History of monarchy in Australia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Australia is a

The colony of

Prince Alfred, fourth child of

Prince Alfred, fourth child of

In 1901 Prince George (then the

In 1901 Prince George (then the

During the

During the

An important change in the relationship between the Sovereign and the Australian government and the Governor-General of Australia was marked by the appointment of Sir

An important change in the relationship between the Sovereign and the Australian government and the Governor-General of Australia was marked by the appointment of Sir

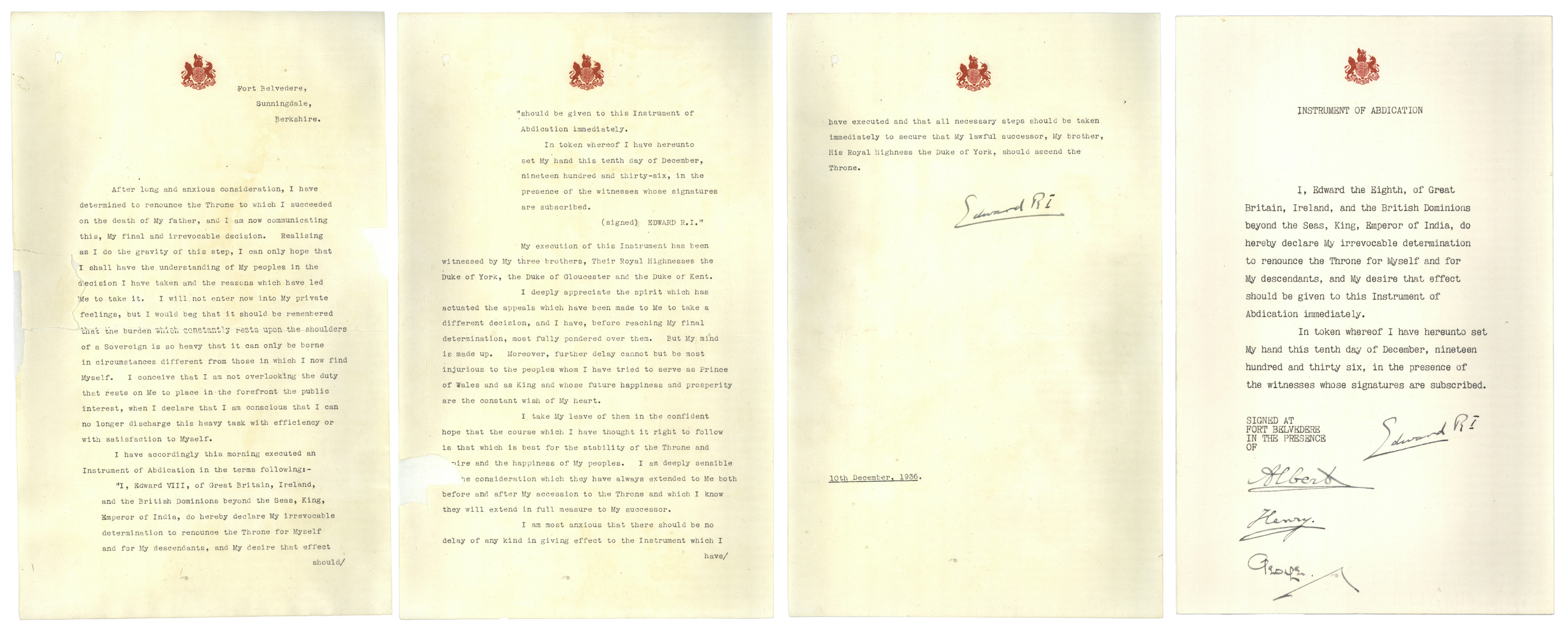

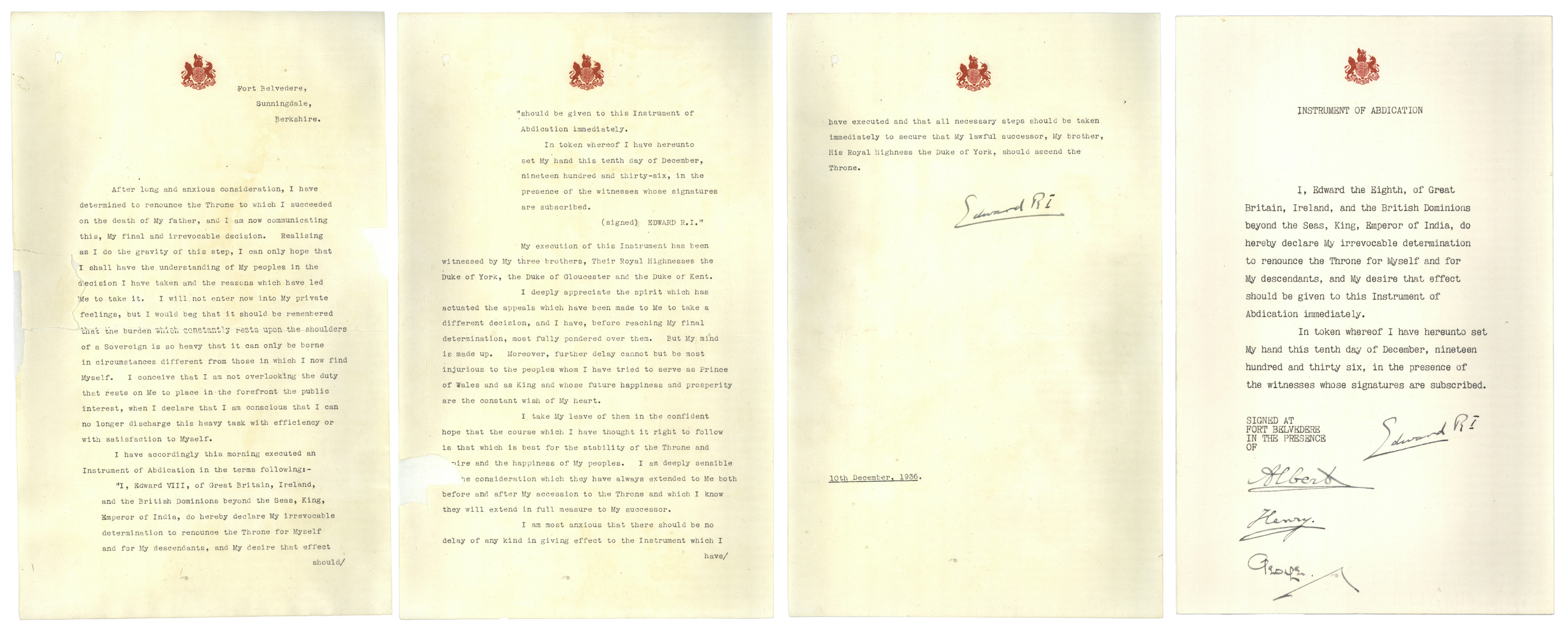

On 10 December 1936

On 10 December 1936

/ref> The United Kingdom government later advised the Queen not to dismiss him, on the grounds that it would be hard to justify the dismissal of Hannah for political involvement, when Kerr remained beyond reproach for his role in the 1975 constitutional crisis. She did, however, refuse to extend his term. The Premier of Queensland,

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

whose Sovereign also serves as Monarch of the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada and eleven other former dependencies of the United Kingdom including Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, which was formerly a dependency of Australia. These countries operate as independent nations, and are known as Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

s. The history of the Australian monarchy

The monarchy of Australia is Australia's form of government embodied by the Australian sovereign and head of state. The Australian monarchy is a constitutional monarchy, modelled on the Westminster system of Parliamentary system, parliamentary ...

has involved a shifting relationship with both the monarch and also the British government.

The east coast of Australia was claimed in 1770, by Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

, in the name of and under instruction from King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

