The

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(23 January 1368 – 25 April 1644), officially the Great Ming, founded by the peasant rebel leader

Zhu Yuanzhang

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (), courtesy name Guorui (), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty of China, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts i ...

, known as the

Hongwu Emperor

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (), courtesy name Guorui (), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty of China, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts i ...

, was an

imperial dynasty of China. It was the successor to the

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

and the predecessor of the short-lived

Shun dynasty

The Shun dynasty (), officially the Great Shun (), was a short-lived Chinese dynasty that existed during the Ming–Qing transition. The dynasty was founded in Xi'an on 8 February 1644, the first day of the lunar year, by Li Zicheng, the leade ...

, which was in turn succeeded by the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. At its height, the Ming dynasty had a population of 160 million people,

[Fairbank, 128.] while some assert the population could actually have been as large as 200 million.

Ming rule saw the construction of a vast

navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

and a

standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or ...

of 1,000,000 troops.

[Ebrey et al., ''East Asia'', 271.] Although private maritime trade and official tribute missions from China took place in previous dynasties, the size of the tributary fleet under the

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

admiral

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

in the 15th century surpassed all others in grandeur. There were enormous projects of construction, including the restoration of the

Grand Canal, the restoration of the

Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against Eurasian noma ...

as it is seen today, and the establishment of the

Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is a palace complex in Dongcheng District, Beijing, China, at the center of the Imperial City of Beijing. It is surrounded by numerous opulent imperial gardens and temples including the Zhongshan Park, the sacrifi ...

in Beijing during the first quarter of the 15th century. The Ming dynasty is, for many reasons, generally known as a period of stable effective government. It had long been the most secure and unchallenged ruling house that China had known up until that time. Its institutions were generally preserved by the following Qing dynasty. The civil service dominated government to an unprecedented degree at this time. During the Ming dynasty, the territory of China expanded (and in some cases also retracted) greatly. For a brief period during the Ming dynasty northern Vietnam was included in the Ming dynasty's territory. Other important developments include the moving of the capital from

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

to

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

.

Outside of metropolitan areas, Ming China was divided into thirteen provinces for administrative purposes. These provinces were divided along traditional and to a degree also natural lines. These include

Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

,

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

,

Huguang,

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

,

Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

,

Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

,

Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

,

Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is a ...

,

Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-leve ...

,

Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

,

Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

,

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

and

Guizhou

Guizhou (; Postal romanization, formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in the Southwest China, southwest region of the China, People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the pr ...

. These provinces were vast areas, each being at least as large as England. The longest Ming reign was that of the

Wanli Emperor

The Wanli Emperor (; 4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun (), was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was th ...

, who ruled for forty eight years. (1572–1620). The shortest was his son's reign, the

Taichang Emperor

The Taichang Emperor (; 28 August 1582 – 26 September 1620), personal name Zhu Changluo (), was the 15th Emperor of the Ming dynasty. He was the eldest son of the Wanli Emperor and succeeded his father as emperor in 1620. However, his reign c ...

, who ruled for only one month (in 1620).

Founding of the dynasty

Revolt and rebel rivalry

The

Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

-led

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

(1279–1368) ruled before the establishment of the Ming dynasty. Alongside institutionalized ethnic discrimination against the

Han people

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive var ...

that stirred resentment and rebellion, other explanations for the Yuan's demise included overtaxing areas hard-hit by crop failure,

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

, and massive flooding of the

Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

as a result of the abandonment of irrigation projects.

Consequently, agriculture and the economy were in shambles and rebellion broke out among the hundreds of thousands of peasants called upon to work on repairing the dikes of the Yellow River.

[Gascoigne, 150.]

A number of ethnic Han groups revolted, including the

Red Turbans in 1351. The Red Turbans were affiliated with the

Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

secret society of the

White Lotus

The White Lotus () is a syncretic religious and political movement which forecasts the imminent advent of the "King of Light" (), i.e., the future Buddha Maitreya. As White Lotus sects developed, they appealed to many Han Chinese who found sol ...

, which propagated

Manichean

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (AD ...

beliefs in the struggle of good against evil and worship of the

Maitreya Buddha

Maitreya ( Sanskrit: ) or Metteyya (Pali: ), also Maitreya Buddha or Metteyya Buddha, is regarded as the future Buddha of this world in Buddhist eschatology. As the 5th and final Buddha of the current kalpa, Maitreya's teachings will be aimed a ...

.

[Ebrey, et al., ''East Asia'', 270.] Zhu Yuanzhang was a penniless peasant and Buddhist monk who joined the Red Turbans in 1352, but soon gained a reputation after marrying the foster daughter of a rebel commander.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 190] In 1356 Zhu's rebel force captured the city of

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

,

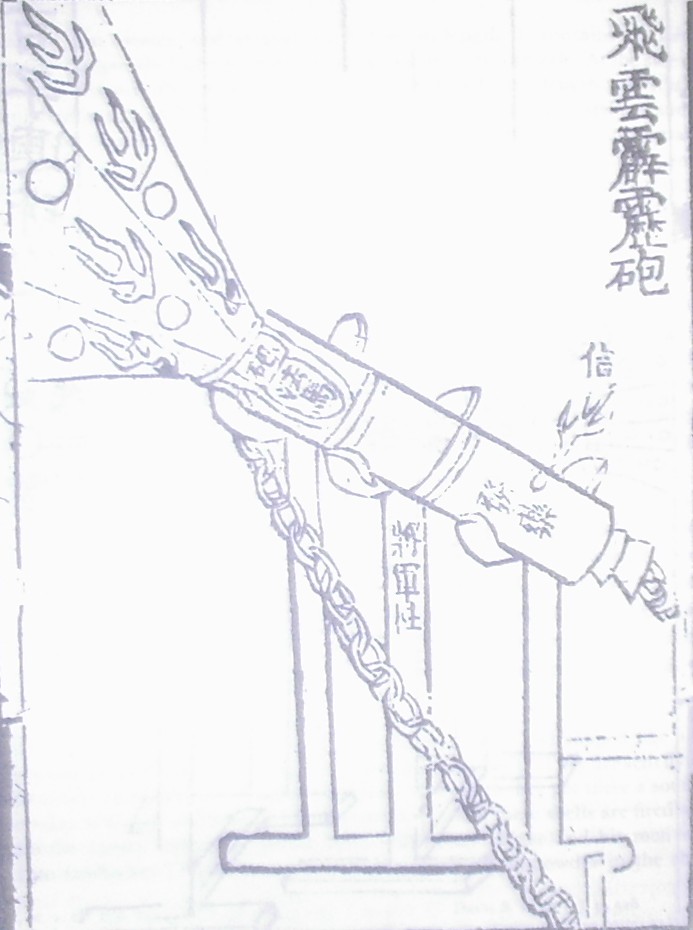

[Gascoigne 151.] which he would later establish as the capital of the Ming dynasty. Zhu enlisted the aid of many able advisors, including the artillery specialists

