History of the Communist Party USA on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first socialist political party in the United States was the

The first socialist political party in the United States was the

From its inception, the

From its inception, the

Now that the above ground element was legal, the Communists decided that their central task was to develop roots within the

Now that the above ground element was legal, the Communists decided that their central task was to develop roots within the

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

(CPUSA) is an American political party with a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

platform that was founded in 1919 in Chicago. The history of the Communist Party USA is deeply rooted in the history of the American labor movement and the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

indeed played critical roles in the earliest struggles to organize American workers into unions as well as the later civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and anti-war movement

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to ...

s. The history of CPUSA is ideologically complex and tied to communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, labor movements

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

, and Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

. Many party members were forced to work covertly due to the high level of political repression in the United States against Communists. CPUSA faced many challenges in gaining a foothold in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

as they endured two eras of the Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

and never experienced significant electoral success. Despite struggling to become a major electoral player, CPUSA was the most prominent leftist party in the United States. CPUSA developed close ties with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, which led to them being financially linked.

Membership of the CPUSA peaked in the late 1940s, with over 75,000 members in 1947. But their influence spanned beyond just their membership as some candidates in national elections garnered over 100,000 votes. However, the CPUSA began to decline in membership in the late 1940s and into the 1950s, presumably due to the Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

where the US government publicly tried and convicted Communists and CPUSA members on the grounds of the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

. CPUSA faced challenges when the Dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

took place, as they lost their main source of funding. The Communist Party USA is still alive today but its membership and activity have shifted to a more online medium. Despite staying active through various challenges, including a significant fracturing in the 1990s, they have never managed to reach their previous heights.

History

1919–1921: Formation and early history

The first socialist political party in the United States was the

The first socialist political party in the United States was the Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

(SLP), formed in 1876 and for many years a viable force in the international socialist movement. By the mid-1890s, the SLP came under the influence of Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regarded as the forefather o ...

and his radical views led to widespread discontent amongst the members, leading to the formation of the reformist-oriented Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

(SPA) around the turn of the 20th century. A left-wing gradually emerged within the Socialist Party, much to the consternation of many party leaders. The new Left wing of the SPA attempted to win a majority of executive positions within the party's internal elections, after the election results, in which the Left wing of the party succeeded in electing many candidates, moderate leadership subsequently invalidated the 1919 elections. This flouting of democracy within the party set the stage for factions to split off to begin forming a new Communist Party.

In January 1919, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

invited the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party

The Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party was an organized faction within the Socialist Party of America in 1919 which served as the core of the dual communist parties which emerged in the fall of that year—the Communist Party of America a ...

to join the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

(Comintern). During the spring of 1919, the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party, buoyed by a large influx of new members from countries involved in the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, prepared to wrest control from the smaller controlling faction of moderate socialists. A referendum to join Comintern passed with 90% support, but the incumbent leadership suppressed the results. Elections for the party's National Executive Committee resulted in 12 leftists being elected out of a total of 15. Calls were made to expel moderates from the party. The moderate incumbents struck back by expelling several state organizations, half a dozen language federations and many locals in all two-thirds of the membership.

The Socialist Party then called an emergency convention on August 30, 1919. The party's Left Wing Section made plans at a June conference of its own to regain control of the party by sending delegations from the sections of the party that had been expelled to the convention to demand that they be seated. However, the language federations, eventually joined by C. E. Ruthenberg

Charles Emil Ruthenberg (July 9, 1882 – March 1, 1927) was an American Marxist politician and a founder and head of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

Biography

Early years

Charles Emil Ruthenberg was born July 9, 1882, in Cleveland, Ohio, ...

and Louis C. Fraina

Louis C. Fraina (October 7, 1892 – September 15, 1953) was a founding member of the Communist Party USA in 1919. After running afoul of the Communist International in 1921 over the alleged misappropriation of funds, Fraina left the organized ra ...

, turned away from that effort and formed their own party, the Communist Party of America at a separate convention on September 1, 1919. Meanwhile, plans led by John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow

Benjamin Gitlow (December 22, 1891 – July 19, 1965) was a prominent American socialist politician of the early 20th century and a founding member of the Communist Party USA. During the end of the 1930s, Gitlow turned to conservatism and wrote t ...

to crash the Socialist Party Convention went ahead. Tipped off, the incumbents called the police, who obligingly expelled the leftists from the hall. The remaining leftist delegates walked out and meeting with the expelled delegates formed the Communist Labor Party on August 30, 1919.

The Comintern was not happy with two communist parties and in January 1920 dispatched an order that the two parties, which consisted of about 12,000 members, merge under the name United Communist Party and to follow the party line established in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. Part of the Communist Party of America under the leadership of Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Centr ...

did this, but a faction

Faction or factionalism may refer to:

Politics

* Political faction, a group of people with a common political purpose

* Free and Independent Faction, a Romanian political party

* Faction (''Planescape''), a political faction in the game ''Planes ...

under the leadership of Nicholas I. Hourwich and Alexander Bittelman

Alexander "Alex" Bittelman (1890–1982) was a Russian-born Jewish-American communist political activist, Marxist theorist, influential theoretician of the Communist Party USA and writer. A founding member, Bittelman is best remembered as the chi ...

continued to operate independently as the Communist Party of America. A more strongly worded directive from the Comintern eventually did the trick and the parties were merged in May 1921. Only five percent of the members of the newly formed party were native English-speakers. Many of the members came from the ranks of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

(IWW).Buhle, ''Marxism in the USA: From 1870 to the Present Day'' (1987)

