History of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This articles covers the history of Italy as a monarchy and in the World Wars.

Modern Italy became a nation-state during the Risorgimento on March 17, 1861, when most of the states of the Italian Peninsula and the

Modern Italy became a nation-state during the Risorgimento on March 17, 1861, when most of the states of the Italian Peninsula and the

After unification, Italy's politics favored radical socialism due to a regionally fragmented right, as conservative Prime Minister

After unification, Italy's politics favored radical socialism due to a regionally fragmented right, as conservative Prime Minister

On 5 February 1885, taking advantage of Egypt's conflict with Britain, Italian soldiers landed at Massawa in present-day

On 5 February 1885, taking advantage of Egypt's conflict with Britain, Italian soldiers landed at Massawa in present-day

In 1892,

In 1892,

Politics were in turmoil. The expansion of the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters in 1912 brought in many workers and peasants, with gains for the Socialist and Catholic forces. New interest groups became better organized, with local organizations and influential newspapers, such as the Catholics, the nationalists, the farmers and the sugar growers. Giolitti lost his once-powerful hold on the press. During Giolitti's three-year absence, the Italian liberal establishment weakened with the rise of Italian nationalism. The nationalists were becoming a popular movement with popular leadership figures such as

Politics were in turmoil. The expansion of the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters in 1912 brought in many workers and peasants, with gains for the Socialist and Catholic forces. New interest groups became better organized, with local organizations and influential newspapers, such as the Catholics, the nationalists, the farmers and the sugar growers. Giolitti lost his once-powerful hold on the press. During Giolitti's three-year absence, the Italian liberal establishment weakened with the rise of Italian nationalism. The nationalists were becoming a popular movement with popular leadership figures such as

In 1911, Giolitti's government agreed to sending forces to occupy Libya. Italy declared war on the

In 1911, Giolitti's government agreed to sending forces to occupy Libya. Italy declared war on the  While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party with anti-war revolutionaries led by future-Fascist dictator

While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party with anti-war revolutionaries led by future-Fascist dictator

Italy entered the

Italy entered the

Under the post World War I settlement, Italy received most of the territories promised in the 1915 agreement, except for

Under the post World War I settlement, Italy received most of the territories promised in the 1915 agreement, except for

At the beginning of

At the beginning of

Mussolini planned to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of the UK in the European theatre. The Italians invaded Egypt, British Somaliland and bombed Mandatory Palestine; the British government refused to accept proposals for a peace that would involve accepting Axis victories in Europe; plans for an invasion of the UK did not proceed and the war continued. Italy was defeated in East Africa; Italian advances in North Africa were successful, but the Italians stopped at Sidi Barrani waiting for logistic supplies to catch up. After the German army defeated Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, Mussolini decided to use Albania as a springboard to invade Greece. The Italians launched their attack on October 28, 1940, and at a meeting of the two fascist dictators in

Mussolini planned to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of the UK in the European theatre. The Italians invaded Egypt, British Somaliland and bombed Mandatory Palestine; the British government refused to accept proposals for a peace that would involve accepting Axis victories in Europe; plans for an invasion of the UK did not proceed and the war continued. Italy was defeated in East Africa; Italian advances in North Africa were successful, but the Italians stopped at Sidi Barrani waiting for logistic supplies to catch up. After the German army defeated Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, Mussolini decided to use Albania as a springboard to invade Greece. The Italians launched their attack on October 28, 1940, and at a meeting of the two fascist dictators in  The new government officially continued the war against the Allies, but started secret negotiations with them. Hitler did not trust Badoglio, and moved a large German force into Italy, on the pretext of fighting the Allied invasion. On September 8, 1943 the Badoglio government announced an armistice with the Allies, but did not declare war on Germany, leaving the army without instructions. Badoglio and the royal family fled to the Allied-controlled regions. In the ensuing confusion, most of the Italian army scattered (with some notable exceptions with the Decima MAS in La Spezia, around Rome and in places such as the Greek island of

The new government officially continued the war against the Allies, but started secret negotiations with them. Hitler did not trust Badoglio, and moved a large German force into Italy, on the pretext of fighting the Allied invasion. On September 8, 1943 the Badoglio government announced an armistice with the Allies, but did not declare war on Germany, leaving the army without instructions. Badoglio and the royal family fled to the Allied-controlled regions. In the ensuing confusion, most of the Italian army scattered (with some notable exceptions with the Decima MAS in La Spezia, around Rome and in places such as the Greek island of

General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942

, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16) by deportation of about 25,000 people, mainly Jews, Croats, and Slovenians, to the

(archived by WebCite), written by

''«Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43''

, Mondadori, Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). ''Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo'', L'Ancora del Mediterraneo.

excerpt and text search

* Lyttelton, Adrian. ''Liberal and Fascist Italy: 1900–1945'' (Short Oxford History of Italy) (2002

excerpt and text search

* McCarthy, Patrick ed. ''Italy since 1945'' (2000) * Smith, D. Mack. ''Modern Italy: A Political History'' (1997

online edition

since 1860 * Toniolo, Gianni. ''An Economic History of Liberal Italy, 1850–1918'' (1990) * Vera Zamagni. ''The Economic History of Italy, 1860–1990'' (1993) 413 pp. . {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Italy As A Monarchy And In The World Wars Modern history of Italy Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) 19th century in Italy 20th century in Italy Italy in World War I Italy in World War II ja:イタリア王国 sr:Краљевина Италија

Italian unification (1738–1870)

Modern Italy became a nation-state during the Risorgimento on March 17, 1861, when most of the states of the Italian Peninsula and the

Modern Italy became a nation-state during the Risorgimento on March 17, 1861, when most of the states of the Italian Peninsula and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and al ...

were united under king Victor Emmanuel II

en, Victor Emmanuel Maria Albert Eugene Ferdinand Thomas

, house = Savoy

, father = Charles Albert of Sardinia

, mother = Maria Theresa of Austria

, religion = Roman Catholicism

, image_size = 252px

, succession ...

of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

, hitherto king of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

, a realm that included Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

.

