mudslide

A mudflow or mud flow is a form of mass wasting involving fast-moving flow of debris that has become liquified by the addition of water. Such flows can move at speeds ranging from 3 meters/minute to 5 meters/second. Mudflows contain a signific ...

s, indicated that the project was in serious trouble. Work continued under the new plan until May 15, 1889, when the company went bankrupt and the project was suspended. After eight years the canal was about two-fifths completed, and about $234.8 million had been spent.

The company's collapse was a scandal in France, and the

The company's collapse was a scandal in France, and the antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

Edouard Drumont exploited the role of two Jewish speculators in the affair. One hundred and four legislators were found to have been involved in the corruption, and Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

was commissioned by the French parliament to conduct an inquiry which was completed in 1893.''On the Panama Scandal''speech by Jean Jaurès, 1893 (a

Marxists.org Internet Archive

New Panama Canal Company

It soon became clear that the only way to recoup expenses for the stockholders was to continue the project. A new concession was obtained from Colombia, and in 1894 the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama was created to finish the canal. To comply with the terms of the contract, work began immediately on the Culebra excavation while a team of engineers began a comprehensive study of the project. They eventually settled on a plan for a two-level, lock-based canal. The new effort never gained traction, mainly because of US speculation that a canal through Nicaragua would render one through Panama useless. The most men employed on the new project was 3,600 (in 1896), primarily to comply with the terms of the concession and to maintain the existing excavation and equipment in saleable condition. The company had already begun looking for a buyer, with an asking price of $109 million. In the US, a congressionalIsthmian Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission (often known as the ICC) was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given cont ...

was established in 1899 to examine possibilities for a Central American canal and recommend a route. In November 1901, the commission reported that a US canal should be built through Nicaragua unless the French were willing to sell their holdings for $40 million. The recommendation became law on June 28, 1902, and the New Panama Canal Company was compelled to sell at that price.''The French Failure''fro

CZ Brats

/ref>

Results

Although the French effort was effectively doomed to failure from the beginning due to disease and a lack of understanding of the engineering difficulties, it was not entirely futile. The old and new companies excavated of material, of which was taken from the Culebra Cut. The old company dredged a channel from Panama Bay to the port at Balboa, and the channel dredged on the Atlantic side (known as the French canal) was useful for bringing in sand and stone for the locks and spillway concrete at Gatún. Detailed surveys and studies (particularly those carried out by the new canal company) and machinery, including railroad equipment and vehicles, aided the later American effort. The French lowered the summit of the Culebra Cut along the canal route by , from . An estimated of excavation, valued at about $25.4 million, and equipment and surveys valued at about $17.4 million were usable by the Americans.Nicaraguan canal

The 1848 discovery of gold in California and the rush of would-be miners stimulated US interest in building a canal between the oceans. In 1887, aUnited States Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

regiment surveyed canal possibilities in Nicaragua. Two years later, the Maritime Canal Company was asked to begin a canal in the area and chose Nicaragua. The company lost money in the panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

, and its work in Nicaragua ceased. In 1897 and 1899, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

charged a canal commission with researching possible construction; Nicaragua was chosen as the location both times.

Although the Nicaraguan canal proposal was made redundant by the American takeover of the French Panama Canal project, increases in shipping volume and ship sizes have revived interest in the project. A canal across Nicaragua accommodating post-Panamax

Panamax and New Panamax (or Neopanamax) are terms for the size limits for ships travelling through the Panama Canal. The limits and requirements are published by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in a publication titled "Vessel Requirements". ...

ships or a rail link carrying containers between ports on either coast have been proposed.

