History of public relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Most textbooks date the establishment of the "Publicity Bureau" in 1900 as the start of the modern

Although the term "public relations" was not yet developed, academics like

Although the term "public relations" was not yet developed, academics like

According to Noel Turnbull, an adjunct professor from

According to Noel Turnbull, an adjunct professor from

The Publicity Bureau was the first PR agency and was founded by former Boston journalists, including Ivy Lee. Ivy Lee is sometimes called the father of PR and was influential in establishing it as a professional practice. In 1906, Lee published a Declaration of Principles, which said that PR work should be done in the open, should be accurate and cover topics of public interest. According to historian Eric Goldman, the declaration of principles marked the beginning of an emphasis on informing, rather than misleading, the public. Ivy Lee is also credited with developing the modern

The Publicity Bureau was the first PR agency and was founded by former Boston journalists, including Ivy Lee. Ivy Lee is sometimes called the father of PR and was influential in establishing it as a professional practice. In 1906, Lee published a Declaration of Principles, which said that PR work should be done in the open, should be accurate and cover topics of public interest. According to historian Eric Goldman, the declaration of principles marked the beginning of an emphasis on informing, rather than misleading, the public. Ivy Lee is also credited with developing the modern

Can the professionalisation of the UK PR industry make it more trustworthy?

, Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 9 Iss: 1 pp. 56 – 64 Bernays was influenced by Freud's theories about the subconscious. He authored several books, including ''Crystallizing Public Opinion'' (1923), ''Propaganda'' (1928), and In 1929, Edward Bernays helped the

In 1929, Edward Bernays helped the

Edward Clarke and Bessie Tyler were influential in growing the

Edward Clarke and Bessie Tyler were influential in growing the

Institute for Public Relations

was founded in 1956. The

Ewen, Stuart. ''PR! - A Social History of Spin'' (1996), popular history from the left

* Fones-Wolf, Elizabeth. "Creating a favorable business climate: Corporations and radio broadcasting, 1934 to 1954." ''Business History Review'' 73#2 (1999): 221-255.

* Gower, Karla. "US corporate public relations in the progressive era." ''Journal of Communication Management'' 12#4 (2008): 305-318.

* Heath, Robert L., ed. ''Encyclopedia of public relations'' (2nd ed. Sage Publications, 2013)

* John, Burton St. "The case for ethical propaganda within a democracy: Ivy Lee's successful 1913–1914 railroad rate campaign." ''Public Relations Review'' 32.3 (2006): 221-228.

* John, Burton St. and Margot Opdycke Lamme. ''Pathways to Public Relations: Histories of Practice and Profession'' (2014)

* Lamme, Margot Opdycke, and Karen Miller Russell. "Removing the spin: Toward a new theory of public relations history." ''Journalism and Communication Monographs'' 11#.4 (2010)

* Miller, David, and William Dinan. "The rise of the PR industry in Britain, 1979-98." ''European Journal of Communication'' 15#.1 (2000): 5-35.

* Miller, David, and William Dinan. ''A century of spin: How public relations became the cutting edge of corporate power'' (Pluto Press, 2007), A view from the left

* Miller, Karen S. "US Public Relations History: Knowledge and Limitations." ''Communication yearbook'' 23 (2012): 381+

* Russell, Karen Miller, and Carl O. Bishop. "Understanding Ivy Lee's declaration of principles: US newspaper and magazine coverage of publicity and press agentry, 1865–1904." ''Public Relations Review'' 35.2 (2009): 91-101

online

* Watson, Tom. "The evolution of public relations measurement and evaluation." ''Public Relations Review'' 38#.3 (2012): 390-398

online

public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

(PR) profession. Of course, there were many early forms of public influence and communications

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inquir ...

management in history. Basil Clarke is considered the founder of the public relations profession in Britain with his establishment of Editorial Services in 1924. Academic Noel Turnball points out that systematic PR was employed in Britain first by religious evangelicals and Victorian reformers, especially opponents of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. In each case the early promoters focused on their particular movement and were not for hire more generally.

Propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

was used by both sides to rally domestic support and demonize enemies during the First World War. PR activists entered the private sector in the 1920s. Public relations became established first in the U.S. by Ivy Lee or Edward Bernays

Edward Louis Bernays ( , ; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an American theorist, considered a pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, and referred to in his obituary as "the father of public relations". His best-known ca ...

, then spread internationally. Many American companies with PR departments spread the practice to Europe after 1948 when they created European subsidiaries as a result of the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

.

The second half of the twentieth century was the professional development building era of public relations. Trade associations, PR news magazines, international PR agencies, and academic principles for the profession were established. In the early 2000s, press release services began offering social media press releases. The Cluetrain Manifesto

''The Cluetrain Manifesto'' is a work of business literature collaboratively authored by Rick Levine, Christopher Locke, Doc Searls, and David Weinberger. It was first posted to the web in 1999 as a set of ninety-five theses, and was published as ...

, which predicted the impact of social media in 1999, was controversial in its time, but by 2006, the effect of social media and new internet technologies became broadly accepted.