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, pa ...

(July 4, 1807 – June 2, 1882) was an Italian patriot and soldier of the Risorgimento. He personally led many of the military campaigns that brought about the formation of a unified Italy. He has been dubbed the "Hero of the Two Worlds" in tribute to his military expeditions in South America and Europe.

The architect of Italian unification was Count Camillo Benso di Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (, 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as Cavour ( , ), was an Italian politician, businessman, economist and noble, and a leading figure in the movement tow ...

, the Chief Minister of Victor Emmanuel.

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

itself remained for a decade under the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, and became part of the Kingdom of Italy only in 1870, the final date of Italian unification.

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

's defeat brought an end to the French military protection for Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

and on September 20 Italian troops breached Rome's walls at Porta Pia

Porta Pia is a gate in the Aurelian Walls of Rome, Italy. One of Pope Pius IV's civic improvements to the city, it is named after him. Situated at the end of a new street, the Via Pia, it was designed by Michelangelo in replacement for the Por ...

and entered the city. The Italian occupation forced Pius IX to his palace where he declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican until the Lateran Pacts of 1929.

The Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

(State of the Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

) since 1929 has been an independent enclave surrounded by Rome, Italy.

From the unification to the First World War (1870–1914)

From its beginning, the Italian Nationalist Movement had dreamed about Italy joining the modernized World Powers. In the North, extensive industrialization and the building of a modern infrastructure was well underway by the 1890s. Alpine railway lines connected Italy to the French, German and Austrian rail systems. Two south-going coastal lines were also completed. Most of the larger industrial businesses were founded with considerable investment from Germany, Britain, France and others. Subsequently, the Italian state decided to help initiate heavy industry such as car factories, steel works and ship building, adopting a protectionist trade policy from the 1880s onward. Northern Italian agriculture was modernized, as well, bringing larger profits, underpinned by powerful co-operatives. The South, however, did not experience the same kind of development in any of the above-mentioned areas.Liberal period

After unification, Italy's politics favored radical socialism due to a regionally fragmented right, as conservative Prime Minister

After unification, Italy's politics favored radical socialism due to a regionally fragmented right, as conservative Prime Minister Marco Minghetti

Marco Minghetti (18 November 1818 – 10 December 1886) was an Italian economist and statesman.

Biography

Minghetti was born at Bologna, then part of the Papal States.

He signed the petition to the Papal conclave, 1846, urging the elect ...

only held on to power by enacting revolutionary and socialist-leaning policies to appease the opposition, such as the nationalization of railways. In 1876, Minghetti was ousted and replaced by Agostino Depretis

Agostino Depretis (31 January 181329 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a de ...

, a moderate liberal. Depretis began his term as Prime Minister by initiating an experimental political idea called '' Trasformismo'' (transformism). The theory of ''Trasformismo'' was that a cabinet should select a variety of moderates and capable politicians from a non-partisan perspective. In practice, ''trasformismo'' was authoritarian and corrupt; Depretis pressured districts to vote for his candidates if they wished to gain favourable concessions from Depretis when in power. In the 1876 election, only four representatives from the right were elected, allowing the vrag to be dominated by Depretis. Despotic and corrupt actions are believed to be the key means in which Depretis managed to keep support in southern Italy. He put through authoritarian measures, such as banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy and adopting militarist policies. Depretis enacted controversial legislation for the time, such was abolishing arrest for debt, making elementary education free and compulsory while ending compulsory religious teaching in elementary schools.

Crispi

In 1887, Depretis cabinet minister and former Garibaldi republican Francesco Crispi became Prime Minister. Crispi's major concerns during his term of office was protecting Italy from its dangerous neighbourAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. To meet that threat, Crispi worked to build Italy as a great world power through increased military expenditure, expansionism, and trying to win Germany's favor by joining the Triple Alliance, which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882. While helping Italy develop strategically, he continued ''trasformismo'' and was authoritarian, once suggesting the use of martial law to ban opposition parties. Despite being authoritarian, Crispi put through liberal policies such as the Public Health Act of 1888 and establishing tribunals for redress against abuses by the government.

The overwhelming attention paid to foreign policy alienated the agricultural elements, whose power had been in decline since 1873. Both radical and conservative forces in the Italian parliament demanded that the government investigate how to improve agriculture in Italy. The investigation, which started in 1877 and was published eight years later, showed that agriculture was not improving, that landowners were swallowing up revenue from their lands and contributing almost nothing to the development of the land. There was opposition by lower class Italians to the break-up of communal lands that benefited only landlords. Most of the workers on the agricultural lands were not peasants but short-term labourers who at best were employed for one year. Peasants without stable income were forced to live off meager food supplies, disease was spreading rapidly and plagues were reported, including a major cholera epidemic which killed at least 65,000 people.

