History of the British Raj on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

After the first war for Indian independence, the British Government took over the administration to establish the

File:George Robinson 1st Marquess of Ripon.jpg,

In terms of the longer lasting effects and legacies of the economic impact of the British Raj, the impact predominantly stems from the irregular investment of areas of infrastructure. Simon Carey explains how the investment into Indian society was 'narrowly focused' and favoured the growth of transportation of goods and workers. Therefore India has since seen an uneven economic development of society. For example, Acemoglu et al. (2001) identify how the inability of certain areas of rural India to cope with disease and famine best explain this uneven development of the nation. Carey also points out that a lasting impact of the British Raj is the transformation of India into an agricultural trading economy. Therefore, some areas of India, predominantly in affluent urban areas, have benefited from the legacies of the British Raj in the long term due to the transformation of Indian economic culture to a production based economy. However, the majority of Indian society has experienced a negative impact of the British Raj, especially in rural and suburban areas, due to the focus of investment into transport such as railways and canals rather than into healthcare and primary education.

File:John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn - Project Gutenberg eText 17976.jpg,

Consequently, in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu announced the new constitutional reforms, a sedition committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating wartime revolutionary conspiracies and the

Consequently, in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu announced the new constitutional reforms, a sedition committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating wartime revolutionary conspiracies and the

The

The

full text

*. *. * *. * *. *. *. * Rees, Rosemary. ''India 1900–47'' (Heineman, 2006), textbook. * Riddick, John F. ''Who Was Who in British India'' (1998); 5000 entrie

excerpt

*. *. *. *. *.

British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

. The British Raj was the period of British rule on the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

between 1858 and 1947. The system of governance was instituted in 1858 when the rule of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

was transferred to the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

in the person of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

.

It lasted until 1947, when the British provinces of India were partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the ''Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

'' and the ''Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

'', leaving the princely states to choose between them. Most of the princely states decided to join either Dominion of India or Dominion of Pakistan, except the state of Jammu and Kashmir. It was only at the last moment that Jammu and Kashmir agreed to sign the " Instrument of Accession" with India. The two new dominions later became the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

(the eastern half of which, still later, became the People's Republic of Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

). The province of Burma in the eastern region of the Indian Empire had been made a separate colony in 1937 and became independent in 1948.

The East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

was an English and later British joint-stock company. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with Mughal India and the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

, and later with Qing China. The company ended up seizing control of large parts of the Indian subcontinent, colonised parts of Southeast Asia, and colonised Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

after a war with Qing China.

Prelude

Effects on the economy

In the later half of the 19th century, both the direct administration of India by the British Crown and the technological change ushered in by theindustrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, had the effect of closely intertwining the economies of India and Great Britain. In fact, many of the major changes in transport and communications (that are typically associated with Crown Rule of India) had already begun before the Mutiny. Since Dalhousie had embraced the technological change then rampant in Great Britain, India too saw rapid development of all those technologies. Railways, roads, canals, and bridges were rapidly built in India and telegraph links equally rapidly established in order that raw materials, such as cotton, from India's hinterland could be transported more efficiently to ports, such as Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, for subsequent export to England. Likewise, finished goods from England were transported back just as efficiently, for sale in the rising (burgeoning) Indian markets. However, unlike Britain itself, where the market risks for the infrastructure development were borne by private investors, in India, it was the taxpayers—primarily farmers and farm-labourers—who endured the risks, which, in the end, amounted to £50 million. In spite of these costs, very little skilled employment was created for Indians. By 1920, with a history of 60 years of its construction, only ten per cent of the "superior posts" in the railways were held by Indians.

The rush of technology was also changing the agricultural economy in India: by the last decade of the 19th century, a large fraction of some raw materials—not only cotton, but also some food-grains—were being exported to faraway markets. Consequently, many small farmers, dependent on the whims of those markets, lost land, animals, and equipment to money-lenders. More tellingly, the latter half of the 19th century also saw an increase in the number of large-scale famines in India

Famine had been a recurrent feature of life in the South Asian subcontinent countries of India and Bangladesh, most accurately recorded during British rule. Famines in India resulted in more than 30 million deaths over the course of the 18th, ...

