History of the Falkland Islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Falkland Islands ( es, Islas Malvinas) goes back at least five hundred years, with active exploration and colonisation only taking place in the 18th century. Nonetheless, the

The history of the Falkland Islands ( es, Islas Malvinas) goes back at least five hundred years, with active exploration and colonisation only taking place in the 18th century. Nonetheless, the

When the world sea level was lower in the

When the world sea level was lower in the

An

An  The name of the archipelago derives from

The name of the archipelago derives from  English Captain John Strong, commander of ''Welfare'', sailed between the two principal islands in 1690 and called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now

English Captain John Strong, commander of ''Welfare'', sailed between the two principal islands in 1690 and called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now

In 1765, Captain John Byron, who was unaware the French had established Port Saint Louis on East Falkland, explored Saunders Island around West Falkland. After discovering a natural harbour, he named the area

In 1765, Captain John Byron, who was unaware the French had established Port Saint Louis on East Falkland, explored Saunders Island around West Falkland. After discovering a natural harbour, he named the area

In March 1820, , a privately owned frigate that was operated as a

In March 1820, , a privately owned frigate that was operated as a

''A Voyage Towards the South Pole''

London, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, 1827 Jewett departed from the Falkland Islands in April 1821. In total he had spent no more than six months on the island, entirely at Port Luis. In 1822, Jewett was accused of piracy by a Portuguese court, but by that time he was in Brazil.

In 1823, the United Provinces of the River Plate granted

In 1823, the United Provinces of the River Plate granted

, Accessed 2007-07-19 On 10 June 1829, Vernet was designated as 'civil and military commandant' of the islands (no governor was ever appointed) and granted a monopoly on seal hunting rights. A protest was lodged by the British Consulate in Buenos Aires. By 1831, the colony was successful enough to be advertising for new colonists, although 's report suggests that the conditions on the islands were quite miserable.

Accessed 2007-10-02

The Argentinian assertions of sovereignty provided the spur for Britain to send a naval task force in order to finally and permanently return to the islands.

On 3 January 1833, Captain James Onslow, of the brig-sloop , arrived at Vernet's settlement at Port Louis to request that the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate be replaced with the British one, and for the administration to leave the islands. While Major José María Pinedo, commander of the schooner ''Sarandí'', wanted to resist, his numerical disadvantage was obvious, particularly as a large number of his crew were British mercenaries who were unwilling to fight their own countrymen. Such a situation was not unusual in the newly independent states in Latin America, where land forces were strong, but navies were frequently quite undermanned. As such he protested verbally, but departed without a fight on 5 January. Argentina claims that Vernet's colony was also expelled at this time, though sources from the time appear to dispute this, suggesting that the colonists were encouraged to remain initially under the authority of Vernet's storekeeper, William Dickson and later his deputy, Matthew Brisbane.

Initial British plans for the Islands were based upon the continuation of Vernet's settlement at Port Louis. An Argentine immigrant of Irish origin, William Dickson, was appointed as the British representative and provided with a flagpole and flag to be flown whenever ships were in harbour. In March 1833, Vernet's Deputy, Matthew Brisbane returned and presented his papers to Captain

The Argentinian assertions of sovereignty provided the spur for Britain to send a naval task force in order to finally and permanently return to the islands.

On 3 January 1833, Captain James Onslow, of the brig-sloop , arrived at Vernet's settlement at Port Louis to request that the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate be replaced with the British one, and for the administration to leave the islands. While Major José María Pinedo, commander of the schooner ''Sarandí'', wanted to resist, his numerical disadvantage was obvious, particularly as a large number of his crew were British mercenaries who were unwilling to fight their own countrymen. Such a situation was not unusual in the newly independent states in Latin America, where land forces were strong, but navies were frequently quite undermanned. As such he protested verbally, but departed without a fight on 5 January. Argentina claims that Vernet's colony was also expelled at this time, though sources from the time appear to dispute this, suggesting that the colonists were encouraged to remain initially under the authority of Vernet's storekeeper, William Dickson and later his deputy, Matthew Brisbane.

Initial British plans for the Islands were based upon the continuation of Vernet's settlement at Port Louis. An Argentine immigrant of Irish origin, William Dickson, was appointed as the British representative and provided with a flagpole and flag to be flown whenever ships were in harbour. In March 1833, Vernet's Deputy, Matthew Brisbane returned and presented his papers to Captain

Immediately following their return to the Falkland Islands and the failure of Vernet's settlement, the British maintained Port Louis as a military outpost. There was no attempt to colonise the islands following the intervention, instead there was a reliance upon the remaining rump of Vernet's settlement. Lt. Smith received little support from the

Immediately following their return to the Falkland Islands and the failure of Vernet's settlement, the British maintained Port Louis as a military outpost. There was no attempt to colonise the islands following the intervention, instead there was a reliance upon the remaining rump of Vernet's settlement. Lt. Smith received little support from the

In 1833 the United Kingdom asserted authority over the Falkland Islands and

In 1833 the United Kingdom asserted authority over the Falkland Islands and  Government House opened as the offices of the Lieutenant Governor in 1847. Government House continued to develop with various additions, formally becoming the Governor's residence in 1859 when Governor Moore took residence. Government House remains the residence of the Governor.

Many of the colonists begin to move from Ansons' Harbour to Port Stanley. As the new town expanded, the population grew rapidly, reaching 200 by 1849. The population was further expanded by the arrival of 30 married

Government House opened as the offices of the Lieutenant Governor in 1847. Government House continued to develop with various additions, formally becoming the Governor's residence in 1859 when Governor Moore took residence. Government House remains the residence of the Governor.

Many of the colonists begin to move from Ansons' Harbour to Port Stanley. As the new town expanded, the population grew rapidly, reaching 200 by 1849. The population was further expanded by the arrival of 30 married

A few years after the British had established themselves in the islands, a number of new British settlements were started. Initially many of these settlements were established in order to exploit the feral cattle on the islands. Following the introduction of the Cheviot breed of sheep to the islands in 1852, sheep farming became the dominant form of agriculture on the Islands.

A few years after the British had established themselves in the islands, a number of new British settlements were started. Initially many of these settlements were established in order to exploit the feral cattle on the islands. Following the introduction of the Cheviot breed of sheep to the islands in 1852, sheep farming became the dominant form of agriculture on the Islands.

Lafone continued to develop his business interests and in 1849 looked to establish a joint stock company with his London creditors. The company was launched as The Royal Falkland Land, Cattle, Seal and Fishery Company in 1850 but soon thereafter was incorporated under

Lafone continued to develop his business interests and in 1849 looked to establish a joint stock company with his London creditors. The company was launched as The Royal Falkland Land, Cattle, Seal and Fishery Company in 1850 but soon thereafter was incorporated under

A canning factory was opened in 1911 at Goose Green and was initially extremely successful. It absorbed a large proportion of surplus sheep but during the postwar slump it suffered a serious loss and closed in 1921.

