History of science and technology in Mexico on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of science and technology in Mexico spans many years.

The

The

After the

After the

During the 20th century, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. New universities and research institutes were established. The

During the 20th century, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. New universities and research institutes were established. The  In the 1930s

In the 1930s  In 1959, the

In 1959, the

There is, as yet, little evidence that Mexico's economy will undergo deep structural changes overnight. The absence of any industrial policy suggests that the Mexican economy will remain dependent on oil and manufactured exports associated with global value chains, as well as remittances. Mexico's main targets, as outlined in the National Development Plan for 2019–2024, relate to national challenges such as poverty, inequality, employment and education. Mexico submitted a Voluntary National Review for the Highlevel Political Forum on Sustainable Development in 2018 and the current government has linked the National Development Plan to The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The government is working to connect science better with local challenges. Its new initiative, entitled Strategic National Programmes (PRONACES), allocates funding to research projects with a focus on societal issues at local level.

Programmes include: contaminating processes and the socioenvironmental impact of toxins; the promotion of literacy as a strategy for social inclusion; and the sustainability of socioecological systems.

PRONACES is co-ordinated by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). In 2019, PRONACES accounted for just 1.1% of CONACYT's budget but recent changes suggest that resources may be reassigned to this new programme. Since 2019, the government has reverted to a linear view of innovation that minimizes the vital role played by the business sector in innovation. One consequence of this policy shift has been that CONACYT no longer funds private business ventures, although it does still engage in other forms of public–private partnership like with the Querétaro Aerospace Cluster.

There is, as yet, little evidence that Mexico's economy will undergo deep structural changes overnight. The absence of any industrial policy suggests that the Mexican economy will remain dependent on oil and manufactured exports associated with global value chains, as well as remittances. Mexico's main targets, as outlined in the National Development Plan for 2019–2024, relate to national challenges such as poverty, inequality, employment and education. Mexico submitted a Voluntary National Review for the Highlevel Political Forum on Sustainable Development in 2018 and the current government has linked the National Development Plan to The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The government is working to connect science better with local challenges. Its new initiative, entitled Strategic National Programmes (PRONACES), allocates funding to research projects with a focus on societal issues at local level.

Programmes include: contaminating processes and the socioenvironmental impact of toxins; the promotion of literacy as a strategy for social inclusion; and the sustainability of socioecological systems.

PRONACES is co-ordinated by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). In 2019, PRONACES accounted for just 1.1% of CONACYT's budget but recent changes suggest that resources may be reassigned to this new programme. Since 2019, the government has reverted to a linear view of innovation that minimizes the vital role played by the business sector in innovation. One consequence of this policy shift has been that CONACYT no longer funds private business ventures, although it does still engage in other forms of public–private partnership like with the Querétaro Aerospace Cluster.

Since 2019, the government has been gradually winding down the sectoral funds programme, as part of the curb on allocating resources to promote business innovation. In 2019 and 2020, CONACYT did not issue any calls for project proposals, meaning that only those projects having received funding in previous years remain operational.

The Law on Science and Technology (2002) stipulates that CONACYT is entitled to sign agreements with various ministries and other government bodies to cofinance each sectoral fund. Technical committees were set up to assign public resources to priority economic sectors. By 2005, there were 17 of these mission-oriented funds in sectors that included agriculture, energy, environment and health.

The amount of resources allocated to the sectoral funds has always been modest; by 2019, these amounted to 2.1% of CONACYT's budget.

In 2020, the government decided to eliminate sectoral funds altogether without undertaking any robust evaluation to justify their disappearance.

Since 2019, the government has been gradually winding down the sectoral funds programme, as part of the curb on allocating resources to promote business innovation. In 2019 and 2020, CONACYT did not issue any calls for project proposals, meaning that only those projects having received funding in previous years remain operational.

The Law on Science and Technology (2002) stipulates that CONACYT is entitled to sign agreements with various ministries and other government bodies to cofinance each sectoral fund. Technical committees were set up to assign public resources to priority economic sectors. By 2005, there were 17 of these mission-oriented funds in sectors that included agriculture, energy, environment and health.

The amount of resources allocated to the sectoral funds has always been modest; by 2019, these amounted to 2.1% of CONACYT's budget.

In 2020, the government decided to eliminate sectoral funds altogether without undertaking any robust evaluation to justify their disappearance.

''Tecnología y Diseño''

*2018: (Tie)

**Ricardo Chicurel Uziel

**Leticia Myriam Torres Guerra

*2017:Emilio Sacristan Rock

*2016: (Tie)

**Lourival Possani Postay

**Luis Enrique Sucar Succar

*2015:

**Raúl Rojas

**Enrique Galindo Fentanes

*2014: José Mauricio López Romero

*2013: Martín Ramón Aluja Schuneman Hofer

*2012: Sergio Antonio Estrada Parra

*2011: Raúl Gerardo Quintero Flores

*2010: Sergio Revah Moiseev

*2009: (Tie)

**Blanca Elena Jiménez Cisneros

**José Luis Leyva Montiel

*2008: María de los Ángeles Valdés

*2007: Miguel Pedro Romo Organista

*2006: Fernando Samaniego Verduzco

*2005: Alejandro Alagón Cano

*2004: (Tie)

**Héctor Mario Gómez Galvarriata

**Martín Guillermo Hernández Luna

**Arturo Menchaca

*2003: Octavio Manero Brito

*2002: Alexander Balankin

*2001: Filberto Vázquez Dávila

*2000: Francisco Alfonso Larque Saavedra

*1999: Jesús Gonzales Hernández

*1997: (Tie)

** Baltasar Mena Iniesta

** Feliciano Sánchez Silencio

*1996: (Tie)

** Adolfo Guzmán Arenas

** María Luisa Ortega Delgado

*1995: Alfredo Sánchez Marroquín

*1994: (Tie)

** Francisco Sánchez Sesma

** Juan Vázquez Lomberta

*1993: José Ricardo Gómez Romero

*1992: (Tie)

** Lorenzo Martínez Gómez

** Gabriel Torres Villaseñor

*1991: (Tie)

** Octavio Paredes López

** Roberto Meli Piralla

*1990: (Tie)