Jiao Yu

Jiao Yu () was a Chinese military general, philosopher, and writer of the Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty under Zhu Yuanzhang, who founded the dynasty and became known as the Hongwu Emperor. He was entrusted by Zhu as a leading artillery ...

and

Liu Bowen

Liu Ji (1 July 1311 – 16 May 1375),Jiang, Yonglin. Jiang Yonglin. 005(2005). The Great Ming Code: 大明律. University of Washington Press. , 9780295984490. Page xxxv. The source is used to cover the year only. courtesy name Bowen, better kn ...

.

Zhu cemented his power in the south by eliminating his arch rival and rebel leader

Chen Youliang

Chen Youliang (陳友諒; 1320 – 3 October 1363For those cross-referencing the Mingshi, in the old Chinese calendar 至正二十三年 refers to the year 1363 CE, 七月二十日 refers to 8月29日 or 29 August, and 八月二十六日 r ...

in the

Battle of Lake Poyang

The Battle of Lake Poyang () was a naval conflict which took place (30 August – 4 October 1363) between the rebel forces of Zhu Yuanzhang and Chen Youliang during the Red Turban Rebellion which led to the fall of the Yuan dynasty. Chen Youlia ...

in 1363. This battle was—in terms of personnel—one of the

largest naval battles in history. After the dynastic head of the Red Turbans suspiciously died in 1367 while hosted as a guest of Zhu, the latter made his imperial ambitions known by sending an army toward the Yuan capital in 1368.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 191.] The last Yuan emperor fled north into Mongolia and Zhu declared the founding of the Ming dynasty after razing the Yuan palaces in

Dadu (present-day

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

) to the ground.

Instead of the traditional way of naming a dynasty after the first ruler's home district, Zhu Yuanzhang's choice of 'Ming' or 'Brilliant' for his dynasty followed a Mongol precedent of an uplifting title.

Zhu Yuanzhang also took '

Hongwu

Hongwu () (23 January 1368 – 5 February 1399) was the era name of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dynasty of China. Hongwu was also the Ming dynasty's first era name.

Comparison table

Other eras contemporaneous with Hongwu

* ...

', or 'Vastly Martial' as his

reign title. Although the White Lotus had fomented his rise to power, the emperor later denied that he had ever been a member of their organization and suppressed the religious movement after he became emperor.

[Wakeman, 207.]

Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the Ming dynasty, drew on both past institutions and new approaches in order to create 'jiaohua' (meaning 'civilization') as an organic Chinese governing process. This included a building of schools at all levels and an increased study of the classics as well as books on morality. Also included was the distribution of Neo-Confucian ritual manuals and a new civil service examination system for recruitment into the bureaucracy.

Reign of the Hongwu Emperor

The Hongwu Emperor immediately set to rebuilding state infrastructure. He built a long

wall around Nanjing, as well as new palaces and government halls.

The ''

Ming Shi

The ''History of Ming'' or the ''Ming History'' (''Míng Shǐ'') is one of the official Chinese historical works known as the ''Twenty-Four Histories''. It consists of 332 volumes and covers the history of the Ming dynasty from 1368 to 1644. It ...

'' states that as early as 1364 Zhu Yuanzhang had begun drafting a new

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

law code known as the ''Daming Lu'', which was completed by 1397 and repeated certain clauses found in the old

Tang Code

The ''Tang Code'' () was a penal code that was established and used during the Tang Dynasty in China. Supplemented by civil statutes and regulations, it became the basis for later dynastic codes not only in China but elsewhere in East Asia. The Cod ...

of 653.

[Andrew & Rapp, 25.] The Hongwu Emperor organized a military system known as the ''weisuo'', which was similar to the

''fubing'' system of the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618–907). The goal was to have soldiers become self-reliant farmers in order to sustain themselves while not fighting or training.

[Fairbank, 129.] This system was also similar to the Yuan dynasty military organization of a hereditary caste of soldiers and a hereditary nobility of commanders.

The system of the self-sufficient agricultural soldier, however, was largely a farce; infrequent rations and awards were not enough to sustain the troops, and many deserted their ranks if they weren't located in the heavily supplied frontier.

Although a Confucian, the Hongwu Emperor had a deep distrust for the

scholar-officials

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

of the

gentry class and was not afraid to have them beaten in court for offenses.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 191–192.] In favor of Confucian learning and the civil service, the emperor ordered every

county magistrate

County magistrate ( or ) sometimes called local magistrate, in imperial China was the official in charge of the '' xian'', or county, the lowest level of central government. The magistrate was the official who had face-to-face relations with t ...

to open a Confucian school in 1369—following the tradition of a nationwide school system first established by

Emperor Ping of Han (9 BC–5 AD). However, he halted the

civil service examinations in 1373 after complaining that the 120 scholar-officials who obtained a ''jinshi'' degree were incompetent ministers.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 192.][Hucker, 13.] After the examinations were reinstated in 1384,

he had the chief examiner executed after it was discovered that he allowed only candidates from the south to be granted ''jinshi'' degrees.

In 1380, the Hongwu Emperor had the Chancellor

Hu Weiyong

Hu Weiyong (; died 1380) was a Chinese politician and the last chancellor of the Ming dynasty, from 1373 to 1380. Hu was a main member of Huaixi meritorious group. He was later accused of attempting to rebel and was thus executed by the Hongwu Em ...

executed upon suspicion of a conspiracy plot to overthrow him; after that the emperor abolished the

Chancellery and assumed this role as chief executive and emperor.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 192] With a growing amount of suspicion for his ministers and subjects, the Hongwu Emperor established the

Jinyiwei

The Embroidered Uniform Guard () was the imperial secret police that served the emperors of the Ming dynasty in China. The guard was founded by the Hongwu Emperor in 1368 to serve as his personal bodyguards. In 1369 it became an imperial mil ...

, a network of

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

drawn from his own palace guard. They were partly responsible for the loss of 100,000 lives in several major purges over three decades of his rule.