.Queen and Commonwealth: Australia: HistoryThe colony of

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

was founded in the name of the British sovereign eighteen years later, followed by five more: Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

(1825), Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

(1829), South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

(1836), Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

(1851), and Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

(1859).

Royal visits before Federation 1901

Prince Alfred, fourth child of

Prince Alfred, fourth child of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

, became the first member of the Royal Family to visit the burgeoning colonies of Australia. He visited for five months in 1867, when he commanded HMS . He toured Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

. The Melbourne ''Argus'' wrote on 26 November 1867: ' he Colony ofVictoria has not known in her thirty years' life a brighter day than yesterday. A Royal Prince, son of the greatest and noblest Queen that ever sat on the Throne of the British Empire, has landed on our shores, enjoyed our hospitality, and we are proud to know that we have done him honour worthy of ourselves and of the family he represents.'

On his second visit to Sydney, the only assassination attempt against a member of the Royal Family in Australia took place. While the Prince picnicked at Clontarf, near Sydney, Henry James O'Farrell

Henry James O'Farrell (183321 April 1868) was the first person to attempt a political assassination in Australia. On 12 March 1868, he shot and wounded Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria.

Biog ...

, a man of Irish descent, approached Alfred and shot at him, lodging a bullet in his spine. The attack caused indignation and embarrassment in the colony, leading to a wave of anti-Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

sentiment. The next day, 20,000 people attended a meeting to protest at "yesterday's outrage"; Australians felt discomfited by the negative attention being drawn to their colonies.