Ancient origins

Although the term "public relations" was not yet developed, academics like

Although the term "public relations" was not yet developed, academics like James E. Grunig

James E. Grunig (born April 18, 1942) is a public relations theorist, Professor Emeritus for the Department of Communication at the University of Maryland.Curriculum vita, University of Maryland Accessed July 16, 2017

Biography

Grunig was born ...

and Scott Cutlip

Scott Munson Cutlip (July 15, 1915 in Buckhannon, West Virginia – August 18, 2000 in Madison, Wisconsin) was a pioneer in public relations education.

Biography

Cutlip was born in Buckhannon, West Virginia, the son of Okey Scott Cutlip and Janet ...

identified early forms of public influence and communications management in ancient civilizations. According to Edward Bernays

Edward Louis Bernays ( , ; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an American theorist, considered a pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, and referred to in his obituary as "the father of public relations". His best-known ca ...

, one of the pioneers of PR, "The three main elements of public relations are practically as old as society: informing people, persuading people, or integrating people with people." Scott Cutlip said historic events have been defined as PR retrospectively, "a decision with which many may quarrel."

A clay tablet found in ancient Iraq that promoted more advanced agricultural techniques is sometimes considered the first known example of public relations. Babylonian, Egyptian and Persian leaders created pyramids, obelisks and statues to promote their divine right to lead. Additionally, claims of magic or religious authority were used to persuade the public of a king or pharaoh's right to rule.

Ancient Greek cities produced sophisticated rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

, as analyzed by Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education throu ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. In Greece there were advocates for hire called "sophists

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ' ...

". Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and others said sophists were dishonest and misled the public, while the book "''Public Relations as Communication Management''" said they were "largely an ethical lot" that "used the principles of persuasive communication." In Egypt court advisers consulted pharaohs to speak honestly and scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

s documented a pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

's deeds. In Rome, Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

wrote the first campaign biography promoting his military successes. He also commissioned newsletters and poems to support his political position. In medieval Europe, craftsmen organized into guilds that managed their collective reputation. In England, Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

s acted as mediators between rulers and subjects.

Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

's recruitment for the crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

is also sometimes referred to as a public relations effort. Pope Gregory XV

Pope Gregory XV ( la, Gregorius XV; it, Gregorio XV; 9 January 15548 July 1623), born Alessandro Ludovisi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 February 1621 to his death in July 1623.

Biography

Early life

Al ...

founded the term "propaganda" when he created ''Congregatio de Propaganda'' ("congregation for propagating the faith"), which used trained missionaries to spread Christianity. The term did not carry negative connotations until it was associated with government publicity around World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In the early 1200s, Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

was created as a result of Stephen Langton

Stephen Langton (c. 1150 – 9 July 1228) was an English Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and Archbishop of Canterbury between 1207 and his death in 1228. The dispute between King John of England and Pope Innocent III over his ...

lobbying English barons to insist King John recognize the authority of the church.

Antecedents

Explorers likeMagellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the East ...

, Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

used exaggerated claims of grandeur to entice settlers to come to the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

. For example, in 1598, a desolate swampy area of Virginia was described by Captain Arthur Barlowe

Arthur Barlowe (1550 – 1620) was one of two British captains (the other was Philip Amadas) who, under the direction of Sir Walter Raleigh, left England in 1584 to find land in North America to claim for Queen Elizabeth I of England. Hiaccoun ...

as follows: "The soil is the most plentiful, sweet, fruitful and wholesome of all the world." When colonists wrote back to Europe about the hardships of colonizing Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, including the death toll caused by conflicts with Indians, pamphlets with anonymous authors were circulated to reassure potential settlers and rebuke criticisms.

The first newsletter and the first daily newspaper were founded in Germany in 1609 and 1615 respectively. Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

of France had pamphlets made that supported his policies and attacked his political opposition. The government also created a publicity bureau called Information and Propaganda and a weekly newspaper originally controlled by the French government, The Gazette

The Gazette (stylized as the GazettE), formerly known as , is a Japanese visual kei rock band, formed in Kanagawa in early 2002.''Shoxx'' Vol 106 June 2007 pg 40-45 The band is currently signed to Sony Music Records.

Biography 2002: Conception a ...

. In the mid-1600s both sides of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

conflict used pamphlets to attack or defend the monarchy respectively. Poet John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

wrote anonymous pamphlets advocating for ideas such as liberalizing divorce, the establishment of a republic and the importance of free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

. A then-anonymous pamphlet in 1738 by Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

was influential in criticizing the freemasons

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and advocating for an alliance between the British, Dutch and Austrian governments.

In 1641, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

sent three preachers to England to raise money for missionary activities among the Indians. To support the fund-raising, the University produced one of the earliest fund-raising brochures, ''New England's First Fruits''. An early version of the press release was used when King's College (now Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

), sent out an announcement of its 1758 graduation ceremonies and several newspapers printed the information. Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

was the first university to make it a routine practice of supplying newspapers with information about activities at the college.

According to Noel Turnbull, an adjunct professor from

According to Noel Turnbull, an adjunct professor from RMIT University

RMIT University, officially the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology,, section 4(b) is a public research university in Melbourne, Australia.