** Daniel Reséndiz Núñez

** Juan Milton Garduño

*1988: Mayra de la Torre

*1987: Enrique Hong Chong

*1986: Daniel Malacara Hernández

*1985: José Luis Sánchez Bribiesca

*1984: Jorge Suárez Díaz

*1983: José Antonio Ruiz de la Herrán Villagómez

*1982: Raúl J. Marsal Córdoba

*1981: Luis Esteva Maraboto

*1980: Marcos Mazari Menzer

*1979: Juan Celada Salmón

*1978: Enrique del Moral

*1977: Francisco Rafael del Valle Canseco

*1976: (Tie)

** Reinaldo Pérez Rayón

** Wenceslao X. López Martín del Campo

''Tecnología y Diseño''

*2018: (Tie)

**Ricardo Chicurel Uziel

**Leticia Myriam Torres Guerra

*2017:Emilio Sacristan Rock

*2016: (Tie)

**Lourival Possani Postay

**Luis Enrique Sucar Succar

*2015:

**Raúl Rojas

**Enrique Galindo Fentanes

*2014: José Mauricio López Romero

*2013: Martín Ramón Aluja Schuneman Hofer

*2012: Sergio Antonio Estrada Parra

*2011: Raúl Gerardo Quintero Flores

*2010: Sergio Revah Moiseev

*2009: (Tie)

**Blanca Elena Jiménez Cisneros

**José Luis Leyva Montiel

*2008: María de los Ángeles Valdés

*2007: Miguel Pedro Romo Organista

*2006: Fernando Samaniego Verduzco

*2005: Alejandro Alagón Cano

*2004: (Tie)

**Héctor Mario Gómez Galvarriata

**Martín Guillermo Hernández Luna

**Arturo Menchaca

*2003: Octavio Manero Brito

*2002: Alexander Balankin

*2001: Filberto Vázquez Dávila

*2000: Francisco Alfonso Larque Saavedra

*1999: Jesús Gonzales Hernández

*1997: (Tie)

** Baltasar Mena Iniesta

** Feliciano Sánchez Silencio

*1996: (Tie)

** Adolfo Guzmán Arenas

** María Luisa Ortega Delgado

*1995: Alfredo Sánchez Marroquín

*1994: (Tie)

** Francisco Sánchez Sesma

** Juan Vázquez Lomberta

*1993: José Ricardo Gómez Romero

*1992: (Tie)

** Lorenzo Martínez Gómez

** Gabriel Torres Villaseñor

*1991: (Tie)

** Octavio Paredes López

** Roberto Meli Piralla

*1990: (Tie)

** Daniel Reséndiz Núñez

** Juan Milton Garduño

*1988: Mayra de la Torre

*1987: Enrique Hong Chong

*1986: Daniel Malacara Hernández

*1985: José Luis Sánchez Bribiesca

*1984: Jorge Suárez Díaz

*1983: José Antonio Ruiz de la Herrán Villagómez

*1982: Raúl J. Marsal Córdoba

*1981: Luis Esteva Maraboto

*1980: Marcos Mazari Menzer

*1979: Juan Celada Salmón

*1978: Enrique del Moral

*1977: Francisco Rafael del Valle Canseco

*1976: (Tie)

** Reinaldo Pérez Rayón

** Wenceslao X. López Martín del Campo

Héctor García-Molina a Mexican-American computer scientist and Professor in the Departments of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at Stanford University was advisor to Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google, from 1993 to 1997 when he was a computer science student at Stanford. In March 2015, Mexican-born engineer Luis Velasco, who works at NASA, designs and engineers robots for the company. He obtained a scholarship at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah and studied mechanical engineering. Details of a mousepad designed by Armando M. Fernandez were published in the Xerox Disclosure Journal in 1979.

In February 2015, SpaceX began developing a Space suit#SpaceX suit ("Starman suit"), space suit for astronauts to wear within the SpaceX Dragon 2, Dragon 2 space capsule.

Its appearance was jointly designed by Jose Fernandez—a Mexican Hollywood costume designer known for his works for superhero film, superhero and science fiction films—and SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk. According to SpaceX, the spacesuit has key features such as a 3D printed Space suit helmet, touchscreen-compatible gloves, flame resistant outer layer, and hearing protection during ascent and reentry. Furthermore, each suit “can provide a pressurized environment for all crew members aboard Dragon in atypical situations. This suit also routes communications and cooling systems to the astronauts aboard Dragon during regular flight.”

The Space For Humanity initiative selected Katya Echazarreta out of over 7,000 applicants to fly to space with Blue Origin NS-21 as a Space for Humanity Ambassador. Launched on June 4, 2022, she became the first Mexican-born woman in space.

* Alvarez - Gonzalez Rafael - (molecular biologist)

* Albert Baez, Albert Vinicio Bae - (

Héctor García-Molina a Mexican-American computer scientist and Professor in the Departments of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at Stanford University was advisor to Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google, from 1993 to 1997 when he was a computer science student at Stanford. In March 2015, Mexican-born engineer Luis Velasco, who works at NASA, designs and engineers robots for the company. He obtained a scholarship at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah and studied mechanical engineering. Details of a mousepad designed by Armando M. Fernandez were published in the Xerox Disclosure Journal in 1979.

In February 2015, SpaceX began developing a Space suit#SpaceX suit ("Starman suit"), space suit for astronauts to wear within the SpaceX Dragon 2, Dragon 2 space capsule.

Its appearance was jointly designed by Jose Fernandez—a Mexican Hollywood costume designer known for his works for superhero film, superhero and science fiction films—and SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk. According to SpaceX, the spacesuit has key features such as a 3D printed Space suit helmet, touchscreen-compatible gloves, flame resistant outer layer, and hearing protection during ascent and reentry. Furthermore, each suit “can provide a pressurized environment for all crew members aboard Dragon in atypical situations. This suit also routes communications and cooling systems to the astronauts aboard Dragon during regular flight.”

The Space For Humanity initiative selected Katya Echazarreta out of over 7,000 applicants to fly to space with Blue Origin NS-21 as a Space for Humanity Ambassador. Launched on June 4, 2022, she became the first Mexican-born woman in space.

* Alvarez - Gonzalez Rafael - (molecular biologist)

* Albert Baez, Albert Vinicio Bae - (

SCImago: Scientometrics Research Group

*https://www.conacyt.gob.mx/ *http://cienciamx.com/index.php * Newton en la ciencia novohispana https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/a05c53_332cf2552e0940a088279d77de1b81db.pdf {{DEFAULTSORT:Science And Technology In Mexico Science and technology in Mexico,

Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

Mesoamerican

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Withi ...

civilizations developed mathematics, astronomy, and calendrics, and solved technological problems of water management for agriculture and flood control in Central Mexico.

