This history of the Byzantine Empire covers the history of the

Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

from

late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

until the

Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD. Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during which the Roman Empire's

east and west divided

Division is one of the four basic operations of arithmetic, the ways that numbers are combined to make new numbers. The other operations are addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

At an elementary level the division of two natural numb ...

. In 285, the

emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Diocletian (r. 284–305) partitioned the Roman Empire's administration into eastern and western halves. Between 324 and 330,

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

(r. 306–337) transferred the main capital from

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to

Byzantium, later known as ''Constantinople'' ("City of Constantine") and ''Nova Roma'' ("New Rome"). Under

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

(r. 379–395),

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

became the Empire's official

state religion and others such as

Roman polytheism

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

were

proscribed. And finally, under the reign of

Heraclius (r. 610–641), the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Thus, although it continued the Roman state and maintained Roman state traditions, modern historians distinguish Byzantium from

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

insofar as it was oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by

Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Chur ...

rather than

Roman polytheism

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

.

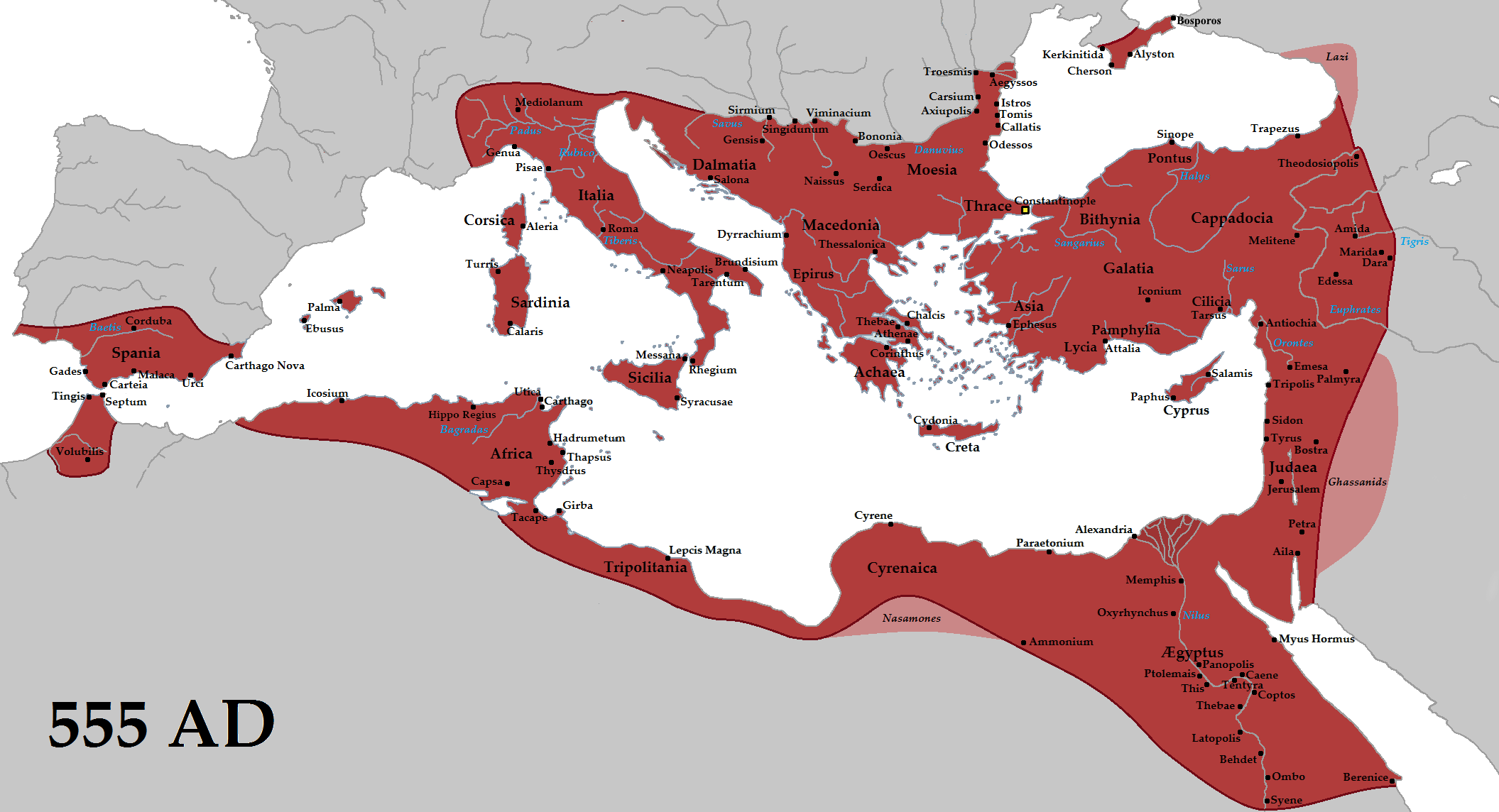

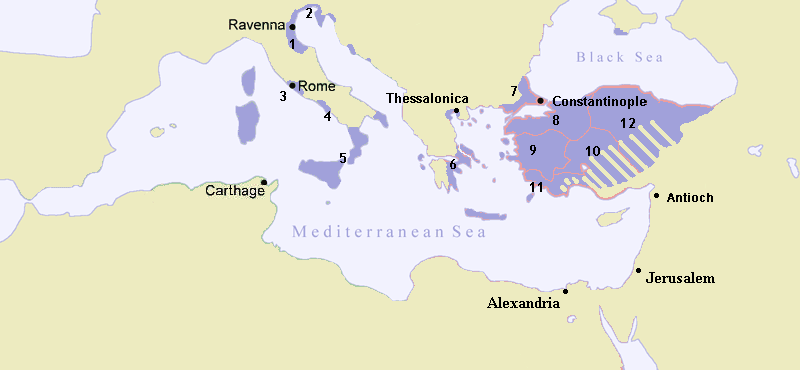

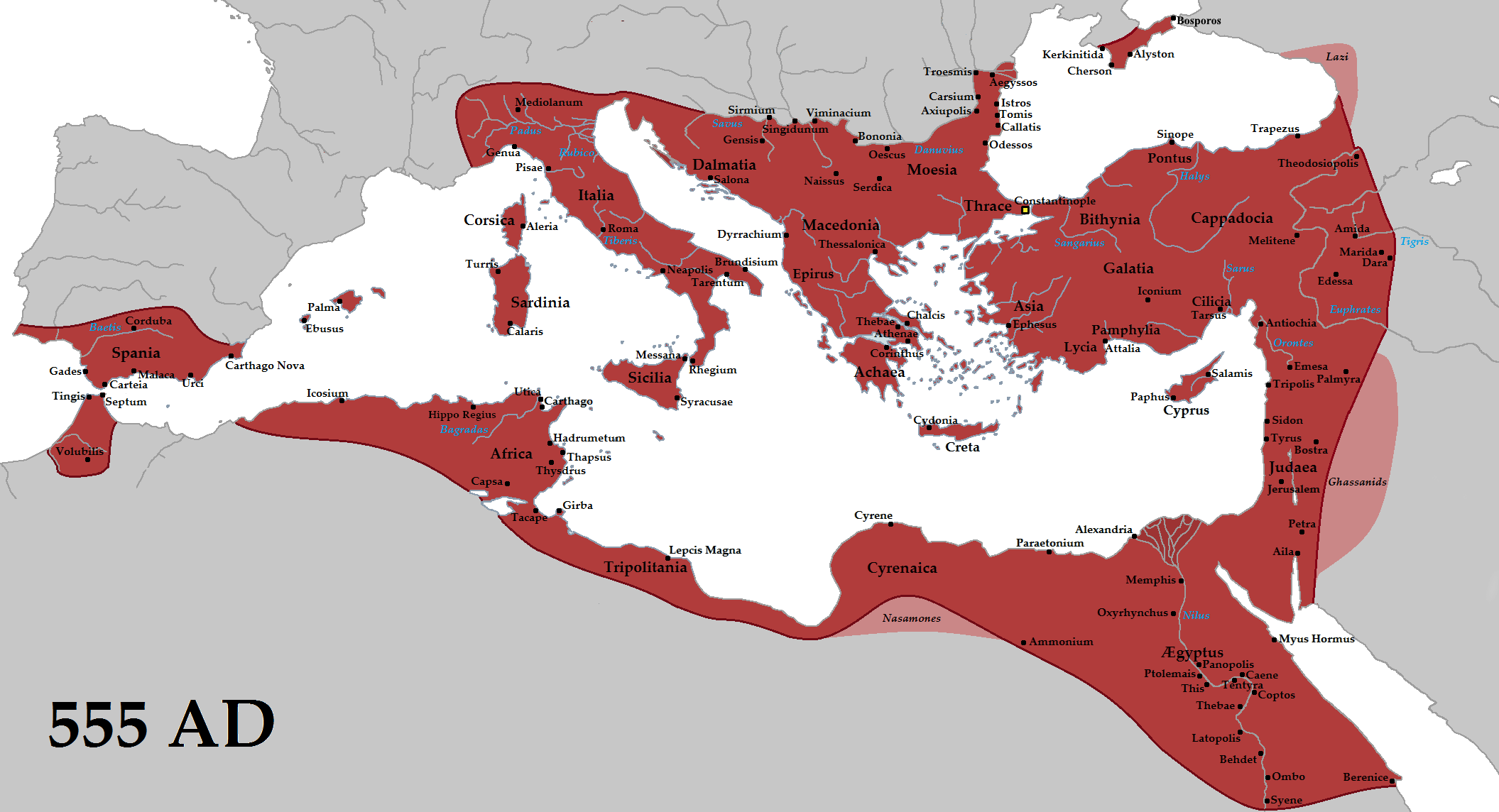

The borders of the Empire evolved significantly over its existence, as it went through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

(r. 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

coast, including north Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. During the reign of

Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

(r. 582–602), the Empire's eastern frontier was expanded and the north stabilised. However, his assassination caused a

two-decade-long war with

Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

which exhausted the Empire's resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the

Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 7th century. In a matter of years the Empire lost its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, to the Arabs.

During the

Macedonian dynasty

The Macedonian dynasty (Greek: Μακεδονική Δυναστεία) ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, following the Amorian dynasty. During this period, the Byzantine state reached its greatest extent since the Muslim conquests, a ...

(9th–11th centuries), the Empire again expanded and experienced a two-century long

renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, which came to an end with the loss of much of Asia Minor to the

Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

after the

Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle opened the way for the Turks to settle in