. Although famines were not new to the subcontinent, these were particularly severe, with tens of millions dying, and with many critics, both British and Indian, laying the blame at the doorsteps of the lumbering colonial administrations.

Lord Ripon

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, (24 October 1827 – 9 July 1909), styled Viscount Goderich from 1833 to 1859 and known as the Earl of Ripon in 1859 and as the Earl de Grey and Ripon from 1859 to 1871, was a British p ...

, the Liberal Viceroy of India, who instituted the Famine Code

File:Agra canal headworks1871a.jpg, The Agra canal

The Agra Canal is an important Indian irrigation work which starts from Okhla in Delhi. The Agra canal originates at the Okhla barrage, downstream of Nizamuddin bridge.

The canal receives its water from the Yamuna River at Okhla, about to t ...

(c. 1873), a year away from completion. The canal was closed to navigation in 1904 to increase irrigation and aid in famine-prevention.

File:India railways1909a.jpg, Railway map of India in 1909. Railway construction in India had begun in 1853.

File:Victoriaterminus1903.JPG, A 1903 stereographic image of Victoria Terminus

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (officially Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, Bombay station code: CSMT ( mainline)/ST (suburban)), is a historic railway terminus and UNESCO World Heritage Site in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

The terminus was d ...

, Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, by Underwood and Underwood. The station was completed in 1888.

Beginnings of self-government

The first steps were taken toward self-government in British India in the late 19th century with the appointment of Indian counsellors to advise the British viceroy and the establishment of provincial councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in legislative councils with theIndian Councils Act 1892

The Indian Councils Act 1892 was an Act of British Parliament that introduced various amendments to the composition and function of legislative councils in British India. Most notably, the act expanded the number of members in the central and ...

. Municipal Corporation

A municipal corporation is the legal term for a local governing body, including (but not necessarily limited to) cities, counties, towns, townships, charter townships, villages, and boroughs. The term can also be used to describe municipally ...

s and District Boards were created for local administration; they included elected Indian members

The Indian Councils Act 1909

The Indian Councils Act 1909, commonly known as the Morley–Minto or Minto–Morley Reforms, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that brought about a limited increase in the involvement of Indians in the governance of British In ...

– also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

was the secretary of state for India, and Gilbert Elliot, fourth earl of Minto, was viceroy) – gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures, known as legislative councils. Indians had previously been appointed to legislative councils, but after the reforms some were elected to them. At the centre, the majority of council members continued to be government-appointed officials, and the viceroy was in no way responsible to the legislature. At the provincial level, the elected members, together with unofficial appointees, outnumbered the appointed officials, but responsibility of the governor to the legislature was not contemplated. Morley made it clear in introducing the legislation to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

that parliamentary self-government was not the goal of the British government.

The Morley-Minto Reforms were a milestone. Step by step, the elective principle was introduced for membership in Indian legislative councils. The "electorate" was limited, however, to a small group of upper-class Indians. These elected members increasingly became an "opposition" to the "official government". The Communal electorates were later extended to other communities and made a political factor of the Indian tendency toward group identification through religion.

John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

, the Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of th ...

from 1905 to 1910, and Gladstonian Liberal. The Indian Councils Act 1909

The Indian Councils Act 1909, commonly known as the Morley–Minto or Minto–Morley Reforms, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that brought about a limited increase in the involvement of Indians in the governance of British In ...

, also known as the ''Minto-Morley Reforms'' allowed Indians to be elected to the Legislative Council.

File:Delhidurbar pc1911.jpg, Picture post card of the Gordon Highlanders marching past King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

and Queen Mary at the Delhi Durbar on December 12, 1911, when the King was crowned Emperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 22 ...

.

