History of penicillin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of penicillin follows a number of observations and discoveries of apparent evidence of antibiotic activity of the mould ''

The history of penicillin follows a number of observations and discoveries of apparent evidence of antibiotic activity of the mould ''

Fleming went off to resume his vacation and returned for the experiments late in September. He collected the original mould and grew them in culture plates. After four days he found that the plates developed large colonies of the mould. He repeated the experiment with the same bacteria-killing results. He later recounted his experience:

Fleming went off to resume his vacation and returned for the experiments late in September. He collected the original mould and grew them in culture plates. After four days he found that the plates developed large colonies of the mould. He repeated the experiment with the same bacteria-killing results. He later recounted his experience:

After structural comparison with different species of ''Penicillium'', Fleming initially believed that his specimen was ''

After structural comparison with different species of ''Penicillium'', Fleming initially believed that his specimen was ''

Fleming performed the first clinical trial with penicillin on Craddock. Craddock had developed severe infection of the

Fleming performed the first clinical trial with penicillin on Craddock. Craddock had developed severe infection of the

When production first began, one-liter containers had a yield of less than 1%, but improved to a yield of 80–90% in 10,000 gallon containers. This increase in efficiency happened between 1939 and 1945 as the result of continuous process innovation. Orvill May, the director of the

When production first began, one-liter containers had a yield of less than 1%, but improved to a yield of 80–90% in 10,000 gallon containers. This increase in efficiency happened between 1939 and 1945 as the result of continuous process innovation. Orvill May, the director of the

Debate in the House of Commons

on the history and the future of the discovery.

The history of penicillin follows a number of observations and discoveries of apparent evidence of antibiotic activity of the mould ''

The history of penicillin follows a number of observations and discoveries of apparent evidence of antibiotic activity of the mould ''Penicillium

