History of the Northern Territory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The History of the Northern Territory began over 60,000 years ago when

and possibly 300 years prior to that. Europeans first sighted the coast of the future Territory in the 17th century. British groups made attempts to settle the coastal regions of the Territory from 1824 onwards, but no settlement proved successful until the establishment of

Although sparse, the archaeological record of the Northern Territory provides evidence of settlement around 60,000 years ago at Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, although there is controversy surrounding the thermoluminescent dating of these sites. During this period, sea levels were lower than at present, and Australia and

Although sparse, the archaeological record of the Northern Territory provides evidence of settlement around 60,000 years ago at Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, although there is controversy surrounding the thermoluminescent dating of these sites. During this period, sea levels were lower than at present, and Australia and

Sailors from the islands north of Australia were trading with northern coast of Australia before the Dutch arrived in the Indonesian Archipelago around 1600 AD. First the Baiini sea gypsy families came to trade for pearls and for oyster and turtle shell,. The Baiini brought their entire families and built houses of stone and ironbark. They planted rice in Warrimiri country and Gumatj country. Later the people who traded out of Makassar (now

Sailors from the islands north of Australia were trading with northern coast of Australia before the Dutch arrived in the Indonesian Archipelago around 1600 AD. First the Baiini sea gypsy families came to trade for pearls and for oyster and turtle shell,. The Baiini brought their entire families and built houses of stone and ironbark. They planted rice in Warrimiri country and Gumatj country. Later the people who traded out of Makassar (now

The British made a third attempt in 1838, establishing Fort Victoria at

The British made a third attempt in 1838, establishing Fort Victoria at

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

settled the region. Makassan

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, Medan ...

traders began trading with the indigenous people of the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

for trepang from at least the 18th century onwardand possibly 300 years prior to that. Europeans first sighted the coast of the future Territory in the 17th century. British groups made attempts to settle the coastal regions of the Territory from 1824 onwards, but no settlement proved successful until the establishment of

Port Darwin

Port Darwin is the port in Darwin, Northern Territory, in northern Australia. The port has operated in a number of locations, including Stokes Hill Wharf, Cullen Bay and East Arm Wharf. In 2015, a 99-year lease was granted to the Chinese-owned ...

in 1869.

Prehistory

Although sparse, the archaeological record of the Northern Territory provides evidence of settlement around 60,000 years ago at Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, although there is controversy surrounding the thermoluminescent dating of these sites. During this period, sea levels were lower than at present, and Australia and

Although sparse, the archaeological record of the Northern Territory provides evidence of settlement around 60,000 years ago at Malakunanja and Nauwalabila, although there is controversy surrounding the thermoluminescent dating of these sites. During this period, sea levels were lower than at present, and Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

along with large tracts of what is now the Timor Sea

The Timor Sea ( id, Laut Timor, pt, Mar de Timor, tet, Tasi Mane or ) is a relatively shallow sea bounded to the north by the island of Timor, to the east by the Arafura Sea, and to the south by Australia.

The sea contains a number of reefs ...

formed one single landmass.

Abundant and complex rock art testifies to the rich cultural and spiritual lives of the original inhabitants of the Northern Territory, and in many areas of the Northern Territory there is a cultural continuum between the earliest inhabitants and the indigenous population today. Rock art

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also m ...

is extremely difficult to date with any reliability, and it can also be difficult to identify a linear sequence of art due to the reworking and reinterpretation of older art by younger generations.

However archaeologists have been able to identify three distinct phases of art: pre-estuarine (dry climate and extinct animals), estuarine (rising sea levels

Rising may refer to:

* Rising, a stage in baking - see Proofing (baking technique)

*Elevation

* Short for Uprising, a rebellion

Film and TV

* "Rising" (''Stargate Atlantis''), the series premiere of the science fiction television program ''Starg ...

and marine fauna), and freshwater (freshwater fauna, moving into 'historical' subjects such as Makassan

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, Medan ...

traders, and European technology e.g. guns). Rock art also demonstrates cultural and technological changes. For instance, boomerangs give way to broad spearthrowers which give way to long spearthrowers, which give way to guns and boats.

The dingo

The dingo (''Canis familiaris'', ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient ( basal) lineage of dog found in Australia. Its taxonomic classification is debated as indicated by the variety of scienti ...

was introduced from Asia around 3,500 years ago and quickly became integrated into Aboriginal societies, where they played a role in hunting and provided warmth on cold nights.