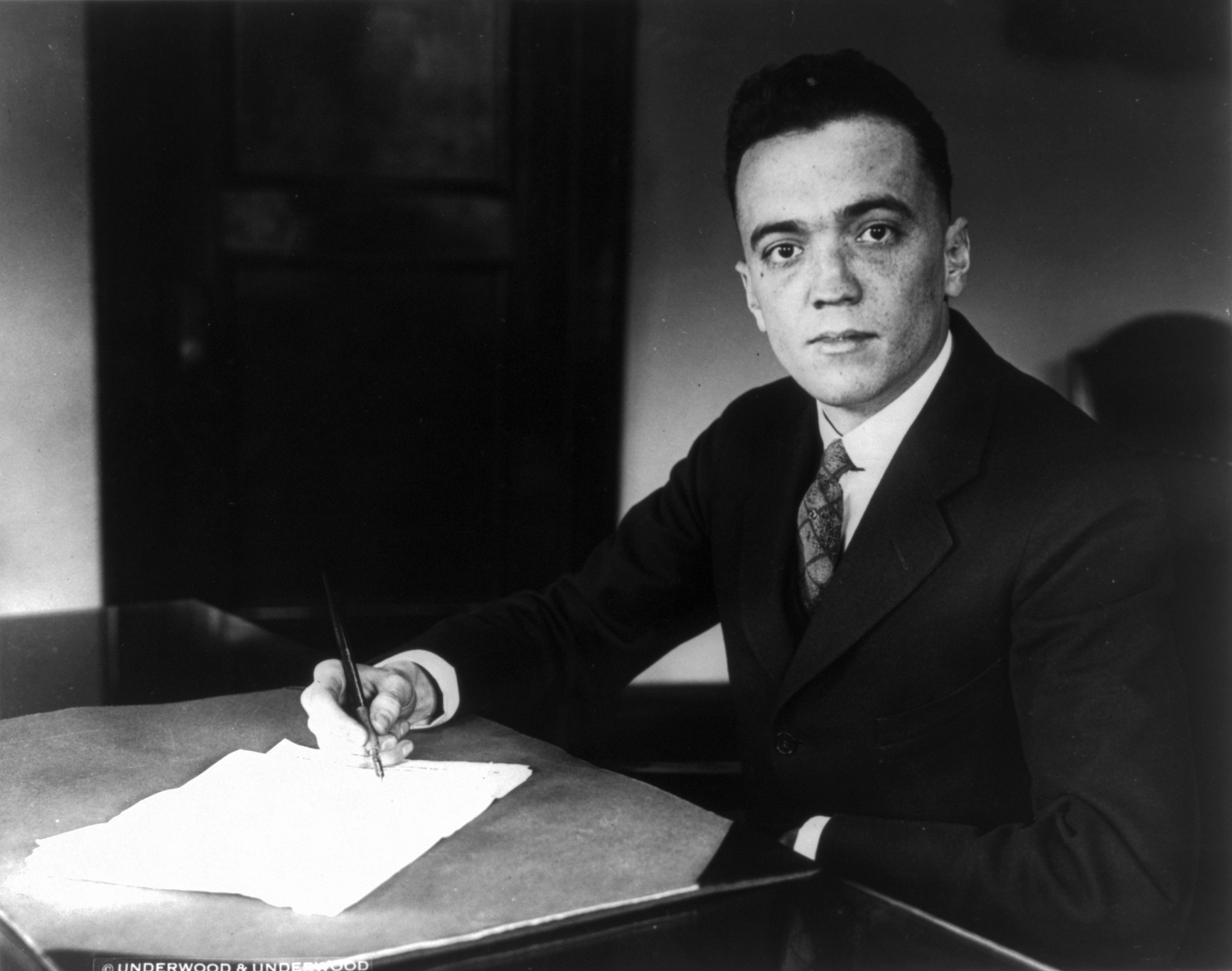

1919–1923: Red Scare and the Communist Party USA

From its inception, the

From its inception, the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

(CPUSA) came under attack from state and federal governments and later the U.S. Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

's Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

. In 1919, after a series of unattributed bombings and attempted assassinations of government officials and judges (later traced to militant adherents of the radical anarchist Luigi Galleani), the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

headed by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936), was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scare ...

, acting under the Sedition Act of 1918

The Sedition Act of 1918 () was an Act of the United States Congress that extended the Espionage Act of 1917 to cover a broader range of offenses, notably speech and the expression of opinion that cast the government or the war effort in a neg ...

, began arresting thousands of foreign-born party members, many of whom the government deported. The Communist Party was forced underground and took to the use of pseudonyms and secret meetings in an effort to evade the authorities.

The party apparatus was to a great extent underground. It re-emerged in the last days of 1921 as a legal political party called the Workers Party of America

The Workers Party of America (WPA) was the name of the legal party organization used by the Communist Party USA from the last days of 1921 until the middle of 1929.

Background

As a legal political party, the Workers Party accepted affiliation fr ...

(WPA). As the Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

and deportations of the early 1920s ebbed, the party became bolder and more open. However, an element of the party remained permanently underground and came to be known as the "CPUSA secret apparatus". During this time, immigrants from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

are said to have played a very prominent role in the Communist Party.Klehr, Harvey. ''Communist Cadre: The Social Background of the American Communist Party Elite''. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press. A majority of the members of the Socialist Party were immigrants and an "overwhelming" percentage of the Communist Party consisted of recent immigrants.Glazer, Nathan ''The Social Basis of American Communism.''

