History of the African-Americans in Philadelphia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This article documents the history of African-Americans or Black Philadelphians in

This article documents the history of African-Americans or Black Philadelphians in

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

During the

During the

. "African American Migration"

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2021. In 1896 Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel Iola Leroy. Published in 1899 by the

World War I brought an influx of black migrants from the rural South, who moved to Philadelphia lured by wartime jobs there during The great migration. As a result, the black population of Philadelphia doubled again from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920.Most of the new residents came from rural backgrounds and were working poor.

Efforts to build new structures to house the workers were insufficient, so African Americans in search of housing moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods, where they encountered hostility and racism. In July 1918, after two black families on Pine Street were attacked by white neighbors who burned household furnishings, G. Grant Williams, editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, wrote of the “Pine Street war Zone”: “We stand for peace,” he said, and advised Black residents to “stand your ground like men,” adding “You are not down in Dixie now and you need not fear the ragged rum crazed hellion crew... They may burn your property, but you burn their hides with any weapon that comes handy while they engage in this illegal pastime.”

Three weeks later, racial violence erupted again which lasted for several days. During the riot, black homes were destroyed by white mobs, three people were killed, one man was nearly lynched, and a white police officer beat up a black man while he was in the hospital. As a result, African Americans in Philadelphia formed the Colored Protective Association, led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., to “have a permanent organization of protection” to fight discrimination in schools, housing, employment and elsewhere, and to investigate cases of police brutality and police collusion with the white rioters. Their efforts eventually led to the removal of the entire police force by the Director of Public Safety.

World War I brought an influx of black migrants from the rural South, who moved to Philadelphia lured by wartime jobs there during The great migration. As a result, the black population of Philadelphia doubled again from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920.Most of the new residents came from rural backgrounds and were working poor.

Efforts to build new structures to house the workers were insufficient, so African Americans in search of housing moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods, where they encountered hostility and racism. In July 1918, after two black families on Pine Street were attacked by white neighbors who burned household furnishings, G. Grant Williams, editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, wrote of the “Pine Street war Zone”: “We stand for peace,” he said, and advised Black residents to “stand your ground like men,” adding “You are not down in Dixie now and you need not fear the ragged rum crazed hellion crew... They may burn your property, but you burn their hides with any weapon that comes handy while they engage in this illegal pastime.”

Three weeks later, racial violence erupted again which lasted for several days. During the riot, black homes were destroyed by white mobs, three people were killed, one man was nearly lynched, and a white police officer beat up a black man while he was in the hospital. As a result, African Americans in Philadelphia formed the Colored Protective Association, led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., to “have a permanent organization of protection” to fight discrimination in schools, housing, employment and elsewhere, and to investigate cases of police brutality and police collusion with the white rioters. Their efforts eventually led to the removal of the entire police force by the Director of Public Safety.

In 1925, the artist and printmaker

In 1925, the artist and printmaker

The fight against discrimination and segregation in education and employment continued through the 1950s and 60s, with legal battles and protests occurring throughout those years.

The fight against discrimination and segregation in education and employment continued through the 1950s and 60s, with legal battles and protests occurring throughout those years.  Philadelphia soul was a genre of music that arose in the late 1960s and 70s. Influenced by funk, it was characterized by lush instrumental arrangements with sweeping strings and piercing horns. Fred Wesley described it as “putting the bow tie on funk”. It moved funk more towards the disco sound that would become popular in the late 1970s and influenced later Philadelphia-born music makers like singer Jill Scott.

Predominently Black group MOVE was founded in 1972 by

Philadelphia soul was a genre of music that arose in the late 1960s and 70s. Influenced by funk, it was characterized by lush instrumental arrangements with sweeping strings and piercing horns. Fred Wesley described it as “putting the bow tie on funk”. It moved funk more towards the disco sound that would become popular in the late 1970s and influenced later Philadelphia-born music makers like singer Jill Scott.

Predominently Black group MOVE was founded in 1972 by

The

The

Aces Museum

honors WWII veterans and their families. Th

Colored Girls Museum

founded by Vashti DuBois, is dedicated to the history of Black women and girls. Th

National Marian Anderson Museum

celebrates the life of the notable opera singer

The

The

''A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten''

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 16. *

This article documents the history of African-Americans or Black Philadelphians in

This article documents the history of African-Americans or Black Philadelphians in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

.

Recent 2010 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

put the total number of people living in Philadelphia who identify as Black or African-American at 644,287, or 42.2% of the city's total population. People of African descent are currently the largest ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

in Philadelphia. Originally arriving in the 17th century as enslaved Africans, the population of African Americans in Philadelphia grew in the 18th and 19th centuries to include numerous free black residents who were active in the abolitionist movement and as conductors in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Black Philadelphians actively campaigned against discrimination and continued to contribute to Philadelphia's cultural, economic and political life as workers, activists, artists, musicians and politicians.