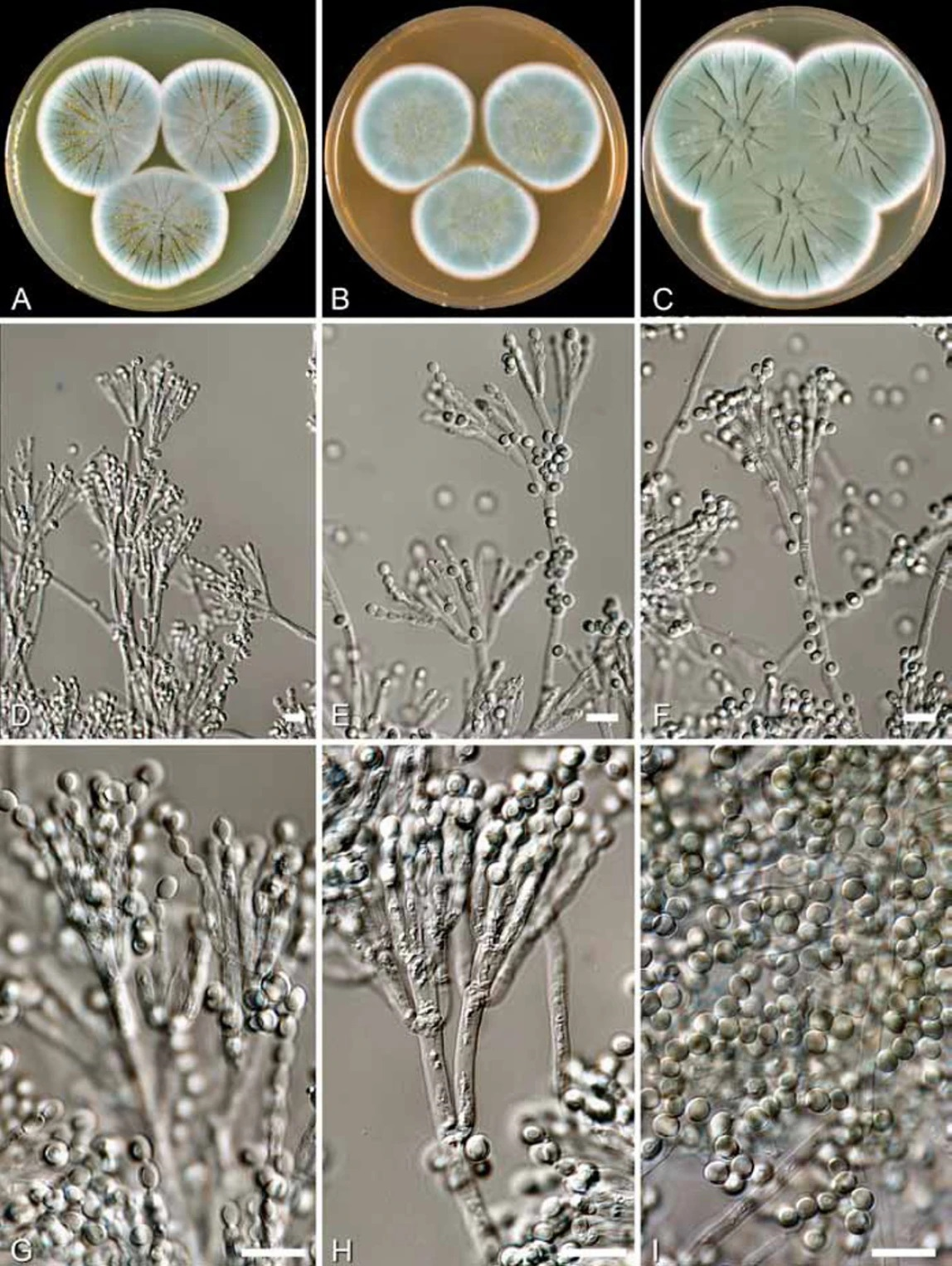

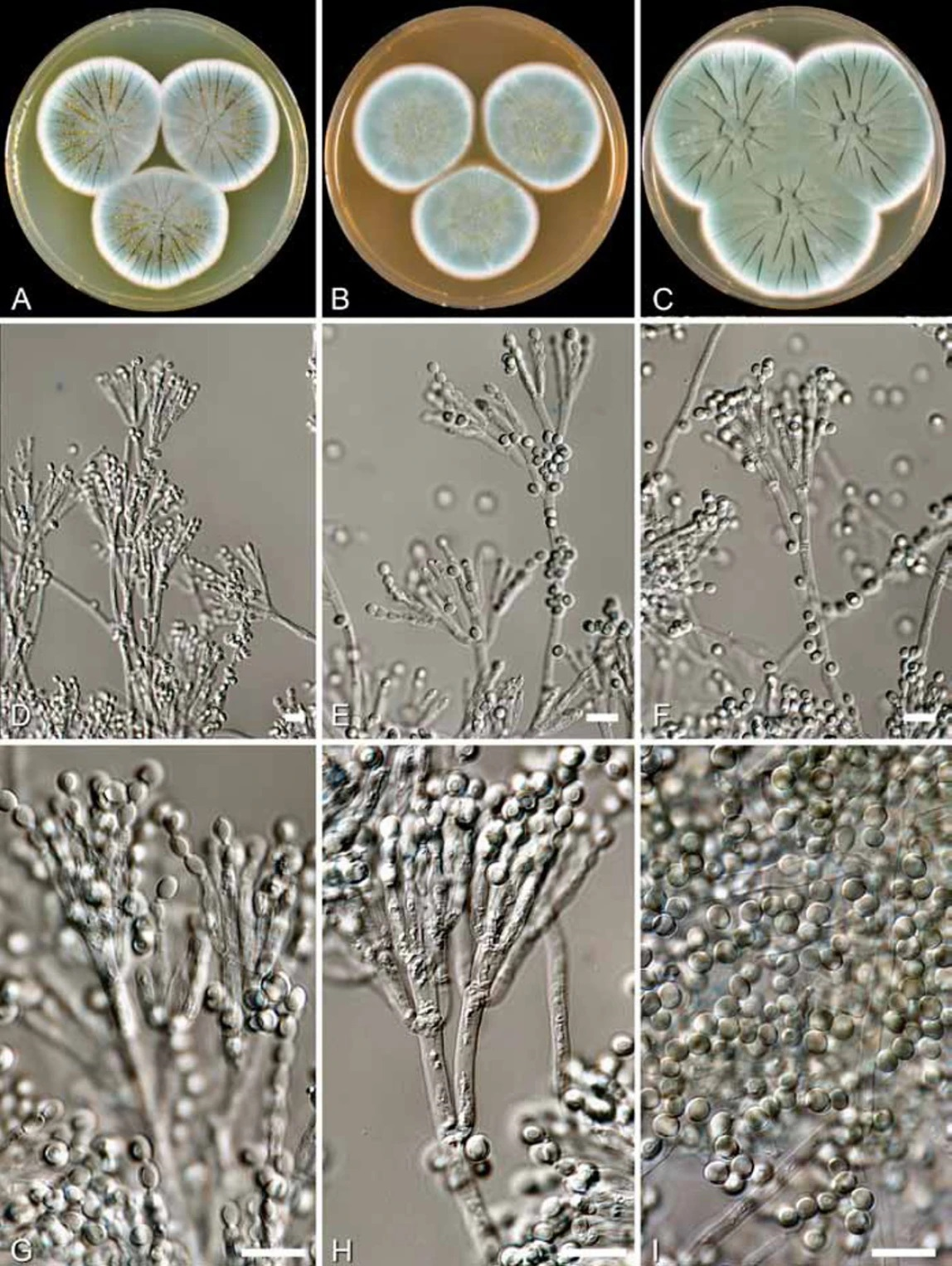

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of ascomycetous fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of the genus produce pe ...

'' that led to the development of penicillins

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

that became the most widely used antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and preventio ...

. Following the identification of ''Penicillium rubens

''Penicillium rubens'' is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium'' and was the first species known to produce the antibiotic penicillin. It was first described by Philibert Melchior Joseph Ehi Biourge in 1923. For the discovery of penici ...

'' as the source of the compound in 1928 and with the production of pure compound in 1942, penicillin became the first naturally derived antibiotic. There are anecdotes about ancient societies using moulds to treat infections, and in the following centuries many people observed the inhibition of bacterial growth by various moulds. However, it is unknown if the species involved were ''Penicillium

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of ascomycetous fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of the genus produce pe ...

'' species or if the antimicrobial substances produced were penicillin.

While working at St Mary's Hospital in London, Scottish physician Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of what ...

was the first to experimentally discover that a ''Penicillium'' mould secretes an antibacterial substance, and the first to concentrate the active substance involved, which he named penicillin in 1928. The mould was determined to be a rare variant of ''Penicillium notatum

''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (formerly known as ''Penicillium notatum'') is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium''. It is common in temperate and subtropical regions and can be found on salted food products, but it is mostly found in in ...

'' (now ''Penicillium rubens

''Penicillium rubens'' is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium'' and was the first species known to produce the antibiotic penicillin. It was first described by Philibert Melchior Joseph Ehi Biourge in 1923. For the discovery of penici ...

''), a laboratory contaminant in his lab. For the next 16 years, he pursued better methods of production of penicillin, medicinal uses and clinical trial. His successful treatment of Harry Lambert who had otherwise fatal streptococcal meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

in 1942 proved to be a critical moment in the medical usage of penicillin.

Many later scientists were involved in the stabilization and mass production of penicillin and in the search for more productive strains of ''Penicillium''. Important contributors include Ernst Chain

Sir Ernst Boris Chain (19 June 1906 – 12 August 1979) was a German-born British biochemist best known for being a co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on penicillin.

Life and career

Chain was born in B ...

, Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role ...

, Norman Heatley

Norman George Heatley OBE (10 January 1911 – 5 January 2004) was an English biologist and biochemist. He was a member of the team of Oxford University scientists who developed penicillin. Norman Heatley developed the back-extraction technique ...

and Edward Abraham

Sir Edward Penley Abraham, (10 June 1913 – 8 May 1999) was an English biochemist instrumental in the development of the first antibiotics penicillin and cephalosporin.

Early life and education

Abraham was born on 10 June 1913 at 47 South ...

. Fleming, Florey and Chain shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

for the discovery and development of penicillin. Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin received the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

determining the structures of important biochemical substances including penicillin. Shortly after the discovery of penicillin, there were reports of penicillin resistance in many bacteria. Research that aims to circumvent and understand the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

continues today.

Early history

Many ancient cultures, including those inEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, independently discovered the useful properties of fungi and plants in treating infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

. These treatments often worked because many organisms, including many species of mould, naturally produce antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

substances. However, ancient practitioners could not precisely identify or isolate the active components in these organisms.

In 17th-century Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, wet bread was mixed with spider webs (which often contained fungal spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, ...

s) to treat wounds. The technique was mentioned by Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish writer, novelist, journalist and Nobel Prize laureate. He is best remembered for his historical novels, espe ...

in his 1884 book ''With Fire and Sword

''With Fire and Sword'' ( pl, Ogniem i mieczem, links=no) is a historical novel by the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz, published in 1884. It is the first volume of a series known to Poles as The Trilogy, followed by '' The Deluge'' (''Potop'' ...

''. In England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

in 1640, the idea of using mould as a form of medical treatment was recorded by apothecaries such as John Parkinson, King's Herbarian, who advocated the use of mould in his book on pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

.