Following the Spanish conquest in 1521, New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

(colonial Mexico) was brought into the European sphere of science and technology. The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico

The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (in es, Real y Pontificia Universidad de México) was founded on 21 September 1551 by Royal Decree signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles I of Spain, in Valladolid, Spain. It is generally co ...

, established in 1551, was a hub of intellectual and religious development in colonial Mexico for over a century. During the Spanish American Enlightenment

The ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment, which emphasized reason, science, practicality, clarity rather than obscurantism, and secularism, were transmitted from France to the New World in the eighteenth century, following the establishment of th ...

in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, the colony made considerable progress in science, but following the war of independence and political instability in the early nineteenth century, progress stalled.

During the late 19th century under the regime of Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

, the process of industrialization began in Mexico. Following the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, a ten-year civil war, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. During the 20th century, new universities, such as the National Polytechnical Institute, Monterrey Institute of Technology

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM) ( en, Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education), also known as Tecnológico de Monterrey or just Tec, is a secular and Mixed-sex education, coeducational private ...

and research institutes, such as those at the National Autonomous University of Mexico

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ( es, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It is consistently ranked as one of the best universities in Latin America, where it's also the bigges ...

, were established in Mexico.

According to the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

, Mexico is Latin America's largest exporter of high-technology goods (High-technology exports are manufactured goods that involve high R&D intensity, such as in aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments, and electrical machinery) with $40.7 billion worth of high-technology goods exports in 2012. Mexican high-technology exports accounted for 17% of all manufactured goods in the country in 2012 according to the World Bank.

Indigenous Civilizations

The

The Olmec

The Olmecs () were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that t ...

, a Pre-Columbian civilization living in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, calendar system required an advanced understanding of mathematics. The Olmec number system was based on 20 instead of decimal and used three symbols- a dot for one, a bar for five, and a shell-like symbol for zero. The concept of zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. In place-value notation

Positional notation (or place-value notation, or positional numeral system) usually denotes the extension to any base of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system (or ...

is one of the Olmecs' greatest achievements. It permitted numbers to be written by position and allowed for complex calculations. Although the invention of zero is often attributed to the Mayans

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical reg ...

, it was originally conceived by the Olmecs.

To predict planting and harvesting times, early peoples studied the movements of the sun, stars, and planets. They used this information to make calendars. The Aztecs

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

created two calendars- one for farming, and one for religion. The farming calendar let them know when to plant and to harvest crops. An Aztec calendar stone dug up in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

in 1790 includes information about the months of the year and pictures of the sun god at the center.

Colonial Era

After the

After the Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

was founded, the Spanish brought the scientific culture that dominated Spain to the Viceroyalty of New Spain.Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 13

The Franciscan order

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

founded the first school of higher learning in the Americas, the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

The Colegio de Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco, Mexico City, is the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas and the first major school of interpreters and translators in the New World. It was established by the Franciscans ...

in 1536, at the site of an Aztec school.

The municipal government (''cabildo'') of Mexico City formally requested the Spanish crown to establish a university in 1539. The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico

The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (in es, Real y Pontificia Universidad de México) was founded on 21 September 1551 by Royal Decree signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles I of Spain, in Valladolid, Spain. It is generally co ...

(''Real y Pontificia Universidad de México'') was established in 1551. The university was administered by the clergy and it was the official university of the empire. It provided quality education for the people, and it was a hub of intellectual and religious development in the region. It taught subjects such as physics and mathematics from the perspective of Aristotelian philosophy. Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

philosopher Alonso Gutiérrez

Alonso Gutiérrez, also known as Alonso de la Vera Cruz (c.1507–1584) was a Spanish philosopher and Augustinian, who took the religious name ''da Vera Cruz''. He became a major intellectual figure in New Spain, where he worked from 1535 to ...

in 1553 he became the first professor of the University of Mexico

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ( es, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It is consistently ranked as one of the best universities in Latin America, where it's also the bigges ...

. He wrote ''Physical speculation'', the first scientific text in the Americas, in 1557. By the late 18th century, the university had trained 1,162 doctors, 29,882 bachelors

A bachelor is a man who is not and has never been married.Bachelors are, in Pitt & al.'s phrasing, "men who live independently, outside of their parents' home and other institutional settings, who are neither married nor cohabitating". ().

Etymo ...

, and many lawyers.

Pedro Lopez, a physician to King Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

was sent to New Spain in order to write a medical history of the nation. He spent seven years on his work. He made descriptions and drawings of Novhispanic flora and fauna, and experimented with Indigenous remedies. He returned to Spain with the results of his work in 1577. The book was bound and stored in the archives of the Escorial

El Escorial, or the Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial ( es, Monasterio y Sitio de El Escorial en Madrid), or Monasterio del Escorial (), is a historical residence of the King of Spain located in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, up ...

only to be mostly lost when fire afflicted the palace in 1671. An abridged version however was saved and was published by Federico Cesi

Federico Angelo Cesi (; 26 February 1585 – 1 August 1630) was an Italian scientist, naturalist, and founder of the Accademia dei Lincei. On his father's death in 1630, he became briefly lord of Acquasparta.

Biography

Federico Cesi was ...

. Back in Mexico a Dominican lay brother named Francisco Jiménez translated the abridgement from Latin to Spanish. It was composed of four books: the first three relating to plants, and the fourth relating to animals and minerals.

Alonso López de Hinojosos, the physician at the Royal Hospital of Indians conducted many autopsies during the epidemic of 1576 in order to understand more the nature of the Cocoliztli

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused millions of deaths in New Spain during the 16th-century. The Aztec people called it ''cocoliztli'', Nah ...

disease. He also wrote textbooks on surgery. During that same epidemic, Juan de la Fuente, professor of medicine at the University of Mexico convoked all of the local physicians in order to further understand the disease.