United States

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

believed that a US-controlled canal across Central America was a vital strategic interest of the country. This idea gained wide circulation after the destruction of the USS ''Maine'' in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

on February 15, 1898. Reversing a Walker Commission decision in favor of a Nicaraguan canal, Roosevelt encouraged the acquisition of the French Panama Canal effort. George S. Morison was the only commission member who argued for the Panama location. The purchase of the French-held land for $40 million was authorized by the June 28, 1902 Spooner Act. Since Panama was then part of Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

, Roosevelt began negotiating with that country to obtain the necessary rights. In early 1903 the Hay–Herrán Treaty

The Hay–Herrán Treaty was a treaty signed on January 22, 1903, between United States Secretary of State John M. Hay of the United States and Tomás Herrán of Colombia. Had it been ratified, it would have allowed the United States a renewab ...

was signed by both nations, but the Senate of Colombia

The Senate of the Republic of Colombia ( es, Senado de la República de Colombia) is the upper house of the Congress of Colombia, with the lower house being the House of Representatives. The Senate has 108 members elected for concurrent (non- ...

failed to ratify the treaty.

Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the US Navy would assist their fight for independence. Panama declared its independence on November 3, 1903, and the USS ''Nashville'' impeded Colombian interference. The victorious Panamanians gave the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the ter ...

on February 23, 1904, for $10 million in accordance with the November 18, 1903 Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty ( es, Tratado Hay-Bunau Varilla) was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named ...

.

Takeover

The United States took control of the French property connected to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys during a small ceremony. The new Panama Canal Zone Control was overseen by the

The United States took control of the French property connected to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys during a small ceremony. The new Panama Canal Zone Control was overseen by the Isthmian Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission (often known as the ICC) was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given cont ...

(ICC) during construction.

The first step taken by the US government was to place all the canal workers under the new administration. The operation was maintained at minimum strength to comply with the canal concession and keep the machinery in working order. The US inherited a small workforce and an assortment of buildings, infrastructure and equipment, much of which had been neglected for fifteen years in the humid jungle environment. There were no facilities in place for a large workforce, and the infrastructure was crumbling.

Cataloguing assets was a large job; it took many weeks to card-index available equipment. About 2,150 buildings had been acquired, many of which were uninhabitable; housing was an early problem, and the Panama Railway was in a state of decay. However, much equipment (such as locomotives, dredges and other floating equipment) was still serviceable.

Although chief engineer John Findley Wallace was pressured to resume construction,

Although chief engineer John Findley Wallace was pressured to resume construction, red tape

Red tape is an idiom referring to regulations or conformity to formal rules or standards which are claimed to be excessive, rigid or redundant, or to bureaucracy claimed to hinder or prevent action or decision-making. It is usually applied to ...

from Washington stifled his efforts to obtain heavy equipment and caused friction between Wallace and the ICC. He and chief sanitary officer William C. Gorgas were frustrated by delay, and Wallace resigned in 1905. He was replaced by John Frank Stevens, who arrived on July 26, 1905. Stevens quickly realized that serious investment in infrastructure was necessary and determined to upgrade the railway, improve sanitation in Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is loca ...

and Colón, renovate the old French buildings and build hundreds of new ones for housing. He then began the difficult task of recruiting the large labor force required for construction. Stevens' approach was to press ahead first and obtain approval later. He improved drilling and dirt-removal equipment at the Culebra Cut for greater efficiency, revising the inadequate provisions in place for soil disposal.

No decision had been made about whether the canal should be a lock

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

or a sea-level one; the ongoing excavation would be useful in either case. In late 1905, President Roosevelt sent a team of engineers to Panama to investigate the relative merits of both types in cost and time. Although the engineers voted eight to five in favor of a sea-level canal, Stevens and the ICC opposed the plan; Stevens' report to Roosevelt was instrumental in convincing the president of the merits of a lock canal and Congress concurred. In November 1906 Roosevelt visited Panama to inspect the canal's progress, the first trip outside the United States by a sitting president.

Whether contract employees or government workers would build the canal was controversial. Bids for the canal's construction were opened in January 1907, and Knoxville, Tennessee-based contractor William J. Oliver was the low bidder. Stevens disliked Oliver, and vehemently opposed his choice. Although Roosevelt initially favored the use of a contractor, he eventually decided that army engineers should carry out the workDuVal, Miles P. (1947) ''And the Mountains Will Move: The Story of the Building of the Panama Canal''. Stanford University Press. and appointed Major George Washington Goethals as chief engineer (under Stevens' direction) in February 1907. Stevens, frustrated by government inaction and the army involvement, resigned and was replaced by Goethals.

Workforce

The US relied on a stratified workforce to build the canal. High-level engineering jobs, clerical positions, skilled labor and jobs in supporting industries were generally reserved for Americans, with manual labor primarily by cheap immigrant labor. These jobs were initially filled by Europeans, primarily from Spain, Italy and Greece, many of whom were radical and militant due to political turmoil in Europe. The US then decided to recruit primarily from the British and French West Indies, and these workers provided most of the manual labor on the canal.Robert H. Zieger. "Builders and Dreamers." Reviews in American History 38, no. 3 (2010): 513–519.Living conditions

The Canal Zone originally had minimal facilities for entertainment and relaxation for the canal workers apart from saloons; as a result, alcohol abuse was a great problem. The inhospitable conditions resulted in many American workers returning home each year. A program of improvements was implemented. Clubhouses were built, managed by theYMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

, with billiard, assembly and reading rooms, bowling alleys, darkrooms for camera clubs, gymnastic equipment, ice cream parlors, soda fountains and a circulating library A circulating library (also known as lending libraries and rental libraries) lent books to subscribers, and was first and foremost a business venture. The intention was to profit from lending books to the public for a fee.

Overview

Circulating li ...

. Member dues were ten dollars a year, with the remaining upkeep (about $7,000 at the larger clubhouses) paid by the ICC. The commission built baseball fields and arranged rail transportation to games; a competitive league soon developed. Semi-monthly Saturday-night dances were held at the Hotel Tivoli, which had a spacious ballroom.

These measures influenced life in the Canal Zone; alcohol abuse fell, with saloon business declining by 60 percent. The number of workers leaving the project each year dropped significantly.

US construction

The work done thus far was preparation, rather than construction. By the time Goethals took over, the construction infrastructure had been created or overhauled and expanded from the French effort and he was soon able to begin construction in earnest.

Goethals divided the project into three divisions: Atlantic, Central and Pacific. The Atlantic Division, under Major

The work done thus far was preparation, rather than construction. By the time Goethals took over, the construction infrastructure had been created or overhauled and expanded from the French effort and he was soon able to begin construction in earnest.

Goethals divided the project into three divisions: Atlantic, Central and Pacific. The Atlantic Division, under Major William L. Sibert

Major General William Luther Sibert (October 12, 1860 – October 16, 1935) was a senior United States Army officer who commanded the 1st Division on the Western Front during World War I.

Early life and education

Sibert was born in Gadsden, ...

, was responsible for construction of the breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island, Antarctica

* Breakwater Islands, Nunavut, Canada

* Br ...

at the entrance to Limon Bay, the Gatún locks and their approach channel, and the Gatun Dam

The Gatun Dam is a large earthen dam across the Chagres River in Panama, near the town of Gatun. The dam, constructed between 1907 and 1913, is a crucial element of the Panama Canal; it impounds the artificial Gatun Lake, which in turn carries sh ...

. The Pacific Division (under Sydney B. Williamson, the only civilian division head) was responsible for the Pacific entrance to the canal, including a breakwater in Panama Bay, the approach channel, and the Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks and their associated dams. The Central Division, under Major David du Bose Gaillard, was responsible for everything in between. It had arguably the project's greatest challenge: excavating the Culebra Cut (known as the Gaillard Cut from 1915 to 2000), which involved cutting through the continental divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not c ...

down to above sea level.

By August 1907, 765,000 m³ (1,000,000 cubic yards) per month was being excavated; this set a record for the rainy season; soon afterwards this doubled, before increasing again. At the peak of production, 2,300,000 m³ (3,000,000 cubic yards) were being excavated per month (the equivalent amount of spoil from the Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (french: Tunnel sous la Manche), also known as the Chunnel, is a railway tunnel that connects Folkestone (Kent, England, UK) with Coquelles ( Hauts-de-France, France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover ...

every 3½ months).

Culebra Cut

One of the greatest barriers to a canal was the

One of the greatest barriers to a canal was the continental divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not c ...

, which originally rose to above sea level at its highest point. The effort to cut through this barrier of rock was one of the greatest challenges faced by the project.

Goethals arrived at the canal with Major David du Bose Gaillard of the US Army Corps of Engineers. Gaillard was placed in charge of the canal's Central Division, which stretched from the Pedro Miguel locks to the Gatun Dam

The Gatun Dam is a large earthen dam across the Chagres River in Panama, near the town of Gatun. The dam, constructed between 1907 and 1913, is a crucial element of the Panama Canal; it impounds the artificial Gatun Lake, which in turn carries sh ...

, and dedicated himself to getting the Culebra Cut (as it was then known) excavated.

The scale of the work was massive. Six thousand men worked in the cut, drilling holes in which a total of of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

were placed to break up the rock (which was then removed by as many as 160 trains per day). Landslides were frequent, due to the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

and weakening of the rock's underlying iron strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

. Although the scale of the job and the frequent, unpredictable slides generated chaos, Gaillard provided quiet, clear-sighted leadership.

On May 20, 1913, Bucyrus steam shovels made a passage through the Culebra Cut at the level of the canal bottom. The French effort had reduced the summit to over a relatively narrow width; the Americans had lowered this to above sea level over a greater width, and had excavated over of material. About of this material was in addition to the planned excavation, due to landslides. Dry excavation ended on September 10, 1913; a January slide had added of earth, but it was decided that this loose material would be removed by dredging when the cut was flooded.

Dams

Twoartificial lakes

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including contro ...

are key parts of the canal: Gatun and Miraflores Lakes. Four dams were constructed to create them. Two small dams at Miraflores impound Miraflores Lake, and a dam at Pedro Miguel encloses the south end of the Culebra Cut (essentially an arm of Lake Gatun). The Gatun Dam

The Gatun Dam is a large earthen dam across the Chagres River in Panama, near the town of Gatun. The dam, constructed between 1907 and 1913, is a crucial element of the Panama Canal; it impounds the artificial Gatun Lake, which in turn carries sh ...

is the main dam blocking the original course of the Chagres River, creating Gatun Lake.

The Miraflores dams are an earth dam connecting the Miraflores Locks in the west and a concrete spillway dam east of the locks. The concrete dam has eight floodgates, similar to those on the Gatun spillway

A spillway is a structure used to provide the controlled release of water downstream from a dam or levee, typically into the riverbed of the dammed river itself. In the United Kingdom, they may be known as overflow channels. Spillways ensure th ...

. The earthen, Pedro Miguel dam extends from a hill in the west to the lock. Its face is protected by rock riprap at the water level. The largest and most challenging of the dams is the Gatun Dam. This earthen dam, thick at the base and long along the top, was the largest of its kind in the world when the canal opened.

Locks

The original lock canal plan called for a two-step set of locks at Sosa Hill and a long Sosa Lake extending to Pedro Miguel. In late 1907, it was decided to move the Sosa Hill locks further inland to Miraflores, mostly because the new site provided a more stable construction foundation. The resulting small lake Miraflores became a fresh water supply for Panama City.

Building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun on August 24, 1909. The Gatun locks are built into a cutting into a hill bordering the lake, requiring the excavation of of material (mostly rock). The locks were made of of concrete, with an extensive system of electric railways and

The original lock canal plan called for a two-step set of locks at Sosa Hill and a long Sosa Lake extending to Pedro Miguel. In late 1907, it was decided to move the Sosa Hill locks further inland to Miraflores, mostly because the new site provided a more stable construction foundation. The resulting small lake Miraflores became a fresh water supply for Panama City.

Building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun on August 24, 1909. The Gatun locks are built into a cutting into a hill bordering the lake, requiring the excavation of of material (mostly rock). The locks were made of of concrete, with an extensive system of electric railways and aerial lift

An aerial lift, also known as a cable car or ropeway, is a means of cable transport in which ''cabins'', ''cars'', ''gondolas'', or open chairs are hauled above the ground by means of one or more cables. Aerial lift systems are frequently employe ...

s transporting concrete to the lock-construction sites.

The Pacific-side locks were finished first: the single flight at Pedro Miguel in 1911, and Miraflores in May 1913. The seagoing tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

''Gatun'', an Atlantic-entrance tug used to haul barges, traversed the Gatun locks on September 26, 1913. The trip was successful, although the valves were controlled manually; the central control board was not yet ready.

Opening

On October 10, 1913, the dike at Gamboa which had kept the Culebra Cut isolated from Gatun Lake was demolished; the detonation was made telegraphically by PresidentWoodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

in Washington. On January 7, 1914, the ''Alexandre La Valley'', an old French crane boat, became the first ship to make a complete transit of the Panama Canal under its own steam after working its way across during the final stages of construction.

As construction wound down, the canal team began to disperse. Thousands of workers were laid off, and entire towns were disassembled or demolished. Chief sanitary officer William C. Gorgas, who left to fight pneumonia in the South African gold mines, became surgeon general of the Army. On April 1, 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission disbanded, and the zone was governed by a Canal Zone Governor; the first governor was George Washington Goethals.

Although a large celebration was planned for the canal's opening, the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

forced the cancellation of the main festivities and it became a modest local affair. The Panama Railway steamship , piloted by Captain John A. Constantine (the canal's first pilot), made the first official transit on August 15, 1914. With no international dignitaries in attendance, Goethals followed the ''Ancon'' progress by railroad.

Summary

The canal was a technological marvel and an important strategic and economic asset to the US. It changed world shipping patterns, removing the need for ships to navigate the Drake Passage and

The canal was a technological marvel and an important strategic and economic asset to the US. It changed world shipping patterns, removing the need for ships to navigate the Drake Passage and Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

. The canal saves a total of about on a sea trip from New York to San Francisco.

Its anticipated military significance of the canal was proven during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when the canal helped restore the devastated United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

.''Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal 1903–1979'', John Major, Cambridge University Press, 1993 (a comprehensive history of U.S. policy, from Teddy Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter) Some of the largest ships the United States had to send through the canal were aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s, particularly ''Essex'' class; they were so large that although the locks could accommodate them, the lampposts along the canal had to be removed.

The Panama Canal cost the United States about $375 million, including $10 million paid to Panama and $40 million paid to the French company. Although it was the most expensive construction project in US history to that time, it cost about $23 million less than the 1907 estimate despite landslides and an increase in the canal's width. An additional $12 million was spent on fortifications.

A total of over 75,000 people worked on the project; at the peak of construction, there were 40,000 workers. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

A total of of material was excavated in the American effort, including the approach channels at the canal ends. Adding the work by the French, the total excavation was about (over 25 times the volume excavated in the

A total of over 75,000 people worked on the project; at the peak of construction, there were 40,000 workers. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

A total of of material was excavated in the American effort, including the approach channels at the canal ends. Adding the work by the French, the total excavation was about (over 25 times the volume excavated in the Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (french: Tunnel sous la Manche), also known as the Chunnel, is a railway tunnel that connects Folkestone (Kent, England, UK) with Coquelles ( Hauts-de-France, France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover ...

project).

Of the three presidents whose terms spanned the construction period, Theodore Roosevelt is most associated with the canal and Woodrow Wilson presided over its opening. However, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

may have given the canal its greatest impetus for the longest time. Taft visited Panama five times as Roosevelt's secretary of war and twice as president. He hired John Stevens and later recommended Goethals as Stevens' replacement. Taft became president in 1909, when the canal was half finished, and was in office for most of the remainder of the work. However, Goethals later wrote: "The real builder of the Panama Canal was Theodore Roosevelt".

The following words by Roosevelt are displayed in the rotunda of the canal's administration building in Balboa:

It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.David du Bose Gaillard died of a

brain tumor

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and seco ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

on December 5, 1913, at age 54. Promoted to colonel only a month earlier, Gaillard never saw the opening of the canal whose creation he directed. The Culebra Cut (as it was originally known) was renamed the Gaillard Cut on April 27, 1915, in his honor. A plaque commemorating Gaillard's work stood over the cut for many years; in 1998 it was moved to the administration building, near a memorial to Goethals.

Third-lane plans

In the Treaty of the Danish West Indies, the United States purchased theVirgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas Vírgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Cro ...

in 1917 in part to defend the Panama Canal. As the situation in Europe deteriorated during the late 1930s, the US again became concerned about its ability to move warships between the oceans. The largest US battleships already had problems with the canal locks, and there were concerns about the locks being incapacitated by bombing. These concerns were validated by several US Navy fleet problems, which showed that the canal's defenses were inadequate.''Enlarging the Panama Canal''Alden P. Armagnac

CZ Brats

/ref>

notes fro

CZ Brats

/ref> These concerns led Congress to pass a resolution on May 1, 1936, authorizing a study of improving the canal's defenses against attack and expanding its capacity to handle large vessels. A special engineering section was created on July 3, 1937, to carry out the study. The section reported to Congress on February 24, 1939, recommending work to protect the existing locks and the construction of a new set of locks capable of carrying larger vessels than the existing locks could accommodate. On August 11, Congress authorized the work. Three new locks were planned, at Gatún, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores, parallel to the existing locks with new approach channels. The new locks would add a traffic lane to the canal, with each chamber long, wide and deep. They would be east of the existing Gatún locks and west of the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores locks. The first excavations for the new approach channels at Miraflores began on July 1, 1940, following the passage by Congress of an

appropriations bill

An appropriation, also known as supply bill or spending bill, is a proposed law that authorizes the expenditure of government funds. It is a bill that sets money aside for specific spending. In some democracies, approval of the legislature is ne ...

on June 24, 1940. The first dry excavation at Gatún began on February 19, 1941. Considerable material was excavated before the project was abandoned, and the approach channels can still be seen paralleling the original channels at Gatún and Miraflores.

In 2006, the Autoridad del Canal de Panamá (the Panama Canal Authority, or ACP) proposed a plan creating a third lane of locks using part of the abandoned 1940s approach canals. Following a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

, work began in 2007 and the expanded canal began commercial operations on June 26, 2016. After a two-year delay, the new locks allow the transit of Panamax

Panamax and New Panamax (or Neopanamax) are terms for the size limits for ships travelling through the Panama Canal. The limits and requirements are published by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in a publication titled "Vessel Requirements". ...

ships (which have a greater cargo capacity than the original locks can handle). The first ship to cross the canal through the third set of locks was a Panamax container ship

A container ship (also called boxship or spelled containership) is a cargo ship that carries all of its load in truck-size intermodal containers, in a technique called containerization. Container ships are a common means of commercial intermoda ...

, the Chinese-owned ''Cosco Shipping Panama''. The cost of the expansion was estimated at $5.25 billion.

Transfer to Panama

After construction, the canal and the Canal Zone surrounding it were administered by the United States. On September 7, 1977, US PresidentJimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty setting in motion the process of transferring control of the canal to Panama. The treaty became effective on October 2, 1979, providing for a 20-year period in which Panama would have increasing responsibility for canal operations before complete US withdrawal on December 31, 1999. Since then, the canal has been administered by the Panama Canal Authority (Autoridad de Canal de Panama, or ACP).