Despite this setback, a mere year later, the settlement grew after it became the base for the Falkland Islands Company's

A canning factory was opened in 1911 at Goose Green and was initially extremely successful. It absorbed a large proportion of surplus sheep but during the postwar slump it suffered a serious loss and closed in 1921.

Despite this setback, a mere year later, the settlement grew after it became the base for the Falkland Islands Company's  Similarly,

Similarly,

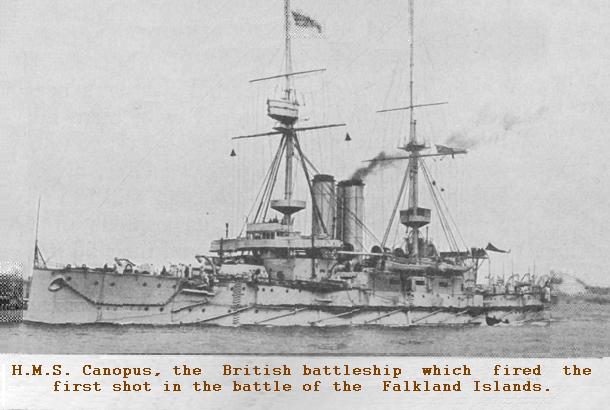

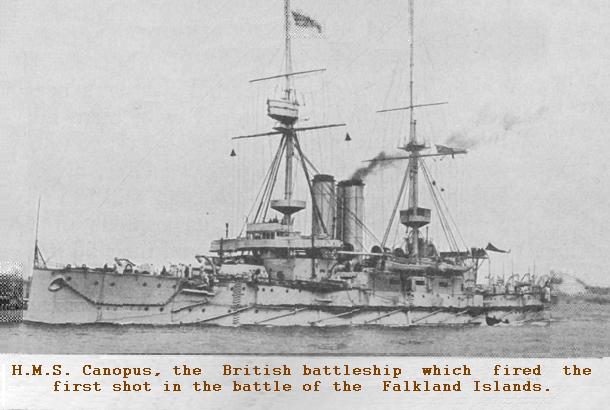

Port Stanley became an important coaling station for the Royal Navy. This led to ships based there being involved in major naval engagements in both the First and Second World Wars.

The strategic significance of the Falkland Islands was confirmed by the second major naval engagement of the First World War. Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee's

Port Stanley became an important coaling station for the Royal Navy. This led to ships based there being involved in major naval engagements in both the First and Second World Wars.

The strategic significance of the Falkland Islands was confirmed by the second major naval engagement of the First World War. Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee's

A more serious incident took place on 28 September 1966 when eighteen young

A more serious incident took place on 28 September 1966 when eighteen young  In November 1968, Miguel Fitzgerald was hired by the Argentine press to attempt a reprise of his 1964 landing. Accompanied by one of the 1966 hijackers, he flew to Stanley but on arrival found he could not land at the racecourse due to obstacles placed following the hijacking. The plane was forced to crash land on Eliza Cove Road, but the two occupants were unharmed. The stunt was intended to coincide with the visit of

In November 1968, Miguel Fitzgerald was hired by the Argentine press to attempt a reprise of his 1964 landing. Accompanied by one of the 1966 hijackers, he flew to Stanley but on arrival found he could not land at the racecourse due to obstacles placed following the hijacking. The plane was forced to crash land on Eliza Cove Road, but the two occupants were unharmed. The stunt was intended to coincide with the visit of

Despite these tensions relationships between the islanders and the Argentines operating the new services in the islands were cordial. Although there was apprehension, politics were generally avoided and on a one-to-one basis there was never any real hostility.

On the international level, relations began to sour in 1975 when Argentine delegates at the London meeting of the

Despite these tensions relationships between the islanders and the Argentines operating the new services in the islands were cordial. Although there was apprehension, politics were generally avoided and on a one-to-one basis there was never any real hostility.

On the international level, relations began to sour in 1975 when Argentine delegates at the London meeting of the

Following the war, Britain focused on improving its facilities on the islands. It increased its military presence significantly, building a large base at

Following the war, Britain focused on improving its facilities on the islands. It increased its military presence significantly, building a large base at

Mount Pleasant, to the west of Stanley, was chosen as the site for the new base. The airfield was opened by

Mount Pleasant, to the west of Stanley, was chosen as the site for the new base. The airfield was opened by

Before the Falklands War, sheep-farming was the Falkland Islands' only industry. Since the late 1980s, when two species of squid popular with consumers were discovered in substantial numbers near the Falklands, fishing has become the largest part of the economy.

On 14 September 2011, Rockhopper Exploration announced plans under way for oil production to commence in 2016, through the use of Floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) technology, replicating the methodology used on the Foinaven field off the Shetland Islands. The production site will require approximately 110 people working offshore and another 40 working onshore. The oil is expected to trade at of the Brent crude price.

Some small businesses attempted at Fox Bay have included a market garden, a salmon farm and a knitting mill with "Warrah Knitwear".

Before the Falklands War, sheep-farming was the Falkland Islands' only industry. Since the late 1980s, when two species of squid popular with consumers were discovered in substantial numbers near the Falklands, fishing has become the largest part of the economy.

On 14 September 2011, Rockhopper Exploration announced plans under way for oil production to commence in 2016, through the use of Floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) technology, replicating the methodology used on the Foinaven field off the Shetland Islands. The production site will require approximately 110 people working offshore and another 40 working onshore. The oil is expected to trade at of the Brent crude price.

Some small businesses attempted at Fox Bay have included a market garden, a salmon farm and a knitting mill with "Warrah Knitwear".

1987 American report

by Richard D. Chenette, Lieutenant Commander, USN, laying out the history and background of the disputed claims

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20071006063014/http://www.falklands.info/history/timeline.html Timeline of Falklands Island history {{DEFAULTSORT:History of the Falkland Islands British colonization of the Americas French colonization of the Americas Spanish colonization of the Americas Falkland Islands in World War II 1600s in the Dutch Empire Maritime history of the Dutch Republic

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

have been a matter of controversy, as they have been claimed by the French, British, Spaniards and Argentines at various points.

The islands were uninhabited when discovered by Europeans. France established a colony on the islands in 1764. In 1765, a British captain claimed the islands for Britain. In early 1770 a Spanish commander arrived from Buenos Aires with five ships and 1,400 soldiers forcing the British to leave Port Egmont. Britain and Spain almost went to war over the islands, but the British government decided that it should withdraw its presence from many overseas settlements in 1774. Spain, which had a garrison at Puerto Soledad

Puerto Soledad (''Puerto de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad'', en, Port Solitude) was a Spanish military outpost and penal colony on the Falkland Islands, situated at an inner cove of Berkeley Sound (french: ,Dom Pernety, Antoine-Joseph. ''Journ ...

on East Falklands, administered the garrison from Montevideo until 1811 when it was compelled to withdraw as a result of the war against Argentine independence and the pressures of Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

. In 1833, the British returned to the Falkland Islands. Argentina invaded the islands on 2 April 1982. The British responded with an expeditionary force that forced the Argentines to surrender.