Makassan and Baiini trade

Sailors from the islands north of Australia were trading with northern coast of Australia before the Dutch arrived in the Indonesian Archipelago around 1600 AD. First the Baiini sea gypsy families came to trade for pearls and for oyster and turtle shell,. The Baiini brought their entire families and built houses of stone and ironbark. They planted rice in Warrimiri country and Gumatj country. Later the people who traded out of Makassar (now

Sailors from the islands north of Australia were trading with northern coast of Australia before the Dutch arrived in the Indonesian Archipelago around 1600 AD. First the Baiini sea gypsy families came to trade for pearls and for oyster and turtle shell,. The Baiini brought their entire families and built houses of stone and ironbark. They planted rice in Warrimiri country and Gumatj country. Later the people who traded out of Makassar (now Ujung Pandang

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, Meda ...

) came in search of trepang, which was prized for its culinary and medicinal values in Chinese markets. The Makassar came only to collect trepang, never setting up permanent camps with crops, apart from dropped tamarind seeds that sprouted. The annual Makassan voyages to the Kimberly and Arnhem Land dated from the 1700s, and ended in 1907 thanks to Australian regulations. However, there are reports of visits perhaps 300 years prior to that, and extended from the Kimberleys in the west, to the east of Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary i ...

. The Makassans had extensive contact with the indigenous tribes of the Northern Territory, trading cloth, knives, alcohol, and tobacco for the right to fish in Territory waters and use aboriginal labour.