The Italian government could not deal with the situation effectively due to the mass overspending of the Depretis government that left Italy in huge debt. Italy also suffered economically because of an overproduction of grapes for their vineyards in the 1870s and 1880s when France's vineyard industry was suffering from vine disease caused by insects. Italy during that time prospered as the largest exporter of wine in Europe, but following the recovery of France in 1888, southern Italy was overproducing and had to cut back, which caused unemployment and bankruptcies.

Early colonialism

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Italy attempted to join the Great Powers in acquiring colonies, though it found this difficult due to resistance and unprofitable due to heavy military costs and the lesser economic value of spheres of influence remaining when Italy began to colonize. A number of colonial projects were undertaken by the government. These were done to gain support of Italian nationalists and imperialists, who wanted to rebuild a Roman Empire. Already, there were large Italian communities inAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, and Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

. Italy first attempted to gain colonies by entering a variety of failed negotiations with other world powers to make colonial concessions. Another approach by Italy was to investigate uncolonized, undeveloped lands by sending missionaries to them. The most promising and realistic lands for colonization were parts of Africa. Italian missionaries had already established a foothold at Massawa

Massawa ( ; ti, ምጽዋዕ, məṣṣəwaʿ; gez, ምጽዋ; ar, مصوع; it, Massaua; pt, Maçuá) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahla ...

in the 1830s and had entered deep into Ethiopia.

During the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

by Britain and France in the 1850s, Cavour believed that this presented an opportunity for Italian access to the East and had wanted the Italian merchant marine to take advantage of the Suez Canal's creation. Following Cavour's initiative, a man named Sapeto was given permission by the Rubattino shipping company to use a ship to establish a station in east Africa as a means of creating a route to the east. Sapeto landed at the Bay of Assab

Assab or Aseb (, ) is a port city in the Southern Red Sea Region of Eritrea. It is situated on the west coast of the Red Sea.

Languages spoken in Assab are predominantly Afar, Tigrinya, and Arabic. Assab is known for its large market, beache ...

, a part of modern-day Eritrea in 1869. One year later, the land was purchased from the local Sultan by the Rubattino shipping company acting on the behalf of the Italian government. In 1882, Assab officially became an Italian territory, making it Italy's first colony. Though Tunisia would have been a preferable target because of its close proximity to Italy, the threat of reaction by the French made the attempt too dangerous to pursue. Italy could not afford the threat of war, as its industry was not developed. Assab stood as the start of the small colonial adventures that Italy would initially undertake.

On 5 February 1885, taking advantage of Egypt's conflict with Britain, Italian soldiers landed at Massawa in present-day

On 5 February 1885, taking advantage of Egypt's conflict with Britain, Italian soldiers landed at Massawa in present-day Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopi ...

, shortly after the fall of Egyptian rule in Khartoum. As was key in Italian foreign policy, the British backed Italy's taking of Massawa from the Egyptians as it aided their occupation efforts. In 1888, Italy annexed Massawa by force, allowing it to pursue its creation of the colony of Italian Eritrea.

In 1885, Italy offered Britain military support for the occupation of Egyptian Sudan, but the British decided that they did not need Italian support to crush the remainder of Egypt, as the forces of Sudanese Muslim rebel Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, ...

, called the Mahdist army in Sudan, already had crushed remaining Egyptian forces, and Ethiopia's (then called Abyssinia) intervention in Sudan also aided the British. Italy's earlier intervention in Assab set off tensions with Ethiopia, which had territorial aims on Assab, and Italy's official annexation of Ethiopian-claimed Massawa in 1888 increased tensions further.

In 1889, Ethiopia's Emperor Yohannes IV

''girmāwī'' His Imperial Majesty, spoken= am , ጃንሆይ ''djānhoi''Your Imperial Majesty(lit. "O steemedroyal"), alternative= am , ጌቶቹ ''getochu''Our Lord (familiar)(lit. "Our master" (pl.)) yohanes

Yohannes IV ( Tigrinya: ዮሓ ...

died in battle in Sudan, Menelik II

, spoken = ; ''djānhoi'', lit. ''"O steemedroyal"''

, alternative = ; ''getochu'', lit. ''"Our master"'' (pl.)

Menelik II ( gez, ዳግማዊ ምኒልክ ; horse name Abba Dagnew ( Amharic: አባ ዳኘው ''abba daññäw''); 17 ...

replaced Yohannes as Emperor. Menelik believed he could negotiate with Italy to avoid war and in error allowed Italy's claim to Massawa. Menelik made another serious blunder when he signed an agreement which declared that Ethiopia would work alongside the King of Italy in its dealings with foreign powers, which the Italians interpreted to declare that Ethiopia had in effect made itself a protectorate of Italy.(Barclay (1973), pp. 32.) Menelik opposed the Italian interpretation and the differences between the two states grew.

In October 1889, Menelik met with a Russian officer who was sent to discuss merging the Russian and Abyssinian orthodox churches, but Menelik was more concerned over Italy's massing army in Eritrea. The meeting was used by Menelik to show unity between Ethiopia and Russia against Italian interests in the area.