Early scientific evidence

The modern history of penicillin research begins in earnest in the 1870s in the United Kingdom. Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson, who started out at St. Mary's Hospital (1852–1858) and later worked there as a lecturer (1854–1862), observed thatculture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

fluid covered with mould would produce no bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

l growth. Burdon-Sanderson's discovery prompted Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

, an English surgeon and the father of modern antisepsis

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/ skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or pu ...

, to discover in 1871 that urine samples contaminated with mould also did not permit the growth of bacteria. Lister also described the antibacterial action on human tissue of a species of mould he called '' Penicillium glaucum''. A nurse at King's College Hospital

King's College Hospital is a major teaching hospital and major trauma centre in Denmark Hill, Camberwell in the London Borough of Lambeth, referred to locally and by staff simply as "King's" or abbreviated internally to "KCH". It is managed b ...

whose wounds did not respond to any traditional antiseptic was then given another substance that cured him, and Lister's registrar informed him that it was called ''Penicillium''. In 1874, the Welsh physician William Roberts, who later coined the term "enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

", observed that bacterial contamination is generally absent in laboratory cultures of ''Penicillium glaucum''. John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was a prominent 19th-century Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the ...

followed up on Burdon-Sanderson's work and demonstrated to the Royal Society in 1875 the antibacterial action of the ''Penicillium'' fungus.

In 1876, German biologist Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the bacteri ...

discovered that ''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent ( obligate) pathogen within the genus '' Bacillus''. Its infection is a ...

'' was the causative pathogen of anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The s ...

, which became the first demonstration that a specific bacterium caused a specific disease, and the first direct evidence of germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade ...

s. In 1877, French biologists Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

and Jules Francois Joubert observed that cultures of the anthrax bacilli, when contaminated with moulds, could be successfully inhibited. Reporting in the ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences'', they concluded:Neutral or slightly alkaline urine is an excellent medium for the bacteria... But if when the urine is inoculated with these bacteria an aerobic organism, for example one of the "common bacteria," is sown at the same time, the anthrax bacterium makes little or no growth and sooner or later dies out altogether. It is a remarkable thing that the same phenomenon is seen in the body even of those animals most susceptible to anthrax, leading to the astonishing result that anthrax bacteria can be introduced in profusion into an animal, which yet does not develop the disease; it is only necessary to add some "common 'bacteria" at the same time to the liquid containing the suspension of anthrax bacteria. These facts perhaps justify the highest hopes for therapeutics.The phenomenon was described by Pasteur and Koch as antibacterial activity and was named as "antibiosis" by French biologist

Jean Paul Vuillemin

Jean Paul Vuillemin (13 February 1861 – 25 September 1932 in Malzéville) was a French mycologist born in Docelles.

He studied at the University of Nancy, earning his medical doctorate in 1884. In 1892 he obtained his doctorate in sciences at ...

in 1877. (The term antibiosis, meaning "against life", was adopted as "antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

" by American biologist and later Nobel laureate Selman Waksman

Selman Abraham Waksman (July 22, 1888 – August 16, 1973) was a Jewish Russian-born American inventor, Nobel Prize laureate, biochemist and microbiologist whose research into the decomposition of organisms that live in soil enabled the discover ...

in 1947.) It has also been asserted that Pasteur identified the strain as ''Penicillium notatum

''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (formerly known as ''Penicillium notatum'') is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium''. It is common in temperate and subtropical regions and can be found on salted food products, but it is mostly found in in ...

''. However, Paul de Kruif's 1926 ''Microbe Hunters'' describes this incident as contamination by other bacteria rather than by mould. In 1887, Swiss physician Carl Alois Philipp Garré developed a test method using glass plate to see bacterial inhibition and found similar results. Using his gelatin-based culture plate, he grew two different bacteria and found that their growths were inhibited differently, as he reported:I inoculated on the untouched cooled elatinplate alternate parallel strokes of ''B. fluorescens'' 'Pseudomonas_fluorescens''.html" ;"title="Pseudomonas_fluorescens.html" ;"title="'Pseudomonas fluorescens">'Pseudomonas fluorescens''">Pseudomonas_fluorescens.html" ;"title="'Pseudomonas fluorescens">'Pseudomonas fluorescens''and ''Staph. pyogenes'' [''Streptococcus pyogenes'' ]... B. fluorescens grew more quickly... [This] is not a question of overgrowth or crowding out of one by another quicker-growing species, as in a garden where luxuriantly growing weeds kill the delicate plants. Nor is it due to the utilization of the available foodstuff by the more quickly growing organisms, rather there is an antagonism caused by the secretion of specific, easily diffusible substances which are inhibitory to the growth of some species but completely ineffective against others.In 1895,

Vincenzo Tiberio

Vincenzo Tiberio (May 1, 1869 – January 7, 1915) was an Italian researcher and medical officer of the Medical Corps of the Italian Navy and physician at the University of Naples. Observing that people complained of intestinal disorders after the ...

, an Italian physician at the University of Naples

The University of Naples Federico II ( it, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II) is a public university in Naples, Italy. Founded in 1224, it is the oldest public non-sectarian university in the world, and is now organized into 26 depar ...

, published research about moulds initially found in a water well in Arzano

Arzano is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Naples in the Italian region Campania, located about 9 km north of Naples.

Arzano borders the following municipalities: Casandrino, Casavatore, Casoria, Frattamaggiore, ...

; from his observations, he concluded that these moulds contained soluble substances having antibacterial action.

Two years later, Ernest Duchesne at École du Service de Santé Militaire in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

independently discovered the healing properties of a ''Penicillium glaucum'' mould, even curing infected guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus '' Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ...

s of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

. He published a dissertation in 1897 but it was ignored by the Institut Pasteur

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccine ...

. Duchesne was himself using a discovery made earlier by Arab stable boys, who used moulds to cure sores on horses. He did not claim that the mould contained any antibacterial substance, only that the mould somehow protected the animals. The penicillin isolated by Fleming does not cure typhoid and so it remains unknown which substance might have been responsible for Duchesne's cure. An Institut Pasteur scientist, Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

n Clodomiro Picado Twight

Clodomiro Picado Twight (April 17, 1887 - May 16, 1944), also known as "Clorito Picado", was a Costa Rican scientist who was internationally recognized for his pioneering research on snake venom and the development of various antivenins. His wor ...

, similarly recorded the antibiotic effect of ''Penicillium'' in 1923. In these early stages of penicillin research, most species of ''Penicillium

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of ascomycetous fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of the genus produce pe ...

'' were non-specifically referred to as ''Penicillium glaucum'', so that it is impossible to know the exact species and that it was really penicillin that prevented bacterial growth.

Andre Gratia and Sara Dath at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium, were studying the effects of mould samples on bacteria. In 1924, they found that dead ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posit ...