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

as a homeland.

The final centuries of the Empire exhibited a general trend of decline. It struggled to

recover during the 12th century, but was delivered a mortal blow during the

Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked and the Empire

dissolved and divided into competing Byzantine Greek and

Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople and

re-establishment of the Empire in 1261, Byzantium remained only one of several small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence. Its remaining territories were

progressively annexed by the Ottomans over the 15th century. The

Fall of Constantinople to the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in 1453 finally ended the Roman Empire.

Tetrarchy

During the 3rd century, three crises threatened the Roman Empire: external invasions, internal civil wars and an economy riddled with weaknesses and problems.

[Bury (1923)]

1

br />* Fenner

The city of Rome gradually became less important as an administrative centre. The

crisis of the 3rd century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensio ...

displayed the defects of the heterogeneous system of government that

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

had established to administer his immense dominion. His successors had introduced some modifications, but events made it clearer that a new, more centralized and more uniform system was required.

[Bury (1923)]

1

/ref>

Diocletian was responsible for creating a new administrative system (the tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

).Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

''. Each Augustus was then to adopt a young colleague, or ''Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

'', to share in the rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. After the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian, however, the tetrachy collapsed, and Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

replaced it with the dynastic principle of hereditary succession.

* Gibbon (1906), II,

Constantine I and his successors

Constantine moved the seat of the Empire, and introduced important changes into its civil and religious constitution.

Constantine moved the seat of the Empire, and introduced important changes into its civil and religious constitution.[Gibbon (1906), III, ] In 330, he founded Constantinople as a second Rome on the site of Byzantium, which was well-positioned astride the trade routes between East and West; it was a superb base from which to guard the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

river, and was reasonably close to the Eastern frontiers. Constantine also began the building of the great fortified walls, which were expanded and rebuilt in subsequent ages. J. B. Bury

John Bagnell Bury (; 16 October 1861 – 1 June 1927) was an Anglo-Irish historian, classical scholar, Medieval Roman historian and philologist. He objected to the label "Byzantinist" explicitly in the preface to the 1889 edition of his ''Lat ...

asserts that "the foundation of Constantinople ..inaugurated a permanent division between the Eastern and Western, the Greek and the Latin, halves of the Empire—a division to which events had already pointed—and affected decisively the whole subsequent history of Europe

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first ea ...