Claims of pre-Columbian discovery

When the world sea level was lower in the

When the world sea level was lower in the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

, the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

may have been joined to the mainland of South America.

While Fuegian

Fuegians are the indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. In English, the term originally referred to the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego. In Spanish, the term ''fueguino'' can refer to any person fro ...

s from Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

could have visited the Falklands, the islands were uninhabited when discovered by Europeans. Recent discoveries of arrowheads in Lafonia

Lafonia is a peninsula forming the southern part of East Falkland, the largest of the Falkland Islands.

Geography and geology

Shaped like the letter "E", it is joined to the northern part of the island by an isthmus that is almost wide. Were ...

(on the southern half of East Falkland

East Falkland ( es, Isla Soledad) is the largest island of the Falklands in the South Atlantic, having an area of or 54% of the total area of the Falklands. The island consists of two main land masses, of which the more southerly is known as La ...

) as well as the remains of a wooden canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the ter ...

provide evidence that the Yaghan people

The Yahgan (also called Yagán, Yaghan, Yámana, Yamana or Tequenica) are a group of indigenous peoples in the Southern Cone. Their traditional territory includes the islands south of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, extending their presence int ...

of Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

may have made the journey to the islands. It is not known if these are evidence of one-way journeys, but there is no known evidence of pre-Columbian buildings or structures. However, it is not certain that the discovery predates arrival of Europeans. A Patagonian Missionary Society mission station was founded on Keppel Island

Keppel Island ( es, Isla de la Vigia) is one of the Falkland Islands, lying between Saunders and Pebble islands, and near Golding Island to the north of West Falkland on Keppel Sound. It has an area of and its highest point, Mt. Keppel, is ...

(off the west coast of West Falkland

West Falkland ( es, Isla Gran Malvina) is the second largest of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. It is a hilly island, separated from East Falkland by the Falkland Sound. Its area is , 37% of the total area of the islands. Its coastli ...

) in 1856. Yahgan people were at this station from 1856 to 1898 so this may be the source of the artifacts that have been found. In 2021, a paper was published on deposits of marine animal bones (primarily South American sea lion

The South American sea lion (''Otaria flavescens'', formerly ''Otaria byronia''), also called the southern sea lion and the Patagonian sea lion, is a sea lion found on the western and southeastern coasts of South America. It is the only member ...

and Southern rockhopper penguin

The southern rockhopper penguin group (''Eudyptes chrysocome''), is a species of rockhopper penguin, that is sometimes considered distinct from the northern rockhopper penguin. It occurs in subantarctic waters of the western Pacific and Indian ...

) on New Island off the coast of West Falkland, at the same site where a quartzite arrowhead made of local stone had been found in 1979. The sites dated to 1275 to 1420 CE, and were interpreted as processing or midden sites where marine animals had been butchered. A charcoal spike consistent with anthropogenic causes (''i.e.'' caused by humans) on New Island was also dated to 550 BP (1400 CE). The Yaghan people were capable seafarers, and are known to have travelled to the Diego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands ( es, Islas Diego Ramírez) are a small group of subantarctic islands located in the southernmost extreme of Chile.

History

The islands were first sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, ...

around 105 km (65 mi) south of Cape Horn, and were suggested to be responsible for the creation of the mounds.

The past presence of the Falkland Islands wolf, ''Dusicyon australis'', has often been cited as evidence of pre-European occupation of the islands, however this is contested. The animal was observed in the Falklands by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, but is now extinct.

The islands had no native trees when discovered but there is some ambiguous evidence of past forestation, that may be due to wood being transported by oceanic currents from Patagonia. All modern trees have been introduced by Europeans.

European discovery

An

An archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

in the region of the Falkland Islands appeared on Portuguese map

A map is a symbolic depiction emphasizing relationships between elements of some space, such as objects, regions, or themes.

Many maps are static, fixed to paper or some other durable medium, while others are dynamic or interactive. Although ...

s from the early 16th century. Researchers Pepper and Pascoe cite the possibility that an unknown Portuguese expedition may have sighted the islands, based on the existence of a French copy of a Portuguese map from 1516. Maps from this period show islands known as the ''Sanson'' islands in a position that could be interpreted as the Falklands.

Sightings of the islands are attributed to Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

or Estêvão Gomes

Estêvão Gomes, also known by the Spanish version of his name, Esteban Gómez (c. 1483 – 1538), was a Portuguese cartography, cartographer and explorer. He sailed at the service of Crown of Castile, Castile (Spain) in the fleet of Ferdinand M ...

of ''San Antonio'', one of the captains in the expedition, as the Falklands fit the description of those visited to gather supplies. The account given by Antonio Pigafetta

Antonio Pigafetta (; – c. 1531) was an Venetian scholar and explorer. He joined the expedition to the Spice Islands led by explorer Ferdinand Magellan under the flag of the emperor Charles V and after Magellan's death in the Philippine Islands, ...

, the chronicler of Magellan's voyage, contradicts attribution to either Gomes or Magellan, since it describes the position of islands close to the Patagonia coast, with the expedition following the mainland coast and the islands visited between a latitude of 49° and 51°S and also refers to meeting "giants" (described as Sansón or Samsons in the chronicle) who are believed to be the Tehuelche Indians. Although acknowledging that Pigafetta's account casts doubt upon the claim, the Argentine historian Laurio H. Destefani asserts it probable that a ship from the Magellan expedition discovered the islands citing the difficulty in measuring longitude accurately, which means that islands described as close to the coast could be further away. Destefani dismisses attribution to Gomes since the course taken by him on his return would not have taken the ships near the Falklands.

Destefani also attributes an early visit to the Falklands by an unknown Spanish ship, although Destefani's firm conclusions are contradicted by authors who conclude the sightings refer to the Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel (; Yahgan: ''Onašaga'') is a strait in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, on the extreme southern tip of South America between Chile and Argentina. The channel separates the larger main island of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego f ...

.

Lord Falkland

Viscount Falkland is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. Referring to the royal burgh of Falkland in Fife, it was created in 1620, by King James VI, for Sir Henry Cary, who was born in Hertfordshire and had no previous connection to Scotla ...

, the Treasurer of the Admiralty, who organized the first expedition to South Atlantic with the intention to explore the Islands.

When English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

explorer John Davis, commander of , one of the ships belonging to Thomas Cavendish

Sir Thomas Cavendish (1560 – May 1592) was an English explorer and a privateer known as "The Navigator" because he was the first who deliberately tried to emulate Sir Francis Drake and raid the Spanish towns and ships in the Pacific and retu ...