After the Prince spent five weeks in hospital, the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament Hous ...

voted to approve the erection of a monument to the event, "in testimony of the heartfelt gratitude of the community at the recovery of HRH", which became the Prince Alfred Hospital

The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (abbreviated RPAH or RPA) is a major public teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, located on Missenden Road in Camperdown, New South Wales, Camperdown. It is a teaching hospital of the Central Clinical School of ...

. The Prince granted the use of his coat of arms as the hospital's crest, and the institution later received ''royal'' designation from King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

in 1902.

Fourteen years after the arrival of Prince Alfred, his nephews Princes George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

and Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert ...

arrived to tour South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales, while midshipmen on HMS ''Bacchante''.

Federation

On 1 January 1901 Australia became a nation and dominion of the monarchy. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, public concern over intercolonial tariffs, defence and immigration led to a meeting of colonial representatives in Melbourne in 1889. Dominated by the "Father of Federation", New South Wales Premier SirHenry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. He has ...

, they agreed in principle to a union of the Australian colonies under the British Crown.

A series of constitutional conventions prepared a constitution, which Australians then presented to London. On 1 January 1901, the six Australian colonies federated into one self-governing colony of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

."The Commonwealth shall be taken to be a self-governing colony", Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act This followed the granting of Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the Au ...

by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

on 9 July 1900. Styled a Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

from 1907, Australia was later referred to as a realm

A realm is a community or territory over which a sovereign rules. The term is commonly used to describe a monarchical or dynastic state. A realm may also be a subdivision within an empire, if it has its own monarch, e.g. the German Empire.

Etym ...

of the Crown from the 1950s onward, so as to reflect the equal status of Australia with the other countries under the shared Crown, which came into effect with the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931.

In 1901 Prince George (then the

In 1901 Prince George (then the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

and later King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

) returned to open the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

, in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

.

In 1920 Prince Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

) visited Australia. The public called him the " Digger prince" (''digger'' in Australian slang means an Australian soldier with a particular reputation for bravery and fair play).

In 1927, Prince Albert (later George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

) visited Australia to open the first Parliament to sit in Parliament House

Parliament House may refer to:

Australia

* Parliament House, Canberra, Parliament of Australia

* Parliament House, Adelaide, Parliament of South Australia

* Parliament House, Brisbane, Parliament of Queensland

* Parliament House, Darwin, Parliame ...

, Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

, the Australian capital.

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was the third son and fourth child of King George V and Queen Mary. He served as Governor-General of Australia from 1945 to 1947, the only memb ...

, came to assist in the celebrations of the centenary of the state of Victoria in 1932. In 1945 he was appointed Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of the Commonwealth, against the advice of the Australian government. He was the only member of the Royal Family to serve as a viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

in Australia.

The Statute of Westminster

During the

During the 1926 Imperial Conference

The 1926 Imperial Conference was the fifth Imperial Conference bringing together the prime ministers of the Dominions of the British Empire. It was held in London from 19 October to 22 November 1926. The conference was notable for producing the ...

, the governments of the Dominions and of the United Kingdom endorsed the Balfour Declaration of 1926

The Balfour Declaration of 1926, issued by the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire leaders in London, was named after Arthur Balfour, who was Lord President of the Council. It declared the United Kingdom and the Dominions to be:

The ...

, which declared that the Dominions were autonomous members of the British Empire, equal to each other and to the United Kingdom. The Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that sets the basis for the relationship between the Commonwealth realms and the Crown.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of the ...

gave legal effect to the Balfour Declaration and other decisions made at the Imperial Conferences. Most importantly, it declared that the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

no longer had any legislative authority over the Dominions. Previously, the Dominions were legally self-governing colonies of the United Kingdom, and thus had no legal international status. The Statute made the Dominions ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' independent nations.

The Statute took effect immediately over Canada, South Africa and the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

. However, Australia, New Zealand and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

had to ratify the Statute through legislation before it would apply to them. Canada also requested certain exemptions from the Statute in regard to the Canadian Constitution

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents a ...

.

Australian politicians initially resisted ratification of the Statute. John Latham, the Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs under Prime Minister Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office, 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He ...

, was particularly opposed to ratifying the Statute, because he thought it would weaken military and political ties with the United Kingdom. Latham had attended both the 1926 Imperial Conference and the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, and he had much experience in international affairs. He preferred that the relationship between the United Kingdom and the Dominions not be codified in legislation.

However, other politicians supported the Statute, and the new independence it gave to Australia.