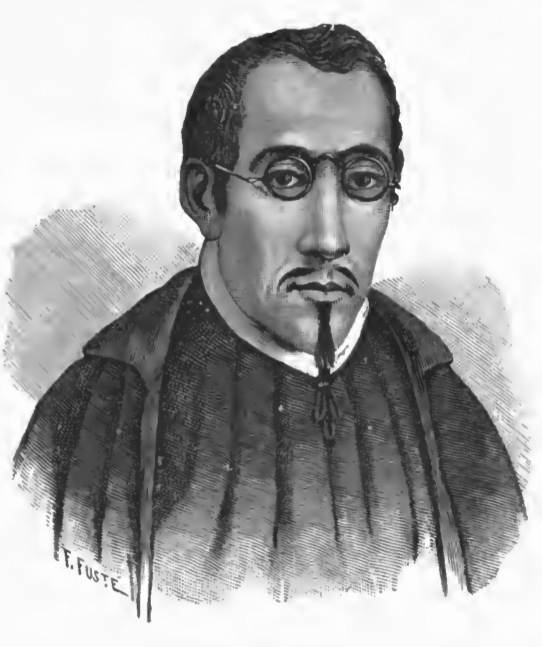

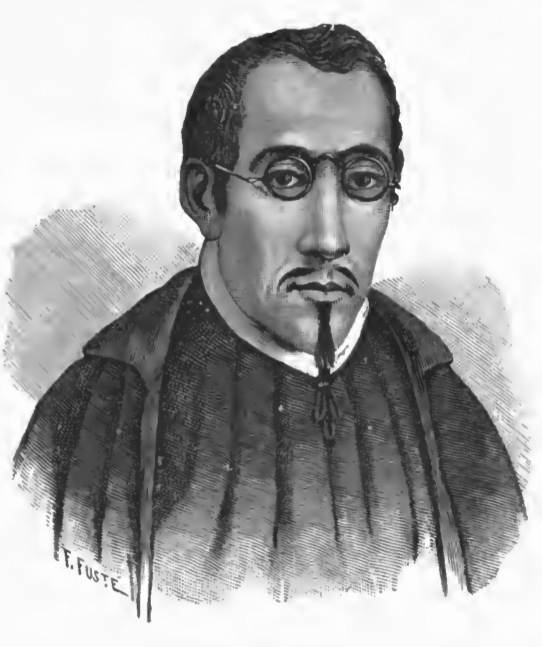

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (August 14, 1645 – August 22, 1700) was one of the first great intellectuals born in the New World - Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico City). He was a criollo patriot, exalting New Spain over Old. ...

was a Mexican Jesuit poet, a philosopher, a mathematician, a historian, and antiquarian. He studied astronomy, physics, and mathematics at Tepotzotlán College. He was at one point invited to visit the court of Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

. He abandoned Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the socia ...

and adopted Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes is of ...

. He also advocated a naturalistic explanation for comets, free from superstition.

In 1693 Viceory Galve nominated Sigüenza to form part of a scientific expedition tasked with exploring the Gulf of Mexico. Siguena accepted and published his findings in a treatise. He also wrote treatises on astronomy and geometry.

Bourbon Reforms

In the early 18th century, theWar of Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

ended with the rule of Spain passing over from the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

over to the French House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

. The new ruling family inaugurated a program of government improvements known as the Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's po ...

which also affected the colonies and inaugurated the era of Spanish American Enlightenment

The ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment, which emphasized reason, science, practicality, clarity rather than obscurantism, and secularism, were transmitted from France to the New World in the eighteenth century, following the establishment of th ...

. Regardless, the 1767 expulsion of Jesuits, who had been key in the fields of Mexican science and education, helped to antagonize the Creoles.Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 15 In 1792 the Seminary of Mining was established. Later it became the College of Mining, in which the first modern physics laboratory in Mexico was established. Andrés Manuel del Río

Andrés Manuel del Río y Fernández (10 November 1764 – 23 March 1849) was a Spanish– Mexican scientist, naturalist and engineer who discovered compounds of ''vanadium'' in 1801. He proposed that the element be given the name ''panchromium' ...

and Fausto Elhuyar

Fausto de Elhuyar (11 October 1755 – 6 February 1833) was a Spanish chemist, and the first to isolate tungsten with his brother Juan José Elhuyar in 1783. He was in charge, under a King of Spain commission, of organizing the School of Mines in ...

arrived from Spain to join the faculty. It taught courses on topography, geodesy, mineralogy, and other sciences. Shortly before a botanical garden had also been established which also taught a course on botany.

Notable scientists during this era included José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez

José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (20 November 1737 – 2 February 1799) was a priest in New Spain, scientist, historian, cartographer, and journalist.

Life and career

He was born in Ozumba in 1737, the child of Felipe de Alzate and María ...

and Andrés Manuel del Río

Andrés Manuel del Río y Fernández (10 November 1764 – 23 March 1849) was a Spanish– Mexican scientist, naturalist and engineer who discovered compounds of ''vanadium'' in 1801. He proposed that the element be given the name ''panchromium' ...

. Río discovered the chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pas ...

in 1801.

During this era Francisco Xavier Gamboa was a jurist who also expressed interest in science. After being tasked with compiling reports for the government of New Spain he studied mathematics and mining and wrote a treatise on mining engineering.

Antonio de León y Gama

Antonio de León y Gama (1735–1802) was a Mexican astronomer, anthropologist and writer. When in 1790 the Aztec calendar stone (also called sun stone) was discovered buried under the main square of Mexico City, he published an essay about it ...

wrote reports on the moons of Jupiter, the climate of New Spain, and helped to precisely calculate the longitude of Mexico. He also wrote a report on the Aztec sun stone

The Aztec sun stone ( es, Piedra del Sol) is a late post-classic Mexica sculpture housed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, and is perhaps the most famous work of Mexica sculpture. It measures in diameter and thick, and wei ...

.

Joaquín Velázquez de León

Joaquín Velázquez de León (16 March 1803 – 8 February 1882) was a 19th-century conservative politician of Mexico who served as the founding Minister of Colonization, Industry and Commerce (1853–1855) in the cabinet of Antonio López de San ...

's scientific reputation earned the praise of Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, p ...

. He studied the works of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

and specialized in mathematics, geodesy, and astronomy.

Velázquez de León built scientific instruments not available in New Spain and accompanied José de Gálvez

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

on his expedition to Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is d ...

. He also made expeditions into the Californias

The Californias (Spanish: ''Las Californias''), occasionally known as The Three Californias or Two Californias, are a region of North America spanning the United States and Mexico, consisting of the U.S. state of California and the Mexican stat ...

where the clear skies of those regions allowed him to make many astronomical observations, including a transit of venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a trans ...

in 1769, which allowed him to measure the distance from the Earth to the sun. Accompanying him on that occasion was Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche

Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche (23 March 1722 – 1 August 1769) was a French astronomer, best known for his observations of the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769.

Early life

Little is known of Chappe's early life. He was born into a distingu ...