'' cultures were contaminated by a mould, a streptomycete

The ''Streptomycetaceae'' are a family of ''Actinomycetota'', making up the monotypic order ''Streptomycetales''. It includes the important genus ''Streptomyces''. This was the original source of many antibiotics, namely streptomycin, the first ...

. Upon further experimentation, they shows that the mould extract could kill not only ''S. aureus'', but also ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated, gram-negative, aerobic– facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that can cause disease in plants and animals, including humans. A species of considerable medical importance, ''P. a ...

'', ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on it ...

'' and ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Esc ...

''. Gratia called the antibacterial agent as "mycolysate" (killer mould). The next year they found another killer mould that could inhibit anthrax bacterium (''B. anthracis''). Reporting in ''Comptes Rendus Des Séances de La Société de Biologie et de Ses Filiales'' they identified the mould as ''Penicillium glaucum''. But these findings received little attention as the antibacterial agent and its medical value were not fully understood; moreover, Gratia's samples were lost.

The breakthrough discovery

Background

Penicillin was discovered by a Scottish physicianAlexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of what ...

in 1928. While working at St Mary's Hospital, London

St Mary's Hospital is an NHS hospital in Paddington, in the City of Westminster, London, founded in 1845. Since the UK's first academic health science centre was created in 2008, it has been operated by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Tru ...

, Fleming was investigating the pattern of variation in ''S. aureus''. He was inspired by the discovery of an Irish physician Joseph Warwick Bigger and his two students C.R. Boland and R.A.Q. O’Meara at the Trinity College, Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

, Ireland, in 1927''.'' Bigger and his students found that when they cultured a particular strain of ''S. aureus,'' which they designated "Y" that they isolated a year before from a pus of axillary abscess from one individual, the bacterium grew into a variety of strains. They published their discovery as “Variant colonies of ''Staphylococcus aureus''” in '' The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology,'' by concluding:

We were surprised and rather disturbed to find, on a number of plates, various types of colonies which differed completely from the typical ''aureus'' colony. Some of these were quite white; some, either white or of the usual colour were rough on the surface and with crenated margins.Fleming and his research scholar Daniel Merlin Pryce pursued this experiment but Pryce was transferred to another laboratory in early 1928. After a few months of working alone, a new scholar Stuart Craddock joined Fleming. Their experiment was successful and Fleming was planning and agreed to write a report in ''A System of Bacteriology'' to be published by the Medical Research Council by the end of 1928.

Initial discovery

In August, Fleming spent a vacation with his family at his country home The Dhoon atBarton Mills

Barton Mills is a village and civil parish in the West Suffolk district of Suffolk, England. The village is on the south bank of the River Lark. According to Eilert Ekwall the meaning of the village name is 'corn farm by the mill'.

The village ...

, Suffolk. Before leaving his laboratory, he inoculated several culture plates with ''S. aureus.'' He kept the plates aside on one corner of the table away from direct sunlight and to make space for Craddock to work in his absence. While in a vacation, he was appointed Professor of Bacteriology at the St Mary's Hospital Medical School on 1 September 1928. He arrived at his laboratory on 3 September, where Pryce was waiting to greet him. As he and Pryce examined the culture plates, they found one with an open lid and the culture contaminated with a blue-green mould. In the contaminated plate the bacteria around the mould did not grow, while those farther away grew normally, meaning that the mould killed the bacteria. Fleming commented as he watched the plate: "That's funny". Pryce remarked to Fleming: "That's how you discovered lysozyme

Lysozyme (EC 3.2.1.17, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycoside ...

."

Experiment

When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.He concluded that the mould was releasing a substance that was inhibiting bacterial growth, and he produced culture broth of the mould and subsequently concentrated the antibacterial component. After testing against different bacteria, he found that the mould could kill only specific bacteria. For example, ''Staphylococcus'', ''

Streptococcus

''Streptococcus'' is a genus of gram-positive ' (plural ) or spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs ...

'', and diphtheria bacillus (''Corynebacterium diphtheriae

''Corynebacterium diphtheriae'' is the pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. It is also known as the Klebs–Löffler bacillus, because it was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs (1834–1912) and Friedrich Löff ...

'') were easily killed; but there was no effect on typhoid bacterium (''Salmonella typhimurium

''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' is a subspecies of ''Salmonella enterica'', the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the ''S. enterica'' species are in this subspecies, includin ...

'') and influenza bacillus (''Haemophilus influenzae''). He prepared large-culture method from which he could obtain large amounts of the mould juice. He called this juice "penicillin", as he explained the reason as "to avoid the repetition of the rather cumbersome phrase 'Mould broth filtrate,' the name 'penicillin' will be used."; Reprinted as He invented the name on 7 March 1929. He later (in his Nobel lecture) gave a further explanation, saying:

I have been frequently asked why I invented the name "Penicillin". I simply followed perfectly orthodox lines and coined a word which explained that the substance penicillin was derived from a plant of the genus ''Penicillium'' just as many years ago the word "Fleming had no training in chemistry so that he left all the chemical works to Craddock – he once remarked, "I am a bacteriologist, not a chemist." In January 1929, he recruited Frederick Ridley, his former research scholar who had studied biochemistry, specifically to the study the chemical properties of the mould. But they could not isolate penicillin and before the experiments were over, Craddock and Ridley both left Fleming for other jobs. It was due to their failure to isolate the compound that Fleming practically abandoned further research on the chemical aspects of penicillin, although he did biological tests up to 1939.Digitalin Digoxin (better known as Digitalis), sold under the brand name Lanoxin among others, is a medication used to treat various heart conditions. Most frequently it is used for atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and heart failure. Digoxin is o ..." was invented for a substance derived from the plant ''Digitalis''.

Identification of the mould

After structural comparison with different species of ''Penicillium'', Fleming initially believed that his specimen was ''

After structural comparison with different species of ''Penicillium'', Fleming initially believed that his specimen was ''Penicillium chrysogenum

''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (formerly known as ''Penicillium notatum'') is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium''. It is common in temperate and subtropical regions and can be found on salted food products, but it is mostly found in in ...

,'' a species described by an American microbiologist Charles Thom

Charles Thom (November 11, 1872 – May 24, 1956) was an American microbiologist and mycology, mycologist. Born and raised in Illinois, he received his PhD from the University of Missouri, the first such degree awarded by that institution. He w ...

in 1910. He was fortunate as Charles John Patrick La Touche, an Irish botanist, had just recently joined as a mycologist

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungi, including their genetic and biochemical properties, their taxonomy and their use to humans, including as a source for tinder, traditional medicine, food, and entheogens, as ...

at St Mary's to investigate fungi as the cause of asthma. La Touche identified the specimen as ''Penicillium rubrum,'' the identification used by Fleming in his publication.