Russia's own interests in East Africa led Russia's government to send large amounts of modern weaponry to the Ethiopians to hold back an Italian invasion. In response, Britain decided to back the Italians to challenge Russian influence in Africa and declared that all of Ethiopia was within the sphere of Italian interest. On the verge of war, Italian militarism and nationalism reached a peak, with Italians flocking to the Italian army, hoping to take part in the upcoming war.

In 1895, Ethiopia abandoned its agreement to follow Italian foreign policy, and Italy used the renunciation as a reason to invade Ethiopia, with the support of the United Kingdom. The Italian and British army failed on the battlefield of Adowa

Adwa ( ti, ዓድዋ; amh, ዐድዋ; also spelled Aduwa) is a town and separate woreda in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. It is best known as the community closest to the site of the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Ethiopian soldiers defeated Italian ...

, as the Ethiopians were numerical superior and supported by Russia and France with modern weapons; the sheer large numbers of the Ethiopian warriors forced Italy eventually to retreat into Eritrea. Ethiopia would remain independent from Italy and other colonial powers until it was occupied in 1936 but then subsequently liberated after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Giovanni Giolitti

In 1892,

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A p ...

became Prime Minister of Italy for his first term. Though his first government quickly collapsed a year later, Giolitti returned in 1903 to lead Italy's government during a fragmented reign that lasted until 1914. Giolitti had spent his earlier life as a civil servant, and then took positions within the cabinets of Crispi. Giolitti was the first long-term Italian Prime Minister in many years and was so because he mastered the political concept of ''trasformismo'' by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common, and Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas, while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.

On May 5, 1898, workers in Milan organized a strike to demonstrate against the government of Antonio Starrabba di Rudinì, holding it responsible for the general increase of prices and for the famine that was affecting the country. In response infantry, cavalry and artillery were brought into the city and General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris (; 17 March 1831 – 8 April 1924) was an Italian general, especially remembered for his brutal repression of riots in Milan in 1898, known as the Bava Beccaris massacre.

Biography

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris was born in Fossa ...

ordered his troops to fire on demonstrators. According to the government, there were 118 dead and 450 wounded. King Umberto I praised the General and awarded him the medal of '' Grande Ufficiale dell'Ordine Militare dei Savoia''. The decoration exacerbated the Italian population's indignation. On the other hand, Antonio di Rudinì was forced to resign in July 1898.

On 29 July 1900, at Monza, Umberto I was assassinated by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci

Gaetano Bresci (; November 10, 1869May 22, 1901) was an Italian-American anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I of Italy on July 29, 1900. Bresci was the first European regicide not to be executed, as capital punishment in Italy had been a ...

who claimed he had come directly from America to avenge the victims of the repression, and the offense given by the decoration awarded to General Bava Beccaris.

Southern Italy was in terrible shape prior to and during Giolitti's tenure as Prime Minister. Four-fifths of southern Italians were illiterate and the dire situation there ranged from problems of large numbers of absentee landlords to rebellion and even starvation. Corruption was such a large problem that Giolitti himself admitted that there were places "where the law does not operate at all". Natural disasters like earthquakes and landslides were a common source of destruction in southern Italy, often killing hundreds of people in each disaster, and southern Italy's poverty made repair work very difficult to do. Giolitti's small response to the major earthquake in Messina in 1908 was blamed for the high number of deaths which numbered at 50,000 people. The Messina earthquake infuriated southern Italians who claimed that Giolitti favoured the rich north over them. One study released in 1910 examined tax rates in north, central and southern Italy indicated that northern Italy with 48% of the nation's wealth paid 40% of the nation's taxes, while the south with 27% of the nation's wealth paid 32% of the nation's taxes.

Political upheavals

Politics were in turmoil. The expansion of the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters in 1912 brought in many workers and peasants, with gains for the Socialist and Catholic forces. New interest groups became better organized, with local organizations and influential newspapers, such as the Catholics, the nationalists, the farmers and the sugar growers. Giolitti lost his once-powerful hold on the press. During Giolitti's three-year absence, the Italian liberal establishment weakened with the rise of Italian nationalism. The nationalists were becoming a popular movement with popular leadership figures such as

Politics were in turmoil. The expansion of the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters in 1912 brought in many workers and peasants, with gains for the Socialist and Catholic forces. New interest groups became better organized, with local organizations and influential newspapers, such as the Catholics, the nationalists, the farmers and the sugar growers. Giolitti lost his once-powerful hold on the press. During Giolitti's three-year absence, the Italian liberal establishment weakened with the rise of Italian nationalism. The nationalists were becoming a popular movement with popular leadership figures such as Enrico Corradini

Enrico Corradini (20 July 1865 – 10 December 1931) was an Italian novelist, essayist, journalist and nationalist political figure.

Biography

Corradini was born near Montelupo Fiorentino, Tuscany.

A follower of Gabriele D'Annunzio, he founded ...

and the revolutionary Gabriele D'Annunzio. Nationalists began demanding the return of Italian-populated territories in Austria, demanded Croatian-populated Dalmatia, spoke of the need for Italy to expand territorially into Africa, particularly Libya. Giolitti negotiated with the nationalists demands and began planning an invasion of Ottoman Turkish-held Libya.

The Italian Catholic Electoral Union

The Italian Catholic Electoral Union (''Unione Elettorale Cattolica Italiana'', UECI) was a political organization designed to coordinate the participation of Catholic voices in Italian electoral contests. Its founder and leader was the Count Vinc ...