, the French priest and geometer. While in the Californias he precisely calculated their longitudes and latitudes. In 1773, he also precisely calculated the longitude and latitude of Mexico City.

Through triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle me ...

between Peñón de los Baños, to Huehuetoca

Huehuetoca is a ''municipio'' (municipality) in State of Mexico, central Mexico, and also the name of its largest town and municipal seat.

Name origins

The name "Huehuetoca" is derived from the Nahuatl ''huehuetocan'', which has several interp ...

, Velázquez de León drew up topographical charts for the region. He was also commissioned to work on projects related to mining by the government of New Spain.

José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez

José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (20 November 1737 – 2 February 1799) was a priest in New Spain, scientist, historian, cartographer, and journalist.

Life and career

He was born in Ozumba in 1737, the child of Felipe de Alzate and María ...

conducted many experiments, regarding electricity and meteorology. In 1789, he recorded observations regarding a rare occurrence of the aurora borealis

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of br ...

in Mexico. He was also an avid naturalist, cataloging many Mexican plants and animals, and studying the migration patterns of birds. He however has also been criticized for not using the nascent Linnaean taxonomy

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

# The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his ''Systema Naturae'' (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus t ...

.

During the reign of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, Alejandro Malaspina

Alejandro Malaspina (November 5, 1754 – April 9, 1810) was a Tuscan explorer who spent most of his life as a Spanish naval officer. Under a Spanish royal commission, he undertook a voyage around the world from 1786 to 1788, then, from 1789 t ...

and Dionisio Alcalá Galiano

Dionisio Alcalá Galiano (8 October 1760 – 21 October 1805) was a Spanish naval officer, cartographer, and explorer. He mapped various coastlines in Europe and the Americas with unprecedented accuracy using new technology such as chronomete ...

and Antonio Valdés y Fernández Bazán

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

were tasked with carrying out expeditions to explore the northwest coast of New Spain.

José Mariano Mociño

José Mariano Mociño Suárez Lozano (24 September 1757 – 12 June 1820), or simply José Mariano Mociño, was a naturalist from New Spain.

After having studied philosophy and medicine, he conducted early research on the botany, geology, and ant ...

studied at the Botanic Garden in 1789. Mociño had accompanied Martín Sessé y Lacasta

Martín Sessé y Lacasta (December 11, 1751 – October 4, 1808) was a Spanish botanist, who relocated to New Spain (now Mexico) during the 18th century to study and classify the flora of the territory.

Background

Sessé studied medicine in Z ...

in the scientific expedition ordered by Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

IV in 1795 tasked with surveying New Spain's plant life. The expedition lasted eight years. Mociño traveled over three thousand leagues ultimately producing a report titled ''Mexican Flora'' which was then sent to the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid

' (Spanish for ''Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid'') is an botanical garden in Madrid (Spain). The public entrance is located at , next to the Prado Museum.

History

The garden was founded on October 17, 1755, by King Ferdinand VI, and i ...

. The Swiss naturalist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss botanist. René Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple of years de Candol ...

was an admirer of the work, and when Mociño travelled to Spain to access his volume, a copy had to be made so that DeCandolle would not have to part with it.

Early Years of Independence

In 1833, PresidentValentín Gómez Farías

Valentín Gómez Farías (; 14 February 1781 – 5 July 1858) was a Mexican physician and liberal politician who became president of Mexico twice, first in 1833, during the period of the First Mexican Republic, and again in 1846, during the ...

, himself a physician decreed the establishment of a School of Medical Sciences. It was ultimately not built due to the Gomez Farias administration being overthrown by a coup shortly afterward, but in 1854 a private medical college was established in Mexico City. Gómez Farías also closed the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico in 1833 as part of his anti-clerical measures.

Certain Mexican presidents in this era had come from a background in the sciences. President Anastasio Bustamante

Anastasio Bustamante y Oseguera (; 27 July 1780 – 6 February 1853) was a Mexican physician, general, and politician who served as president of Mexico three times. He participated in the Mexican War of Independence initially as a royalist befo ...

had been a physician and during a temporary exile in Europe, he had spent some of his time visiting the anatomical collections of Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of ...

and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. President Valentín Gómez Farías

Valentín Gómez Farías (; 14 February 1781 – 5 July 1858) was a Mexican physician and liberal politician who became president of Mexico twice, first in 1833, during the period of the First Mexican Republic, and again in 1846, during the ...

had started out his professional career practicing medicine in Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the list of states of Mexico, state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Me ...

. President Manuel Robles Pezuela

Manuel Robles Pezuela (23 May 1817 - 23 March 1862) was a military engineer, military commander, and eventually interim president of Mexico during a civil war, the War of Reform, being waged between conservatives and liberals, in which he served ...

was a military engineer who had engaged in important geodesic and topographic projects in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the Te ...

. He was also a member of the Mexican Society of Statistics and of the Paris Geographical Society.

The statesman Lucas Alamán

Lucas Ignacio Alamán y Escalada ( Guanajuato, New Spain, October 18, 1792 – Mexico City, Mexico, June 2, 1853) was a Mexican scientist, conservative statesman, historian, and writer. He came from an elite Guanajuato family and was well-tra ...

who served under multiple administrations had come from a background of mining engineering, and in his youth he had studied in Europe under René Just Haüy

René Just Haüy () FRS MWS FRSE (28 February 1743 – 1 June 1822) was a French priest and mineralogist, commonly styled the Abbé Haüy after he was made an honorary canon of Notre Dame. Due to his innovative work on crystal structure and hi ...

, Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, made an early ba ...

, and Louis Jacques Thénard

Louis Jacques Thénard (4 May 177721 June 1857) was a French chemist.

Life

He was born in a farm cottage near Nogent-sur-Seine in the Champagne district

the son of a farm worker. In the post-Revolution French educational system , most boys rec ...

. He had also sought to bring to Mexico the technique of separating silver and gold through the use of sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

in contrast to the old technique of using nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

.

General Pedro García Conde studied mathematics, chemistry, and minerology, at the Mining College in Mexico, and joined the military as an engineer. In 1834, he was named geometer of the boundary commission. In 1838 he was named director of the Military College.

Conde passed sweeping reforms for the military college, establishing courses on descriptive geometry, applied mechanics, astronomy and geodesy. He was Secretary of War in the years leading up to the Mexican American War

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

. He was tasked by a government commission to map the boundary established by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, and made the effort to try to save as much territory as he could for Mexico.