Founded in 1887 by Francis Ormond, RMIT began as a night school offering classes in art, scien ...

, more systematic forms of PR began as the public started organizing for social and political movements. The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

was established in England in 1787. It published books, posters and hosted public lectures in England advocating against slavery. Industries that relied on slavery attempted to persuade the middle-class that it was necessary and that slaves had humane living conditions. The Slave Trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was abolished in 1807

Events

January–March

* January 7 – The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland issues an Order in Council prohibiting British ships from trading with France or its allies.

* January 20 – The Sierra Leone Company, faced with ...

. In the U.S., the movement to abolish slavery began in 1833 with the establishment of the American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this socie ...

, using tactics adopted from the British abolitionist movement. According to Edward Bernays

Edward Louis Bernays ( , ; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an American theorist, considered a pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, and referred to in his obituary as "the father of public relations". His best-known ca ...

, the U.S. abolitionist movement used "every available device of communication, appeal and action," such as petitions, pamphlets, political lobbying, local societies, and boycotts. The South responded by defending slavery on the basis of economics, religion and the constitution. In some cases propaganda promoting the abolition of slavery was forbidden in The South and abolitionists were killed or jailed. Public relations also played a role in abolitionist movements in France, Australia and in Europe.

The Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

has been called a "public relations event" or pseudo event

A media event, also known as a pseudo-event, is an event, activity, or experience conducted for the purpose of media publicity. It may also include any event that is covered in the mass media or was hosted largely with the media in mind.

In media ...

, in that it was a staged event intended to influence the public. Pamphlets such as ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arg ...

'' (1775–76) and ''The American Crisis

''The American Crisis'', or simply ''The Crisis'', is a pamphlet series by eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosopher and author Thomas Paine, originally published from 1776 to 1783 during the American Revolution. Thirteen numbered pamphlets w ...

'' (1776 to 1783) were used to spread anti-British propaganda in the United States, as well as the slogan "taxation without representation is tyranny." After the revolution was won, disagreements broke out regarding the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. Supporters of the constitution sent letters now called the Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The c ...

to major news outlets, which helped persuade the public to support the constitution. Exaggerated stories of Davy Crockett

David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier, and politician. He is often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier". He represented Tennessee in the U.S. House of ...

and the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

were used to persuade the public to fight the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

and to migrate west in the U.S. respectively.

Author Marvin Olasky said public relations in the 1800s was spontaneous and de-centralized. In the 1820s, Americans wanted to disprove the perspective of French aristocrats that the American democracy run by "the mob" had "no sense of history, no sense of gratitude to those who had served it, and no sense of the meaning of 'virtue'". To combat this perception, French aristocrat Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, who helped fund the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, was invited to a tour of the United States. Each community he visited created a committee to welcome him and promote his visit. In the mid-1800s P. T. Barnum founded the American Museum and the Barnum and Bailey Circus. He became well known for publicizing his circus using manipulative techniques. For example, he announced that his museum would exhibit a 161-year-old woman, who had been Washington's nurse, then produced an elderly woman and a forged birth certificate.

In the 1860s, the major railway companies building the Transcontinental Railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

(Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

in Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

, and the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

in New York City) engaged in "sophisticated and systematic corporate public relations" in order to raise $125 million needed to construct the 1,776-mile-long railroad. To raise the money, the companies needed to maintain "an image attractive to potential bond buyers, nd maintain relationshipswith members of Congress, the California state legislature, and federal regulators; with workers and potential workers; and with journalists."

Early environmental campaigning groups like the Coal Abatement Society and the Congo Reform Association

The Congo Reform Association (CRA) was a political and Humanitarianism, humanitarian Activism, activist group that sought to promote reform of the Congo Free State, a private territory in Central Africa under the Absolute monarchy, absolute sovere ...

were formed in the late-1800s. In the late 1800s many of the now-standard practices of media relations, such as conducting interviews and press conferences emerged. Industrial firms began to promote their public image. The German steel and armaments company Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krupp ...

created the first corporate press department in 1870 to write articles, brochures and other communications advertising the firm. The first US corporate PR department was established in 1889 by Westinghouse Electric Corporation

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was renamed "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in ...

.Reddi (2010). Effective Public Relations And Media Strategy. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 53. Retrieved February 11, 2013. "The first public relations department was created by the inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse in 1889 when he hired two men to publicize his pet project,alternating current (AC) electricity." The first appearance of the term "public relations" was in the ''1897 Year Book of Railway Literature''.

Origins as a profession

The book ''Today's Public Relations: An Introduction'' says that, although experts disagree on public relations' origins, many identify the early 1900s as its beginning as a paid profession. According to Barbara Diggs-Brown, an academic with theAmerican University School of Communication

The School of Communication (SOC) at American University is accredited by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications. The school offers six undergraduate majors: communication studies, journalism, public relations a ...

, the PR field anchors its work in historical events in order to improve its perceived validity, but it didn't begin as a professional field until around 1900. Scott Cutlip

Scott Munson Cutlip (July 15, 1915 in Buckhannon, West Virginia – August 18, 2000 in Madison, Wisconsin) was a pioneer in public relations education.