File:Indiantroops medical ww1.jpg, Indian medical orderlies attending to wounded soldiers with the ''Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force'' in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

World War I and its causes

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army would take part in the war and their participation would have a wider cultural fallout: news of Indian soldiers fighting and dying with British soldiers, as well as soldiers from dominions like Canada,Australia and New Zealand, would travel to distant corners of the world both in newsprint and by the new medium of the radio. India's international profile would thereby rise and would continue to rise during the 1920s. It was to lead, among other things, to India, under its own name, becoming a founding member of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in 1920 and participating, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (The British Indies), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp. Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

, it would lead to calls for greater self-government for Indians.

In 1916, in the face of new strength demonstrated by the nationalists with the signing of the Lucknow Pact and the founding of the Home Rule leagues, and the realisation, after the disaster in the Mesopotamian campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, troops from Britain, Australia and the vast majority from British India, against the Central Po ...

, that the war would likely last longer, the new Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, cautioned that the Government of India needed to be more responsive to Indian opinion. Towards the end of the year, after discussions with the government in London, he suggested that the British demonstrate their good faith – in light of the Indian war role – through a number of public actions, including awards of titles and honours to princes, granting of commissions in the army to Indians, and removal of the much-reviled cotton excise duty, but most importantly, an announcement of Britain's future plans for India and an indication of some concrete steps. After more discussion, in August 1917, the new Liberal Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of th ...

, Edwin Montagu

Edwin Samuel Montagu PC (6 February 1879 – 15 November 1924) was a British Liberal politician who served as Secretary of State for India between 1917 and 1922. Montagu was a "radical" Liberal and the third practising Jew (after Sir Herbe ...

, announced the British aim of "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration, and the gradual development of self-governing institutions, with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." This envisioned reposing confidence in the educated Indians, so far disdained as an unrepresentative minority, who were described by Montague as "Intellectually our children". The pace of the reforms where to be determined by Britain as and when the Indians were seen to have earned it. However, although the plan envisioned limited self-government at first only in the provinces – with India emphatically within the British Empire – it represented the first British proposal for any form of representative government in a non-white colony.

Earlier, at the onset of World War I, the reassignment of most of the British army in India to Europe and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

had led the previous Viceroy, Lord Harding, to worry about the "risks involved in denuding India of troops." Revolutionary violence had already been a concern in British India; consequently in 1915, to strengthen its powers during what it saw was a time of increased vulnerability, the Government of India passed the Defence of India Act, which allowed it to intern politically dangerous dissidents without due process and added to the power it already had – under the 1910 Press Act – both to imprison journalists without trial and to censor the press. Now, as constitutional reform began to be discussed in earnest, the British began to consider how new moderate Indians could be brought into the fold of constitutional politics and simultaneously, how the hand of established constitutionalists could be strengthened. However, since the reform plan was devised during a time when extremist violence had ebbed as a result of increased wartime governmental control and it now feared a revival of revolutionary violence, the government also began to consider how some of its wartime powers could be extended into peacetime.

Consequently, in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu announced the new constitutional reforms, a sedition committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating wartime revolutionary conspiracies and the

Consequently, in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu announced the new constitutional reforms, a sedition committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating wartime revolutionary conspiracies and the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

links to the violence in India, with the unstated goal of extending the government's wartime powers. The Rowlatt committee presented its report in July 1918 and identified three regions of conspiratorial insurgency: Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, the Bombay presidency, and the Punjab. To combat subversive acts in these regions, the committee recommended that the government use emergency powers akin to its wartime authority, which included the ability to try cases of sedition by a panel of three judges and without juries, exaction of securities from suspects, governmental overseeing of residences of suspects, and the power for provincial governments to arrest and detain suspects in short-term detention facilities and without trial.

With the end of World War I, there was also a change in the economic climate. By year's end 1919, 1.5 million Indians had served in the armed services in either combatant or non-combatant roles, and India had provided £146 million in revenue for the war. The increased taxes coupled with disruptions in both domestic and international trade had the effect of approximately doubling the index of overall prices in India between 1914 and 1920. Returning war veterans, especially in the Punjab, created a growing unemployment crisis and post-war inflation led to food riots in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal provinces, a situation that was made only worse by the failure of the 1918–19 monsoon and by profiteering and speculation. The global influenza epidemic and the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

of 1917 added to the general jitters; the former among the population already experiencing economic woes, and the latter among government officials, fearing a similar revolution in India.