Francisco Díaz Covarrubias studied at the Mining School, and in 1854 he was appointed professor of topography, geodesy, and astronomy. He was part of the team that made the first detailed hydrographic map of the valley of Mexico, and improved upon the Mexican geographic coordinates made by Alexander von Humboldt.

Leopoldo Río de la Loza studied at San Ildefonso College

Colegio de San Ildefonso, currently is a museum and cultural center in Mexico City, considered to be the birthplace of the Mexican muralism movement. San Ildefonso began as a prestigious Jesuit boarding school, and after the Reform War it gain ...

and in 1827 received the title of surgeon. He did not enjoy the field and began studying to work as a pharmacist. He graduated in 1833 and played a role in the efforts against the cholera epidemic which broke out that year. He published articles on mineral and drinking waters, on medication, on Lake Texcoco, and other matters related to public hygiene.

Miguel F. Jiménez after attending medical school began teaching anatomy in 1838. He published an landmark study on spotted fever

A spotted fever is a type of tick-borne disease which presents on the skin. They are all caused by bacteria of the genus ''Rickettsia''. Typhus is a group of similar diseases also caused by ''Rickettsia'' bacteria, but spotted fevers and typhus are ...

colloquially known as ''tabardillo'', in 1846. He continued to publish various treatises on illnesses and conditions throughout his career.

The first industrial exhibition in Mexico opened on November 1, 1849, in Mexico City. In 1849, the exclusive concession to establish telegraph lines was granted to Juan de la Granja, and on December, 1851 the first telegram in Mexico was transmitted from Mexico City to Puebla. The line was extended to Vera Cruz the following year.

During the period of the Second Mexican Empire

The Second Mexican Empire (), officially the Mexican Empire (), was a constitutional monarchy established in Mexico by Mexican monarchists in conjunction with the Second French Empire. The period is sometimes referred to as the Second French i ...

, Emperor Maximilian organized an academy of science and literature. Among its scientific faculty were Leopoldo Río de la Loza, Miguel F. Jiménez, head of the school of medicine, Joaquin de Mier y Teran professor of mathematics at the College of Mining, and the mining engineer Antonio del Castillo

Antonio del Castillo y Saavedra (10 July 1616 – 2 February 1668) was a Spanish Baroque painter, sculptor, and poet.

Biography

Antonio del Castillo y Saavedra was born at Córdoba, Spain.

He trained in painting under his father Agustín ...

.

Maximilian's Minister of Public Works Luis Robles Pezuela presented the government a report on the state of Mexico's telegraphic network which then included three lines. One connecting Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

to Tehuacán "By faith and hope"

,

, image_map =

, mapsize = 300 px

, map_caption = Location of Tehuacán within the state of Puebla.

, image_map1 = Puebla en México.svg

, mapsize1 = 300 px

, ma ...

, and two private lines: one of them connecting Bagdad to Matamoros. Maximilian also had a private line built, connecting the Chapultepec Castle

Chapultepec Castle ( es, Castillo de Chapultepec) is located on top of Chapultepec Hill in Mexico City's Chapultepec park. The name ''Chapultepec'' is the Nahuatl word ''chapoltepēc'' which means "on the hill of the grasshopper". The castle has s ...

to the National Palace Buildings called National Palace include:

*National Palace (Dominican Republic), in Santo Domingo

*National Palace (El Salvador), in San Salvador

*National Palace (Ethiopia), in Addis Ababa; also known as the Jubilee Palace

*National Palace (Guatema ...

. The Emperor made efforts to expand this network.

A railroad connecting Veracruz to Mexico City was first proposed in 1830. The government granted an ill-fated concession to begin the project in 1837. After more ill-fated efforts substantial progress was finally made in 1857 after a concession had been granted to Antonio Escandon, but it was interrupted by the nation's ongoing civil wars. Engineers commissioned by Emperor Maximilian completed 134 miles before the fall of the Second Mexican Empire in 1867. The long-awaited Mexico City to Veracruz railroad line was finally inaugurated on January 1, 1873.

Porfiriato

Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

' ascension to the presidency in 1876 brought an end to the Mexican civil wars which had repeatedly broken out since independence had first been achieved. Mexico entered upon a period of stability and industrialization which also contributed to advances in science and technology. The influence of French Positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

led to a renaissance of scientific activity in Mexico.

Chief among the positivists was Gabino Barreda

Gabino Barreda (born Puebla, 1818 – died Mexico City 1881) was a Mexican physician and philosopher oriented to French positivism.

After participating in the Mexican–American War defending his country as a volunteer, he studied medicine in ...

who founded the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria

The Escuela Nacional Preparatoria ( en, National Preparatory High School) (ENP), the oldest senior High School system in Mexico, belonging to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), opened its doors on February 1, 1868. It was founded ...

and became its first director. The medical faculty would eventually include the physicians Manuel Carmona y Valle, Eduardo Liceaga

Eduardo Liceaga (1839–1920) was a Mexican physician known as the "most distinguished hygienist of late-nineteenth century Mexico". He was involved in the establishment of the General Hospital of Mexico.

Early life and education

Liceaga was bor ...

, and Rafael Lavista y Rebolla, the oculist Joaquín Vértiz, and the pediatrician Miguel Otero y Arce

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael. It may refer to:

Places

* Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands

* São Miguel (disam ...

. The faculty of physical scientists would eventually include the chemist Andrés Almaraz, and the engineer Mariano de la Bárcena

Mariano de la Bárcena (July 22, 1842 – April 10, 1899) was a Mexican engineer, botanist, politician, and interim Governor of Jalisco. He was from Ameca, Jalisco.

Biography

Mariano Santiago de Jesús de la Bárcena y Ramos was born to Don José ...

. The faculty of mathematics would eventually include Jose Joaquin Terrazas, and the engineer Leandro Fernández Imas.

A national observatory at Chapultepec was decreed in December, 1876 and inaugurated on May, 1878. Its first director was Francisco Díaz Covarrubias. The observatory included a meteorological and magnetic observatory and maintained correspondence with international observatories and scientific organizations. In 1877 a meteorological observatory was established which also maintained correspondence with international observatories. Covarrubias was appointed president over a scientific commission tasked with travelling to Japan to observe the 1874 transit of Venus

The 1874 transit of Venus, which took place on 9 December 1874 (01:49 to 06:26 UTC), was the first of the pair of transits of Venus that took place in the 19th century, with the second transit occurring eight years later in 1882. The previous p ...