In 1931, Thom re-examined different ''Penicillium'' including that of Fleming's specimen. He came to a confusing conclusion, stating, "Ad. 35 leming's specimenis ''P. notatum'' WESTLING. This is a member of the ''P. chrysogenum'' series with smaller conidia than ''P. chrysogenum'' itself." ''P. notatum'' was described by Swedish chemist Richard Westling in 1811. From then on, Fleming's mould was synonymously referred to as ''P. notatum'' and ''P. chrysogenum.'' But Thom adopted and popularised the use of ''P. chrysogenum.'' In addition to ''P. notatum'', newly discovered species such as ''P. meleagrinum'' and ''P. cyaneofulvum'' were recognised as members of ''P. chrysogenum'' in 1977''.'' To resolve the confusion, the Seventeenth International Botanical Congress

International Botanical Congress (IBC) is an international meeting of botanists in all scientific fields, authorized by the International Association of Botanical and Mycological Societies (IABMS) and held every six years, with the location rotati ...

held in Vienna, Austria, in 2005 formally adopted the name ''P. chrysogenum'' as the conserved name (''nomen conservandum

Nomen may refer to:

* Nomen (Roman name), the middle part of Ancient Roman names

* Nomen (Ancient Egypt), the personal name of Ancient Egyptian pharaohs

* Jaume Nomen (born 1960), Catalan astronomer

*Nomen, Latin for a certain part of speech

*Nom ...

).'' Whole genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis in 2011 revealed that Fleming's mould belongs to '' P. rubens,'' a species described by Belgian microbiologist Philibert Biourge in 1923, and also that ''P. chrysogenum'' is a different species.

The source of the fungal contamination in Fleming's experiment remained a speculation for several decades. Fleming himself suggested in 1945 that the fungal spores came through the window facing Praed Street. This story was regarded as a fact and was popularised in literature, starting with George Lacken's 1945 book ''The Story of Penicillin''. But it was later disputed by his co-workers including Pryce, who testified much later that Fleming's laboratory window was kept shut all the time. Ronald Hare also agreed in 1970 that the window was most often locked because it was difficult to reach due to a large table with apparatuses placed in front of it. In 1966, La Touche told Hare that he had given Fleming 13 specimens of fungi (10 from his lab) and only one from his lab was showing penicillin-like antibacterial activity. It was from this point a consensus was made that Fleming's mould came from La Touche's lab, which was a floor below in the building, the spores being drifted in the air through the open doors.

Reception and publication

Fleming's discovery was not regarded initially as an important discovery. Even as he showed his culture plates to his colleagues, all he received was an indifferent response. He described the discovery on 13 February 1929 before the Medical Research Club. His presentation titled "A medium for the isolation of Pfeiffer's bacillus" did not receive any particular attention. In 1929, Fleming reported his findings to the ''British Journal of Experimental Pathology'' on 10 May 1929, and was published in the next month issue.; Reprint of It failed to attract any serious attention. Fleming himself was quite unsure of the medical application and was more concerned on the application for bacterial isolation, as he concluded:In addition to its possible use in the treatment of bacterial infections penicillin is certainly useful to the bacteriologist for its power of inhibiting unwanted microbes in bacterial cultures so that penicillin insensitive bacteria can readily be isolated. A notable instance of this is the very easy, isolation of Pfeiffers bacillus of influenza when penicillin is used...It is suggested that it may be an efficient antiseptic for application to, or injection into, areas infected with penicillin-sensitive microbes.G. E. Breen, a fellow member of the

Chelsea Arts Club

The Chelsea Arts Club is a private members' club at 143 Old Church Street in Chelsea, London with a membership of over 3,800, including artists, sculptors, architects, writers, designers, actors, musicians, photographers, and filmmakers. The club ...

, once asked Fleming, "I just wanted you to tell me whether you think it will ever be possible to make practical use of the stuff enicillin For instance, could I use it?" Fleming gazed vacantly for a moment and then replied, "I don't know. It's too unstable. It will have to be purified, and I can't do that by myself." Even as late as in 1941, the ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origi ...

'' reported that "the main facts emerging from a very comprehensive study f penicillinin which a large team of workers is engaged... does not appear to have been considered as possibly useful from any other point of view."

Isolation

In 1939,Ernst Boris Chain

Sir Ernst Boris Chain (19 June 1906 – 12 August 1979) was a German-born British biochemist best known for being a co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on penicillin.

Life and career

Chain was born in Ber ...

, a German (later naturalised British) chemist, joined the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

to investigate on antibiotics. He was immediately impressed by Fleming's 1929 paper, and informed his supervisor, the Australian scientist Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role ...

(later Baron Florey), of the potential drug. By then Florey had acquired a research grant of $25,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation for studying antibiotics. He assembled a research team including Mary Ethel Florey

Mary Ethel Florey (née Hayter Reed), Baroness Florey (1 October 1900 – 10 October 1966) was an Australian doctor and medical scientist. Her work was instrumental in the discovery of penicillin. She was part of the team that ran the first trials ...

, Edward Abraham

Sir Edward Penley Abraham, (10 June 1913 – 8 May 1999) was an English biochemist instrumental in the development of the first antibiotics penicillin and cephalosporin.

Early life and education

Abraham was born on 10 June 1913 at 47 South ...

, Arthur Duncan Gardner

He was born on 28 March 1884 and educated at Rugby School, before entering University College, University of Oxford to study Law. Upon completing his degree, he rejected the family law practice to study Medicine. After qualifying in 1911 and obta ...

, Norman Heatley

Norman George Heatley OBE (10 January 1911 – 5 January 2004) was an English biologist and biochemist. He was a member of the team of Oxford University scientists who developed penicillin. Norman Heatley developed the back-extraction technique ...

, Margaret Jennings, J. Orr-Ewing and G. Sanders in addition to Chain.

The Oxford team prepared a concentrated extract of ''P. rubens'' as "a brown powder" that "has been obtained which is freely soluble in water". They found that the powder was not only effective ''in vitro'' against bacterial cultures but also and ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and p ...

'' against bacterial infection in mice. On 5 May 1939, they injected a group of eight mice with a virulent strain of ''S. aureus'', and then injected four of them with the penicillin solution. After one day, all the untreated mice died while the penicillin-treated mice survived. Chain remarked it as "a miracle." They published their findings in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles ...

'' in 1940.

The team reported details of the isolation method in 1941 with a scheme for large-scale extraction. They also found that penicillin was most abundant as yellow concentrate from the mould extract. But they were able to produce only small quantities. By early 1942, they could prepare highly purified compound, and worked out the chemical formula as C24H32O10N2Ba. In mid-1942, Chain, Abraham and E. R. Holiday reported the production of the pure compound.

First medical use

nasal antrum

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal c ...