To combat what it saw as a coming crisis, the government now drafted the Rowlatt committee's recommendations into two Rowlatt Bills

The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, was a law that applied in British India. It was a legislative council act passed by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi on 18 March 1919, indefinitel ...

. Although the bills were authorised for legislative consideration by Edwin Montagu, they were done so unwillingly, with the accompanying declaration, "I loathe the suggestion at first sight of preserving the Defence of India Act in peace time to such an extent as Rowlatt and his friends think necessary." In the ensuing discussion and vote in the Imperial Legislative Council

The Imperial Legislative Council (ILC) was the legislature of the British Raj from 1861 to 1947. It was established under the Charter Act of 1853 by providing for the addition of 6 additional members to the Governor General Council for legislativ ...

, all Indian members voiced opposition to the bills. The Government of India was nevertheless able to use of its "official majority" to ensure passage of the bills early in 1919. However, what it passed, in deference to the Indian opposition, was a lesser version of the first bill, which now allowed extrajudicial powers, but for a period of exactly three years and for the prosecution solely of "anarchical and revolutionary movements," dropping entirely the second bill involving modification of the Indian Penal Code

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) is the official criminal code of India. It is a comprehensive code intended to cover all substantive aspects of criminal law. The code was drafted on the recommendations of first law commission of India established ...

. Even so, when it was passed the new Rowlatt Act

The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, was a law that applied in British India. It was a legislative council act passed by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi on 18 March 1919, indefinitel ...

aroused widespread indignation throughout India and brought Mohandas Gandhi to the forefront of the nationalist movement.

Montagu–Chelmsford Report 1919

Meanwhile, Montagu and Chelmsford themselves finally presented their report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter. After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee for the purpose of identifying who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, theGovernment of India Act 1919

The Government of India Act 1919 (9 & 10 Geo. 5 c. 101) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was passed to expand participation of Indians in the government of India. The Act embodied the reforms recommended in the report o ...

(also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more briefly known as the Mont–Ford Reforms, were introduced by the colonial government to introduce self-governing institutions gradually in British India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Montagu, th ...

) was passed in December 1919. The new Act enlarged the provincial councils and converted the Imperial Legislative Council

The Imperial Legislative Council (ILC) was the legislature of the British Raj from 1861 to 1947. It was established under the Charter Act of 1853 by providing for the addition of 6 additional members to the Governor General Council for legislativ ...

into an enlarged Central Legislative Assembly

The Central Legislative Assembly was the lower house of the Imperial Legislative Council, the legislature of British India. It was created by the Government of India Act 1919, implementing the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms. It was also sometim ...

. It also repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavourable votes. Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications and income-tax were retained by the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue and local self-government were transferred to the provinces. The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council. The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate. In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts. Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principal of "communal representation", an integral part of the Minto–Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, Sikhs, Indian Christians

Christianity is India's third-largest religion with about 27.8 million adherents, making up 2.3 percent of the population as of the 2011 census. The written records of the Saint Thomas Christians state that Christianity was introduced to th ...

, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils. The Montagu–Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.

Round Table Conferences 1930–31–32

The threeRound Table Conferences

The three Round Table Conferences of 1930–1932 were a series of peace conferences organized by the British Government and Indian political personalities to discuss constitutional reforms in India. These started in November 1930 and ended in Dec ...

of 1930–32 were a series of conferences organised by the British Government to discuss constitutional reforms in India. They were conducted according to the recommendation of Muslim leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah to the Viceroy Lord Irwin

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

and the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and by the report submitted by the Simon Commission in May 1930. Demands for swaraj, or self-rule, in India had been growing increasingly strong. By the 1930s, many British politicians believed that India needed to move towards dominion status

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

. However, there were significant disagreements between the Indian and the British leaders that the Conferences could not resolve.