's second expedition to the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

, separated from Cavendish off the coast of what is now southern Argentina, he decided to make for the Strait of Magellan in order to find Cavendish. On 9 August 1592 a severe storm battered his ship, and Davis drifted under bare masts, taking refuge "among certain Isles never before discovered". Davis did not provide the latitude of these islands, indicating they were away from the Patagonian coast (they are actually away). Navigational errors due to the longitude problem

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the longitude of any given place on Earth.

The measurement of longitude is important to both cartography ...

were a common problem until the late 18th century, when accurate marine chronometers became readily available, although Destefani asserts the error here to be "unusually large".

In 1594, they may have been visited by English commander Richard Hawkins

Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins (or Hawkyns) (c. 1562 – 17 April 1622) was a 17th-century English seaman, explorer and privateer. He was the son of Admiral Sir John Hawkins.

Biography

He was from his earlier days familiar with ships and the s ...

with his ship the '' Dainty'', who, combining his own name with that of Queen Elizabeth I, the "Virgin Queen", gave a group of islands the name of "Hawkins' Maidenland". However, the latitude given was off by at least 3 degrees and the description of the shore (including the sighting of bonfires) casts doubts on his discovery. Errors in the latitude measured can be attributed to a simple mistake reading a cross staff

The term Jacob's staff is used to refer to several things, also known as cross-staff, a ballastella, a fore-staff, a ballestilla, or a balestilha. In its most basic form, a Jacob's staff is a stick or pole with length markings; most staffs ar ...

divided into minutes, meaning the latitude measured could have been 50° 48' S. The description of bonfires can also be attributed to peat fires caused by lightning, which is not uncommon in the outer islands of the Falklands in February. In 1925, Conor O'Brian analysed the voyage of Hawkins and concluded that the only land he could have sighted was Steeple Jason Island. The British historian Mary Cawkell also points out that criticism of the account of Hawkins' discovery should be tempered by the fact it was written nine years after the event; Hawkins was captured by the Spanish and spent eight years in prison.

On 24 January 1600, the Dutchman Sebald de Weert

Sebald or Sebalt de Weert (May 2, 1567 – May 30 or June 1603) was a Flemish captain and vice-admiral of the Dutch East India Company (known in Dutch as ''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'', VOC). He is most widely remembered for accurately p ...

visited the Jason Islands

The Jason Islands (Spanish: ''Islas Sebaldes'') are an archipelago in the Falkland Islands, lying to the far north-west of West Falkland. Three of the islands, Steeple Jason, Grand Jason and Clarke's Islet, are private nature reserves owned by ...

and called them the Sebald Islands (in Spanish, "Islas Sebaldinas" or "Sebaldes"). This name remained in use for the entire Falkland Islands for a long time; William Dampier

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651; died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate, privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumnav ...

used the name ''Sibbel de Wards'' in his reports of his visits in 1684 and 1703, while James Cook still referred to the Sebaldine Islands in the 1770s. The latitude that De Weert provided (50° 40') was close enough as to be considered, for the first time beyond doubt, the Falkland Islands.

English Captain John Strong, commander of ''Welfare'', sailed between the two principal islands in 1690 and called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now

English Captain John Strong, commander of ''Welfare'', sailed between the two principal islands in 1690 and called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now Falkland Sound

The Falkland Sound ( es, Estrecho de San Carlos) is a sea strait in the Falkland Islands. Running southwest-northeast, it separates West and East Falkland.

Name

The sound was named by John Strong in 1690 for Viscount Falkland, the name only l ...

), after Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount Falkland (1656–1694), who as Commissioner of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

had financed the expedition and later became First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. From this body of water the island group later took its collective name.

Early colonisation

The French explorerLouis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (, , ; 12 November 1729 – August 1811) was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he took part in the Seven Years' War in North America and the American Revolutio ...

established a colony at Port St. Louis, on East Falkland's Berkeley Sound

Berkeley Sound is an inlet, or fjord in the north east of East Falkland in the Falkland Islands. The inlet was the site of the first attempts at colonisation of the islands, at Port Louis, by the French.

Berkeley Sound has several smaller bays ...

coast in 1764. The French name ''Îles Malouines'' was given to the islands – ''malouin'' being the adjective for the Breton port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

of Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

. The Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

name ''Islas Malvinas'' is a translation of the French name of ''Îles Malouines''.

In 1765, Captain John Byron, who was unaware the French had established Port Saint Louis on East Falkland, explored Saunders Island around West Falkland. After discovering a natural harbour, he named the area

In 1765, Captain John Byron, who was unaware the French had established Port Saint Louis on East Falkland, explored Saunders Island around West Falkland. After discovering a natural harbour, he named the area Port Egmont

Port Egmont (Spanish: ''Puerto de la Cruzada''; French: ''Poil de la Croisade'') was the first British settlement in the Falkland Islands, on Saunders Island off West Falkland, and is named after the Earl of Egmont.

Toponym

The original name ...

and claimed the islands for Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

on the grounds of prior discovery. The next year Captain John MacBride

John MacBride (sometimes written John McBride; ga, Seán Mac Giolla Bhríde; 7 May 1868 – 5 May 1916) was an Irish republican and military leader. He was executed by the British government for his participation in the 1916 Easter R ...

established a permanent British settlement at Port Egmont.

Under the alliance established by the Pacte de Famille, in 1766 France agreed to leave after the Spanish complained about French presence in territories they considered their own. Spain agreed to compensate Louis de Bougainville, the French admiral and explorer who had established the settlement on East Falkland at his own expense. In 1767, the Spanish formally assumed control of Port St. Louis and renamed it ''Puerto Soledad

Puerto Soledad (''Puerto de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad'', en, Port Solitude) was a Spanish military outpost and penal colony on the Falkland Islands, situated at an inner cove of Berkeley Sound (french: ,Dom Pernety, Antoine-Joseph. ''Journ ...

'' (English: Port Solitude).

In early 1770 Spanish commander, Don Juan Ignacio de Madariaga, briefly visited Port Egmont. On 10 June he returned from Argentina with five armed ships and 1400 soldiers forcing the British to leave Port Egmont. This action sparked the Falkland Crisis between 10 July 1770 to 22 January 1771 when Britain and Spain almost went to war over the islands. However, conflict was averted when the colony was re-established by Captain John Stott with the ships , HMS ''Hound'' and HMS ''Florida'' (a mail ship which had already been at the founding of the original settlement). Egmont quickly became an important port-of-call for British ships sailing around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

.

With the growing economic pressures stemming from the upcoming American War of Independence, the British government decided that it should withdraw its presence from many overseas settlements in 1774. On 20 May 1776 the British forces under the command of Royal Naval Lieutenant Clayton formally left Port Egmont, while leaving a plaque asserting Britain's continuing sovereignty over the islands. For the next four years, British sealers Sealer may refer either to a person or ship engaged in seal hunting, or to a sealant; associated terms include:

Seal hunting

* Sealer Hill, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica

* Sealers' Oven, bread oven of mud and stone built by sealers around 18 ...

used Egmont as a base for their activities in the South Atlantic. This ended in 1780 when they were forced to leave by Spanish authorities who then ordered that the British colony be destroyed.