(sinusitis

Sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis, is inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the sinuses resulting in symptoms that may include thick nasal mucus, a plugged nose, and facial pain. Other signs and symptoms may include fever, head ...

) and had undergone surgery. Fleming made use of the surgical opening of the nasal passage and started injecting penicillin on 9 January 1929 but without any effect. It probably was due to the fact that the infection was with influenza bacillus (''Haemophilus influenzae''), the bacterium which he had found unsusceptible to penicillin. Fleming gave some of his original penicillin samples to his colleague-surgeon Arthur Dickson Wright for clinical test in 1928. Although Wright reportedly said that it "seemed to work satisfactorily," there are no records of its specific use.

Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire ...

, was the first to successfully use penicillin for medical treatment. He was a former student of Fleming and when he learned of the discovery, asked the penicillin sample from Fleming. He initially attempted to treat sycosis

Sycosis is an inflammation of hair follicles, especially of the beard area,thefreedictionary.com > sycosisciting: Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. 2007thefreedictionary.com > sycosisciting: The American Heritage® Medical Diction ...

(eruptions in beard follicles) with penicillin but was unsuccessful, probably because the drug did not penetrate deep enough. Moving on to ophthalmia neonatorum

Ophthalmia (also called ophthalmitis) is inflammation of the eye. It results in congestion of the eyeball, often eye-watering, redness and swelling, itching and burning, and a general feeling of irritation under the eyelids. Ophthalmia can have d ...

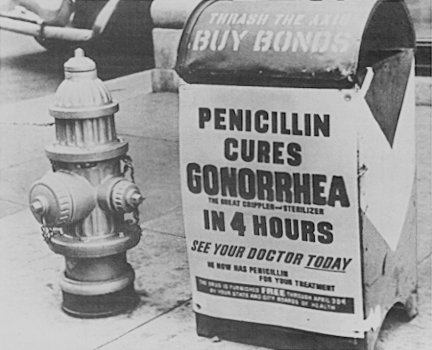

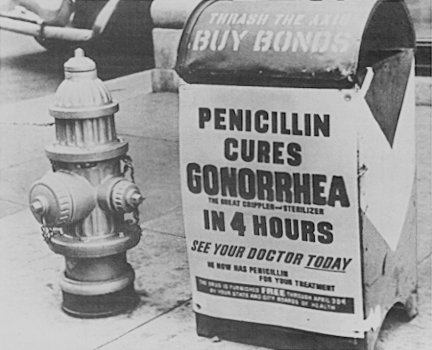

, a gonococcal infection in babies, he achieved the first cure on 25 November 1930, four patients (one adult, the others infants) with eye infections.

Florey's team at Oxford showed that ''Penicillium'' extract killed different bacteria (''Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus,'' and ''Clostridium septique'') in culture and effectively cured ''Streptococcus'' infection in mice. They reported in the 24 August 1940 issue of ''The Lancet'' as "Penicillin as a chemotherapeutic agent" with a conclusion:

The results are clear cut, and show that penicillin is active in vivo against at least three of the organisms inhibited in vitro. It would seem a reasonable hope that all organisms in high dilution in vitro will be found to be dealt with in vivo. Penicillin does not appear to be related to any chemotherapeutic substance at present in use and is particularly remarkable for its activity against the anaerobic organisms associated withIn 1941, the Oxford team treated a policeman, Albert Alexander, with a severe face infection; his condition improved, but then supplies of penicillin ran out and he died. Subsequently, several other patients were treated successfully. In December 1942, survivors of thegas gangrene Gas gangrene (also known as clostridial myonecrosis and myonecrosis) is a bacterial infection that produces tissue gas in gangrene. This deadly form of gangrene usually is caused by '' Clostridium perfringens'' bacteria. About 1,000 cases of gas ....

Cocoanut Grove fire

The Cocoanut Grove fire was a nightclub fire which took place in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, on November 28, 1942, and resulted in the deaths of 492 people. It is the deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history, and the second-deadliest ...

in Boston were the first burn patients to be successfully treated with penicillin.

The most important clinical test was in August 1942 when Fleming cured Harry Lambert of an otherwise-fatal infection of the nervous system (streptococcal meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

). Lambert was a work associate of Robert, Fleming's brother, who had requested Fleming for medical treatment. Fleming asked Florey for the purified penicillin sample, which Fleming immediately used to inject into Lambert's spinal canal. Lambert showed signs of improvement the very next day, and completely recovered within a week. Fleming reported his clinical trial in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles ...

'' in 1943. It was upon this medical evidence that the British War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

set up the Penicillin Committee on 5 April 1943. The committee consisted of Cecil Weir, Director General of Equipment, as Chairman, Fleming, Florey, Sir Percival Hartley, Allison and representatives from pharmaceutical companies as members. This led to mass production of penicillin by the next year.

Mass production

Knowing that large-scale production for medical use was futile in a confined laboratory, the Oxford team tried to convince war-torn British government and private companies for mass production but in vain. Florey and Heatley travelled to the US in June 1941 to persuade US government and pharmaceutical companies there. Knowing that keeping the mould sample in vials could be easily lost, they instead smeared their coat pockets with the mould. They arrived in Washington D.C. in early July to discuss with Ross Granville Harrison, chairman of the National Research Council (NRC), and Charles Thom and Percy Wells of theUnited States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

. They were directed to approach the USDA

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL, now the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research) where large-scale fermentations were done. They reached Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria Metropolitan Area in Ce ...

, on 14 July to meet Andrew Jackson Moyer and Robert D. Coghill at the NRRL. The Americans quickly worked on the mould and were able to make culture by the end of July. But they realised that Fleming's mould was not efficient enough to produce large quantities of penicillin.

NRRL mycologist Kenneth Bryan Raper got the help of US Army Transport Command to search for similar mould in different parts of the world and the best moulds were found to be those from Chungkin (China), Bombay (Mumbai, India) and Cape Town (South Africa). But the single-best sample was from cantaloupe

The cantaloupe, rockmelon (Australia and New Zealand, although cantaloupe is used in some states of Australia), sweet melon, or spanspek (Southern Africa) is a melon that is a variety of the muskmelon species (''Cucumis melo'') from the fami ...

(a type of melon) sold in a Peoria fruit market in 1943. The mould was identified as ''P. chrysogenum'' and designated as NRRL 1951 or cantaloupe strain. There is a popular story that Mary K. Hunt (or Mary Hunt Stevens), a staff member of Raper, collected the mould; for which she had been popularised as "Mouldy Mary." But Raper remarked this story as a "folklore" and that the fruit was delivered to the lab by a woman from the Peoria fruit market.