With the passage of the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942

The Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 is an act of the Australian Parliament that formally adopted sections 2–6 of the Statute of Westminster 1931, an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom enabling the total legislative independ ...

, the British Parliament could no longer legislate for the Australian Commonwealth without the express request and consent of the Australian Parliament. The act received Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

on 9 October 1942, but the adoption of the Statute was made retroactive to 3 September 1939, when Australia entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The Isaacs appointment

An important change in the relationship between the Sovereign and the Australian government and the Governor-General of Australia was marked by the appointment of Sir

An important change in the relationship between the Sovereign and the Australian government and the Governor-General of Australia was marked by the appointment of Sir Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

as Governor-General. Isaacs was the first Australian-born Governor-General. The Commonwealth Cabinet, headed by James Scullin

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian Labor Party politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Scullin led Labor to government at the 1929 Australian federal election. He was the first Catho ...

, considered his name in 1930. Isaacs was Chief Justice and a Justice of the High Court.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

had asserted the right of dominion governments to be consulted on the choice of Governors-General in 1919. Prime Minister Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

had made a similar assertion two decades earlier. Hughes was invited to select the name of the Governor-General from a list of three (British) names made up by the Secretary of State of the Colonial Office. The choice was however recommended to the King, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, by the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs.

But the Commonwealth government directly nominating and recommending a Governor-General occasioned a controversy, both in the press at home and in Buckingham Palace. The Leader of the Opposition, John Latham, took the view that the federal executive councillors could advise the Governor-General, but not the King. George V was of the same opinion. The King's private secretary wrote to the secretary of State in London:

His Majesty feels strongly that it would be a grave mistake to give the Prime Minister of the Commonwealth an opportunity of naming the next Governor-Generalquoted in Cunneen, King's Men, p.170; And George, believing that the Governor-General was the personal representative of the Sovereign, intervened directly. The Palace wrote:

The King feels that, with the change in the position of the governor-general (sic) made at the Imperial Conference of 1926, which divested them of all political power and eliminated them from the administrative machinery of the respective Dominions, leaving them merely as the representative of the Sovereign, more than ever His Majesty should be consulted in the selection of candidates, and indeed, subject of course to the concurrence of the British Prime Minister, be left to make the choice himself.Scullin raised the question of dominion governments directly advising the King on vice-regal appointments at the 1930

Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

. It was decided that the King should act on the advice of his dominion ministers. Still, Scullin had to go to London personally to persuade the King to appoint Isaacs. George reluctantly agreed. After Isaacs, two more British nominees followed: Lord Gowrie (1936–1945) and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was the third son and fourth child of King George V and Queen Mary. He served as Governor-General of Australia from 1945 to 1947, the only memb ...

(1945–1947). Nevertheless, the principle had been established that the Governor-General was the constitutional representative, not the personal representative, of the Sovereign. This was an important step in establishing the independence of the office. In 1988, the commission established by the government of Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

to review the Constitution could report:

Although the Governor-General is the Queen's representative in Australia, the Governor-General is in no sense a delegate of the Queen.

Secessionist Movement

The isolated, mineral-rich colony ofWestern Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

had been reluctant to federate. The Constitution does not list Western Australia as one of the original states. Discontent with federation lead to a referendum on 8 April 1933. In answer to the question 'are you in favour of the State of Western Australia withdrawing from the Federal Commonwealth established under the Commonwealth of Australia Constitutional Act (Imperial)?' the people of Western Australia voted in the affirmative by two to one.

The referendum brought the secessionist Labor government of Philip Collier

Philip Collier (21 April 1873 – 18 October 1948) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th Premier of Western Australia from 1924 to 1930 and from 1933 to 1936. He was leader of the Labor Party from 1917 to 1936, and is Western Aus ...

to power. In 1934 the new government sent a delegation to London to petition the King, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, and the British Parliament to overturn the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the Au ...

. Such an act would have dissolved the Commonwealth and left the states free to federate anew or not as they wished. A joint committee of the House of Lords and House of Commons considered the petition, and rejected it in 1935. It did so on the grounds that it could not overturn the Act without the approval of the Federal Parliament.

Abdication of Edward VIII

On 10 December 1936

On 10 December 1936 Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

abdicated after it became clear that the British and Dominion governments would not accept his intended marriage to American divorcee and commoner, Wallis Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986), was an American socialite and wife of the former King Edward VIII. Their intention to marry and her status as a divorcée caused ...

. The Statute of Westminster required the Dominion governments be consulted on matters relating to the succession. The Dominions Office in London proposed three solutions to the crisis to the governments of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Canada:

*marriage of the King to Simpson; Simpson would become Queen

*a morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spous ...