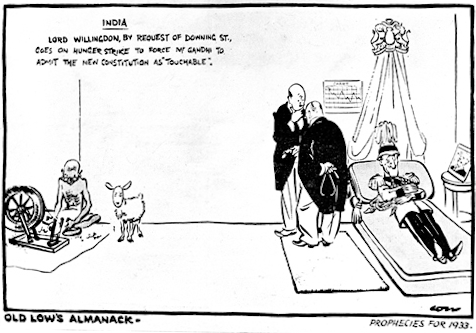

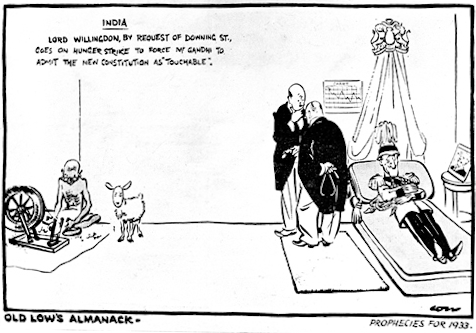

Willingdon imprisons leaders of Congress

In 1932 the Viceroy,Lord Willingdon

Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Willingdon (12 September 1866 – 12 August 1941), was a British Liberal politician and administrator who served as Governor General of Canada, the 13th since Canadian Confederation, and as Viceroy and ...

, after the failure of the three Round Table Conferences (India)

The three Round Table Conferences of 1930–1932 were a series of peace conferences organized by the British Government and Indian political personalities to discuss constitutional reforms in India. These started in November 1930 and ended in De ...

in London, now confronted Gandhi's Congress in action. The India Office told Willingdon that he should conciliate only those elements of Indian opinion that were willing to work with the Raj. That did not include Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, which launched its Civil Disobedience Movement on 4 January 1932. Therefore, Willingdon took decisive action. He imprisoned Gandhi. He outlawed the Congress; he rounded up all members of the Working Committee and the Provincial Committees and imprisoned them; and he banned Congress youth organisations. In total he imprisoned 80,000 Indian activists. Without most of their leaders, protests were uneven and disorganised, boycotts were ineffective, illegal youth organisations proliferated but were ineffective, more women became involved, and there was terrorism, especially in the North-West Frontier Province. Gandhi remained in prison until 1933. Willingdon relied on his military secretary, Hastings Ismay

Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (21 June 1887 – 17 December 1965), was a diplomat and general in the British Indian Army who was the first Secretary General of NATO. He also was Winston Churchill's chief military assistant during the ...

, for his personal safety.

Communal Award: 1932

MacDonald, trying to resolve the critical issue of how Indians would be represented, on 4 August 1932 granting separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, and Europeans in India and increased the number of provinces that offered separate electorates to Anglo-Indians and Indian Christians. Untouchables (now known as theDalits

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold varna system of Hinduism and were seen as forming ...

) obtained a separate electorate. That outraged Gandhi because he firmly believed they had to be treated as Hindus. He and Congress rejected the proposal, but it went into effect anyway.

Government of India Act (1935)

In 1935, after the failure of the Round Table Conferences, the British Parliament approved the Government of India Act 1935, which authorized the establishment of independent legislative assemblies in all provinces of British India, the creation of a central government incorporating both the British provinces and the princely states, and the protection of Muslim minorities. The future Constitution of independent India would owe a great deal to the text of this act. The act also provided for a bicameral national parliament and an executive branch under the purview of the British government. Although the national federation was never realized, nationwide elections for provincial assemblies were held in 1937. Despite initial hesitation, the Congress took part in the elections and won victories in seven of the eleven provinces of British India, and Congress governments, with wide powers, were formed in these provinces. In Great Britain, these victories were to later turn the tide for the idea of Indian independence.World War II

India played a major role in the Allied war effort against both Japan and Germany. It provided over 2 million soldiers, who fought numerous campaigns in the Middle East, and in the India-Burma front and also supplied billions of pounds to the British war effort. The Muslim and Sikh populations were strongly supportive of the British war effort, but the Hindu population was divided. Congress opposed the war, and tens of thousands of its leaders were imprisoned in 1942–45. A major famine in eastern India led to hundreds of thousands of deaths by starvation, and remains a highly controversial issue regarding Churchill's reluctance to provide emergency food relief. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the viceroy,Lord Linlithgow

Marquess of Linlithgow, in the County of Linlithgow or West Lothian, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 23 October 1902 for John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun. The current holder of the title is Adrian Hope.