Between 1941 and 1943, Moyer, Coghill and Kenneth Raper developed methods for industrialized penicillin production and isolated higher-yielding strains of the ''Penicillium'' fungus. Simultaneous research by Jasper H. Kane

Jasper Herbert Kane (July 15, 1903 – November 23, 2004) was an American biochemist who had a central role in moving antibiotics such as penicillin from the laboratory table into industrial production in World War II. He was an alumnus of what is ...

and other Pfizer

Pfizer Inc. ( ) is an American multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporation headquartered on 42nd Street in Manhattan, New York City. The company was established in 1849 in New York by two German entrepreneurs, Charles Pfize ...

scientists in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

developed the practical, deep-tank fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

method for production of large quantities of pharmaceutical-grade penicillin.  When production first began, one-liter containers had a yield of less than 1%, but improved to a yield of 80–90% in 10,000 gallon containers. This increase in efficiency happened between 1939 and 1945 as the result of continuous process innovation. Orvill May, the director of the

When production first began, one-liter containers had a yield of less than 1%, but improved to a yield of 80–90% in 10,000 gallon containers. This increase in efficiency happened between 1939 and 1945 as the result of continuous process innovation. Orvill May, the director of the Agricultural Research Service

The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is the principal in-house research agency of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). ARS is one of four agencies in USDA's Research, Education and Economics mission area. ARS is charged with ext ...

, had Robert Coghill, who was the chief of the fermentation division, use his experience with fermentation to increase the efficiency of extracting penicillin from the mould. Shortly after beginning, Moyer replaced sucrose with lactose in the growth media, which resulted in an increased yield. An even larger increase occurred when Moyer added corn steep liquor Corn steep liquor is a by-product of corn wet-milling. A viscous concentrate of corn solubles which contains amino acids, vitamins and minerals, it is an important constituent of some growth media. It was used in the culturing of ''Penicillium'' du ...

.

One major issue with the process that scientists faced was the inefficiency of growing the mould on the surface of their nutrient baths, rather than having it submerged. Even though a submerged process of growing the mould would be more efficient, the strain used was not suitable for the conditions it would require. This led NRRL to a search for a strain that had already been adapted to work, and one was found in a mouldy cantaloupe

The cantaloupe, rockmelon (Australia and New Zealand, although cantaloupe is used in some states of Australia), sweet melon, or spanspek (Southern Africa) is a melon that is a variety of the muskmelon species (''Cucumis melo'') from the fami ...

acquired from a Peoria farmers' market

A farmers' market (or farmers market according to the AP stylebook, also farmer's market in the Cambridge Dictionary) is a physical retail marketplace intended to sell foods directly by farmers to consumers. Farmers' markets may be indoors or o ...

. To improve upon that strain, researchers subjected it to X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s to facilitate mutations in its genome and managed to increase production capabilities even more.

Now that scientists had a mould that grew well submerged and produced an acceptable amount of penicillin, the next challenge was to provide the required air to the mould for it to grow. This was solved using an aerator, but aeration caused severe foaming as a result of the corn steep. The foaming problem was solved by the introduction of an anti-foaming agent known as glyceryl monoricinoleate.

Chemical analysis

Thechemical structure

A chemical structure determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target molecule or other solid. Molecular geometry refers to the spatial arrangement of ...

of penicillin was first proposed by Edward Abraham in 1942. Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin (née Crowfoot; 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994) was a Nobel Prize-winning British chemist who advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of biomolecules, which became essential fo ...

determined the correct chemical structure of penicillin using X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

at Oxford in 1945. In 1945, the US Committee on Medical Research and the British Medical Research Council jointly published in ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

'' a chemical analyses done at different universities, pharmaceutical companies and government research departments. The report announced the existence of different forms of penicillin compounds which all shared the same structural component called β-lactam. The penicillins were given various names such as using Roman numerals in UK (such as penicillin I, II, III) in order their discoveries and letters (such as F, G, K, and X) referring to their origins or sources, as below:

The chemical names were based on the side chain

In organic chemistry and biochemistry, a side chain is a chemical group that is attached to a core part of the molecule called the "main chain" or backbone. The side chain is a hydrocarbon branching element of a molecule that is attached to a ...

s of the compounds. To avoid the controversial names, Chain introduced in 1948 the chemical names as standard nomenclature, remarking as: "To make the nomenclature as far as possible unambiguous it was decided to replace the system of numbers or letters by prefixes indicating the chemical nature of the side chain R."

In Kundl

Kundl is a market town in the Kufstein district in the Austrian state of Tyrol.

Geography

Kundl is situated 7.70 km west of Wörgl as well as 18.30 km southwest of Kufstein at the southern side of the Inn River and is made up of 4 parts ...

, Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, in 1952, Hans Margreiter and Ernst Brandl of Biochemie (now Sandoz

Novartis AG is a Swiss-American multinational pharmaceutical corporation based in Basel, Switzerland and

Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States (global research).name="novartis.com">https://www.novartis.com/research-development/research-loca ...

) developed the first acid-stable penicillin for oral administration, penicillin V

Phenoxymethylpenicillin, also known as penicillin V (PcV) and penicillin VK, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. Specifically it is used for the treatment of strep throat, otitis media, and cellulitis. ...

. American chemist John C. Sheehan at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

(MIT) completed the first chemical synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

* Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

**Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

of penicillin in 1957. Sheehan had started his studies into penicillin synthesis in 1948, and during these investigations developed new methods for the synthesis of peptides

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

, as well as new protecting group

A protecting group or protective group is introduced into a molecule by chemical modification of a functional group to obtain chemoselectivity in a subsequent chemical reaction. It plays an important role in multistep organic synthesis.

In man ...

s—groups that mask the reactivity of certain functional groups. Although the initial synthesis developed by Sheehan was not appropriate for mass production of penicillins, one of the intermediate compounds in Sheehan's synthesis was 6-aminopenicillanic acid

6-APA ((+)-6-aminopenicillanic acid) is a chemical compound used as an intermediate in the synthesis of β-lactam antibiotics. The major commercial source of 6-APA is still natural penicillin G: the semi-synthetic penicillins derived from 6-APA ...

(6-APA), the nucleus of penicillin.

An important development was the discovery of 6-APA itself. In 1957, researchers at the Beecham Research Laboratories (now the Beechem Group) in Surrey isolated 6-APA from the culture media of ''P. chrysogenum''. 6-APA was found to constitute the core 'nucleus' of penicillin (in fact, all β-lactam antibiotics) and was easily chemically modified by attaching side chains through chemical reactions. The discovery was published ''Nature'' in 1959). This paved the way for new and improved drugs as all semi-synthetic penicillins are produced from chemical manipulation of 6-APA.

The second-generation semi-synthetic β-lactam antibiotic methicillin

Methicillin ( USAN), also known as meticillin ( INN), is a narrow-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the penicillin class.

Methicillin was discovered in 1960.