(Simpson would not have the title or honours of a queen, and any issue would have no rights of succession)

*abdication of the King.

Australia, South Africa and Canada chose abdication. India and New Zealand had no firm view.

According to Harold Laski, writing in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'',

This issue is independent of the personality of the King. It is independent of the personality of the Prime Minister. It does not touch on the wisdom or unwisdom of the marriage the King has proposed. It is not concerned with the pressure, whether of the churches or the aristocracy, that is hostile to this marriage. It is the principle that out of this issue no precedent must be created that makes the Royal authority once more a source of independent political power in the State.According to this view, the constitutional independence of the Dominions was at stake. This event demonstrated the legal independence of the Dominion monarchies established by the Statute of Westminster.

Reign of Elizabeth II

In 1954, QueenElizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

became the first reigning Australian monarch to visit Australia. Her presence provided a sense of certainty to the nation, as well as focusing world attention on Australia. Around 7 million Australians (of a total population of just under 9 million at the time) greeted her.

She has since returned on several occasions (a total of 15 official visits) and has officiated at such important moments as the bicentenary __NOTOC__

A bicentennial or bicentenary is the two-hundredth anniversary of a part, or the celebrations thereof. It may refer to:

Europe

*French Revolution bicentennial, commemorating the 200th anniversary of 14 July 1789 uprising, celebrated i ...

in 1970 of James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

's voyage along the East Coast of Australia; the opening of the Sydney Opera House

The Sydney Opera House is a multi-venue performing arts centre in Sydney. Located on the foreshore of Sydney Harbour, it is widely regarded as one of the world's most famous and distinctive buildings and a masterpiece of 20th-century architec ...

in 1973; her Silver Jubilee in 1977; proclamation of the Australia Act

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by a ...

in 1986; various events commemorating the bicentenary __NOTOC__

A bicentennial or bicentenary is the two-hundredth anniversary of a part, or the celebrations thereof. It may refer to:

Europe

*French Revolution bicentennial, commemorating the 200th anniversary of 14 July 1789 uprising, celebrated i ...

of the arrival of First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

and the opening of the new Parliament House

Parliament House may refer to:

Australia

* Parliament House, Canberra, Parliament of Australia

* Parliament House, Adelaide, Parliament of South Australia

* Parliament House, Brisbane, Parliament of Queensland

* Parliament House, Darwin, Parliame ...

in Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

in 1988; the centenary of federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

in 2000; her Golden Jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali ''"সু ...

in 2002; and more.

The National Carillon

The National Carillon is a large carillon situated on Queen Elizabeth II Island in Lake Burley Griffin, central Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, Australia. The carillon is managed and maintained by the National Capital Authority o ...

in Canberra was dedicated by Elizabeth II on 25 April 1970. The Swan Bells in Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

include the twelve bells of Saint Martin-in-the-Fields that were cast between 1725 and 1770 by three generations of the Rudhall family of bell founders from Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

, under the order of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, later crowned as King George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

. Donated to Perth in 1988, they are known to have pealed as the explorer James Cook set sail on the voyage that founded Australia, and are the only sets of royal bells to have left England.

Queen of Australia

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

is the first monarch to be styled sovereign of Australia. In 1953 the Australian Parliament passed two bills. The first was the ''Royal Style and Titles Act 1953''. This added the word "Australia" to the Queen's titles. In 1973 a further Act removed "Defender of the Faith

Defender of the Faith ( la, Fidei Defensor or, specifically feminine, '; french: Défenseur de la Foi) is a phrase that has been used as part of the full style of many English, Scottish, and later British monarchs since the early 16th century. It ...

" from her Australian title. In 1958 Elizabeth amended the letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

which constituted the office of Governor-General.

Until then Australian constitutional documents were signed by the monarch and counter-signed by a British minister of state. But now such documents were to be counter-signed by the Prime Minister of Australia. Further, they were to be sealed with the Royal Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Australia. Queen Victoria's letters patent had ordered a Great Seal for Australia in 1900, but it was never made. On 19 October 1955 Elizabeth, advised by Prime Minister Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, issued a warrant for the Seal.

The ''Royal Powers Act 1953'' further secured the Sovereign's new status as Queen of Australia by conferring on her powers that the Constitution did not give her. The Queen could now preside at Federal Executive Councils in person and open the Commonwealth Parliament. Elizabeth II has performed both actions three times each.