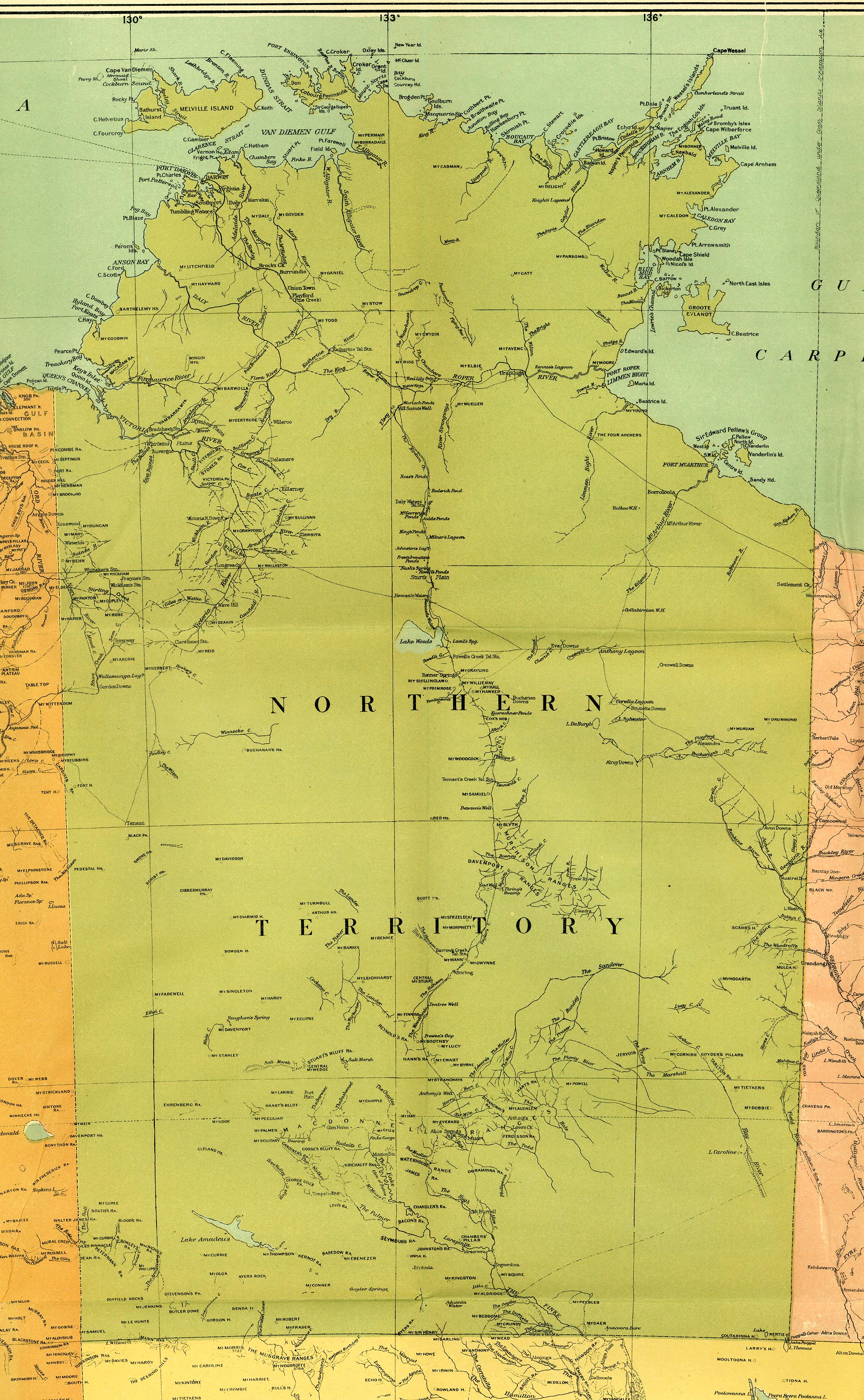

European exploration and settlement

The first recorded sighting of the Northern Territory coastline was byDutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

navigator Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ), sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz., was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. Janszoon served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 16031611 and 16121616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of S ...

aboard the ship in 1606. Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

and numerous French navigators also charted the coast, naming many prominent features. Captain Phillip Parker King

Rear Admiral Phillip Parker King, FRS, RN (13 December 1791 – 26 February 1856) was an early explorer of the Australian and Patagonian coasts.

Early life and education

King was born on Norfolk Island, to Philip Gidley King and Anna ...

also made surveys of the coast.

Following the European settlement of Australian in 1788, four unsuccessful attempts were made to settle coastal areas of the Northern Territory prior to the establishment of Darwin. On 30 September 1824, British Captain James Gordon Bremer established Fort Dundas

Fort Dundas was a short-lived British settlement on Melville Island between 1824 and 1828 in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. It was the first of four British settlement attempts in northern Australia before Goyder's survey a ...

on Melville Island as a part of the Colony of New South Wales

The Colony of New South Wales was a colony of the British Empire from 1788 to 1901, when it became a State of the Commonwealth of Australia. At its greatest extent, the colony of New South Wales included the present-day Australian states of ...

. Fort Dundas was the first settlement in Northern Australia. However, poor relations with the Tiwi people

The Tiwi people (or Tunuvivi) are one of the many Aboriginal groups of Australia. Nearly 2,000 Tiwi people live on Bathurst and Melville Islands, which make up the Tiwi Islands, lying about from Darwin. The Tiwi language is a language isola ...

, cyclone

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an an ...

s, and other difficulties of tropical living, led to the Fort being abandoned in 1828. A second settlement was established on the Cobourg Peninsula

The Cobourg Peninsula is located east of Darwin in the Northern Territory, Australia. It is deeply indented with coves and bays, covers a land area of about , and is virtually uninhabited with a population ranging from about 20 to 30 in five ...

at Raffles Bay

Raffles Bay is a bay on the northern coast of the Cobourg Peninsula of the Top End of the Northern Territory of Australia. It was named in 1818 by explorer Phillip Parker King after Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the founder of Singapore. It is ...

on 18 June 1827. Fort Wellington was founded by Captain James Stirling, but it was also abandoned in 1829.

The British made a third attempt in 1838, establishing Fort Victoria at

The British made a third attempt in 1838, establishing Fort Victoria at Port Essington

Port Essington is an inlet and historic site located on the Cobourg Peninsula in the Garig Gunak Barlu National Park in Australia's Northern Territory. It was the site of an early attempt at British settlement, but now exists only as a remo ...

on 27 October 1838. James Bremer was also in command of the new settlement, which was visited in July 1839 by and her crew. Bremer left in 1839 and, following his departure, conditions in the settlement deteriorated. The Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n naturalist and explorer Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, (23 October 1813 – c. 1848) was a German explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.Ken Eastwood,'Cold case: Leichhardt's dis ...

, travelled from Moreton Bay, overland to Port Essington. An unsuccessful migration scheme was tried, and the first Catholic priest, Father Angelo Confalonieri, arrived in the area in 1846. However, the settlement disbanded on 1 December 1849.