(''Unione elettorale cattolica italiana'') was formed in 1905 to coordinate Catholic voters. It was formed in 1905 after the suppression of the Opera dei Congressi following the encyclical ''Il fermo proposito'' of Pope Pius X. The Union was headed in 1909–16 by Count Ottorino Gentiloni. The Gentiloni pact of 1913 brought many new Catholic voters into politics, where they supported the Liberal party of Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A p ...

. By the terms of the pact, the Union directed Catholic voters to Giolitti supporters who agreed to favor the Church's position on such key issues as funding private Catholic schools, and blocking a law allowing divorce.

However the Socialists divided over Italy's conquest of Libya in 1911–12. Meanwhile, the nationalists grew in power. The Gentiloni pact brought new Catholic support to the Liberals, who were thus moving to more conservative positions. Increasingly the Radicals and Socialists on the Left rejected Giolitti, especially his pro-Catholic policies. In October 1913 he formed a new government with the clericals. Giolitti stepped down and the new government was headed by Antonio Salandra, a right-wing conservative.

Until 1922, Italy was a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

with a parliament; in 1913, the first universal male suffrage election was held. The so-called Statuto Albertino, which Carlo Alberto

Charles Albert (; 2 October 1798 – 28 July 1849) was the King of Sardinia from 27 April 1831 until 23 March 1849. His name is bound up with the first Italian constitution, the Albertine Statute, and with the First Italian War of Independence ...

conceded in 1848 remained unchanged, even if the kings usually abstained from abusing their extremely large powers (for example, senators were not elected but chosen by the king).

Colonial empire

In 1911, Giolitti's government agreed to sending forces to occupy Libya. Italy declared war on the

In 1911, Giolitti's government agreed to sending forces to occupy Libya. Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

which held Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

as a colony. The war ended only a year later, but the occupation resulted in acts of extreme discrimination towards Libyans such as the forced deportation of Libyans to the Tremiti Islands in October 1911 and by 1912, a third of these Libyan refugees had died due to lack of food supplies and shelter from the Italian occupation forces. Italian control of the area was weak, leading to twenty years of conflict with the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

religious order which was the main political and religious authority in the Libyan hinterlands. The invasion of Libya did mark a turn in direction for the opposition to the Italian government, revolutionaries became divided, some adopting nationalist lines, while others retaining socialist lines.(Bosworth (2005), pp. 49.) The annexation of Libya caused nationalists to advocate Italy's domination of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

by occupying Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

as well as the Adriatic coastal region of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

.

While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party with anti-war revolutionaries led by future-Fascist dictator

While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party with anti-war revolutionaries led by future-Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

calling for violence to bring down the government. Giolitti could no longer rely on the dwindling reformist socialist elements and was forced to concede even further to the right, Giolitti dropped all anticlericalism and reached out to clericals which alienated his moderate liberal base leaving him with an unsteady coalition which collapsed in 1914. By the end of his tenure, Italians detested him and the liberal establishment for the fraudulent elections, the divided society, and the failure and corruption of trasformiso organized governments. Giolitti would return as Prime Minister only briefly in 1920, but the era of liberalism was effectively over in Italy.

Italian colonial ventures began with the acquisition of the ports of Asseb in 1869 and Massawa

Massawa ( ; ti, ምጽዋዕ, məṣṣəwaʿ; gez, ምጽዋ; ar, مصوع; it, Massaua; pt, Maçuá) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahla ...

in 1885 in what is now Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopi ...

. These areas were claimed by Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

at the time, and when Ethiopia went into turmoil at the death of Emperor Yohannes IV Italy moved into the northern Ethiopian highlands. However, further expansion was checked by a revival of Ethiopian power under Emperor Menelik II which led to the defeat of Italian forces at the battle of Adua. However, Italy was still able to secure the northern highlands in the Treaty of Wuchale, ending its conflict with Ethiopia until 1935.

Around the same time Italy began to colonize Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

. It avoided the other powers carving out domains in that area but gradually gained the southern Somali coast beginning with the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Sultanate of Majeerteen in 1888 and continuing with gradual acquisitions until 1925 when Chisimayu Region belonging to the British protectorate of Zanzibar was given to Italy.