1923–1929: Factional war

Now that the above ground element was legal, the Communists decided that their central task was to develop roots within the

Now that the above ground element was legal, the Communists decided that their central task was to develop roots within the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

. This move away from hopes of revolution in the near future to a more nuanced approach was accelerated by the decisions of the Fifth World Congress of the Comintern held in 1925. The Fifth World Congress decided that the period between 1917 and 1924 had been one of revolutionary upsurge, but that the new period was marked by the stabilization of capitalism and that revolutionary attempts in the near future were to be stopped. The American Communists embarked then on the arduous work of locating and winning allies.

That work was complicated by factional struggles within the Communist Party which quickly developed a number of more or less fixed factional groupings within its leadership: a faction around the party's Executive Secretary C. E. Ruthenberg, which was largely organized by his supporter Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Centr ...

; and the Foster-Cannon faction, headed by William Z. Foster, who headed the party's Trade Union Educational League

The Trade Union Educational League (TUEL) was established by William Z. Foster in 1920 (through 1928) as a means of uniting radicals within various trade unions for a common plan of action. The group was subsidized by the Communist International ...

(TUEL); and James P. Cannon, who led the International Labor Defense (ILD) organization.

Foster, who had been deeply involved in the Steel strike of 1919 and had been a long-time syndicalist

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of pr ...

and a Wobbly

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

, had strong bonds with the progressive leaders of the Chicago Federation of Labor

The Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) is an umbrella organization for unions in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It is a subordinate body of the AFL–CIO, and as of 2011 has about 320 affiliated member unions representing half a million union members in C ...

(CFL) and through them with the Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

and nascent farmer-labor parties. Under pressure from the Comintern, the party broke off relations with both groups in 1924. In 1925, the Comintern through its representative Sergei Gusev ordered the majority Foster faction to surrender control to Ruthenberg's faction, which Foster complied. However, the factional infighting within the Communist Party did not end as the Communist leadership of the New York locals of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), whose members were employed in the women's clothing industry, was once one of the largest labor unions in the United States, one of the first U.S. unions to have a primarily female membe ...

(ILGWU) lost the 1926 strike of cloakmakers in New York City in large part because of intra-party factional rivalries.

Ruthenberg died in 1927 and his ally Lovestone succeeded him as party secretary. Cannon attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928 hoping to use his connections with leading circles within it to regain the advantage against the Lovestone faction, but Cannon and Maurice Spector

Maurice Spector (March 19, 1898 – August 1, 1968) was a Canadian politician who served as the chairman of the Communist Party of Canada and the editor of its newspaper, '' The Worker'', for much of the 1920s. He was an early follower of Leon Tro ...

of the Communist Party of Canada

The Communist Party of Canada (french: Parti communiste du Canada) is a federal political party in Canada, founded in 1921 under conditions of illegality. Although it does not currently have any parliamentary representation, the party's can ...

(CPC) were accidentally given a copy of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

's "Critique of the Draft Program of the Comintern" that they were instructed to read and return. Persuaded by its contents, they came to an agreement to return to the United States and campaign for the document's positions. A copy of the document was then smuggled out of the country in a child's toy. Back in the United States, Cannon and his close associates in the ILD such as Max Shachtman

Max Shachtman (; September 10, 1904 – November 4, 1972) was an American Marxist theorist. He went from being an associate of Leon Trotsky to a social democrat and mentor of senior assistants to AFL–CIO President George Meany.

Beginnings

S ...

and Martin Abern Martin may refer to:

Places

* Martin City (disambiguation)

* Martin County (disambiguation)

* Martin Township (disambiguation)

Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Austral ...

, dubbed the "three generals without an army", began to organize support for Trotsky's theses. However, as this attempt to develop a Left Opposition

The Left Opposition was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (b) from 1923 to 1927 headed ''de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. The Left Opposition formed as part of the power struggle within the party leadership that began with the Soviet fou ...

came to light, they and their supporters were expelled. Cannon and his followers organized the Communist League of America

The Communist League of America (Opposition) was founded by James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman and Martin Abern late in 1928 after their expulsion from the Communist Party USA for Trotskyism. The CLA(O) was the United States section of Leon Trotsky's I ...

(CLA) as a section of Trotsky's International Left Opposition

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

(ILO).

At the same Congress, Lovestone had impressed the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

(CPSU) as a strong supporter of Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

, the general secretary of the Comintern. This was to have unfortunate consequences for Lovestone as in 1929 Bukharin was on the losing end of a struggle with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

and was purged from his position on the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

and removed as head of the Comintern. In a reversal of the events of 1925, a Comintern delegation sent to the United States demanded that Lovestone resign as party secretary in favor of his archrival Foster despite the fact that Lovestone enjoyed the support of the vast majority of the American party's membership. Lovestone traveled to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and appealed directly to the Comintern. Stalin informed Lovestone that he "had a majority because the American Communist Party until now regarded you as the determined supporter of the Communist International. And it was only because the Party regarded you as friends of the Comintern that you had a majority in the ranks of the American Communist Party".