North-Western Frontier

Multiple conflicts arose with the Ming dynasty fighting against the Uyghur Kingdom of Turpan and Oirat Mongols on the Northwestern Border, near

Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

,

Turpan

Turpan (also known as Turfan or Tulufan, , ug, تۇرپان) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 632,000 (2015).

Geonyms

The original name of the cit ...

, and

Hami

Hami (Kumul) is a prefecture-level city in Eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known as the home of sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city was merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city with t ...

. The Ming dynasty took control of Hami (under a small kingdom called

Qara Del) in 1404 and turned it into Hami Prefecture In 1406, the Ming dynasty defeated the ruler of Turpan., which would lead to a lengthy war. The Moghul ruler of Turpan

Yunus Khan

Yunus Khan (b. 1416 – d. 1487) ( ug, يونس خان}), was Khan of Moghulistan from 1462 until his death in 1487. He is identified by many historians with Ḥājjī `Ali (, Pinyin: ''Hazhi Ali'') ( ug, ھاجى علي}), of the contempor ...

, also known as Ḥājjī `Ali (ruled 1462–78), unified

Moghulistan

Moghulistan (from fa, , ''Moghulestân'', mn, Моголистан), also called the Moghul Khanate or the Eastern Chagatai Khanate (), was a Mongol breakaway khanate of the Chagatai Khanate and a historical geographic area north of the Ten ...

(roughly corresponding to today's Eastern

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

) under his authority in 1472. Asserting his newfound power, Ḥājjī `Ali sought redress of old grievances between the Turpanians and Ming China began over the restrictive

tributary trade system. Tensions rose, and in 1473 he led a campaign east to confront China, even succeeding in capturing

Hami

Hami (Kumul) is a prefecture-level city in Eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known as the home of sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city was merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city with t ...

from the Oirat Mongol ruler Henshen. Ali traded control of Hami with the Ming, then Henshen's Mongols, in numerous battles spanning the reigns of his son Ahmed and his grandson Mansur

in a drawn-out and complex series of conflicts now known as the

Ming–Turpan conflict.

South-Western Frontier

In 1381, the Ming dynasty annexed the areas of the southwest that had once been part of the

Kingdom of Dali

The Dali Kingdom, also known as the Dali State (; Bai: Dablit Guaif), was a state situated in modern Yunnan province, China from 937 until 1253. In 1253, it was conquered by the Mongols but members of its former ruling dynasty continued to a ...

, which was annihilated by the Mongols in the 1250s and became established as the Yunnan Province under

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

later on. By the end of the 14th century, some 200,000 military colonists settled some 2,000,000 ''mu'' (350,000 acres) of land in what is now

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

and

Guizhou

Guizhou (; Postal romanization, formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in the Southwest China, southwest region of the China, People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the pr ...

.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 195.] Roughly half a million more Chinese settlers came in later periods; these migrations caused a major shift in the ethnic make-up of the region, since more than half of the roughly 3,000,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the Ming dynasty were non-Han peoples.

In this region, the Ming government adopted a policy of dual administration. Areas with majority ethnic Chinese were governed according to Ming laws and policies; areas where native tribal groups dominated had their own set of laws while tribal chiefs promised to maintain order and send tribute to the Ming court in return for needed goods.

From 1464 to 1466, the

Miao Miao may refer to:

* Miao people, linguistically and culturally related group of people, recognized as such by the government of the People's Republic of China

* Miao script or Pollard script, writing system used for Miao languages

* Miao (Unicode ...

and

Yao people

The Yao people (its majority branch is also known as Mien; ; vi, người Dao) is a government classification for various minorities in China and Vietnam. They are one of the 55 officially recognised ethnic minorities in China and reside in t ...

of

Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

,

Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

,

Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

,

Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

, and Guizhou revolted against what they saw as oppressive government rule; in response, the Ming government sent an army of 30,000 troops (including 1,000 Mongols) to join the 160,000 local troops of Guangxi and crushed the rebellion.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 197.] After the scholar and philosopher

Wang Yangming

Wang Shouren (, 26 October 1472 – 9 January 1529), courtesy name Bo'an (), art name Yangmingzi (), usually referred to as Wang Yangming (), was a Chinese calligrapher, general, philosopher, politician, and writer during the Ming dynasty ...

(1472–1529) suppressed another rebellion in the region, he advocated joint administration of Chinese and local ethnic groups in order to bring about

sinification

Sinicization, sinofication, sinification, or sinonization (from the prefix , 'Chinese, relating to China') is the process by which non-Chinese societies come under the influence of Chinese culture, particularly the language, societal norms, cul ...

in the local peoples' culture.

Relations with Tibet

The ''

Mingshi

The ''History of Ming'' or the ''Ming History'' (''Míng Shǐ'') is one of the official Chinese historical works known as the ''Twenty-Four Histories''. It consists of 332 volumes and covers the history of the Ming dynasty from 1368 to 1644. It ...

''— the official history of the Ming dynasty compiled later by the Qing court in 1739—states that the Ming established itinerant commanderies overseeing Tibetan administration while also renewing titles of ex-Yuan dynasty officials from

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

and conferring new princely titles on leaders of

Tibet's Buddhist sects.

['']Mingshi

The ''History of Ming'' or the ''Ming History'' (''Míng Shǐ'') is one of the official Chinese historical works known as the ''Twenty-Four Histories''. It consists of 332 volumes and covers the history of the Ming dynasty from 1368 to 1644. It ...

''-Geography I "明史•地理一": 東起朝鮮,西據吐番,南包安南,北距大磧。; Geography III "明史•地理三": 七年七月置西安行都衛於此,領河州、朵甘、烏斯藏、三衛。; Western territory III "明史•列傳第二百十七西域三" However,

Turrell V. Wylie states that

censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

in the ''Mingshi'' in favor of bolstering the Ming emperor's prestige and reputation at all costs obfuscates the nuanced history of Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming era.

Modern scholars still debate on whether or not the Ming dynasty really had

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

over Tibet at all, as some believe it was a relationship of loose

suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

which was largely cut off when the

Jiajing Emperor

The Jiajing Emperor (; 16September 150723January 1567) was the 12th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1521 to 1567. Born Zhu Houcong, he was the former Zhengde Emperor's cousin. His father, Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519), Prince of Xing, w ...

(r. 1521–1567) persecuted Buddhism in favor of

Daoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the ''Tao'' ...

at court.