The Spanish withdrew from the islands under pressure as a result of the Napoleonic invasion and the Argentine War of Independence. The Spanish garrison of Puerto Soledad

Puerto Soledad (''Puerto de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad'', en, Port Solitude) was a Spanish military outpost and penal colony on the Falkland Islands, situated at an inner cove of Berkeley Sound (french: ,Dom Pernety, Antoine-Joseph. ''Journ ...

was removed to Montevideo in 1811 aboard the brigantine ''Gálvez'' under an order signed by Francisco Javier de Elío

Francisco Javier de Elío y Olóndriz (Pamplona, 1767 – Valencia, 1822), was a Spanish soldier, governor of Montevideo. He was also instrumental in the Absolutist repression after the restoration of Ferdinand VII as King of Spain. For th ...

. On departure, the Spanish also left a plaque proclaiming Spain's sovereignty over the islands as the British had done 35 years before. The total depopulation of the Falkland Islands took place.

Inter-colonial period

Following the departure of the Spanish settlers, the Falkland Islands became the domain of whalers and sealers who used the islands to shelter from the worst of the South Atlantic weather. By merit of their location, the Falkland Islands have often been the last refuge for ships damaged at sea. Most numerous among those using the islands were British and American sealers, where typically between 40 and 50 ships were engaged in exploitingfur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family '' Otariidae''. They are much more closely related to sea lions than true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), relatively l ...

s. This represents an itinerant population of up to 1,000 sailors.

''Isabella''

On 8 February 1813 ''Isabella'', a British ship of 193 tons en route from Sydney toLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, ran aground off the coast of Speedwell Island

Speedwell Island (formerly Eagle Island; Spanish ''Isla Águila'') is one of the Falkland Islands, lying in the Falkland Sound, southwest of Lafonia, East Falkland.

The island has an area of , measuring approximately from north to south and ...

, then known as Eagle Island. Among the ship's 54 passengers and crew, all of whom survived the wreck, was the United Irish general and exile Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the secession of the South. He returned to Ke ...

, who subsequently detailed the ordeal in his memoirs. Also aboard had been the heavily pregnant Joanna Durie, who on 21 February 1813 gave birth to Elizabeth Providence Durie.

The next day, 22 February 1813, six men who had volunteered to seek help from any nearby Spanish outposts that they could find set out in one of the Isabella's longboats. Braving the South Atlantic in a boat little more than long, they made landfall on the mainland at the River Plate just over a month later. The British gun brig under the command of Lieutenant William D'Aranda was sent to rescue the survivors.

On 5 April Captain Charles Barnard of the American sealer ''Nanina'' was sailing off the shore of Speedwell Island, with a discovery boat deployed looking for seals. Having seen smoke and heard gunshots the previous day, he was alert to the possibility of survivors of a ship wreck. This suspicion was heightened when the crew of the boat came aboard and informed Barnard that they had come across a new moccasin as well as the partially butchered remains of a seal. At dinner that evening, the crew observed a man approaching the ship who was shortly joined by eight to ten others. Both Barnard and the survivors from ''Isabella'' had harboured concerns the other party was Spanish and were relieved to discover their respective nationalities.

Barnard dined with the ''Isabella'' survivors that evening and finding that the British party were unaware of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

informed the survivors that technically they were at war with each other. Nevertheless, Barnard promised to rescue the British party and set about preparations for the voyage to the River Plate. Realising that they had insufficient stores for the voyage he set about hunting wild pigs and otherwise acquiring additional food. While Barnard was gathering supplies, however, the British took the opportunity to seize ''Nanina'' and departed leaving Barnard, along with one member of his own crew and three from ''Isabella'', marooned. Shortly thereafter, ''Nancy'' arrived from the River Plate and encountered ''Nanina'', whereupon Lieutenant D'Aranda rescued the erstwhile survivors of ''Isabella'' and took ''Nanina'' itself as a prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

.

Barnard and his party survived for eighteen months marooned on the islands until the British whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

s and '' Asp'' rescued them in November 1814. The British admiral in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

had requested their masters to divert to the area to search for the American crew. In 1829, Barnard published an account of his survival entitled ''A Narrative of the Sufferings and Adventures of Capt Charles H. Barnard''.

Argentine colonisation attempts

In March 1820, , a privately owned frigate that was operated as a

In March 1820, , a privately owned frigate that was operated as a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

under a license issued by the United Provinces of the River Plate

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

, under the command of American Colonel David Jewett, set sail looking to capture Spanish ships as prizes. He captured ''Carlota'', a Portuguese ship, which was considered an act of piracy. A storm resulted in severe damage to ''Heroína'' and sank the prize ''Carlota'', forcing Jewett to put into Puerto Soledad for repairs in October 1820.

Captain Jewett sought assistance from the British explorer James Weddell

James Weddell (24 August 1787 – 9 September 1834) was a British sailor, navigator and seal hunter who in February 1823 sailed to latitude of 74° 15′ S—a record 7.69 degrees or 532 statute miles south of the Antarc ...

. Weddell reported the letter he received from Jewett as:

Sir, I have the honor of informing you that I have arrived in this port with a commission from the Supreme Government of the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata to take possession of these islands on behalf of the country to which they belong by Natural Law. While carrying out this mission I want to do so with all the courtesy and respect all friendly nations; one of the objectives of my mission is to prevent the destruction of resources necessary for all ships passing by and forced to cast anchor here, as well as to help them to obtain the necessary supplies, with minimum expenses and inconvenience. Since your presence here is not in competition with these purposes and in the belief that a personal meeting will be fruitful for both of us, I invite you to come aboard, where you'll be welcomed to stay as long as you wish; I would also greatly appreciate your extending this invitation to any other British subject found in the vicinity; I am, respectfully yours. Signed, Jewett, Colonel of the Navy of the United Provinces of South America and commander of the frigate ''Heroína''.Many modern authors report this letter as representing the declaration issued by Jewett.Laurio H. Destéfani, ''The Malvinas, the South Georgias and the South Sandwich Islands, the conflict with Britain'', Buenos Aires, 1982 Jewett's ship received Weddell's assistance in obtaining anchorage off

Port Louis

Port Louis (french: Port-Louis; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Polwi or , ) is the capital city of Mauritius. It is mainly located in the Port Louis District, with a small western part in the Black River District. Port Louis is the country's e ...

. Weddell reported only 30 seamen and 40 soldiers fit for duty out of a crew of 200, and how Jewett slept with pistols over his head following an attempted mutiny earlier in the voyage. On 6 November 1820, Jewett raised the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate (a predecessor of modern-day Argentina) and claimed possession of the islands. In the words of Weddell, "In a few days, he took formal possession of these islands for the patriot government of Buenos Ayres, read a declaration under their colours, planted on a port in ruins, and fired a salute of twenty-one guns."Weddell, James''A Voyage Towards the South Pole''

London, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, 1827 Jewett departed from the Falkland Islands in April 1821. In total he had spent no more than six months on the island, entirely at Port Luis. In 1822, Jewett was accused of piracy by a Portuguese court, but by that time he was in Brazil.