On 30 May 1973 the prerogative of appointing Australian ambassadors to nations outside the Commonwealth was transferred to the Governor-General. Likewise the viceroy assumed authority to appoint high commissioners to Commonwealth countries. The line of communication between Sovereign and viceroy became the Australian High Commission in London, in place of the British High Commission

A British High Commission is a British diplomatic mission, equivalent to an embassy, found in countries that are members of the Commonwealth of Nations. Their general purpose is to provide diplomatic relationships as well as travel information, ...

in Canberra. When mention of the United Kingdom was removed from the Queen's titles in Australia in the same year, the government of the state of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, concerned that this action was a first step towards declaring Australia to be a republic, sought to declare her "Queen of Australia, Queensland and her Other Realms and Territories", in order to ensure that the Monarchy would at least be entrenched in Queensland.

The action was blocked by the High Court of Australia in the so-called ''Queen of Queensland'' case in 1974. However, it highlighted the fact that the relation of the Australian states to the Crown was then independent of the relation of the Commonwealth to the Crown, and this paradox led to the Hannah and the Wran affairs which eventually led to the Australia Act

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by a ...

of 1986.

The Dismissal, and the Hannah and Wran Affairs

The Australian monarch rarely intervenes in Australian affairs. During the 1975 constitutional crisis over the failure of Gough Whitlam's Labor government to secure supply, the Queen remained neutral, which both sides of the debate took to imply tacit approval. When Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Whitlam, the Labor Speaker of the House of Representatives,Gordon Scholes

Gordon Glen Denton Scholes AO (7 June 1931 – 9 December 2018) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and served in the House of Representatives from 1967 to 1993, representing the Division of Corio ...

, asked the Queen to revoke her viceroy's act. The Queen's Private Secretary replied:

As we understand the situation here, the Australian Constitution firmly places the prerogative powers of the Crown in the hands of the Governor-General as the representative of the Queen of Australia. The only person competent to commission an Australian Prime Minister is the Governor-General, and The Queen has no part in the decisions which the Governor-General must take in accordance with the Constitution. Her Majesty, as Queen of Australia, is watching events in Canberra with close interest and attention, but it would not be proper for her to intervene in person in matters which are so clearly placed within the jurisdiction of the Governor-General by the Constitution Act.The reluctance of the Queen of Australia to become involved in this high-profile political crisis involving the Commonwealth government contrasted with other instances when the monarch and her officers became directly involved in the politics of Australian states. In 1975, prior to the Dismissal, the

Governor of Queensland

The governor of Queensland is the representative in the state of Queensland of the monarch of Australia. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governor Governors of the Australian states, performs c ...

, Sir Colin Hannah

Air Marshal Sir Colin Thomas Hannah, (22 December 1914 – 22 May 1978) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and a Governor of Queensland. Born in Western Australia, he was a member of the Militia before joining the ...

criticised the Whitlam government in a partisan manner. At the time, Hannah was commissioned Administrator

Administrator or admin may refer to:

Job roles Computing and internet

* Database administrator, a person who is responsible for the environmental aspects of a database

* Forum administrator, one who oversees discussions on an Internet forum

* N ...

, or acting governor-general, whenever John Kerr was out of the country. The Queen acted on Whitlam's advice to withdraw this commission.''The hidden hand of Her Majesty''/ref> The United Kingdom government later advised the Queen not to dismiss him, on the grounds that it would be hard to justify the dismissal of Hannah for political involvement, when Kerr remained beyond reproach for his role in the 1975 constitutional crisis. She did, however, refuse to extend his term. The Premier of Queensland,

Joh Bjelke-Petersen

Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (13 January 191123 April 2005), known as Joh Bjelke-Petersen, was a conservative Australian politician. He was the longest-serving and longest-lived premier of Queensland, holding office from 1968 to 1987, during ...

argued that the Queen is to be advised by the state premier on her choice of governors, and so London ought not to advise the sovereign in the matter. Whitlam's successor, Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

, sought to have Hannah's commission restored. He was refused, and the British foreign secretary, Lord Carrington

Peter Alexander Rupert Carington, 6th Baron Carrington, Baron Carington of Upton, (6 June 1919 – 9July 2018), was a British Conservative Party politician and hereditary peer who served as Defence Secretary from 1970 to 1974, Foreign Secret ...

, then the principal adviser to the Queen on state matters, advised Hannah of his impropriety during Whitlam's term of office.

This episode greatly concerned the Australian state premiers on both sides of politics. They had governed in the belief that convention meant they were the Queen's advisers in state matters, not British ministers. London's actions were indicative of the direct relationship between the Queen of the United Kingdom and the Governors of the Australian states. This relationship now appeared to bypass the Queen's role as the Australian monarch, and her link to the Governor-General and the Commonwealth. Apparently the Queen of the United Kingdom still had direct powers over the Australian states where she acted in that role on the advice of her British ministers.