[Wylie, 470.][Wang & Nyima, 1–40.][Laird, 106–107.] Helmut Hoffman states that the Ming upheld the facade of rule over Tibet through periodic missions of "tribute emissaries" to the Ming court and by granting nominal titles to ruling lamas, but did not actually interfere in Tibetan governance.

[Hoffman, 65.] Wang Jiawei and Nyima Gyaincain disagree, stating that Ming China had sovereignty over Tibetans who did not inherit Ming titles, but were forced to travel to Beijing to renew them.

[Wang & Nyima, 37.] Melvyn C. Goldstein writes that the Ming had no real administrative authority over Tibet since the various titles given to Tibetan leaders already in power did not confer authority as earlier Mongol Yuan titles had; according to him, "the Ming emperors merely recognized political reality."

[Goldstein, 4–5.] Some scholars argue that the significant religious nature of the relationship of the Ming court with Tibetan lamas is underrepresented in modern scholarship.

[Norbu, 52.][Kolmas, 32.] Others underscore the commercial aspect of the relationship, noting the Ming dynasty's insufficient number of horses and the need to maintain the

tea-horse trade with Tibet.

[Wang & Nyima, 39–40.][Sperling, 474–475, 478.][Perdue, 273.][Kolmas, 28–29.][Laird, 131] Scholars also debate on how much power and influence—if any—the Ming dynasty court had over the ''de facto'' successive ruling families of Tibet, the Phagmodru (1354–1436), Rinbung (1436–1565), and Tsangpa (1565–1642).

[Kolmas, 29.][Chan, 262.][Norbu, 58.][Wang & Nyima, 42.][Dreyfus, 504.]

The Ming initiated sporadic armed intervention in Tibet during the 14th century, while at times the Tibetans also used successful armed resistance against Ming forays.

[Langlois, 139 & 161.][Geiss, 417–418.] Patricia Ebrey,

Thomas Laird

Thomas C. Laird (born June 30, 1953) is an American journalist, writer, and photographer who specializes in Tibet.

Laird divides his time between New Orleans and Kathmandu, Nepal, where he lived for 30 years. He has photographed and written for ...

, Wang Jiawei, and Nyima Gyaincain all point out that the Ming dynasty did not garrison permanent troops in Tibet,

[Laird, 137.][Ebrey (1999), 227.][Wang & Nyima, 38.] unlike the former Mongol Yuan dynasty.

The

Wanli Emperor

The Wanli Emperor (; 4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun (), was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was th ...

(r. 1572–1620) made attempts to reestablish Sino-Tibetan relations in the wake of a

Mongol-Tibetan alliance initiated in 1578, the latter of which affected the foreign policy of the subsequent Manchu

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

(1644–1912) of China in their support for the

Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

of the

Yellow Hat sect.

[Kolmas, 30–31.][Goldstein, 8.][Laird, 143–144.][The Ming Biographical History Project of the Association for Asian Studies, ''Dictionary of Ming Biography'', 23.] By the late 16th century, the Mongols proved to be successful armed protectors of the Yellow Hat Dalai Lama after their increasing presence in the

Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the bi ...

region, culminating in

Güshi Khan

Güshi Khan (1582 – 14 January 1655; ) was a Khoshut prince and founder of the Khoshut Khanate, who supplanted the Tumed descendants of Altan Khan as the main benefactor of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1637, Güshi ...

's (1582–1655)

conquest of Tibet in 1642.

[Kolmas, 34–35.][Goldstein, 6–9.][Laird, 152.]

The Hongwu Emperor's vision, commercialization, and reversing his policies

Fusion of the merchant and gentry classes

In the first half of the Ming era, scholar-officials would rarely mention the contribution of merchants in society while writing their local

gazetteer

A gazetteer is a geographical index or directory used in conjunction with a map or atlas.Aurousseau, 61. It typically contains information concerning the geographical makeup, social statistics and physical features of a country, region, or con ...

;

[Brook, 73.] officials were certainly capable of funding their own public works projects, a symbol of their virtuous political leadership. However, by the second half of the Ming era it became common for officials to solicit money from merchants in order to fund their various projects, such as building bridges or establishing new schools of Confucian learning for the betterment of the gentry.

[Brook, 90–93.] From that point on the gazetteers began mentioning merchants and often in high esteem, since the wealth produced by their economic activity produced resources for the state as well as increased production of books needed for the education of the gentry. Merchants began taking on the highly cultured, connoisseur's attitude and cultivated traits of the gentry class, blurring the lines between merchant and gentry and paving the way for merchant families to produce scholar-officials. The roots of this social transformation and class indistinction could be

found in the Song dynasty (960–1279), but it became much more pronounced in the Ming. Writings of family instructions for lineage groups in the late Ming period display the fact that one no longer inherited his position in the categorization of the four occupations (in descending order):

gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

,

farmers

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising field crops, orchards, vineyards, poultry, or other livestock. A farmer mig ...

,

artisans

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, ...

, and

merchants

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as industry ...

.

[Brook, 161.]

Courier network and commercial growth

The Hongwu Emperor believed that only government

courier

A courier is a person or organisation that delivers a message, package or letter from one place or person to another place or person. Typically, a courier provides their courier service on a commercial contract basis; however, some couriers are ...

s and lowly retail merchants should have the right to travel far outside their home town.

[Brook, 65–67.] Despite his efforts to impose this view, his building of an efficient communication network for his military and official personnel strengthened and fomented the rise of a potential commercial network running parallel to the courier network. The shipwrecked Korean

Ch'oe Pu (1454–1504) remarked in 1488 how the locals along the eastern coasts of China did not know the exact distances between certain places, which was virtually exclusive knowledge of the Ministry of War and courier agents.

[Brook, 40–43.] This was in stark contrast to the late Ming period, when merchants not only traveled further distances to convey their goods, but also bribed courier officials to use their routes and even had printed geographical guides of commercial routes that imitated the couriers' maps.

An open market, silver, and Deng Maoqi's rebellion

The scholar-officials' dependence upon the economic activities of the merchants became more than a trend when it was semi-institutionalized by the state in the mid Ming era. Qiu Jun (1420–1495), a scholar-official from

Hainan

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slightly l ...

, argued that the state should only mitigate market affairs during times of pending crisis and that merchants were the best gauge in determining the strength of a nation's riches in resources.