When Lovestone returned to the United States, he and his ally Benjamin Gitlow

Benjamin Gitlow (December 22, 1891 – July 19, 1965) was a prominent American socialist politician of the early 20th century and a founding member of the Communist Party USA. During the end of the 1930s, Gitlow turned to conservatism and wrote t ...

were purged despite holding the leadership of the party. Ostensibly, this was not due to Lovestone's insubordination in challenging a decision by Stalin, but for his support for American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is inherently different from other nations.Communist Party (Opposition), a section of the pro-Bukharin

The upheavals within the Communist Party in 1928 were an echo of a much more significant change as Stalin's decision to break off any form of collaboration with Western socialist parties, which were now condemned as "

The upheavals within the Communist Party in 1928 were an echo of a much more significant change as Stalin's decision to break off any form of collaboration with Western socialist parties, which were now condemned as "

The ideological rigidity of the third period began to crack with two events: the election of

The ideological rigidity of the third period began to crack with two events: the election of

The Communist Party was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. Although membership in the party rose to about 66,000 by 1939, nearly 20,000 members left the party by 1943, after the Soviet Union signed the

The Communist Party was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. Although membership in the party rose to about 66,000 by 1939, nearly 20,000 members left the party by 1943, after the Soviet Union signed the

More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the Communist Party with the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. The

More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the Communist Party with the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. The

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary and the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Secret Speech of Nikita Khrushchev to the CPSU listing a devastatingly long and detailed list of atrocities committed by and in the name of Joseph Stalin had a cataclysmic effect on the previously Stalinism, Stalinist majority membership Communist Party. Membership plummeted and the leadership briefly faced a challenge from a loose grouping led by ''

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary and the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Secret Speech of Nikita Khrushchev to the CPSU listing a devastatingly long and detailed list of atrocities committed by and in the name of Joseph Stalin had a cataclysmic effect on the previously Stalinism, Stalinist majority membership Communist Party. Membership plummeted and the leadership briefly faced a challenge from a loose grouping led by ''

The rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as the leader of the CPSU brought unprecedented changes in Soviet Union–United States relations, American–Soviet relations. Initially, American Communists welcomed Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika initiatives to restructure and revitalize Soviet socialism. However, as reforms were carried out, Neoliberalism, neoliberal leaders Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher began to praise Gorbachev, which prompted Communists to double take on their assessment. As the liberalization of the Soviet system began to introduce more aspects of Western world, Western society into the Soviet Union, party leader Gus Hall came out in condemnation of these reforms in 1989, describing them as a counter-revolution to restore capitalism. This effectively liquidated relations between the two Communist parties which would be dissolved less than two years later.

The cutoff of funds resulted in a financial crisis, which forced the Communist Party to cut back publication in 1990 of the party newspaper, the ''People's World, People's Daily World'', to weekly publication, the ''People's Weekly World''. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a crisis in doctrine ensued. The Communist Party's vision of the future development of socialism had to be completely changed due to the extreme change in the balance of global forces. The more moderate reformists, including Angela Davis, left the party altogether, forming a new organization called the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS). In an interview, Charlene Mitchell, one of the members who left the party with Angela Davis, explained how she and others felt the party remained closed and failed to open up discussions among members. Many saw the party as slow and impartial to adjustment, one key area being their approach to a labor force that was becoming less and less industrial in the United States. After the attempt on Gorbachev's life and Gus Hall's ensuing comments in which he sided with the coup, many, even those close to him began to question his judgement.

The remaining Communists struggled with questions of identity in the post-Soviet world, some of which that are still part of Communist Party politics today. The party was left reeling after the split and was plagued by many of the same issues yet maintained Gus Hall as General Secretary.

The rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as the leader of the CPSU brought unprecedented changes in Soviet Union–United States relations, American–Soviet relations. Initially, American Communists welcomed Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika initiatives to restructure and revitalize Soviet socialism. However, as reforms were carried out, Neoliberalism, neoliberal leaders Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher began to praise Gorbachev, which prompted Communists to double take on their assessment. As the liberalization of the Soviet system began to introduce more aspects of Western world, Western society into the Soviet Union, party leader Gus Hall came out in condemnation of these reforms in 1989, describing them as a counter-revolution to restore capitalism. This effectively liquidated relations between the two Communist parties which would be dissolved less than two years later.

The cutoff of funds resulted in a financial crisis, which forced the Communist Party to cut back publication in 1990 of the party newspaper, the ''People's World, People's Daily World'', to weekly publication, the ''People's Weekly World''. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a crisis in doctrine ensued. The Communist Party's vision of the future development of socialism had to be completely changed due to the extreme change in the balance of global forces. The more moderate reformists, including Angela Davis, left the party altogether, forming a new organization called the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS). In an interview, Charlene Mitchell, one of the members who left the party with Angela Davis, explained how she and others felt the party remained closed and failed to open up discussions among members. Many saw the party as slow and impartial to adjustment, one key area being their approach to a labor force that was becoming less and less industrial in the United States. After the attempt on Gorbachev's life and Gus Hall's ensuing comments in which he sided with the coup, many, even those close to him began to question his judgement.

The remaining Communists struggled with questions of identity in the post-Soviet world, some of which that are still part of Communist Party politics today. The party was left reeling after the split and was plagued by many of the same issues yet maintained Gus Hall as General Secretary.

International Communist Opposition

The Right Opposition (, ''Pravaya oppozitsiya'') or Right Tendency (, ''Praviy uklon'') in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a conditional label formulated by Joseph Stalin in fall of 1928 in regards the opposition against certain me ...

(CO), which was initially larger than the Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

s, but it failed to survive past 1941. Lovestone had initially called his faction the Communist Party (Majority Group)

The Lovestoneites, led by former General Secretary of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) Jay Lovestone, were a small American oppositionist communist movement of the 1930s. The organization emerged from a factional fight in the CPUSA in 1929 and un ...

in the expectation that the majority of party members would join him, but only a few hundred people joined his new organization.