."[Bury (1923)]

1

br />* Esler (2000), 1081 He stabilized the coinage (the gold solidus

Solidus (Latin for "solid") may refer to:

* Solidus (coin), a Roman coin of nearly solid gold

* Solidus (punctuation), or slash, a punctuation mark

* Solidus (chemistry), the line on a phase diagram below which a substance is completely solid

* ...

that he introduced became a highly prized and stable currency[Esler (2000), 1081]), and made changes to the structure of the army. Under Constantine, the Empire had recovered much of its military strength and enjoyed a period of stability and prosperity. He also reconquered southern parts of Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

, after defeating the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

in 332, and he was planning a campaign against Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

as well. To divide administrative responsibilities, Constantine replaced the single praetorian prefect, who had traditionally exercised both military and civil functions, with regional prefects enjoying civil authority alone. In the course of the 4th century, four great sections emerged from these Constantinian beginnings, and the practice of separating civil from military authority persisted until the 7th century.[Bury (1923)]

25–26

/ref>

Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

inaugurated the Constantine's Bridge (Danube)

Constantine's Bridge ( bg, Константинов мост, ''Konstantinov most''; ro, Podul lui Constantin cel Mare) was a Roman bridge over the Danube used to reconquer Dacia. It was completed in 328 AD and remained in use for four decades ...

at Sucidava, (today Celei in Romania) in 328, in order to reconquer Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

, a province that had been abandoned under Aurelian. He won a victory in the war and extended his control over the South Dacia, as remains of camps and fortifications in the region indicate.

Under Constantine, Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the state, but enjoyed imperial preference, since the Emperor supported it with generous privileges: clerics were exempted from personal services and taxation, Christians were preferred for administrative posts, and bishops were entrusted with judicial responsibilities.[Esler (2000), 1081]

* Mousourakis (2003), 327–328 Constantine established the principle that emperors should not settle questions of doctrine, but should summon general ecclesiastical councils for that purpose. The Synod of Arles

Arles (ancient Arelate) in the south of Roman Gaul (modern France) hosted several councils or synods referred to as ''Concilium Arelatense'' in the history of the early Christian church.

Council of Arles in 314

The first council of Arles"Arles, S ...

was convened by Constantine, and the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

showcased his claim to be head of the Church.[Bury (1923)]

163

/ref>

The state of the Empire in 395 may be described in terms of the outcome of Constantine's work. The dynastic principle was established so firmly that the emperor who died in that year, Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, could bequeath the imperial office jointly to his sons: Arcadius

Arcadius ( grc-gre, Ἀρκάδιος ; 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to 408. He was the eldest son of the ''Augustus'' Theodosius I () and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (). Arcadius ruled the ...

in the East and Honorius in the West. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over the full extent of the empire in both its halves.tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

and pay foreign mercenaries. Throughout the fifth century, various invading armies overran the Western Empire but spared the east. Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

further fortified the walls of Constantinople, leaving the city impervious to most attacks; the walls were not breached until 1204. To fend off the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

of Attila, Theodosius gave them subsidies (purportedly 300 kg (700 lb) of gold).[Nathan]

Theodosius II (408–450 AD)

/ref> Moreover, he favored merchants living in Constantinople who traded with the Huns and other foreign groups.

His successor, Marcian, refused to continue to pay this exorbitant sum. However, Attila had already diverted his attention to the Western Roman Empire. After he died in 453, his empire collapsed and Constantinople initiated a profitable relationship with the remaining Huns, who would eventually fight as mercenaries in Byzantine armies.

Leonid dynasty

Leo I

The LEO I (Lyons Electronic Office I) was the first computer used for commercial business applications.

The prototype LEO I was modelled closely on the Cambridge EDSAC. Its construction was overseen by Oliver Standingford, Raymond Thompson and ...

succeeded Marcian as emperor, and after the fall of Attila, the true chief in Constantinople was the Alan general Aspar

Flavius Ardabur Aspar (Greek: Άσπαρ, fl. 400471) was an Eastern Roman patrician and ''magister militum'' ("master of soldiers") of Alanic-Gothic descent. As the general of a Germanic army in Roman service, Aspar exerted great influence o ...

. Leo I managed to free himself from the influence of the non-Orthodox chief by supporting the rise of the Isauri

Isauria ( or ; grc, Ἰσαυρία), in ancient geography, is a rugged, isolated, district in the interior of Asia Minor, of very different extent at different periods, but generally covering what is now the district of Bozkır and its surro ...

ans, a semi- barbarian tribe living in southern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. Aspar and his son Ardabur were murdered in a riot in 471, and henceforth, Constantinople restored Orthodox leadership for centuries.

Leo was also the first emperor to receive the crown not from a military leader, but from the Patriarch of Constantinople, representing the ecclesiastical hierarchy. This change became permanent, and in the Middle Ages the religious characteristic of the coronation completely supplanted the old military form. In 468, Leo unsuccessfully attempted to reconquer North Africa from the Vandals.[Cameron (2000), 553] By that time, the Western Roman Empire was restricted to Italy and the lands south of the Danube as far as the Balkans (the Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ...

and Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

had been invading and settling Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

since the early decades of the 5th century; the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

and Suebi had possessed portions of Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hisp ...

since 417, and the Vandals had entered Africa in 429; Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

was contested by the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

under Clovis I, Burgundians, Bretons

The Bretons (; br, Bretoned or ''Vretoned,'' ) are a Celtic ethnic group native to Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Brittonic speakers who emigrated from southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwall and Devon, mo ...

, Visigoths and some Roman remnants; and Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

was destined to rule in Italy until 526Ariadne

Ariadne (; grc-gre, Ἀριάδνη; la, Ariadne) was a Cretan princess in Greek mythology. She was mostly associated with mazes and labyrinths because of her involvement in the myths of the Minotaur and Theseus. She is best known for havi ...

to the Isaurian Tarasicodissa, who took the name Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

. When Leo died in 474, Zeno and Ariadne's younger son succeeded to the throne as Leo II, with Zeno as regent. When Leo II died later that year, Zeno became emperor. The end of the Western Empire is sometimes dated to 476, early in Zeno's reign, when the Germanic Roman general Odoacer deposed the titular Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time ...

, but declined to replace him with another puppet.

To recover Italy, Zeno could only negotiate with the

To recover Italy, Zeno could only negotiate with the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

of Theodoric, who had settled in Moesia. He sent the gothic king to Italy as ''magister militum per Italiam'' ("commander in chief for Italy"). After the fall of Odoacer in 493, Theodoric, who had lived in Constantinople during his youth, ruled Italy on his own. Thus, by suggesting that Theodoric conquer Italy as his Ostrogothic kingdom, Zeno maintained at least a nominal supremacy in that western land while ridding the Eastern Empire of an unruly subordinate.Basiliscus

Basiliscus ( grc-gre, Βασιλίσκος, Basilískos; died 476/477) was Eastern Roman emperor from 9 January 475 to August 476. He became in 464, under his brother-in-law, Emperor Leo (457–474). Basiliscus commanded the army for an inva ...