State governors had been dismissed by monarchs before. In 1917 George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

had recalled Sir Gerald Strickland

Gerald Paul Joseph Cajetan Carmel Antony Martin Strickland, 6th Count della Catena, 1st Baron Strickland, (24 May 1861 – 22 August 1940) was a Maltese and British politician and peer, who served as Prime Minister of Malta, Governor of the L ...

, Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the ...

. Strickland had leaked to the press that he was about to dismiss the premier, William Holman

William Arthur Holman (4 August 1871 – 5 June 1934) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of New South Wales from 1913 to 1920. He came to office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (New South Wales Branch), Labor Party, ...

. However, the King had been acting at the request of Holman, and the King had acted according to convention, on the advice of his chief minister.

In 1980 Neville Wran

Neville Kenneth Wran, (11 October 1926 – 20 April 2014) was an Australian politician who was the Premier of New South Wales from 1976 to 1986. He was the national president of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1980 to 1986 and chairman of ...

, the Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislature. ...

, announced his intention to introduce a bill that would require the Queen to be advised by Australian state ministers alone on matters concerning the governance of that state.

Wran had tested the British ministers by requesting the Governor of New South Wales not be told of his impending re-appointment. When British officials ignored this request, Wran took it as proof of their willingness to interfere in Australian state affairs. Buckingham Palace was alarmed at the impending bill, and when it was passed through both houses of the New South Wales Parliament, Lord Carrington wrote to Sir Roden Cutler

Sir Arthur Roden Cutler, (24 May 1916 – 21 February 2002) was an Australian diplomat, the longest serving Governor of New South Wales and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry "in the face of the enemy" that ca ...

, the state's Governor, telling him that the Queen would refuse the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

to the bill.'I recalled to her majesty(sic) that it was my duty to advise her to refuse her assent to legislation which in my own view was unconstitutional whatever my view of the merits of such legislation might be.' The secretary of the Premier's Department, Gerry Gleason, told the British Consul-General that New South Wales was 'being buggered about' and that the British needed their 'backsides kicked'.

The constitutional problem was resolved by the Australia Act 1986

The Australia Act 1986 is the short title of each of a pair of separate but related pieces of legislation: one an Act of Parliament, Act of the Commonwealth (i.e. federal) Parliament of Australia, the other an Act of Parliament (UK), Act of ...

. By this Act all state governors are appointed by the Queen on the advice of the Australian state's Premier alone. British ministers have no constitutional authority to advise the Queen on any matter related to the Australian states. There is debate as to whether the actions of the Australian states have in effect made Queen Elizabeth their direct monarch the same way she is Queen of Australia, effectively making her the Queen of New South Wales, of Victoria, of Tasmania, of South Australia, of Western Australia, and also the Queen of Queensland.

Referendum on the monarchy

In the 1970s more Australians began to seriously reconsider Australia's constitutional framework. The constitutional crisis of 1975 occasioned many to question the role of the monarchy in a modern Australia. There were no serious attempts to alter the constitutional role of the Queen until the 1986 Australia Act. Nevertheless Australians were more conscious of being an independent nation, and there was a downplaying of the monarchy in Australia, with references to the monarchy being removed from the public eye (e.g., the Queen's portrait from public buildings and schools). Public attitudes were quietly changing, though republicanism did not become a seriously considered proposition until 1991, whenLabor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

Prime Minister Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). He previously serv ...

formed the Republic Advisory Committee

The Republic Advisory Committee was a committee established by the then Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating in April 1993 to examine the constitutional and legal issues that would arise were Australia to become a republic. The committee's man ...

to investigate the possibility of Australia becoming a republic. Under Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

/National

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

Coalition Prime Minister John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the s ...

, Australia held a two-question referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

. The first question asked whether Australia should become a republic with a president appointed by parliament, a bi-partisan appointment model which had previously been decided at a constitutional convention in February 1998.

The second question, generally deemed to be far less important politically, asked whether Australia should alter the constitution to insert a preamble. Neither of the amendments passed, with the question on the republic defeated by 54.4% in the popular vote and 6-0 in the states. While monarchists declared the result proof that the people were happy with the monarchy, republican voices stated that it was indicative of the lack of choice given in the republican model.