Luis Vernet's enterprise

In 1823, the United Provinces of the River Plate granted

In 1823, the United Provinces of the River Plate granted fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

rights to Jorge Pacheco and Luis Vernet

Luis Vernet (born Louis Vernet; March 6, 1791 – January 17, 1871) was a merchant from Hamburg of Huguenot descent. Vernet established a settlement on East Falkland in 1828, after first seeking approval from both the British and Argentine autho ...

. Travelling to the islands in 1824, the first expedition failed almost as soon as it landed, and Pacheco chose not to continue with the venture. Vernet persisted, but the second attempt, delayed until winter 1826 by a Brazilian blockade, was also unsuccessful. The expedition intended to exploit the feral

A feral () animal or plant is one that lives in the wild but is descended from domesticated individuals. As with an introduced species, the introduction of feral animals or plants to non-native regions may disrupt ecosystems and has, in some ...

cattle on the islands but the boggy

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; ...

conditions meant the gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia. Gauchos became greatly admired and ...

s could not catch cattle in their traditional way. Vernet was by now aware of conflicting British claims to the islands and sought permission from the British consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of diplomatic mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth c ...

before departing for the islands.

In 1828, the United Provinces government granted Vernet all of East Falkland including all its resources, and exempted him from taxation if a colony could be established within three years. He took settlers, including British Captain Matthew Brisbane (who had sailed to the islands earlier with Weddell), and before leaving once again sought permission from the British Consulate in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

. The British asked for a report for the British government on the islands, and Vernet asked for British protection should they return.A brief history of the Falkland Islands Part 3 - Louis Vernet: The Great Entrepreneur, Accessed 2007-07-19 On 10 June 1829, Vernet was designated as 'civil and military commandant' of the islands (no governor was ever appointed) and granted a monopoly on seal hunting rights. A protest was lodged by the British Consulate in Buenos Aires. By 1831, the colony was successful enough to be advertising for new colonists, although 's report suggests that the conditions on the islands were quite miserable.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's visit in 1833 confirmed the squalid conditions in the settlement, although Captain Matthew Brisbane

Matthew Brisbane (1787 – 8 August 1833) was a Scottish mariner, sealer and notable figure in the early history of the Falkland Islands.

Early life

Little is known of Brisbane's early life. He was born in Perth, Tayside in 1787 but his ...

(Vernet's deputy) later claimed that this was the result of the ''Lexington'' raid.Fitzroy, R., ''VOYAGES OF THE ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE. VOLUME II.''Accessed 2007-10-02

USS ''Lexington'' raid

In 1831, Vernet attempted to assert his monopoly on seal hunting rights. This led him to capture the American ships ''Harriet'', ''Superior'' and ''Breakwater''. As a reprisal, the United States consul in Buenos Aires sent CaptainSilas Duncan

Silas M. Duncan (178814 September 1834) was an officer in the United States Navy during the War of 1812.

Born in Rockaway Township, New Jersey, Duncan was appointed midshipman 15 November 1809. While third lieutenant of ''Saratoga'' during the B ...

of USS ''Lexington'' to recover the confiscated property. After finding what he considered proof that at least four American fishing ships had been captured, plundered, and even outfitted for war, Duncan took seven prisoners aboard ''Lexington'' and charged them with piracy.

Also taken on board, Duncan reported, "were the whole of the (Falklands') population consisting of about forty persons, with the exception of some 'gauchos', or cowboys who were encamped in the interior." The group, principally German citizens from Buenos Aires, "appeared greatly rejoiced at the opportunity thus presented of removing with their families from a desolate region where the climate is always cold and cheerless and the soil extremely unproductive". However, about 24 people did remain on the island, mainly gauchos and several Charrúa

The Charrúa were an indigenous people or Indigenous Nation of the Southern Cone in present-day Uruguay and the adjacent areas in Argentina ( Entre Ríos) and Brazil ( Rio Grande do Sul). They were a semi-nomadic people who sustained themsel ...

Indians, who continued to trade on Vernet's account.

Measures were taken against the settlement. The log of ''Lexington'' reports destruction of arms and a powder store, while settlers remaining later said that there was great damage to private property. Towards the end of his life, Luis Vernet authorised his sons to claim on his behalf for his losses stemming from the raid. In the case lodged against the US Government for compensation, rejected by the US Government of President Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in America ...

in 1885, Vernet Vernet is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Painters

* Antoine Vernet (1689-1753), French painter, father of Claude Joseph Vernet

* Claude Joseph Vernet

Claude-Joseph Vernet (14 August 17143 December 1789) was a French painter. ...

stated that the settlement was destroyed.

Penal colony and mutiny

In the aftermath of the ''Lexington'' incident, Major Esteban Mestivier was commissioned by the Buenos Aires government to set up apenal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

. He arrived at his destination on 15 November 1832 but his soldiers mutinied and killed him. The mutiny was suppressed by armed sailors from the French whaler ''Jean Jacques'', whilst Mestivier's widow was taken on board the British sealer ''Rapid''. ''Sarandí'' returned on 30 December 1832 and Major José María Pinedo

José María Pinedo (21 June 1795 – 19 February 1885) was a commander in the navy of the United Provinces of the River Plate, one of the precursor states of what is now known as Argentina. He took part in the Argentine War of Independence, the ...

took charge of the settlement.

British return

The Argentinian assertions of sovereignty provided the spur for Britain to send a naval task force in order to finally and permanently return to the islands.

On 3 January 1833, Captain James Onslow, of the brig-sloop , arrived at Vernet's settlement at Port Louis to request that the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate be replaced with the British one, and for the administration to leave the islands. While Major José María Pinedo, commander of the schooner ''Sarandí'', wanted to resist, his numerical disadvantage was obvious, particularly as a large number of his crew were British mercenaries who were unwilling to fight their own countrymen. Such a situation was not unusual in the newly independent states in Latin America, where land forces were strong, but navies were frequently quite undermanned. As such he protested verbally, but departed without a fight on 5 January. Argentina claims that Vernet's colony was also expelled at this time, though sources from the time appear to dispute this, suggesting that the colonists were encouraged to remain initially under the authority of Vernet's storekeeper, William Dickson and later his deputy, Matthew Brisbane.

Initial British plans for the Islands were based upon the continuation of Vernet's settlement at Port Louis. An Argentine immigrant of Irish origin, William Dickson, was appointed as the British representative and provided with a flagpole and flag to be flown whenever ships were in harbour. In March 1833, Vernet's Deputy, Matthew Brisbane returned and presented his papers to Captain

The Argentinian assertions of sovereignty provided the spur for Britain to send a naval task force in order to finally and permanently return to the islands.