[Brook, 102.] The government followed this guideline by the mid Ming era when it allowed merchants to take over the state

monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

of salt production. This was a gradual process where the state supplied northern frontier armies with enough grain by granting merchants licenses to trade in salt in return for their shipping services.

[Brook, 108.] The state realized that merchants could buy salt licenses with silver and in turn boost state revenues to the point where buying grain was not an issue.

Silver mining was increased dramatically during the reign of the

Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

(1402–1424); production of mined silver rose from 3007 kg (80,185 taels) in 1403 to 10,210 kg (272,262 taels) in 1409.

The

Hongxi Emperor

The Hongxi Emperor (16 August 1378 – 29 May 1425), personal name Zhu Gaochi (朱高熾), was the fourth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1424 to 1425. He succeeded his father, the Yongle Emperor, in 1424. His era name "Hongxi" means ...

(r. 1424–1425) attempted to scale back silver mining to restore the discredited

paper currency

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

, but this was a failure which his immediate successor, the

Xuande Emperor

The Xuande Emperor (16 March 1399 31 January 1435), personal name Zhu Zhanji (朱瞻基), was the fifth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1425 to 1435. His era name "Xuande" means "proclamation of virtue". Ruling over a relatively ...

(r. 1425–1435), remedied by continuing the Yongle Emperor's silver mining scheme.

The governments of the Hongwu and

Zhengtong (r. 1435–1449) emperors attempted to cut the flow of silver into the economy in favor of paper currency,

yet mining the precious metal simply became a lucrative illegal pursuit practiced by many.

[Brook, 68–69, 81–83.]

The failure of these stern regulations against silver mining prompted ministers such as the censor Liu Hua (

jinshi

''Jinshi'' () was the highest and final degree in the imperial examination in Imperial China. The examination was usually taken in the imperial capital in the palace, and was also called the Metropolitan Exam. Recipients are sometimes refer ...

graduate in 1430) to support the

''baojia'' system of communal self-defense units to patrol areas and arrest 'mining bandits' (kuangzei).

[Brook 81–82.] Deng Maoqi (died 1449), an overseer in this ''baojia'' defense units in Sha County of

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

, abused local landlords who attempted to have him arrested; Deng responded by killing the local magistrate in 1447 and started a rebellion.

[Brook, 84.] By 1448, Deng's forces took control of several counties and were besieging the

prefectural

A prefecture (from the Latin ''Praefectura'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain international ...

capital.

The mobilization of local ''baojia'' units against Deng was largely a failure; in the end it took 50,000 government troops (including later Mongol rebels who sided with

Cao Qin's rebellion in 1461),

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 99.] with food supplies supported by local wealthy elites, to put down Deng's rebellion and execute the so-called "King Who Eliminates Evil" in the spring of 1449.

Many ministers blamed ministers such as Liu Hua for promoting the ''baojia'' system and thus allowing this disaster to occur.

The historian Tanaka Masatoshi regarded "Deng's uprising as the first peasant rebellion that resisted the class relationship of rent rather than the depredations of officials, and therefore as the first genuinely class-based 'peasant warfare' in Chinese history."

[Brook, 85.]

The Hongwu Emperor was unaware of economic inflation even as he continued to hand out multitudes of banknotes as awards; by 1425, paper currency was worth only 0.025% to 0.014% its original value in the 14th century.

[Fairbank, 134.] The value of standard copper coinage dropped significantly as well due to

counterfeit

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value tha ...

minting; by the 16th century, new maritime trade contacts with Europe provided massive amounts of imported silver, which increasingly became the common

medium of exchange

In economics, a medium of exchange is any item that is widely acceptable in exchange for goods and services. In modern economies, the most commonly used medium of exchange is currency.

The origin of "mediums of exchange" in human societies is ass ...

.

[Fairbank, 134–135.] As far back as 1436, a portion of the southern grain tax was commuted to silver, known as the Gold Floral Silver (''jinhuayin'').

[Brook, xx.] This was an effort to aid tax collection in counties where transportation of grain was made difficult by terrain, as well as provide tax relief to landowners.

[Brook 81.] In 1581 the

Single Whip Reform installed by

Grand Secretary

The Grand Secretariat (; Manchu: ''dorgi yamun'') was nominally a coordinating agency but ''de facto'' the highest institution in the imperial government of the Chinese Ming dynasty. It first took shape after the Hongwu Emperor abolished the o ...

Zhang Juzheng

Zhang Juzheng (; 26 May 1525 – 9 July 1582), courtesy name Shuda (), pseudonym Taiyue (), was a Chinese politician who served as Senior Grand Secretary () in the late Ming dynasty during the reigns of the Longqing and Wanli emperors. He rep ...

(1525–1582) finally assessed taxes on the amount of land paid entirely in silver.

Reign of the Yongle Emperor

Rise to power

The Hongwu Emperor's grandson, Zhu Yunwen, assumed the throne as the

Jianwen Emperor

The Jianwen Emperor (5 December 1377 – ?), personal name Zhu Yunwen (), was the second Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1398 to 1402. The era name of his reign, Jianwen, means "establishing civility" and represented a sharp chan ...

(r. 1398–1402) after the Hongwu Emperor's death in 1398. In a prelude to a three-year-long civil war beginning in 1399,

[Robinson (2000), 527.] The Jianwen Emperor became engaged in a political showdown with his uncle Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan. The emperor was aware of the ambitions of his princely uncles, establishing measures to limit their authority. The militant Zhu Di, given charge over the area encompassing Beijing to watch the Mongols on the frontier, was the most feared of these princes. After the Jianwen Emperor arrested many of Zhu Di's associates, Zhu Di plotted a rebellion. Under the guise of rescuing the young Jianwen Emperor from corrupt officials, Zhu Di personally led forces in the revolt; the palace in Nanjing was burned to the ground, along with the Jianwen Emperor, his wife, mother, and courtiers. Zhu Di assumed the throne as the

Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

(r. 1402–1424); his reign is universally viewed by scholars as a "second founding" of the Ming dynasty since he reversed many of his father's policies.

[Atwell (2002), 84.]

A new capital and a restored canal

The Yongle Emperor demoted Nanjing as a secondary capital and in 1403 announced the new capital of China was to be at his power base in

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

. Construction of a new city there lasted from 1407 to 1420, employing hundreds of thousands of workers daily.

At the center was the political node of the

Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

, and at the center of this was the

Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is a palace complex in Dongcheng District, Beijing, China, at the center of the Imperial City of Beijing. It is surrounded by numerous opulent imperial gardens and temples including the Zhongshan Park, the sacrifi ...