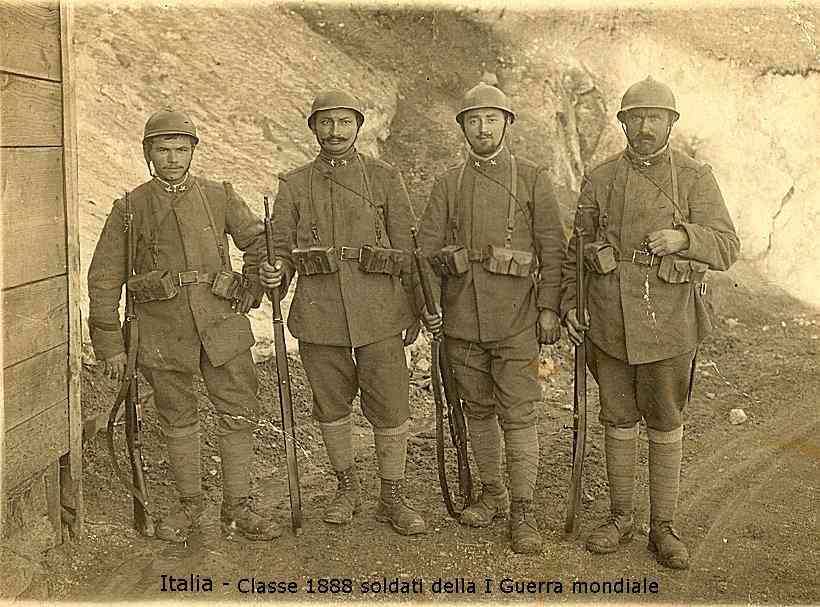

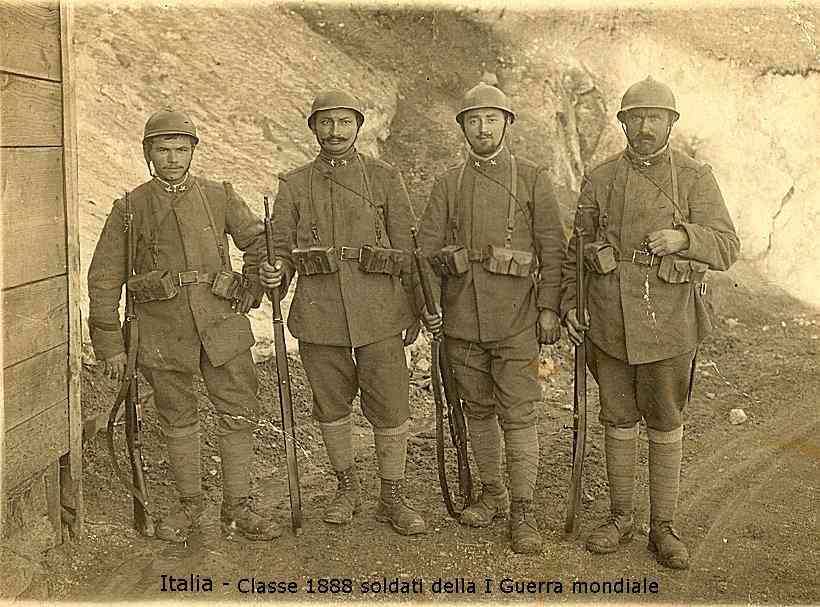

The First World War (1914–1918)

Italy entered the

Italy entered the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence, in a historiographical perspectiv ...

, in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

with the First Italian War of Independence

The First Italian War of Independence ( it, Prima guerra d'indipendenza italiana), part of the Italian Unification (''Risorgimento''), was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other ...

.

At the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Italy remained neutral, claiming that the Triple Alliance had only defensive purposes, and the war was started by the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. However, both the central empires and the Triple Entente tried to attract Italy on their side, and in April 1915 the Italian government agreed ( London Pact) to declare war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire in exchange for several territories (Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

it, Trentino (man) it, Trentina (woman) or it, Altoatesino (man) it, Altoatesina (woman) or it, Sudtirolesegerman: Südtiroler (man)german: Südtirolerin (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title = Official ...

, Province of Trieste

The Province of Trieste ( it, Provincia di Trieste, sl, Tržaška pokrajina; fur, provinzia di Triest) was a province in the autonomous Friuli-Venezia Giulia region of Italy. Its capital was the city of Trieste.

It had an area of and it had a ...

, Istria, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

). In October 1917, the Austrians, having received German reinforcements, broke the Italian lines at Caporetto, but the Italians (helped by their allies) stopped their advance on the river Piave, not far from Venice. After another year of trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artille ...

, and a successful Italian offensive in autumn 1918, the exhausted Austro-Hungarian Empire which was falling apart back home started to negotiate during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. The Austrian-Italian Armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua ended warfare between Italy and Austria-Hungary on the Italian Front during World War I. The armistice was signed on 3 November 1918 in the Villa Giusti, outside Padua in the Veneto, Northern Italy, and ...

was signed on November 3, 1918, but came in effect only a day later. As Austro-Hungarian troops had been prematurely told to stop fighting on the 3rd, the Italians could occupy Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

and capture over 300,000 Austro-Hungarians with hardly any resistance. The Treaty of Saint-Germain confirmed most of the London Pact.

The Fascist regime (1922–1943)

Under the post World War I settlement, Italy received most of the territories promised in the 1915 agreement, except for

Under the post World War I settlement, Italy received most of the territories promised in the 1915 agreement, except for Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, which was mostly given to the newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

. Many Italian workers joined lengthy strikes to demand more rights and better working conditions. Some, inspired by the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, began taking over their factories, mills, farms and workplaces. The liberal establishment, fearing a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

, led by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, whose violent reaction to the strikes (by means of the " Blackshirts" party militia) was often compared to the relatively moderate reactions of the government. After several years of struggle, in October 1922 the fascists attempted a coup (the "Marcia su Roma", i.e. March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 192 ...

); the fascist forces were largely inferior, but the king ordered the army not to intervene, formed an alliance with Mussolini, and convinced the liberal party to endorse a fascist-led government. Over the next few years, Mussolini (who became known as "Il Duce", the leader) eliminated all political parties (including the liberals) and curtailed personal liberties under the pretext of preventing revolution. The nation state could only be formed by means of revolt.