On 3 January 1833, Captain James Onslow, of the brig-sloop , arrived at Vernet's settlement at Port Louis to request that the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate be replaced with the British one, and for the administration to leave the islands. While Major José María Pinedo, commander of the schooner ''Sarandí'', wanted to resist, his numerical disadvantage was obvious, particularly as a large number of his crew were British mercenaries who were unwilling to fight their own countrymen. Such a situation was not unusual in the newly independent states in Latin America, where land forces were strong, but navies were frequently quite undermanned. As such he protested verbally, but departed without a fight on 5 January. Argentina claims that Vernet's colony was also expelled at this time, though sources from the time appear to dispute this, suggesting that the colonists were encouraged to remain initially under the authority of Vernet's storekeeper, William Dickson and later his deputy, Matthew Brisbane.

Initial British plans for the Islands were based upon the continuation of Vernet's settlement at Port Louis. An Argentine immigrant of Irish origin, William Dickson, was appointed as the British representative and provided with a flagpole and flag to be flown whenever ships were in harbour. In March 1833, Vernet's Deputy, Matthew Brisbane returned and presented his papers to Captain Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

of , which coincidentally happened to be in harbour at the time. Fitzroy encouraged Brisbane to continue with Vernet's enterprise with the proviso that whilst private enterprise was encouraged, Argentine assertions of sovereignty would not be welcome.

Brisbane reasserted his authority over Vernet's settlement and recommenced the practice of paying employees in promissory notes. Due to Vernet's reduced status, the promissory notes were devalued, which meant that the employees received fewer goods at Vernet's stores for their wages. After months of freedom following the ''Lexington'' raid this accentuated dissatisfaction with the leadership of the settlement. In August 1833, under the leadership of Antonio Rivero, a gang of Creole and Indian gauchos ran amok in the settlement. Armed with muskets obtained from American sealers, the gang killed five members of Vernet's settlement including both Dickson and Brisbane. Shortly afterward the survivors fled Port Louis, seeking refuge on Turf Island in Berkeley Sound until rescued by the British sealer ''Hopeful'' in October 1833.

Lt Henry Smith was installed as the first British resident in January 1834. One of his first actions was to pursue and arrest Rivero's gang for the murders committed the previous August. The gang was sent for trial in London but could not be tried as the Crown Court did not have jurisdiction over the Falkland Islands. In the British colonial system, colonies had their own, distinct governments, finances, and judicial systems. Rivero was not tried and sentenced because the British local government and local judiciary had not yet been installed in 1834; these were created later, by the 1841 British Letters Patent. Subsequently, Rivero has acquired the status of a folk hero in Argentina, where he is portrayed as leading a rebellion against British rule. Ironically it was the actions of Rivero that were responsible for the ultimate demise of Vernet's enterprise on the Falklands.

Charles Darwin revisited the Falklands in 1834; the settlements Darwin and Fitzroy Fitzroy or FitzRoy may refer to:

People As a given name

*Several members of the Somerset family (Dukes of Beaufort) have this as a middle-name:

**FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan (1788–1855)

** Henry Charles FitzRoy Somerset, 8th Duke of Beau ...

both take their names from this visit.

After the arrest of Rivero, Smith set about restoring the settlement at Port Louis, repairing the damage done by the ''Lexington'' raid and renaming it 'Anson's Harbour'. Lt Lowcay succeeded Smith in April 1838, followed by Lt Robinson in September 1839 and Lt Tyssen in December 1839.

Vernet later attempted to return to the Islands but was refused permission to return. The British Crown reneged on promises and refused to recognise rights granted by Captain Onslow at the time of the reoccupation. Eventually, after travelling to London, Vernet received paltry compensation for horses shipped to Port Louis many years before. G.T. Whittington obtained a concession of from Vernet that he later exploited with the formation of the Falkland Islands Commercial Fishery and Agricultural Association. Islas del Atlántico Sur, Islas Malvinas, Historia, Ocupación Inglesa: Port Stanley, Accessed 2007-10-02

British colonisation

Immediately following their return to the Falkland Islands and the failure of Vernet's settlement, the British maintained Port Louis as a military outpost. There was no attempt to colonise the islands following the intervention, instead there was a reliance upon the remaining rump of Vernet's settlement. Lt. Smith received little support from the

Immediately following their return to the Falkland Islands and the failure of Vernet's settlement, the British maintained Port Louis as a military outpost. There was no attempt to colonise the islands following the intervention, instead there was a reliance upon the remaining rump of Vernet's settlement. Lt. Smith received little support from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and the islands developed largely on his initiative but he had to rely on a group of armed gauchos to enforce authority and protect British interests. Smith received advice from Vernet in this regard, and in turn continued to administer Vernet's property and provide him with regular accounts. His superiors later rebuked him for his ideas and actions in promoting the development of the small settlement in Port Louis. In frustration, Smith resigned but his successors Lt. Lowcay and Lt. Tyssen did not continue with the initiatives Smith had pursued and the settlement began to stagnate.

In 1836, East Falkland was surveyed by Admiral George Grey, and further in 1837 by Lowcay. Admiral George Grey, conducting the geographic survey in November 1836 had the following to say about their first view of East Falkland:

Pressure to develop the islands as a colony began to build as the result of a campaign mounted by British merchant G. T. Whittington. Whittington formed the Falkland Islands Commercial Fishery and Agricultural Association and (based on information indirectly obtained from Vernet) published a pamphlet entitled "The Falkland Islands". Later a petition signed by London merchants was presented to the British Government demanding the convening of a public meeting to discuss the future development of the Falkland Islands. Whittington petitioned the Colonial Secretary, Lord Russell, proposing that his association be allowed to colonise the islands. In May 1840, the British Government made the decision to colonise the Falkland Islands.

Unaware of the decision by the British Government to colonise the islands, Whittington grew impatient and decided to take action of his own initiative. Obtaining two ships, he sent his brother, J. B. Whittington, on a mission to land stores and settlers at Port Louis. On arrival he presented his claim to land that his brother had bought from Vernet. Lt. Tyssen was taken aback by Whittington's arrival, indicating that he had no authority to allow this; however, he was unable to prevent the party from landing. Whittington constructed a large house for his party, and using a salting house built by Vernet established a fish-salting business. A Brief History of the Falkland Islands, Part 4 - The British Colonial Era, Accessed 2007-10-02

Establishment of Port Stanley

In 1833 the United Kingdom asserted authority over the Falkland Islands and

In 1833 the United Kingdom asserted authority over the Falkland Islands and Richard Clement Moody

Richard Clement Moody Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Military Merit of France (13 February 1813 – 31 March 1887) was a British governor, engineer, architect and soldier. He is best known for being the founder and the first Lieutenant ...