, the palatial residence of the emperor and his family. By 1553, the Outer City was added to the south, which brought the overall size of Beijing to 4 by 4½ miles.

[Ebrey, ''Cambridge Illustrated History of China'', 194.]

After lying dormant and dilapidated for decades, the

Grand Canal was restored under the Yongle Emperor's rule from 1411 to 1415. The impetus for restoring the canal was to solve the perennial problem of

shipping grain north to Beijing. Shipping the annual 4,000,000 ''shi'' (one shi is equal to 107 liters) was made difficult with an inefficient system of shipping grain through the

East China Sea

The East China Sea is an arm of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. It covers an area of roughly . The sea’s northern extension between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula is the Yellow Sea, separated ...

or by several different inland canals that necessitated the transferring of grain onto several different barge types in the process, including shallow and deep-water barges. William Atwell quotes Ming dynasty sources that state the amount of collected tax grain was actually 30 million ''shi'' (93 million

bushel

A bushel (abbreviation: bsh. or bu.) is an imperial and US customary unit of volume based upon an earlier measure of dry capacity. The old bushel is equal to 2 kennings (obsolete), 4 pecks, or 8 dry gallons, and was used mostly for agric ...

s),

[Atwell (2002), 86.] much larger than what Brook notes. The Yongle Emperor commissioned some 165,000 workers to dredge the canal bed in western

Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

and built a series of fifteen

canal lock

A lock is a device used for raising and lowering boats, ships and other watercraft between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber in which the water ...

s.

[Brook, 47.] The reopening of the Grand Canal had implications for Nanjing as well, as it was surpassed by the well-positioned city of

Suzhou

Suzhou (; ; Suzhounese: ''sou¹ tseu¹'' , Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Soochow, is a major city in southern Jiangsu province, East China. Suzhou is the largest city in Jiangsu, and a major economic center and focal point of trad ...

as the paramount commercial center of China.

[Brook, 74–75.] Despite greater efficiency, there were still factors which the government could not control that limited the transportation of taxed grain; for example, in 1420 a widespread crop failure and poor harvest dramatically reduced the tax grain delivered to the central government.

[Atwell (2002), 84, footnote 2.]

Although the Yongle Emperor ordered episodes of bloody purges like his father—including the execution of

Fang Xiaoru

Fang Xiaoru (; 1357–1402), courtesy name Xizhi (希直) or Xigu (希古), was a Chinese politician and Confucian scholar of the Ming dynasty. He was an orthodox Confucian scholar-bureaucrat, famous for his continuation of the Jinhua school of ...

, who refused to draft the proclamation of his succession—the emperor had a different attitude about the scholar-officials.

[Ebrey et al., ''East Asia'', 272.] He had a selection of texts compiled from the

Cheng-

Zhu school of Confucianism—or

Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism (, often shortened to ''lǐxué'' 理學, literally "School of Principle") is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, and originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) ...

—in order to assist those who studied for the civil service examinations.

The Yongle Emperor commissioned two thousand scholars to create a 50-million-word (22,938-chapter) long encyclopedia—the ''

Yongle Encyclopedia

The ''Yongle Encyclopedia'' () or ''Yongle Dadian'' () is a largely-lost Chinese ''leishu'' encyclopedia commissioned by the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1403 and completed by 1408. It comprised 22,937 manuscript rolls or chapters, in 1 ...

''—from seven thousand books.

This surpassed all previous encyclopedias in scope and size, including the 11th-century compilation of the

Four Great Books of Song. Yet the scholar-officials were not the only political group that the Yongle Emperor had to cooperate with and appease. Historian Michael Chang points out that the Yongle Emperor was an "emperor on horseback" who often traversed between two capitals like in the Mongol tradition and constantly led expeditions into Mongolia.

[Chang (2007), 66–67.] This was opposed by the Confucian establishment while it served to bolster the importance of eunuchs and military officers whose power depended upon the emperor's favor.

The treasure fleet

Beginning in 1405, the Yongle Emperor entrusted his favored eunuch commander

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

(1371–1433) as the naval admiral for a gigantic new fleet of ships designated for

international tributary missions. The Chinese had

sent diplomatic missions over land and west since the

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BC–220 AD) and had been engaged in

private overseas trade leading all the way to

East Africa for centuries—culminating in the Song and Yuan dynasties—but no government-sponsored tributary mission of this grandeur size had ever been assembled before. To service seven different tributary missions abroad, the Nanjing shipyards constructed two thousand vessels from 1403 to 1419, which included the large

Chinese treasure ship

A Chinese treasure ship (, literally "gem ship") is a type of large wooden ship in the fleet of admiral Zheng He, who led seven voyages during the early 15th-century Ming dynasty. The size of Chinese treasure ship has been a subject of debate ...

s that measured 112 m (370 ft) to 134 m (440 ft) in length and 45 m (150 ft) to 54 m (180 ft) in width.

[Fairbank, 137.] The first voyage from 1405 to 1407 contained 317 vessels with a staff of 70 eunuchs, 180 medical personnel, 5 astrologers, and 300 military officers commanding a total estimated force of 26,800 men.

The enormous tributary missions were discontinued after the death of Zheng He, yet his death was only one of many culminating factors which brought the missions to an end. The Ming Empire had

conquered and

annexed Vietnam in 1407, but Ming troops were pushed out in 1428 with significant costs to the Ming treasury; in 1431 the new

Lê dynasty

The Lê dynasty, also known as Later Lê dynasty ( vi, Hậu Lê triều, chữ Hán: 後黎朝 or vi, nhà Hậu Lê, link=no, chữ Nôm: 茹後黎), was the longest-ruling Vietnamese dynasty, ruling Đại Việt from 1428 to 1789. The Lê ...

of Vietnam was recognized as an independent tribute state.

[Fairbank, 138.] There was also the threat and revival of Mongol power on the northern steppe which drew court attention away from other matters. The Yongle Emperor had staged enormous invasions deep into Mongol territory, competing with Korea for lands in

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

as well.

To face the Mongol threat to the north, a massive amount of funds were used to build the

Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against Eurasian noma ...

after 1474.

[Fairbank, 139.] The Yongle Emperor's moving of the capital from Nanjing to Beijing was largely in response to the court's need of keeping a closer eye on the Mongol threat in the north. Scholar-officials also associated the lavish expense of the fleets with eunuch power at court, and so halted funding for these ventures as a means to curtail further eunuch influence.