1928–1935: Third Period

social fascists

Social fascism (also socio-fascism) was a theory that was supported by the Communist International (Comintern) and affiliated communist parties in the early 1930s that held that social democracy was a variant of fascism because it stood in the way ...

". The impact of this policy in the United States was counted in membership figures. In 1928, there were about 24,000 members. By 1932, the total had fallen to 6,000 members. Despite the changes in the USSR, the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

(Comintern) still played a large role in selecting CPUSA officials, additionally CPUSA and the Comintern still exchanged delegates during the 1930s, and CPUSA still accepted funding from Moscow.

Opposing Stalin's Third Period

The Third Period is an ideological concept adopted by the Communist International (Comintern) at its Sixth World Congress, held in Moscow in the summer of 1928. It set policy until reversed when the Nazis took over Germany in 1933.

The Comint ...

policies in the Communist Party was James P. Cannon. For this action, he was expelled from the party. Cannon then founded the CLA with Max Shachtman and Martin Abern and started publishing ''The Militant

''The Militant'' is an international socialist newsweekly connected to the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Pathfinder Press. It is published in the United States and distributed in other countries such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Aus ...

''. It declared itself to be an external faction of the Communist Party until—as the Trotskyists saw it—Stalin's policies in Germany helped Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

take power. At that point, they started working towards the founding of a new international, the Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) is a revolutionary socialist international organization consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, also known as Trotskyists, whose declared goal is the overthrowing of global capitalism and the establishment of wor ...

(FI).

In the United States, the principal impact of the Third Period was to end the Communist Party's efforts to organize within the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

(AFL) through the TUEL and to turn its efforts into organizing dual unions

Dual unionism is the development of a union or political organization parallel to and within an existing labor union. In some cases, the term may refer to the situation where two unions claim the right to organize the same workers.

Dual unionism i ...

through the Trade Union Unity League

The Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) was an industrial union umbrella organization under the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) between 1929 and 1935. The group was an American affiliate of the Red International of Labor Unions. The fo ...

. Foster went along with this change, even though it contradicted the policies he had fought for previously. In 1928 Communist Party USA nominated William Z. Foster for the presidential election, he accepted with the aim of further growing class consciousness, they garnered over 48,000 votes (despite only having 9,000 members). Many of the party leaders, including Foster himself, knew that they were never going to win office. However they did stir some class consciousness but also butted heads with some unions during their campaigning, including the AFL. The party was ballot qualified in New York from 1932 to 1936.

By 1930, the party adopted the slogan of "the united front from below". The Communist Party devoted much of its energy in the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

to organizing the unemployed

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the referen ...

, attempting to found "red" unions, championing the rights of African Americans and fighting evictions

Eviction is the removal of a tenant from rental property by the landlord. In some jurisdictions it may also involve the removal of persons from premises that were foreclosed by a mortgagee (often, the prior owners who defaulted on a mortgage ...

of farmers and the working poor. At the same time, the party attempted to weave its sectarian revolutionary politics into its day-to-day defense of workers, usually with only limited success. They recruited more disaffected members of the Socialist Party and an organization of African American socialists called the African Blood Brotherhood

The African Blood Brotherhood for African Liberation and Redemption (ABB) was a U.S. black liberation organization established in 1919 in New York City by journalist Cyril Briggs. The group was established as a propaganda organization built on th ...

(ABB), some of whose members, particularly Harry Haywood

Harry Haywood (February 4, 1898 – January 4, 1985) was an American political activist who was a leading figure in both the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). His goal was to connec ...

, would later play important roles in Communist work among blacks.

In 1928 Communist Party USA changed its constitution and called for the right of self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

of African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

in the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Communist Party USA would go on to help build the Alabama Sharecroppers Union and class consciousness in the "Black Belt' of the American South in the 1930s. Self-determination was never a realistic goal in the context of the American South, and one prominent black communist even admitted as such in 1935. In 1931 the party began to organize the Alabama Sharecroppers Union in Tallapoosa County, Alabama

Tallapoosa County is located in the east-central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama."ACES Tallapoosa County Office" (links/history), Alabama Cooperative Extension System (ACES), 2007, webpageACES-Tallapoosa As of the 2020 census, the populati ...

. However early efforts in Camp Hill, Alabama

Camp Hill is a town in Tallapoosa County, Alabama, United States. It was incorporated in 1895. At the 2010 census the population was 1,014, down from 1,273 in 2000. Camp Hill is the home to Southern Preparatory Academy (formerly known as "Lyman Wa ...

where plagued with poor organization and brushes with local authorities resulting in arrests and tension. The party saw the creation of the sharecroppers union as key in the fight for self-determination and eventually reorganized in an effort to keep the movement alive. The area was divided into smaller locals and built outwards into four different counties. The union was organized around seven basic demands that were largely economic and centered around the economic rights of sharecroppers. In 1935 when the Alabama Sharecroppers Union had 12,000 members they called a strike in 7 counties across Alabama, demanding an increase in wages from roughly 35 cents to a dollar. The strike succeed outright on 35 plantations and wages were raised to 75 cents on other plantations. CPUSA's campaign in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

helped lay the groundwork for the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. When CPUSA called for the right of self-determination and recognized distinctions in the African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

struggle they created a new political ally in the working class and had the means to become an interracial party that could stand clearly against segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

and racial injustice. CPUSA's actions in the South represented a changing in their actions and goals that would become solidified in their 1938 constitution as they moved towards more local goals.