Four months after the referendum, the Queen returned to Australia in 2000. In Sydney, in a speech at the Conference Centre in Darling Harbour, she stated her belief in the democratic rights of Australians on all issues including that of the monarchy:

My family and I would, of course, have retained our deep affection for Australia and Australians everywhere, whatever the outcome. For some while it has been clear that many Australians have wanted constitutional change... You can understand, therefore, that it was with the closest interest that I followed the debate leading up to the referendum held last year on the proposal to amend the Constitution. I have always made it clear that the future of the monarchy in Australia is an issue for you, the Australian people, and you alone to decide by democratic and constitutional means. It should not be otherwise. As I said at the time, I respect and accept the outcome of the referendum. In the light of the result last November I shall continue faithfully to serve as Queen of Australia under the constitution to the very best of my ability, as I have tried to do for the last 48 years.

The new millennium

In March 2006, organisers of the2006 Commonwealth Games

The 2006 Commonwealth Games, officially the XVIII Commonwealth Games and commonly known as Melbourne 2006 (Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm 2006'' or ''Naarm 2006''), was an international multi-sport event for members of the Commonwealth held ...

in Melbourne came under fire when it was announced that they would not play "God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" is the national and/or royal anthem of the United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth realms, their territories, and the British Crown Dependencies. The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in plainchant, bu ...

" at the ceremonies where the Queen was to open the Games. Despite the fact that the song is officially the Australian Royal Anthem, to be played whenever the sovereign is present, the games organisers refused to play it. After repeated calls from Prime Minister John Howard, organisers agreed to play eight bars of the Royal Anthem at the opening ceremony.

However, there remained speculation that the opening of the games could be "thrown into chaos" should thousands of Australians continue to sing "God Save the Queen" after the eight bars were complete, drowning out singer Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

Dame Kiri Jeanette Claire Te Kanawa , (; born Claire Mary Teresa Rawstron, 6 March 1944) is a retired New Zealand opera singer. She had a full lyric soprano voice, which has been described as "mellow yet vibrant, warm, ample and unforced". Te ...

and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an Australian orchestra based in Melbourne. The MSO is resident at Hamer Hall. The MSO has its own choir, the MSO Chorus, following integration with the Melbourne Chorale in 2008.

The MSO relies on f ...

. In the end, with the crowd singing along, Dame Kiri sang Happy Birthday to the Queen, the rendition of which then turned into an abbreviated God Save the Queen, and at which point the majority of attendees at the stadium stood.

When Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian former politician and diplomat who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and again from June 2013 to September 2013, holding office as the leader of the ...

assumed office in 2007, he stated that the republic was not a priority for his first term. He did affirm that it formed part of the Labor policy platform. During a visit to Britain in April 2008 he stated his belief that the republican debate should continue. During the weekend of 19/20 April a meeting of various members of Australian society met in Canberra to come up with ideas for Australia's future. This has become known as the Australia 2020 Summit

The Australia 2020 Summit was a convention, referred to in Australian media as a summit, which was held over 18-19 April 2008 at Parliament House in Canberra, Australia, aiming to "help shape a long-term strategy for the nation's future". Announ ...

. The republic was floated again, and widely supported. Rudd came out in support and intimated that the republic may become a reality before the end of the reign of Elizabeth II. Former Prime Minister Julia Gillard

Julia Eileen Gillard (born 29 September 1961) is an Australian former politician who served as the 27th prime minister of Australia from 2010 to 2013, holding office as leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). She is the first and only ...

(2010-2013 ) stated that she is a republican. However she wished an appropriate model of republic be explored before the issue was taken to the people again. Kevin Rudd did not flag the question of a republic during his second term of office as Prime Minister.

Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull (born 24 October 1954) is an Australian former politician and businessman who served as the 29th prime minister of Australia from 2015 to 2018. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Turnbull grad ...

said of Queen Elizabeth's reign: "She's been an extraordinary head of state, and I think, frankly, in Australia, there are more Elizabethans than there are monarchists."

One idea for the future of an Australian monarchy is to establish a uniquely Australian monarch who would reside permanently in Australia. The first known publication of this idea was in 1867. One possibility would be to crown someone who is in line to the Australian throne, but who is not expected to become monarch of the United Kingdom. There are thousands of people in line to the Australian throne. As a compromise solution, this has not been seriously discusses by either Australian monarchists and republicans. Members of the Australian public take a keen interest in this topic.

Monarchs of Australia

The monarchs of Australia are the same as those of the United Kingdom. The sovereigns reigned over Australia as monarchs of the United Kingdom until 1942 (by a legal fiction, from 1939). From that year they reigned as sovereigns in right of Australia, though the first to be accorded an Australian title, Queen of Australia, was Elizabeth II, in 1953. After the Queens death in 2022, her son Charles III took over.Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * {{Australia topics Monarchy in AustraliaMonarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...