This ...

, declared war on India's behalf without consulting Indian leaders, leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest. The Muslim League, in contrast, supported Britain in the war effort; however, it now took the view that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress. Hindus not affiliated with the Congress typically supported the war. The two major Sikh factions, the Unionists and the Akali Dal, supported Britain and successfully urged large numbers of Sikhs to volunteer for the army.

Quit India movement or the Bharat Chhodo Andolan

The British sent a high levelCripps Mission

The Cripps Mission was a failed attempt in late March 1942 by the British government to secure full Indian cooperation and support for their efforts in World War II. The mission was headed by a senior minister Stafford Cripps. Cripps belonged to th ...

in 1942 to secure Indian nationalists' co-operation in the war effort in exchange for postwar independence and dominion status. Congress demanded immediate independence and the mission failed. Gandhi then launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942, demanding the immediate withdrawal of the British from India or face nationwide civil disobedience. Along with thousands of other Congress leaders, Gandhi was immediately imprisoned, and the country erupted in violent local episodes led by students and later by peasant political groups, especially in Eastern United Provinces, Bihar, and western Bengal. According to John F. Riddick, from 9 August 1942 to 21 September 1942, the Quit India movement:

:attacked 550 post offices, 250 railway stations, damaged many rail lines, destroyed 70 police stations, and burned or damaged 85 other government buildings. There were about 2,500 instances of telegraph wires being cut....The Government of India deployed 57 battalions of British troops to restore order.

The police and Army crushed the resistance in a little more than six weeks; nationalist leaders were imprisoned for the duration.

Bose and the Indian National Army (INA)

Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been ousted from the Congress Party in 1939 following differences with the more conservative high command, turned to Germany and Japan for help with liberating India by force. With Japanese support, he organised the Indian National Army, composed largely of Indian soldiers of the British Indian army who had been captured at Singapore by the Japanese, including many Sikhs as well as Hindus and Muslims. Japan'ssecret service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For ...

had promoted unrest in Southeast Asia to destabilise the British war effort, and came to support a number of puppet and provisional governments in regions under their occupation, such as those of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

; similarly supported was the Provisional Government of Azad Hind

The Provisional Government of Free India (''Ārzī Hukūmat-e-Āzād Hind'') or, more simply, ''Azad Hind'', was an Indian provisional government established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II. It was created in October 194 ...

(Free India), presided over by Bose. Bose's effort, however, was short lived; after the reverses of 1944, the reinforced British Indian Army in 1945 first halted and then reversed the Japanese U Go offensive, beginning the successful part of the Burma Campaign. Bose's Indian National Army surrendered with the recapture of Singapore; Bose died in a plane crash soon thereafter. The British demanded trials

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribun ...

for INA officers, but public opinion—including Congress and even the Indian Army—saw the INA as fighting for Indian independence and demanded a termination. Yasmin Khan says "The INA became the real heroes of the war in India." After a wave of unrest and nationalist violence the trials were stopped.

Finances

Britain borrowed everywhere it could and made heavy purchases of equipment and supplies in India during the war. Previously India owed Britain large sums; now it was reversed. Britain's sterling balances around the world amounted to £3.4 billion in 1945; India's share was £1.3 billion (equivalent to $US 74 billion in 2016 dollars.) In this way the Raj treasury accumulated very large sterling reserves of British pounds that was owed to it by the British treasury. However, Britain treated this as a long-term loan with no interest and no specified repayment date. Just when the money would be made available by London was an issue, for the British treasury was nearly empty by 1945. India's balances totalled to Rs. 17.24 billion in March 1946; of that sum Rs. 15.12 billion �1.134 billionwas split between India and Pakistan when they became independent in August 1947. They finally got the money and India spent all its share by 1957; mostly buying back British owned assets in India.Transfer of Power