European explorers made their last great, often arduous, and sometimes tragic, expeditions into the interior of Australia during the second half of the 19th century – some with the official sponsorship of the colonial authorities and others commissioned by private investors. By 1850, large areas of the inland were still unknown to Europeans. Trailblazers like Edmund Kennedy

Edmund Besley Court Kennedy J. P. (5 September 1818 – December 1848) was an explorer in Australia in the mid nineteenth century. He was the Assistant-Surveyor of New South Wales, working with Sir Thomas Mitchell. Kennedy explored the interio ...

, and Ludwig Leichhardt, had met tragic ends during the 1840s, attempting to fill in the gaps, but explorers remained ambitious to discover new lands for agriculture or answer scientific questions. Surveyors also acted as explorers and the colonies sent out expeditions to discover the best routes for lines of communication. The size of expeditions varied considerably, from small parties of just two or three, to large, well-equipped teams, led by gentlemen explorers assisted by smiths, carpenters, labourers and Aboriginal guides, and accompanied by horses, camels or bullocks.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart

John McDouall Stuart (7 September 18155 June 1866), often referred to as simply "McDouall Stuart", was a Scottish explorer and one of the most accomplished of all Australia's inland explorers.

Stuart led the first successful expedition to tra ...

succeeded in traversing Central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was a telegraphy system to send messages over long distances using cables and electric signals. It spanned between Darwin, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia, and Adelaide, the capital o ...

.Flannery, Tim (1998). ''The Explorers''. Text Publishing. Vague: add page number. Stuart wanted the newly discovered region to be called "Alexandra Land", in honour of the Princess of Wales. The name was gazetted in 1865 applying to the portion South of 16°S of what is now the Northern Territory. For some time, Northern Territory including Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land is a historical region of the Northern Territory of Australia, with the term still in use. It is located in the north-eastern corner of the territory and is around from the territory capital, Darwin. In 1623, Dutch East India Compa ...

referred to the region North of that.

In 1863, the Northern Territory was annexed by South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

by letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

. Following the annexation, a fourth attempt at settlement occurred in 1864 at Escape Cliffs

Escape Cliffs is a place on the northern coast of the Northern Territory of Australia and the site of the fourth of a series of four failed attempts to establish permanent settlement in Australia's Top End. The previous attempts were at Fort ...

, about from present-day Darwin. Colonel Boyle Travers Finniss

Boyle Travers Finniss (18 August 1807 – 24 December 1893) was the first premier of South Australia, serving from 24 October 1856 to 20 August 1857.

Early life

Finniss was born at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, Southern Africa, and lived in ...

was responsible for the settlement. There were numerous confrontations with the local Marananggu Aborigines, and when he was recalled to Adelaide in 1867, the settlement disbanded. The South Australian government also tried to find sites for additional settlements, sending explorer John McKinlay

John McKinlay (26 August 1819 – 31 December 1872)

,

On 1 January 1911, a decade after federation, the Northern Territory was separated from South Australia and transferred to Australian government control, under the South Australian ''Northern Territory Surrender Act 1907'', and the federal ''Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910''. The ''Northern Territory (Administration) Act'' provided that there would be an Administrator appointed by the Governor-General to administer the Territory on behalf of the Australian Government, subject to any instructions given to him by the appropriate Minister from time to time.

In late 1912, there was growing sentiment that the name "Northern Territory" was unsatisfactory. The names "Kingsland" (after

On 1 January 1911, a decade after federation, the Northern Territory was separated from South Australia and transferred to Australian government control, under the South Australian ''Northern Territory Surrender Act 1907'', and the federal ''Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910''. The ''Northern Territory (Administration) Act'' provided that there would be an Administrator appointed by the Governor-General to administer the Territory on behalf of the Australian Government, subject to any instructions given to him by the appropriate Minister from time to time.

In late 1912, there was growing sentiment that the name "Northern Territory" was unsatisfactory. The names "Kingsland" (after

, Australian Department of the Environment and Water Resources

Australia declared war on

Australia declared war on

Northern Territory documents

- National Archives of Australia. {{Northern Territory

,

Adelaide River

The Adelaide River is a river in the Northern Territory of Australia.

Course and features

The river rises in the Litchfield National Park and flows generally northwards to Clarence Strait, joined by eight tributaries including the west branc ...

, but he had no success.