, the general who led Leo I's 468 invasion of North Africa, but he recovered the throne twenty months later. However, he faced a new threat from another Isaurian, Leontius

Leontius ( el, Λεόντιος, Leóntios; – 15 February 706), was Byzantine emperor from 695 to 698. Little is known of his early life, other than that he was born in Isauria in Asia Minor. He was given the title of ''patrikios'', and ma ...

, who was also elected rival emperor. In 491 Anastasius I, an aged civil officer of Roman origin, became emperor, but it was not until 498 that the forces of the new emperor effectively took the measure of Isaurian resistance.

Justinian I and his successors

Justinian I, who assumed the throne in 527, oversaw a period of Byzantine expansion into former Roman territories. Justinian, the son of an

Justinian I, who assumed the throne in 527, oversaw a period of Byzantine expansion into former Roman territories. Justinian, the son of an Illyro-Roman

Illyro-Roman is a term used in historiography and anthropological studies for the Romanized Illyrians within the ancient Roman provinces of Illyricum, Moesia, Pannonia and Dardania. The term 'Illyro-Roman' can also be used to describe the Roman ...

peasant, may already have exerted effective control during the reign of his uncle, Justin I

Justin I ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, ''Ioustînos''; 450 – 1 August 527) was the Eastern Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial ...

(518–527).[Evans]

Justinian (AD 527–565)

/ref> In 532, attempting to secure his eastern frontier, Justinian signed a peace treaty with Khosrau I of Persia

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

agreeing to pay a large annual tribute to the Sassinids. In the same year, Justinian survived a revolt in Constantinople (the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

) which ended with the death of (allegedly) thirty thousand rioters. This victory solidified Justinian's power.Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terr ...

to reclaim the former province of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

from the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

who had been in control since 429 with their capital at Carthage. Their success came with surprising ease, but it was not until 548 that the major local tribes were subdued.[.] In Ostrogothic Italy

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, ...

, the deaths of Theodoric, his nephew and heir Athalaric, and his daughter Amalasuntha

Amalasuintha (495 – 30 April 534/535) was a ruler of Ostrogothic Kingdom from 526 to 535. She ruled first as regent for her son and thereafter as queen on throne. A regent is "a person who governs a kingdom in the minority, absence, or disabili ...

had left her murderer, Theodahad

Theodahad, also known as Thiudahad ( la, Flavius Theodahatus , Theodahadus, Theodatus; 480 – December 536) was king of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536.

Early life

Born at in Tauresium, Theodahad was a nephew of Theodoric the Great throu ...

(r. 534–536), on the throne despite his weakened authority. In 535, a small Byzantine expedition to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

was met with easy success, but the Goths soon stiffened their resistance, and victory did not come until 540, when Belisarius captured Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the ca ...

, after successful sieges of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Rome.[; .] In 535–536, Pope Agapetus I

Pope Agapetus I (489/490 – 22 April 536) was the bishop of Rome from 13 May 535 to his death. His father, Gordianus, was a priest in Rome and he may have been related to two previous popes, Felix III and Gregory I.

In 536, Agapetus traveled ...

was sent to Constantinople by Theodahad in order to request the removal of Byzantine forces from Sicily, Dalmatia, and Italy. Although Agapetus failed in his mission to sign a peace with Justinian, he succeeded in having the Monophysite Patriarch Anthimus I of Constantinople

Anthimus I (? – after 536) was a Miaphysite patriarch of Constantinople from 535–536. He was the bishop or archbishop of Trebizond before accession to the Constantinople see. He was deposed by Pope Agapetus I for adhering to Monophysitism

...

denounced, despite empress Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses

* Theodora (wife of Justinian I) ( 500 – 548), saint by the Orthodox Church

* Theodora o ...

's support and protection.[; .]

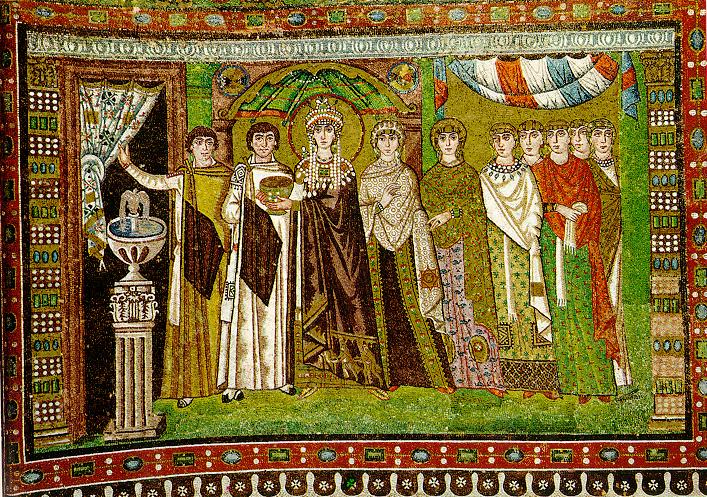

Nevertheless, the Ostrogoths were soon reunited under the command of

Nevertheless, the Ostrogoths were soon reunited under the command of Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War, recovering by 543 almost all the t ...

and captured Rome on 17 December 546; Belisarius was eventually recalled by Justinian in early 549.[Bury (1923)]

236–258

/ref> The arrival of the Armenian eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

Narses

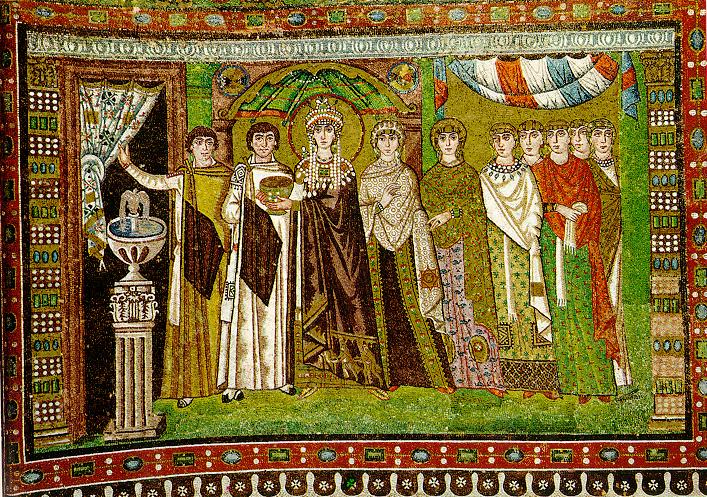

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

in Italy (late 551) with an army of some 35,000 men marked another shift in Gothic fortunes. Totila was defeated and died at the Battle of Busta Gallorum

At the Battle of Taginae (also known as the Battle of Busta Gallorum) in June/July 552, the forces of the Byzantine Empire under Narses broke the power of the Ostrogoths in Italy, and paved the way for the temporary Byzantine reconquest of the It ...