In 1932, the retiring head of the party, William Z. Foster, published a book entitled '' Toward Soviet America'', which laid out the Communist Party's plans for revolution and the building of a new socialist society based on the model of Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. In that same year, Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Duri ...

became General Secretary of the Communist Party. At first, Browder moved the party closer to Soviet interests and helped to develop its secret apparatus or underground network. He also assisted in the recruitment of espionage sources and agents for the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. Browder's own younger sister Margerite was an NKVD operative in Europe until removed from those duties at Browder's request. It was at this point that the party's foreign policy platform came under the complete control of Stalin, who enforced his directives through his secret police and foreign intelligence service, the NKVD. The NKVD controlled the secret apparatus of the Communist Party.

During the Great Depression in the United States

In the United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high un ...

, many Americans became disillusioned with capitalism and some found communist ideology

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

appealing. Others were attracted by the visible activism of American Communists on behalf of a wide range of social and economic causes, including the rights of African Americans, workers and the unemployed. Still others, alarmed by the rise of the Franquists in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, admired the Soviet Union's early and staunch opposition to fascism. The membership of the Communist Party swelled from 6,822 at the beginning of the decade to 66,000 by the end. It held mass rallies that filled Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

.Katznelson, Ira (2013). ''Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of our Time''. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. . .

1935–1939: Popular Front

The ideological rigidity of the third period began to crack with two events: the election of

The ideological rigidity of the third period began to crack with two events: the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

as President of the United States in 1932 and Adolf Hitler's rise to power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

in Germany in 1933. Roosevelt's election and the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a US labor law and consumer law passed by the 73rd US Congress to authorize the president to regulate industry for fair wages and prices that would stimulate economic recovery. It also e ...

in 1933 sparked a tremendous upsurge in union organizing

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers.

In some unions, the orga ...

in 1933 and 1934. While the party line still favored creation of autonomous revolutionary unions, party activists chose to fold up those organizations and follow the mass of workers into the AFL unions they had been attacking.

The Seventh Congress of the Comintern made the change in line official in 1935, when it declared the need for a popular front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

of all groups opposed to fascism. The Communist Party abandoned its opposition to the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

, provided many of the organizers for the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

(CIO) and began supporting African American civil rights. The party also sought unity with forces to its right. Earl Browder offered to run as Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas (November 20, 1884 – December 19, 1968) was an American Presbyterian minister who achieved fame as a socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.

Early years

Thomas was the ...

' running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint Ticket (election), ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate ...

on a joint Socialist Party-Communist Party ticket in the 1936 presidential election, but Thomas rejected this overture. The gesture did not mean that much in practical terms since by 1936 the Communist Party effectively supporting Roosevelt in much of his trade union work. While continuing to run its own candidates for office, the party pursued a policy of representing the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

as the lesser evil in elections.

Party members also rallied to the defense of the Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

during this period after a Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

military uprising moved to overthrow it, resulting in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

(1936–1939). The Communist Party along with leftists throughout the world raised funds for medical relief while many of its members made their way to Spain with the aid of the party to join the Lincoln Brigade, one of the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

. Among its other achievements, the Lincoln Brigade was the first American military force to include blacks and whites integrated on an equal basis. Intellectually, the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

period saw the development of a strong Communist influence in intellectual and artistic life. This was often through various organizations influenced or controlled by the party, or as they were pejoratively known, " fronts".

The party under Browder supported Stalin's show trials

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so th ...

in the Soviet Union, called the Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against "Trotskyists" and members of "Right Opposition" of the Communist Party of th ...

. Therein, between August 1936 and mid-1938 the Soviet government indicted, tried and shot virtually all of the remaining Old Bolsheviks

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

. Beyond the show trials lay a broader purge, the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

, that killed millions. Browder uncritically supported Stalin, likening Trotskyism to " cholera germs" and calling the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

"a signal service to the cause of progressive humanity". He compared the show trial defendants to domestic traitors Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

, Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

, disloyal War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

and Confederate secessionists while likening persons who "smeared" Stalin's name to those who had slandered Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