. A geological society was established in 1875.

The Federal Telegraphic Office during this time provided meteorological observations. The Academy of Medicine annually awarded prizes to the authors of the best scientific reports. A Pedro Escobedo Society also awarded prizes for scientific accomplishments. The Mexican government made efforts to reward scientific discovery by sending relevant scientists to Europe so that they could gain more attention for their work.

The proliferation of railroads stimulated the development of Mexican industry by giving it access to the latest machinery.

A Ministry of Communications and Public Works was established during this time, and began a program of building lighthouses for Mexican ports. The Ministry also commissioned improvements to the Veracruz Harbor. Smaller improvements were made to the Atlantic ports of Progreso, Campeche

Campeche (; yua, Kaampech ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Campeche), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by ...

, and Tuxpam. The only Pacific ports to be improved during this time were Manzanillo and Salina Cruz

Salina Cruz is a major seaport on the Pacific coast of the Mexican state of Oaxaca. It is the state's third-largest city and is the municipal seat of the municipality of the same name.

It is part of the Tehuantepec District in the west of the I ...

.

Improvements to the nation's telegraph network continued during this time. A school of telegraphy was established along with workshops to repair the network. Experiments were made in wireless telegraphy in order to bridge the Sea of Cortés

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja C ...

. By 1902, the network spanned over 40,000 kilometers of wire with 379 stations.

A telephone network began to be built in Mexico during this time. By the beginning of the 20th century telephone networks between cities spanned over 27,000 kilometers of wire and included almost 3000 devices. Every state in Mexico was included in the network.

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Manuel Mondragón

Manuel Mondragón (1859–1922) was a Mexican military officer who played a prominent role in the Mexican Revolution. He graduated from the Mexican Military Academy as an artillery officer in 1880. He designed the world’s first gas-operated s ...

invented the Mondragón rifle

The Mondragón rifle refers to one of two rifle designs developed by Mexican artillery officer General Manuel Mondragón. These designs include the straight-pull bolt-action M1893 and M1894 rifles, and Mexico's first self-loading rifle, the M1908 ...

during this time. These designs include the straight-pull bolt-action M1893 and M1894 rifles, and Mexico's first self-loading rifle

A self-loading rifle or autoloading rifle is a rifle with an action using a portion of the energy of each cartridge fired to load another cartridge. Self-loading pistols are similar, but intended to be held and fired by a single hand, while rifles ...

, the M1908 - the first of the designs to see combat use.

Science and technology in the 20th century

During the 20th century, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. New universities and research institutes were established. The

During the 20th century, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. New universities and research institutes were established. The National Autonomous University of Mexico

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ( es, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It is consistently ranked as one of the best universities in Latin America, where it's also the bigges ...

(''Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México'', ''UNAM'') was officially established in 1910, and the university become one of the most important institutes of higher learning in Mexico.Summerfield, Devine & Levi (1998), p. 285 UNAM provides education in science, medicine, and engineering. Many scientific institutes and new institutes of higher learning, such as National Polytechnic Institute

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

(founded in 1936), were established during the first half of the 20th century. Most of the new research institutes were created within UNAM. Twelve institutes were integrated into UNAM from 1929 to 1973.Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 18

Mexican scientists, physicians, and intellectuals were involved in the movement to shape Mexico's population through eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

. The ''Sociedad Mexicana de Eugenesia'' was founded in 1931, and was concerned with mental disabilities, prison reform, tuberculosis, syphilis, alcoholism, sexual education, mestizaje

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

, prostitution, puericulture, (scientific child-rearing), and single mothers. The society advocated for maternal assistance, eradication of juvenile delinquency, and incorporation of its ideas into the functioning of schools, prisons, and public health administration. It succeeding in having established a medical clinic, the Hereditary Health Counseling Center, for workers. The organization published the journal ''Eugenesia'' until 1954.

In the 1930s

In the 1930s Manuel Sandoval Vallarta

Manuel Sandoval Vallarta (11 February 1899 – 18 April 1977) was a Mexican physicist. He was a Physics professor at both MIT and the Institute of Physics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Biography

Sandoval Vallart ...

a Mexican physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

worked on Cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

research and in 1943 to 1946, he divided his time between MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the mo ...

and UNAM

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ( es, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It is consistently ranked as one of the best universities in Latin America, where it's also the bigges ...

as a full-time professor.

On August 31, 1946, Guillermo González Camarena

Guillermo González Camarena (17 February 1917 – 18 April 1965) was a Mexican electrical engineer who was the inventor of a color-wheel type of color television.

Early life

González Camarena was born in Guadalajara, Mexico. He was the younge ...

sent his first color transmission from his lab in the offices of The Mexican League of Radio Experiments, at Lucerna St. #1, in Mexico City. The video signal was transmitted at a frequency of 115 MHz. and the audio in the 40-meter band. González Camarena was a Mexican engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

who was the inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

of a color-wheel type of color television, and who also introduced color television to Mexico.

Mexico was in the forefront of the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production. These changes in agriculture began in developed countrie ...

, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

and developed by Norman Borlaug

Norman Ernest Borlaug (; March 25, 1914September 12, 2009) was an American agronomist who led initiatives worldwide that contributed to the extensive increases in agricultural production termed the Green Revolution. Borlaug was awarded multiple ...

, who later won the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

for his work. The aim was to increase the productivity of Mexican agriculture through the development of new strains of seeds. Mexico founded the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known - even in English - by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT for ''Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo'') is a non-profit research-for-development organization that develops im ...

to further this scientific work.

In the 1950s, the wild yam known as '' barbasco'' was discovered to contain steroid hormones that could affect human fertility and led to the development of The Pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. The pill contains two important hormones: progesti ...

. A Mexican research company, Syntex Laboratorios Syntex SA (later Syntex Laboratories, Inc.) was a pharmaceutical company formed in Mexico City in January 1944 by Russell Marker, Emeric Somlo, and Federico Lehmann to manufacture therapeutic steroids from the Mexican yams called ''cabe ...

was founded and began producing oral contraceptives. The Mexican government under President Luis Echeverría

Luis Echeverría Álvarez (; 17 January 1922 – 8 July 2022) was a Mexican lawyer, academic, and politician affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), who served as the 57th president of Mexico from 1970 to 1976. Previously, ...

created a state-run company, Proquivemex, to control and regulate the industry.