. His successor, Teia

Teia (died 552 or 553 AD), also known as Teja, Theia, Thila, Thela, and Teias, was the last Ostrogothic King of Italy. He led troops during the Battle of Busta Gallorum and had noncombatant Romans slaughtered in its aftermath. In late 552/early ...

, was likewise defeated at the Battle of Mons Lactarius

The Battle of Mons Lactarius (also known as Battle of the Vesuvius) took place in 552 or 553 AD during the Gothic War waged on behalf of Justinian I against the Ostrogoths in Italy.

After the Battle of Taginae, in which the Ostrogoth king Toti ...

(October 552). Despite continuing resistance from a few Goth garrisons and two subsequent invasions by the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

and Alamanni, the war for the Italian peninsula was at an end.[Bury (1923)]

259–281

/ref> In 551, a noble of Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hisp ...

, Athanagild

Athanagild ( 517 – December 567) was Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania. He had rebelled against his predecessor, Agila I, in 551. The armies of Agila and Athanagild met at Seville, where Agila met a second defeat. Following the death of ...

, sought Justinian's help in a rebellion against the king, and the emperor dispatched a force under Liberius, who, although elderly, proved himself a successful military commander. The Byzantine empire held on to a small slice of the Spania

Spania ( la, Provincia Spaniae) was a province of the Eastern Roman Empire from 552 until 624 in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. It was established by the Emperor Justinian I in an effort to restore the western prov ...

coast until the reign of Heraclius.[Bury (1923)]

286–288

/ref>

In the east, Roman–Persian Wars

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of conflicts between states of the Greco-Roman world and two successive Iranian empires: the Parthian and the Sasanian. Battles between the Parthian Empire and the ...

continued until 561 when Justinian's and Khusro's envoys agreed on a 50-year peace. By the mid-550s, Justinian had won victories in most theatres of operation, with the notable exception of the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, which were subjected to repeated incursions from the Slavs. In 559, the Empire faced a great invasion of Kutrigurs

Kutrigurs were Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished on the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the 6th century AD. To their east were the similar Utigurs and both possibly were closely related to the Bulgars. They warred with the Byzantine Empire an ...

and Sclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byz ...

. Justinian called Belisarius out of retirement, but once the immediate danger was over, the emperor took charge himself. The news that Justinian was reinforcing his Danube fleet made the Kutrigurs anxious, and they agreed to a treaty which gave them a subsidy and safe passage back across the river.[Vasiliev]

The Legislative Work of Justinian and Tribonian

/ref> In 529 a ten-man commission chaired by John the Cappadocian

John the Cappadocian ( el, Ἰωάννης ὁ Καππαδόκης) (''fl.'' 530s, living 548) was a praetorian prefect of the East (532–541) in the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). He was also a patrician and the '' ...

revised the ancient Roman legal code, creating the new ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

'', a collection of laws that came to be referred to as "Justinian's Code". In the ''Pandects

The ''Digest'', also known as the Pandects ( la, Digesta seu Pandectae, adapted from grc, πανδέκτης , "all-containing"), is a name given to a compendium or digest of juristic writings on Roman law compiled by order of the Byzantine e ...

'', completed under Tribonian

Tribonian ( Greek: Τριβωνιανός rivonia'nos c. 485?–542) was a notable Byzantine jurist and advisor, who during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I, supervised the revision of the legal code of the Byzantine Empire. He has been desc ...

's direction in 533, order and system were found in the contradictory rulings of the great Roman jurists, and a textbook, the '' Institutiones'', was issued to facilitate instruction in the law schools. The fourth book, the ''Novellae'', consisted of collections of imperial edicts promulgated between 534 and 565. Because of his ecclesiastical policies, Justinian came into collision with the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s, the pagans, and various Christian sects. The latter included the Manichaeans

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (AD ...

, the Nestorians

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian N ...

, the Monophysites

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incar ...

, and the Arians

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

. In order to completely eradicate paganism, Justinian closed the famous philosophic school in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

in 529.[Vasiliev]

The Ecclesiastical Policy of Justinian

/ref>

During the 6th century, the traditional

During the 6th century, the traditional Greco-Roman culture

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

was still influential in the Eastern empire with prominent representatives such as the natural philosopher John Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tr ...

. Nevertheless, the Christian philosophy and culture were in the ascendant and began to dominate the older culture. Hymns written by Romanos the Melode marked the development of the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of ...

, while architects and builders worked to complete the new Church of the Holy Wisdom

Holy Wisdom (Greek: , la, Sancta Sapientia, russian: Святая София Премудрость Божия, translit=Svyataya Sofiya Premudrost' Bozhiya "Holy Sophia, Divine Wisdom") is a concept in Christian theology.

Christian theology ...

, Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

, designed to replace an older church destroyed in the course of the Nika revolt. Hagia Sophia stands today as one of the major monuments of architectural history.Justin II

Justin II ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, Ioustînos; died 5 October 578) or Justin the Younger ( la, Iustinus minor) was Eastern Roman Emperor from 565 until 578. He was the nephew of Justinian I and the husband of Sophia, the ...

refused to pay the large tribute to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

invaded Italy; by the end of the century only a third of Italy was in Byzantine hands. Justin's successor, Tiberius II

Tiberius II Constantine ( grc-gre, Τιβέριος Κωνσταντῖνος, Tiberios Konstantinos; died 14 August 582) was Eastern Roman emperor from 574 to 582. Tiberius rose to power in 574 when Justin II, prior to a mental breakdown, procl ...

, choosing between his enemies, awarded subsidies to the Avars while taking military action against the Persians. Though Tiberius' general, Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

, led an effective campaign on the eastern frontier, subsidies failed to restrain the Avars. They captured the Balkan fortress of Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyrian ...

in 582, while the Slavs began to make inroads across the Danube. Maurice, who meanwhile succeeded Tiberius, intervened in a Persian civil war, placed the legitimate Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

back on the throne and married his daughter to him. Maurice's treaty with his new brother-in-law enlarged the territories of the Empire to the East and allowed the energetic Emperor to focus on the Balkans. By 602 a series of successful Byzantine campaigns had pushed the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube.