The Tumu Crisis and the Ming Mongols

Succession crisis

The

Oirat leader

Esen Taishi

Esen ( mn, Эсэн; Mongol script: ; ), (?–1454) was a powerful Oirat taishi and the ''de facto'' ruler of the Northern Yuan dynasty between 12 September 1453 and 1454. He is best known for capturing the Emperor Yingzong of Ming in 1450 in th ...

launched an invasion into the Ming dynasty in July 1449. The chief eunuch

Wang Zhen encouraged the

Emperor Yingzong of Ming

Emperor Yingzong of Ming (; 29 November 1427 – 23 February 1464), personal name Zhu Qizhen (), was the sixth and eighth Emperor of the Ming dynasty. He ascended the throne as the Zhengtong Emperor () in 1435, but was forced to abdicate in ...

(r. 1435–1449) to personally lead a force to face the Mongols after a recent Ming defeat; marching off with 50,000 troops, the emperor left the capital and put his half-brother

Zhu Qiyu

The Jingtai Emperor (21 September 1428 – 14 March 1457), born Zhu Qiyu, was the seventh Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1449 to 1457. The second son of the Xuande Emperor, he was selected in 1449 to succeed his elder brother Emper ...

in charge of affairs as temporary regent. In the battle that ensued, his force of 50,000 troops were decimated by Esen's army. On 3 September 1449, the Emperor Yingzong of Ming was captured and held in captivity by the Mongols—an event known as the

Tumu Crisis.

[Ebrey et al., ''East Asia''. 273.] After the Emperor Yingzong of Ming's capture, Esen's forces plundered their way across the countryside and all the way to the suburbs of Beijing. Following this was another plundering of the Beijing suburbs in November of that year by local bandits and Ming dynasty soldiers of Mongol descent who dressed as invading Mongols. Many Han Chinese also took to brigandage soon after the Tumu incident.

The Mongols held the Emperor Yingzong of Ming for ransom. However, this scheme was foiled once the emperor's younger brother assumed the throne as the

Jingtai Emperor (r. 1449–1457); the Mongols were also repelled once the Jingtai Emperor's confidant and defense minister

Yu Qian (1398–1457) gained control of the Ming armed forces. Holding the Emperor Yingzong of Ming in captivity was a useless bargaining chip by the Mongols as long as another sat on his throne, so they released him back into the Ming dynasty.

The Zhengtong Emperor was placed under house arrest in the palace until the coup against the Jingtai Emperor in 1457, which is known as the Duomen Coup ("Wresting the Gate Incident").

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China", 83.] The Emperor Yingzong of Ming retook the throne (r. 1457–1464).

Relocation, migration, and northern raids

The Mongol threat to the Ming dynasty was at its greatest level in the 15th century, although periodic raiding continued throughout the dynasty. Like in the Tumu Crisis, the Mongol leader

Altan Khan

Altan Khan of the Tümed (1507–1582; mn, ᠠᠯᠲᠠᠨ ᠬᠠᠨ, Алтан хан; Chinese: 阿勒坦汗), whose given name was Anda ( Mongolian: ; Chinese: 俺答), was the leader of the Tümed Mongols and de facto ruler of the Right Win ...

(r. 1470–1582) invaded the Ming dynasty and raided as far as the outskirts of Beijing.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China", 81.] The Ming employed troops of Mongol descent to fight back Altan Khan's invasion, as well as Mongol military officers against Cao Qin's abortive coup of 1461. Mongol troops were also employed in the suppression of the

Li people

The Hlai, also known as Li or Lizu, are a Kra–Dai-speaking ethnic group, one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. The vast majority live off the southern coast of China on Hainan Island, where the ...

of

Hainan

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slightly l ...

in the early 16th century as well as the Liu Brothers and Tiger Yang in a 1510 rebellion.

The Mongol incursions prompted the Ming authorities to construct the Great Wall from the late 15th century to the 16th century; John Fairbank notes that "it proved to be a futile military gesture but vividly expressed China's siege mentality."

Yet the Great Wall was not meant to be a purely defensive fortification; its towers functioned rather as a series of lit beacons and signalling stations to allow rapid warning to friendly units of advancing enemy troops.

The Emperor Yingzong of Ming's second reign was a troubled one and Mongol forces within the Ming military structure continued to be problematic. Mongols serving the Ming military also became increasingly circumspect as the Ming began to heavily distrust their Mongol subjects after the Tumu Crisis. One method to ensure that Mongols could not band together in significant numbers in the north was a scheme of relocation and sending their troops on military missions to southern China.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 84–86.] In January 1450, two thousand Mongol troops stationed in Nanjing were sent to

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

in order to suppress a brigand army.

The grand coordinator of

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

, Yang Ning (1400–1458), suggested to the Jingtai Emperor that these Mongols be dispersed amongst the local battalions, a proposal that the emperor agreed to (the exact number of Mongols resettled in this fashion is unknown).

[Robinson, ''Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China'', 87–88.] Despite this, Mongols continued to migrate to Beijing. A massive drought in August 1457 forced over five hundred Mongol families living on the steppe to seek refuge in Ming territories, entering through the Piantou Pass of northwestern

Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-leve ...

.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China", 95.] According to the official report by the chief military officer of Piantou Pass, all of these Mongol families populated Beijing, where they were granted lodging and stipends.

In July 1461, after Mongols had staged raids in June into Ming territory along the northern tracts of the Yellow River, the Minister of War Ma Ang (1399–1476) and General Sun Tang (died 1471) were appointed to lead a force of 15,000 troops to bolster the defenses of

Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 95–96.] Historian David M. Robinson states that "these developments must also have fed suspicion about Mongols living in North China, which in turn exacerbated Mongol feelings of insecurity. However, no direct link can be found between the decision by the Ming Mongols in Beijing to join the

461

__NOTOC__

Year 461 ( CDLXI) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Severinus and Dagalaiphus (or, less frequently, year 1214 ...

coup and activities of steppe Mongols in the northwest."

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 96.]