In 1959, the

In 1959, the Mexican Academy of Sciences

The Mexican Academy of Sciences ''(Academia Mexicana de Ciencias)'' is a non-profit organization comprising over 1800 distinguished Mexican scientists, attached to various institutions in the country, as well as a number of eminent foreign coll ...

(''Academia Mexicana de Ciencias'') was established as a non-governmental, non-profit organization of distinguished scientists. The academy has grown in membership and influence, and it represents a strong voice of scientists from different fields, mainly in science policy.

By 1960, science was institutionalized in Mexico. It was viewed as a legitimate endeavor by the Mexican society. Guillermo Haro

Guillermo Haro Barraza (; 21 March 1913 – 26 April 1988) was a Mexican astronomer. Through his own astronomical research and the formation of new institutions, Haro was influential in the development of modern observational astronomy in M ...

through his own astronomical research and the formation of new institutions, Haro was influential in the development of modern observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical m ...

in Mexico. Internationally, he is best known for his contribution to the discovery of Herbig–Haro object

Herbig–Haro (HH) objects are bright patches of nebula, nebulosity associated with newborn stars. They are formed when narrow jets of partially plasma (physics), ionised gas ejected by stars collide with nearby clouds of gas and dust at several ...

s.

In 1961, the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

was established as a center for graduate studies in subjects such as biology, mathematics, and physics. In 1961, the institute began its graduate programs in physics and mathematics and schools of science were established in Mexican states of Puebla

Puebla ( en, colony, settlement), officially Free and Sovereign State of Puebla ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its cap ...

, San Luis Potosí

San Luis Potosí (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of San Luis Potosí ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de San Luis Potosí), is one of the 32 states which compose the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 58 municipalities and i ...

, Monterrey

Monterrey ( , ) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León, Mexico, and the third largest city in Mexico behind Guadalajara and Mexico City. Located at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental, the city is anchor ...

, Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, and Michoacán

Michoacán, formally Michoacán de Ocampo (; Purépecha: ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Michoacán de Ocampo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of ...

. The Academy for Scientific Research was established in 1968 and the National Council of Science and Technology was established in 1971.

Ricardo Miledi

Ricardo Miledi (15 September 1927 – 18 December 2017) was a Mexican neuroscientist known for his work deciphering the role of calcium in neurotransmitter release. He also helped to develop a technique for studying native receptors in frog oocyte ...

, one of the ten most quoted neuro-biologists of all time, was born in Mexico, D.F. in 1927. His career in science began in 1955 when, just before graduating in medicine at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM), he joined one of the most active research groups in his country, part of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología (the National Institute of Cardiology).

Many of Professor Miledi's studies and breakthroughs in Neurobiology, especially those related to the mechanisms of synaptic and neuromuscular transmission

A neuromuscular junction (or myoneural junction) is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

It allows the motor neuron to transmit a signal to the muscle fiber, causing muscle contraction.

Muscles require innervation t ...

, are considered to be classic throughout the world. Over 450 publications are the tangible product of forty years of research devoted to the main to the primary functions of the nervous system: the transmission of information between cells. He has been a member of the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

since 1980 and entered the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1986. In 1999 Miledi was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award

The Princess of Asturias Awards ( es, Premios Princesa de Asturias, links=no, ast, Premios Princesa d'Asturies, links=no), formerly the Prince of Asturias Awards from 1981 to 2014 ( es, Premios Príncipe de Asturias, links=no), are a series of a ...

for Technical and Scientific Research.

He has been Professor of Biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

and distinguished professor of the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, ...

since 1984. He also leads a neurobiology laboratory in UNAM in Querétaro, México.

In 1985 Rodolfo Neri Vela

Rodolfo Neri Vela (born 19 February 1952) is a Mexican scientist and astronaut who flew aboard a NASA Space Shuttle mission in the year 1985. He is the second Latin American to have traveled to space.

Personal

Neri was born in Chilpancingo, Gue ...

became the first Mexican citizen to enter space as part of the STS-61-B

STS-61-B was NASA's 23rd Space Shuttle mission, and its second using Space Shuttle ''Atlantis''. The shuttle was launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on November 26, 1985. During STS-61-B, the shuttle crew deployed three communications ...

mission.

In 1995 Mexican chemist Mario J. Molina

Mario José Molina-Pasquel Henríquez (19 March 19437 October 2020), known as Mario Molina, was a Mexican chemist. He played a pivotal role in the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole, and was a co-recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemis ...

shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

with Paul J. Crutzen

Paul Jozef Crutzen (; 3 December 1933 – 28 January 2021) was a Dutch meteorologist and atmospheric chemist. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995 for his work on atmospheric chemistry and specifically for his efforts in studying ...

, and F. Sherwood Rowland

Frank Sherwood "Sherry" Rowland (June 28, 1927 – March 10, 2012) was an American Nobel laureate and a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Irvine. His research was on atmospheric chemistry and chemical kinetics. His be ...

for their work in atmospheric chemistry

Atmospheric chemistry is a branch of atmospheric science in which the chemistry of the Earth's atmosphere and that of other planets is studied. It is a multidisciplinary approach of research and draws on environmental chemistry, physics, meteoro ...

, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone

Ozone (), or trioxygen, is an inorganic molecule with the chemical formula . It is a pale blue gas with a distinctively pungent smell. It is an allotrope of oxygen that is much less stable than the diatomic allotrope , breaking down in the lo ...

. Molina, an alumnus of UNAM, became the first Mexican citizen to win the Nobel Prize in science.

Evangelina Villegas

Evangelina Villegas (October 24, 1924 – April 24, 2017) was a Mexican cereal biochemist whose work with maize led to the development of quality protein maize (QPM). She and her colleague from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Cent ...

work with maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

led to the development of quality protein maize

Quality Protein Maize (QPM) is a family of maize varieties. QPM grain contains nearly twice as much lysine and tryptophan, amino acids that are essential for humans and monogastric animals but are limiting amino acids in grains. QPM is a product o ...

(QPM). Surinder Vasal

Surinder Vasal is an Indian geneticist and plant breeder, known for his contributions in developing a maize variety with higher content of usable protein. He was born on 12 April 1938 in Amritsar in the Indian state of Punjab and received a PhD ...

, shared the 2000 World Food Prize

The World Food Prize is an international award recognizing the achievements of individuals who have advanced human development by improving the quality, quantity, or availability of food in the world. Conceived by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Nor ...

for this achievement. Villegas was the first woman to ever receive the World Food Prize.

The Large Millimeter Telescope