The

The All India Azad Muslim Conference The All India Azad Muslim Conference ( ur, ), commonly called the Azad Muslim Conference (literally, "Independent Muslim Conference"), was an organisation of nationalist Muslims in India. Its purpose was advocacy for composite nationalism and a uni ...

gathered in Delhi in April 1940 to voice its support for an independent and united India. Its members included several Islamic organisations in India, as well as 1400 nationalist Muslim delegates. The pro-separatist All-India Muslim League worked to try to silence those nationalist Muslims who stood against the partition of India, often using "intimidation and coercion". The murder of the All India Azad Muslim Conference leader Allah Bakhsh Soomro also made it easier for the All-India Muslim League to demand the creation of a Pakistan.

In January 1946, a number of mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with that of RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain. The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and Karachi. Although the mutinies were rapidly suppressed, they found much public support in India and had the effect of spurring the new Labour government in Britain to action, and leading to the Cabinet Mission to India led by the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, and including Sir Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

, who had visited four years before.

Also in early 1946, new elections were called in India in which the Congress won electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces. However, the negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League stumbled over the issue of the partition. Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946, Direct Action Day

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946), also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hinduism in India, Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) ...

, with the stated goal of peacefully highlighting the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. The following day, Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Calcutta and they quickly spread throughout India. Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September, a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

serving as united India's prime minister.

Later that year, the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, decided to end British rule of India, and in early 1947, Britain announced its intention to transfer power no later than June 1948.

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued unabated. With the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence. In June 1947, the nationalist leaders, including Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following In ...

on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah representing the pro-separatist Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956) was an Indian jurist, economist, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India from the Constituent Assembly debates, served ...

representing the Untouchable community, and Master Tara Singh

Master Tara Singh (24 June 1885 – 22 November 1967) was an Indian Sikh political and religious figure in the first half of the 20th century. He was instrumental in organising the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee and guiding the Sikh ...

representing the Sikhs, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. In the years leading up to the partition of India, the pro-separatist All-India Muslim League violently drove out Hindus and Sikhs from the western Punjab.

Many millions of Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu refugees trekked across the newly drawn borders. In Punjab, where the new border lines divided the Sikh regions in half, massive bloodshed followed; in Bengal and Bihar, where Gandhi's presence assuaged communal tempers, the violence was more limited. In all, anywhere between 250,000 and 500,000 people on both sides of the new borders died in the violence. On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor General in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former c ...

. The following day, 15 August 1947, India, now a smaller ''Union of India'', became an independent country with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi, with Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

, and the viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, stayed on as its first Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

.

See also

*British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

* Company rule in India

Company rule in India (sometimes, Company ''Raj'', from hi, rāj, lit=rule) refers to the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when ...

* British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

Notes

Surveys and reference books

*. *. *. * Buckland, C.E. ''Dictionary of Indian Biography'' (1906) 495pfull text

*. *. * *. * *. *. *. * Rees, Rosemary. ''India 1900–47'' (Heineman, 2006), textbook. * Riddick, John F. ''Who Was Who in British India'' (1998); 5000 entrie

excerpt

*. *. *. *. *.

Monographs and collections

*. * * *. *. * Gilmartin, David. 1988. ''Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan''. Berkeley: University of California Press. 258 pages. . *. *. *. * * * *. *. *. * * * * * Shaikh, Farzana. 1989. ''Community and Consensus in Islam: Muslim Representation in Colonial India, 1860—1947''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 272 pages. . *. *.Articles in journals or collections

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *. * * * *Classic Histories and Gazetteers

* * *. *.Tertiary Sources

*. *{{Citation , last1=Wolpert , first1=Stanley , chapter=India: British Imperial Power 1858–1947 (Indian nationalism and the British response, 1885–1920; Prelude to Independence, 1920–1947) , chapter-url=https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-47042/India , year=2007 , title=Encyclopædia Britannica .External links

* Encyclopedia of India British India