Biography

Cutlip was born in Buckhannon, West Virginia, the son of Okey Scott Cutlip and Janet ...

said, "we somewhat arbitrarily place the beginnings of the public relations vocation with the establishment of The Publicity Bureau in Boston in mid-1900." He explains that the origins of PR cannot be pinpointed to an exact date, because it developed over time through a series of events. Most textbooks on public relations say that it was first developed in the United States, before expanding globally; however, Jacquie L'Etang, an academic from the United Kingdom, said it was developed in the UK and the US simultaneously. Noel Turnball claims it began as a professional field in the 18th and 19th century with British evangelicals and Victorian reformers. According to academic Betteke Van Ruler, PR activities didn't begin in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

as a professional field until the 1920s.

According to Goldman, from around 1903 to 1909 "many newspapers and virtually all mass-circulation magazines featured detailed, indignant articles describing how some industry fleeced its stockholders, overcharged the public or corrupted politics." The public became abruptly more critical of big business. The anti-corporate and pro-reform sentiment of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

was reflected in newspapers, which were dramatically increasing in circulation as the cost of paper decreased. Public relations was founded, in part, to defend corporate interests against sensational and hyper-critical news articles. It was also influential in promoting consumerism

Consumerism is a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts. With the Industrial Revolution, but particularly in the 20th century, mass production led to overproduction—the su ...

after the emergence of mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and ba ...

.

Early pioneers

The Publicity Bureau was the first PR agency and was founded by former Boston journalists, including Ivy Lee. Ivy Lee is sometimes called the father of PR and was influential in establishing it as a professional practice. In 1906, Lee published a Declaration of Principles, which said that PR work should be done in the open, should be accurate and cover topics of public interest. According to historian Eric Goldman, the declaration of principles marked the beginning of an emphasis on informing, rather than misleading, the public. Ivy Lee is also credited with developing the modern

The Publicity Bureau was the first PR agency and was founded by former Boston journalists, including Ivy Lee. Ivy Lee is sometimes called the father of PR and was influential in establishing it as a professional practice. In 1906, Lee published a Declaration of Principles, which said that PR work should be done in the open, should be accurate and cover topics of public interest. According to historian Eric Goldman, the declaration of principles marked the beginning of an emphasis on informing, rather than misleading, the public. Ivy Lee is also credited with developing the modern press release

A press release is an official statement delivered to members of the news media for the purpose of providing information, creating an official statement, or making an announcement directed for public release. Press releases are also considere ...

and the "two-way-street" philosophy of both listening to and communicating with the public. In 1906, Lee helped facilitate the Pennsylvania Railroad's first positive media coverage after inviting press to the scene of a railroad accident, despite objections from executives. At the time, secrecy about corporate operations was common practice. Lee's work was often identified as spin or propaganda. In 1913 and 1914, the mining union was blaming the Ludlow Massacre, where on-strike miners and their families were killed by state militia, on the Rockefeller family and their coal mining operation, The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. On the Rockefeller family's behalf, Lee published bulletins called "Facts Concerning the Struggle in Colorado for Industrial Freedom," which contained false and misleading information. Lee warned that the Rockefellers were losing public support and developed a strategy that Junior followed to repair it. It was necessary for Junior to overcome his shyness, go personally to Colorado to meet with the miners and their families, inspect the conditions of the homes and the factories, attend social events, and especially to listen closely to the grievances. This was novel advice, and attracted widespread media attention, which opened the way to resolve the conflict, and present a more humanized versions of the Rockefellers. In response the labor press said Lee "twisted the facts" and called him a "paid liar," a "hired slanderer," and a "poisoner of public opinion." By 1917, Bethlehem Steel company announced it would start a publicity campaign against perceived errors about them. The Y.M.C.A. opened a new press secretary. AT&T and others also started their first publicity programs.

Edward Bernays

Edward Louis Bernays ( , ; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an American theorist, considered a pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, and referred to in his obituary as "the father of public relations". His best-known ca ...

, a nephew of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

, is also sometimes referred to as the father of PR and the profession's first theorist for his work in the 1920s. He took the approach that audiences had to be carefully understood and persuaded to see things from the client's perspective. He wrote the first textbook on PR and taught the first college course at New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

in 1923. Bernays also first introduced the practice of using front groups in order to protect tobacco interests. In the 1930s he started the first vocational course in PR.Natasha Tobin, (2005),Can the professionalisation of the UK PR industry make it more trustworthy?

, Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 9 Iss: 1 pp. 56 – 64 Bernays was influenced by Freud's theories about the subconscious. He authored several books, including ''Crystallizing Public Opinion'' (1923), ''Propaganda'' (1928), and

The Engineering of Consent

"The Engineering of Consent" is an essay by Edward Bernays first published in 1947, and a #Book, book he published in 1955.

Overview

In his own words, Bernays describes engineering consent as "use of an engineering approach—that is, action ...

(1947). He saw PR as an "applied social science" that uses insights from psychology, sociology, and other disciplines to scientifically manage and manipulate the thinking and behavior of an irrational and "herdlike" public.