Medical uses

Compared to other penicillins that face antimicrobial resistance ...

, designed to counter first-generation-resistant penicillinases, was introduced in the United Kingdom in 1959. Methicillin-resistant forms of ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posit ...

'' likely already existed at the time.

Outcomes

Fleming, Florey and Chain equally shared the 1945Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

"for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases."

Methods for production and isolation of penicillin were patented by Andrew Jackson Moyer

Andrew J. Moyer (November 30, 1899 – February 17, 1959) was an American microbiologist. He was a researcher at the USDA Northern Regional Research Laboratory in Peoria, Illinois. His group was responsible for the development of techniques for th ...

in the US in 1945. Chain had wanted to file a patent, Florey and his teammates objected to it arguing that it should be a benefit for all. Sir Henry Dale specifically advised that doing so would be unethical. When Fleming learned of the American patents on penicillin production, he was infuriated and commented:

I found penicillin and have given it free for the benefit of humanity. Why should it become a profit-making monopoly of manufacturers in another country?Dorothy Hodgkin received the 1964

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

"for her determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances."

Development of penicillin-derivatives

The narrow range of treatable diseases or "spectrum of activity" of the penicillins, along with the poor activity of the orally active phenoxymethylpenicillin, led to the search for derivatives of penicillin that could treat a wider range of infections. The isolation of 6-APA, the nucleus of penicillin, allowed for the preparation of semisynthetic penicillins, with various improvements overbenzylpenicillin

Benzylpenicillin, also known as penicillin G (PenG) or BENPEN, and in military slang "Peanut Butter Shot" is an antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections. This includes pneumonia, strep throat, syphilis, necrotizing enterocolitis ...

(bioavailability, spectrum, stability, tolerance). The first major development was ampicillin

Ampicillin is an antibiotic used to prevent and treat a number of bacterial infections, such as respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, meningitis, salmonellosis, and endocarditis. It may also be used to prevent group B str ...

in 1961. It was produced by Beecham Research Laboratories in London. It was more advantageous than the original penicillin as it offered a broader spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Further development yielded β-lactamase-resistant penicillins, including flucloxacillin

Flucloxacillin, also known as floxacillin, is an antibiotic used to treat skin infections, external ear infections, infections of leg ulcers, diabetic foot infections, and infection of bone. It may be used together with other medications to t ...

, dicloxacillin

Dicloxacillin is a narrow-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the penicillin class. It is used to treat infections caused by susceptible (non-resistant) Gram-positive bacteria.Product Information: DICLOXACILLIN SODIUM-dicloxacillin sodium capsule. T ...

, and methicillin

Methicillin ( USAN), also known as meticillin ( INN), is a narrow-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the penicillin class.

Methicillin was discovered in 1960.

Medical uses

Compared to other penicillins that face antimicrobial resistance ...

. These were significant for their activity against β-lactamase-producing bacterial species, but were ineffective against the methicillin-resistant ''Staphylococcus aureus'' (MRSA) strains that subsequently emerged.

Another development of the line of true penicillins was the antipseudomonal penicillins, such as carbenicillin

Carbenicillin is a bactericidal antibiotic belonging to the carboxypenicillin subgroup of the penicillins. It was discovered by scientists at Beecham and marketed as Pyopen. It has Gram-negative coverage which includes ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' ...

, ticarcillin

Ticarcillin is a carboxypenicillin. It can be sold and used in combination with clavulanate as ticarcillin/clavulanic acid. Because it is a penicillin, it also falls within the larger class of beta-lactam antibiotics. Its main clinical use is as a ...

, and piperacillin

Piperacillin is a broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the ureidopenicillin class. The chemical structure of piperacillin and other ureidopenicillins incorporates a polar side chain that enhances penetration into Gram-negative bacteria and redu ...

, useful for their activity against Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wa ...

bacteria. However, the usefulness of the β-lactam ring was such that related antibiotics, including the mecillinam

Mecillinam (INN) or amdinocillin (USAN) is an extended-spectrum penicillin antibiotic of the amidinopenicillin class that binds specifically to penicillin binding protein 2 (PBP2), and is only considered to be active against Gram-negative bacteria ...

s, the carbapenem

Carbapenems are a class of very effective antibiotic agents most commonly used for the treatment of severe bacterial infections. This class of antibiotics is usually reserved for known or suspected multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections. S ...

s and, most important, the cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics ...

s, still retain it at the center of their structures.

The penicillins related β-lactams have become the most widely used antibiotics in the world. Amoxicillin, a semisynthetic penicillin developed by Beecham Research Laboratories in 1970, is the most commonly used of all.

Drug resistance

Fleming warned the possibility of penicillin resistance in clinical conditions in his Nobel Lecture, and said:The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.In 1940, Ernst Chain and Edward Abraham reported the first indication of

antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

to penicillin, an '' E. coli'' strain that produced the penicillinase enzyme, which was capable of breaking down penicillin and completely negating its antibacterial effect. Chain and Abraham worked out the chemical nature of penicillinase which they reported in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' as:

The conclusion that the active substance is an enzyme is drawn from the fact that it is destroyed by heating at 90° for 5 minutes and by incubation withIn 1942, strains of ''Staphylococcus aureus'' had been documented to have developed a strong resistance to penicillin. Most of the strains were resistant to penicillin by the 1960s. In 1967, ''papain Papain, also known as papaya proteinase I, is a cysteine protease () enzyme present in papaya (''Carica papaya'') and mountain papaya (''Vasconcellea cundinamarcensis''). It is the namesake member of the papain-like protease family. It has wide ...activated with potassium cyanide at pH 6, and that it is non-dialysable through 'Cellophane Cellophane is a thin, transparent sheet made of regenerated cellulose. Its low permeability to air, oils, greases, bacteria, and liquid water makes it useful for food packaging. Cellophane is highly permeable to water vapour, but may be coated ...' membranes.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

''Streptococcus pneumoniae'', or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, alpha-hemolytic (under aerobic conditions) or beta-hemolytic (under anaerobic conditions), aerotolerant anaerobic member of the genus Streptococcus. They ar ...

'' was also reported to be penicillin resistant. Many strains of bacteria have eventually developed a resistance to penicillin.

Notes

References

Further reading

* * (St Mary's Trust Archivist and Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum Curator)External links

* {{citation , url=http://www.molbio.princeton.edu/courses/mb427/2001/projects/02/antibiotics.htm , title=History of Antibiotics, archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020514111940/http://www.molbio.princeton.edu/courses/mb427/2001/projects/02/antibiotics.htm, archive-date=14 May 2002, access-date=6 August 2013, from a course offered atPrinceton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

Debate in the House of Commons

on the history and the future of the discovery.

Penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from '' Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum usin ...

Penicillins

Microbiology

History of medicine