History

1639 to 1800

Enslaved Africans arrived in the area that becamePhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

as early as 1639, brought by European settlers. In the 1750s and 60s, when the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

increased due to a shortage of European workers, 100 to 500 Africans came to Philadelphia each year. In 1765, there were about fifteen hundred black Philadelphians; of these, one hundred were free. By the time the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

broke out in 1775, slaves were one-twelfth of the roughly 16,000 people who lived in Philadelphia./

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Two on the American side were Cyrus Bustill

Cyrus Bustill (February 2, 1732 1806) was an African-American brewer and baker, abolitionist and community leader.

A notable business owner in the African-American community in Philadelphia, he also became a founding member of the Free African ...

, who worked as a ship's baker during the Revolution and later became a prominent Philadelphia businessman and activist, and James Forten, who served on a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

at the age of 14 and became a wealthy sailmaker and abolitionist. Some slaves were freed by their owners and others managed to escape or buy their own freedom. As a result, the free Black community in Philadelphia had grown to over 1,000 by the end of the Revolution in 1783, while enslaved residents numbered 400. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded by white Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

in 1775 and eventually became a biracial organization.

In 1780 a policy of gradual emancipation was instituted in Pennsylvania.

The Quakers immediately established a Burying Place For All Free Negroes or People of Color in Byberry Township. This African Burial Ground remains an obscure anomaly, forgotten today much the same as the day it was placed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. Most of the Black population in Philadelphia were free by 1811, although some remained enslaved until the 1840s. The free community was joined by runaways from the South and refugees from the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on ...

.

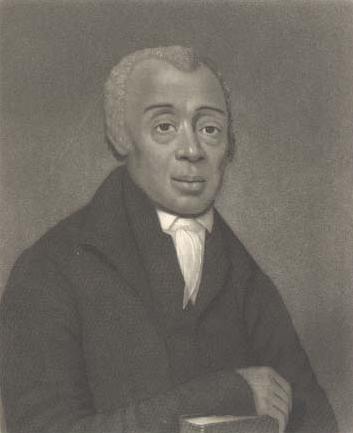

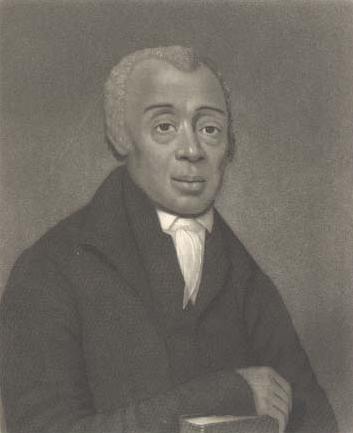

Richard Allen and Absolom Jones founded the Free African Society in 1787, a mutual aid society, and Allen, with his wife Sarah Allen

Sarah Allen is a Canadian actress. She studied acting at the National Theatre School of Canada and graduated in 2002.

''Being Human''

Allen is perhaps best known for playing vampire Rebecca Flynt on SyFy

Syfy (formerly Sci-Fi Channel ...

, established the Bethel African Methodist Church in 1794. During the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic, Black residents were mistakenly believed to be immune to the disease, so they worked as carriers of the dead and tended to the sick and dying inside their homes. Kidnapping of free Black residents to be sold back into slavery was a risk that continued into the 19th century, especially for children.

1800 to Civil War

The growing free Black community was instrumental in making Philadelphia a hotbed ofabolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

by the 1830s. Wealthy Black entrepreneur James Forten gave white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

funding so he could start the anti-slavery newspaper '' The Liberator'' and contributed articles to it. Black activists were founders and members of the national biracial group the American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this socie ...

, created in Philadelphia in 1833, and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, created in 1838. In December 1833, after women were excluded from the American Anti-Slavery Society, a group of black and white women, which included Cyril Bustil's daughter Grace Douglass, and James Forten's daughters, Sarah, Harriet and Margaretta launched the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) was founded in December 1833 and dissolved in March 1870 following the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was founded by eighteen women, including Mary ...

(PFASS).

While some African Americans in Philadelphia worked in professional jobs that catered to the Black community like teachers, doctors, ministers, barbers, caterers, and entrepreneurs, most Black Philadelphians at that time worked at physically demanding and low-paying jobs. They competed with working class whites, especially new Irish immigrants, for jobs, which led to racial conflict. In 1834, a race riot broke started at a local tavern that was popular with both black and white Philadelphians. A white mob attacked Black homes, businesses, and churches. In 1838, another white mob attacked Pennsylvania Hall, where black and white abolitionists were meeting, and burned it down. Also in 1838, Pennsylvania's newly ratified constitution officially disfranchised African Americans. In 1842, white mobs again attacked blacks during the Lombard Street Riots.

Despite the risks and racism they encountered, African-Americans continued to come to Philadelphia, since it was the closest major city to the Southern States, where slavery was still legal. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Philadelphia had the largest black population outside the slave states. There were 15,000 black Philadelphians in 1830, 20,000 by 1850, and 22,000 by 1860. Most lived in South Philadelphia near what is today Center City, but there were smaller populations in Northern Liberties, Kensington, and Spring Garden. They came because of Philadelphia's reputation as a thriving political, cultural, and economic center for African Americans.

The city was also a major stop on the Underground Railroad, especially for slaves escaping through Maryland and Delaware. Robert Purvis

Robert Purvis (August 4, 1810 – April 15, 1898) was an American abolitionist in the United States. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and was likely educated at Amherst Academy, a secondary school in Amherst, Massachusetts. He s ...

, president of the biracial Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society from 1845–50, was also chairman of the General Vigilance Committee

A vigilance committee was a group formed of private citizens to administer law and order or exercise power through violence in places where they considered governmental structures or actions inadequate. A form of vigilantism and often a more stru ...

from 1852–1857, which gave direct aid to fugitive slaves. With his wife Harriet Forten Purvis, he worked as a conductor of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. Purvis estimated that from 1831–61, they helped one slave per day achieve freedom, assisting more than 9,000 slaves to escape to the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

. They used their own house, then located outside the city, in Byberry Township, as a place where fugitives could hide. Purvis built Byberry Hall across the street from his home, on the edge of the Quaker-owned Byberry Friends Meeting campus, to host anti-slavery speakers. It still stands today.

Civil War to 1900

During the

During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, eleven African American Philadelphia regiments fought for the North, after the passage of the

1862 Second Militia Act allowing blacks to be enlist in the Army.

After the Civil War, African Americans in Philadelphia, including Octavius V. Catto (1839–71), organized to end segregation of the city’s schools and streetcars and regain the right to vote. Their efforts paid off; in 1867, streetcar segregation was ended throughout the state, and legal segregation of schools ended in 1881 (although de facto segregation continued into the 20th century.) The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave Pennsylvania Black Americans the right to vote in 1870. But Catto himself was shot and killed while trying to cast his ballot in 1871.

In 1879, painter Henry Ossawa Tanner enrolled as the first African American student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. After travels abroad, he would return to Philadelphia in 1893 to paint his most famous work, The Banjo Lesson. Also in 1893, Philadelphia high school student Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller created an art project that was included in The World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and led to her future success as a multi-disciplinary artist.

The Black population rose to nearly 32,000 in 1880. In 1884, there were approximately 300 black-owned businesses, including the Philadelphia Tribune (started in 1884) and Douglas Hospital (opened in 1895). By 1900, the Black population at 63,000 people, had nearly doubled.Wolfinger, Jame. "African American Migration"

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2021. In 1896 Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel Iola Leroy. Published in 1899 by the

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest- ...

and conducted by W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up i ...

, '' The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study'' was the first sociological race study of the African American community in the United States''.'' The aim of the social study was to identify "The Negro Problems of Philadelphia," the problems facing black communities not only in Philadelphia, but all over the country as well. The study focused on Philadelphia's Seventh Ward (currently Center City Philadelphia) and the socioeconomic conditions of black churches, businesses and homes within the neighborhood. Using statistics

Statistics (from German: '' Statistik'', "description of a state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a scientific, indust ...

Du Bois created from his survey data, Du Bois compared the occupation, income, education, family size, health, drug use, criminal activity, and suffrage of black and white residents living in the Seventh Ward and to Philadelphia's other wards. Du Bois used statistical evidence to highlight the socioeconomic inequalities the black community faced and make the black community's suffrage known to whites. In turn, he disproved stereotypes surrounding the black community which were cited as the sources of "The Negro Problem."

1900 to 1950s

World War I brought an influx of black migrants from the rural South, who moved to Philadelphia lured by wartime jobs there during The great migration. As a result, the black population of Philadelphia doubled again from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920.Most of the new residents came from rural backgrounds and were working poor.

Efforts to build new structures to house the workers were insufficient, so African Americans in search of housing moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods, where they encountered hostility and racism. In July 1918, after two black families on Pine Street were attacked by white neighbors who burned household furnishings, G. Grant Williams, editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, wrote of the “Pine Street war Zone”: “We stand for peace,” he said, and advised Black residents to “stand your ground like men,” adding “You are not down in Dixie now and you need not fear the ragged rum crazed hellion crew... They may burn your property, but you burn their hides with any weapon that comes handy while they engage in this illegal pastime.”

Three weeks later, racial violence erupted again which lasted for several days. During the riot, black homes were destroyed by white mobs, three people were killed, one man was nearly lynched, and a white police officer beat up a black man while he was in the hospital. As a result, African Americans in Philadelphia formed the Colored Protective Association, led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., to “have a permanent organization of protection” to fight discrimination in schools, housing, employment and elsewhere, and to investigate cases of police brutality and police collusion with the white rioters. Their efforts eventually led to the removal of the entire police force by the Director of Public Safety.

World War I brought an influx of black migrants from the rural South, who moved to Philadelphia lured by wartime jobs there during The great migration. As a result, the black population of Philadelphia doubled again from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920.Most of the new residents came from rural backgrounds and were working poor.

Efforts to build new structures to house the workers were insufficient, so African Americans in search of housing moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods, where they encountered hostility and racism. In July 1918, after two black families on Pine Street were attacked by white neighbors who burned household furnishings, G. Grant Williams, editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, wrote of the “Pine Street war Zone”: “We stand for peace,” he said, and advised Black residents to “stand your ground like men,” adding “You are not down in Dixie now and you need not fear the ragged rum crazed hellion crew... They may burn your property, but you burn their hides with any weapon that comes handy while they engage in this illegal pastime.”

Three weeks later, racial violence erupted again which lasted for several days. During the riot, black homes were destroyed by white mobs, three people were killed, one man was nearly lynched, and a white police officer beat up a black man while he was in the hospital. As a result, African Americans in Philadelphia formed the Colored Protective Association, led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., to “have a permanent organization of protection” to fight discrimination in schools, housing, employment and elsewhere, and to investigate cases of police brutality and police collusion with the white rioters. Their efforts eventually led to the removal of the entire police force by the Director of Public Safety.

In 1925, the artist and printmaker

In 1925, the artist and printmaker Dox Thrash

Dox Thrash (1893–1965) was an African-American artist who was famed as a skilled draftsman, master printmaker, and painter and as the co-inventor of the Carborundum printmaking process.Donnelly, Michell"The Art of Dox Thrash" The Encyclopedia o ...

moved to Philadelphia, where he would spend most of his career. Black Opals

''Black Opals'' was an African American literary journal published in Philadelphia between spring 1927 and July 1928, associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Co-founded by Arthur Huff Fauset and Nellie Rathbone Bright, the magazine's contributor ...

, an African American literary magazine associated with the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

was published in Philadelphia between spring 1927 and July 1928,. Co-edited by Arthur Huff Fauset and Nellie Rathbone Bright, the magazine's contributors included Mae Virginia Cowdery, Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an African-American editor, poet, essayist, novelist, and educator. Her literary work helped sculpt African-American literature in the 1920s as she focused on portraying a true image ...

, Marita Bonner

Marita Bonner (June 16, 1899 – December 7, 1971), also known as Marieta Bonner, was an American writer, essayist, and playwright who is commonly associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Other names she went by were Marita Occomy, Marita Odette ...

, and Gwendolyn B. Bennett

Gwendolyn B. Bennett (July 8, 1902 – May 30, 1981) was an American artist, writer, and journalist who contributed to '' Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life'', which chronicled cultural advancements during the Harlem Renaissance. Though often ...

. Allan Randall Freelon was the magazine's artistic director. Also in the 1920s, John T Gibson became the wealthiest Black entrepreneur in Philadelphia because of his ownership of the popular Standard and Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and gave its name to an ...

theaters and his management of diverse musical and vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

acts.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

hit Black Philadelphians hard. By 1933, 50% of all Black residents were unemployed. And yet by 1935, African Americans owned 9,855 homes and 787 stores; they were also working in more professional occupations, like physicians ( 200); clergymen ( 250); schoolteachers (553) and policemen ( 219). Their neighborhoods were also becoming more concentrated and more segregated from white neighborhoods.

In 1938, Crystal Bird Fauset became the first female African American elected as state legislator.

Though World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

brought wartime jobs to African Americans, they still faced substandard housing and were not allowed to work on Philadelphia public transit as motormen or conductors until the Federal Government stepped in to pressure the Philadelphia Transportation Company

The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) was the main public transit operator in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1940 to 1968. A private company, PTC was the successor to the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT), in operation since 1 ...

to open up these jobs to them in 1944. From August 1–6, white transit workers responded by staging a massive sickout strike. After pressure from the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

, the Federal Government sent in 5,000 troops to break the strike and keep public transportation running.

Philadelphia was a center for the mid twentieth century Golden Age of Gospel music

Gospel music is a traditional genre of Christian music, and a cornerstone of Christian media. The creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of gospel music varies according to culture and social context. Gospel music is co ...

, attracting performers like the nationally renowned male quartets the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Sensational Nightingales

The Sensational Nightingales are a traditional black gospel quartet that reached its peak of popularity in the 1950s, when it featured Julius Cheeks as its lead singer. The Nightingales, with several changes of membership, continue to tour and r ...

, as well as Marion Willliams before she started her solo career.

1950s to Present

The fight against discrimination and segregation in education and employment continued through the 1950s and 60s, with legal battles and protests occurring throughout those years.

The fight against discrimination and segregation in education and employment continued through the 1950s and 60s, with legal battles and protests occurring throughout those years. Cecil B. Moore

Cecil Bassett Moore (April 2, 1915 – February 13, 1979) was a Philadelphia lawyer, politician and civil rights activist who led the fight to integrate Girard College, president of the local NAACP, and member of Philadelphia's city council ...

, president of the local NAACP, was a leading activist during that time, and Reverend Leon Sullivan

Leon Howard Sullivan (October 16, 1922 – April 24, 2001) was a Baptist minister, a civil rights leader and social activist focusing on the creation of job training opportunities for African Americans, a longtime General Motors Board Member, an ...

was instrumental in building Black community and economic power. Marie Hicks successfully organized demonstrations and brought a lawsuit against Girard College to desegregate that institution. In 1964, a clash between police officers and residents sparked a three day riot.

The Sixties saw a rise in the Black Power movement in Philadelphia. Freedom Library on Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia, started in 1964 by John Churchville, was where Churchville and other activists gathered to form the Black Power Unity Movement in 1965. Another important center of Black Power was The Church of the Advocate in North Central Philadelphia, whose congregation had become increasingly African American. Father Paul Washington organized the first Black Power rally in 1966; soon there were rallies all over the city, and the third national conference in Philadelphia attracted 2,000 people. The newspaper ''Voice of Umuja'' came out of the conference.

Reggie Schell became the leader of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxism-Leninism, Marxist-Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. New ...

in 1969. Under his leadership, the party held rallies and created food distribution and education programs throughout the city. Black Power spilled onto college and high school campuses, where students demonstrated for more Black faculty and Black studies classes. In 1970, Philadelphia police raids of three offices of Black Power activists at gunpoint, in which they publicly strip searched activists, made international news for their brutality and united the black community in outrage. Later that year, the Panther sponsored Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention was held at Temple College and attracted 14,000 people.

Philadelphia soul was a genre of music that arose in the late 1960s and 70s. Influenced by funk, it was characterized by lush instrumental arrangements with sweeping strings and piercing horns. Fred Wesley described it as “putting the bow tie on funk”. It moved funk more towards the disco sound that would become popular in the late 1970s and influenced later Philadelphia-born music makers like singer Jill Scott.

Predominently Black group MOVE was founded in 1972 by

Philadelphia soul was a genre of music that arose in the late 1960s and 70s. Influenced by funk, it was characterized by lush instrumental arrangements with sweeping strings and piercing horns. Fred Wesley described it as “putting the bow tie on funk”. It moved funk more towards the disco sound that would become popular in the late 1970s and influenced later Philadelphia-born music makers like singer Jill Scott.

Predominently Black group MOVE was founded in 1972 by John Africa

John Africa (July 26, 1931 – May 13, 1985), born Vincent Leaphart, was the founder of MOVE, a Philadelphia-based, predominantly black organization active from the early 1970s and still active. He and his followers were killed at a residential ...

. The organization lived in a communal setting in West Philadelphia, following philosophies of anarcho-primitivism. In 1978, a standoff between MOVE and the Philadelphia police resulted in the death of one police officer and injuries to sixteen officers and firefighters. Nine members were convicted of killing the officer and received life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes ...

s. In 1985, another conflict resulted in a police helicopter dropping a bomb onto the roof of the MOVE compound, a townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type of city residence ...

that was located at 6221 Osage Avenue. The ensuing fire killed six MOVE members, and five of their children, and destroyed sixty-five houses in the neighborhood. The police bombing was strongly condemned. The MOVE survivors later filed a civil suit

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil act ...

against the City of Philadelphia and the PPD and were awarded $1.5 million in a 1996 settlement. Other residents displaced by the destruction of the bombing filed a civil suit against the city and in 2005 were awarded $12.83 million in damages in a jury trial.

In 1982, Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Philadelphia activist and journalist, was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1981 murder in Philadelphia of police officer Daniel Faulkner. He became widely known while on death row for his writings and commentary on the U.S. criminal justice system. After numerous appeals, his death penalty sentence was overturned by a Federal court, with the prosecution agreeing in 2011 to a sentence of life imprisonment without parole.

Many Philadelphia activists of the mid to late 20th century went on to achieve political power. In 1975, Cecile B. Moore won a seat on the City Council. C. Delores Tucker

Cynthia Delores Tucker (née Nottage; October 4, 1927 – October 12, 2005) was an American politician and civil rights activist. She had a long history of involvement in the American Civil Rights Movement. From the 1990s onward, she engaged in a ...

(1927-2005) became the first black Pennsylvanian appointed to the office of the secretary of state. David P. Richardson (1948-1995) was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1972. In 1984, W. Wilson Goode

Woodrow Wilson Goode Sr. (born August 19, 1938) is a former Mayor of Philadelphia and the first African American to hold that office. He served from 1984 to 1992, a period which included the controversial MOVE police action and house bombing ...

(b. 1938) became Philadelphia’s first black mayor. Goode’s administration was followed by black mayors John Street (b. 1943) and Michael Nutter (b. 1957).

Despite the persistence of problems like unemployment and high public school dropout rates, the black community in Philadelphia in the early 21st century continued to attract new residents and contribute its talents and energy to the city. In 2010, its total population stood at 657,343 people or 43.4 percent of Philadelphia's entire population.

Institutions

The

The African American Museum in Philadelphia

The African American Museum in Philadelphia (AAMP) is notable as the first museum funded and built by a municipality to help preserve, interpret and exhibit the heritage of African Americans. Opened during the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations, th ...

is located in Center City.

ThAces Museum

honors WWII veterans and their families. Th

Colored Girls Museum

founded by Vashti DuBois, is dedicated to the history of Black women and girls. Th

National Marian Anderson Museum

celebrates the life of the notable opera singer

Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throughout the United ...

.

The Paul Robeson House hosts tours of Robeson's former residence.

Geography

20th century

Circa 1961 Society Hill was a majority black and low income neighborhood, but by 1976 it became gentrified and mostly white with the remaining black population residing in about three or four high-rise apartment buildings with high rents. '' Black Enterprise'' wrote that a possible reason why wealthier blacks opted not to move to Society Hill was "Unpleasant memories of the old neighborhood". By then many blacks were moving to Wynnefield, with many originating from Cobbs Creek and Overbrook; the new residents of Wynnefield had recently become middle class."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 44. Also Circa 1976 many African-Americans resided inPowelton Village

Powelton Village is a neighborhood of mostly Victorian, mostly twin homes in the West Philadelphia section of the United States city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is a national historic district that is part of University City. It extends ...

. The majority originated from other states and held professional positions, including artists, graduate students, musicians, teachers, and writers.

21st century

From 1990 to 2010, Black residents moved in significant numbers away from the core areas of North and West Philadelphia to Southwest Philadelphia, Overbrook, the Lower Northeast, and elsewhere. The number of Black residents in zip code 19120—which includes the neighborhoods of Olney and Feltonville and abuts Montgomery County -rose from 9,786 in 1990 to 33,209 in 2010, an increase of 239 percent.Religion

The

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas (AECST) was founded in 1792 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the first black Episcopal Church in the United States. Its congregation developed from the Free African Society, a non-denominational group f ...

, established in 1792, was the first house of worship created by and for black people in the United States. While the St. George's United Methodist Church had initially allowed black worshipers in the main area, its black worshipers left after the church moved them to the gallery area by 1787."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 36.

Education

The first school for Black males was established by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1794. In 1813, the Society constructed the school building Clarkson Hall on Cherry Street, and in 1854, created Lombard Street Infant School as an aid to working parents. In 1976 66% of all students of theSchool District of Philadelphia

The School District of Philadelphia (SDP) is the school district that includes all school district-operated public schools in Philadelphia. Established in 1818, it is the 8th largest school district in the nation, by enrollment, serving over 200 ...

were black; this number was proportionally high since whites of all economic backgrounds had a tendency to use private schools. Wealthier blacks chose not to use private schools because their neighborhoods were assigned to higher quality public schools.

Notable residents

18th–19th centuries

* Richard Allen, religious leader, author, journalist *Sarah Allen

Sarah Allen is a Canadian actress. She studied acting at the National Theatre School of Canada and graduated in 2002.

''Being Human''

Allen is perhaps best known for playing vampire Rebecca Flynt on SyFy

Syfy (formerly Sci-Fi Channel ...

, abolitionist, underground railroad conductor, missionary

* Cyrus Bustill

Cyrus Bustill (February 2, 1732 1806) was an African-American brewer and baker, abolitionist and community leader.

A notable business owner in the African-American community in Philadelphia, he also became a founding member of the Free African ...

, 18th century entrepreneur, abolitionist and community leader

* Jabez Pitt Campbell, abolitionist, and the 8th Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. ...

* Amy Matilda Cassey

Amy Matilda Williams Cassey (August 14, 1809–August 15, 1856) was an African American abolitionist, and was active with the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Cassey was a member of the group of elite African Americans who founded the Gil ...

, activist, and abolitionist

* Joseph Cassey

Joseph Cassey (1789–1848) was a French West Indies-born American businessman, real estate investor, abolitionist, and activist. He prospered as a barber, and as well as a wig maker, perfumer, and money-lender. He lived in the historic Cassey H ...

, businessman, abolitionist, and activist

* Octavius Catto

Octavius Valentine Catto (February 22, 1839 – October 10, 1871) was an educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist in Philadelphia. He became principal of male students at the Institute for Colored Youth, where he had also been educated ...

, educator and Civil Rights activist

* Rebecca Cole

Rebecca J. Cole (March 16, 1846August 14, 1922) was an American physician, organization founder and social reformer. In 1867, she became the second African-American woman to become a doctor in the United States, after Rebecca Lee Crumpler thre ...

, doctor and social reformer

* Rebecca Cox Jackson, founder of a Shaker community in Philadelphia

* Nathaniel W. Depee, activist, and abolitionist

* Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, social reformer, writer, and abolitionist

* Charlotte Vandine Forten

Charlotte Vandine Forten (1785–1884) was an American abolitionist and matriarch of the Philadelphia Forten family.

Biography

Forten née Vandine was born in 1785 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1805 she married James Forten (1766–184 ...

, abolitionist

* James Forten, early 19th century businessman and abolitionistWinch, Julie,''A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten''

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 16. *

Margaretta Forten

Margaretta Forten (September 11, 1806 – January 13, 1875) was an African-American suffragist and abolitionist.Alexander, Leslie''Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1''ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 1045.Alexander, Leslie

''Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1''

ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 1045. * Grace Douglass, abolitionist * Sarah Mapps Douglass, 19th century educator *

''Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1''

ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 1045. * Grace Douglass, abolitionist * Sarah Mapps Douglass, 19th century educator *

Richard Theodore Greener

Richard Theodore Greener (1844–1922) was a pioneering African Americans, African-American scholar, excelling in elocution, philosophy, law and classics in the Reconstruction era. He broke ground as Harvard College's first Black graduate in 18 ...

, professor, lawyer, scholar

* Charlotte Forten Grimké

Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten Grimké (August 17, 1837 – July 23, 1914) was an African American anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. She grew up in a prominent abolitionist family in Philadelphia. She taught school for years, including d ...

, 19th century civil rights activist, woman's rights activist

* Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1845, she was one of the first African-American women ...

, abolitionist, suffragette, poet, author

* Jarena Lee

Jarena Lee (February 11, 1783 – February 3, 1864) was the first woman preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). Born into a free Black family, in New Jersey, Lee asked the founder of the AME church, Richard Allen, to be a preac ...

, preacher

* Absalom Jones, minister, abolitionist, and founder of Free African Society

* John McKee John McKee may refer to:

* John McKee (politician) (1771–1832), American politician

* John McKee (American football) (1877–1950), American football coach and physician

* John McKee (philanthropist) (1821–1902), African-American property magnat ...

, philanthropist, property owner

* Zedekiah Johnson Purnell, activist, and businessman

* Harriet Forten Purvis, abolitionist

* Robert Purvis

Robert Purvis (August 4, 1810 – April 15, 1898) was an American abolitionist in the United States. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and was likely educated at Amherst Academy, a secondary school in Amherst, Massachusetts. He s ...

, abolitionist, lived most of his life in Philadelphia

* Sarah Louisa Forten Purvis

Sarah Louisa Forten Purvis (1814–1884) was an American poet and abolitionist from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She co-founded The ''Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society'' and contributed many poems to the anti-slavery newspaper ''The Libe ...

, abolitionist, suffragist

* William B. Purvis

William B. Purvis (12 August 1838 – 10 August 1914) was an African-American inventor and businessman who received multiple patents in the late 19th-century. His inventions included improvements on paper bags, an updated fountain pen design, impr ...

, inventor and businessman

* Stephen Smith, businessman, philanthropist, preacher, real estate developer, and abolitionist

* William Whipper

William Whipper (February 22, 1804 – March 9, 1876) was a businessman and abolitionist in the United States. Whipper, an African American, advocated nonviolence and co-founded the American Moral Reform Society, an early African-American aboli ...

, businessman and abolitionist

* Peter Williams Jr.

Peter Williams Jr. (1786–1840) was an African-American Episcopal priest, the second ordained in the United States and the first to serve in New York City. He was an abolitionist who also supported free black emigration to Haiti, the black republ ...

, pastor and abolitionist

20th–21st centuries

* Julian Abele, architect * Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, artist * Henry Ossawa Tanner, painter *Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1894 – September 26, 1937) was an American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the " Empress of the Blues", she was the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. Inducted into the Rock an ...

, blues singer and actress

* Alain LeRoy Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical archite ...

, Harlem Renaissance philosopher, journalist, author, scholar

* Raymond Pace Alexander, Lawyer and civil rights activist

* Rex Stewart, cornetist/trumpeter, journalist, disk jockey, publisher

* Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop s ...

, singer

* Ethel Waters, Singer, comedienne and actress

* Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throughout the United ...

, contralto opera singer

* Crystal Bird Fausett, first African-American female state legislator (elected 1938)

* Kobe Bryant

Kobe Bean Bryant ( ; August 23, 1978 – January 26, 2020) was an American professional basketball player. A shooting guard, he spent his entire 20-year career with the Los Angeles Lakers in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Widely r ...

, basketball player

* Michael Nutter, Mayor of Philadelphia

The mayor of Philadelphia is the chief executive of the government of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as stipulated by the Charter of the City of Philadelphia. The current mayor of Philadelphia is Jim Kenney.

History

The first mayor of Philadelphia, ...

* John F. Street

John Franklin Street (born October 15, 1943) is an American politician and lawyer who served as the 97th Mayor of the City of Philadelphia. He was first elected to a term beginning on January 3, 2000, and was re-elected to a second term begin ...

, Mayor of Philadelphia

* Luckey Roberts, pianist and composer

* Teddy Pendergrass

Theodore DeReese Pendergrass (March 26, 1950 – January 13, 2010) was an American soul and R&B singer-songwriter. He was born in Kingstree, South Carolina. Pendergrass spent most of his life in the Philadelphia area, and initially rose to musi ...

, Singer, songwriter and drummer

* Ed Bradley, News correspondent

* Wilt Chamberlain, basketball player

* Will Smith

Willard Carroll Smith II (born September 25, 1968), also known by his stage name The Fresh Prince, is an American actor and rapper. He began his acting career starring as a fictionalized version of himself on the NBC sitcom '' The Fresh ...

, rapper, actor

* Guion S. Bluford, astronaut, scientist, pilot

* Kevin Hart

Kevin Darnell Hart (born July 6, 1979) is an American comedian and actor. Originally known as a stand-up comedian, he has since starred in Hollywood films and on TV. He has also released several well-received comedy albums.

After winning se ...

, actor, comedian

* Patti LaBelle

Patricia Louise Holte (born May 24, 1944), known professionally as Patti LaBelle, is an American R&B singer, actress and businesswoman.

LaBelle is referred to as the " Godmother of Soul".

She began her career in the early 1960s as lead singe ...

, singer, actor

* Judith Jamison

Judith Ann Jamison (pronounced JAM-ih-son) (born May 10, 1943) is an American dancer and choreographer. She is the artistic director emerita of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Early training

Judith Jamison was born in 1943 to Tessie Brown Ja ...

, ballet dancer, choreographer

* Jill Scott, singer

* Sherman Hemsley, actor

* Solomon Burke

Solomon Vincent McDonald Burke (born James Solomon McDonald, March 21, 1936 or 1940 – October 10, 2010) was an American singer who shaped the sound of rhythm and blues as one of the founding fathers of soul music in the 1960s. He has been ...

, singer

* W. Wilson Goode

Woodrow Wilson Goode Sr. (born August 19, 1938) is a former Mayor of Philadelphia and the first African American to hold that office. He served from 1984 to 1992, a period which included the controversial MOVE police action and house bombing ...

, Mayor of Philadelphia

The mayor of Philadelphia is the chief executive of the government of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as stipulated by the Charter of the City of Philadelphia. The current mayor of Philadelphia is Jim Kenney.

History

The first mayor of Philadelphia, ...

* Mumia Abu-Jamal (born Wesley Cook)

* Bill Cosby, Comedian and actor

* Raymond Pace Alexander, lawyer, judge and politician

* Lil Uzi Vert

Symere Bysil Woods ( ; born July 31, 1995), known professionally as Lil Uzi Vert, is an American rapper, singer, and songwriter. They are characterized by their facial tattoos, facial piercings, eccentric hairstyles and androgynous fashion, im ...

, rapper

* Eve, rapper, singer, actress, and television presenter

* Meek Mill, rapper

* Beanie Sigel

Dwight Equan Grant (born March 6, 1974), better known by his stage name Beanie Sigel, is an American rapper from South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He first became known for his association with Jay-Z and Roc-A-Fella Records, releasing his debut ...

, rapper

See also

* Arch Street Friends Meeting House *Vigilant Association of Philadelphia

The Vigilant Association of Philadelphia was an abolitionist organization founded in August 1837 in Philadelphia to "create a fund to aid colored persons in distress". The initial impetus came from Robert Purvis, who had served on a previous '' ...

*Demographics of Philadelphia

At the 2010 census, there were 1,526,006 people, 590,071 households, and 352,272 families residing in the consolidated city-county of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The population density was 4,337.3/km2 (11,233.6/mi2). There were 661,958 housing u ...

* Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia

* History of the Jews in Philadelphia

* History of Irish Americans in Philadelphia

*History of Italian Americans in Philadelphia

Philadelphia has a significant Italian American population. In 2010, the Philadelphia metropolitan region had the second-largest Italian-American population in the United States with more than 142,000 residents with Italian ancestry, and about 3 ...

*African Americans in New York City

African Americans constitute one of the longer-running ethnic presences in New York City, home to the largest urban African American population, and the world's largest Black population of any city outside Africa, by a significant margin.

Pop ...

References

* "Blacks in Philadelphia." (November 1976). '' Black Enterprise''. Start p. 36.Notes

{{Portal bar, Philadelphia Ethnic groups in Philadelphia African-American cultural history History of Philadelphia