In 1929, Edward Bernays helped the

In 1929, Edward Bernays helped the Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike is an American brand of cigarettes owned by the British American Tobacco group. Individual cigarettes of the brand are often referred to colloquially as "Luckies." Throughout their 150 year history, Lucky Strike has had fluctuating ...

cigarette brand increase its sales among the female demographic. Research showed that women were reluctant to carry a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes, because the brand's green color scheme clashed with popular fashion choices. Bernays persuaded fashion designers, charity events, interior designers and others to popularize the color green. He also positioned cigarettes as Torches of Freedom

"Torches of Freedom" was a phrase used to encourage women's smoking by exploiting women's aspirations for a better life during the early twentieth century first-wave feminism in the United States. Cigarettes were described as symbols of emancipati ...

that represent rebellion against the norms of a male-dominated society.

According to Ruth Edgett from Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

, Lee and Bernays both had "initial and spectacular successes in raising PR from the art of the snake oil salesman to the calling for a true communicator." However, "late in their careers, both Lee and Bernays took on clients with clearly reprehensible values, thus exposing themselves and their work to public criticism." Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

was also a contributor to early PR theory, for his work on the books ''Public Opinion'' (1922) and ''The Phantom Public'' (1925). He coined the term "manufacture of consent," which is based on the idea that the public's consent must be coaxed by experts to support a democratic society.

Former journalist Basil Clarke

Sir Thomas Basil Clarke (12 August 1879 – 12 December 1947) was an English war correspondent during the First World War and is regarded as the UK's first public relations professional.

Early life

Born in Altrincham, the son of a chemist, C ...

is considered the founder of PR in the UK. He founded the UK's first PR agency, Editorial Services, in 1924. He also authored the world's first code of ethics for the field in 1929. Clarke wrote that PR, "must look true and it must look complete and candid or its 'credit' is gone". He suggested that the selection of which facts are disseminated by PR campaigns could be used to persuade the public. The longest established UK PR agency is Richmond Towers, founded by Suzanne Richmond and Marjorie Towers in 1930.

Arthur W. Page Arthur Wilson Page (September 10, 1883 – September 5, 1960) was a vice president and director of AT&T from 1927 to 1947. He is sometimes referred to as "the father of corporate public relations" for his work at AT&T. The company was experiencing r ...

is sometimes considered to be the father of "corporate public relations" for his work with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile te ...

(AT&T) from 1927 to 1946. The company was experiencing resistance from the public to its monopolization efforts. In the early 1900s, AT&T had assessed that 90 percent of its press coverage was negative, which was reduced to 60 percent by changing its business practices and disseminating information to the press. According to business historian John Brooks, Page positioned the company as a public utility

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and r ...

and increased the public's appreciation for its contributions to society. On the other hand, Stuart Ewen writes that AT&T used its advertising dollars with newspapers to manipulate its coverage and had their PR team write feature stories imitating independent journalism

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independen ...

.

Early campaigns

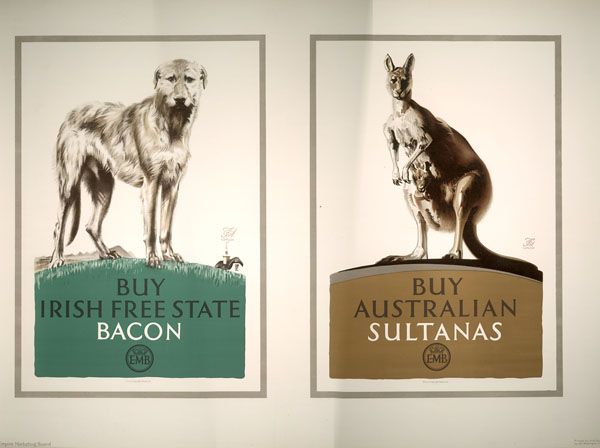

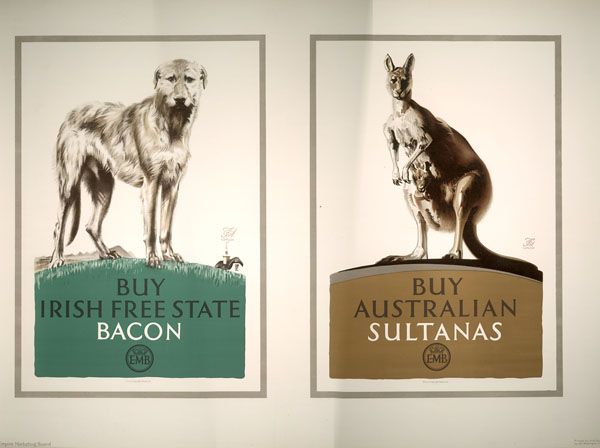

Edward Clarke and Bessie Tyler were influential in growing the

Edward Clarke and Bessie Tyler were influential in growing the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

to four million members over three years using publicity techniques in the early 1920s. In 1926 the Empire Marketing Board

The Empire Marketing Board was formed in May 1926 by the Colonial Secretary Leo Amery to promote intra-Empire trade and to persuade consumers to 'Buy Empire'. It was established as a substitute for tariff reform and protectionist legislation and ...

was formed by the British government in part to encourage a preference for goods produced in Britain. It folded in 1933 due to government cuts. In 1932, a pamphlet "''The Projection of England''" advocated for the importance of England managing its reputation domestically and abroad. The Ministry of Information was established in the UK in 1937.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

were the first Presidents to emphasize the use of publicity. In the 1930s Roosevelt used the media to promote The New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

and to blame corporations for the country's economic problems. This led companies to recruit their own publicists to defend themselves. Roosevelt's anti-trust efforts led corporations to attempt to persuade the public and lawmakers "that bigger orporationswas not necessarily more evil." Wilson used the media to promote his government reform program, The New Freedom. He formed the Committee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

.