Heraclian dynasty and shrinking borders

After Maurice's murder by Phocas

Phocas ( la, Focas; grc-gre, Φωκάς, Phōkás; 5475 October 610) was Eastern Roman emperor from 602 to 610. Initially, a middle-ranking officer in the Eastern Roman army, Phocas rose to prominence as a spokesman for dissatisfied soldiers ...

, Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the Roman province of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

. Phocas, an unpopular ruler who is invariably described in Byzantine sources as a "tyrant", was the target of a number of senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

with an icon affixed to the prow of his ship. Following the ascension of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into Asia Minor, also occupying Damascus and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and removing the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

to Ctesiphon. The counter-offensive of Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an acheiropoietos

''Acheiropoieta'' (Medieval Greek: , "made without hand"; singular ''acheiropoieton'') — also called icons made without hands (and variants) — are Christianity, Christian icons which are said to have come into existence miraculously; not crea ...

image of Christ was carried as a military standard. Similarly, when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626, the victory was attributed to the icons of the Virgin which were led in procession by Patriarch Sergius about the walls of the city. The main Sassanid force was destroyed at Nineveh in 627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. The war had exhausted both the Byzantine and Sassanid Empire, and left them extremely vulnerable to the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

forces which emerged in the following years. The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Yarmuk

The Battle of the Yarmuk (also spelled Yarmouk) was a major battle between the army of the Byzantine Empire and the Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements that lasted for six days in August 63 ...

in 636, and Ctesiphon fell in 634.

In an attempt to heal the doctrinal divide between Chalcedonian and monophysite Christians, Heraclius proposed monotheletism

Monothelitism, or monotheletism (from el, μονοθελητισμός, monothelētismós, doctrine of one will), is a theological doctrine in Christianity, that holds Christ as having only one will. The doctrine is thus contrary to dyothelit ...

as a compromise. In 638 the new doctrine was posted in the narthex of Hagia Sophia as part of a text called the ''Ekthesis'', which also forbade further discussion of the issue. By this time, however, Syria and Palestine, both hotbeds of monophysite belief, had fallen to the Arabs, and another monophysite center, Egypt, fell by 642. Ambivalence toward Byzantine rule on the part of monophysites may have lessened local resistance to the Arab expansion.

Heraclius did succeed in establishing a dynasty, and his descendants held onto the throne, with some interruption, until 711. Their reigns were marked both by major external threats, from the west and the east, which reduced the territory of the empire to a fraction of its 6th-century extent, and by significant internal turmoil and cultural transformation.

The Arabs, now firmly in control of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in 674–678 laid siege to Constantinople itself. The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, and a thirty-years' truce was signed between the Empire and the

Heraclius did succeed in establishing a dynasty, and his descendants held onto the throne, with some interruption, until 711. Their reigns were marked both by major external threats, from the west and the east, which reduced the territory of the empire to a fraction of its 6th-century extent, and by significant internal turmoil and cultural transformation.

The Arabs, now firmly in control of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in 674–678 laid siege to Constantinople itself. The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, and a thirty-years' truce was signed between the Empire and the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

. However, the Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

n raids continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the old city walls, or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses. Constantinople itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centers, it was partly ruralised. The city also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased. The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions was filled by the theme system, which entailed the division of Asia Minor into "provinces" occupied by distinct armies which assumed civil authority and answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its roots in certain ''ad hoc'' measures taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an entirely new system of imperial governance.

The withdrawal of massive numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Anatolia, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements. In the 670s the Bulgars were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the

The withdrawal of massive numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Anatolia, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements. In the 670s the Bulgars were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

, and in 680 Byzantine forces which had been sent to disperse these new settlements were defeated. In the next year Constantine IV

Constantine IV ( la, Constantinus; grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantînos; 650–685), called the Younger ( la, iunior; grc-gre, ὁ νέος, ho néos) and sometimes incorrectly the Bearded ( la, Pogonatus; grc-gre, Πωγων ...

signed a treaty with the Bulgar khan Asparukh

Asparuh (also ''Ispor''; bg, Аспарух, Asparuh or (rarely) bg, Исперих, Isperih) was а ruler of Bulgars in the second half of the 7th century and is credited with the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empire in 681.

Early life

...

, and the new Bulgarian state assumed sovereignty over a number of Slavic tribes which had previously, at least in name, recognized Byzantine rule. In 687–688, the emperor Justinian II

Justinian II ( la, Iustinianus; gr, Ἰουστινιανός, Ioustinianós; 668/69 – 4 November 711), nicknamed "the Slit-Nosed" ( la, Rhinotmetus; gr, ὁ Ῥινότμητος, ho Rhinótmētos), was the last Eastern Roman emperor of the ...

led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgars which made significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

to Macedonia demonstrates the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.

The one Byzantine city that remained relatively unaffected, despite a significant drop in population and at least two outbreaks of the plague, was Constantinople. However, the imperial capital was marked by its own variety of conflict, both political and religious. Constans II continued the monothelite policy of his grandfather, Heraclius, meeting with significant opposition from laity and clergy alike. The most vocal opponents, Maximus the Confessor

Maximus the Confessor ( el, Μάξιμος ὁ Ὁμολογητής), also spelt Maximos, otherwise known as Maximus the Theologian and Maximus of Constantinople ( – 13 August 662), was a Christian monk, theologian, and scholar.

In his ear ...

and Pope Martin I

Pope Martin I ( la, Martinus I, el, Πάπας Μαρτίνος; between 590 and 600 – 16 September 655), also known as Martin the Confessor, was the bishop of Rome from 21 July 649 to his death 16 September 655. He served as Pope Theodore I's ...

were arrested, brought to Constantinople, tried, tortured, and exiled. Constans seems to have become immensely unpopular in the capital, and moved his residence to Syracuse, Sicily, where he was ultimately murdered by a member of his court. The Senate experienced a revival in importance in the seventh century and clashed with the emperors on numerous occasions. The final Heraclian emperor, Justinian II

Justinian II ( la, Iustinianus; gr, Ἰουστινιανός, Ioustinianós; 668/69 – 4 November 711), nicknamed "the Slit-Nosed" ( la, Rhinotmetus; gr, ὁ Ῥινότμητος, ho Rhinótmētos), was the last Eastern Roman emperor of the ...

, attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through severe taxation and the appointment of "outsiders" to administrative posts. He was driven from power in 695, and took shelter first with the Khazars and then with the Bulgars. In 705 he returned to Constantinople with the armies of the Bulgar khan Tervel

Khan Tervel ( bg, Тервел) also called ''Tarvel'', or ''Terval'', or ''Terbelis'' in some Byzantine sources, was the khan of Bulgaria during the First Bulgarian Empire at the beginning of the 8th century. In 705 Emperor Justinian II named ...

, retook the throne, and instituted a reign of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711, supported once more by the urban aristocracy, the Heraclian dynasty came to an end.

The 7th century was a period of radical transformation. The empire which had once stretched from Spain to Jerusalem was now reduced to Anatolia, Chersonesos

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

, and some fragments of Italy and the Balkans. The territorial losses were accompanied by a cultural shift; urban civilization was massively disrupted, classical literary genres were abandoned in favor of theological treatises, and a new "radically abstract" style emerged in the visual arts. That the empire survived this period at all is somewhat surprising, especially given the total collapse of the Sassanid Empire in the face of the Arab expansion, but a remarkably coherent military reorganization helped to withstand the exterior pressures and laid the groundwork for the gains of the following dynasty. However, the massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire consequent on the loss of territory in the seventh century has been said to have caused a decisive break in east Mediterranean ''Romanness'' and that the Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor state rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.

There also seem to have been interactions between the Byzantine realm and China at this time. Byzantine Greek historian

There also seem to have been interactions between the Byzantine realm and China at this time. Byzantine Greek historian Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

stated that two Nestorian Christian monks eventually uncovered how silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

was made. From this revelation monks were sent by Justinian I as spies on the Silk Road from Constantinople to China and back to steal the silkworm eggs. This resulted in silk production in the Mediterranean, particularly in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, in northern Greece,[LIVUS (28 October 2010)]

"Silk Road"

''Articles of Ancient History''. Retrieved on 22 September 2016. and giving the Byzantine Empire a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe until the loss of its territories in Southern Italy. The Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as the last historian o ...

, writing during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), relayed information about China's geography, its capital city ''Khubdan'' (Old Turkic

Old Turkic (also East Old Turkic, Orkhon Turkic language, Old Uyghur) is the earliest attested form of the Turkic languages, found in Göktürk and Uyghur Khaganate inscriptions dating from about the eighth to the 13th century. It is the old ...

: ''Khumdan'', i.e. Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin S ...

), its current ruler ''Taisson'' whose name meant " Son of God" (Chinese: ''Tianzi'', although this could be derived from the name of Emperor Taizong of Tang

Emperor Taizong of Tang (28January 59810July 649), previously Prince of Qin, personal name Li Shimin, was the second emperor of the Tang dynasty of China, ruling from 626 to 649. He is traditionally regarded as a co-founder of the dynasty ...

), and correctly pointed to its reunification by the Sui Dynasty (581–618) as occurring during the reign of Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

, noting that China had previously been divided politically along the Yangzi River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

by two warring nations. This seems to match the conquest of the Chen dynasty in southern China by Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604). The Chinese '' Old Book of Tang'' and '' New Book of Tang'' mention several embassies made by ''Fu lin'' (拂菻; i.e. Byzantium), which they equated with Daqin

Daqin (; alternative transliterations include Tachin, Tai-Ch'in) is the ancient Chinese name for the Roman Empire or, depending on context, the Near East, especially Syria. It literally means "great Qin"; Qin () being the name of the founding dyn ...

(i.e. the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

), beginning in 643 with an embassy sent by the king ''Boduoli'' (波多力, i.e. Constans II Pogonatos) to Emperor Taizong of Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

, bearing gifts such as red glass.[Hirth (2000) ]885

Year 885 ( DCCCLXXXV) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* Summer – Emperor Charles the Fat summons a meeting of officials at Lobith (moder ...

br>''East Asian History Sourcebook''

Retrieved 2016-09-22. These histories also provided cursory descriptions of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, its walls, and how it was besieged by ''Da shi'' (大食; the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

) and their commander "Mo-yi" (摩拽伐之; i.e. Muawiyah I, governor of Syria before becoming caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

), who forced them to pay tribute.Henry Yule

Sir Henry Yule (1 May 1820 – 30 December 1889) was a Scottish Orientalist and geographer. He published many travel books, including translations of the work of Marco Polo and ''Mirabilia'' by the 14th-century Dominican Friar Jordanus. ...

highlights the fact that Yazdegerd III

Yazdegerd III (also spelled Yazdgerd III and Yazdgird III; pal, 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩) was the last Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 632 to 651. His father was Shahriyar and his grandfather was Khosrow II.

Ascending the throne at the ...

(r. 632–651), last ruler of the Sasanian Empire, sent diplomats to China for securing aid from Emperor Taizong ( considered the suzerain over Ferghana in Central Asia) during the loss of the Persian heartland to the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate, which may have also prompted the Byzantines to send envoys to China amid their recent loss of Syria to the Muslims. Tang Chinese sources also recorded how Sassanid prince Peroz III

Peroz III ( pal, 𐭯𐭩𐭫𐭥𐭰 ''Pērōz''; ) was son of Yazdegerd III, the last Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. After the death of his father, who legend says was killed by a miller at the instigation of the governor of Marw, he retreated ...

(636–679) fled to Tang China following the conquest of Persia by the growing Islamic caliphate. Other Byzantine embassies in Tang China are recorded as arriving in 711, 719, and 742.Michael VII Doukas

Michael VII Doukas or Ducas ( gr, Μιχαήλ Δούκας), nicknamed Parapinakes ( gr, Παραπινάκης, lit. "minus a quarter", with reference to the devaluation of the Byzantine currency under his rule), was the senior Byzantine e ...

(Mie li sha ling kai sa 滅力沙靈改撒) of ''Fu lin'' dispatched a diplomatic mission to China's Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

that arrived in 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song

Emperor Shenzong of Song (25 May 1048 – 1 April 1085), personal name Zhao Xu, was the sixth emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Zhongzhen but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after his coronation. He reigned f ...

.[Sezgin et al. (1996), p. 25.]

The period of internal instability

Isaurian dynasty and Iconoclasm

Leo III the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian ( gr, Λέων ὁ Ἴσαυρος, Leōn ho Isauros; la, Leo Isaurus; 685 – 18 June 741), also known as the Syrian, was Byzantine Emperor from 717 until his death in 741 and founder of the Isaurian dynasty. He put an e ...