In 1929 Mussolini signed the Lateran Pacts with the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

(with which Italy had been in conflict since the annexation of Rome in 1870), leading to the formation of the tiny independent state of Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

. He was initially on friendly terms with France and Britain, but the situation changed in 1935–36, when Italy invaded the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

despite their opposition (Second Italo-Abyssinian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Ita ...

); because of this and of the ideological affinities with the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

party led by Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. It was a main part of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

with allies being Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

as the ''Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

-Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

-Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

Axis''.

Interwar period

During theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

between the socialist Republicans and Nationalists led by Francisco Franco, Italy sent arms and over 60,000 troops to aid the Nationalist faction.

As Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

annexed Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and moved against Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Italy saw itself becoming a second-rate member of the Axis. The imminent birth of an Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

n royal child meanwhile threatened to give King Zog a lasting dynasty. After Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

invaded Czechoslovakia (March 15, 1939) without notifying Mussolini in advance, the Italian dictator decided to proceed with his own annexation of Albania. Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III criticized the plan to take Albania as an unnecessary risk. On April 7, 1939, Italy invaded Albania; in a short campaign, the country was occupied and joined Italy in personal union.

Italy strengthened its ties with Germany on May 22, 1939, when both nations signed the Pact of Steel. This document solidified the alliance between the two regimes.

Italy and the Second World War (1940–1945)

At the beginning of

At the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

Italy remained neutral (with the consent of Hitler), but it declared war on France and Britain on June 10, 1940, when the French defeat was apparent. Mussolini believed that Britain would beg for peace, and wanted "some casualties in order to get a seat at the peace table", but that proved a huge miscalculation. With the exception of the navy, the Italian armed forces were a major disappointment for Mussolini and Hitler, and German help was constantly needed in Greece and North Africa.

Mussolini planned to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of the UK in the European theatre. The Italians invaded Egypt, British Somaliland and bombed Mandatory Palestine; the British government refused to accept proposals for a peace that would involve accepting Axis victories in Europe; plans for an invasion of the UK did not proceed and the war continued. Italy was defeated in East Africa; Italian advances in North Africa were successful, but the Italians stopped at Sidi Barrani waiting for logistic supplies to catch up. After the German army defeated Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, Mussolini decided to use Albania as a springboard to invade Greece. The Italians launched their attack on October 28, 1940, and at a meeting of the two fascist dictators in

Mussolini planned to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of the UK in the European theatre. The Italians invaded Egypt, British Somaliland and bombed Mandatory Palestine; the British government refused to accept proposals for a peace that would involve accepting Axis victories in Europe; plans for an invasion of the UK did not proceed and the war continued. Italy was defeated in East Africa; Italian advances in North Africa were successful, but the Italians stopped at Sidi Barrani waiting for logistic supplies to catch up. After the German army defeated Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, Mussolini decided to use Albania as a springboard to invade Greece. The Italians launched their attack on October 28, 1940, and at a meeting of the two fascist dictators in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Mussolini stunned Hitler with his announcement of the Italian invasion. Mussolini counted on a quick victory, but the Greek army halted the Italian one in its tracks and soon advanced into Albania. The Greeks took Korçë

Korçë (; sq-definite, Korça) is the eighth most populous city of the Republic of Albania and the seat of Korçë County and Korçë Municipality. The total population is 75,994 (2011 census), in a total area of . It stands on a plateau som ...

and Gjirokastër

Gjirokastër (, sq-definite, Gjirokastra) is a city in the Republic of Albania and the seat of Gjirokastër County and Gjirokastër Municipality. It is located in a valley between the Gjerë mountains and the Drino, at 300 metres above sea ...

, and threatened to drive the Italians from the port city of Vlorë.

Albanian fear of renewed Greek designs on their country prevented effective co-operation with the Greek forces, and Mussolini's forces soon established a stable front in central Albania. Fearful that the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

might become the Achilles heel of her domination of Europe, on April 6, 1941, Germany intervened to crush both Greece and Yugoslavia, and a month later the Axis added Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

to Italian-ruled Albania. Thus Albanian nationalists ironically witnessed the realization of their dreams of uniting most of the Albanian-populated lands during the Axis occupation of their country. With the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and the Balkans, Italy annexed Ljubljana

Ljubljana (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. It is the country's cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the ar ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

, and established the puppet states of Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

and the Hellenic State.

After the invasion of the Soviet Union failed (1941–42), and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

entered the war (December 1941), the situation for the Axis started to deteriorate. In May 1943 the Anglo-Americans completely defeated the Italians and the Germans in North Africa, and in July they landed in Sicily. King Victor Emmanuel III reacted by arresting Mussolini and appointing the army chief of staff, Marshal Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, as Prime Minister.

The new government officially continued the war against the Allies, but started secret negotiations with them. Hitler did not trust Badoglio, and moved a large German force into Italy, on the pretext of fighting the Allied invasion. On September 8, 1943 the Badoglio government announced an armistice with the Allies, but did not declare war on Germany, leaving the army without instructions. Badoglio and the royal family fled to the Allied-controlled regions. In the ensuing confusion, most of the Italian army scattered (with some notable exceptions with the Decima MAS in La Spezia, around Rome and in places such as the Greek island of

The new government officially continued the war against the Allies, but started secret negotiations with them. Hitler did not trust Badoglio, and moved a large German force into Italy, on the pretext of fighting the Allied invasion. On September 8, 1943 the Badoglio government announced an armistice with the Allies, but did not declare war on Germany, leaving the army without instructions. Badoglio and the royal family fled to the Allied-controlled regions. In the ensuing confusion, most of the Italian army scattered (with some notable exceptions with the Decima MAS in La Spezia, around Rome and in places such as the Greek island of Cefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It ...