Uluru

Uluru (; pjt, Uluṟu ), also known as Ayers Rock ( ) and officially gazetted as UluruAyers Rock, is a large sandstone formation in the centre of Australia. It is in the southern part of the Northern Territory, southwest of Alice Spring ...

and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872, during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was a telegraphy system to send messages over long distances using cables and electric signals. It spanned between Darwin, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia, and Adelaide, the capital o ...

. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles

William Ernest Powell Giles (20 July 1835 – 13 November 1897), best known as Ernest Giles, was an Australian explorer who led five major expeditions to parts of South Australia and Western Australia.

Early life

Ernest Giles was born in Bri ...

and William Gosse William Gosse may refer to:

*William Gosse (explorer)

William Christie Gosse (11 December 1842–12 August 1881), was an Australian explorer, who was born in Hoddesdon,"Gosse, William Christie (1842–1881)". ''Australian Dictionary of Biogr ...

were the first European explorers to the area. While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon, naming it Mount Olga for Queen Olga of Württemberg, and in the following year, Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honor of the Premier of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

Sir Henry Ayers. The barren desert lands of Central Australia disappointed the Europeans as unpromising for pastoral expansion, but would later come to be appreciated as emblematic of Australia.

Finally, on 5 February 1869, George Goyder

George Woodroffe Goyder (24 June 1826 – 2 November 1898) was a surveyor in the Colony of South Australia during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

He rose rapidly in the civil service, becoming Assistant Surveyor-General by 185 ...

, the Surveyor-General of South Australia, established a small settlement of 135 men and women at Port Darwin

Port Darwin is the port in Darwin, Northern Territory, in northern Australia. The port has operated in a number of locations, including Stokes Hill Wharf, Cullen Bay and East Arm Wharf. In 2015, a 99-year lease was granted to the Chinese-owned ...

. Goyder named the settlement Palmerston, after the British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston. In 1870, the first poles for the Overland Telegraph

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was a telegraphy system to send messages over long distances using cables and electric signals. It spanned between Darwin, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia, and Adelaide, the capital o ...

were erected in Darwin. The construction of the Overland Telegraph, connecting Australia to the rest of the world, led to more exploration of the interior of the Territory, and the discovery of gold at Pine Creek in the 1880s drove further economic development.

20th century

On 1 January 1911, a decade after federation, the Northern Territory was separated from South Australia and transferred to Australian government control, under the South Australian ''Northern Territory Surrender Act 1907'', and the federal ''Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910''. The ''Northern Territory (Administration) Act'' provided that there would be an Administrator appointed by the Governor-General to administer the Territory on behalf of the Australian Government, subject to any instructions given to him by the appropriate Minister from time to time.

In late 1912, there was growing sentiment that the name "Northern Territory" was unsatisfactory. The names "Kingsland" (after

On 1 January 1911, a decade after federation, the Northern Territory was separated from South Australia and transferred to Australian government control, under the South Australian ''Northern Territory Surrender Act 1907'', and the federal ''Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910''. The ''Northern Territory (Administration) Act'' provided that there would be an Administrator appointed by the Governor-General to administer the Territory on behalf of the Australian Government, subject to any instructions given to him by the appropriate Minister from time to time.

In late 1912, there was growing sentiment that the name "Northern Territory" was unsatisfactory. The names "Kingsland" (after King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

and to correspond with Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

), "Centralia" and "Territoria" were proposed, with Kingsland becoming the preferred choice in 1913. However, the name change never went ahead.

For a brief time between 1926 and 1931, the Northern Territory was divided into North Australia

North Australia can refer to a short-lived former British colony, a former federal territory of the Commonwealth of Australia, or a proposed state which would replace the current Northern Territory.

Colony (1846–1847)

A colony of North Austr ...

and Central Australia

Central Australia, also sometimes referred to as the Red Centre, is an inexactly defined region associated with the geographic centre of Australia. In its narrowest sense it describes a region that is limited to the town of Alice Springs and ...

at the 20th parallel south of latitude. Soon after that, under the Kimberley Scheme, parts of the Northern Territory were considered as a possible site for the establishment of a Jewish Homeland

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction ...

, but it was understandably considered to be the "''Unpromised Land

The Promised Land ( he, הארץ המובטחת, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, أرض الميعاد, translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

''".