(717–741 AD) turned back the Muslim assault in 718, and achieved victory with the major help of the Bulgarian khan Tervel, who killed 32,000 Arabs with his army in 740 in Akroinon. Raids by the Arabs against Byzantium would plague the Empire all during the reign of Leo III. However, the threat against the Empire from the Arabs would never again be as great as it was during this first attack of Leo's reign.[John Julius Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', p. 353.] In just over twelve years, Leo the Isaurian had raised himself from being a mere Syrian peasant to being the Emperor of Byzantium.Chalke Gate

The Chalke Gate ( el, ), was the main ceremonial entrance (vestibule) to the Great Palace of Constantinople in the Byzantine period. The name, which means "the Bronze Gate", was given to it either because of the bronze portals or from the gilde ...

or vestibule to the Great Palace of Byzantium. "Chalke" means bronze in the Greek language and the Chalke Gate derived its name from the great bronze doors that formed the ceremonial entrance to the Great Palace.

Built in reign of Anastasius I (491–518 AD), the Chalke Gates were meant to celebrate the Byzantium victory in the Isaurian War The Isaurian War was a conflict that lasted from 492 to 497 and that was fought between the army of the Eastern Roman Empire and the rebels of Isauria. At the end of the war, Eastern Emperor Anastasius I regained control of the Isauria region and t ...

of 492–497 AD. The Chalke Gates had been destroyed in the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

of 532 AD.[John Julius Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', p. 355.] When the gates were rebuilt again by Justinian I (527–565 AD) and his wife Theodora, a large golden statue of Christ was positioned over the doors. At the beginning of the eighth century (the 700s AD) there arose a feeling among some people of Byzantine Empire that religious statues and religious paintings that decorated churches were becoming the object of worship in and of themselves rather that the worship of God. Thus, the images, or icons, were interfering with the true goal of worship. Thus, an "iconoclast

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

" movement arose which sought to "cleanse" the church by destroying all religions icons. The primary icon of all Byzantium was the golden Christ over the Chalke Gates. Iconoclasm was more popular among people of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

as rather than the European portion of the Byzantine Empire. Although, Leo III was Syrian, there is no evidence that he was given to tendencies toward iconoclasm.Constantine V

Constantine V ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos; la, Constantinus; July 718 – 14 September 775), was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able ...

. Indeed, Constantine V's iconoclastic policies caused a revolt led by the iconodule

Iconodulism (also iconoduly or iconodulia) designates the religious service to icons (kissing and honourable veneration, incense, and candlelight). The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (''eikonodoulos'') (from el, ε ...

Artabasdus in 742 AD. Artabasdus (742 AD) actually overthrew Constantine V and ruled as Emperor for a few months before Constantine V was restored to power.

Leo III's son, Constantine V

Constantine V ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos; la, Constantinus; July 718 – 14 September 775), was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able ...

(741–775 AD), won noteworthy victories in northern Syria, and also thoroughly undermined Bulgar strength during his reign. Like his father, Constantine V, Leo IV (775–780 AD) was an iconoclast.[John Julius Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Apogee'', p. 2.] However, Leo IV was dominated by his wife Irene who tended toward iconodulism and supported religious statues and images. Upon the death of Leo IV in 780 AD, his 10-year-old son, Constantine VI (780–797 AD) succeeded to the Byzantine throne under the regency of his mother Irene. However, before Constantine VI could come of age and rule in his own right, his mother usurped the throne for herself.emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of Melitene. Under the leadership of Krum

Krum ( bg, Крум, el, Κροῦμος/Kroumos), often referred to as Krum the Fearsome ( bg, Крум Страшни) was the Khan of Bulgaria from sometime between 796 and 803 until his death in 814. During his reign the Bulgarian territory ...

the Bulgar threat also reemerged, but in 814 Krum's son, Omortag, arranged a peace with the Byzantine Empire.

* Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

. Also as noted above, Icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most ...

s were banned by Leo and Constantine, leading to revolts by iconodule

Iconodulism (also iconoduly or iconodulia) designates the religious service to icons (kissing and honourable veneration, incense, and candlelight). The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (''eikonodoulos'') (from el, ε ...

s (supporters of icons) throughout the empire. After the efforts of Empress Irene, the Second Council of Nicaea

The Second Council of Nicaea is recognized as the last of the first seven ecumenical councils by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. In addition, it is also recognized as such by the Old Catholics, the Anglican Communion, an ...

met in 787, and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshiped.

Irene made determined efforts to stamp out iconoclasm everywhere in the Empire including within the ranks of the army. During Irene's reign the Arabs were continuing to raid into and despoil the small farms of the Anatolian section of the Empire. These small farmers of Anatolia owed a military obligation to the Byzantine throne. Indeed, the Byzantine army and the defense of the Empire was largely based on this obligation and the Anatolian farmers. The iconodule policy drove these farmers out of the army and thus off their farms. Thus, the army was weakened and was unable to protect Anatolia from the Arab raids.[John Julius Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Apogee'', p. 4.] Many of the remaining farmers of Anatolia were driven from the farm to settle in the city of Byzantium, thus, further reducing the army's ability to raise soldiers. Additionally, the abandoned farms fell from the tax rolls and reduced the amount of income that government received. These farms were taken over by the largest land owner in the Byzantine Empire—the monasteries. To make the situation even worse, Irene had exempted all monasteries from all taxation.

Given the financial ruin into which the Empire was headed, it was no wonder, then, that Irene was, eventually, deposed by her own Logothete Logothete ( el, λογοθέτης, ''logothétēs'', pl. λογοθέται, ''logothétai''; Med. la, logotheta, pl. ''logothetae''; bg, логотет; it, logoteta; ro, logofăt; sr, логотет, ''logotet'') was an administrative title ...

of the Treasury. The leader of this successful revolt against Irene replaced her on the Byzantine throne under the name Nicephorus I

Nikephoros I or Nicephorus I ( gr, Νικηφόρος; 750 – 26 July 811) was Byzantine emperor from 802 to 811. Having served Empress Irene as '' genikos logothetēs'', he subsequently ousted her from power and took the throne himself. In r ...

.Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

, but, according to Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking ...

, the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, one of her favourites.

Amorian (Phrygian) dynasty

In 813 Leo V the Armenian

Leo V the Armenian ( gr, Λέων ὁ ἐξ Ἀρμενίας, ''Leōn ho ex Armenias''; 775 – 25 December 820) was the Byzantine emperor from 813 to 820. A senior general, he forced his predecessor, Michael I Rangabe, to abdicate and assumed ...

(813–820 AD) restored the policy of iconoclasm. This started the period of history called the "Second Iconclasm" which would last from 813 until 842 AD. Only in 843, would Empress Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses