History of social democracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

originated as an ideology within the labour whose goals have been a social revolution to move away from purely laissez-faire capitalism to a social capitalism model sometimes called a social market economy

The social market economy (SOME; german: soziale Marktwirtschaft), also called Rhine capitalism, Rhine-Alpine capitalism, the Rhenish model, and social capitalism, is a socioeconomic model combining a free-market capitalist economic system alon ...

. In a nonviolent revolution

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution conducted primarily by unarmed civilians using tactics of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritarian ...

as in the case of evolutionary socialism, or the establishment and support of a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

. Its origins lie in the 1860s as a revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

associated with orthodox Marxism. Starting in the 1890s, there was a dispute between committed revolutionary social democrats such as Rosa Luxemburg and reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

social democrats. The latter sided with Marxist revisionists such as Eduard Bernstein, who supported a more gradual

The gradual ( la, graduale or ) is a chant or hymn in the Mass, the liturgical celebration of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, and among some other Christians. It gets its name from the Latin (meaning "step") because it was once chanted ...

approach grounded in liberal democracy and cross-class cooperation. Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels i ...

represented a centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to Left-w ...

position. By the 1920s, social democracy became the dominant political tendency, along with communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

, within the international socialist movement, representing a form of democratic socialism with the aim of achieving socialism peacefully. By the 1910s, social democracy had spread worldwide and transitioned towards advocating an evolutionary change from capitalism to socialism using established political processes such as the parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. In the late 1910s, socialist parties committed to revolutionary socialism renamed themselves as communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

, causing a split in the socialist movement between these supporting the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

and those opposing it. Social democrats who were opposed to the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

later renamed themselves as ''democratic socialists'' in order to highlight their differences from communists and later in the 1920s from Marxist–Leninists, disagreeing with the latter on topics such as their opposition to liberal democracy whilst sharing common ideological roots.

In the early post-war era, social democrats in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

rejected the Stalinist political and economic model, which was then current in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. They committed themselves either to an alternative path to socialism or to a compromise between capitalism and socialism. During the post-war period, social democrats embraced the idea of a mixed economy based on the predominance of private property, with only a minority of essential utilities

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and ...

and public services

A public service is any service intended to address specific needs pertaining to the aggregate members of a community. Public services are available to people within a government jurisdiction as provided directly through public sector agencies ...

being under public ownership

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownershi ...

. As a policy regime, social democracy became associated with Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output a ...

, state interventionism and the welfare state as a way to avoid capitalism's typical crises and to avert or prevent mass unemployment, without abolishing factor markets, private property and wage labour

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power under a ...

. With the rise in popularity of neoliberalism

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

and the New Right

New Right is a term for various right-wing political groups or policies in different countries during different periods. One prominent usage was to describe the emergence of certain Eastern European parties after the collapse of the Soviet Uni ...

by the 1980s, many social democratic parties incorporated the Third Way

The Third Way is a centrist political position that attempts to reconcile right-wing and left-wing politics by advocating a varying synthesis of centre-right economic policies with centre-left social policies. The Third Way was born from ...

ideology, aiming to fuse economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberali ...

with social democratic welfare policies. By the 2010s, social democratic parties that accepted triangulation and the neoliberal shift in policies such as austerity, deregulation, free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

and welfare reforms such as workfare

Workfare is a governmental plan under which welfare recipients are required to accept public-service jobs or to participate in job training. Many countries around the world have adopted workfare (sometimes implemented as "work-first" policies) to ...

, experienced a drastic decline. The Third Way largely fell out of favour in a phenomenon known as Pasokification. Scholars have linked the decline of social democratic parties to the declining number of industrial workers, greater economic prosperity of voters and a tendency for these parties to shift from the left to the centre

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

* Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentri ...

on economic issues. They alienated their former base of supporters and voters in the process. This decline has been matched by increased support for more left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

and left-wing populist

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often consists of anti- elitism, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking for the "com ...

parties, as well as for Left and Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a combi ...

social democratic parties that reject neoliberal and Third Way policies.

Social democracy was highly influential throughout the 20th century. Starting in the 1920s and 1930s, with the aftermath of World War I and that of the Great Depression, social democrats were elected to power. In countries such as Britain, Germany and Sweden, social democrats passed social reforms and adopted proto-Keynesian approaches that would be promoted across the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

in the post-war period, lasting until the 1970s and 1990s. Academics, political commentators and other scholars tend to distinguish between authoritarian socialist and democratic socialist states, with the first representing the Soviet Bloc and the latter representing Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

countries which have been democratically governed by socialist parties such as Britain, France, Sweden and Western social democracies in general, among others. Social democracy has been criticized by both the left and right. The left criticizes social democracy for having betrayed the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

during World War I and for playing a role in the failure of the proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...

1917–1924 revolutionary wave. It further accuses social democrats of having abandoned socialism. Conversely, one critique of the right is mainly related to their criticism of welfare. Another criticism concerns the compatibility of democracy and socialism.

Late 18th century to late 19th century

Revolutions and origins in the socialist movement (1793–1864)

The concept of social democracy goes back to theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

and the bourgeois-democratic Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, with historians such as Albert Mathiez seeing the French Constitution of 1793

The Constitution of 1793 (french: Acte constitutionnel du 24 juin 1793), also known as the Constitution of the Year I or the Montagnard Constitution, was the second constitution ratified for use during the French Revolution under the First Repu ...

as an example and inspiration whilst labelling Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

as the founding father of social democracy. The origins of social democracy as a working-class movement have been traced to the 1860s, with the rise of the first major working-class party in Europe, the General German Workers' Association

The General German Workers' Association (german: Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV) was a German political party founded on 23 May 1863 in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony by Ferdinand Lassalle. It was the first organized mass working-class ...

(ADAV) founded in 1863 by Ferdinand Lassalle. The 1860s saw the concept of social democracy deliberately distinguishing itself from that of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

. As Theodore Draper

Theodore H. Draper (September 11, 1912 – February 21, 2006) was an American historian and political writer. Draper is best known for the 14 books he completed during his life, including work regarded as seminal on the formative period of the Ame ...

explains in ''The Roots of American Communism'', there were two competing social democratic versions of socialism in 19th-century Europe, especially in Germany, where there was a rivalry over political influence between the Lassalleans

The General German Workers' Association (german: Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV) was a German political party founded on 23 May 1863 in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony by Ferdinand Lassalle. It was the first organized mass working-class ...

and the Marxists. Although the latter theoretically won out by the late 1860s and Lassalle had died early in 1864, in practice the Lassallians won out as their national-style social democracy and reformist socialism influenced the revisionist development of the 1880s and 1910s. The year 1864 saw the founding of the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

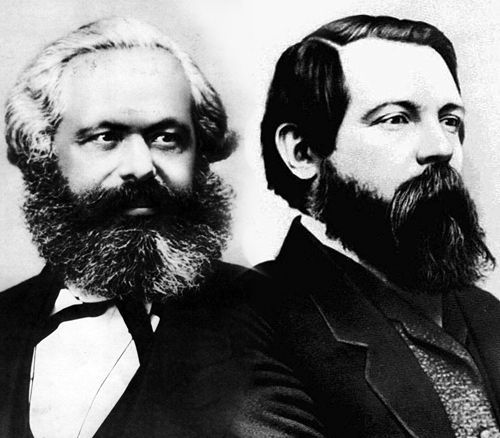

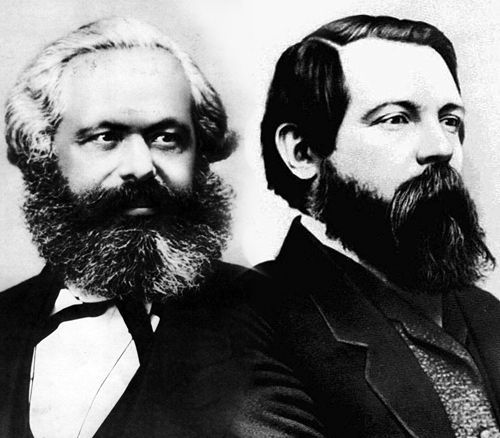

, also known as the First International. It brought together socialists of various stances and initially caused a conflict between Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and the anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, who were led by Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

, over the role of the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

in socialism, with Bakunin rejecting any role for the state. Another issue in the First International was the question of reformism and its role within socialism.

First International era, Lassalleans, and Marxists (1864–1889)

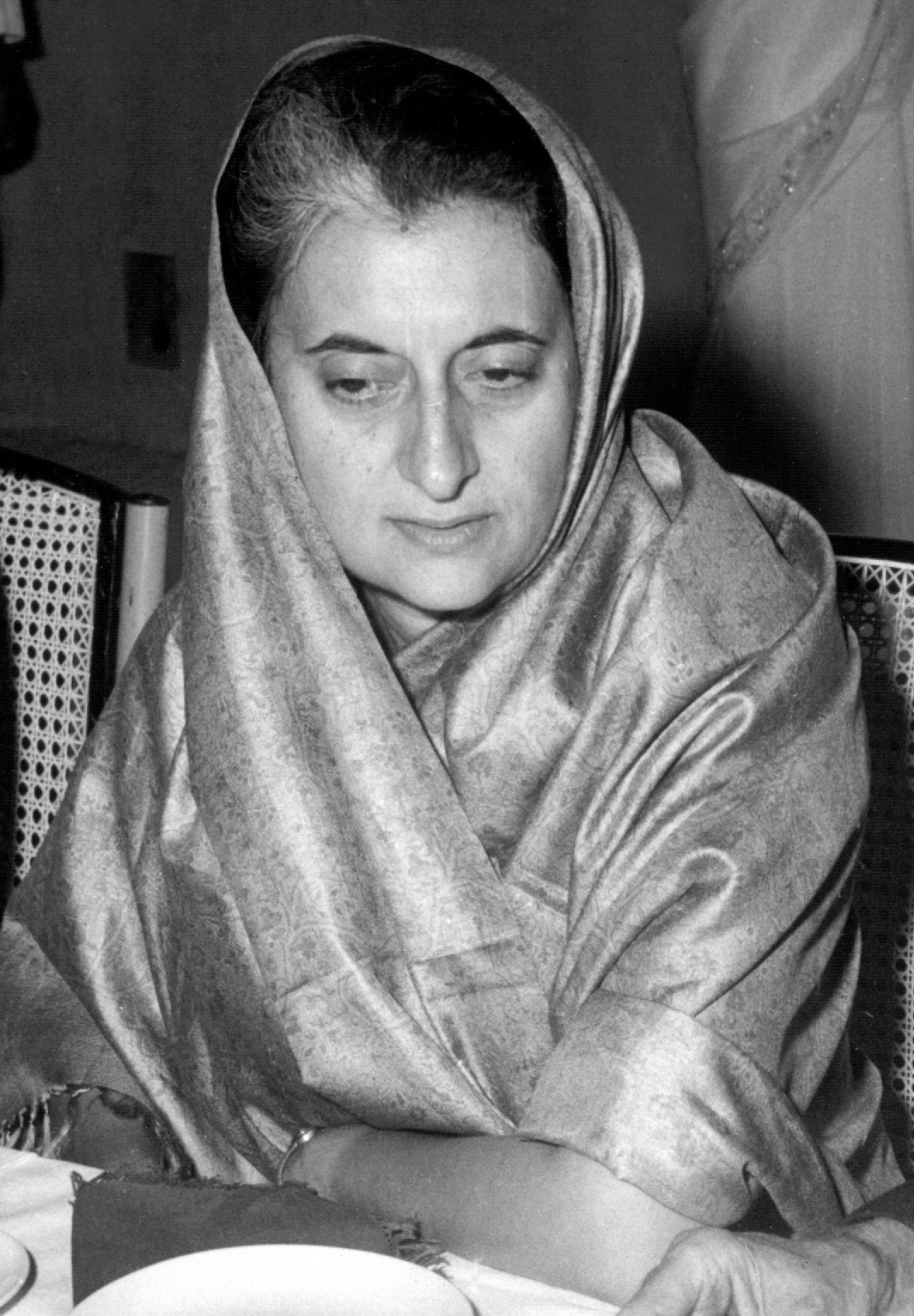

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' class struggle. Unlike Marx and Engels' '' Communist Manifesto'', Lassalle promoted class struggle in a more moderate form. While Marx's theory of the state saw it negatively as an instrument of class rule that should only exist temporarily upon the rise to power of the proletariat and then dismantled, Lassalle accepted the state. Lassalle viewed the state as a means through which workers could enhance their interests and even transform the society to create an economy based on worker-run cooperatives. Lassalle's strategy was primarily electoral and reformist, with Lassalleans contending that the working class needed a political party that fought above all for universal adult male suffrage. The ADAV's party newspaper was called '' The Social Democrat'' (german: Der Sozialdemokrat). Marx and Engels responded to the title ''Sozialdemocrat'' with distaste and Engels once writing: "But what a title: ''Sozialdemokrat''! ... Why do they not call the thing simply ''The Proletarian''". Marx agreed with Engels that ''Sozialdemokrat'' was a bad title. Although the origins of the name ''Sozialdemokrat'' actually traced back to Marx's German translation in 1848 of the Democratic Socialist Party (french: Partie Democrat-Socialist) into the Party of Social Democracy (german: link=no, Partei der Sozialdemokratie), Marx did not like this French party because he viewed it as dominated by the

The ADAV's party newspaper was called '' The Social Democrat'' (german: Der Sozialdemokrat). Marx and Engels responded to the title ''Sozialdemocrat'' with distaste and Engels once writing: "But what a title: ''Sozialdemokrat''! ... Why do they not call the thing simply ''The Proletarian''". Marx agreed with Engels that ''Sozialdemokrat'' was a bad title. Although the origins of the name ''Sozialdemokrat'' actually traced back to Marx's German translation in 1848 of the Democratic Socialist Party (french: Partie Democrat-Socialist) into the Party of Social Democracy (german: link=no, Partei der Sozialdemokratie), Marx did not like this French party because he viewed it as dominated by the

'' class struggle. Unlike Marx and Engels' '' Communist Manifesto'', Lassalle promoted class struggle in a more moderate form. While Marx's theory of the state saw it negatively as an instrument of class rule that should only exist temporarily upon the rise to power of the proletariat and then dismantled, Lassalle accepted the state. Lassalle viewed the state as a means through which workers could enhance their interests and even transform the society to create an economy based on worker-run cooperatives. Lassalle's strategy was primarily electoral and reformist, with Lassalleans contending that the working class needed a political party that fought above all for universal adult male suffrage.

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

and associated the word ''Sozialdemokrat'' with that party. There was a Marxist faction within the ADAV represented by Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist and one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).democratic revolution which in the long run ensured liberty, equality and fraternity, Marxists denounced 1848 as a betrayal of working-class ideals by a bourgeoisie indifferent to the legitimate demands of the proletariat.

Faced with opposition from liberal capitalists to his socialist policies, Lassalle controversially attempted to forge a tactical alliance with the  In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the

In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the  In the aftermath of the Paris Commune's collapse in 1871, Marx praised it in his work ''

In the aftermath of the Paris Commune's collapse in 1871, Marx praised it in his work '' A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British

A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British

The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the

The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the  The term '' revisionist'' was applied to Bernstein by his critics, who referred to themselves as orthodox Marxists, although Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Marx's and Engels' stances, especially in their later years when they advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible. Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder

The term '' revisionist'' was applied to Bernstein by his critics, who referred to themselves as orthodox Marxists, although Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Marx's and Engels' stances, especially in their later years when they advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible. Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder  Bernstein criticized Marxism's concept of "irreconciliable class conflicts" and Marxism's hostility to

Bernstein criticized Marxism's concept of "irreconciliable class conflicts" and Marxism's hostility to  Representing revolutionary socialism, Rosa Luxemburg staunchly condemned Bernstein's revisionism and reformism for being based on "opportunism in social democracy". Luxemburg likened Bernstein's policies to that of the dispute between Marxists and the opportunistic ''Praktiker'' ("pragmatists"). She denounced Bernstein's evolutionary socialism for being a "petty-bourgeois vulgarization of Marxism" and claimed that Bernstein's years of exile in Britain had made him lose familiarity with the situation in Germany, where he was promoting evolutionary socialism. Luxemburg sought to maintain social democracy as a revolutionary Marxist creed. Both Kautsky and Luxemburg condemned Bernstein's philosophy of science as flawed for having abandoned Hegelian dialectics for Kantian philosophical dualism. Russian Marxist George Plekhanov joined Kautsky and Luxemburg in condemning Bernstein for having a neo-Kantian philosophy. Kautsky and Luxemburg contended that Bernstein's empiricist viewpoints depersonalized and dehistoricized the social observer and reducing objects down to facts. Luxemburg associated Bernstein with ethical socialists who she identified as being associated with the bourgeoisie and Kantian liberalism.

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformists and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist measures while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists. Engels' statements in the French newspaper ''Le Figaro'' in which he wrote that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena and argued that this made "us socialists all evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also argued that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power that he predicted could bring "social democracy into power as early as 1898". Engels' stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion. Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism.

Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of ''The Class Struggles in France'' had been edited by Bernstein and Kautsky in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism. While highlighting ''The Communist Manifestos emphasis on winning as a first step the "battle of democracy", Engels also wrote to Kautsky the following on 1 April 1895, four months before his death: "I was amazed to see today in the ''Vorwärts'' an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legality ''quand même''. Which is all the more reason why I should like it to appear in its entirety in the ''Neue Zeit'' in order that this disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who, irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me about it."

After delivering a lecture in Britain to the Fabian Society titled "On What Marx Really Taught" in 1897, Bernstein wrote a letter to the orthodox Marxist August Bebel in which he revealed that he felt conflicted with what he had said at the lecture as well as revealing his intentions regarding revision of Marxism. What Bernstein meant was that he believed that Marx was wrong in assuming that the capitalist economy would collapse as a result of its internal contradictions as by the mid-1890s there was little evidence of such internal contradictions causing this to capitalism. In practice, the SPD "behaved as a Revisionist party and, at the same time, to condemn Revisionism; it continued to preach revolution and to practice reform", notwithstanding its "doctrinal Marxism". The SPD became a party of reform, with social democracy representing "a party that strives after the socialist transformation of society by the means of democratic and economic reforms". This has been described as central to the understanding of 20th-century social democracy.

Representing revolutionary socialism, Rosa Luxemburg staunchly condemned Bernstein's revisionism and reformism for being based on "opportunism in social democracy". Luxemburg likened Bernstein's policies to that of the dispute between Marxists and the opportunistic ''Praktiker'' ("pragmatists"). She denounced Bernstein's evolutionary socialism for being a "petty-bourgeois vulgarization of Marxism" and claimed that Bernstein's years of exile in Britain had made him lose familiarity with the situation in Germany, where he was promoting evolutionary socialism. Luxemburg sought to maintain social democracy as a revolutionary Marxist creed. Both Kautsky and Luxemburg condemned Bernstein's philosophy of science as flawed for having abandoned Hegelian dialectics for Kantian philosophical dualism. Russian Marxist George Plekhanov joined Kautsky and Luxemburg in condemning Bernstein for having a neo-Kantian philosophy. Kautsky and Luxemburg contended that Bernstein's empiricist viewpoints depersonalized and dehistoricized the social observer and reducing objects down to facts. Luxemburg associated Bernstein with ethical socialists who she identified as being associated with the bourgeoisie and Kantian liberalism.

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformists and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist measures while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists. Engels' statements in the French newspaper ''Le Figaro'' in which he wrote that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena and argued that this made "us socialists all evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also argued that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power that he predicted could bring "social democracy into power as early as 1898". Engels' stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion. Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism.

Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of ''The Class Struggles in France'' had been edited by Bernstein and Kautsky in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism. While highlighting ''The Communist Manifestos emphasis on winning as a first step the "battle of democracy", Engels also wrote to Kautsky the following on 1 April 1895, four months before his death: "I was amazed to see today in the ''Vorwärts'' an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legality ''quand même''. Which is all the more reason why I should like it to appear in its entirety in the ''Neue Zeit'' in order that this disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who, irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me about it."

After delivering a lecture in Britain to the Fabian Society titled "On What Marx Really Taught" in 1897, Bernstein wrote a letter to the orthodox Marxist August Bebel in which he revealed that he felt conflicted with what he had said at the lecture as well as revealing his intentions regarding revision of Marxism. What Bernstein meant was that he believed that Marx was wrong in assuming that the capitalist economy would collapse as a result of its internal contradictions as by the mid-1890s there was little evidence of such internal contradictions causing this to capitalism. In practice, the SPD "behaved as a Revisionist party and, at the same time, to condemn Revisionism; it continued to preach revolution and to practice reform", notwithstanding its "doctrinal Marxism". The SPD became a party of reform, with social democracy representing "a party that strives after the socialist transformation of society by the means of democratic and economic reforms". This has been described as central to the understanding of 20th-century social democracy.

The dispute over policies in favour of reform or revolution dominated discussions at the 1899 Hanover Party Conference of the

The dispute over policies in favour of reform or revolution dominated discussions at the 1899 Hanover Party Conference of the  In spite of the two Red Scare periods which substantially hindered the development of the socialist movement, left-wing parties and labour and

In spite of the two Red Scare periods which substantially hindered the development of the socialist movement, left-wing parties and labour and

As tensions between Europe's Great Powers escalated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bernstein feared that Germany's arms race with other powers was increasing the possibility of a major European war. Bernstein's fears were ultimately proven to be prophetic when the outbreak of

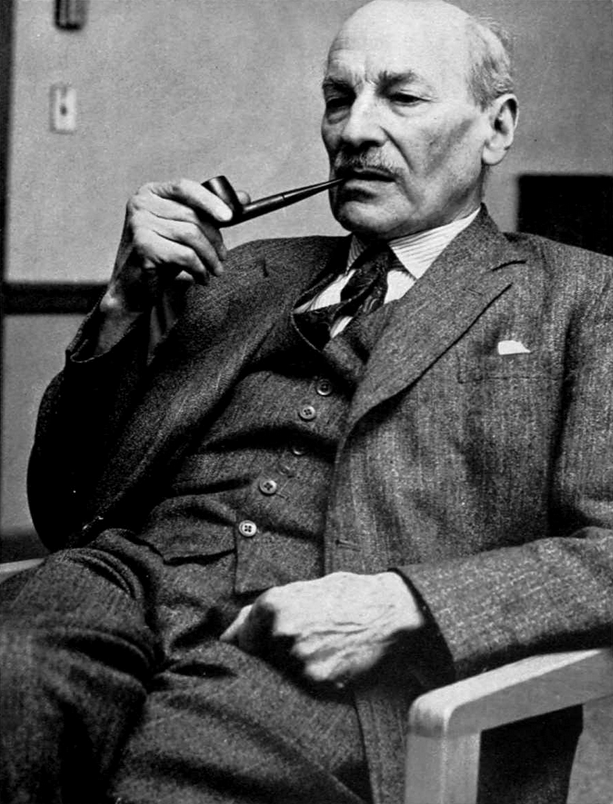

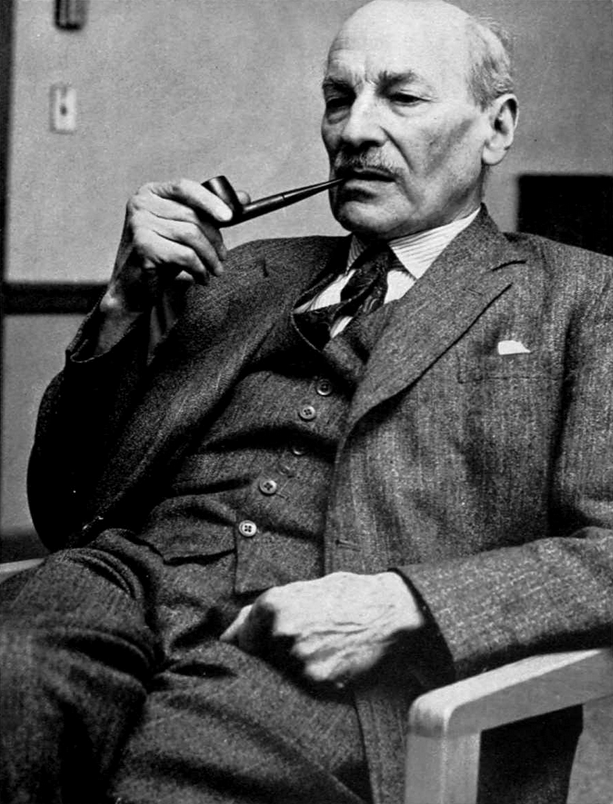

As tensions between Europe's Great Powers escalated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bernstein feared that Germany's arms race with other powers was increasing the possibility of a major European war. Bernstein's fears were ultimately proven to be prophetic when the outbreak of  In Britain, the British Labour Party became divided on the war. Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald was one of a handful of

In Britain, the British Labour Party became divided on the war. Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald was one of a handful of  The overthrow of the tsarist regime in Russia in February 1917 impacted politics in Germany as it ended the legitimation used by Ebert and other pro-war SPD members that Germany was in the war against a reactionary Russian government. With the overthrow of the tsar and revolutionary socialist agitation increased in Russia, such events influenced socialists in Germany. With rising bread shortages in Germany amid war rationing, mass strikes occurred beginning in April 1917 with 300,000 strikers taking part in a strike in Berlin. The strikers demanded bread, freedom, peace and the formation of

The overthrow of the tsarist regime in Russia in February 1917 impacted politics in Germany as it ended the legitimation used by Ebert and other pro-war SPD members that Germany was in the war against a reactionary Russian government. With the overthrow of the tsar and revolutionary socialist agitation increased in Russia, such events influenced socialists in Germany. With rising bread shortages in Germany amid war rationing, mass strikes occurred beginning in April 1917 with 300,000 strikers taking part in a strike in Berlin. The strikers demanded bread, freedom, peace and the formation of  Noske was able to rally groups of mostly reactionary former soldiers, known as the

Noske was able to rally groups of mostly reactionary former soldiers, known as the  After World War I, several attempts were made at a global level to refound the Second International that collapsed amidst national divisions in the war. The Vienna International formed in 1921 attempted to end the rift between reformist socialists, including social democrats; and revolutionary socialists, including communists, particularly the

After World War I, several attempts were made at a global level to refound the Second International that collapsed amidst national divisions in the war. The Vienna International formed in 1921 attempted to end the rift between reformist socialists, including social democrats; and revolutionary socialists, including communists, particularly the  The overall response from the Vienna International was divided. The Mensheviks demanded that the Vienna International immediately condemn Russia's aggression against Georgia, but the majority as represented by German delegate Alfred Henke sought to exercise caution and said that the delegates should wait for confirmation. Russia's invasion of Georgia completely violated the non-aggression treaty signed between Lenin and Zhordania as well as violating Georgia's sovereignty by annexing Georgia directly into the

The overall response from the Vienna International was divided. The Mensheviks demanded that the Vienna International immediately condemn Russia's aggression against Georgia, but the majority as represented by German delegate Alfred Henke sought to exercise caution and said that the delegates should wait for confirmation. Russia's invasion of Georgia completely violated the non-aggression treaty signed between Lenin and Zhordania as well as violating Georgia's sovereignty by annexing Georgia directly into the

The

The  In 1922, Ramsay MacDonald returned to the leadership of the Labour Party after his brief tenure in the Independent Labour Party. In the 1924 general election, the Labour Party won a plurality of seats and was elected as a minority government, but required assistance from the

In 1922, Ramsay MacDonald returned to the leadership of the Labour Party after his brief tenure in the Independent Labour Party. In the 1924 general election, the Labour Party won a plurality of seats and was elected as a minority government, but required assistance from the  In the 1920s, SPD policymaker and Marxist

In the 1920s, SPD policymaker and Marxist  The only social democratic governments in Europe that remained by the early 1930s were in Scandinavia. In the 1930s, several Swedish social democratic leadership figures, including former Swedish prime minister and secretary and chairman of the Socialization Committee

The only social democratic governments in Europe that remained by the early 1930s were in Scandinavia. In the 1930s, several Swedish social democratic leadership figures, including former Swedish prime minister and secretary and chairman of the Socialization Committee  In the Americas, social democracy was rising as a major political force. In Mexico, several social democratic governments and presidents were elected from the 1920s to the 1930s. The most important Mexican social democratic government of this time was that led by president Lázaro Cárdenas and the

In the Americas, social democracy was rising as a major political force. In Mexico, several social democratic governments and presidents were elected from the 1920s to the 1930s. The most important Mexican social democratic government of this time was that led by president Lázaro Cárdenas and the  Similarly, the welfare state in Canada was developed by the Liberal Party of Canada. Nonetheless, the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the precursor to the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), had significant success in provincial Canadian politics. In 1944, the Saskatchewan CCF formed the first socialist government in North America and its leader

Similarly, the welfare state in Canada was developed by the Liberal Party of Canada. Nonetheless, the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the precursor to the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), had significant success in provincial Canadian politics. In 1944, the Saskatchewan CCF formed the first socialist government in North America and its leader  Although well within the liberal and modern liberal American tradition, Franklin D. Roosevelt's more radical, extensive and populist

Although well within the liberal and modern liberal American tradition, Franklin D. Roosevelt's more radical, extensive and populist  While criticized by many leftists and hailed by mainstream observers as having saved American capitalism from a socialist revolution, many communists, socialists and social democrats admired Roosevelt and supported the New Deal, including politicians and activists of European social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party and the French Section of the Workers' International. After initially rejecting the New Deal as part of its

While criticized by many leftists and hailed by mainstream observers as having saved American capitalism from a socialist revolution, many communists, socialists and social democrats admired Roosevelt and supported the New Deal, including politicians and activists of European social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party and the French Section of the Workers' International. After initially rejecting the New Deal as part of its  In Oceania,

In Oceania,

After the

After the  In 1959, the SPD instituted a major policy review with the Godesberg Program. The Godesberg Program eliminated the party's remaining orthodox Marxist policies and the SPD redefined its ideology as ''freiheitlicher Sozialismus'' (

In 1959, the SPD instituted a major policy review with the Godesberg Program. The Godesberg Program eliminated the party's remaining orthodox Marxist policies and the SPD redefined its ideology as ''freiheitlicher Sozialismus'' (

The economic crisis in the Western world in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis during the mid- to late 1970s resulted in the rise of

The economic crisis in the Western world in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis during the mid- to late 1970s resulted in the rise of  The 1989 Socialist International congress was politically significant in that members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the reformist leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev attended the congress. The Socialist International's new Declaration of Principles abandoned previous statements made in the Frankfurt Declaration of 1951 against Soviet-style socialism. After the congress, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's newspaper ''

The 1989 Socialist International congress was politically significant in that members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the reformist leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev attended the congress. The Socialist International's new Declaration of Principles abandoned previous statements made in the Frankfurt Declaration of 1951 against Soviet-style socialism. After the congress, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's newspaper '' In the 1990s, the ideology of the

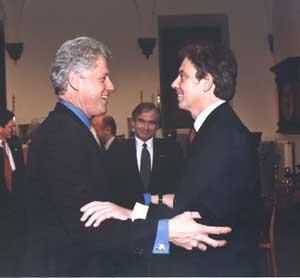

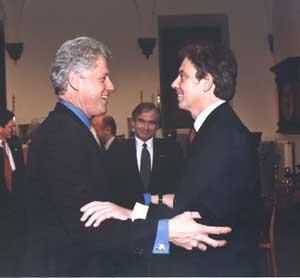

In the 1990s, the ideology of the  When he was a British Labour Party MP, Third Way supporter and former British prime minister

When he was a British Labour Party MP, Third Way supporter and former British prime minister  Giddens dissociated himself from many of the interpretations of the Third Way made in the sphere of day-to-day politics—including

Giddens dissociated himself from many of the interpretations of the Third Way made in the sphere of day-to-day politics—including  Former SPD chairman

Former SPD chairman  Others have claimed that social democracy needs to move past the Third Way, including Olaf Cramme and Patrick Diamond in their book ''After the Third Way: The Future of Social Democracy in Europe'' (2012). Cramme and Diamond recognize that the Third Way arose as an attempt to break down the traditional dichotomy within social democracy between state intervention and markets in the economy, but they contend that the 2007–2012 global economic crisis requires that social democracy must rethink its

Others have claimed that social democracy needs to move past the Third Way, including Olaf Cramme and Patrick Diamond in their book ''After the Third Way: The Future of Social Democracy in Europe'' (2012). Cramme and Diamond recognize that the Third Way arose as an attempt to break down the traditional dichotomy within social democracy between state intervention and markets in the economy, but they contend that the 2007–2012 global economic crisis requires that social democracy must rethink its

Beginning in the 2000s, with the global economic crisis in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the social democratic parties that had dominated some of the post-World War II political landscape in Western Europe were under pressure in some countries to the extent that a commentator in '' Foreign Affairs'' called it an "implosion of the centre-left". The

Beginning in the 2000s, with the global economic crisis in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the social democratic parties that had dominated some of the post-World War II political landscape in Western Europe were under pressure in some countries to the extent that a commentator in '' Foreign Affairs'' called it an "implosion of the centre-left". The  In 2017, support for social democratic parties in other countries such as Denmark and Portugal was relatively strong in polls. Moreover, the decline of the social democratic parties in some countries was accompanied by a surge in the support for other centre-left or left-wing parties such as Syriza in Greece, the Left-Green Movement in Iceland and Podemos (Spanish political party), Podemos in Spain. Several explanations for the European decline have been proposed. Some commentators highlight that the social democratic support of national fragmentation and labour market deregulation had become less popular among potential voters. Others such as the French political scientist Pierre Manent emphasize the need for social democrats to rehabilitate and reinvigorate the idea of nationhood.

In a 2017 article in ''The Political Quarterly'', Jörg Michael Dostal explains the decline in Germany with electoral disillusionment with

In 2017, support for social democratic parties in other countries such as Denmark and Portugal was relatively strong in polls. Moreover, the decline of the social democratic parties in some countries was accompanied by a surge in the support for other centre-left or left-wing parties such as Syriza in Greece, the Left-Green Movement in Iceland and Podemos (Spanish political party), Podemos in Spain. Several explanations for the European decline have been proposed. Some commentators highlight that the social democratic support of national fragmentation and labour market deregulation had become less popular among potential voters. Others such as the French political scientist Pierre Manent emphasize the need for social democrats to rehabilitate and reinvigorate the idea of nationhood.

In a 2017 article in ''The Political Quarterly'', Jörg Michael Dostal explains the decline in Germany with electoral disillusionment with  Several social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn have outright rejected the Third Way strategy and moved back to the left on economics and class issues. After running in the 2014 PSOE primary election as a centrist profile, Pedro Sánchez later switched to the left in his successful 2017 bid to return to the PSOE leadership in which he stood for a refoundation of social democracy in order to transition to a post-capitalist society, putting an end to neoliberal capitalism. A key personal idea posed in Sánchez's 2019 ''Manual de Resistencia'' book is the indissoluble link between social democracy and Europe.

Other parties such as the Danish Social Democrats (Denmark), Social Democrats also became increasingly skeptical of neoliberal mass immigration from a left-wing point of view. The party believes it has had negative impacts for much of the population and it has been seen as a more pressing issue since at least 2001 after the 11 September attacks that has intensified during the 2015 European migrant crisis. The perception of the party being neoliberal and soft on immigration during the era of neoliberal globalization contributed to its poor electoral performance in the early 21st century. In a recent biography, the Danish Social Democrats party leader and prime minister Mette Frederiksen argued: "For me, it is becoming increasingly clear that the price of unregulated globalisation, mass immigration and the free movement of labour is paid for by the lower classes". Frederiksen later shifted her stance on immigration by allowing more foreign labour and reversing plans to hold foreign criminals offshore after winning government. A 2020 study disputed the notion that anti-immigration positions would help social democratic parties. The study found that "more authoritarian/nationalist and more anti-EU positions are if anything associated with lower rather than greater electoral support for social democratic parties".

Several social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn have outright rejected the Third Way strategy and moved back to the left on economics and class issues. After running in the 2014 PSOE primary election as a centrist profile, Pedro Sánchez later switched to the left in his successful 2017 bid to return to the PSOE leadership in which he stood for a refoundation of social democracy in order to transition to a post-capitalist society, putting an end to neoliberal capitalism. A key personal idea posed in Sánchez's 2019 ''Manual de Resistencia'' book is the indissoluble link between social democracy and Europe.

Other parties such as the Danish Social Democrats (Denmark), Social Democrats also became increasingly skeptical of neoliberal mass immigration from a left-wing point of view. The party believes it has had negative impacts for much of the population and it has been seen as a more pressing issue since at least 2001 after the 11 September attacks that has intensified during the 2015 European migrant crisis. The perception of the party being neoliberal and soft on immigration during the era of neoliberal globalization contributed to its poor electoral performance in the early 21st century. In a recent biography, the Danish Social Democrats party leader and prime minister Mette Frederiksen argued: "For me, it is becoming increasingly clear that the price of unregulated globalisation, mass immigration and the free movement of labour is paid for by the lower classes". Frederiksen later shifted her stance on immigration by allowing more foreign labour and reversing plans to hold foreign criminals offshore after winning government. A 2020 study disputed the notion that anti-immigration positions would help social democratic parties. The study found that "more authoritarian/nationalist and more anti-EU positions are if anything associated with lower rather than greater electoral support for social democratic parties".

In 2016, Senator from Vermont Bernie Sanders, who describes himself as a ''democratic socialist'', made a bid for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party 2016 Democratic Party presidential candidates, presidential candidate, gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation, working-class Americans, and rural voters, but ultimately the presidential nomination was won by a centrist candidate Hillary Clinton in June 2016 and Sanders withdrew the race by July 2016 but Sanders still influenced the party platform. Sanders ran again in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries, briefly becoming the front-runner in February until Super Tuesday 2020, Super Tuesday in March and suspending his campaign in April. Nonetheless, Sanders would remain on the ballot in states that had not yet voted to influence the Democratic Party's platform as he did in 2016.

Since his praise of the Nordic model indicated focus on social democracy as opposed to views involving

In 2016, Senator from Vermont Bernie Sanders, who describes himself as a ''democratic socialist'', made a bid for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party 2016 Democratic Party presidential candidates, presidential candidate, gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation, working-class Americans, and rural voters, but ultimately the presidential nomination was won by a centrist candidate Hillary Clinton in June 2016 and Sanders withdrew the race by July 2016 but Sanders still influenced the party platform. Sanders ran again in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries, briefly becoming the front-runner in February until Super Tuesday 2020, Super Tuesday in March and suspending his campaign in April. Nonetheless, Sanders would remain on the ballot in states that had not yet voted to influence the Democratic Party's platform as he did in 2016.

Since his praise of the Nordic model indicated focus on social democracy as opposed to views involving

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

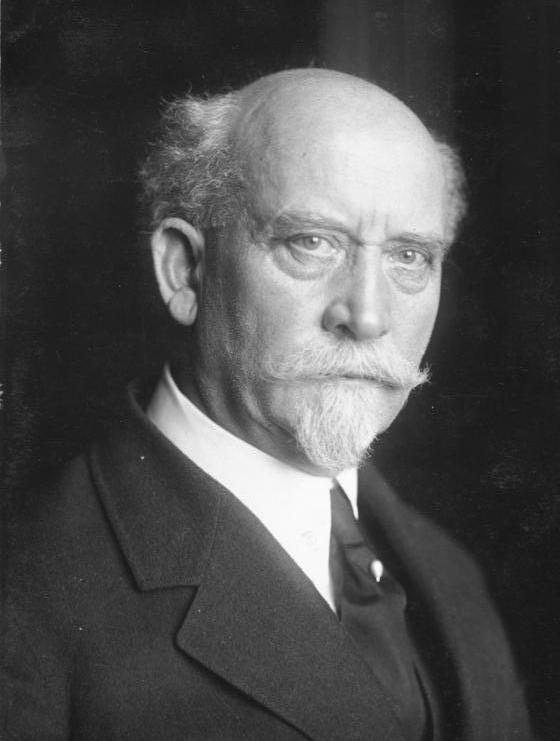

Junkers due to their communitarian anti-bourgeois attitudes as well as with Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Friction in the ADAV arose over Lassalle's policy of a friendly approach to Bismarck that had incorrectly presumed that Bismarck would in turn be friendly towards them. This approach was opposed by the party's faction associated with Marx and Engels, including Liebknecht. Opposition in the ADAV to Lassalle's friendly approach to Bismarck's government resulted in Liebknecht resigning from his position as editor of ''Sozialdemokrat'' and leaving the ADAV in 1865. In 1869, August Bebel and Liebknecht founded the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SDAP) was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Founded in Eisenach in 1869, the SDAP e ...

(SDAP) as a merger of the petty-bourgeois

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, literally 'small bourgeoisie'; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a French term that refers to a social class composed of semi-autonomous peasants and small-scale merchants whose politico-economic ideological sta ...

Saxon People's Party

The Saxon People's Party (german: Sächsische Volkspartei) was a left-liberal and radical democratic party with socialist leanings in Germany, founded by Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel on 19 August 1866 in Chemnitz, and integrated into the n ...

(SVP), a faction of the ADAV and members of the League of German Workers' Associations (VDA).

Although the SDAP was not officially Marxist, it was the first major working-class organization to be led by Marxists and both Marx and Engels had direct association with the party. The party adopted stances similar to those adopted by Marx at the First International. There was intense rivalry and antagonism between the SDAP and the ADAV, with the SDAP being highly hostile to the Prussian government while the ADAV pursued a reformist and more cooperative approach. This rivalry reached its height involving the two parties' stances on the Franco-Prussian War, with the SDAP refusing to support Prussia's war effort by claiming it was an imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

war pursued by Bismarck while the ADAV supported the war as a defensive one because it saw Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

and France as an "overreacting aggressor".

In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the

In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

. The Paris Commune appealed both to the citizens of Paris regardless of class as well as to the working class, a major base of support for the government, via militant rhetoric. In spite of such militant rhetoric to appeal to the working class, the Paris Commune received substantial support from the middle-class bourgeoisie of Paris, including shopkeepers and merchants. In part due to its sizeable number neo- Proudhonians and neo-Jacobins in the Central Committee, the Paris Commune declared that it was not opposed to private property, but that it rather hoped to create the widest distribution of it. The political composition of the Paris Commune included twenty-five neo-Jacobins, fifteen to twenty neo-Proudhonians and proto-syndicalists

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

, nine or ten Blanquists, a variety of radical republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

and a few members of the First International influenced by Marx.

In the aftermath of the Paris Commune's collapse in 1871, Marx praised it in his work ''

In the aftermath of the Paris Commune's collapse in 1871, Marx praised it in his work ''The Civil War in France

"The Civil War in France" (German: "Der Bürgerkrieg in Frankreich") was a pamphlet written by Karl Marx, as an official statement of the General Council of the International on the character and significance of the struggle of the Communards in t ...

'' (1871) for its achievements in spite of its pro-bourgeois influences and called it an excellent model of the dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

in practice as it had dismantled the apparatus of the bourgeois state, including its huge bureaucracy, military and executive, judicial and legislative institutions, replacing it with a working-class state with broad popular support. The Paris Commune's collapse and the persecution of its anarchist supporters had the effect of weakening the influence of the Bakuninist anarchists in the First International which resulted in Marx expelling the weakened rival Bakuninists from the International a year later. In Britain, the achievement of the legalization of trade unions under the Trade Union Act 1871

The Trade Union Act 1871 (34 & 35 Vicc 31 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which legalised trade unions for the first time in the United Kingdom. This was one of the founding pieces of legislation in UK labour law, though it has ...

drew British trade unionists to believe that working conditions could be improved through parliamentary means.

At the Hague Congress of 1872, Marx made a remark in which he admitted that while there are countries "where the workers can attain their goal by peaceful means", in most European countries "the lever of our revolution must be force". In 1875, Marx attacked the Gotha Program that became the program of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP) in the same year in his ''Critique of the Gotha Program

The ''Critique of the Gotha Programme'' (german: Kritik des Gothaer Programms) is a document based on a letter by Karl Marx written in early May 1875 to the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), with whom Marx and Friedrich Engels wer ...

''. Marx was not optimistic that Germany at the time was open to a peaceful means to achieve socialism, especially after German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had enacted the Anti-Socialist Laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

in 1878. At the time of the Anti-Socialist Laws beginning to be drafted but not yet published in 1878, Marx spoke of the possibilities of legislative reforms by an elected government composed of working-class legislative members, but also of the willingness to use force should force be used against the working class.

In his study ''England in 1845 and in 1885'', Engels wrote a study that analysed the changes in the British class system from 1845 to 1885 in which he commended the Chartist movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

for being responsible for the achievement of major breakthroughs for the working class. Engels stated that during this time Britain's industrial bourgeoisie had learned that "the middle class can never obtain full social and political power over the nation except by the help of the working class". In addition, he noticed a "gradual change over the relations between the two classes". This change he described was manifested in the change of laws in Britain that granted political changes in favour of the working class that the Chartist movement had demanded for years, arguing that they made a "near approach to 'universal suffrage', at least such as it now exists in Germany".

A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British

A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

. Founded in 1884 by Frank Podmore

Frank Podmore (5 February 1856 – 14 August 1910) was an English author, and founding member of the Fabian Society. He is best known as an influential member of the Society for Psychical Research and for his sceptical writings on spiritualism.

...

, it emphasized the need for a gradualist evolutionary and reformist approach to the achievement of socialism. The Fabian Society was founded as a splinter group from the Fellowship of the New Life

The Fellowship of the New Life was a British organisation in the 19th century, most famous for a splinter group, the Fabian Society.

It was founded in 1883, by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included the poet Edwa ...

due to opposition within that group to socialism. Unlike Marxism, Fabianism did not promote itself as a working-class movement and it largely had middle-class members. The Fabian Society published the ''Fabian Essays on Socialism'' (1889), substantially written by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

. Shaw referred to Fabians as "all Social Democrats, with a common of the necessity of vesting the organization of industry and the material of production in a State identified with the whole people by complete Democracy". Other important early Fabians included Sidney Webb, who from 1887 to 1891 wrote the bulk of the Fabian Society's official policies. Fabianism would become a major influence on the British labour movement.

Late 19th century to early 20th century

Second International era and reform or revolution dispute (1889–1914)

The social democratic movement came into being through a division within the socialist movement. Starting in the 1880s and culminating in the 1910s and 1920s, there was a division within the socialist movement between those who insisted upon political revolution as a precondition for the achievement of socialist goals and those who maintained that a gradual or evolutionary path to socialism was both possible and desirable. German social democracy as exemplified by the SPD was the model for the world social democratic movement. The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the

The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP) founded in 1893. Important ILP members were affiliated with the Fabian Society, including Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

and Ramsay MacDonald—the future British Prime Minister. Fabian influence in British government affairs also emerged such as Fabian member Sidney Webb being chosen to take part in writing what became the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on Labour. While he was nominally a member of the Fabian Society, Hardie had close relations with certain Fabians such as Shaw while he was antagonistic to others such as the Webbs. As ILP leader, Hardie rejected revolutionary politics while declaring that he believed the party's tactics should be "as constitutional as the Fabians".

Another important Fabian figure who joined the ILP was Robert Blatchford

Robert Peel Glanville Blatchford (17 March 1851 – 17 December 1943) was an English socialist campaigner, journalist, and author in the United Kingdom. He was also noted as a prominent atheist, nationalist and opponent of eugenics. In the early ...

who wrote the work '' Merrie England'' (1894) that endorsed municipal socialism

Municipal socialism is a type of socialism that uses local government to further socialist aims. It is a form of municipalism in which its explicitly socialist aims are clearly stated. In some contexts the word "municipalism" was tainted with th ...

. ''Merrie England'' was a major publication that sold 750,000 copies within one year. In ''Merrie England'', Blatchford distinguished two types of socialism, namely an ideal socialism and a practical socialism. Blatchford's practical socialism was a state socialism that identified existing state enterprise such as the Post Office run by the municipalities as a demonstration of practical socialism in action while claiming that practical socialism should involve the extension of state enterprise to the means of production as common property of the people. Although endorsing state socialism

State socialism is a political and economic ideology within the socialist movement that advocates state ownership of the means of production. This is intended either as a temporary measure, or as a characteristic of socialism in the transition ...

, Blatchford's ''Merrie England'' and his other writings were nonetheless influenced by anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

—as Blatchford himself attested to—and Morris' anarcho-communist themes are present in ''Merrie England''. Shaw published the ''Report on Fabian Policy'' (1896) that declared: "The Fabian Society does not suggest that the State should monopolize industry as against private enterprise or individual initiative".

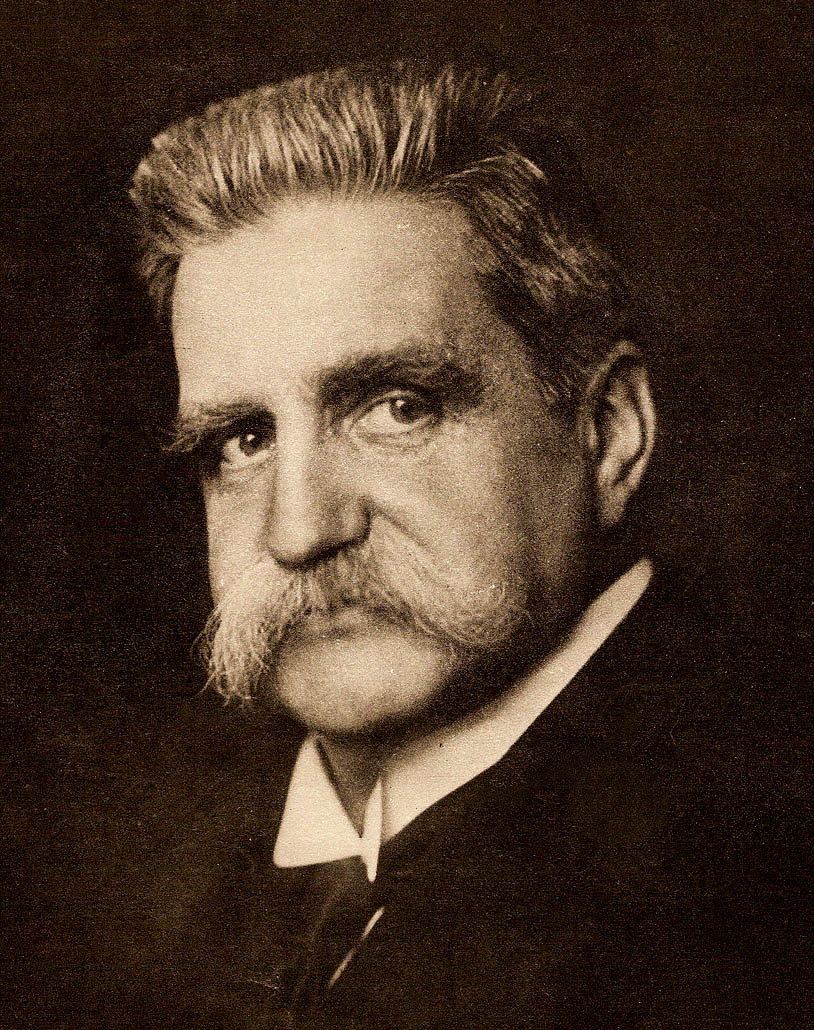

Major developments in social democracy as a whole emerged with the ascendance of Eduard Bernstein as a proponent of reformist socialism

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

and an adherent of Marxism. Bernstein had resided in Britain in the 1880s at the time when Fabianism was arising and is believed to have been strongly influenced by Fabianism. However, he publicly denied having strong Fabian influences on his thought. Bernstein did acknowledge that he was influenced by Kantian

Kantianism is the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). The term ''Kantianism'' or ''Kantian'' is sometimes also used to describe contemporary positions in philosophy of mind, ...

epistemological scepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the p ...

while he rejected Hegelianism. He and his supporters urged the SPD to merge Kantian ethics

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory developed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that: "It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be conside ...

with Marxian political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

. On the role of Kantian criticism within socialism which "can serve as a pointer to the satisfying solution to our problem", Bernstein argued that " r critique must be direct against both a scepticism that undermines all theoretical thought, and a dogmatism that relies on ready-made formulas". An evolutionist rather than a revolutionist, his policy of gradualism rejected the radical overthrow of capitalism and advocated legal reforms through legislative democratic channels to achieve socialist objectives—i.e. social democracy must cooperatively work within existing capitalist societies to promote and foster the creation of socialist society. As capitalism grew stronger, Bernstein rejected the view of some orthodox Marxists that socialism would come after a catastrophic crisis of capitalism. He came to believe that rather than socialism developing with a social revolution, capitalism would eventually evolve into socialism through social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

s. Bernstein commended Marx's and Engels' later works which advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible.

The term '' revisionist'' was applied to Bernstein by his critics, who referred to themselves as orthodox Marxists, although Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Marx's and Engels' stances, especially in their later years when they advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible. Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder

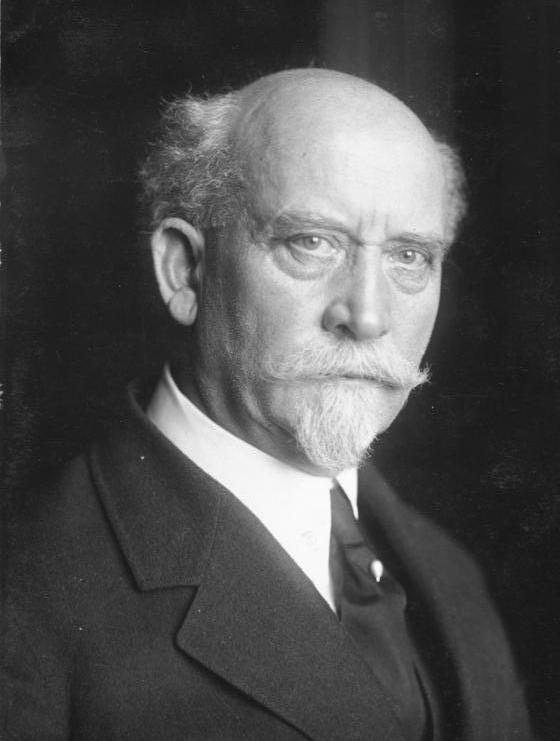

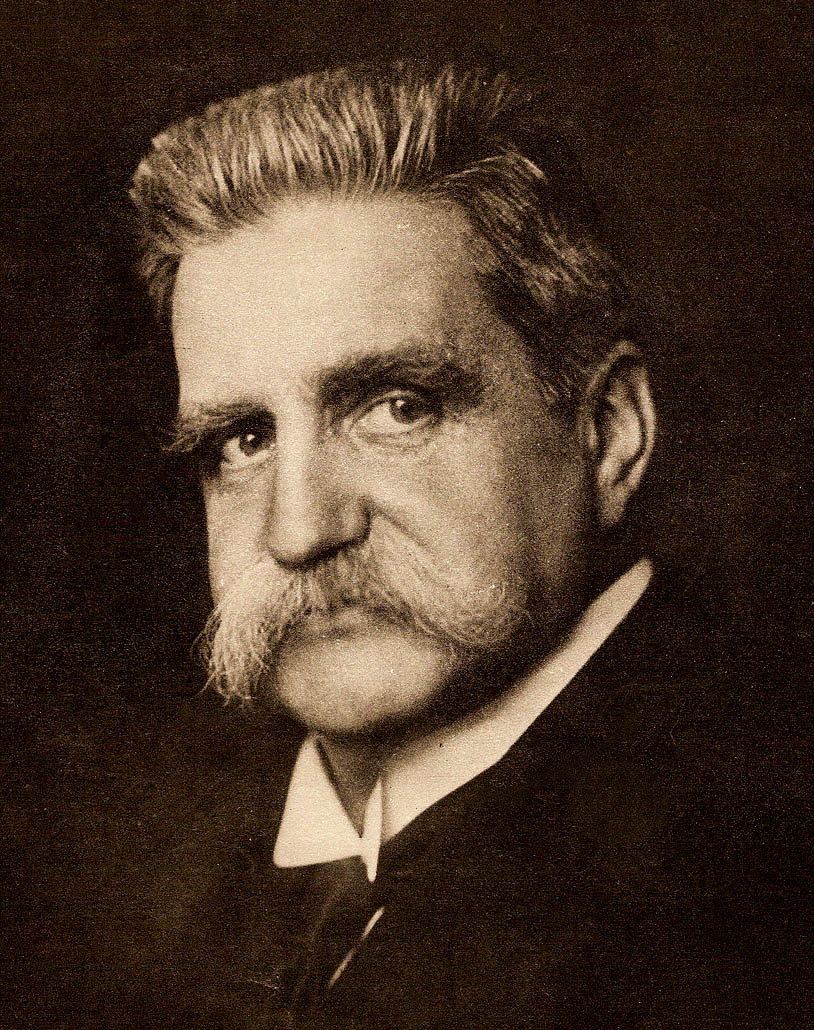

The term '' revisionist'' was applied to Bernstein by his critics, who referred to themselves as orthodox Marxists, although Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Marx's and Engels' stances, especially in their later years when they advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible. Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels i ...

for having disregarded Marx's view of the necessity of evolution of capitalism to achieve socialism by replacing it with an either/or polarization between capitalism and socialism, claiming that Kautsky disregarded Marx's emphasis on the role of parliamentary democracy in achieving socialism as well as criticizing Kautsky for his idealization of state socialism. Despite Bernstein and his revisionist faction's accusations, Kautsky did not deny a role for democracy in the achievement of socialism as he argued that Marx's dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

was not a form of government that rejected democracy as critics had claimed it was, but rather it was a state of affairs that Marx expected would arise should the proletariat gain power and be faced with fighting a violent reactionary opposition.

Bernstein had held close association to Marx and Engels, but he saw flaws in Marxian thinking and began such criticism when he investigated and challenged the Marxian materialist theory of history. He rejected significant parts of Marxian theory that were based upon Hegelian

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

and also rejected the Hegelian dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to ...

al perspective. Bernstein distinguished between early Marxism as being its immature form as exemplified by ''The Communist Manifesto'', written by Marx and Engels in their youth, that he opposed for what he regarded as its violent Blanquist