Central Australia

Between 1918 and 1921, large areas of the Territory and adjacent states were classified asAboriginal reserve

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-sanctioned settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th c ...

s and sanctuaries for remaining nomadic populations who had hitherto had little contact with Europeans. In 1920, the area including Uluru

Uluru (; pjt, Uluṟu ), also known as Ayers Rock ( ) and officially gazetted as UluruAyers Rock, is a large sandstone formation in the centre of Australia. It is in the southern part of the Northern Territory, southwest of Alice Spring ...

, in Anangu territory, was declared an Aboriginal Reserve under the Aboriginals Ordinance (Northern Territory). Nevertheless, small numbers of non-Aboriginal people continued to visit the area, including missionaries, adventurers, native welfare patrol officers and dingo scalpers. In 1931, the gold prospector Harold Lasseter

Lewis Harold Bell Lasseter (27 September 1880 - 31 January 1931), also known as Harold Lasseter, was an Australian gold prospector who claimed to have found a fabulously rich gold reef in central Australia.

Life

Lasseter was born in 1880 at Ba ...

died in the area, while searching for his famous reef of gold. The return of pastoralists to the region created conflict with the Aborigines, amid competition for scarce resources. In 1940, the reserve was reduced in size to facilitate access for gold prospecting.

Tourists had begun arriving at Uluru in 1936. A vehicular track was made in 1948. Post-war assimilation policies anticipated that the Pitjantjatjara

The Pitjantjatjara (; or ) are an Aboriginal people of the Central Australian desert near Uluru. They are closely related to the Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra and their languages are, to a large extent, mutually intelligible (all are vari ...

and Yankunytjatjara people would assimilate into Australian society and welfare authorities moved them to Aboriginal settlements to facilitate this process.Uluṟu - Kata Tjuṯa National Park - Growing tourism in the Park, Australian Department of the Environment and Water Resources

Caledon Bay Crisis

TheCaledon Bay crisis

The Caledon Bay crisis, refers to a series of killings at Caledon Bay in the Northern Territory of Australia during 1932–34, referred to in the press of the day as Caledon Bay murder(s). Five Japanese trepang fishers were killed by Aboriginal ...

of 1932–34 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the 'frontier' between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. It began with the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu women, and was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

to the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established following passage of the '' Judiciary Act 1903''. ...

was launched. Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thomson was dispatched by the government to live among the Yolngu.

World War Two

Australia declared war on

Australia declared war on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

following its invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

in 1939. After Japan entered the war in 1941, the Northern Territory came under direct attack. With most of Australia's best forces committed to fight against Hitler in the Middle East, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US naval base in Hawaii, on 8 December 1941 (eastern Australia time). The British battleship and battle cruiser sent to defend Singapore were sunk soon afterwards. British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. ...

quickly collapsed, shocking the Australian nation. After the Fall of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire ...

, Australian Prime Minister

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the princi ...

Curtin predicted that the "battle for Australia

The Battle for Australia is a contested historiographical term used to claim a coordinated link between a series of battles near Australia during the Pacific War of the Second World War alleged to be in preparation for a Japanese invasion of ...

" would follow and, on 19 February, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times.

Aboriginal Land Rights

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

had struggled for rights to fair wages and land. An important event in this struggle was the strike and walk off by the Gurindji people

The Gurindji are an Aboriginal Australian people of northern Australia, southwest of Katherine in the Northern Territory's Victoria River region.

Language and culture

Gurindji is one of the eastern Ngumbin languages, in the Ngumbin-Yapa s ...

at Wave Hill, cattle station in 1966. The Commonwealth Government of Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

set up the Woodward Royal Commission in February 1973 set to inquire into how land rights might be achieved in the Northern Territory. Justice Woodward's first report in July 1973 recommended that a Central Land Council

The Central Land Council (CLC) is a land council that represents the Aboriginal peoples of the southern half of the Northern Territory of Australia (NT), predominantly with regard to land issues. it is one of four land councils in the Northern T ...

and a Northern Land Council

The Northern Land Council (NLC) is a land council representing the Aboriginal peoples of the Top End of the Northern Territory of Australia, with its head office in Darwin.

While the NLC was established in 1974, its origins began in the strugg ...

be established in order to present to him the views of Aboriginal people. In response to the report of the Royal Commission a Land Rights Bill was drafted, but the Whitlam Government was dismissed before it was passed.

The ''Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976

The ''Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976'' (ALRA) is Australian federal government legislation that provides the basis upon which Aboriginal Australian people in the Northern Territory can claim rights to land based on traditi ...