In the 1930s, the National Association of Manufacturers

The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) is an advocacy group headquartered in Washington, D.C., with additional offices across the United States. It is the nation's largest manufacturing industrial trade association, representing 14,000 s ...

was one of the first to create a major campaign promoting capitalism and pro-business viewpoints. It lobbied against unions, The New Deal and the 8-hour work-day. NAM tried mostly unsuccessfully to convince the public that the interests of the public were aligned with corporate interests and to create an association between commerce and democratic principles. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Originally marketed as a temperance bar, temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, it was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pembe ...

promised that "every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents, wherever he is and whatever it costs the company." The company persuaded politicians that it was crucial to the war-effort and was exempted from sugar rationing. During the European Recovery Program

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

PR became more established in Europe as US-based companies with PR departments created European subsidiaries.

In 1938, amid concerns regarding dropping diamond prices and sales volume, De Beers

De Beers Group is an international corporation that specializes in diamond mining, diamond exploitation, diamond retail, diamond trading and industrial diamond manufacturing sectors. The company is active in open-pit, large-scale alluvial and ...

and its advertising agency N.W. Ayers adopted a strategy to "strengthen the association in the public's mind of diamonds with romance," whereas "the larger and finer the diamond, the greater the expression of love." This became known as one of America's "lexicon of great campaigns" for successfully persuading the public to purchase expensive luxury items during a time of financial stress through psychological manipulation

Manipulation in psychology is a behavior designed to exploit, control, or otherwise influence others to one’s advantage. Definitions for the term vary in which behavior is specifically included, influenced by both culture and whether referring t ...

. It also led to the development of the slogan "A diamond is forever" in 1947 and was influential in how diamonds were marketed thereafter. After World War I the first signs of public relations as a profession began in France and became more established through the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

.

Wartime propaganda

World War I

The first organized, large-scalepropaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

campaigns were during World War I. Germany created the German Information Bureau to create pamphlets, books and other communications that were intended to support the justness of their cause, to encourage voluntary recruitment, to demonize the enemy and persuade America to remain neutral in the conflict. In response to learning about Germany's propaganda, the British created a war propaganda agency called the Wellington House Wellington House is the more common name for Britain's War Propaganda Bureau, which operated during the First World War from Wellington House, a building on Buckingham Gate, London, which was the headquarters of the National Insurance Commission be ...

in September 1914. Atrocity stories, both real and alleged, were used to incite hatred for the enemy, especially after the "Rape of Belgium

The Rape of Belgium was a series of systematic war crimes, especially mass murder and deportation and enslavement, by German troops against Belgian civilians during the invasion and occupation of Belgium in World War I.

The neutrality ...

" in 1915. France created a propaganda agency in 1914. Publicity in Australia led to a lift in the government's ban on military drafts. Austria-Hungary used propaganda tactics to attack the credibility of Italy's leadership and its motives for war. Italy in-turn created the Padua Commission in 1918, which led Allied propaganda against Austria-Hungary.

One week after the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

established the US propaganda agency, the Committee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

(Creel Commission), as an alternative to demands for media censorship by the US army and navy. The CPI spread positive messages to present an upbeat image about the war and denied fraudulent atrocities made up to incite anger for the enemy. The CPI recruited about 75,000 "Four Minute Men

The Four Minute Men were a group of volunteers authorized by United States President Woodrow Wilson to give four-minute speeches on topics given to them by the Committee on Public Information (CPI). In 1917–1918, over 750,000 speeches were give ...

," volunteers who spoke about the war at social events for four minutes.

As a result of World War I propaganda, there was a shift in PR theory from a focus on factual argumentation to one of emotional appeals and the psychology of the crowd. The term "propaganda" which was originally associated with religion and the church, became a more widely known concept.

World War II

Propaganda did not develop a negative connotation until it was used inNazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

for World War II. Even though Germany's World War I propaganda was considered more advanced than that of other nations, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

said that propaganda had been under-utilized and claimed that superior British propaganda was the main reason for losing the war. Nazi Germany created the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (; RMVP), also known simply as the Ministry of Propaganda (), controlled the content of the press, literature, visual arts, film, theater, music and radio in Nazi Germany.

The ministry ...

in March 1933, just after Nazis took power. The Nazi party took editorial control over newspapers, created their own news organizations and established Nazi-controlled news organizations in conquered regions.Welch, 12. The Nazi party used posters, films, books and public speakers among other tactics.