The transfer of the canal came under heavy attack from conservatives, especially the American Conservative Union

The American Conservative Union (ACU) is an American political organization that advocates for conservative policies, ranks politicians based on their level of conservatism, and organizes the Conservative Political Action Conference. Founded o ...

, the Conservative Caucus, the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, Citizens for the Republic, the American Security Council, the Young Republicans, the National Conservative Political Action Committee, the Council for National Defense, Young Americans for Freedom, the Council for Inter-American Security, and the Campus Republican Action Organization. The treaty narrowly passed with the required 2/3 vote in the Senate. Though Panamanians welcomed the return of sovereignty over the Panama Canal, many people at the time also expressed fears of the possible negative economic repercussions./ref>

Although concerns existed in the US and the shipping industry about the canal after the transfer, Panama has exercised good stewardship.Panama delivers a lesson to isolationists ''by Andrés Oppenheimer''

Although concerns existed in the US and the shipping industry about the canal after the transfer, Panama has exercised good stewardship.Panama delivers a lesson to isolationists ''by Andrés Oppenheimer''/ref> According to ACP figures, canal income increased from $769 million in 2000 (the first year under Panamanian control) to $1.4 billion in 2006. Traffic through the canal increased from 230 million tons in 2000 to nearly 300 million tons in 2006. The number of accidents has decreased from an average of 28 per year in the late 1990s to 12 in 2005. Transit time through the canal averages about 30 hours, about the same as during the late 1990s. Canal expenses have increased less than revenue, from $427 million in 2000 to $497 million in 2006. On October 22, 2006, Panamanian citizens approved a

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

to expand the canal.

Former US Ambassador to Panama Linda Ellen Watt, who served from 2002 to 2005, said that the canal operation in Panamanian hands has been "outstanding". "The international shipping community is quite pleased", Watt added.

See also

* Corozal "Silver" Cemetery – a cemetery near Panama City dedicated to workers on the Panama Canal. *Latin America–United States relations

Historically speaking, bilateral relations between the various countries of atin Americaand the United States of America have been multifaceted and complex, at times defined by strong regional cooperation and at others filled with economic and ...

* Operation Pelikan

References

Further reading

* Collin, Richard H. ''Theodore Roosevelt's Caribbean: The Panama Canal, the Monroe Doctrine, & the Latin American Context'' (Louisiana State U. Press, 1990), 520pp *Greene, Julie. (2009). ''The Canal Builders: Making America's Empire at the Panama Canal''. New York: The Penguin Press. * Lafeber, Walter. ''The Panama Canal: The Crisis in Historical Perspective'' (3rd ed. 1990), the standard scholarly account of diplomacy * McCullough, David. (1977). '' The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914''. New York: Simon & Schuster. * Parker, Matthew. (2008).''Panama Fever: The Epic Story of One of the Greatest Human Achievements of All Time—The Building of the Panama Canal.'' Doubleday. * Smith, Gaddis. ''Morality Reason, and Power: American Diplomacy in the Carter Years'' (1986) pp 110–15. * Strong, Robert A. "Jimmy Carter and the Panama Canal Treaties." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' (1991) 21.2: 269-28online

* Swilling, Mary C. "The Business of the Canal: The Economics and Politics of the Carter Administration’s Panama Canal Zone Initiative, 1978." ''Essays in Economic & Business History'' (2012) 22:275-89

online

* Williams, Mary Wilhelmine. ''Anglo-American Isthmian Diplomacy, 1815–1915'' (1916

online

Contemporary magazines

* Includes c. 1905 construction photos. * *External links

* National Archives of Japan(the ''Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty'')

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Panama Canal History of Panama

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

Industrial history

Panama Canal

Panama–United States relations

Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

Articles containing video clips