1939–1947: World War II and aftermath

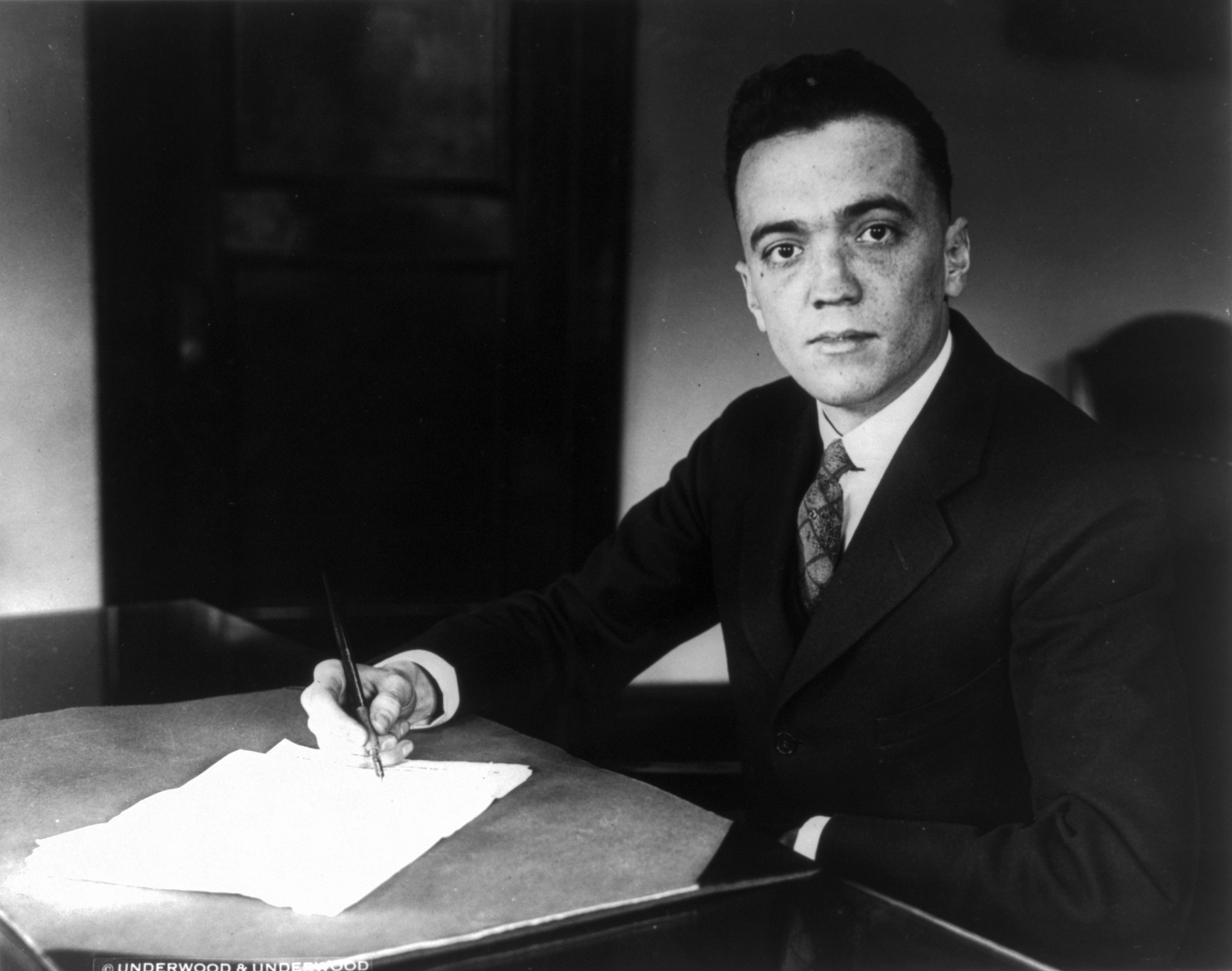

The Communist Party was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. Although membership in the party rose to about 66,000 by 1939, nearly 20,000 members left the party by 1943, after the Soviet Union signed the

The Communist Party was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. Although membership in the party rose to about 66,000 by 1939, nearly 20,000 members left the party by 1943, after the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

on August 23, 1939. While general secretary Browder at first attacked Germany for its September 1, 1939 invasion of western Poland, on September 11 the Communist Party received a blunt directive from Moscow denouncing the Polish government. Between September 14–16, party leaders bickered about the direction to take.

On September 17, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.

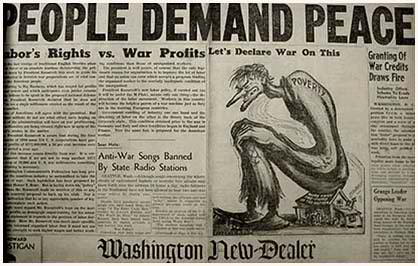

The British, French and German Communist parties, all originally war supporters, abandoned their anti-fascist crusades, demanded peace and denounced Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

governments. The Communist Party turned the focus of its public activities from anti-fascism to advocating peace, not only opposing military preparations, but also condemning those opposed to Hitler. The party attacked British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

and French leader Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, and the Prime Minister of France who signed the Munich Agreement before the outbreak of World War II.

Daladier was born in Carpentr ...

, but it did not at first attack President Roosevelt, reasoning that this could devastate American Communism, blaming instead Roosevelt's advisors.

In October and November, after the Soviets invaded Finland and forced mutual assistance pacts from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the Communist Party considered Russian security sufficient justification to support the actions. Secret short wave radio broadcasts in October from Comintern leader Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

ordered Browder to change the party's support for Roosevelt. On October 23, the party began attacking Roosevelt. The party was active in the isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

.

The Communist Party dropped its boycott of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

goods, spread the slogans " The Yanks Are Not Coming" and "Hands Off", set up a "perpetual peace vigil" across the street from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

and announced that Roosevelt was the head of the "war party of the American bourgeoisie". By April 1940, the party ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

s line seemed not so much antiwar as simply pro-German. A pamphlet stated the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

had just as much to fear from Britain and France as they did Germany. In August 1940, after NKVD agent Ramón Mercader

Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río (7 February 1913 – 18 October 1978),Photograph oMercader's Gravestone/ref> more commonly known as Ramón Mercader, was a Spanish communist and NKVD agent, who assassinated Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Tr ...

killed Trotsky with an ice axe

An ice axe is a multi-purpose hiking and climbing tool used by mountaineers in both the ascent and descent of routes that involve snow, ice, or frozen conditions. Its use depends on the terrain: in its simplest role it is used like a walking ...