According to historian Zbyněk Zeman

Zbyněk Anthony Bohuslav Zeman (18 October 1928 – 22 June 2011) was a Czech historian who later became a naturalized British citizen. He published widely on the history of Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th century. As an academic, he taugh ...

, broadcasting became the most important medium for propaganda throughout the war. Posters were also used domestically and leaflets were dropped behind enemy lines by air-ship. In regions conquered by Germany, citizens could be punished by death for listening to foreign broadcasts. Britain had four organizations involved in propaganda and was methodical about understanding its audiences in different countries. US propaganda focused on fighting for freedom and the connection between war efforts and industrial production. Soviet posters also focused on industrial production.

In countries where citizens are subordinate to the government, aggressive propaganda campaigns continued during peacetime, while liberal democratic nations primarily use propaganda techniques

A number of propaganda techniques based on social psychology, social psychological research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be classified as Informal fallacy, logical fallacies, since propagandists use arguments ...

to support war efforts.

Professional development

According to historian Eric Goldman, by the 1940s public relations was being taught at universities and was a professional occupation relied on in a similar way as lawyers and doctors. However, it failed to obtain complete recognition as a profession due in part to a history of deceit. Author Marvin Olasky said in 1987 that the reputation of the profession was getting worse, while Robert L. Heath from theUniversity of Houston

The University of Houston (UH) is a Public university, public research university in Houston, Texas. Founded in 1927, UH is a member of the University of Houston System and the List of universities in Texas by enrollment, university in Texas ...

said in 1991 that it was progressing toward "true professional status." Academic J. A. R. Pimlott said it had achieved "quasi-professionalism." Heath said despite the field's newfound professionalism and ethics, its reputation was still effected by a history of exploitive behavior.

The number of media outlets increased and PR talent from wartime propaganda entered the private sector. The practice of public relations became ubiquitous to reach political, activist and corporate objectives. The development of the press into a more real-time media also led to heightened scrutiny of public relations activities and those they represent. For example, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

was criticized for "doubletalk" and "stonewalling" in his PR office's responses to the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

.

Trade associations were formed first in the U.S. in 1947 with the Public Relations Society of America

The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) is a nonprofit trade association for public relations professionals. It was founded in 1947 by combining the American Council on Public Relations and the National Association of Public Relations C ...

(PRSA), followed by the Institute of Public Relations (now the Chartered Institute of Public Relations

The Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) is a professional body in the United Kingdom for public relations practitioners. Founded as the Institute for Public Relations in 1948, CIPR was awarded Chartered status by the Privy Council of ...

) in London in 1948. Similar trade associations were created in Australia, Europe, South Africa, Italy and Singapore. The International Association of Public Relations was founded in 1955. The Institute for Public Relations held its first conference in 1949 and that same year the first British book on PR, "Public Relations and publicity" was published by J.H. Brebner. The Foundation for Public Relations Research and Education (now thInstitute for Public Relations

was founded in 1956. The

International Association of Business Communicators

The International Association of Business Communicators (IABC) is a global network of communications professionals.

Each summer, IABC hosts a World Conference, a three-day event with professional development seminars and activities, as well as t ...

was founded in 1970. Betsy Ann Plank is called "the first lady of public relations" for becoming the first female president of the PRSA in 1973.

Two of today's largest PR firms, Edelman Edelman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Abram Wolf Edelman (a.k.a. Abraham Edelman; 1832–1907), Polish-born American rabbi; the first rabbi in Los Angeles, California

* Adam Edelman (born 1991), American-born four-time Is ...

and Burson-Marsteller

Burson Cohn & Wolfe is a multinational public relations and communications firm, headquartered in New York City. In February 2018, parent WPP Group PLC announced that it had merged its subsidiaries Cohn & Wolfe with Burson-Marsteller. The comb ...

, were founded in 1952 and 1953 respectively. Daniel Edelman

Daniel Joseph Edelman (July 3, 1920 – January 15, 2013) was an American public relations executive who founded the world's largest public relations firm, Edelman. Hevesi, Dennis (January 15, 2013)Daniel J. Edelman, a Publicity Pioneer, Dies a ...

created the first media tour in the 1950s by touring the country with "the Toni Twins," where one had used a professional salon and the other had used Toni's home-care products. It was also during this period that trade magazines like ''PR Week

''PRWeek'' is a trade magazine for the public relations industry. The original UK edition was the brainchild of the late Geoffrey Lace who at the time worked for Haymarket. After failing to interest Haymarket in his idea he left to launch it on ...

'', ''Ragans'' and ''PRNews'' were founded. John Hill, founder of Hill & Knowlton

Hill+Knowlton Strategies is an American global public relations consulting company, headquartered in New York City, United States, with over 80 offices in more than 40 countries. The company was founded in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1927 by John W. Hill ...

, is known as the first international PR pioneer. Hill & Knowlton was the first major U.S. firm to create a strong international network in the 1960s and 1970s. Both Edelman and Burson-Marsteller followed Hill & Knowlton by establishing operations in London in the 1960s and all three began competing internationally in Asia, Europe and other regions. Jacques Coup de Frejac was influential in persuading U.S. and UK companies to also extend their PR efforts into the French market and for convincing French businesses to engage in PR activities. In the early 2000s, PR in Latin America began developing at a pace "on par with industrialized nations."