The failed coup of 1461

On 7 August 1461, the Chinese general Cao Qin (died 1461) and his Ming troops of Mongol descent staged a coup against the Emperor Yingzong of Ming out of fear of being next on his purge-list of those who aided him in the Wresting the Gate Incident. On the previous day, the emperor issued an edict telling his nobles and generals to be loyal to the throne; this was in effect a veiled threat to Cao Qin, after the latter had his associate in the Jinyiwei beaten to death to cover up crimes of illegal foreign transactions.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 97.] Due to the earlier demise of General Shi Heng in 1459, in a similar warning involving an imperial edict, Cao Qin was to take no chances in allowing himself to be ruined in similar fashion.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 97–98.] The loyalty of Cao's Mongol-officer clients was secure due to circumstances of thousands of military officers who had to accept demotions in 1457 because of earlier promotions in aiding the Jingtai Emperor's succession.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 100.] Robinson states that "Mongol officers no doubt expected that if Cao fell from power, they would soon follow."

Cao either planned to kill Ma Ang and Sun Tang as they were to depart the capital with 15,000 troops to Shaanxi on the morning of 7 August, or he simply planned to take advantage of their leave.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 98–99.] The conspirators are said to have planned to place their heir apparent on the throne and demote the Tianshun Emperor's position to "grand senior emperor", the title granted to him during the years of his house arrest.

After a failed plot to have Grand Secretary Li Xian send a

memorial to the throne

A memorial to the throne () was an official communication to the Emperor of China. They were generally careful essays in Classical Chinese and their presentation was a formal affair directed by government officials. Submission of a memorial was a ...

to pardon Cao Qin for killing Lu Gao, head of the Jinyiwei who had been investigating him, Cao Qin began the assault on Dongan Gate, East Chang'an Gate, and West Chang'an Gate, setting fire to the western and eastern gates; these fires were extinguished later in the day by pouring rain.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 104–105.] Ming troops poured into the area outside the

Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

to counterattack.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force, and Ethnicity in Ming China," 106–107.] By midday, Sun Tang's forces had killed two of Cao Qin's brothers and severely wounded Cao in both his arms; his forces took up position in the Great Eastern Market and Lantern Market northeast of Dongan Gate, while Sun deployed artillery units against the rebels.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 107.] Cao lost his third brother, Cao Duo, while attempting to flee out of Beijing by the Chaoyang Gate.

[Robinson, "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China," 108.] Cao fled with his remaining forces to fortify his residential compound in Beijing; Ming troops stormed the residence and Cao Qin committed suicide by throwing himself down a well.

As promised by Li Xian before they stormed the residence, imperial troops were allowed to confiscate the property of Cao Qin for themselves.

Isolation to globalization

Ming rulers faced the challenge of balancing Central Asian trade and military threats against dangerous but profitable sea powers. The questions were cultural, political, and economic. The historian

Arthur Waldron

Arthur Waldron (born December 13, 1948) is an American historian. Since 1997, Waldron has been the Lauder Professor of International Relations in the department of history at the University of Pennsylvania. He works chiefly on Asia, China in parti ...

declares that the early rulers faced the question "Was the Ming to be essentially a Chinese version of the Yuan, or was it to be something new?" The Tang dynasty provided an example of cosmopolitan and culturally flexible rule, but the Song dynasty, which never controlled key areas of Central Asia, offered an example that was culturally Han Chinese. The dynasty was basically reshaped by it successes and frustrations in dealing with the two sides of the outside world.

Universal rulership

The early Ming emperors from the Hongwu Emperor to the

Zhengde Emperor

The Zhengde Emperor (; 26 October 149120 April 1521) was the 11th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1505 to 1521.

Born Zhu Houzhao, he was the Hongzhi Emperor's eldest son. Zhu Houzhao took the throne at only 14 with the era name Z ...

continued Yuan practices such as hereditary military institutions, demanding Korean and Muslim concubines and eunuchs, having Mongols serve in the Ming military, patronizing Tibetan Buddhism, with the early Ming Emperors seeking to project themselves as "universal rulers" to various peoples such as Central Asian Muslims, Tibetans, and Mongols. The Yongle Emperor cited

Emperor Taizong of Tang

Emperor Taizong of Tang (28January 59810July 649), previously Prince of Qin, personal name Li Shimin, was the second emperor of the Tang dynasty of China, ruling from 626 to 649. He is traditionally regarded as a co-founder of the dynasty ...

as a model for being familiar with both China and the steppe people. The legacy of the Mongol Khan's as supporters of both Eastern and western religions, ruler ship over the plains and steppes, was claimed by the Ming such as patronizing Islam and using the Chinese, Persian, and Mongol languages in edicts on Islam which were also used by the Yuan to show the Ming were the heirs to this Yuan legacy.

Illegal trade, piracy, and war with Japan

In 1479, the vice president of the Ministry of War burned the court records documenting Zheng He's voyages; it was one of many events signalling China's shift to an inward foreign policy.

[Fairbank, 138.] Shipbuilding laws were implemented that restricted vessels to a small size; the concurrent decline of the Ming navy allowed the growth of piracy along China's coasts.

Japanese pirates—or

wokou

''Wokou'' (; Japanese: ''Wakō''; Korean: 왜구 ''Waegu''), which literally translates to "Japanese pirates" or "dwarf pirates", were pirates who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century to the 16th century. —began staging raids on Chinese ships and coastal communities, although much of the acts of piracy were carried out by native Chinese.

Instead of mounting a counterattack, Ming authorities chose to shut down coastal facilities and starve the pirates out; all foreign trade was to be conducted by the state under the guise of formal tribute missions.

These were known as the

hai jin laws, a strict ban on private maritime activity until its formal abolishment in 1567.

In this period government-managed overseas trade with

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

was carried out exclusively at the seaport of

Ningbo

Ningbo (; Ningbonese: ''gnin² poq⁷'' , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly romanized as Ningpo, is a major sub-provincial city in northeast Zhejiang province, People's Republic of China. It comprises 6 urban districts, 2 sate ...

, trade with the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

exclusively at

Fuzhou

Fuzhou (; , Fuzhounese: Hokchew, ''Hók-ciŭ''), alternately romanized as Foochow, is the capital and one of the largest cities in Fujian province, China. Along with the many counties of Ningde, those of Fuzhou are considered to constitute ...

, and trade with

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

exclusively at

Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

.

Even then the Japanese were only allowed into port once every ten years and were allowed to bring a maximum of three hundred men on two ships; these laws encouraged many Chinese merchants to engage in widespread illegal trade and smuggling.

The low point in relations between Ming China and Japan occurred during the rule of the great Japanese warlord

Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

, who in 1592 announced he was going to conquer China. In two campaigns (now known collectively as the

Imjin War