, Browder perpetuated Moscow's fiction that the killer, who had been dating one of Trotsky's secretaries, was a disillusioned follower. In allegiance to the Soviet Union, the party changed this policy again after Hitler broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact by attacking the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

Throughout the rest of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Communist Party continued a policy of militant, if sometimes bureaucratic, trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

ism while opposing strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Labor (economics), work. A strike usually takes place in response to grievance (labour), employee grievance ...

s at all costs. The leadership of the Communist Party was among the most vocal pro-war voices in the United States, advocating unity against fascism, supporting the prosecution of leaders of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) under the newly enacted Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

and opposing A. Philip Randolph's efforts to organize a march on Washington to dramatize black workers' demands for equal treatment on the job. Prominent party members and supporters, such as Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo (December 9, 1905 – September 10, 1976) was an American screenwriter who scripted many award-winning films, including ''Roman Holiday'' (1953), ''Exodus'', ''Spartacus'' (both 1960), and ''Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (1944) ...

and Pete Seeger

Peter Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014) was an American folk singer and social activist. A fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, Seeger also had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of the Weavers, notably ...

, recalled anti-war material they had previously released. In turn, the U.S. government began to lift prewar restrictions on the CPUSA in order to maintain good United States-Soviet Union relations during the war.

Earl Browder expected the wartime coalition between the Soviet Union and the West to bring about a prolonged period of social harmony after the war. In order better to integrate the Communist movement into American life, the party was officially dissolved in 1944 and replaced by a Communist Political Association. This coincided with the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

's (CPI) Salerno turn accommodation with other anti-fascist parties in 1944. However, that harmony proved elusive and the international Communist movement swung to the left after the war ended. Browder found himself isolated when the Duclos letter

Jacques Duclos (2 October 189625 April 1975) was a French Communist politician who played a key role in French politics from 1926, when he entered the French National Assembly after defeating Paul Reynaud, until 1969, when he won a substantial p ...

from the leader of the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Unit ...

(FCP), attacking Browderism (an accommodation with American political conditions), received wide circulation amongst Communist officials internationally. As a result of this, he was retired and replaced in 1945 by William Z. Foster, who would remain the senior leader of the party until his own retirement in 1958.

In line with other Communist parties worldwide, the Communist Party also swung to the left and as a result experienced a brief period in which a number of internal critics argued for a more leftist stance than the leadership was willing to countenance. The result was the expulsion of a handful of "premature anti-revisionists

Anti-revisionism is a position within Marxism–Leninism which emerged in the 1950s in opposition to the reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Where Khrushchev pursued an interpretation that differed from his predecessor Joseph Stalin, ...

". The National Republican (newspaper)

The ''National Republican'' (1860–1888) was an American, English-language daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C.

History

The paper was founded in November 1860 upon the election of Abraham Lincoln as the first United States President fr ...

had at a time estimated that there were over a million communists in America.

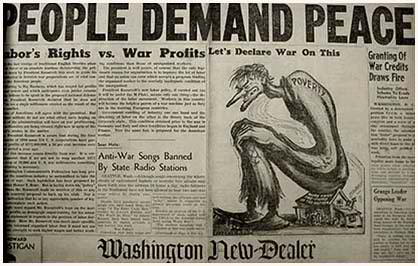

1947–1958: Second Red Scare

More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the Communist Party with the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. The

More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the Communist Party with the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. The Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran ...

's loyalty oath program, introduced in 1947, drove some leftists out of federal employment and more importantly legitimized the notion of Communists as subversives to be exposed and expelled from public and private employment. The House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

(HUAC), created in 1938 amid concerns over the spread of communism and political subversion within the United States, had a focus on investigating and in some cases trying citizens in court, who had communist ties, including citizens tied to CPUSA. These actions inspired local governments to adopt loyalty oaths and investigative commissions of their own. Private parties, such as the motion picture industry and self-appointed watchdog groups, extended the policy still further. This included the still controversial blacklist of actors, writers and directors in Hollywood who had been Communists or who had fallen in with Communist-controlled or influenced organizations in the pre-war and wartime years. The union movement purged party members as well. The CIO formally expelled a number of left-led unions in 1949 after internal disputes triggered by the party's support for Henry Wallace's 1948

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

candidacy for president and its opposition to the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

while other labor leaders sympathetic to the Communist Party either were driven out of their unions or dropped their alliances with the party.

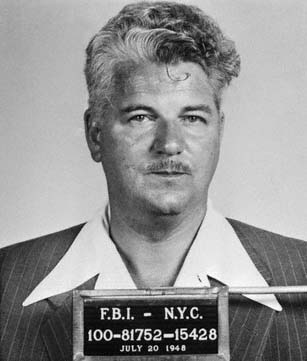

In 1949's Foley Square trial

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of US federal government prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. Leaders of the ...

, the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI) prosecuted eleven members of the Communist Party's leadership, including Gus Hall

Gus Hall (born Arvo Kustaa Halberg; October 8, 1910 – October 13, 2000) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and a perennial candidate for president of the United States. He was the Communist Party nominee in the ...

and Eugene Dennis

Francis Xavier Waldron (August 10, 1905 – January 31, 1961), best known by the pseudonym Eugene Dennis and Tim Ryan, was an American communist politician and union organizer, best remembered as the long-time leader of the Communist Party USA a ...

. The prosecution argued that the party endorsed a violent overthrow of the government, which was illegal due the 1940 passage of the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

; but the defendants countered that they advocated for a peaceful transition to socialism and that the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

's guarantee of free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been ...

and association protected their membership in a political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

. The trial—held in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

's Foley Square courthouse

The Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse (originally the United States Courthouse or the Foley Square Courthouse) is a 37-story courthouse at 40 Centre Street on Foley Square in the Civic Center neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York ...

—was widely publicized by the media and was featured on the cover of ''Time'' magazine twice. Large numbers of protesters supporting the Communist defendants protested outside the courthouse daily. The defense attorneys used a "labor defense" strategy which attacked the trial as a capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

venture that would not provide a fair outcome to proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...