According to ''The Global Public Relations Handbook'', public relations evolved from a series of "press agents or publicists" to a manner of theory and practice in the 1980s. Research was published in academic journals like ''Public Relations Review'' and the ''Journal of Public Relations Research''. This led to an industry consensus to categorize PR work into a four-step process: research, planning, communication and action.

Social and digital

During the 1990s specialties for communicating to certain audiences and within certain market segments emerged, such asinvestor relations

Investor relations (IR) is a strategic management responsibility that is capable of integrating finance, communication, marketing and securities law compliance to enable the most effective two-way communication between a company, the financial c ...

or technology PR. New internet technology and social media websites effected PR strategies and tactics. In April 1999, four managers from IBM, Sun Microsystems

Sun Microsystems, Inc. (Sun for short) was an American technology company that sold computers, computer components, software, and information technology services and created the Java programming language, the Solaris operating system, ZFS, t ...

, National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other n ...

and Linux Journal

''Linux Journal'' (''LJ'') is an American monthly technology magazine originally published by Specialized System Consultants, Inc. (SSC) in Seattle, Washington since 1994. In December 2006 the publisher changed to Belltown Media, Inc. in Houston, ...

created "The Cluetrain Manifesto

''The Cluetrain Manifesto'' is a work of business literature collaboratively authored by Rick Levine, Christopher Locke, Doc Searls, and David Weinberger. It was first posted to the web in 1999 as a set of ninety-five theses, and was published as ...

." The Manifesto established 95 theses about the way social media and internet technologies were going to change business. It concluded that markets had become "smarter and faster than most companies," because stakeholders were getting information from each other. The Manifesto "created a storm" with strong detractors and supporters. That same year, Seth Godin published a book on permission marketing

Permission marketing is a type of advertising in which the people who are supposed to see the ads can choose whether or not to get them. This marketing type is becoming quite popular in digital marketing these days. Seth Godin first introduced t ...

, which advocated against advertising and in favor of marketing that is useful and educational. While initially controversial, by 2006 it became commonly accepted that social media had an important role in public relations.

Press releases, which were mostly unchanged for more than a century, began to integrate digital features. BusinessWire

Business Wire is an American company that disseminates full-text press releases from thousands of companies and organizations worldwide to news media, financial markets, disclosure systems, investors, information web sites, databases, bloggers, ...

introduced the "Smart News Release," which incorporated audio, video and images, in 1997. This was followed by the MultiVu multimedia release from PRNewswire

PR Newswire is a distributor of press releases headquartered in Chicago. The service was created in 1954 to allow companies to electronically send press releases to news organizations, using teleprinters at first. The founder, Herbert Muschel, ...

in 2001. The Social Media Release was created by Todd Defren from Shift Communications

Shift may refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media Gaming

* ''Shift'' (series), a 2008 online video game series by Armor Games

* '' Need for Speed: Shift'', a 2009 racing video game

** '' Shift 2: Unleashed'', its 2011 sequel

Literature

* ''Sh ...

in 2006 in response to a blog written by journalist and blogger Tom Foremski titled "Die! Press release! Die! Die! Die!" Incorporating digital and social features became a norm among wire services, and companies started routinely making company announcements on their corporate blog.

According to ''The New York Times'', corporate communications shifted from a monologue to two-way conversational communications and new media also made it "easier for consumers to learn about the mix-ups and blunders" of PR. For example, after the ''Deepwater Horizon'' oil spill, BP tried to deflect blame to other parties, claim the spill was not as significant as it was and focused on the science, while human interest stories related to the damage were emerging. In 2011, Facebook tried to covertly spread privacy concerns about competitor Google's Social Circles. Chapstick

ChapStick is a brand name of lip balm manufactured by Haleon and used in many countries worldwide. It is intended to help treat and prevent chapped lips, hence the name. Many varieties also include sunscreen in order to prevent sunburn.

Due to ...

created a communications crisis after allegedly, repeatedly deleting negative comments on its Facebook page. During the Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

, it was exposed that the US created false radio personalities to spread pro-American information and paid Iraqi newspapers to write articles written by American troops.

See also

* History of advertising * History of advertising in BritainReferences

Further reading

* Cutlip, Scott ''The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History'' (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Taylor & Francis Group is an international company originating in England that publishes books and academic journals. Its parts include Taylor & Francis, Routledge, F1000 Research or Dovepress. It is a division of Informa plc, a United Ki ...

: 1994, 2nd ed. 2013) {{ISBN, 0-8058-1464-7.

* Cutlip, Scott M. "The unseen power: A brief history of public relations." in Clarke Caywood, ed. ''The handbook of strategic public relations and integrated communications'' (1997) pp: 15-33.

* online

* Watson, Tom. "The evolution of public relations measurement and evaluation." ''Public Relations Review'' 38#.3 (2012): 390-398

online

Public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

Public relations