'' was eventually passed by the Fraser Government on 16 December 1976 and began operation on Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port ...

, that is 26 January 1977.

Self-government

In 1978 the Territory was granted responsible government, with a Legislative Assembly headed by a Chief Minister, publishing official notices in its own ''Government Gazette''. TheCountry Liberal Party

The Country Liberal Party of the Northern Territory (CLP) is a centre-right political party in Australia's Northern Territory. In local politics it operates in a two-party system with the Australian Labor Party (ALP). It also contests federal ...

(CLP) was established in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

in 1974 by supporters of the Liberal and Country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, whi ...

Parties of Australia living in the Territory; thereafter it enjoyed considerable electoral success. The Party has contested general elections in the Territory since 1974

Major events in 1974 include the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis and the resignation of United States President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. In the Middle East, the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War determined politics; ...

and saw unbroken electoral success from 1974 until 2001 when it lost office to the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms t ...

. Clare Martin

Clare Majella Martin (born 15 June 1952) is a former Australian journalist and politician. She was elected to the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly in a shock by-election win in 1995. She was appointed Opposition Leader in 1999, and won ...

won a surprise victory at the 2001 territory election, becoming the first Labor Party, and first female Chief Minister. The ALP member for Arafura Marion Scrymgour, became the Labor Party Deputy Chief Minister of the Northern Territory from November 2007 until February 2009. She was the highest-ranked indigenous person in government in Australia's history. She was also the first indigenous woman to be elected to the Northern Territory Parliament.

The 2012 Northern Territory general election

The Northern Territory general election was held on Saturday 25 August 2012, which elected all 25 members of the Legislative Assembly in the unicameral Northern Territory Parliament. The 11-year Labor Party government led by Chief Minister ...

ended 11 years of Labor rule and saw Terry Mills defeat the Incumbent Labor Government led by Paul Henderson

Paul Garnet Henderson, (born January 28, 1943) is a Canadian former professional ice hockey player. A left winger, Henderson played 13 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for the Detroit Red Wings, Toronto Maple Leafs and Atlanta Fla ...

. The victory was also notable for the support it achieved from indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

in pastoral and remote electorates. Large swings were achieved in remote Territory electorates (where the indigenous population comprised around two thirds of voters) and a total of five Aboriginal CLP candidates won election to the Assembly. Among the Aboriginal candidates elected was high-profile Aboriginal activist Bess Price

Bess Nungarrayi Price (born 22 October 1960) is an Aboriginal Australian activist and politician. She was a Country Liberal Party member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly from 2012 to 2016, representing the electorate of Stuart, an ...

and former Labor member Alison Anderson. Anderson was appointed Minister for Indigenous Advancement. In her first ministerial statement on the status of Aboriginal communities in the Territory she said the CLP would focus on improving education and on helping create real jobs for indigenous people. However, Alison Anderson resigned from the CLP in 2014, along with two other indigenous MPs, briefly becoming an independent once again. On 27 April 2014 the three MLAs had joined the Palmer United Party, with Anderson serving as parliamentary leader

Recent history

The Northern Territory was briefly in 1995-6 one of the few places in the world with legal voluntary euthanasia, until the Federal Parliament overturned the legislation. Before the overriding legislation was enacted, three people had been voluntarily euthanased by DrPhilip Nitschke

Philip Haig Nitschke (; born 8 August 1947) is an Australian humanist, author, former physician, and founder and director of the pro-euthanasia group EXIT (Australia), Exit International. He campaigned successfully to have a legal euthanasia la ...

.

In 2007, the Australian Federal Government implemented the Northern Territory National Emergency Response (also referred to as "the intervention") a controversial policy package that enforced welfare, law enforcement and land provision measures to address allegations of child sexual abuse and neglect in Northern Territory Aboriginal Communities. The initiative attracted controversy for its implementation - including the overturning of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, the deployment of over 600 Australian Defence Force personnel into Aboriginal communities, lack of community consultation and compulsory acquisition of townships. It has been condemned as nothing more than a hasty reaction to allegations made in 2006 regarding child sexual assault in Aboriginal communities. As well as this, some view it as another attempt by the government to control these communities.

See also

* History of Darwin * Timeline of Darwin HistoryReferences

External links

Northern Territory documents

- National Archives of Australia. {{Northern Territory