, a highly esteemed Royal Engineer

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

, was appointed as Lieutenant Governor of the islands. This post was renamed Governor of the Falkland Islands

The governor of the Falkland Islands is the representative of the British Crown in the Falkland Islands, acting "in His Majesty's name and on His Majesty's behalf" as the islands' ''de facto'' head of state in the absence of the British monarch ...

in 1843, when he also became Commander-in-Chief of the Falkland Islands. Moody left England for Falkland on 1 October 1841 aboard the ship ''Hebe'' and

arrived in Anson's Harbour later that month. He was accompanied by twelve sappers and miners and their families; together with Whittington's colonists this brought the population of Anson's Harbour to approximately 50. When Moody arrived, the Falklands was 'almost in a state of anarchy', but he used his powers 'with great wisdom and moderation'Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Volume 90, Issue 1887, 1887, pp. 453-455, OBITUARY. MAJOR-GENERAL RICHARD CLEMENT MOODY, R.E., 1813-1887. to develop the Islands' infrastructure and, commanding detachment of sappers, erected government offices, a school and barracks, residences, ports, and a new road system.

In 1842, Moody was instructed by Lord Stanley

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the en ...

the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies to report on the potential of the Port William area as the site of the new capital. Moody assigned the task of surveying the area to Captain Ross, leader of the Antarctic Expedition. Captain Ross delivered his report in 1843, concluding that Port William afforded a good deep-water anchorage for naval vessels, and that the southern shores of Port Jackson was a suitable location for the proposed settlement. Moody accepted the recommendation of Ross and construction of the new settlement started in July 1843. Inn July 1845, at Moody's suggestion, the new capital of the islands was officially named Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a popula ...

after Lord Stanley. Not everyone was enthused with the selection of the location of the new capital, J. B. Whittington famously remarked that "Of all the miserable bog holes, I believe that Mr Moody has selected one of the worst for the site of his town."

The structure of the Colonial Government was established in 1845 with the formation of the Legislative Council and Executive Council and work on the construction of Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

commenced. The following year, the first officers appointed to the Colonial Government took their posts; by this time a number of residences, a large storage shed, carpenter's shop and blacksmith's shop had been completed and the Government Dockyard laid out. In 1845 Moody introduced tussock grass

Tussock grasses or bunch grasses are a group of grass species in the family Poaceae. They usually grow as singular plants in clumps, tufts, hummocks, or bunches, rather than forming a sod or lawn, in meadows, grasslands, and prairies. As perenni ...

into Great Britain from Falkland, for which he received the gold medal of the Royal Agricultural Society. The Coat of arms of the Falkland Islands

The coat of arms of the Falkland Islands is the heraldic device consisting of a shield charged with a ram on tussock grass in a blue field at the top and a sailing ship on white and blue wavy lines underneath. Adopted in 1948, it has been the ...

notably includes an image of tussock grass. Moody returned to England in February 1849. Moody Brook

Moody Brook is a small watercourse that flows into Stanley Harbour on East Falkland, Falkland Islands. It is near Stanley, just to the north west, and was formerly the location of the town barracks, which were attacked in Operation Rosario ...

is named after him.Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Richard Clement Moody

With the establishment of the deep-water anchorage and improvements in port facilities, Stanley saw a dramatic increase in the number of visiting ships in the 1840s in part due to the California Gold Rush. A boom in ship provisioning and ship-repair resulted, aided by the notoriously bad weather in the South Atlantic and around Cape Horn. Stanley and the Falkland Islands are famous as the repository of many wrecks of 19th-century ships that reached the islands only to be condemned as unseaworthy and were often employed as floating warehouses by local merchants.

At one point in the 19th century, Stanley became one of the world's busiest ports. However, the ship-repair trade began to slacken off in 1876 with the establishment of the Plimsoll line

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

, which saw the elimination of the so-called coffin ships and unseaworthy vessels that might otherwise have ended up in Stanley for repair. With the introduction of increasingly reliable iron steamships

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

in the 1890s the trade declined further and was no longer viable following the opening of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

in 1914. Port Stanley continued to be a busy port supporting whaling and sealing activities in the early part of the 20th century, British warships (and garrisons) in the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

and the fishing and cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports-of-call, where passengers may go on tours known as ...

industries in the latter half of the century.

Chelsea Pensioners

A Chelsea Pensioner, or In-Pensioner, is a resident at the Royal Hospital Chelsea, a retirement home and nursing home for former members of the British Army located in Chelsea, London. The Royal Hospital Chelsea is home to 300 retired British sol ...

and their families. The Chelsea Pensioners were to form the permanent garrison and police force, taking over from the Royal Sappers and Miners Regiment which had garrisoned the early colony.

The Exchange Building opened in 1854; part of the building was later used as a church. 1854 also saw the establishment of Marmont Row, including the Eagle Inn, now known as the Upland Goose Hotel. In 1887, Jubilee Villas were built to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

. Jubilee Villas are a row of brick built houses that follow a traditional British pattern; positioned on Ross road near the waterfront, they became an iconic image during the Falklands War.

Peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficient ...

is common on the islands and has traditionally been exploited as a fuel. Uncontrolled exploitation of this natural resource led to peat slips in 1878 and 1886. The 1878 peat slip resulted in the destruction of several houses, whilst the 1886 peat slip resulted in the deaths of two women and the destruction of the Exchange Building.

Christ Church Cathedral was consecrated in 1892 and completed in 1903. It received its famous whalebone arch, constructed from the jaws of two blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

s, in 1933 to commemorate the centenary of continuous British administration. Also consecrated in 1892 was the Tabernacle United Free Church, constructed from an imported timber kit.

Development of agriculture and the Camp

A few years after the British had established themselves in the islands, a number of new British settlements were started. Initially many of these settlements were established in order to exploit the feral cattle on the islands. Following the introduction of the Cheviot breed of sheep to the islands in 1852, sheep farming became the dominant form of agriculture on the Islands.

A few years after the British had established themselves in the islands, a number of new British settlements were started. Initially many of these settlements were established in order to exploit the feral cattle on the islands. Following the introduction of the Cheviot breed of sheep to the islands in 1852, sheep farming became the dominant form of agriculture on the Islands.

Salvador Settlement

Salvador Settlement, also called Salvador, Salvador Settlement Corral, is a small harbour and settlement on East Falkland, in the Falkland Islands, It is on the north east coast, on the south shore of Port Salvador. It is one of a handful of S ...

was one of the earliest, being started in the 1830s, by a Gibraltarian immigrant (hence its other name of "Gibraltar Settlement"), and it is still run by his descendants, the Pitalugas.

Vernet furnished Samuel Fisher Lafone, a British merchant operating from Montevideo, with details of the Falkland Islands including a map. Sensing that the exploitation of feral cattle on the islands would be a lucrative venture, in 1846 he negotiated a contract with the British Government that gave him exclusive rights to this resource. Until 1846 Moody had allotted feral cattle to new settlers and the new agreement not only prevented this but made Stanley dependent upon Lafone for supplies of beef