), and the Germans quickly occupied all of central and northern Italy (the south was already controlled by the Allies). The Germans also liberated Mussolini, who then formed the fascist Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, in the German-controlled areas. This led to the Italian Civil War.

During World War II, Italian war crimes

Italian war crimes have mainly been associated with Fascist Italy in the Pacification of Libya, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II.

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911, Italy went to war with the Ottoman Empire and in ...

included extrajudicial killing

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whethe ...

s and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

James H. Burgwyn (2004)General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942

, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16) by deportation of about 25,000 people, mainly Jews, Croats, and Slovenians, to the

Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The rep ...

, such as Rab

Rab �âːb( dlm, Arba, la, Arba, it, Arbe, german: Arbey) is an island in the northern Dalmatia region in Croatia, located just off the northern Croatian coast in the Adriatic Sea.

The island is long, has an area of and 9,328 inhabitants (2 ...

, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari

Renicci is a village in the municipality of Anghiari, which was the site of a fascist concentration camp for civilians from Yugoslavia, mostly rounded up by Italian troops in Slovenia and in particular in the then Province of Ljubljana.

It is e ...

and elsewhere.

In Italy and Yugoslavia, unlike in Germany, few war crimes were prosecuted.Italy's bloody secret(archived by WebCite), written by

Rory Carroll

Rory Carroll (born 1972) is an Irish journalist working for ''The Guardian'' who has reported from the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, Latin America and Los Angeles. He is the Ireland correspondent for ''The Guardian''. His book on Hugo Chávez, '' ...

, Education, The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

, June 2001 Effie Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 Oliva, Gianni (2006''«Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43''

, Mondadori, Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). ''Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo'', L'Ancora del Mediterraneo.

Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

perpetrated their own crimes against the local ethnic Italian population ( Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) during and after the war, including the foibe massacres

The foibe massacres (; ; ), or simply the foibe, refers to mass killings both during and after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA in the then-Italian territories of Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner an ...

.

While the Allied troops slowly pushed the German resistance to the north (Rome was finally liberated in June 1944 – see Battle of Monte Cassino –, Milan in April 1945) the monarchic government finally declared war on Germany, and an anti-fascist popular resistance movement grew, harassing German forces before the Anglo-American forces drove them out in April 1945.

Aftermath

Much likeJapan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, the aftermath of World War II left Italy with a destroyed economy, a divided society, and anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime for the previous twenty years. These frustrations contributed to a revival of the Italian republican movement. Following Victor Emmanuel III's abdication, his son, the new king Umberto II

en, Albert Nicholas Thomas John Maria of Savoy

, house = Savoy

, father = Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

, mother = Princess Elena of Montenegro

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Racconigi, Piedmont, Kingdom of Italy

, de ...

, was pressured by the threat of another civil war to call a Constitutional Referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

to decide whether Italy should remain a monarchy or become a republic. On 2 June 1946, the republican side won 54% of the vote and Italy officially became a republic. All male members of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

were barred from entering Italy, a ban which was only repealed in 2002.

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Istria, Kvarner, most of the Julian March as well as the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

n city of Zara was annexed by Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 local ethnic Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

( Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), the others being ethnic Slovenians, ethnic Croatians, and ethnic Istro-Romanians, choosing to maintain Italian citizenship. Later, the Free Territory of Trieste was divided between the two states. Italy also lost all of its colonial possessions, formally ending the Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependenci ...

. The Italian border that applies today has existed since 1975, when Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into pr ...

was formally re-annexed to Italy.

See also

*History of Italy as a Republic

The history of the Italian Republic concerns the events relating to the history of Italy that have occurred since 1946, when Italy became a republic. The Italian republican history is generally divided into two phases, the so-called First and Se ...

*House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

(including the list of the modern kings of Italy)

Notes

Further reading

* Bosworth, Richard J. B. ''Mussolini's Italy'' (2005). * Cannistraro, Philip V. ed. ''Historical Dictionary of Fascist Italy'' (1982) * Clark, Martin. ''Modern Italy: 1871–1982'' (1984, 3rd edn 2008) * De Grand, Alexander. ''Giovanni Giolitti and Liberal Italy from the Challenge of Mass Politics to the Rise of Fascism, 1882–1922'' (2001) * De Grand, Alexander. ''Italian Fascism: Its Origins and Development'' (1989) * Ginsborg, Paul. ''A History of Contemporary Italy, 1943–1988'' (2003)excerpt and text search

* Lyttelton, Adrian. ''Liberal and Fascist Italy: 1900–1945'' (Short Oxford History of Italy) (2002

excerpt and text search

* McCarthy, Patrick ed. ''Italy since 1945'' (2000) * Smith, D. Mack. ''Modern Italy: A Political History'' (1997

online edition

since 1860 * Toniolo, Gianni. ''An Economic History of Liberal Italy, 1850–1918'' (1990) * Vera Zamagni. ''The Economic History of Italy, 1860–1990'' (1993) 413 pp. . {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Italy As A Monarchy And In The World Wars Modern history of Italy Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) 19th century in Italy 20th century in Italy Italy in World War I Italy in World War II ja:イタリア王国 sr:Краљевина Италија